Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 24:17 — 28.8MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

You can read, listen, or watch

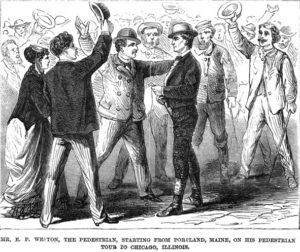

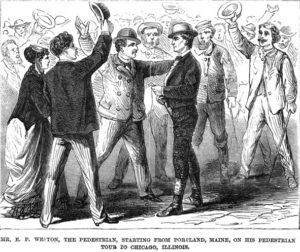

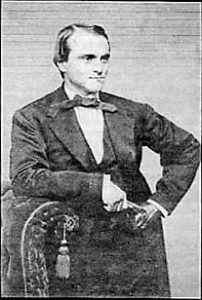

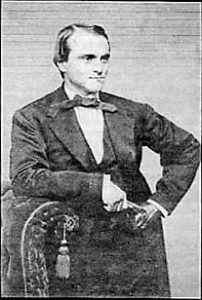

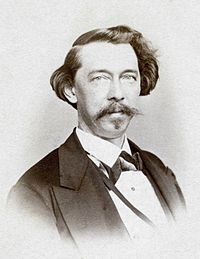

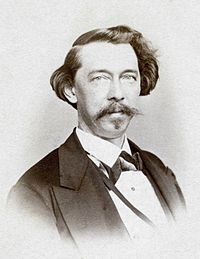

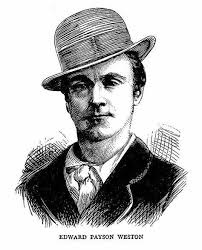

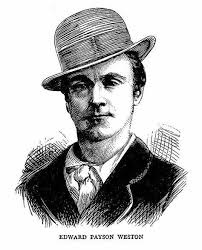

Reaching the 1870s, the six-day challenge had not yet been exported outside Britain. But that changed as the challenge reached America and moved almost exclusively indoors, thanks to Weston. He became the most famous pedestrian in history. Weston was introduced in episode 54 for his impact on 100-mile history and in episode 26 for his famed transcontinental walk. Now we will examine his early impact of importing the six-day event to America, trying to reach 400 and 500 miles.

| Help is needed to continue the Ultrarunning History Podcast and website. Please consider becoming a patron of ultrarunning history. Help to preserve this history by signing up to contribute a few dollars each month through Patreon. Visit https://ultrarunninghistory.com/member |

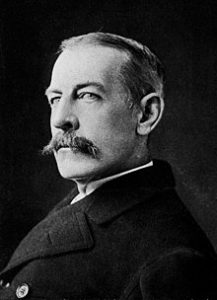

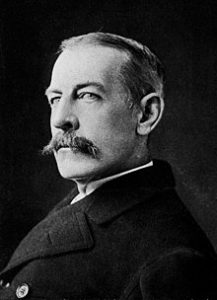

Edward Payson Weston

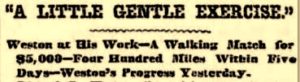

Weston’s Fame Grows

In April 1870, Weston walked 100 miles in 21:38:20 in New York City, an accomplishment that silenced many critics. (For more about his early walking career, see episode 54.)

During 1870, Weston came up with the idea to attempt to walk 400 miles in five days, as pedestrians fifty years earlier were trying to do. Had Weston, in 1870, heard about Foster Powell’s historic runs?

![]()

![]()

