Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 29:36 — 32.7MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

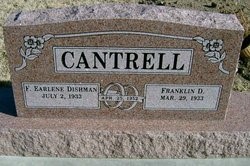

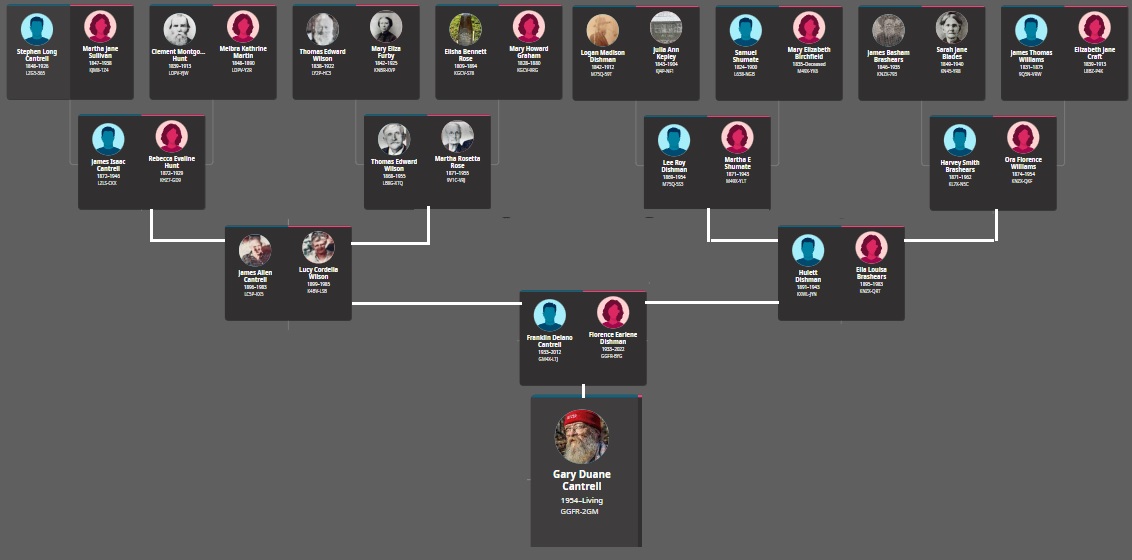

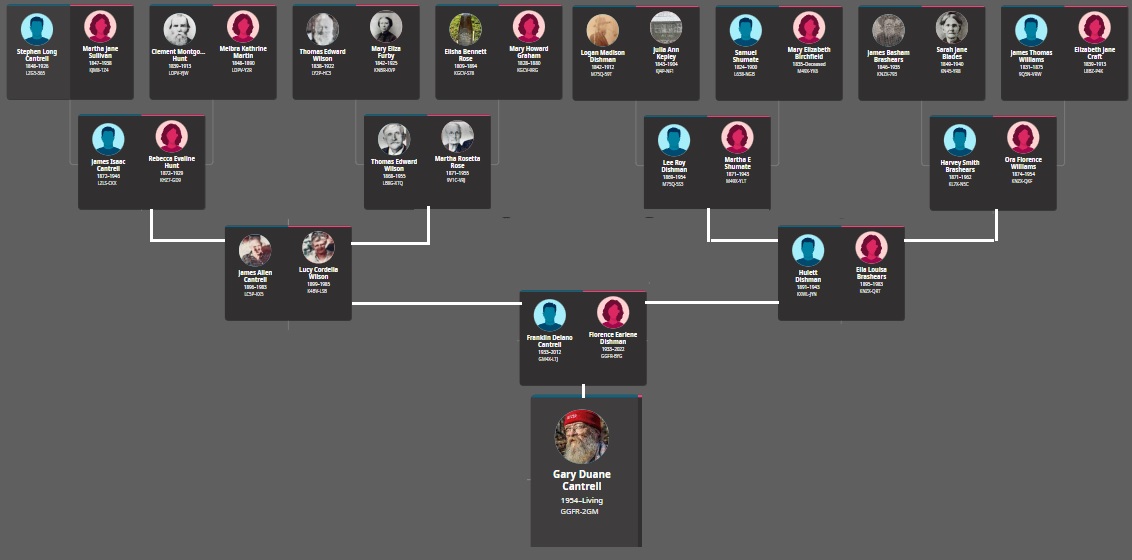

Gary’s Ancestry

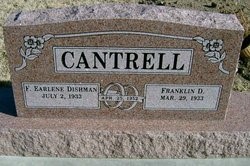

Gary’s ancestral roots were solidly southern. His Cantrells lived in Tennessee and Arkansas for generations. He had ancestors who were among the early Colonial American settlers.

His first Cantrell ancestor in America was his 7th Great-grandfather, Richard Cantrell (1666-1753) who emigrated from England to Colonial America in 1682 to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He was at first a servant to another man, probably serving an apprentice learning to be a brickmaker. It is believed that he made the bricks for the first two brick homes built in Philadelphia. Gary’s 4th Great-Grandfather, Thomas J. Cantrell (1761-1830) fought in the Revolutionary War for North Carolina and was the first Cantrell ancestor to settle in Tennessee. He operated “Old Forge” in Sink, Creek, Tennessee.

