Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 33:42 — 38.2MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

![]()

![]()

Both a podcast episode and a full article

In recent years, some of the ultrarunners who have run across America performed it by pushing baby joggers to carry their stuff in a self-supported mode. Once when Phil Rosenstein was pushing his jogger during his transcontinental run, an alarmed passing motorist called the police, and reported that a crazy person was pushing his baby along a busy highway in a baby carriage. In the general public’s mind, it is just too crazy to imagine someone running across the country pulling or pushing a contraption.

In recent years, some of the ultrarunners who have run across America performed it by pushing baby joggers to carry their stuff in a self-supported mode. Once when Phil Rosenstein was pushing his jogger during his transcontinental run, an alarmed passing motorist called the police, and reported that a crazy person was pushing his baby along a busy highway in a baby carriage. In the general public’s mind, it is just too crazy to imagine someone running across the country pulling or pushing a contraption.

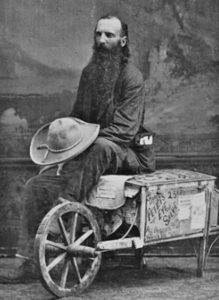

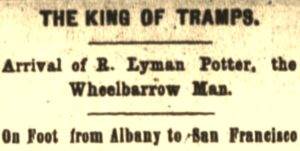

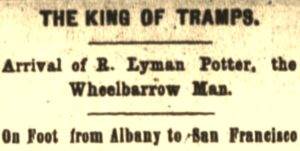

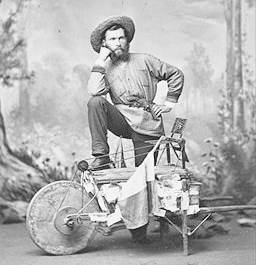

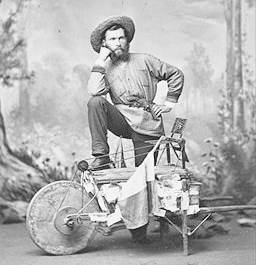

What about pushing a one-wheeled, wooden wheelbarrow across the country? That is exactly what Lyman Potter of Albany, New York did in 1878. He was one of the earliest known ultrawalkers to legitimately walk across America. He became known as “The Wheelbarrow Man.” The country was fascinated by him, but behind his back, he was called by many an idiot, a lunatic, and a fool. Why would anyone want to push a wheelbarrow across America, especially across the West when there were just rough wagon roads and a few railroads?

This is the story of “The Wheelbarrow Man” who would eventually be called “the hero of the greatest feat of pedestrianism.”

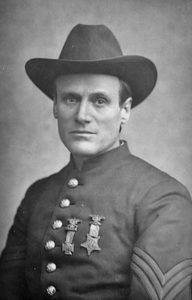

R. Lyman Potter

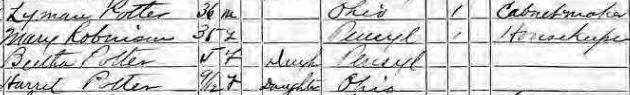

Richard “Lyman” Potter was born about 1840 in Marietta, Ohio. His father was an inventor, establishing patents. In 1862 the Potter family moved to Albany, New York. Lyman Potter then served as a private in the civil war. He returned to Albany where he worked with his father in patents and later as a plumber, an upholsterer, a cabinet maker, and a mattress maker.

In 1872 when President Ulysses Grant was reelected, Potter was so upset that he vowed he wouldn’t cut his hair or shave his face until a Democratic president was in the white house. His neighbors always thought he was very odd.

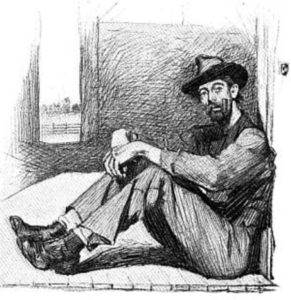

In 1875 at the age of 35, he was a widower. His wife likely died in childbirth the year before. He was left to raise two daughters, Bertha age four, and Harriet, an infant. They were cared by a live-in nanny/housekeeper, Mary Robinson. His furniture business soon experienced hard times so he did odd jobs in the city to support his family. He was a smaller man, about 5 foot 8 inches, 137 pounds, and wore a long straggling black beard and long hair. In early 1878, he was 37 years old, although looked older.

