Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 36:06 — 41.5MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

Both a podcast episode and a full article

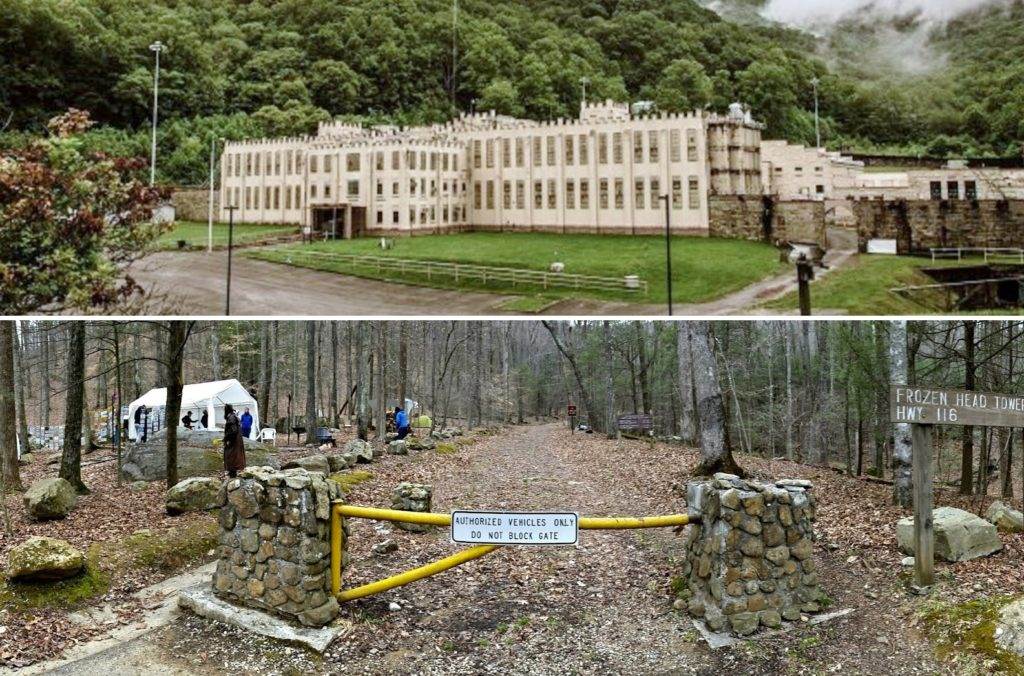

The Barkley Marathons, with its historic low finish rate (only 15 runners in 30 years), is perhaps the most difficult ultramarathon trail race in the world. It is held in and near Frozen Head State Park in Tennessee, with a distance of more than 100 miles.

The Barkley is an event with a mysterious lore. It has no official website. It is a mystery how to enter, It has no course map or entrants list is published online. It isn’t a spectator event. For the 2018 race, 1,300 runners applied and only 40 selected.

Those seeking entry must submit an essay. The entrance fee includes bringing a license plate from your home state/country. Runners are given the course directions the day before the race and aren’t told when the race exactly starts. They are just given a one-hour warning when the conch is blown. To prove that they run the course correctly, books are placed a various places on the course where the runners must tear out a page from each book matching their bib number. If they lose a page or miss a book, they are out. Directly opposite of most ultras, the course is specifically designed to minimize the number of finishers.

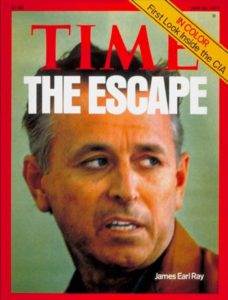

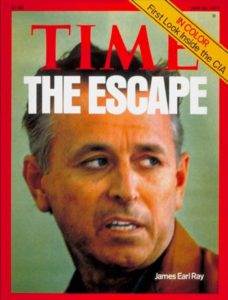

The inspiration for creating the Barkley in 1986 was the 1977 prison escape by James Earl Ray from Brushy Mountain State Prison. Ray was the convicted assassin of Martin Luther King Jr. He spent more than two days trying to get away in the very rugged Cumberland Mountains where the Barkley later was established. Ray’s escape has been a subject of folklore. This article will reveal the details of his escape, where he went, what he did, and why he was only found a few miles from the prison.

This is how the madness of the Barkley Marathons started…

| This history along with the early history of the Barkley Marathons, and the origins of other classic ultramarathons are now contained in a new book: Classic Ultramarathon Beginnings by Davy Crockett, available in your country’s Amazon site. |

Gary Cantrell (Lazarus Lake)

Cantrell’s masochistic race directing skills were further honed when in 1981 he put together “The Idiot’s Run” in Shelbyville, Tennessee consisting of 76 miles and 37 significant hills. He was surprised when several runners expressed interest. He said, “Is there no run so tough as to discourage these maniacs? If we had a 250 miler through Hell with no fluids allowed, I think we’d get 10-15 people.” A dozen runners showed up for The Idiot’s Run and only two finished.

