Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 31:27 — 35.8MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

![]()

![]()

Both a podcast episode and a full article

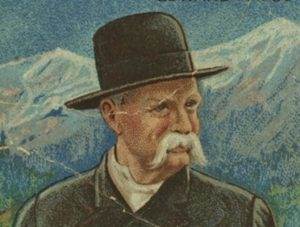

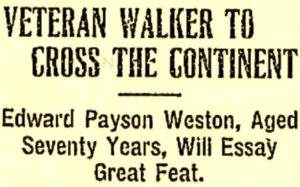

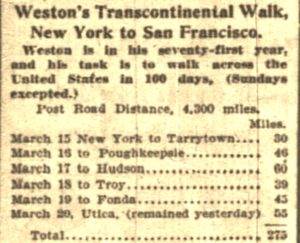

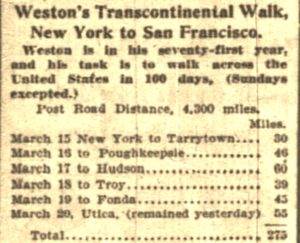

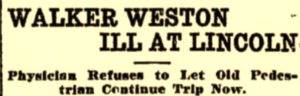

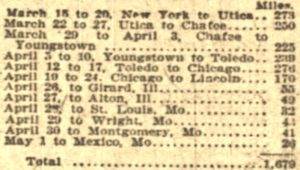

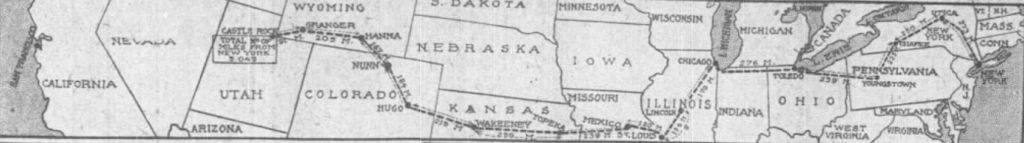

In previous articles, stories were shared about various walks across America in the 1800s. In 1909 Edward Payson Weston, the most famous American Pedestrian of the 1800’s made his transcontinental walking attempt in the twilight of his walking career, at the age of 70. His amazing walk captured the attention of the entire country and was the most famous transcontinental walk across America in history.

In previous articles, stories were shared about various walks across America in the 1800s. In 1909 Edward Payson Weston, the most famous American Pedestrian of the 1800’s made his transcontinental walking attempt in the twilight of his walking career, at the age of 70. His amazing walk captured the attention of the entire country and was the most famous transcontinental walk across America in history.

Edward Payson Weston (1839-1929) was born in Providence, Rhode Island on March 15, 1839. He was not particularly strong as a boy and took up walking to improve his health with exercise. When he was 22, on a bet, he walked from Boston to Washington to witness the inauguration of President Abraham Lincoln, covering 453 miles in about 208 hours. In 1867, he walked from Portland, Maine to Chicago, about 1,200 miles, in about 26 days. That walk brought him worldwide fame.

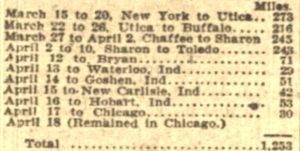

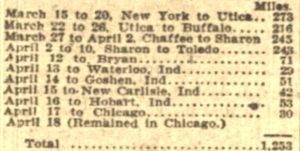

Over the next few decades, he was a professional walker and took part in many indoor multiday races. He gained more fame when he went and competed in England in 1876. Later in life, Weston gained intense attention in America in 1907 when at the age of 68, he again walked from Maine to Chicago and beat his 1867 time by more than a day.

Since 1869 Weston expressed a desire to walk across America. Many had claimed that they accomplished it. Finally, in 1909 he decided he would make his attempt starting on his 70th birthday.

Here is the story of his famous 1909 transcontinental walk.

