Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 28:13 — 32.1MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

![]()

![]()

Both a podcast episode and a full article

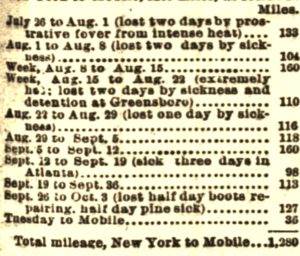

Women got into the game too! The most famous of the transcontinental woman walkers of the late 1800s, and perhaps the first, was a Spanish-American world-famous actress, Zoe Gayton. The may have also been the first person to walk the history transcontinental railroad end-to-end. Here is her amazing story of her walk in 1890-91.

Zorika Gaytoni Lopez Ares “Zoe Gayton,” was born in about 1854, in Madrid, Spain. When she was about four years old, her father became a political exiled immigrant and they came to New York City. Zoe Gayton started performing in the theater at the early age of 14 in Tennessee and then joined a company in New York City.

Zoe Gayton married at about 18 years old, to famous rich man, John H. Church, who was the owner of the Golden Gate Theater in Oakland, California. He had many wives, some at the same time. Zoe toured with him to South America. They lived in Utah for a time, building the first hotel in Little Cottonwood Canyon, Utah (location now of Alta and Snowbird ski resorts). They divorced in 1873 and Zoe then went through a series of other marriages as she continued to perform. She later joined companies in the west, performed in many places, and took a company to perform in Hawaii.

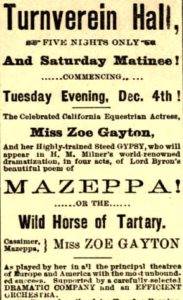

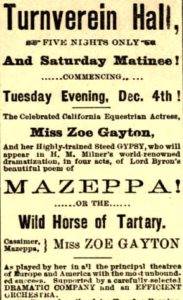

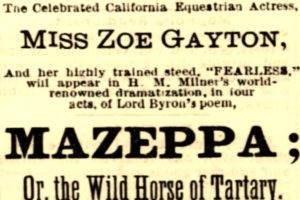

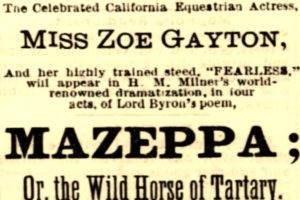

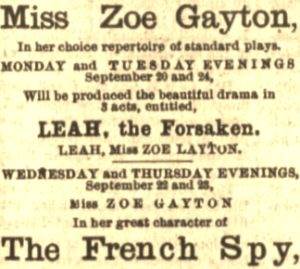

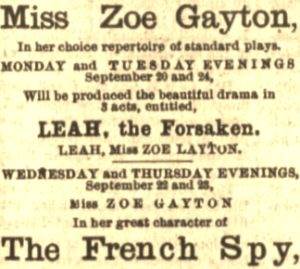

Mazeppa

In 1882 Zoe Gayton performed “Mazeppa” in England at Queen Victoria’s New Royal Theatre. As she was touring, Zoe was arrested for stealing things at a boarding house where she was staying with her manager William J. Marshall. She took ten table clothes, a silk-velvet cape, a shawl, an umbrella, a lace scarf, and other items. They were found in her possession, she was convicted and sentenced to four months in prison.

Zoe had performed all over the world including England, Scotland, France, Spain, Germany, Australia, India, Peru and all over America. But her years of success playing Mazeppa finally came crashing down. In 1885 her company was bankrupted performing in Kansas and her personal luggage was sold off to pay debts.

Plans for a Transcontinental Walk

During the summer of 1890, Zoe Gayton with others, were talking in a hotel dining room. George H. Clark, a well-known sporting man and a heavy gambler told the story about two young men who on a wager rode horseback from New York to San Francisco, averaging 15 miles per day. In half jest, Zoe said she could walk it in that time. Others disputed her bold claim and it evolved into a large wager by Clark.