The next year, 1982, he extended “The Idiot’s Run” course length to 108 miles and eliminated flat sections, gaining experience adjusting courses each year to make them harder. Cantrell explained, “The objective isn’t so much to see who finishes first as to simply see who survives for the longest distance. I’m confident this is the single grimmest race held anywhere in the world.” An article about his race was printed in newspapers across the country. Six of the twelve starters finished that year, the winner in 17:43:45, so it wasn’t really that hard. Cantrell could do better and did, extending the distance to 115-120 miles in 1984. Eight runners signed up that year.

Gary Cantrell and a buddy, Karl Henn (also known as “Raw Dog”) became intrigued with Frozen Head State Park in Tennessee where they had hiked many times during the 1970s. Nearby was the Brushy Mountain State Prison, the home of one of the most famous prison escapes in US history, James Earl Ray’s escape into the mountains in 1977.

To understand the complete history of the Barkley Marathons, one must know about the rugged mountains it runs through, the deep mines, the violent history of the prison that is part of the course, and the men in the past who chose to escape and face the rugged mountains that “eats its young.” The mountains, the mines, the prison, and the escape all played a part in the birth of the Barkley.

| There are now more than 150+ articles and audio episodes like this. Subscribe to the Ultrarunning History Podcast: https://ultrarunninghistory.com/subscribe-to-podcast/ |

The Cumberland Mountains

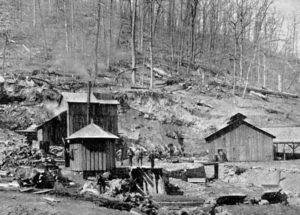

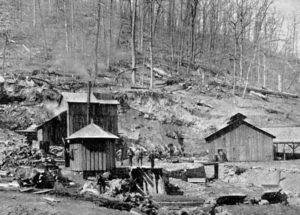

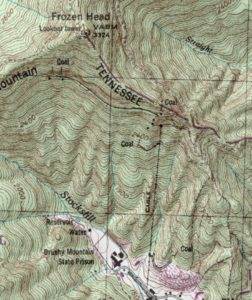

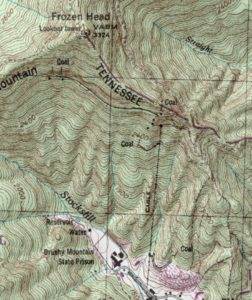

The Barkley runs in the Cumberland Mountain range in Tennessee which includes the Crab Orchard Mountains on East Tennessee’s Cumberland Plateau. These mountains also used to be called the Brushy Mountain range. Frozen Head is the highest mountain in the region. These mountains were made rugged by erosion of many streams that cut deep gorges. They are remote and challenging to travel through, and are known for their towering crags, massive bluffs, and dark caves. But there is something else about these mountains that paved the way for Barkley and its trails and roads. An old account said, “Buried in the bosom of this plateau are huge treasures of coal and iron.”

Brushy Mountain State Prison

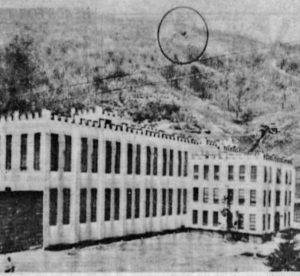

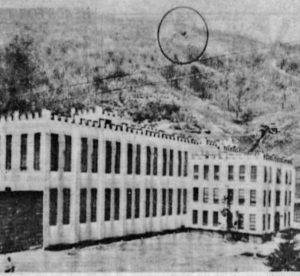

To get around this ruling, and to cut out the middleman, in 1896 the state got into the coal mining business which proved to be very lucrative. The state purchased 13,000 acres that included a good portion of the future Barkley course. They then used inmates to build Brushy Mountain Prison, a four-story wood structure and then made the prisoners do the mining in the mountains.

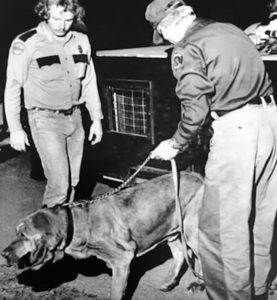

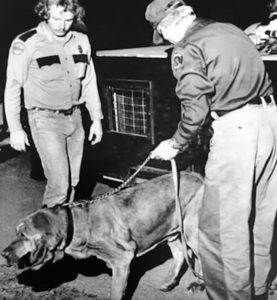

One piece of false folklore is that Brushy Mountain Prison was a very secure site, practically escape proof. That is false. Prisoners escaped all the time, but the mountains and terrain did present a challenging obstacle. Officials always downplayed escapes. “Most of the convicts who get away are recaptured, although it is a difficult matter to trace them through the forests and underbrush. Just outside the stockade nine bloodhounds are kept, and as soon as an escape is made, they are put on the trail of the fugitive and follow until he is found, or it is demonstrated that recapture is impossible.”