Plans

In 1909 there weren’t any paved roads across the country, just some pavement in the cities. His route would be on dirt road “turnpikes” and on railroads. Along the way he wanted to deliver lectures, and give walking demonstrations, probably for money. Because of all the past fraudulent transcontinental walks by others, he wanted witnesses to keep him under surveillance to verify his accomplishment. It was recognized by the press, “Several alleged walks across the continent have been heralded from time to time, but their accuracy has been so vague as to be valueless for records of bona fide achievements.”

At first Weston planned to walk from New York to Seattle and then head south to San Francisco. For his past long point-to-point walks, he had used horse carriages as crew, but the horses would wear out. This time he made plans for an automobile to go along with him. He wanted his route to include bridges, with no ferries, so he could walk every foot of the way. He purposely wanted to boycott going through Cleveland because in 1907 he was treated poorly by city crowds and didn’t receive what he thought was proper protection for that walk.

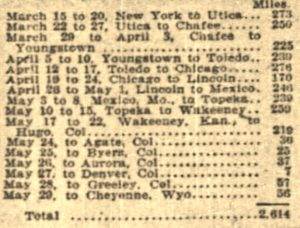

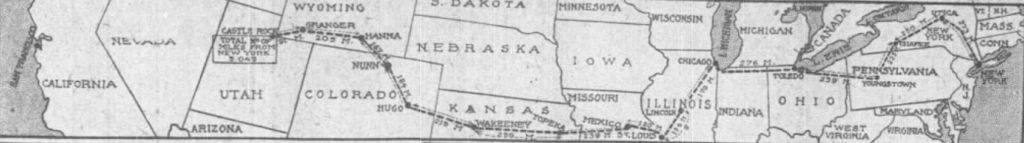

As the day approached Weston changed route plans. Instead of heading to Seattle, he planned to head to Los Angeles and then north to San Francisco. He planned send daily updates of his walk to the New York Times by telegraph. Those updates are the primary source for this article

The Start

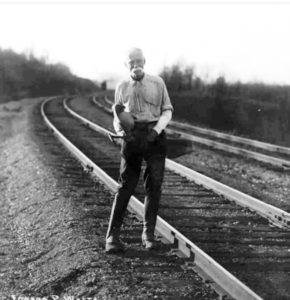

Weston started his transcontinental walk on his 70th birthday, on March 15, 1909, at the General Post Office in lower Manhattan, in New York City. He was late to arrive at his planned start time at 4:15 p.m. which worried many, but “suddenly the swinging doors were thrown wide open and Weston raced into the middle of the floor,” and briefly greeted friends. He later revealed that his left foot that had been injured ten weeks earlier, was in great pain, and that he was “frightened to death.” He didn’t stay long and quickly went down the steps of the building to the street. It was reported, “His walking costume was composed of a blue coat of light weight, riding trousers, mouse-colored leggings, and a felt hat of broad brim that resembled a sombrero in all but color.”

There was a large crowd around the Post Office that pressed closely around Weston as he started. He said, “I was praying every step I took that no one would ever have the chance to say, ‘I told you so.’”

“Walking with a springy step and general jaunty air” Weston started his journey. The large crowd yelled out repeated cheers and shouts of encouragement. Policemen escorted him for the first few miles on the city streets. Crowds followed after him as he walked through the streets of the city. At 59th Street and band played “Auld Lang Syne.”

New York

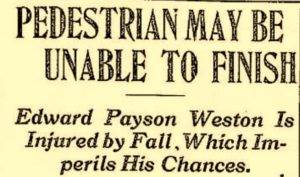

Some unkind people hoped Weston would fail. One article stated, “On the second day, Weston limped and the third day he fell over a pebble and skinned his face and had to rest a long time before he could go on and when he went on, he walked lame. What started out to be a triumph over years threatens to wind up in a pitiful display of its effects. Weston better had stayed at home.”