Zoe later admitted, “I have always been lazy, and never walked a block if there was a cab or a car in sight. Yet I had made the statement and so I determined to stick to it to the letter. My friends tried to dissuade me, telling me that it would be the death of me.”

In 1890, Zoe Gayton, at age 36, shocked the theater world when she accepted a $2,000 wager, plus expenses, to accomplish a transcontinental walk from San Francisco to New York City in 226 days for an average of 15 miles per day. Her theatrical manager, William J. Marshall, would accompany and support her along the way. Joseph L Price also would go along as a witness for the wager and make sure she didn’t take any rides.

Zoe claimed that she had never accomplished long distance walking, but Marshall mentioned that she was already an accomplish pedestrian and yeas earlier in 1884 walked from Los Angeles to Deming, New Mexico, 600 miles in six weeks. Perhaps Zoe chose to keep that quiet for betting purposes.

Early Miles in California

Zoe Gayton, Marshall, and Price were accompanied by two dogs, Zoe’s “Beauty,” a cocker spaniel and “Lion,” a Gordon setter, a fine hunting dog. Near Lathrop, California, Marshall shot a duck. Lion went to fetch it, but when crossing a train trestle, coming back with the duck in his mouth, a train struck the dog. The next day he died.

Zoe’s trip was nearly stopped early near Stockton, California. She said, “I was caught on a railroad bridge and while there was plenty of room for the train to pass, I took my dog ‘Beauty’ in my arms and jumped into a marsh, a distance of fourteen feet. I was not hurt at all but was all covered in mud.”

Nevada to Colorado

When asked what they ate, Zoe replied, “We fished, and I tell you, mountain brook suckers are good when you are hungry and tired. We shot quail and jack rabbits.” Zoe even shot an antelope in the Sierra Nevada and didn’t know what to do with it. She said, “We got some good meat off it. But no vegetables, we went for sixteen days without even so much as a potato.”

Near Clark’s Station, Nevada they had a scare. Zoe recalled, ”We usually had all the apples, oranges and apricots we desired, but this time we were short in fruit. Mr. Marshall went to a certain orchard to procure some when he was discovered and the angry farmer shot him but fortunately, he was only slightly wounded. I always carried my rifle and revolver while out west.”

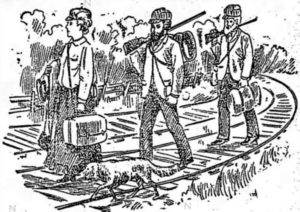

As for their supplies at first, they packed tea, sugar, bacon, butter, two blankets, one knife and one fork. They bought bread along the way. Zoe said, “Lots of people took us for tramps (railroad hobos) and wouldn’t give or sell us food. I had offered as high as $1 for a loaf of bread and didn’t get it.” They later carried four changes of linens and left some behind to get laundered and then mailed ahead.

They had difficulty at times finding water in the desert and each of them had to carry a canteen. After leaving Battle Mountain, Nevada, there were no house seen for three days and they went without food. They only carried small hand satchels.

Their trip over both the Sierra and the Rocky mountains was difficult and they had to carry a heavy outfit through the west. At times they used stray railroad ties to construct shelters to get out of the wind and the storms.

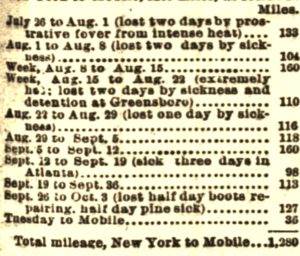

Curiously, there was no news coverage found for about 1,000 miles through Utah, Wyoming, and western Nebraska. It is very odd that the newspapers in Utah didn’t cover their journey since Zoe once lived there. Wyoming was the most remote section and they would have had to received help from the railroad way stations. However, analyzing their miles and days, it all seemed to fit into a realistic pace.

Nebraska

Zoe made sure she stayed ahead of the 15-mile-per-day average. Up to this point, she was being successful walking 20 miles average per day. Her biggest day had been 34 miles. She didn’t walk every day. They were delayed by storms and took days off, requiring her to do bigger mileage days.