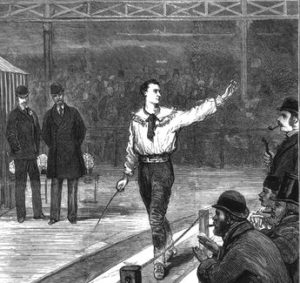

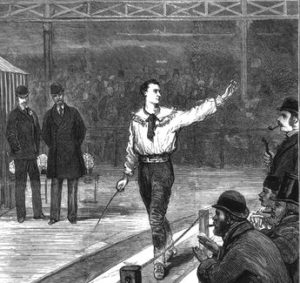

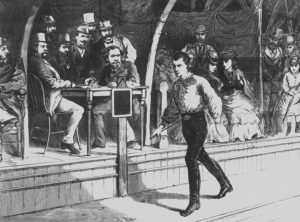

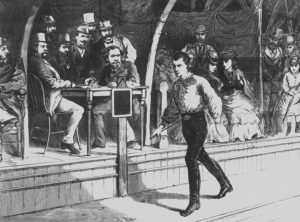

Did Weston truly walk? His distinctive wobbly walking gait was a swinging stride, with a relaxed upper body and shoulders without pumping his arms. The action came mostly from his knees. Starting in the 1840s, a “fair heel-and-toe” racewalking style was established for walking in competitions. Weston was criticized by some of not using a true heel-toe racewalk, that it border-lined on running at times, with both feet off the ground at the same time.

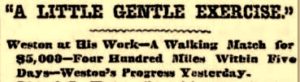

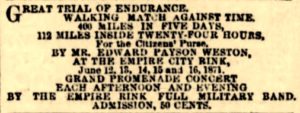

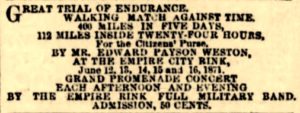

Weston’s First Multi-Day Attempt – 1870

Weston’s $5,000 wager agreement required him to reach 400 miles in five days, and he also needed to walk 112 miles within a 24-hour period and for the other days, must stop to rest for four consecutive hours each day. He went into specific training during the three weeks leading up to the event. It was billed as being a scientific experiment sponsored by a committee of medical men “for the advancement of science by investigation as to his physical condition, weight, of his food, the quantity of excretions, the conditions of the heart, temperature, etc. for five days previous, five days during and five days after.” Professor Charles Avery Doremus (1851-1925), a chemist of Bellevue Hospital Medical College in New York City, headed up the team to help Weston and study the walk. Doremus studied and lectured on the effects of chemicals on the body.

Skeptics were vocal. One wrote in the Spirit of the Times, “Is there in all this city a man so credulous and unwary as to believe that these six ‘most eminent men’ got together of their own motion and addressed a long letter to this fellow Weston for the advancement of science? If these is, there is a bigger fool in this community than we had thought it possessed.”

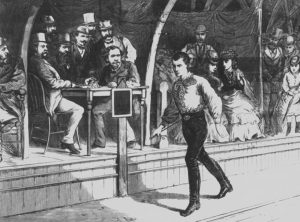

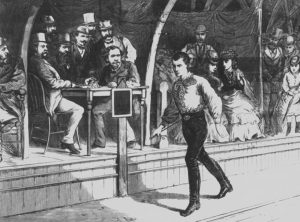

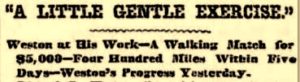

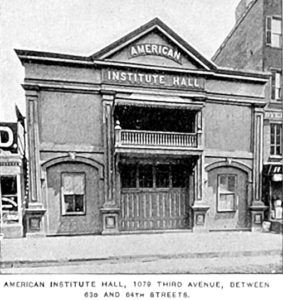

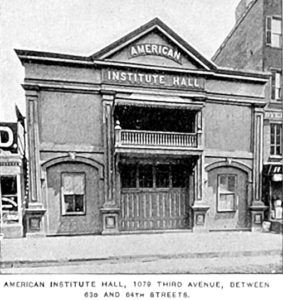

Empire Skating Rink

The event was held in the Empire Skating Rink in New York City on 63rd Street and Third Avenue. This was a massive ice-skating rink, under an arched cast iron structure, 350 feet long, 170 feet wide, and 70 feet high. The arch was enclosed within a large building. The structure included a raised platform for spectators and could seat 10,000 people. At its grand opening a few years before, 3,000 skaters visited the rink. This venue was the site of Weston’s earlier 100-mile walk.

For Weston’s 400-mile try, newspapers promised a “grand promenade concert” each afternoon and evening put on by the “Empire Rink Full Military Band.” Admission was 50 cents. The walking track laid down on the surface was measured out at being a little less than seven laps to the mile.