The Wheelbarrow Wager

In 1878 Potter and some friend were discussing the exploits of the famous Pedestrian, Daniel O’Leary. They started to banter about “this and that,” including whether any of them could walk for 100 consecutive hours. Potter said that was too easy, and before he knew it, a $1,000 wager resulted challenging Potter to push a wheelbarrow all the way from Albany, New York, to San Francisco, California. There were many individuals who put up money for the $1,000 purse which was deposited in a bank for Potter to collect if he was successful.

Potter explained, “It all came from too much talk. We was talkin’ about work and earnin’ money, and hard times, and I said I’d wheel a wheelbarrow to San Francisco for a dollar a day rather’n be without work. The Albany fellows took me up and made up $1,000. I had nothin’ to do and I wouldn’t back down.”

The terms for the wager required that he make it to San Francisco in 215 traveling days and in no more than 250 total days and must walk up to 4,085 miles during that time. He was not to travel on Sundays. Why was he doing truly doing it? He figured that he could make money, take many photographs, and write a book about his experiences along the way. A newspaper stated, “He is like the rest of mankind, ‘on the make,’ and is not doing all this wheelbarrowing for glory.”

The Start through New York

Potter rolled out from his home in Albany on April 10, 1878, at 3 p.m., in drenching rain with only $3.55 in his pocket. He needed to reach San Francisco by December 15th, taking off 35 Sundays. While it wouldn’t be a true transcontinental walk since he was starting in Albany, it was close, about 180 miles from New York City. During the early stages of his walk he was accompanied by Richard Downy who watched him, representing those involved with the $1,000 bet.

His first day’s journey to Schenectady, New York, of sixteen miles was horrible. He arrived footsore, wet, tired, and somewhat dispirited. It also rained the next day. He reached Utica, New York in six days after 125 miles and was tempted to quit. He might have done that if it hadn’t been for the negative tone in the newspapers. He said, “I intended to get through without making any stir or attracting any attention in the papers, but I had only got to Utica, New York when they began to talk and blow.” They ridiculed him, calling him an idiot, tramp, and a brainless fool, predicting that he would fail. After reading that, he was resolved to push on.

![]()

![]()

Potter sought room and board at nights in hotels in the towns and in farmhouses when in the open country, was treated kindly across New York, and rarely was allowed to pay for lodgings and meals. He claimed he wasn’t begging along the way but was willing and glad to accept a meal from anyone who saw fit to give it to him. He was budgeting ninety cents a day as he traveled. To make some money, he put advertisements on his wheelbarrow as he passed through towns and cities.

Ohio

The newspaper wrote, “Potter is an eccentric individual, both in appearance and speech. He would impress the stranger neither with his greatness nor with being remarkable in any particular. He walks with a sort of easy, shuffling gait, nor lifting his feet very high from the ground nor stepping very far at a time. He seems to enjoy the notoriety he is gaining. He wears thick boots, evidently cowhide.”

At Tiffin Ohio (about mile 700), much of the city folk were anxious for Potter to arrive. Someone pulled a prank and disguised himself with false hair and whiskers and pushed a wheelbarrow toward town a few hours before the true Potter arrived. Businessmen and everybody who could find the time swarmed around the bridge crossing over to the city. Sure enough, there was the Wheelbarrow Man, with a man on horseback following him. They came in at a “rattling pace” and passed through a cheering crowd.

The real Potter arrived at Tiffin a few hours later in cold and rainy weather. He was in good spirits but suffering from exposure. Once the people figured out that they had been tricked, they came back out by foot or horse carriage to cheer him into their city.

Since leaving Albany he had been averaging 26 miles per day. He needed to walk about 19 miles per day on his walking days and he believed that he was about seven days ahead of schedule. When he reached Toledo, Ohio he stayed over for Sunday. It bothered him that he was being called a “lunatic,” “king of tramps,” and “drunken bummer” in newspaper articles. Leaving Toledo, he was “accompanied by a large and enthusiastic crowd of small boys.”