Not everyone considered her attempt as heroic. One newspaper in Kansas wrote, “The craze for notoriety still pervades this country. Those who are thirsting for it seem willing to resort to anything to obtain it. And there are as many women as men in the throng.” A paper in Delaware speculated that after she completed her walk that she would be hired as a “pedestrian freak” for some dime museum.

Illinois

On January 6, 1891, Zoe and her crew arrived at Davenport, Iowa, and the next day crossed the Mississippi River into Illinois. One observer said, “They are an unpretentious three and make it a point to stop a private boarding houses where they attract little attention.” It is curious that someone such as her, who was used to a lot of attention and was seeking for more, would avoid attention during her walk. She said, “In some places there were large crowds at the stations to see me, and when I could not dodge them, I had to pass through the ordeal of answering a thousand questions and shaking hands with hundreds.”

Thus far she had only left the train tracks a few times. For one week she did it to avoid the crowds at small towns. “If it is known that she is coming, crowds of several hundred hoodlums gather around to see her coming in, which is very annoying to her.” The most miles she put in during a given week was 187 miles.

Chicago

On January 14, 1891, Zoe Gayton arrived at Chicago, twenty days ahead of schedule, and she stayed at the Waverly Hotel. She had gone through several pair of shoes and said, “I had walking shoes made for me and they blistered my feet so that since then I have worn nothing but common pebble-goat shoes half-soled.” Her preferred shoes were high laced, two sizes larger than usual, with studded nails in the soles.

Media attention became more intense and because of all of her railroad traveling, they called her, “The Queen of Ties.” She spent ten days in Chicago and had about 1,000 miles to go as she plodded along on the Michigan Central Railway.

Michigan

On February 6, 1891, Zoe Gayton arrived in Detroit. Reporters gathered at the place she was staying. She explained that she was getting tired. “At first I was very eager for morning so that I could get started, but I am getting over that now. You have no doubt seen men driving cattle along some road and noticed how weary the poor animals looked. Well, I feel just as the cattle appear, just as if somebody were driving me with all their might.”

A Detroit newspaper dispelled the idea that she was a lovely woman in a short skirt tripping along over the railway ties and dodging express trains with a vigorous little shriek. “After allowing the effect of exposure to the weather, Zoe could not honestly be called good looking. Regarding danger, should a tramp molest Zoe, he would subsequently regret his boldness. Her good right arm could fell an ordinary man to the ground. No, the danger is delusion, as well as the beauty.”

Canada

When Zoe left Detroit, she crossed over the Detroit River by ferry, and entered, Windsor, Canada. She next walked on the Michigan Central Railway toward Buffalo, New York. Zoe and her company were starting to be called the “Sunset Special” by the railroad men who passed by them often.

On February 17, 1891, Zoe arrived at Bismarck, Ontario, Canada. The walking in Canada had been terrible. She had been away from San Francisco for 173 days and had walked 138 of those days.

New York

On February 25, 1891, Zoe Gayton crossed the International railroad bridge back into the U.S. and was met by a huge crowd on Niagara Street in Buffalo. The bridge operator said she was the first woman ever allowed to cross the bridge on foot. Once in Buffalo, “it was almost impossible to get along, owing to the numerous handshaking. A cab was finally hailed and the weary pedestrian was bandied in and driven to the Stafford house in Buffalo. It is presumed that she will start from the point where she took the cab.”

It was written of her, “She looks as brown as an Indian and strong as a young colt. She moved about with the agility of a cat.” She had walked 2,951 miles, in 184 days, including 148 walking days. Thirty-seven days had been lost because of bad weather. Her best week was between Chicago and Detroit when she walked 195 miles on a very good road.