The Start

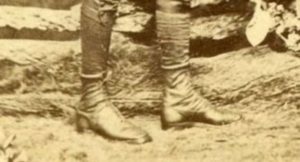

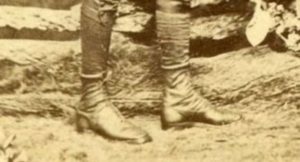

On the evening before the big event, Weston took a supper of beefsteak, fried eggs, toast and stew. His walk began on November 21, 1870, at 12:30 a.m., weighing in for the doctors at 129 pounds. He entered the scene accompanied by Ole Bull (1810-1880), a famous Norwegian violinist. Weston was dressed in his usual “costume of black velvet, white silk hat, blue sash, white kid gloves, top boots reaching to the knees on the outside of the pantaloons, and gold-mounted riding-whip.” Six judges took their seats with pencils and a watch. The word “go” was given and he started off, covering the first mile in 13:08.

The Brooklyn Newspaper joked about all the doctors watching and poking him. “Weston’s case will command much sympathy. It is bad enough to get in the hands of one doctor, but the victim of half a dozen is indeed a deplorable plight.” They also joked that Ole Bull should be required to play his violin for five consecutive days too. “This would afford a test of musical as well as physical endurance and would also draw a crowd.”

Spectators Thrilled

After reaching 20 miles, Weston went to bed. His distance to and from his bed was counted into his total distance. Rising before 8 a.m., he ate a breakfast that perhaps modern six-day runners should give a try: mutton-chops, egg flip (similar to eggnog), stale bread, and eight ounces of coffee.

After reaching 50 miles, the band took their stand in the center of the hall and began playing a series of lively marches which perked up Weston. “Whem he started again, he was full of fun, marching slowly in time to the music, walking backward and changing hats with one of the doctors, to the great amusement of the crowd.”

In the evening the hall was filled with spectators again who watched at the apparently fascinating sight of Weston walking as he swung his arms loosely by his side. At the end of the first day, he was right on schedule and reached 80 miles.

Attempt to walk 112 miles in 24 hours

He and his handlers eventually realized that it wouldn’t be possible to complete the 112-mile challenge, and at his 266th mile, while very dizzy, he gave up that quest and went off to bed. To reach 400 miles in five days, he needed 126 more miles on day five.

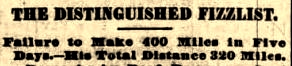

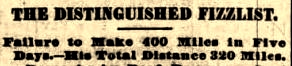

Failure to Reach 400 Miles

Weston sprinted his fastest laps during his last mile which delighted the crowd. He finished during the evening of the fifth day with 320 miles, with no plans to continue on and try to match Powell’s 400 miles in six days. The doctors announced that during his “tramp” he did not take in any “liquor or other stimulant, or any narcotic,” but was affected negatively by the tobacco smoke that filled the rink.

Professor Doremus proclaimed that “they had witnessed one of the proudest illustrations of physical endurance on record, in sacred or profane history since Adam.” Weston spoke and thanked his friends for their encouragement.

Newspapers across the country published the news of his “failure” and some called it a “foolish attempt.” Other comments were especially cruel, saying that Weston was trying to walk himself to death and that they were sorry he failed doing that too. He was called a “peripatetic humbug.” The New York City press was especially delighted that he “failed lamentably to make the new dodge a success,” charging that the entire event was a money grab attempt on the gullible public and that the “advancement of science” twist was lame. They were sure he would again attempt to “hoodwink the public.”

Near-Death Accident

Weston’s Second Multi-Day Attempt – 1871

The track laid down for him on the rink was again seven laps to a mile, with a two-inch layer of dirt and sawdust on the boards, which was an improvement on the track surface from the previous year. Improvements were also made to the air ventilation in the building.

Weston kept up a good pace during the first day. “His step was quick and buoyant, and his friends seemed confident of his ability to accomplish his giant undertaking.” By noon he reached 62 miles, on target for his 112-mile day. He kept it up until 5 p.m. (17.5 hours) when he stopped for a brief rest and a “hearty meal.” “The Rink was thronged in the evening with spectators eager to witness the great feat of pedestrianism.” He reached 100 miles in an impressive 21:01 and succeeded reaching 112 miles in 23:44:45.