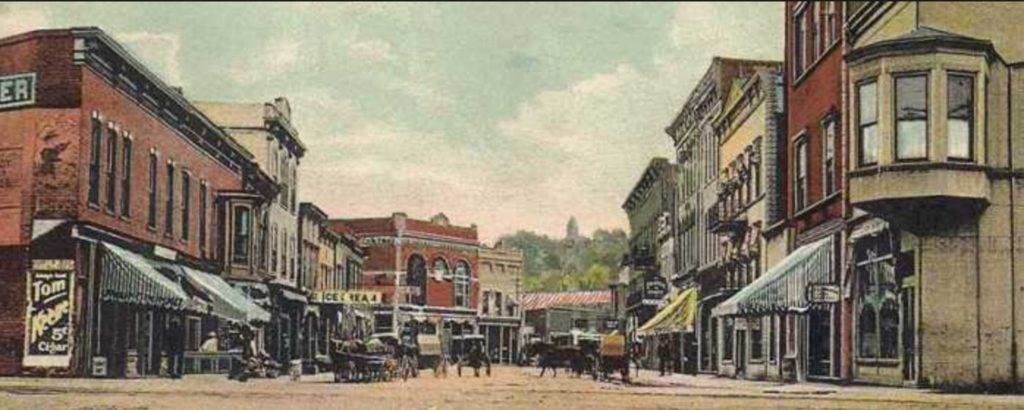

After resting his first Sunday at Utica, New York, he started walking again five minutes after midnight on Monday morning. Along the way he fought through headwinds and sticky red clay on the road. He said that his feet sank nearly to the ankle and “whenever I pulled out a boot it sounded like a cow’s hoof coming out of the mud.” He remarked that it was the most hazardous road section he had ever encountered, and he had to struggle through it for ten straight hours. At Syracuse, New York, he walked four miles through lines of thousands of enthusiastic spectators.

A description of his arrival included, “Soon was audible the chugging of a pair of automobiles moving slowly in the wake of a single, hurrying figure toward which all eyes were turned, tramping stolidly, stubbornly through the clinging mud. Soon the pedestrian had reached the pavement and with unflagging stride breasted the hill. A mighty cheer arose as the crowd disintegrated at his approach, deploying forward as an uproarlous bodyguard.”

Weston next walked on the tow path of the Erie Canal that contained awful frozen ruts that were a dangerous hazard, threatening to twist Weston’s ankles. People came out of the farmhouses along the way to cheer him. For the first time, rain fell on him and he put on an “oilcloth suit and fisherman’s hat.” Rain eventually changed to snow on his 11th day and he said, “I found the snow and slush more than a foot deep with wind and gale blowing directly in my teeth at the rate of fifty miles an hour.”

Weston tried to start early the next morning, but the blizzard was so bad that the automobile carrying his crew was blown into a show drift. He decided to return to the house he had stayed at to wait out the worst of the storm. When he eventually continued, he said, “every house I passed a good woman or man came out and offered me hot refreshments and any aid within their power to bestow.” He pushed on ahead through huge snow drifts that he had to crawl through on his hands and knees and the car struggled to keep up. The attending vehicle eventually became hopelessly stuck and Weston went along alone for 22 miles but received some help from some pedestrians who came out from Buffalo to escort him to the city.

When he arrived at Buffalo , he received an escort from mounted police. It was reported, “Every window along the way was occupied, and cheer after cheer greeted the tired figure, plodding, plodding, plodding, with a steady step. Several times men forced their way through the crowd to hand flowers to the old man. He would take the proffered gift with a smile.” A cannon fired when he reached a packed hotel where he was to give a speech.

To close out his second week he walked across fields instead of muddy roads and went over the 500-mile mark. He continued through western New York and was amazed at the reception received as he walked through the towns.