Quite a few men who escaped did suffer in the Cumberland Mountains like present-day Barkley runners. But many made it out of the rugged terrain. From 1922 to 2009 there were hundreds of escapes. Most of them were because the prisoners were constantly being moved to and from the mines, the prison farm, and the courthouses. But many escaped from the prison itself. They would escape on foot, in stolen cars, and in 1931 one even escaped on a mule.

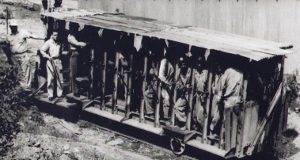

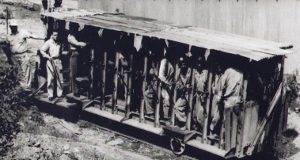

The Mines

Mining in the mountains near Brushy Mountain Prison was harsh, dangerous work and many prisoners died in them. Early on, thirteen died in just a 15-month period. These deaths were rarely reported in the news. The mining business for the stake was very profitable. In 1900 the mines brought in more than $175,000, worth more than 5 million dollars in 2018 value. The inmates built railroads and ovens to process the coal. Eventually more than 1,000 tons of coal was pulled from the mines each day. But it all came at a price. More than 400 bodies are buried on the prison property.

The governor was delighted with the operation in 1907. “The Brushy Mountain mines are in a more prosperous and profitable condition than ever before in their history. More coal is being mined, shipments are larger and more prompt and prices are better, while expenses are relatively less than ever before. It costs the people just as much to keep the prisoners in idleness as it does to keep them at work. Unless profitably employed, they would be an enormous burden on the State.”

The 1933 Mutiny

In 1932 former inmates wrote articles about the terrible conditions at the prison. After working in the mines during the day, they would spend the night in the over-crowded disease-infested building. A 1931 investigating committee reported, “conditions at the state’s Brushy Mountain prison at Petros approach conditions which prevailed in the Siberian prisons under the old Russian regime.” The 35-year-old overcrowded wooden structure was a “dangerous fire hazard.” The new commissioner over prisons called it “one of the worst things in the state.” More than 900 inmates were held there.

In 1933, 182 prisoners rebelled, barricading themselves in a tunnel and refused to come out. They were protesting treatment from the prison guards. Flogging was known to be frequent. State Commissioner of Institutions, E. W. Cocke said, “We plan to just starve them out. They will come out sooner or later. We don’t expect any violence or serious trouble.”

Authorities gave an unbelievable reason for the mutiny, that the prisoners were upset about a recent search conducted by the new warden that confiscated “files, hammers, and other weapons” from the men in the prison.

By the evening of the second day, all but 17 inmates came out of the mine. The next day, the remaining men gave up their strike. The prison warden resigned because of the strike two days later. Shamefully prison officials stated that the leader of the strike was diagnosed through a blood test as being insane and was shipped off to a mental institution. The event did spur a new effort in the area of prison reform and improving conditions.

The new prison

The 1938 Escape

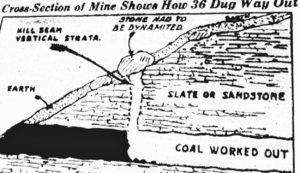

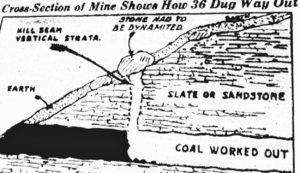

On March 27, 1938, a large number of prisoners from Brushy Mountain escaped from a coal mine located on Frozen Head where the Barkley course runs. Because the mining was so profitable, inmates were forced to mine even during the night, but were incentivized with payment of 25 cents per ton of coal. Eighty-five men were working the night shift. The guards didn’t go down into the mine but a foreman was supposed to be watching over them. However, that night the foreman was fast asleep. The prisoners had discovered a soft seam of coal about 1.5 miles into the mine. They dug a 30-foot shaft that was two-feet by two-feet and then used some dynamite to blast the final opening out on the mountain slope.

The alarm was sounded and continued for hours. Posses were formed and they unhappily trudged into the rough mountains. Civilians quickly joined in, including mountaineers led by bloodhounds in the “untracked wilderness.” The warden said that the escapees were “scattered all through the mountains but we’re going to bring them back.” The news reported, “The small army of more than 100 volunteer deputies armed with squirrel rifles, shotguns and even pitchforks spread a 20-mile ring around the prison in the event that the men had hidden in the vicinity.”