Some in the press did understand what an amazing accomplishment that was. “Weston has almost immortalized himself. He has, in spite of countless assertions as to his inability by Bohemian critics, performed the marvelous feet of walking 112 miles within 24 hours.”

![]()

![]()

He started his final day’s walk at 4:43 a.m. after a good sleep of four hours. He knew he had to walk 80 more miles. After the first 20 miles, in 5:22, on swollen feet, he stopped for 20 minutes for breakfast and a rest. Continuing on, he did not stop until reaching 50 miles in 10:53. For the final 30 miles, he exchanged his velvet suit for silk tights. “During the last five miles, both Weston and the audience were aroused to an intense state of excitement, cheering almost continually, and Weston winning applause by walking backwards, running, jumping, and performing many playful tricks in order to demonstrate the large amount of physical force he yet held in reserve.” During the last lap, with 18 minutes to spare, his face was glowed and he finished his 400 miles in four days, 23 hours, 42 minutes, just twenty minutes slower than the fastest known time accomplished in 1822.

![]()

![]()

Cornelius Payn Tries to Outdo Weston

Walking at Fairs

In South Carolina it was reported, “Edward Payson Weston, the famous pedestrian, offers to walk at agricultural fairs during the ensuing fall for the modest sum of $150.” In September 1873, he was able to book a fair exhibition in West Virginia to walk five miles in an hour. He also was working as a reporter for the New York Sun. With the horse carriage traffic in the city, he was seen beating horses when in a hurry to get a story.

Weston’s reputation seemed to be declining and he needed to do something big in 1874, something that no one had ever accomplished before.

Weston Attempts 500 miles in Six Days – May 1874

Doubters and Supporters

Weston’s true motives for attempting 500 miles were questioned, but one writer actually identified some public value. “The example of Weston will induce our young men to use their legs rather than the street cars, to the great benefit of their health, and the much-needed relief of the public conveyances. By going to see him, citizens would gather useful information concerning the art of walking, in which most of them are as profoundly ignorant as if nature had not gifted them with legs.”

The Start

The track he walked on measured seven laps for a mile, was 40 inches wide and filled with dirt. Weston started at 12:05 a.m., Monday morning on May 11, 1874. In our era of high-tech running clothes, we obviously have an amazed reaction to his typical getup, called a full pedestrian costume. “This consisted of a loose black velvet sack coat, black velvet knee britches, black leggings, high laced walking shoes, a white hat, and a wide, sky-blue silk scarf, and in hand he carried a small riding whip.”

Weston was paced for the first few laps by James Gordon Bennett Jr. (1841-1918), the publisher of the New York Herald. “Much merriment was occasioned by Mr. Bennett’s attempt to keep up with Mr. Weston, and when the journalist made the terrible spurt, swinging his arms wildly and straining every muscle, almost everybody laughed.”

How Weston was Crewed

The enthusiastic spectators were just as important motivators as his handlers were. They spurred him on as the live band livened things up. Weston responded with smiles and bows. During the early morning, he slept in his room for several hours and was usually back on the track by 5 a.m. when spectators started returning. At times Weston, wanting more attention, would pour on the walking speed which caused the ladies to go crazy with excitement as they waved handkerchiefs. One third of the spectators who came each day were ladies.

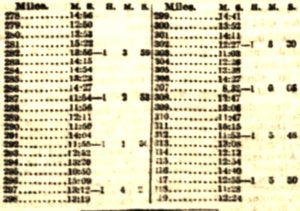

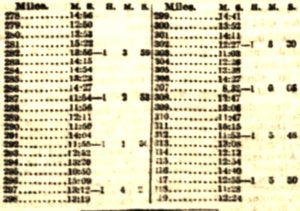

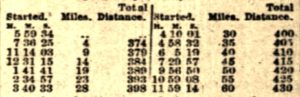

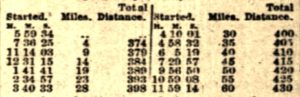

Weston’s Walk Progress

The Final Miles

“The crowd by this time nearly filled the available space around the sides and in the center of the hall, the boundaries of the track being almost broken down by the press of those who wished to catch a glimpse of the pedestrian as he passed rapidly by them.”