On Gary’s mother’s side, the Dishmans lived for generations in Missouri and Kentucky. His first Dishman ancestor in America was his 6th Great-Grandfather, Samuel Duchemin (1640-1727) from France. He came to America in about 1693, settled in Virginia, and Anglicized his name to Dishman. His grandsons fought in the Revolutionary War, including Gary’s 4th Great-Grandfather, Jeremiah Dishman (1752-1841).

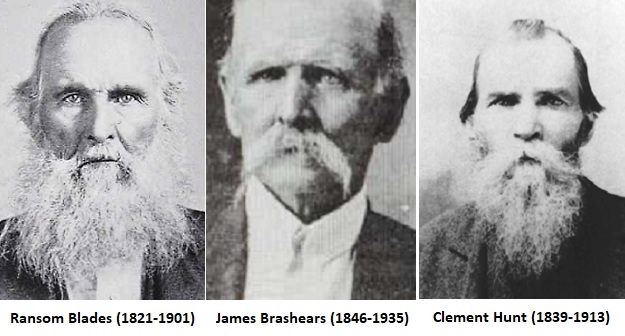

Civil War Ancestors

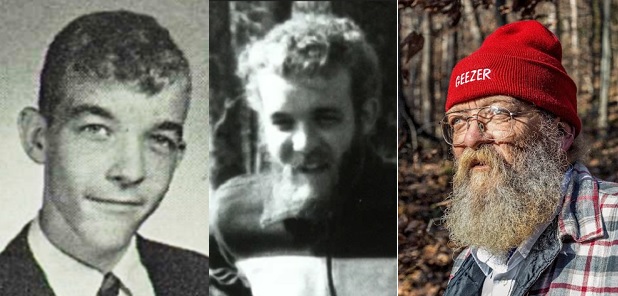

Childhood

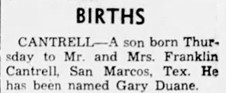

Gary’s grandparents were James Allen Cantrell (1896-1983) and Lucy Cordelia Wilson (1899-1985) of Arkansas. In about 1918, they moved to Oklahoma, in a covered wagon and raised their family there, where James worked as a laborer on an oil rig and then farmed.

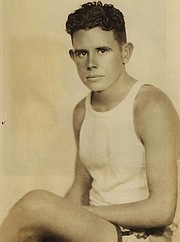

Gary’s father, Franklin, grew up working hard in the fields using mules to plow. as a child, he attened school in a one-room schoolhouse that he rode a horse to and from. He loved to hun and fish and work with the animals on his farm. He was an outstanding athlete and a star on his sports teams. His farm was next to the farm of Andy Payne (1907-1977), who won the 1928 race across America (The Bunion Derby).

Gary’s father knew him well and told Gary many stories about Payne’s famed run. He went to a trade school to become an aircraft mechanic. After marrying Florence, he joined the army where he used his aircraft mechanic skills, and continued in the profession after being discharged. Not content in being just a mechanic, he enrolled in college while working fulltime, eventually getting a degree in aerospace engineering and got a job at Douglas Aircraft.

Running Across a Pasture

As a child, Gary would enjoy hunting with his father and grandfather in the outdoors. At age nine, in the early 1960s, Gary did some running whether he liked it or not. “I used to have to feed the cows before I went to school. This entailed about a quarter-mile walk across the pasture to the barn. We had this heifer that was just plain mean. She became the terror of my existence, to the point that I no longer dared to walk across the pasture, but would walk through the neighboring woods and cross the fence close to the barn and make a mad dash to the barn. I told my dad daily that the cow was going to kill me, and he would scoff and tell me that cows are afraid of people, just act confident.” One day, because he overslept, his mom did the cow feeding duties. After he came home from school, Gary found her trapped in the corncrib, cornered by the mean cow. The next morning, his dad accompanied Gary to feed the cows. “We walked brazenly out into the pasture, Dad in front (with a baseball bat behind his back) and me behind. Sure enough, my nemesis came running, ignoring dad, while trying to circle around to get at me, until Dad whipped out the bat and landed a prodigious blow square in the center of her forehead. Her knees buckled. I swear her eyes crossed for just a moment, and then she regained herself enough to take off running. For the remainder of the fall, I made my trips to the barn without incident.”

Childhood Games

His family moved around quite a bit in Oklahoma. He ended up going to ten different schools. While living in Norman, he became a big Oklahoma football fan. He lived right off campus and the married football players living in housing all around him. He spent a lot a time with the players as they would take him places. His Sooner fandom lasted all his life.

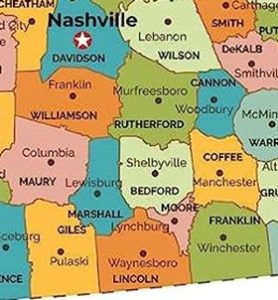

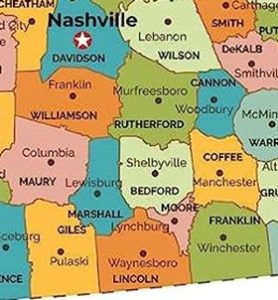

His childhood was filled with activity. He once described a favorite grade school playground game called “white horse,” requiring partners. “One boy rode on the other boy’s shoulders and you tried to put other teams out by either knocking them to the ground or dislodging the rider. I teamed up with a guy named Gary Welch, and we were almost unbeatable. He was the biggest kid in the school, one of those guys as wide as he was tall. I was the smallest and rode atop his shoulders like a pet monkey. Actually, I was more of a human grappling hook. I held on to Gary with both legs and one arm, and used my free hand to grab hold of any part of the opposing team. Once I got a grip on something, Gary just took off at an angle, and the irresistible force of his weight brought the other team down.” When Gary was 12, his family moved from Oklahoma to Tullahoma, in middle Tennessee, where Gary’s father worked as an aerospace engineer for Sverdrup Technologies. He would later help design the propulsion systems for the eagle lander that landed on the moon.