Marshall went ahead to make arrangements for their stay in Rochester, New York. He was described as a gray-haired but hardy looking man. He expressed that he was very appreciative toward the railroad companies,“Men have been very kind to us along the route and have shown much interest in the trip. Nearly all the employees of the different divisions were kept informed of our whereabouts and often as the through trains passed us on the plains, where we were the only human beings in sight of the passengers for hours, handkerchiefs would be waved at us and frequently flowers and other presents thrown from the train.”

Her last night was spent in Irvington, New York, with about 22 miles left. It was reported, “As soon as she reached the hotel, she sank down into a chair. The tears sprang to her eyes, and she lay back in her chair completely worn out. She felt better, however after she had partaken heartily of supper. Shortly after supper she retired to her room.”

The Finish

Banners were hung in her honor. An open horse-drawn carriage took her to the Police Gazette newspaper office where a reception was held. She said that was the first time she took a ride in seven months, but she must have forgotten the ride she took to a hotel in Buffalo. It was reported, “When she reached her destination a more weather-stained weary looking woman was never seen. She was covered with dust from head to foot.”

Zoe went to stay at the Ashland House where all visitors were turned away. Doctors advised that she rest for two or three days. It was observed that her feet and limbs were swollen much larger than normal. It was believed that she was having a “nervous prostration” for the past few day and had not been able to sleep or eat. She was asked if she would ever do it again. She replied, “Not for the world. When I left San Francisco my hair had no gray hair in it. What you see there now are due to the strain I have been under, and I had all I could to keep from breaking down.”

When approached about these accusations, Zoe’s eyes filled with tears. She said, “I tell you candidly that this talk of my not having made the trip is maddening. The station agents and trainmen along the line can testify whether or not I made the trip. All I want is justice.” She challenged her accusers to “put up or shut up” and produced news articles from California that were published during the early stages of her walk.

Did Zoe Gayton really do it? With all the news stories left behind, the evidence seems to confirm the accomplishment. The largest gap in new stories was in Utah, Wyoming, and Nebraska where the population was very sparse along the railroad lines. Without taking rides on trains, they would have had to receive significant help from the Central Pacific and Union Pacific Railroads. The story of her accomplishment was published in just about every newspaper at the time and you would think that railroad employees would come forward to dispute the story, but they didn’t. Unlike Dakota Bob, Zoe Gayton’s stories on the road were full of believable details and were very consistent.

Fame From the Walk

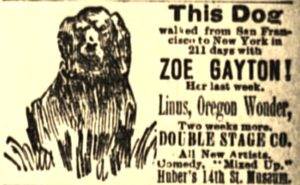

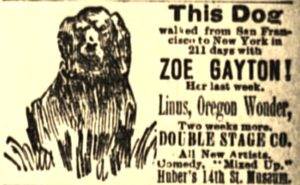

A strange newspaper article appeared in Illinois that stated that across the city of New York, posters were displayed “bearing the interesting information that Miss Zoe Gayton the pedestrian, and J. L. Price, one of her companions, would be married this week on the stage at Huber’s Museum.” The ceremony was supposed to be held on April 26, 1891 but the bride and groom didn’t show up and the crowd had to instead watch the performance of a snake charmer and a iron-jawed man.”

It was then rumored that actually Zoe Gayton and Price had already been married nearly a year earlier in Denver, well before her transcontinental walk began. This rumor put further suspicion on Price’s role as the transcontinental walk witness. Price disappeared for awhile. Gayton and Marshall were fired by the museum after the wedding didn’t happen. It is very possible that there really was no huge wager involved with Zoe Gayton’s transcontinental walk, that it was just a complex scheme for her to get attention and revive her acting career.

Zoe Gayton soon organized her own dramatic company, “Zoe Gayton & Co.” performing “Mazeppa” again. Price was her manager. Another incident cast great doubt on Zoe ‘s character. In February, 1892 at Columbus, Ohio, Price was hiring a treasurer for Zoe’s company and required a $25 deposit from the person he hired. It was discovered that he “hired” two men and was called a “fake.” The men went to the authorities and an arrest warrant was issued. Zoe’s property was to be take to compensate the men. It was reported, “When Constable Scurry attempted to serve the papers, Miss Gayton pulled a revolver and chased him from her apartment. Policeman Wolfel took the revolver away from her, and her trunk. Price was arrested by the police authorities.”