By the evening, 17 had been returned to their cells. Some of them “trudged back to the prison on their own free will and surrendered” after struggling on the Barkley course. They chose to return rather than further suffer from exposure and hunger in the mountains.

Dressed in prison stripes, it was feared that the convicts might raid homes to obtain civilian clothes. Every light in the town of Petros burned throughout the night and residents who remained in town stayed up fearful through the night. It was discovered that some of the prisoners took sticks of dynamite with them which heightened the danger of the chase. Warnings were broadcast as far as 70 miles away.

By the next day, twelve more men had been captured without firing a shot. Local residents were helpful catching the escapees. “Uncle Ike,” a man in his 60s, was at home sick with pneumonia when he encountered four inmates and held them at gunpoint until the authorities arrived. Two escapees successfully made in through the back country and fled into Kentucky, about 50 miles away where they were caught.

After 60 hours, seven remained at large and another was found the next day. One of the six surrendered more than a month later in Denver, Colorado who said he had been all over the country but was hungry, broke, and tired of dodging the law. It is unknown if the other five were ever apprehended.

The Tragic 1940 Escape

More than 100 people scoured the tough Cumberland Mountains near the prison but after a day the warden called off the search and said, “I have given up hopes of catching Overby immediately and must conclude that he has made good his escape.” Overby, a terrible man, had previously escaped from a Georgia chain gang where he had been serving a life sentence for murder. Overby was eventually caught, given 10 more years to has jail time. He killed two more men while in prison and in 1964, after another escape from Georgia, was recaptured and admitted that he had been the one who killed the guard at Brushy Mountain.

Other Events

Guards in the prison were a rough bunch. In 1949 two guard who were said to be good friends were in a guard house on top of the prison. They had an argument, took out their guns and shot at each other. Both were wounded and one man died from being shot in the stomach and chest. The surviving guard was found innocent of murder because the other man was beating him and shot first.

During the winter of 1950, soaking rain caused a massive mudslide to descend down Frozen Head. It was about a half-mile long and 100 years wide. It ripped out trees and brought huge boulders down toward the prison wiping out two mines. At the bottom it took out the road leading toward the prison making it impassible. The prisoners were immediately assigned to the difficult work of clearing the rubble.

Violence also occurred deep in the mines. That year four inmates tried to kill another man, John C. Farmer, by tying dynamite caps to his arms, legs and even one on the back of his head. Farmer managed to shake off the explosive on his head, but the others went off. He was taken to the hospital with mangled arms and leg. Later the next year the governor granted Farmer a pardon from his 3–5-year larceny sentence due to his “serious and permanent” injuries.

Brushy Mountain was once referred to as the most violent place in Tennessee. In 1950, the warden admitted that they whipped prisoners. “We use it infrequently and only for such offences as escape attempts. The whippings are not brutal, usually about eight licks.”

Each year prisoners continued to escape but frequently they were found within a year in other states. The prison included many very bad men. Oakley Hewgley, escaped in 1951 but was found about a week later in Kentucky. Two officials went to take him back to Brushy Mountain. On the way back, they stopped at a restaurant and Hewgley convinced them to take off his cuffs to eat. He seized one of their guns and tragically killed both of them. As hundreds searched for him in the hills, he walked into a police station, surrendered, and admitted to the murders. He said he hadn’t planned to try to escape from the men or kill them but explained, “I hated to be going back to Brushy Mountain. I dreaded it more than anything.” He instead went to prison in Kentucky with two life sentences for the murders and ten years later hung himself in his cell with pants.

The 1958 Prison Riot

By morning, guards armed with tear gas guns came into the debris-strew cell block and brought all the prisoners to breakfast. They didn’t resist. Outside the block other guards were armed with sub-machine guns and sawed off shotguns making sure another riot would not take place that morning.

News of the riot was widely covered in newspapers across the country. The Stake Corrections Commissioner negotiated with the prisoners who were protesting cruelty and “unequal treatment of prisoners.” A prisoner spokesman reported, “They gave us everything we asked for except two things, they wouldn’t give us a five-day work week in the mines and they wouldn’t agree to stop using the strap.” The prison was damaged totallying to about $5,000.

Hostage Protests

A few months later 116 inmates seized four mine foremen in a mine and held them hostage. The mine was about 3/4th of a mile from the prison. They immediately released one foreman to inform those outside what was going on. The message they gave was that they were not going to work and would hold the hostages until further notice. After 26 hours they released a 63-year-old foreman who had become ill and they said he was too old. He said of the prisoners, “It was the quietest crowd I ever saw. They just lay around sleeping or talking.” They had not done any damage. After 32 hours they ended their rebellion, came out, and marched back to the prison. The warden claimed that eleven booby traps and been left behind, rigged with dynamite and batteries from their mine-cap lamps. Eight “ring leaders” were punished and transferred to a maximum-security prison.