Running Beginnings

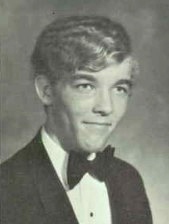

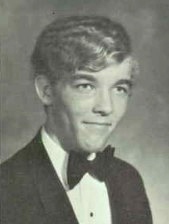

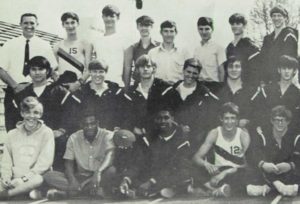

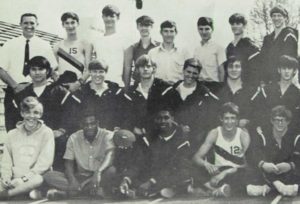

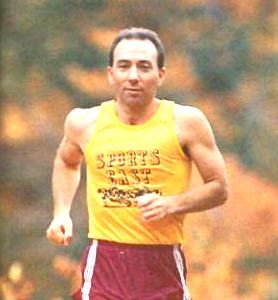

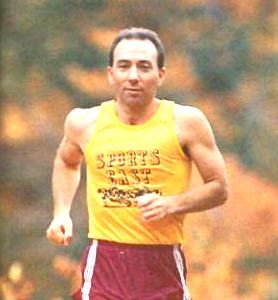

He further explained, “I’m a runner because I failed as a football player. My family was very sports oriented, and I always thought that I would play some sport. Football was my number one sport. When I started 10th grade, at Tullahoma High School, I was only 5 feet tall and weighed 70 pounds. I wasn’t fast, and I wasn’t strong. So, there were really no sports options available to me. Even wrestling where they have weight classes, the smallest class was 90 pounds. So my options were pretty much running. I went out for cross country and made the team. I persevered enough and had pretty moderate success. Our team was really good and went to the state meet every year.” He was toughened up from running cross country. As courses passed through woods out of sight, competitors would “jostle” each other and hitting the ground was common. “If you wanted to pass, you had to be alert for an elbow to the chest.” He also was on the high school track team. His most prized award during his running career was a trophy presented to him as the most dedicated runner on the team. His next favorite was a gold medal won for a two-mile relay during his senior year. He said, “We went through hell together to earn it.” His experiences in high school sports would lead to a lifetime of coaching youth in many sports.

Running in Memphis

In the early 1970s, for three years, he worked in Memphis, Tennessee, living in the Orange Mound area. He ran out on the roads but he never saw anyone else doing it until one day he saw a guy a couple of blocks ahead of him who was running. “I thought, ‘he’s running!’ So I ran really fast to catch up with him and managed to make the corners fast enough to see where he was going and ran him down. He said, ‘Oh yeah, running is exploding. We even have a club.’ So I joined the Memphis Runners, and I was member number 12.” The club would hold informal races each Saturday. “We’d meet at the Memphis state building, pick a course, and hide a stopwatch in the bushes. Whoever got back first pulled out the stopwatch and called out everybody else’s times.”

Streaking at Night

He mostly enjoyed running in mid-town Memphis, where there were many nice old houses and quiet boulevards. One late night, while having beers with his track buddies, they talked about the Greek Olympics in which they ran nude. They wondered what it would be like. At 3 a.m., off they went to the track and ran a nude 440. “Everyone ran really fast, because the further you go from your clothes, the less you wanted the other guys to get back to them before you did.”

Dodging a Motorcycle Gang

One day, Gary was running through Audubon Park in Memphis. A motorcycle gang approached and purposely swerved over, causing him to jump into a ditch and then showered him with dirt and gravel. They went on and he climbed back on the road and continued his run. But later they came back again and repeated the deed. They clearly were circling the park, having a great time watching Gary jump. He ran as fast as he could to get away, but then they found him and came at him again fast. “Just then, the lead rider slipped in the gravel and went down. The guy right on his tail went down as well. Two riders and two bikes bounced along the road.” The men were a bloody mess and their machines were a tangle of metal. A crowd gathered. Gary was careful to just watch. An ambulance finally arrived.

| Get Davy Crockett’s new book, Classic Ultramarathon Beginnings that covers the amazing early years of nine classic ultramarathons, including a 50-page chapter on the Barkley Marathons. Available on Amazon. |

Marathon Runner

But the more he raced the shorter distances (3-5 miles), the more discouraged he became about his results, even though he usually finished in the top 10 percent of his races. “After high school, I had not achieved the success I wanted. I thought I would run longer races because I had stayed in good condition and I could endure a lot of punishment. So I worked up to the longer races, road races, and marathons.”