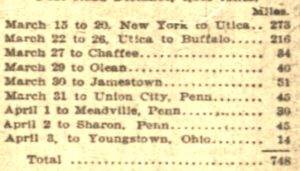

Pennsylvania

On March 31st, day 17, Weston entered eastern Pennsylvania. The roads along the way were so muddy that again his crew automobile became stuck in the mud and a hotel owner’s horse carriage followed him into Union City. He said, “I was met by about 50 strenuous and stalwart young men, who escorted me into the town. As I entered the limits I was greeted by screeching of whistles and ringing of bells from all parts of the city. There was also a military band, which escorted me to the hotel.”

On the following day, he felt faint during his walk but a farmer invited him into his home, giving him coffee and a piece of homemade cake that helped him continue on. He had not seen his automobile for two days, still delayed by impassible roads.

Weston wrote the next day, “Lost. One automobile, one chauffeur, and one trained nurse, incidentally several suits of underclothes, three pairs of boots, dozen pairs of socks, two dozen handkerchiefs, one oilskin coat, and one straw hat. Last seen in Jamestown, New York.” He did hear that it had a “busted engine.”

Ohio

Weston continued in Ohio. His automobile had been repaired but had not caught up to him yet. It rained hard and thankfully he had an attendant who he met along the way who helped him with rain clothes. The next day he walked in a terrible windstorm. “The wind had a velocity of seventy miles an hour and blew right in my teeth for twelve mortal hours. It knocked me all over the road and sometimes blew me to a standstill. Twice it blew me under a rail fence.” It was said to be the worst windstorm in fifty years that had ever hit that area. People kept coming out of their houses, trying to persuade him to stop for the day at their house, but he continued and walked 24 miles in seven hours. At Mansfield, Ohio, about 10,000 people welcomed him into the city. He decided to take a rest day there and let his automobile arrive with his personal supplies.

At many of the towns he stopped at, he took time to give lectures in the evenings. His dark early morning travel turned out to be a problem when he took a wrong road and his automobile got stuck behind in the sand. Some young men walked with him but “Soon we were walking in and out of the woods and ditches until finally we came to a house and heard the news that we were six miles north of the right road. A good-natured farmer got up and directed us how to reach the right road.” It turned out to be a ten-mile mistake that day which really bothered him.

Indiana

On day 30, Weston entered Indiana feeling well after a rare night of seven hours of sleep. Spring still had not arrived. He continued to walk through snowstorms and on frozen roads. Near Ligonier, Indiana, the school was let out early to let 300 students come out with the rest of the town to cheer him as he went by. Some nights he was surprised that rooms weren’t initially made available for him and some hotels would charge him very expensive prices. Other towns were very gracious and put him up for free. As he got closer to Chicago, he walked on the best roads of his journey so far.

Illinois

He decided to fire his chauffeur that had been driving the automobile since New York and he waited an extra day for a new driver to arrive. He blamed his original driver for letting him take the wrong road in Ohio and then didn’t make efforts to find him. On another day in Indiana, the driver just didn’t show up. Weston wrote, “It is absolutely necessary for me to have someone about me who can do something besides eat and sleep and give me a little attention. I propose to enforce more discipline in the future, and plan to walk more in daylight, except possibility if the sun get too hot.”

On the road again, Weston continued across Illinois. He hit a terrible four-mile muddy stretch and his automobile with his new driver became stuck in deep mud up to the hubs of the wheels. It took many men and a horse-drawn beer wagon, twenty minutes to pull the car out. Still not satisfied with his crew, he fired his male nurse/valet for losing some of his clothes and for being “too lazy to breathe without help.” His replacement immediately lost two new hats and allowed him to walk too far past his hotel. He grumbled that “walking is the easiest part of this task.”

Flooded roads were the problem west of Willingham, Illinois. “A new form of torture turned up in flooding the road, water 100 feet wide and 300 feet long. I thought this was a task for walking, but it seemed likely to develop into a swimming bout for three quarters of an hour.” He crawled under barbed wire fences trying to find ways through fields to get around the water but he still had to walk through knee-deep water. Weston was delayed by another off day because his new valet quit and the automobile “gave up the ghost.”