Another protest took place in 1964 at a mine on Frozen Head. On a morning the mine workers took cable cars 3/4th mile up the mountain and went another 3/4th mile into the mine to work. Six hours later guards outside of the mine were puzzled that no coal had come out of the mine. The prisoners inside used a mine telephone and informed authorities that they had taken three foremen hostages and that they wanted to talk to the postal inspector. The main grievance of about 40 of the 134 prisoners in the mine was that prison officials had been withholding mail. Deep in the mine hostages were told, “We won’t harm a hair on your head,” but they were warned that they had rigged some dynamite blow if they dared trying to get out. A hostage said, “They were nice to us, they offered us candy and coffee and stuff to drink. I wasn’t frightened, but I was cold and hungry.” Three inmates negotiated with the state corrections commissioner who agreed with their mail complaint. After 18 hours the revolt ended. The warden soon resigned and 18 or the revolting prisoners were soon transferred to another prison.

Mining concludes

In 1966 a cave-in occurred in a mine where 80 prisoners were working. It took work crews an hour and a half to reach the men who were nearly a mile down in the mine. Two men were killed, and two others were injured. One of the injured said that the roof just came tumbling down around them and trapped them beneath tons of dirt and rock.

The warden seemed to just brush it off and said, “it was just one of those things which happen in a coal mine.” Sadly, the two dead men had been in prison for petty larceny but as a result of the cave-in were given a death sentence. Thankfully, this helped accelerate closing down the mines in 1967 and for the state to pull out of this harsh system. The commissioner said, “We are losing money in our coal production there and it was decided we would pull out. Besides, the purpose of prisons is to rehabilitate men.”

The prison was still a very harsh place in 1969. Seven Brushy Mountain prisoners testified in front of a state senate committee. One inmate, Wilkerson, said, “When they sent me over there I got the impression that we were just sent over there to die, and there was nothing to hope for. I finally came to the conclusion that the only way to get out is to go over the wall.” Over the wall he went, and was free from about 10 hours, But because of the harsh terrain, like future Barkley runners, he broke some bones in his foot causing him to DNF. Eleven guards resigned as a result of the investigation.

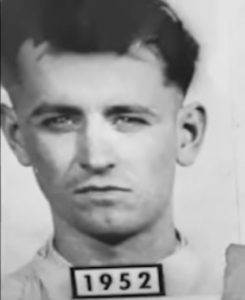

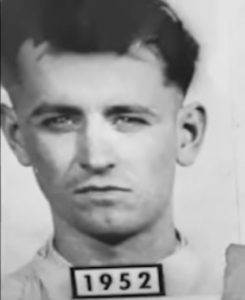

James Earl Ray

In 1970, once Ray’s appeals were rejected, he was sent to Brushy Mountain Prison on March 21, 1970, under heavy guard and during the night. The warden said Ray was “just another prisoner” and bragged that he had never lost a prisoner by escape. Ray, age 42 was initially given the job to sweep and clean the cell block and pass out tin plates of food to prisoners being transferred.

James Earl Ray’s 1971 and 1972 Escape Attempts

With Ray’s previous escape success in Missouri, he immediately sought to escape Brushy Mountain. On May 3, 1971, Ray made his attempt similar to the famed successful escape portrayed in “Escape from Alcatraz.” He used tools to scrape away cement from a concrete block in his cell wall and left a dummy in his bunk. He had obtained hair from the prison barber shop. He crawled out of his cell into an air chamber, and then ripped the bars from a ventilation fan, escaping into a prison courtyard. However, he made so much noise in the chamber that it alerted the guards who started doing a head count.

Ray then made a mistake and used the wrong concrete tunnel to crawl about 100 yards outside the prison walls. It turned out to be a tunnel from the steam plant and was nearly 400 degrees inside. He was only in the tunnel for about 10 minutes and suffered a few burns. A report explained, “Leaving his escape tools (a hammer, chisels and a crowbar) Ray huddled in the shadow of the prison’s cell block and tried to figure another way out.” The guards found the broken bars and he was caught at about 3:15 a.m. He offered no resistance when the guards surrounded him.

Ray had a history of bad getaways. After robbing a grocery store in Chicago, he fell from the getaway car and was captured. After stealing a typewriter in Los Angeles, he dropped his bankbook at the scene. After a Chicago robbery, he fled into a dead-end alley and was shot. Trying to escape the law in St. Louis, he jumped into an elevator but forgot to close the door and was dragged out.