In 1974, at the age of 19, he married his first wife, Mary Catherine Wells (1955-). She also became a long-distance runner and would compete in ultras for about eight years, including some of Gary’s races, usually beating him.

In about 1975, Gary became a “streak runner,” running at least a mile every day. His streak would last into the 1980s, for at least 3,500 days. He would run when it was 105 degrees or 20 below zero, in sleet, hail, thunderstorms, and even the day after knee surgery.

That year, he ran his first marathon at the Andrew Jackson Marathon in Tennessee. On race day, he woke up four hours early, ate five ham sandwiches, and then ran in 3:20. He said, “I felt so proud. I was so ecstatic. What a thrill. I had done it. A marathon, wow, incredible. It was one of the highlights of my life.”

In 1976, he ran his first ultra-distance training run of 30 miles to get ready for a marathon. The first time he heard about ultras, he said, “That is just stupid. I will never do it. The marathon is enough pain that anyone needs to suffer.” However, he would continually move up the distances of his races, hoping that he could compete better. He knew he wasn’t exceptionally fast, but he was durable. He began running without socks and did so for decades. His feet would do great, but his shoes would “smell worse than week-old roadkill.”

Running all the Roads in Counties

While many detested running when it was hot and humid, those conditions became Gary’s heaven in rural Tennessee. “I loved the feeling of sweat pouring down my body, dripping from the brim of my hat and the bottom of my shorts. The coolness when any breeze hit the moisture, and the ecstasy of running into a long stretch of shade. I treasured stopping at some farmer’s spring house, standing in the doorway with the cold air rushing over my skin and dipping a mason jar of sweet cold water.”

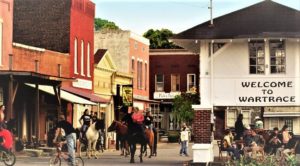

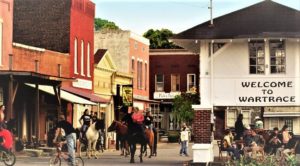

Founding of Strolling Jim 40

In 1978, Gary was a 23-year-old accounting student at Middle Tennessee State University in Murfreesboro, weighing in at a slim 150 pounds. His accounting background and love for numbers would influence his approach to running and putting on races. He was now a tough marathon runner with eight finishes to his name, training about 10 miles a day with a long 30-mile run every other week. He never was a fan of running in the morning, preferring to run in the afternoon. His marathon times had plateaued. He was interested in stepping up the distance and run in an ultramarathon. He set his sights on the Stone Mountain 50-miler near Atlanta, Georgia that had been won by Park Barner (1944-) in 1977. However, the race was cancelled in 1978 because of a lack of interest. The next nearest ultras were far away in New York City or Philadelphia. He recalled, “I was talking to some of my running companions here in the area. There are about 10 or 12 of us, and we call ourselves the Horse Mountain Runners. We decided to hold our own ultramarathon and hold it in Wartrace, Tennessee, because it’s such a nice town and a lot of us do our training in that area.” Wartrace was nicknamed the “Cradle of the Walking Horse.”

This was Gary’s first experience in creating a tough race. His friend John Anderson (1950-) explained, “Gary and I wanted to run an ultramarathon and so we decided to put on our own. He got out the map and lined out a course. At first, I thought we should call it the ‘Idiot’s Run,’ but I believe Gary came up with a more appropriate name.”

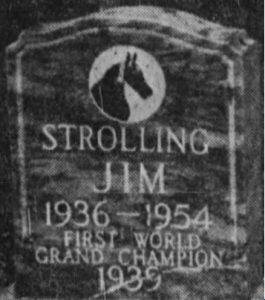

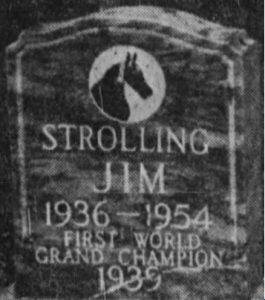

Who was Strolling Jim?

The race was named after a famed horse, Strolling Jim, hoping to generate local support. Strolling Jim (1936-1957) was the first Tennessee Walking Horse to become a National Grand Champion show horse for his breed. He died in 1957 and was buried by his stables behind the Walking Horse Hotel, where the pre-race spaghetti dinner would be held with some live bluegrass music entertainment.