Weston caught a cold after his “swimming” experience. Now in the small town farm country, he was impressed by the kindness of the people. Word spread by telephone as he approached, and groups would come out in Automobiles and horse carriages to escort him into the Illinois towns. It had been a rough week with the delays and only 170 miles.

As he entered the town of Brooklyn, Illinois, he was arrested by a policeman. The officer later explained, “When a stranger walks through town with such a crowd following him, his suspicions were aroused.” He thought Weston could be an escaped lunatic. When Weston’s identity became known, the policeman apologized and let him go on.

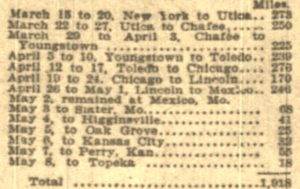

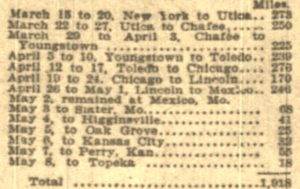

Missouri

On April 28th, day 40, Weston crossed over the Mississippi River on a railroad bridge and entered St. Louis Missouri, greeted by a very enthusiastic crowd and escorted to a big dinner at the athletic club. While going across Missouri he walked through his first thunderstorm that lit up his way and then he was pelted by hail. He tried to get some temporary cover and wrote, “I had great difficulty in getting shelter but finally succeeded after doing a lot of explaining to a farmer who was suspicious. I told him who I was and what my mission was, but he never heard of me and does not read the newspapers.”

Walking on the railroad had its dangers. He wrote, “I experienced a shock that seemingly overpowered my faculties. At Glasgow an immense iron trestle spans the Missouri River, and a person told me that there would be no trains either way for 30 minutes, so without the least hesitation I started to walk over the trestle. To my horror I discovered the trestle was nearly 150 feet above the river and nearly a mile in length. In case a train approached I had no way to escape except to jump into the river. I got very nervous and was getting dizzy. Finally, I arrived at the western end, but I was thoroughly weakened.” Two passenger trains passed him and tooted a greeting. He was starting to be recognized the train crews. Every time he arrived at a train station, the telegraph operators would share the news up and down the line.

Kansas

At New Cambria, he decided to start his next day at 1 a.m. Things didn’t go well in the dark. He wrote, “The darkness was dense and a strong wind blew me backward down the embankment from the Union Pacific tracks. I carried a lantern, which the wind extinguished. In vain I tried to relight it. I traveled on however, making only two miles an hour.” He had been walking more at night instead of during the heat of the day.

Near Russell, Kansas, Weston was caught in a severe “cyclone.” He wrote, “I sought shelter under the Union Pacific Railway bridge and found enough cornstalks and grass to make it quite comfortable. While waiting for the storm to blow over a covey of quail, a snake, and a rabbit visited me.”

On another day, as a bad storm appeared to be coming, he took shelter under an old railway platform. Soon a rancher with his family drove up in a wagon urging him to walk to their home a half mile away because the storm was going to be terrible. It should be noted that on his walking days, Weston never took rides to go anywhere, even when detouring off course. He wrote, “The ranchman sent his family ahead with the wagon and we walked to his cozy home together. Just as we got to his gate the storm broke with all its fury and I was drenched before I reached the door a hundred feet distant. The storm lasted for four hours. If it had not been for the thoughtfulness of my host in coming for and urging me to go to his house I should certainly have been attacked with pneumonia or lumbago. As it was, I enjoyed the perfection of hospitality.”

Colorado

Near Boyero, Colorado, he was delighted when a train engineer tossed to him a bag of ice. Soon after that he had a scare when he passed two “hoboes” sitting beside the track. They started to chase after him but Weston kept increasing his pace and eventually left them behind. He finished off his tenth week at Hugo, Colorado with a total of 2,396 miles. When he started this journey, he weighed 155 pounds and he now weighed 135 pounds.

Fierce storms continued to delay him on the Colorado plains as he walked on roads again. He wrote, “The road was sticky and I slid with every step.” He called the storms his “daily bath.”