Indiana

Potter had a book full of autographs of the people he met in every town, village, and farmhouse. An example entry read, “I saw Mr. R. Lyman Potter at Monroeville, Ohio. I left town about five or eight minutes after Mr. Potter started and trotted on my horse one and a half miles before I overtook him. I rode aside him for four and a half miles and found it quite difficult to keep up with him without trotting. I have a fast-walking mare. Mr. Potter is a very sociable man and seems to be a very good man.”

Potter picked up his mail at the Fort Wayne post office and then went back to the train depot followed by a large crowd, consisting mostly of boys, and then went to a house for the night. The next morning a big crowd saw him off. He said that his appetite was good and he appreciated those who took him in and fed him meals. He said of his long hair, “If the Indians scalp me, they won’t be disappointed, but will get a handful of hair.” About 300 people watched him leave town heading toward Chicago.

Greeted by a large crowd, Potter trundled into Plymouth, Indiana on May 20th. He was about six days ahead of scheduled, still averaging about 26 miles per day. It was reported, “He is dressed in a suit of butternut brown, and wears a broad brimmed, white wool hat. He walks easily and rapidly.” A crowd and a brass band led him into the town playing, “See the Conquering Hero Comes.”

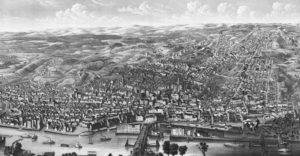

Illinois

![]()

![]()

The Chicago paper noted, “Nobody goes with him to see that he doesn’t cheat, for it would be no use. The farmers know of him all along the way, and he could not ride without being detected. Newspaper men watch him pretty close too.” He left the city pushing his load on the Chicago-Rock Island & Pacific Railroad.

Newspapers didn’t hold back on how stupid they thought this journey was. One stated, “Another lunatic is abroad, he has engaged to drive a wheelbarrow from Albany, New York, To San Francisco, Cal.” The news reached London and they worried what would happen if Potter ran into Indian chief Sitting Bull along the way.

On June 4th, Potter reached Geneseo, Illinois and continued on to Rock Island at the Mississippi River. It was reported, “He looks seedy and travel worn on the way, but when cleaned up presents not a very unpresentable appearance. He has the look of a tired man, though he says he is determined to win, and eats his meals with utmost regularity and relish.” He stopped off at a brewery and loved the beer. Crowds followed him to planned visits to bars and he received a share of the profits. He also made money by accepting letters to be delivered to California for 25 cents each. As he earned money he sent some of it home to support his children. He paid for his first hotel room on his trip in Rock Island.

Iowa

Nebraska

At Plum Creek, Nebraska he needed to stop for a few days because he had suffered from sunstroke. He wrote from Central City, “Plenty of wolves, snakes and everything that kills and murders.”

Near Idaho City, Nebraska, Potter said he ran into some railroad tramps (hobos). “They demanded tobacco and he gave them half his store of the weed. Then they wanted whisky and when he told them that all the whisky he had with him he used to bathe his shins, when walking caused them to swell, they knocked him down and reviled him. He drew a pistol (of which he carries several) and frightened them off. Thus was the whisky saved for legitimated use.”

At North Platte, Nebraska on July 14th (day 96), Potter reported that the weather was very hot but he was in good health. Near Ogalla, Nebraska, a frontiersman named Ash Hollow Bill used Potter’s wheelbarrow for target practice and smashed one of the springs with a rifle ball. After a good 40-mile day, near Sidney, Nebraska it was reported that he was frequently chased by cattle, and that might have been why he had such a high mileage day.

Wyoming

Utah

Potter arrived at Ogden, Utah on September 3rd (day 140) and stayed at the Union Depot Hotel. The people of Utah were not very impressed with his effort compared to the Mormon Pioneer treks a couple decades earlier in harsh conditions. “His trip is nothing to be compared with the journey of Mormon women with hand-carts across the Great American Desert, before there was any railroad to mark the path and when there were no houses or stations to rest at and recruit by the way.”