A few weeks later, Zoe opened in Minneapolis, Minnesota playing her old role of “Mazeppa.” Apparently, the company quickly failed. A month later Zoe joined a traveling novelty company that played at towns on the road and she was highlighted as the “transcontinental pedestrienne.” But that also quickly failed.

Copycats

Pretenders soon wanted to join the spotlight. Miss E. M. Jordan of Lynn, Massachusetts proclaimed that she could beat Zoe’s time in walking both to and from San Francisco and sought for a $10,000 sponsorship. J. Edwin Stone took up the challenge in 1892 and was averaging 24 miles a day. As Dakota Bob did, he obtained signatures in all the towns and stations he went through as proof. In 1893 Edward Lockwood and a young man started from San Francisco determined to break “Zoe Gayton’s record.”

1892 New York to San Francisco

She reached New Orleans in late October and put on a show racing Henry Klink, a champion short distance walker. She became sick and lost 23 days, but in November she was back on schedule in Galveston Texas. There, she helped a sick woman she found dying on the railroad tracks. Marshall and Price were taking turns being with her. The plan was for Price to walk with her to Houston, Texas where Marshall would take over, and Price would ride the train to El Paso, Texas.

Nothing more was found about this walk. Did she finish? It is doubtful because no news was found about her passing through cities. But a statement was found in later years that she claimed that she finished this second transcontinental walk. Given her health issues and no press coverage one must be skeptical.

Walk Around the World

Later in 1893 Zoe Gayton was scheduled to do another transcontinental walk starting on September 1st. But when that day came, she was said to be in Wetland, Ontario, Canada. In 1894 she claimed to be on a walk with Marshall from Albany, New York to Portland, Oregon where she planned to take a wager of $20,000 to walk around the world, averaging 26 miles per day. But by November she was on a walk from Grand Rapids, Michigan to Kansas City in 28 days for $500 which she claimed to complete. Her walk around the world was scheduled for December 15th but was delayed.

At Ellensburg, Washington Zoe was delayed getting her shoes fixed. Over the Cascade Mountains, in Yakima, Washington, the news commented that she appeared to be big and strong and Marshall looked really old and slow. The news predicted that he wouldn’t make it out of Washington. Zoe was walking about 26 miles per day.

A man, V. H. Sutton started out about July 1st from Seattle and vowed to overtake Zoe Gayton and do his own walk around the world. He lectured along the way and sold pictures. At about that time, Zoe passed through La Grande Oregon. She evidently made it as far as Green River, Utah but stopped “because of a hitch in the proceedings.” Sutton only made it to Portland, Oregon.

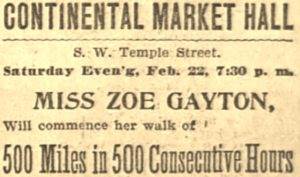

1896 500 Miles in 500 Consecutive Hours

Zoe’s first 50 miles went well despite catching a cold. Spectator attendance increased each day, especially among the ladies. She reached 250 miles on Mar 3rd. In the evenings other events were held such as five-mile races, tug-of-war contests, wheelbarrow races, wrestling, club swinging, and obstacle races.

After completing her 350th mile it was reported that Zoe was “becoming quite worn with the exertion and is not making as good time as formerly.” She quit at mile 356 when she developed an “acute attack of pleurisy” and a fever. Her excuses for not finishing included that the hall was not properly heated and “her quarters were wholly unsuitable, being only partially partitioned off from the big hall.” But her 356-mile accomplishment confirmed that she could walk 24 miles a day for a very long time.