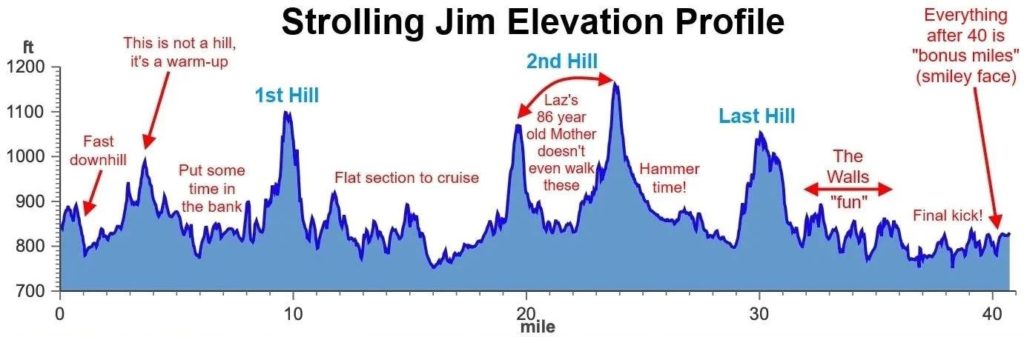

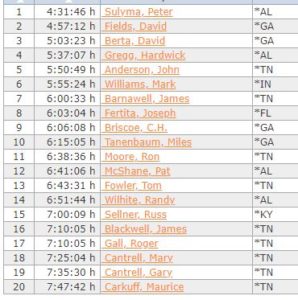

The Strolling Jim 40 Mile Run

In promoting his new road race, The Strolling Jim 40, Gary said, “The course is mostly hills, and I believe for a runner to finish the race, it will be less what’s in the legs and more of what’s in the mind. It is about 90 percent mental. It will pretty much be up to each runner to make it on his own. Runners will have to run with the course rather than at it. Six or eight doctors will be in the race and that sort of surprised me. You’d think of all people they’d know better.”

For that first year in 1979, Gary used streamers to mark the course and set out water jugs every five miles. But crews were also required to drive along and provide support. Twenty-two runners started that first year on May 5, 1979, and only two had finished an ultra before. Five had not even run a marathon. Gary’s race director humor began during this first race. Jared Beasley explained, “The course was full of tongue-in-cheek humor. Multiple signs spray-painted on the route read, ‘this is not a hill.’ Finally, runners reached an even steeper climb, where they found another sign: “This is a hill.’”

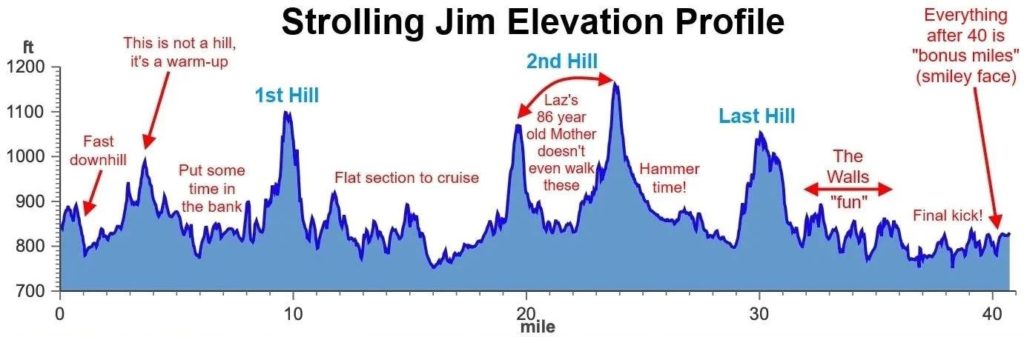

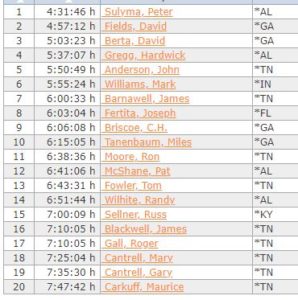

Peter Sulyma (1945-) a NASA aerospace engineer, of Huntsville, Alabama took the lead, hit the marathon mark in 2:45:23 and finished first with 4:31:46. The only woman finisher was Gary’s wife, Mary Cantrell (1956-) in 7:25:30. She said, “I began doing more training than Gary was and I thought to myself, ‘Well, if Gary thinks he can do it, then I believe I can too.’ I guess I just got caught up in the excitement of it all and maybe I’m a little crazy.” She had been training 60-70 miles per week and had previously finished three marathons.

Gary finished ten minutes later for his first ultra finish. Only two runners did not finish. Despite the difficulty of the race, with 90 hills, Strolling Jim 40 continued to have a high finishing rate in the years to come and grew in popularity. Gary quickly understood how difficult it was to run a good race when you had to also direct it. Crews would often drive up and ask him questions or tell him about race problems as he was trying to run, making it so he couldn’t concentrate on his own race. After running in the race for four years, he stopped to do full-time race directing.

Gary Shot During a Marathon

Gary continued running marathons. His lifetime personal record (PR) was 3:15 when he got food poisoning and lost 17 pounds before the race. He hoped to break three hours but had bad luck all the time with the weather. His PR for a half marathon was 1:19. He downplays how fast he was at the shorter distances, but he did break five minutes running a mile. His PR for 10K was 38:09.

In November 1979, while running a marathon in Chattanooga, Tennessee, he was shot! It was reported, “Police said a runner in a marathon race was struck by shotgun pellets, but not seriously injured, while running near a wood area Saturday. The runner, 25-year-old Gary Cantrell of Shelbyville, finished the 26-mile race. Officers said the pellets struck Cantrell in the legs and he was treated by paramedics at the scene and was not hospitalized.” It turned out that hunters in the area were shooting at quail. They were questioned and made to move back further into the woods. It was believed that it was an accident, but perhaps a future Barkley runner found a way to travel back in time and get a little revenge.

Eric Clifton Meets Gary

Ultrarunning Legend and fellow hall-of-famer, Eric Clifton (1958-) met Gary for the first time in July 1980, at Grandfather Mountain Marathon in North Carolina. Clifton and his wife Shelby had finished the race and were standing where runners entered a track for a finishing lap.