Nevada

Sergeant Gilbert H. Bates was a civil war veteran who created quite a stir when he walked the length of England carrying the stars and stripes on a pole in 1872. He returned to the United States and continued his walks through the Southern states at times expressing extreme political views. Most communities considered him a nuisance and many compared Potter to him.

Potter arrived in Elko, Nevada on September 16th, about 30 days ahead of schedule. The newspaper called him a “damn fool” and wrote, “If he makes the trip through to San Francisco successfully we propose that he be engaged to wheel Sergeant Bates over Yosemite Falls.”

Near Hanging Rock, Nevada, someone threw Potter a bottle of beer from a passenger train. Very thirsty, he drank the entire bottle. Within a mile he was seized with violent pains in his stomach and knew that he had been poisoned. He ate butter and drank saltwater that caused him to vomit out the poison but he was still sick and had to stop for several days. “He ascribes these persecutions to the agency of some individuals who have bets pending and desired his failure.”

Potter reached Winnemucca, Nevada on September 18th and he stayed at the Central Pacific Hotel. He joined in with the “boys” at the local saloon and bought drinks for them for a half dollar. The local paper wrote, “Unless he succumbs to the influence of whisky, he will accomplish his task with ease.” He had added some antelope horns to decorate his wheelbarrow.

Between Wadsworth and Reno, Nevada, Potter camped out one night with his timekeeper. “They found some railroad ties and threw up a little enclosure about breast high, and in the night were fired upon by some fellows who ran off in the darkness. A ball cut Potter’s coat-sleeve.” Potter returned fire with his six-shooter and thought that the men may had been wounded.

California

Crossing over the Sierra Nevada was difficult because of all the trestles to cross. “He trundled his barrow over bare trestles six and eight miles in extent, guiding the wheel along the inner foot of the rail, walking himself on the ties, and approaching trains seeing him in these positions invariably slacked up to give him time to get across. He passed through the forty miles of snow sheds across the Sierras without molestation, camping one or two nights in the sheds. His barrow is supplied with springs, the jolting over the ties doesn’t bother him much.”

On about October 5th (day 179) Potter arrived at Sacramento, California followed by a crowd of several hundred men and boys to the City Hotel. He was interviewed by a newspaper and mentioned that along the way he needed to stop several times to have his wheelbarrow repaired, “as the jolting threatened to knock it to pieces.” He said he did not get footsore but was tired of the job and wished it was over.

He continued to Oakland walking on the railway and then walked another railway to San Jose where he arrived on October, 18th (day 192). He went on to the suburbs of San Francisco and stopped for about a week.

The Finish

The press called him, “the hero of the greatest feat of pedestrianism, and notorious as the Wheelbarrow Man.” He came into the city by a police escort and led by a band to the Gardens where an eager crowd of up to 15,000 people were gathered, wanting to get a glimpse of him. An Oakland paper mocked, “he now is in common with the other monkeys, on exhibition at Woodward’s Gardens.” Potter received a salary to appear at the Gardens and would earn $250.

His witness who saw him at least once per day declared that Potter covered the entire way on foot, that he was not a fraud. A newspaper reporter stated, “I have examined his diary and studied his four books of autographs gathered along the road attesting his presence at the points indicated at the given date.” It was estimated that he had walked 3,995 miles in 201 days, averaging about 26 miles per walking day. Besides stopping Sundays, he stopped for an additional 20 days. Potter won the $1,000 wager.

Potter went through only five pair of heavy shoes. He wore them as long as possible because it was always a problem breaking in new shoes. “At times, he said, his feet were literally raw, and he was obliged to lay up several times on this account.”

On November 5th, Anton Bechler won a lawsuit against Potter to recover his salary and expenses going with him from Omaha. Potter didn’t show up at the court and Bechler was awarded $294.50. Potter’s salary at Woodward’s Garden covered $200 due to Bechler.

At Woodward’s Gardens, Potter walked every day from 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. in front of large crowds to add 90 miles to reach the required 4,085 miles. He officially finished on November 8th (day 213).

A poet, Samuel Booth, from California, wrote a poem honoring Booth that contained:

He started from Albany seven months ago.