From Denver, Weston turned north to go around the very high Rockies and headed to Greeley, Colorado. He wrote, “It is a pretty sight to see the snow-covered mountains with their irregular shapes and the many thousands of sheep, cattle, and horses. But farmhouses are scarce.”

Wyoming

Terrible headwinds made walking nearly impossible as Weston headed into Wyoming. He cut off seven miles by traveling cross-country climbing over fences, walking through cornfields, and bypassing Cheyenne. Of his night walks, he wrote, “The weather was perfect and the moon shone brightly. Coyotes were howling a serenade as I walked across country.” He reached Laramie, Wyoming on June 2nd in a starving condition. He wrote, “I was unable to get any regular nourishment. The towns are so far apart that it is impossible to get anything in the line of refreshments on the way.”

Weston continued to walk on the railroad bed. He said, “I passed through a tunnel half a mile long which gave me the horrors. Snow is everywhere from the recent storms. The massive hills full of large rocks and decomposed granite make such a wild and lonesome picture.”

Near Rawlins, Wyoming, Weston went through a downpour that lasted 69 minutes. “I was thoroughly washed and saved a laundry bill.” He said that the daily drenchings were getting monotonous. The recent storms had damaged the railroad so much that trains were delayed by 12-15 hours, causing his manager to fall behind unable to make arrangements for him ahead. He also didn’t eat regularly when needed because the towns were so far apart. Railroad workmen along the way tried to provide him help, but the section houses did not have much to supply for his needs. His manager with his baggage still had not caught up on the train and his shoes were badly worn out. The Union Pacific officials worked to eventually get his baggage to him that contained other shoes.

Weston wrote, “Another great annoyance is the hoboes who travel along the railroads stealing rides on freight trains whenever possible and some of them don’t look good to me. I am now carrying a revolver, but for what purpose I hardly know, believing that if I were attacked they would also take my gun.” Local deputies started to drive out the hoboes ahead of him which helped.

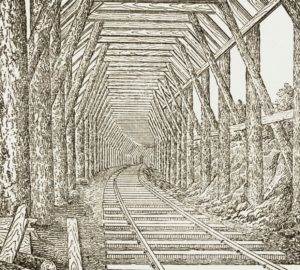

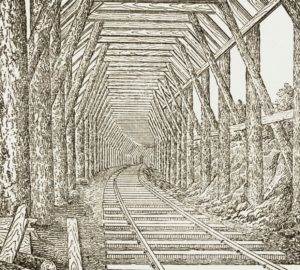

Weston faced going through the single track Aspen Tunnel near Evanston, Wyoming that had been completed in 1902 which was 1 ¼ mile long. The Union Pacific kindly made arrangements to escort him through the tunnel. He wrote, “With two workmen leading with torches, I started through the dark passage and reached the western end. We passed a great many men working in this tunnel laying a bed of cement and concrete of four feet thickness.”

Utah

At Ogden, he met with officials of the Southern Pacific Railroad Company to discuss using their railroad to walk on toward San Francisco. They agreed to have an experienced railroad employee follow him on a velocipede (three-wheeled human powered vehicle used to inspect rail lines.) It was propelled with a rowing motion and foot pedals could also be used. This was a great solution to supply him food, fluids, and ice every few hours as he traveled across the barren desert ahead.

Weston had decided to change his plans and not head for Los Angeles. Instead he would go directly to San Francisco. He explained that he had underestimated to challenges that slowed him down and thanked the Union Pacific for letting him walk about 1,500 miles on their transcontinental railway.

Of the west side of the lake, Weston wrote, “I am now and will be for the next two days walking on the great American desert, which is absolutely barren, and when the wind blows I am in a sandstorm, the particles filling my nose, eyes and mouth, almost choking me.”

Nevada

Weston crossed over into Nevada late at night on June 22rd. The railroad bed was very good to walk on and he walked many miles each day but avoided walking during the heat of the afternoon. In Nevada he had one of his highest mileage weeks and he gave credit to how well he worked with the railroad velocipede and its operator, Joseph Murray, who was the best helper he had ever had.