“We saw this blond-haired guy come jogging up, and he stopped right at the entrance to the track. He reached into his pocket and pulled out a packet of cigarettes. He took a cigarette, stuck it his mouth, held a lighter, but didn’t use it yet. He stood there, and we asked, ‘Aren’t you going to finish?’ He said, ‘yes, I’m waiting for a woman to come in.’” In those early days, women running marathons were still a rare sight, and he knew the next woman finisher would get huge cheers as she ran around the track. “So a girl came running up, and he tucked in behind her. He lit his cigarette and started smoking behind the woman. The huge crowd started cheering for her and he was smoking his cigarette, waving, taking in the cheers, but stayed behind her. He knew it was a great way to get accolades.”

Thirty years later, Gary found a box of letters from the 70s and 80s. One read, “I met you at Grandfather Mountain and I am very interested in this ultramarathoning thing. Where can I get more information? Eric Clifton.” They must have communicated further. Two years later, Clifton ran in his first ultra.

Running Ultras

Gary was still trying to figure out how to run ultras well. He said, “It was either 1979 or 1980 that Tom Osler changed my life. I read some article, either by or about him, that introduced a concept so revolutionary that it completely redefined my capabilities. Walking was not just what happened when you could run no further. It was acceptable to walk on purpose and if you mixed in a little walking as you went, your horizons expanded beyond the horizon. Suddenly, I found that I was not limited to 30 or 35 miles in a run. I could go on and on indefinitely.” In 1976, Tom Osler (1940-2023) proved the run/walk theory by doing a 100-mile in 18:19:27 on the track at Glassboro State College in New Jersey. His running techniques were published in 1978 in the Serious Runners Handbook, which sold more than 55,000 copies. Gary further recalled years later, “His revolutionary ideas about incorporating some walking opened up new horizons for me. I was pretty well stuck on how to get past 50 miles because that was about as far as I could run without having to walk. It sounds strange now, but at the time I thought if you had to walk, you might as well stop.”

In early 1980, Gary competed in the 50-mile road race in Atlanta, Georgia, that had been cancelled in 1979. The course was a hilly ten-mile loop and the six starters faced surprising 32 degree temperatures. “We had heavy winds and mixed sleet and snow all day. Ice kept forming on my eyebrows, then gradually growing until the ice ledge started to block my vision, and I would have to break it off.” He did well, finishing in 8:46:18. The race was won by fellow-southerner, Ray Krolewicz (1955-), of South Carolina, who had started running ultras just eight months earlier, at Lake Waramaug, Connecticut, on the exact same day that Gary started his ultra career at Strolling Jim. Gary would call Krolewicz, “the young lion of our sport.” At another race in Florida, Gary recalled, “I remember young Ray rolling along and performing his reversal of the famous ‘evolution chart,’ as he went from erect to knuckle dragging as the miles mounted.”

Gary ran his first 24-hour race that year. He had been warned about experiencing hallucinations during the night, so he was fully prepared when he started seeing tiny frogs appearing on the dark end of the track. He recalled, “Lap after lap, the little buggers seemed to be multiplying, hopping all over the place. Even though I was aware they were only hallucinations, they looked so real that I couldn’t help but hop-skipping around to keep from stepping on one. Finally, I couldn’t stand it anymore, so I stopped, bent over, and picked one up. There really were little frogs hopping all over the track.”

Attempt to Run Across Tennessee

Later in 1980, instead of running long roads in Tennessee counties, Gary got the idea to run across the state, from Alabama to Kentucky, about 125 miles. He got dropped off, and all he had was his running shorts, shoes, a t-shirt, nylon windbreaker, and some money to get food and drink along the way. He pushed the early pace so he could reach the next store before getting too thirsty. He did well for the first 64 miles. But as a big University of Oklahoma football fan, he had to stop at a bar to watch the game and was offered too many free beers. When he got back out, the weather was miserable and cold. He took old newspapers out of a machine and stuffed a bunch into his clothes to try to stay warm, but then they got wet. He said, “After making every mistake a noob can make, I ended up aborting after 93 miles. It was a failure that would give birth to the Vol-State.”

One year, while training for a long race, Gary tried to run a streak of 20 miles every day for 22 days. He recalled, “The streak ended at 14 days with a bad dog-bite to my calf. It wasn’t so much the punctures and tearing to the muscle, as the total bruising of the calf that did me in. I lost the rest of my training, and the race.”

Nick Marshall Track Run

In 1981, the race was held again but turned into a 24-hour run, held at Gary’s old high school in Tullahoma, Tennessee. Ray Krolewicz won among the ten starters with 114 miles. For 1982, in typical strange Cantrell humor, the winner, Nace Magener with 136 miles, was awarded the “Nick Marshall Cup.” Nick Marshall explained, “The award consisted of a genuine used Nick Marshall jockstrap which Gary had me send to him. It took some digging in the attic to come up with such a relic.” For 1983, the entry form began, “Glamour! Pageantry! Big Stars! Live TV Coverage! Throngs of Admirers!!! You too can avoid all these things by joining us.” Nick Marshall finally participated in his name-sake race by hitch-hiking 800 miles to the race.