And trundled a Wheelbarrow steady and slow,

In storm and in sunshine, through dust, wind and rain,

For thousand odd miles trudged the Wheelbarrow Man.

He traveled through cities and villages fair,

And long, dreary marches, where houses were rare;

Crossed creeks and deep canyon, where swift torrents ran

That almost rolled over the Wheelbarrow Man

He was chased by wild cattle while crossing the plains,

By poison and sickness bore infinite pains;

Was shot at by ruffians and put under ban,

But nothing could kill the bold Wheelbarrow Man

And so through all perils and dangers he passed,

Arriving in Frisco, in safety at last,

Where thousands of people were waiting to scan,

And welcome the wonderful Wheelbarrow Man

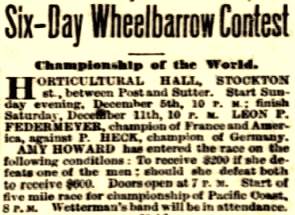

The Wheelbarrow Transcontinental Race

Potter intended to wheel back to Albany. Leon Pierre Federmeyer of Paris, France challenged him to a wheelbarrow race from San Francisco to New York for $1,500. Potter accepted and was sponsored by Pacific Life. Now famous, he planned to sell pictures of himself along the way. They both were required to get post office seals from every town that they went through and their wheelbarrow plus cargo had to weigh at least 130 pounds.

It seemed crazy to do this trek in the winter. One paper wrote, “If the Indians don’t get in their work in this trip, he stands a good chance of wheeling himself into a snowbank.”

The two started on December 8, 1878. They agreed to stay fairly close to each other until Cheyenne, Wyoming for safety. Federmeyer’s wheelbarrow was somewhat damaged when he was blown off a high railroad trestle in the mountains. In the Sierra they survived mostly on bread and crackers and some days went without food. Storms would delay them for many days and they confronted snow as high as two feet. Federmeyer suffered from frozen feet. Temperatures reached sixteen below zero.

The Two Part Ways

Potter wasn’t in any hurry to win the race. His main objective seemed to be making money. He arrived in Denver on April 8th, but took a huge detour to the mining town of Leadville, Colorado, to perform in a variety show for several weeks. On the way, he found a black teamster who had been run over by a wagon and was severely injured. Potter put him in his wheelbarrow and wheeled him 100 miles to Leadville where he recovered.

One day Potter wheeled his barrow 50 miles in twelve hours, in the brand new Tabor Opera House in Leadville. Later he performed at an exhibition in Denver, racing against pedestrian Johnny Oddy for three nights.

After four months, in April, Federmeyer reached Topeka, Kansas, about 650 miles ahead of Potter who was still in Leadville. The furthest Federmeyer walked in a day was 42 miles and usually traveled at 40-minute-mile pace. Crowds greeted both of them along the way and thought they were crazy. Near Ellis Kansas, Federmeyer, while crossing a bridge, fell off together with his wheelbarrow about fifteen feet to the ground. He was stunned, bruised and didn’t move for some time. He barely missed two huge stones that would have killed him. He still was able to continue the next day.

Potter finally left Denver and continued his journey east on May 16th but had decided to finish “at his leisure.” In Kansas, Potter ran his wheelbarrow off an embankment 20 feet and busted it up badly.

After six months, in June, Federmeyer was in Ohio with more than a 700 mile lead. On June 28th, Potter finally arrived in Lawrence Kansas. While in Kansas he had dodged some tornadoes. There were rumors in Kansas that Federmeyer has cheated 40 miles, taking rides on the railroad. Potter was collecting all sorts of things as he ambled on including a live young wolf (probably a coyote) he found in Kansas, and a couple squirrels.

Federmeyer Reaches New York First

After nearly eight months, Federmeyer arrived in New York on July 24, 1879 pushing his “quaint looking wheelbarrow marked ‘From San Francisco to New York.’” He signed an affidavit that he walked the entire distance. Potter was more than 1,000 miles behind, in Centralia, Illinois. Federmeyer made his long journey in seven months, sixteeen days.