About 2-3 times per day, the conductors of freight trains dropped him off a piece of ice as they went by helping battle the desert heat. One day his hat blew off in the dark and it just couldn’t be found. The next day a train engineer saw it at the bottom of a ravine and returned it to him.

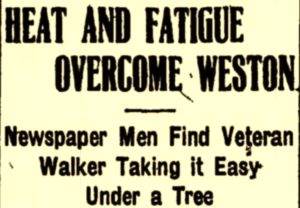

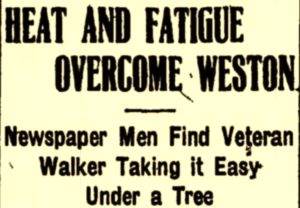

Continuing on, he really struggled because of fierce mosquitos. “Fancy one being on a broad, almost uninhabited prairie, not a tree to be seen, nothing but sage brush and black clouds of mosquitos.” The heat was oppressive. If he stopped at a house or hotel during the day, it was difficult to get rest because they were even hotter inside the buildings.

He finally admitted publicly that he would not make it to San Francisco within 100 walking days. “My health is good and I do not feel that I should take the chances that many others have taken on the desert to their sorrow.” He was detesting the western Nevada desert. “These is nothing here that tends to encouragement or induce pleasant walking. The natives themselves do not spare the unkind words about their desert.” He was discouraged that his original goals were shattered. He knew he was receiving criticism but he said, “The fearful conditions cannot be realized by any except those who have experienced something of them.”

As Weston approached Reno, Nevada, sandstorms pelted him and he couldn’t see 100 feet ahead of him. Thankfully he wore sand glasses. When he arrived at Wadsworth he was very pleased to see a river, trees, and grass again. He arrived at Reno on the night of July 6th. “Words fail me to express my appreciation in again being in a country where grass, and where the hospitable people of this place, 200 strong came out three miles and escorted me into this beautiful city.”

California

Weston walked into California on July 8th. “I passed through the most beautiful canyon in the world, crossing the line into California at 4:58 a.m. The scenery is simply grand. The Southern Pacific Railroad running beside the Truckee River, between gigantic mountains, presents a panorama.”

Weston’s greatest obstacle of his journey was going through about 42 miles of snow sheds protecting the railway from avalanches. He averaged just two miles per hour in them and wrote, “To exert one’s self to the utmost for nearly two days and nights, dodging the loose stones in nearly 42 miles of snow sheds over a series of mountains interspersed by standing between shed posts about every half hour to allow a train to pass and realize that it was less than twelve inches from your breast, while the terrific puffing of two immense engines nearly deafening you is certainly enough to make one nervous. Then add to this the walk along a narrow path for thirty miles during the night, having only a small lantern to show that a false step or a slip will plunge you into a canyon 1,000 feet below.”

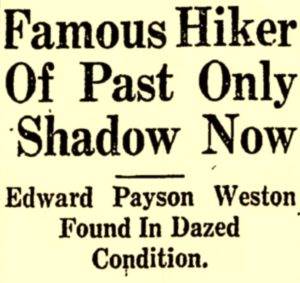

As the final days of his walk approached, Weston lamented that his walk was a “crushing failure.” He said his mistakes included going east to west against the wind, starting out with a bad automobile, and doing slow walking on the railroad beds.

Finally, the roads became very good as he walked through Sacramento and beyond. He continued walking on the railway. Railroad orders were sent to “keep a careful lookout for Mr. Weston on all trestles and come to a stop if necessary when finding him on a trestle to allow him to get to the end of it.” He had to cross over five long trestles and straddled a log within twelve inches of the track to allow a train to pass.