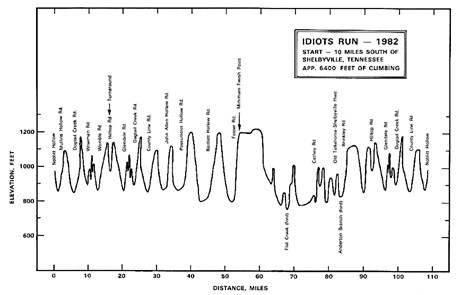

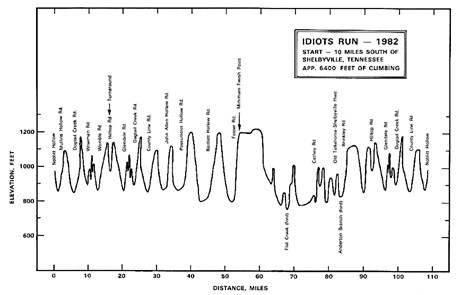

The Idiot’s Run

The next year, September 4, 1982, Gary, now a veteran of 32 marathons and 17 ultras, extended “The Idiot’s Run” course length to 107 miles and eliminated flat sections, gaining experience adjusting courses each year to make them harder. Gary explained, “The objective isn’t so much to see who finishes first as to simply see who survives for the longest distance. I’m confident this is the single grimmest race held anywhere in the world. There is a run out west known as the Western States 100, which was supposed to have been the most difficult, demanding ultramarathon. Well, our Idiot’s Run will be six miles longer than that, and the terrain will be just as rugged. The only difference will be the altitude. The course is an almost continuous string of steep and treacherous hills, and if we’ve had rain the week of the run, there will be as many as 18 creeks and rivers to cross. We’ll be going through some wild country, and much of it after dark. A run like this can destroy you, and simply tear you down.” An interviewing reporter said, “When Cantrell describes the run, his voice sounds eerily like Jack Nicholson’s in The Shinning.”

Pete Riegel (1935-2018), an engineer from Ohio, was one of the twelve starters that year. He said, “I like Gary a lot. He’s so laid back he may forget to breathe one of these days, yet he has found the mans to put on some fine races.” Ray Krolewicz (1955-) blasted into the lead from the start, but because of poor navigation, early on, he ran extra miles.

Nick Marshall (1948-) reported, “Earlier Gary had prophesied, ‘I always think that next time it’ll all go perfect. Sometimes it does, but not in the Idiot’s Run.’ Gary got to within ten miles of the end, was so tired by then that if it were the body of a mule that he was flogging forward rather than his own body, he would have been arrested for cruelty to a dumb animal.”

Animals were a feature of the race. Marshall remarked, “One facet of this type of running in the rural foothills that surprised the participants from more urbanized areas was the number of dogs along the route. It seemed every house had a large watchdog on the alert.” Marvin Skagerberg (1938-) from New York, roused a big dog at 1 a.m. when he went back and forth in front of a farmhouse, trying to figure out if he was heading the right way. The dog woke up the family. “Out in the dark, on a deserted country road, the man of the house had a friendly but understandably perplexed question for Marvin: ‘What the hell kind of walkathon you go going on at this time of the night?’ Skagerberg explained, ‘Why, actually sir, it’s not a walkathon. I came from New York to traipse more than 100 miles of your Tennessee hills for the fun of it.’”

Six finished the entire course. Kevin O’Grady (1958-), of Columbus, Ohio, won in 17:43:45, so it wasn’t really that hard. Gary made it tougher the next year, adding more hills. Only five runners started in 1983. Cantrell gave every runner the bib number of 4 that year because “this simplifies the results sheet.”

Seven started in 1984. Gary ran with Jack Fabian (1944-) from Florida. After about 24 hours, right after sunrise, Jack wanted to change all his clothes. They hadn’t seen a vehicle in ages, so Jack got in the buff. Gary said, “About the time he got totally buck naked, a pickup truck came over the hill directly in front of us. As jack hopped around on one foot, frantically trying to pull on his underwear and shorts simultaneously, the truck passed us. The elderly couple inside were obviously shocked. The woman’s eyes almost popping out of her head. The click of door locks was clearly audible. We ran the next 5 miles at world-class pace, wanting to get plenty far away before the county sheriff had time to arrive on the scene.” They finished in an unofficial 40:16.

1983 Ultras

Gary’s first marriage ended after only a few years and he next married Sandra Gail Eatherly (1958-) who he had originally met in an accounting class in college. “Cantrell wore his curly blond hair in a ponytail and sat in the far back of the classroom. Every time Sandra turned around, he would wink, tilt his head to the side, and stick out his tongue.” She would be his lifelong companion. She was involved in sports, keeping the score for the high school basketball teams.

Gary ran several other ultras that in 1983, including an indoor 48-hours race at Haverford College in Pennsylvania, a couple 24-hour races and the Edward Payson six-day track race held at Cooper River Stadium in Pennsauken, New Jersey. “Gary Cantell arrived in an overhauled Checker cab with his wife, Sandra and 16-month-old son Case.

They set up their yellow cabin tent on the side of the track where Sandra attended to a cooler of ice and soda and looked forward to a week of relaxing while her husband pumped his legs.” Sandra said, “I like it. I like the people.” But she wasn’t interested in running. “I ran a mile before I was pregnant. But I didn’t like that. It hurt.” Gary finished last, with 132 miles. His running goal was just to do better than he did before.