An article joked, “The wheelbarrow is a great institution. The young men of the period have largely abandoned it as a highly unfashionable article of furniture. This race may lead to something useful. We may even find hoeing matches introduced among our field sports. Potato digging may yet take the place of polo.”

Potter really slowed down to a crawl and created a traveling show entertaining, displaying his wheelbarrow and the items he brought back with him. It was said he had 1,600 curiosities. “All who have seen it have been highly pleased.” Among his curiosities were tarantulas, centipedes, scorpions, white rattlesnakes, Indian relics, horned toads, a prairie dog, and his live wolf. His load now weighed more than 200 pounds. His wheelbarrow was in very rough shape. The wheel was tied and wedged to keep it from going into pieces. “It looks like a ball of rope bound with an iron hoop.” He no longer was bothered when anyone called him crazy because he knew he was a fool.

In August, 1879, Potter was in St. Louis, Missouri and slowly spent all of the next two years inching toward New York, sometimes spending several months around the same city. In November 1879, he was in Indiana. That month the wheelbarrow craze had spread to England. Robert Carlisle was pushing a wheelbarrow the length of Great Britain from Land’s End to John o’Groats.

in January, 1880, Potter reached Cincinnati, Ohio. During the summer he put on exhibitions near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. He spent the winter of 1880-81 in Baltimore, Maryland.

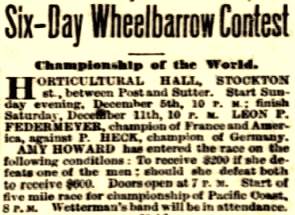

Six-Day Wheelbarrow Race

Heck used a crazy pushing method at times. “Without a moment’s warning, he would jerk the machine along at arm’s length and rush after it at a tremendous pace in the vain endeavor to catch up with the front wheel.” Amy Howard would very frequently change her dresses as if she were in a fashion show. As the first day was concluding, Heck found a new method and tied the back legs of the barrow to his arms. Both men were shuffling and Federmeyer was cramping. After 24 hours, Amy Howard was in the lead with 78 miles, followed by Heck with 75, and Federmeyer with 62. On day three, Federmeyer’s brought out a new wheelbarrow, 30 pounds lighter because his old trusty one had finally broken up. He was 10 miles ahead of Amy Howard and Heck was further behind struggling with a sore foot.

Three days later, the newspaper proudly reported, “The six-day wheelbarrow race, which was about as much a race as the fabled one of the tortoise and the crab closed last night. The blackboard marked the bearded Federmeyer 310 miles, Heck 230, and Miss Howard 254. The lady is therefore entitled to $200.” After that Federmeyer took up making portraits and landscapes from human hair and became known as “the wizard of human hair.” He died in 1913 in Illinois.

A Sad Wheelbarrow Man

During May, 1881, in Washington, D.C., a reporter recognized 41-year-old Potter walking on a street in the capital city. He was described as “a gaunt-looking man with long unkempt hair and beard on a care-worn face. His hollow eyes were shaded by the wide brim of a weather-stained slouch hat, his coat was a sort of ragged buckskin tunic.” The man asked, “Are you the wheelbarrow man?” Potter replied, “Yes, are you a reporter?” A curious crowd collected making it impossible to interview him. so Potter invited the man to the place he was staying. He first introduced the man to his wolf. Potter said, “I can do anything with him. I got him near Fort Wallace, Kansas.”

Potter took the man out to a shed. He focused the rays of light from a candle to a corner bringing into view an old worn wheelbarrow. On it was packed many boxes, bundles, blankets, a frying pan and other things. “The wheelbarrow looked as though it would not stand another ten miles of travel. The whole establishment looks like its owner, about all worn out. He had a large number of curiosities, including snakes and specimens picked up along the road, and several books filled with signatures and seals.”

Potter said, “I have walked fifteen thousand miles.” The reporter asked about his plans. “Well, I am going to Europe, and I thought I ought to come to the capital of my own country first.” He expressed disdain for how he was being treated in the East. “Out West I never had to pay a hotel bill or a whisky bill. Then in the East I wanted to get a permit to show my curiosities and I was refused. Since I am here, I might go over to Virginia.”