In February 1972 Ray tried again. Guards caught him trying to saw a hole in the ceiling and roof of the prison gymnasium. The warden explained, “We had a couple of men get out that way before I became warden and I suppose he thought he could do it too.” Ray had obtained a hammer, makeshift saw, rope, block and bit and some plastic wood. He had cut through the ceiling of the room over a period of time while movies were being shown in the darkened auditorium. He used the plastic wood to put the cut board back into place and hide what he had been doing. It was believed that he had been working on it for some time. He was punished with 30 days in a “disciplinary area.”

Brushy Mountain Prison Shut Down

Later in 1972, 170 prison guards went on strike following disciplinary action against two guards. One guard had been fired for cursing at the warden, and another was reprimanded for leaving his post for more than an hour. The guards were in an organized union and the dispute couldn’t be resolved quickly. All of the inmates including Ray were transferred to other prisons within the state, most of them including Ray went to the state’s main penitentiary in Nashville. Ray was taken there under “very heavy guard.”

Before all the prisoners were transferred, with very few guards, five inmates used a rope to climb over the main wall and disappeared into the mountains. After one day, two made it to the town of Stephens about five miles from the prison. A woman spotted them from her doorway and shot at them. She didn’t know if she hit them. They were finally captured by deputies as they tried to hide behind a hours. The other three were discovered walking along the highway only two miles from the prison after being on the run for two days. They had not made much progress on the future Barkley course.

Brushy Mountain Prison was outdated, and the state contemplated shutting it down for good. Eventually Brushy Mountain was upgraded to a maximum-security prison and reopened in 1976. Ray was transferred back.

James Earl Ray’s Famous 1977 Escape

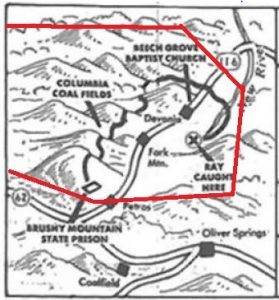

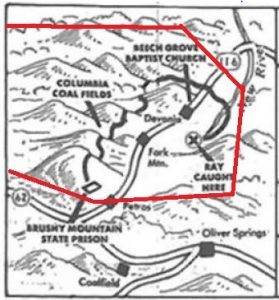

In 1977 mountains above the prison were referred to as the “third wall.” The prison warden, Stonney Lane, commented, “You might get over the first two walls, but you still have another huge wall to get over.”

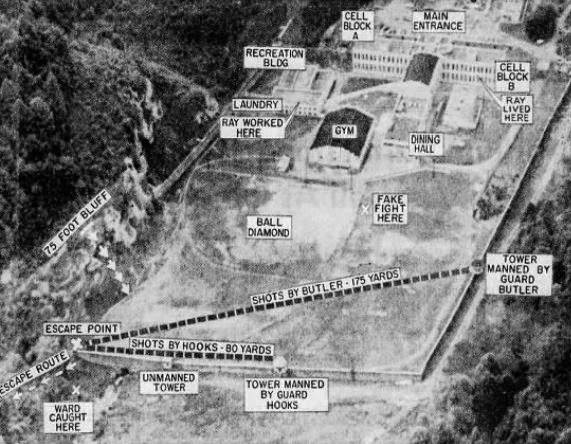

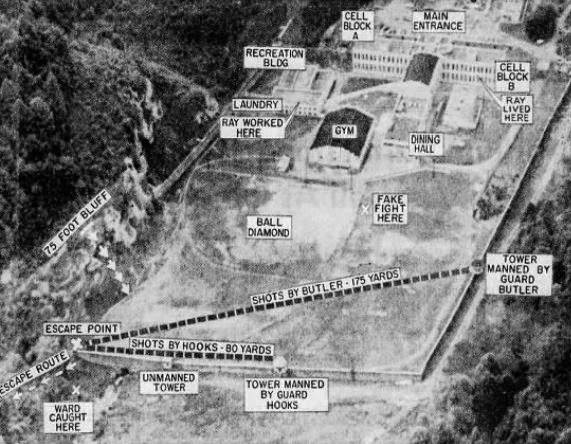

In June 1977, Ray successfully escaped the prison one evening before dusk, during a diversion, with five others. A fellow prisoner, Larry Hacker planned the escape and a fight was staged where guards rushed to the scene. A man fell down and faked a broken ankle. Another man faked like he was going to try to escape in another location and approached a wall. They weren’t allowed to be within ten feet of a wall.

Unseen over in the north-east corner, the escapees scaled a 12-foot wall on a make-shift pipe ladder that had been hidden in sections around the yard. The top of the “ladder” was in the shape of a semicircle to grab the wall and the bottom had T-bar like footholds.