Like modern crowds doing the wave, cheers and waving handkerchiefs moved in a wave, as he passed by around the hall. But at times progress was almost impossible because the crowd pressed onto the track and got in his way.

“As he completed his final 430th mile, he sank into a chair exhausted and entirely overcome. He was greeted with the wildest applause and an eager throng of spectators rushed towards the judge’s stand to congratulate him. Weston was so overcome that he could do no more than bow an acknowledgment, and by the advice of the doctors he was removed to his room.” He was carried by the police through the crowd, put to bed, and immediately fell asleep. His walking time over the 144 hours was 98 hours, 28 minutes.

Weston blamed his failure on a foot that was injured on Day Three. But most believed he had exhausted himself on the first day by walking 115 miles or by the sprints he kept doing to please the crowd. One critic called him “The Great American Fizzler.”

Critics

Who would be the first in history to reach 500 miles in six days? Others wanted to be the first. When would true six-day races be introduced? Stay tuned for Part 3 in the Six-day race history

The parts of this Six-Day Race series:

- Part 1: (1773-1870) The Birth

- Part 2: (1870-1874) Edward Payson Weston

- Part 3: (1874) P.T. Barnum – Ultrarunning Promoter

- Part 4: (1875) First Six Day Race

- Part 5: (1875) Daniel O’Leary

- Part 6: (1875) Weston vs. O’Leary

- Part 7: (1876) Weston Invades England

- Part 8: (1876) First Women’s Six-Day Race

- Part 9: (1876) Women’s Six-day Frenzy

- Part 10: (1876) Grand Walking Tournament

- Part 11: (1877) O’Leary vs Weston II

- Part 12: (1878) First Astley Belt Race

- Part 13: (1878) Second Astley Belt Race

- Part 14: (1879) Third Astley Belt Race – Part 1

- Part 15: (1879) Third Astley Belt Race – Part 2

- Part 16: (1879) Women’s International Six-Day

Sources:

- Andy Milroy, The History of the 6 Day Race

- P. S. Marshall, King of the Peds

- P. S. Marshall, Weston, Weston, Rah-Rah-Rah!

- Tom Osler and Ed Dodd Ultra-Marathoning: The Next Challenge

- Hartford Courant (Connecticut), Jan 4, 1861

- Maidenhead Advertiser (Berkshire, England), Jul 6, 1870

- The Leavenworth Weekly Times (Kansas), Nov 10, 1870

- New York Times (New York), Nov 21-25, 1870, Jun 8, 12-17m Jul 4, 1871, Apr 22, May 13, 17, Dec 20, 1874

- The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (New York), Nov 21, 1870

- The Titusville Herald (Pennsylvania), Nov 21, 1870

- New York Herald (New York), Nov 22, 1870

- The Baltimore Sun (Maryland), Nov 28, 1870

- Alexandria Gazette (Virginia), Nov 28, 1870

- The Waterloo Press (Indiana), Dec 1, 1870

- The Courier (Waterloo, Iowa), Nov 10, 1870

- The Sportsman (London, England), Dec 15, 1870

- New York Daily Herald (New York), Jun 4, 1871, May 17, Jun 18-19, 1874

- The Philadelphia Inquirer (Pennsylvania), Jun 13, 1871

- Intelligencer Journal (Lancaster, Pennsylvania), Jun 5, 1871

- Times Union (Brooklyn, New York), Jun 15, 1871

- The Tribune (Scranton, Pennsylvania), Jun 14, 1871

- The Younkers Gazette (New York), Jul 15, 1871

- The St. Albans Daily Messenger (Vermont), Mar 1, 1872

- The Intelligencer (Anderson, South Carolina), Aug 14, 1873

- Buffalo Morning Express (New York), Feb 14, 1873

- The Western Spirit (Paola, Kansas), May 1, 1874

- The Brooklyn Sunday Sun (New York), May 17, 1874

- St. Joseph Gazette (Missouri), May 17, 1874

- The Cecil Whig (Elkton, Maryland), May 23, 1874

- Altoona Tribune (Pennsylvania), Jun 18, 1874