Potter explained why he had not returned to Albany to see his children for three years. “If I get there with my children, I won’t be able to get away.” He thought he could collect more curiosities in Europe to start a museum. The reporter said, “You’ve seen pretty hard times, I guess.” Potter replied, “Well, I have had fights with bears and mountain lions, and been run over by wild cattle, and handled pretty roughly. I camped outside of Baltimore with a gypsy.” As the reporter was about to leave, Potter put in his hand a copy of the poem, “Song of the Wheelbarrow Man” that Samuel Booth of San Francisco wrote about him.

Potter was in Virginia a couple months later displaying his museum of curiosities that included a rock collection from the Rocky Mountains. In December, 1881 he was near Richmond, Virginia. His shoe soles had worn down to “about a thousandth part of an inch.”

In early 1882, Potter likely returned home to Albany, New York, passing through New York City and finally finishing the west-to-east race after more than three years. At Albany he finally returned after being away for four years and may have remarried. His daughters were age twelve and seven.

New York to New Orleans

At some point late in 1882, contrary to his family and friend’s wishes, Potter left his Albany home and started another long wheelbarrow trip to New Orleans. Wagers were made and he was to arrive in New Orleans by a certain day. But after two months, his progress was so slow that his backers hedged their bets and he was left on his own. “He soon degenerated into a penniless tramp.” After he reached Tennessee, he decided to head back home.

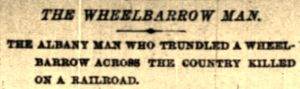

About six months after his start, in North Carolina, near Salisbury, a train engineer noticed in the glare of the headlights of his train, a glimpse of the figure of a white man lying dead by the track. The train stopped, backed up and train hands picked up the body and put it in the baggage car. The man was dressed in a suit of buckskin clothes and was at once recognized as Lyman Potter. His head had been crushed in, but no other marks were found on his body. He didn’t appear to be robbed and It was supposed that he had been standing near the tracks and was sideswiped by a passing freight train. He had last been seen in Salisbury with his wheelbarrow of curiosities along with his pet wolf. The large wolf was found and was very tame. It would eat out of a person’s hand and loved to be petted like a cat.

Farewell Wheelbarrow Man

“He had also a tame wolf, which it is said had been taught to sing and perform various funny and surprising tricks. Altogether the ‘Wheelbarrow Man’ was a remarkable subject, not for any good he was doing for himself or his family or any one else, but for his singularity. Letters were found among his things from his family begging him to come home, and telling of dear ones who could not hold out if he delayed.

Lyman Potter was only 42 years old when he was killed. The news of his death was covered in newspapers all over the country. Most of them were kind and some of them were rude, glad that he was gone. Potter was buried in Salisbury, North Carolina on April 4, 1883.

Potter’s wife of a few months didn’t seem too upset by his passing. She was hoping to sell the wheelbarrow for $1,000 and said she probably would sell the wolf to a menagerie. Yes, the wheelbarrow survived its owner. It was eventually sold to James Martin of New Jersey.

Before Potter was killed, he had left a box 17 x 10 x 9 inches with a drugstore owner, W. L. Cullum in Greensboro, North Carolina. Potter didn’t have enough room for it in his wheelbarrow and left it behind. He would let Cullum know where to ship it. He never did. Five years later, in 1887, Cullam finally decided to open the box and let others see what it contained. Inside was a lot of confederate money and bonds along with many other objects. “It was the most conglomerate exhibition we ever beheld.”

Ultra-Wheelbarrowing did not die with Lyman Potter. Others didn’t forget him and followed in his footsteps. In 1892, Hassen Mahomet, from Turkey, started a 450-day trek of 10,000 miles, pushing a wheelbarrow, visiting all the states and territories in the U.S. The wage involved $10,000 and he was restricted from begging. He needed to earn his way along the way by working, usually giving exhibitions. One other crazy condition, he had to return with a wife. Thus in many cities he had many willing proposals. It is unknown if he finished and found a wife.