They climbed the wall near a corner of the yard where the mountain slope met the wall. A wire carrying 2,300 volts of electricity toped the wall. The winter storms had caused the bluff to erode and had filled in an area. By running along the top of the wall they reached a part of the wall over which there were no wires.

The inmates knew that a guard at the nearest watch tower typically read a newspaper or slept. (He later claimed he tripped over his own rifle and locked himself out of his tower. He was subsequently fired). Ray went over the wall first. David Lee Powell, looked out the window of the prison dining room as he helped clean up from supper and saw five prisoners climbing up the wall. He ran downstairs and out the door in time to reach the ladder just as the last man scampered up. On his heels came Jerry Ward who decided to join in, too.

Soon a guard spotted the men escaping and shouted, “Look, over the wall!” A guard from a tower started shooting, first with a shot gun and then with a rifle. Ward was shot twice in the leg and fell over to the other side of the wall. The shooting guard could see the rest scrambling as hard as they could up the hill on the other side of the wall. He thought he shot another prisoner because he fell down the slope but then continued on. Ward was quickly captured. The rest had disappeared into the forested slope just twenty yards from the wall. Ward left the prison grounds in an ambulance, shouting all the way: “James Earl Ray got out! James Earl Ray got out!”

Local residents also headed into the hills with shotguns “for the excitement of the chase and the possibility of collecting the $25 bounty for each fugitive.” The national guard was eventually called up by the governor to help.

One searcher commented, “It’s harder at night, A man gets confused in those woods. He could fall over a mountain.” A plan was devised to flush out the escapees. They cleared the side of the mountain of searchers and dogs and then sent a group of men to the top of the mountain. The force would then move down the side of the mountain forcing the escapees toward the road at the bottom. Officers were placed every 100 yards along the road (State Road 116).

Around midnight of the third night, the bloodhounds picked up the scent of Ray and two others. They decided to split up. One man was quickly caught but Ray ran on for the next couple hours. It was reported, “Ray ran through the forest, his exhaustion overcome by adrenaline. He slid down a 20-foot embankment near State Road 116, a two-lane black top road that winds its way eight miles to the prison gate.” Actually, the distance is about four miles by car and 2.5 miles as the crow flies.

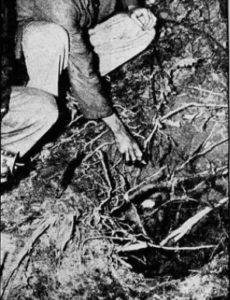

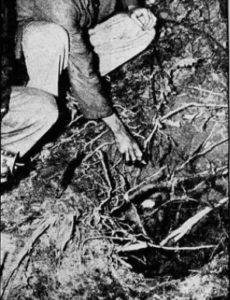

Ray crossed the road, slid down a 40-foot embankment and into nearby New River where he fell in the mud. He decided to circle back trying to confuse the dogs. He darted back into the underbrush, through a clearing and again into the safety of the trees.” He found a spot with leaves and brush and laid down. He frantically pulled wet leaves over most of his body. He was likely near the bottom of what became known as “Testicle Spectacle.”

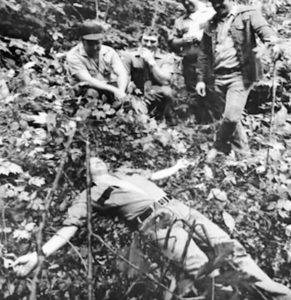

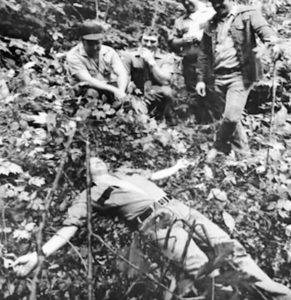

A dog had his scent and found him in a pile of leaves at 2:30 a.m. After 54.5 hours on the run, he was caught and immediately handcuffed and searched. During his escape he had covered at least 12 miles dodging his pursuers. Another escapee had made it to town before he was apprehended. A map was discovered on Ray, and it showed that he had made a wrong turn and went “too low.” The men were instructed that if Ray was found, they were not to blast the news over the radio because they didn’t want the FBI involved in the capture, so a code word of “Shiloh” was used to indicate that Ray was captured. The code name for Ray was “big apple.”

Ray was returned to the prison. Warden Lane had been confident that Ray would eventually come down from the rugged mountains. “It made no sense, no sense at all, for him to escape into those woods unless he had a way to get out of them.” He added, “none of the inmates are in here for using good judgment.”

A prison spokesman said Ray looked “like a pig wallowing in a sty” when he returned, “caked with mud, hair wet and matted, cut from briars and very hungry.” Back at the prison by 2:45 a.m., he was questioned, gave only one-word answers, given a medical exam, allowed to take a shower, and only given only a glass of fruit juice before bed. The next day he slept nearly the entire day and was fed better.