Running ultras in those days were simple for Gary. “I never carried anything, not even a handheld bottle. Aid stations were generally about 5 miles apart. If thirsty, I drank a lot when I got there. I remember at least one 50 miler with only 3 aid stations. The longest run I can recall doing without carrying anything was a 93-mile solo run.”

Race Across Tennessee

During the summer of 1983, Gary put on a race across Tennessee, something he had always wanted to do. “Cantrell levied a toll of 25 cents for the 122-miler, generating an income of $2.25 from entry fees. He called it a ‘two-bit race,’ saying ‘By two-bit standards, the course is a piece of cake.” Three finished. The race was repeated in 1984 and was a predecessor of the Last Annual Vol-State 500K Endurance Run that would be created in 2006.

Gary loved being out on the open roads of Tennessee. He wrote, “I live in one of the loveliest places in the country. Shady gravel roads crisscross the rolling green hills, providing inspiration for my running.” He ran some new roads at the end of the year, and said, “Growing my running map became a passion. I left on Christmas eve and ran overnight to Sandra’s dad’s house in Dickson for Christmas. It was a hundred and some odd miles, depending on which way you went. I eventually went to all of them, and part of the holiday tradition became reports on where family members passed me on their way to the gatherings. When I arrived, it was a nice hot shower, a huge feast, and I spent the rest of the day either watching ball games or sitting on the back porch drinking beer and smoking cigarettes.”

He did many other journey runs. “I took trips that went on for days, overnighting in cheap motels, or cemeteries and church lawns. My map grew and grew. Sandra took me to Arkansas and let me out. A week later, I showed up at home. (She loves to tell people that no matter where she dumps me, I always find my way home.) Somewhere along the way, my goal became to add every county in the state to my map. Of course, there are rules. All the lines had to connect. The map I have now is something to see. It is 30 feet long, and 5 feet tall. It is crisscrossed with lines.”

Many times, Gary treated a long run as a service activity. “Once, I noticed that someone’s milk cows had not been milked. It was afternoon. They were in pain, with severely swollen udders. I stopped at the next house up the road and told them what I had observed. It wasn’t their cows, but they went to check on the owner, an old man living alone. He was incapacitated and wouldn’t have received help any time soon had I not noticed that something was wrong. I have always gotten great rewards. No reward is better than knowing I helped someone out.”

Ultrarunning Magazine – From the South

Gary addressed qualifying standards for tough ultras. Half of his inquires for his Idiot’s Run “had no business attempting any sort of ultramarathon at all.” But he wasn’t in favor of speed requirements to limit the field size. Instead, Gary seemed to gravitate toward a short open-ended question on applications to have the runner explain why they were worthy to run the event. Clearly, these thoughts would later lead to his future Barkley essay requirement. To limit the size of an ultra, he endorsed the first-come-first-served method or using a lottery.

Gary encouraged other ultrarunners to not run the same mellow 10-mile training run day after day, rather to get out and explore. He encouraged runners to try to tackle long training runs like his attempts to run across Tennessee. Ever the poet, he wrote:

Barkley Ideas Emerge

Four years before the Barkley Marathons were created, in 1982, Gary wrote, “My own pet project is an attempt at the perimeter trail at Frozen Head State Park in east Tennessee. While it is only 26 miles, there is no possibility of any fluids or supplies except those carried by the runner, and the terrain is unimaginably difficult.” In 1983, he was writing on topics that later applied to his future Barkley race. He wrote about “the toughest course,” sharing the opinion that the toughest wouldn’t just involve steep elevation climbs, rocky terrains, and extreme distance, but would also involve a mental toughness aspect to it, introducing mental stress. He also wrote about the benefits and dangers of media coverage of ultras. It could bring an air of legitimacy to the sport, or create a story painting the race as a circus spectacle.

The question is often asked: How did Gary become Lazarus Lake? One explanation is that during the early Barkley years, when you finished a loop, you had to wake Gary up in his tent for him to register your time, like raising the biblical Lazarus from the dead. Another story is that while running in the 1980s, he found a phone book and noticed the unique name in it. He picked that nickname ten years later for his email address to protect his identity. There is some credibility around this story, because the only known person of that era named Lazarus Lake was a farmer and pastor in Bolivar, Tennessee, 160 miles away. Cantrell liked people to puzzle over things about him. He said, “Wrong information out there is OK. It just makes the truth harder to find.”

Gary loved the simplicity of the sport. “Our sport is one of the very few in which any man or woman has the opportunity to join, as a full member, an athletic community. There are no mediocre ultramarathoners, only great ones. We are seeking our limits, reaching for greatness, and living our lives to the fullest.”

Gary continued to compete in many ultras until about 1985, when he turned most of his efforts into directing races and creating the Barkley Marathons. He said, “If I had been the runner I had wanted to be, I would have never put on a race. My career would have been over decades ago. What seemed like bad luck at the time was really good luck. I was able to stay involved in the sport.” When he quit keeping a running log in the early 1990s, he had run 50 miles or further (including trainings run) more than 300 times.

As he looked back on the years and his induction in the American Ultrarunning Hall of Fame, Gary wrote: “All I have really done is to put on the races I would like to run the way I thought they should be put on. The reward was so great that I kept doing it even when I could no longer run them, and the rewards have been many: The places I have been, the people I have met, the great performances I have seen, the ones that amazed the world, and the ones that amazed only the athletes who did them.”