Hopefully with this article, the legend of The Wheelbarrow Man will live on. I think is is appropriate for ultrarunning race directors of today to start adding wheelbarrow divisions to their races in honor of Lyman Potter. OK, maybe not. Runners using pull carts have finished my Pony Express Trail 100.

Read the entire transcontinental series:

- 1855 Walk Across South America

- Dakota Bob – Transcontinental Walker

- Zoe Gayton – Woman Transcontinental Walker

- The Wheelbarrow Man – Lyman Potter

- Edward Payson Weston’s 1909 Walk Across America

Sources:

- The Buffalo Commercial (Buffalo, New York), Apr 26, 1878

- Burlington Free Press (Vermont), May 14, 1878

- The Fort Wayne Sentinel, May 15,17, Jul 8,18, Aug 15, 1878,

- The Weekly Republican (Plymouth, Indiana), May 23, 1878.

- The Burlington Hawk-Eye (Burlington, Iowa), May 23, 1878

- The Inter Ocean (Chicago, Illinois), May 24, 1878

- The Daily Tribune (Lawrence, Kansas), May 25, 1878

- Racine Journal (Wisconsin), May 29, 1878

- Shelbina Democrat (Missouri), May 29, 1878

- The Tiffin Tribune (Ohio), May 30, Aug 22, 1878

- Detroit Free Press, Jun 1, Jul 23, 1878, Aug 11, Oct 20, 1878

- Quad-City Times (Davenport, Iowa) Jun 4,5,11, Jul 24, 1878

- The Belvidere Standard (Belvidere Illinois), Jun 4, 1878

- The Des Moines Register (Iowa), June 15, 1878

- Iowa State Leader, Jun 15, 1878

- The Black Hills Daily Times (Deadwood, South Dakota), Aug 1, 1878

- Oakland Tribune (California), Aug 5, 1878

- El Dorado Republican (Kansas), August 14, 1878

- Deseret News (Salt Lake City, Utah), Sep 4, Nov 6, 1878

- Silver State (Winnemucca, Nevada), Sep 19, 1878

- Reno Gazette-Journal (Nevada), Sep 27, Nov 12, Dec 26, 1878

- Nevada State Journal, Sep 28, 1878

- San Francisco Examiner, Sep 30, Oct 15,25, Nov 7-8,1878, Dec 4-12, 1880, Jul 5, 1892

- Boston Post, Oct 16, 1878

- Oakland Tribune, Oct 28, Nov 6, 1878

- Star Tribune (Minneapolis, Minnesota), Nov 6, 1878

- The Cincinnati Enquirer(Ohio), Nov 7, 1878

- The Buffalo Commercial (New York),, Dec 23, 1878

- Yerington Times (Nevada), Dec 25, 1878

- The Daily Ogden Junction (Utah), Mar 1, 1879

- The Times (Philadelphia), Jul 19, 1878, Mar 10, 1879

- Pottawatomie Chief (St. Marys, Kansas), Apr 12, 1879

- Arizona Weekly Citizen (Tucson), Jul 5, 1878

- Pittsburgh Daily Post, Jun 18, 1879, Jul 7, 1880

- The Kansas Daily Tribune (Lawrence, Kansas), Jun 28, 1879

- The Junction City Weekly Union (Kansas), Jun 28, 1879

- Buffalo Weekly Courier (New York), Jul 30, 1879

- The Cincinnati Daily Star, Aug 13, 1878, Jan 17, 1880

- The Wheeling Daily Intelligencer (West Virginia), Jun 17, 1880

- The Tennessean, Sep 5, 1880

- Oakland Tribune, Oct 2, 1880

- The Wilson Advance (North Carolina), Dec 17, 1880

- National Republican (Washington, D.C.), May 19 1881

- Shenandoah Herald (Woodstock, Virginia), Jul 27, 1881

- The Charlotte Democrat (North Carolina), Dec 2, 1881

- The Wilmington Morning Star (North Carolina), Apr 4, 1883

- The Chatham Record (North Carolina), Apr 5, 1883

- Carolina Watchman (Salisbury, North Carolina), Apr 5, 1883

- The Morning News, (Greensboro, North Carolina), Apr 13, 1887

- “The Wheelbarrow Man”