Salt Lake City, Utah to Virginia City

Zoe Gayton’s Final Days

She married John Hall and was living in San Francisco with her father-in-law when the great earthquake of 1906 hit. She survived, but lost all her possessions including all her clothes

The legend of Zoe Gayton nearly totally disappeared in obscurity. But in 1941, a dramatized version of her story appeared on the radio show, Death Valley Days. In this version, Zoe was denied a Broadway role because she was an unknown. She declared that she would get there if she had to walk and wagered $2,000 with the producer. Zoe won the bet and skyrocketed to success on Broadway. Well, she never played on Broadway, but Zoe Gayton did walk to it.

Read the entire transcontinental series:

- 1855 Walk Across South America

- Dakota Bob – Transcontinental Walker

- Zoe Gayton – Woman Transcontinental Walker

- The Wheelbarrow Man – Lyman Potter

- Edward Payson Weston’s 1909 Walk Across America

Sources:

- Harpers Book of Facts

- The Tennessean, Oct 15,1860

- The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Dec 18, 1873

- The Hawaiian Gazette, Dec 31, 1879

- Liverpool Mercury, Nov 4, 1882

- Oakland Tribune, Oct 22, Nov 3,1883

- The Montgomery Advertiser, Nov 30, Dec 18, 1884

- The Leavenworth Standard (Kansas), May 15, 1885

- The Daily Commonwealth (Topeka, Kansas), May 28, 1885

- The Record-Union (Sacramento, California), Sep 3,8, Dec 17, 1890

- San Francisco Chronicle, Sep 29, 1890, 1 Aug 1892, May 9, 1896, Mar 10, 1907

- The Columbus Telegram, Dec 18, 1890

- Harper Sentinel (Harper, Kansas), Dec 19, 1890

- The San Francisco Examiner, Dec 20, 1890

- The Wichita Daily Eagle (Kansas), Dec 24, 1890

- The Salt Lake Herald (Utah), Mar 31, 1891, Feb 23, Mar 4,6,8,11, 1896

- The Rock Island Argus (Illinois), Jan 7 1891

- The Daily Times (Davenport, Iowa), Jan 8, 1891

- The Indianapolis News, Jan 13, 1891

- Chicago Tribune, Jan 15, 1891

- The Daily Courier (San Bernardino, California), Jan 18, 1891

- Detroit Free Press, Feb 5, 7-8, 1891

- The Atchison Daily Globe (Kansas), Feb 6, 1891

- Pittsburgh Dispatch, Feb 20, 1891

- The Olean Democrat (New York), Feb 26, 1891

- Buffalo Commercial (New York), Feb 26-27, Mar 2, 1891

- Buffalo Morning Express (New York), Mar 1, 1891

- Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, New York), Mar 2,7, 21 1891

- The Morning News (Wilmington, Deleware), Mar 2, 1891

- San Francisco Chronicle, Mar 22, 1891

- The Evening World (New York City), Mar 27,28, Apr 11, 1891

- The San Francisco Call, Mar 28,30, 1891

- The San Francisco Examiner, Mar 28, 31, 1891

- Pottsville Republican (Pennsyvania), Mar 28, 1891

- The Boston Globe, Mar 28, Apr 6, 1891

- The Sun (New York), Mar 28, 1891

- The Los Angeles Times, Apr 6, 1891

- The Topeka State Journal (Kansas) Apr 17, 1891

- The Rock Island Argus (Illinois), Apr 27, 1891

- The Merchants Journal (Topeka, Kansas), May 23, 1891

- Chicago Tribune, Jun 27, 1892

- Louis Post-Dispatch, Jul 30, 1892

- Daily State Ledger (Jackson, Mississippi), Sep 16, 1892

- The Times-Democrat (New Orleans), Oct 20, 1892

- Ottawa Daily Citizen (Canada) Aug 24, 1894

- Lawrence Daily Journal, Nov 1, 1894

- The Buffalo Enquirer, May 7, 1895

- The Salt Lake Tribune, Feb 25, 1896

- The Piqua Daily Call, Feb 11, 1892

- The Atlanta Constitution, Sep 14, 1892

- The Times (Shreveport, Louisiana), Oct 2, 1941