The search had cost the state about $200,000. Ray pleaded not guilty to the escape and a year was added to his sentence, to bring the total to 100 years.

When Ray was interviewed a few months later about his hours of freedom, he remarked, “That’s wilderness out there. I must have been in places that no human being has ever been. There’s heavy brush up there and things like that.” He only took some wheat germ with him and said, “I mostly thought about food, that’s the problem when you get out there. This time of the year, there’s nothing up there except green berries.”

Ray explained that he was in pretty good shape. “Everyone stays in real good shape. We all run laps around the yard a lot, there isn’t much else to do.”

Ray continued, “there are a lot of cliffs with ledges on them. You can sit under the ledges. There are coal mines up there, but it would be foolish getting into one of those things. That’s usually what they shake down first.” Drenching rain had slowed him down on the second day. He said of his capture, “I wasn’t happy about being run down. But the hunger really kind of dulls your emotions in some ways.”

James Earl Ray’s 1979 Escape Attempt

Ray tried again in 1978. Dummies were again used with hair from the barbershop. He and his cell mate scaled plumbing in what was called “the pipe chase” three floors to the roof and cut through an access plate to a small room containing a ventilation fan. After cutting a lock hasp off the door, they made it outside and then climbed down a pipe three stories, right beside the main door in front of the prison. The dummies worked and the guards didn’t know they were gone.

But an observant guard in a tower at the prison’s southwest corner spotted Ray crawling outside the base of the wall on his stomach under a green blanket being used as camouflage at 2:05 a.m. He was about 60 feet inside a chain link fence surrounding the building. The guard fired a warning shot and Ray stood up, offered no resistance as guards ran out and apprehended him. A prison guard stated, “The dummies were the best I’ve ever seen. One even had a foot covered with a sock sticking out from under the blanket. It was so good, you could see the outline of toes in the sock.”

Ray’s remaining years

Forming the Idea for the Barkley

In 1985, Gary Cantrell had been intrigued by the few miles Ray had covered back in 1977 during those 54.5 hours in the mountains, feeling that he could do much better. That year Cantrell and Henn went up into that wilderness to backpack, in two days, the “boundary trail,” about 20 miles, constructed by the CCC decades earlier. When they showed the rangers their route around the park, they were told that they wouldn’t be able to make it. The rangers didn’t want them to go on the hike because they didn’t want to have to rescue them. But the rangers were convinced to give them a permit. The first 7.5 miles took the two ten hours to cover. They did finish their backpack trip and told the rangers that they had some friends who would probably like to run the trail. The idea for the Barkley had been hatched.

Continued in Barkley Marathons – First Few Years

| There are now nine books in the Ultrarunning History Series, available on you country’s Amazon: https://ultrarunninghistory.com/urhseries/ |

The Cumberland Mountains

Sources:

- Back to Brushy Mountain: The historic prison’s past and future

- Outside Magazine, “60 Hours of Hell”

- Montgomery, Like the Dew, May 13, 2010.

- Playboy Magazine interview, September 1977, 94, 134.

- “How did James Earl Ray break out of Brushy Mountain State Prison?”

- WBIR Report: James Earl Ray escapes Brushy Mountain Prison

- The Leaf-Chronicle (Clarksville, Tennessee), Mar 18, 1931, Mar 11-14, 1958, July 13-16, 1959, Aug 29, 1982

- Kingsport Times (Tennessee), Aug 21, 1931

- The Daily News-Journal (Tennessee), 15 Aug 1933

- The Times (Hammond Indiana), Mar 28, 1938

- The Tennessean (Nashville), Mar 3, 1903, Jan 27, Nov 18, 1907, Mar 28-29, 1938, May 11-12, 1940, April 24, 1941, Jun 6, 1943, Oct 21, 1950, May 27, 1966, Jan 11, 1964, Dec 10, 1969, Jan 24, 1970, May 4, 1971, Aug 5, 1972, June 14,19 1977, May 4, 1979

- The Corpus Christi Caller-Times, 1 Apr 1938

- Kingsport Times (Tennessee), May 4, 1938

- Great Falls Tribune (Montana), Mar 11, 1958

- The Dispatch (Illinois), Mar 12, 1958

- Kingsport Times (Tennessee), May 26, 1966

- The Jackson Sun (Tennessee), Nov 26, 1964, Mar 25, 1970, Feb 15, 1972, Nov 11, 1979

- UPI story, June 11, 1977.

- Kingsport Times-News (Tennessee), Jul 23, 1972

- New York Times, June 13, 1977.

- New York Daily News, June 14, 1977

- Kingsport Times-News (Tennessee), Jun 11, 1978