The Finish

On July 14th his walk came to an end. Knowing that he would need to take a three-mile ferry ride to San Francisco, he walked extra miles in Oakland. He then was ferried to his finish at San Francisco and arrived at 10:50 p.m. A crowd went with him on his way to his hotel. He looked to be a bit lame but still walked in his natural stride. After a good night’s sleep, he delivered a letter to the postmaster from the postmaster of New York that he carried with him.

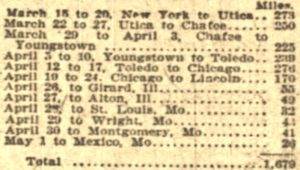

He counted his walking days at 104 days, 5 hours, and his distance 3,898 miles. But his total time, including his Sundays and other days off, was 122 days. He said, “Regarding my feeling and condition, I would say that I feel like uttering bitter words, but do not feel inclined to make excuses.” He received hundreds of letters and telegrams of congratulations. He at once started talking about walking back to New York and this time meeting his goal of 100 days. But he took a train and returned to New York on August 16, 1909.

The press cheered his accomplishment. “It had always been Weston’s ambition to make a walk across the American continent, and the fact that he has succeeded in his seventy-first year is a fitting culmination to the long career of pedestrian triumphs with which the name of Weston is associated”

It truly bothered Weston that he didn’t meet his goal for his 1909 of 100 walking days. Just the next year, in 1910, he set off again, this time from Los Angeles, California to New York City. He successfully finished in 78 walking days and 89 total days. But Paul Lange, another legitimate transcontinental walker quickly stole away his victory that year by doing the same crossing in just under 77 days.

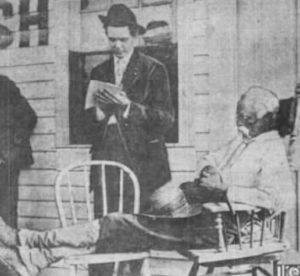

In 1927 he was struck by a taxicab in New York City on his way to church and was nearly killed. He didn’t see the car coming nor hear shouts of warnings. “A crumpled gray haired figure lay sprawled upon the pavement. Weston was carried into St. Vincent’s hospital close by and it was found that he had suffered head injuries which it was feared were critical for a man of his age and infirmity.” Weston spent three weeks in the hospital and never fully recovered, but was able to walk again, and three months later asked the court to dismiss assault charges against the driver which they did. Good people stepped in to pay for his hospital expenses, and arrange for him to live in Brooklyn. A celebrated play writer, Anne Nichols set up an annuity to support him with $150 per month.

Two months later, Edward Payson Weston died on May 12, 1929 at the age of 90 in Brooklyn, New York. He was buried in Saint John Cemetery in Queens, New York.

Read the entire transcontinental series:

- 1855 Walk Across South America

- Dakota Bob – Transcontinental Walker

- Zoe Gayton – Woman Transcontinental Walker

- The Wheelbarrow Man – Lyman Potter

- Edward Payson Weston’s 1909 Walk Across America

Sources:

- The New York Times, Jan-July, 1909

- USA Crossers – Transcontinental Crossings of America

- The San Francisco Call, Jul 15, 1909

- The Atchison Daily Globe (Kansas), Mar 20, 1909

- The Hutchinson Gazette (Kansas), Mar 23, 1909

- Buffalo Morning Express (New York), Mar 27, 1909

- The Des Moines Register (Iowa), Jun 27, 1909

- Sioux City Journal (Iowa), Jul 3, 1909

- Salt Lake Telegram, Aug 24, 1909

- The Oregon Daily Journal , Sep 28, 1909

- The Tennessean, Apr 7, May 23, 1909

- The Buffalo Enquirer, Apr 2, 1909

- The Buffalo Times, Feb 8, 1909

- Abilene Weekly Reflector (Kansas), May 27, 1909

- Ogden Standard, Jun 21, Jul 8, 1909

- Nevada State Journal (Reno), Jul 11, 1909

- The Evening News (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania), Apr 23, 1926

- Times Herald (New York), Jun 9, 1926

- The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Mar 16, 1929