Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 33:30 — 36.6MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

In Part 1 of this series, about walking around the world, I covered the very early attempts. By 1894, dozens, if not hundreds of walkers, started to participate in an “around the world on foot” craze. For many it was a legitimate ultrawalking attempt, but for most it was just a scam to travel on other people’s generous contributions.

In Part 1 of this series, about walking around the world, I covered the very early attempts. By 1894, dozens, if not hundreds of walkers, started to participate in an “around the world on foot” craze. For many it was a legitimate ultrawalking attempt, but for most it was just a scam to travel on other people’s generous contributions.

The typical scam went like this: They claimed that they were trying to walk around the world to win thousands of dollars on a wager, but they had to do it without bringing any money. They needed to be funded through the generosity of others, get free room and board, and free travel on ships. Walkers came out of the woodwork and the newspapers were fascinated by these attempts.

Eventually some in the press started to get wise. These walkers started to be referred derisively as tramps, globetrotters, cranks, fools, or “around the world freaks.” One reporter wrote, “A great majority of these wanderers upon the face of the earth are men who would rather do anything than work.” Another astute reporter identified many of these walkers as “frauds, traveling over the country practicing a smooth game in order to be wined and dined.”

Sprinkled in with these self-promoting frauds were also those who were legitimately striving to circle the globe on foot. Their efforts were real and very hard. They underestimated the difficulty involved yet had amazing experiences. There were too many of these “globetrotters” to even list. This article will share some amazing and bizarre tales of the naive, those that failed, the cheats, and the fakers. In the next article, I will share stories about successful walks around the world.

Samuel Wilson and Horace Yorke – British walkers – 1893

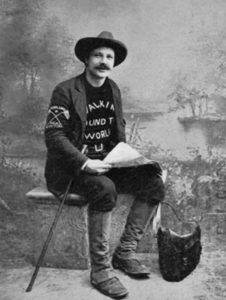

Those that went in pairs usually went the furthest. In 1894 two men from England started a unique walk around the world that would cross through Canada. Samuel Wilson, age 30, of Australia and Horace G. Yorke, an American living in England, both journalists, started their east to west walk around the world from Lincoln, England on August 11, 1893 and they were required to finish it in an unrealistic 18 months. Crazy restrictions were imposed as part of their “journalistic enterprise” that they could not spend any money on food or clothing but had to depend on the hospitality of others they met.

Wilson, a journalist, spoke six languages, claimed that he had previously walked from Cape Horn to Boston and had been the guest of President Grover Cleveland at the White House. (No evidence was found of this ever happening).

The paper wrote, “Nearly every person possesses a craze of some sort, but probably the latest development towards the extreme point of the sensation is that of Mr. Samuel Wilson who informed us that it was his intention to tramp round the world. He simply carries a satchel containing his register, wherein he gets subscribed his visits to the various towns he passes through.” Wilson was asked why he was really doing the walk. “I am engaged by the Sydney Bulletin for certain purposes and when my books are published, I shall of course, receive remuneration for them” Why was he going without money? “I believe a man can go through anywhere with civility. You hear a lot of nonsense and tomfoolery in this country about savages, but I have never been seriously molested by them.”

The two continued their walk across Canada going from railroad section house to the next, day by day and never camped out as they made their way to Calgary during the winter of 1893-94. “It was useless to carry food or water because both would become frozen. Neither was there any wood to build a fire, so that they must make the distance between section houses in a day’s journey.” In November, at Winnipeg they were kindly fitted out with complete buckskin suits of clothing to withstand the rigors of the winter. Wilson would visit all the police departments in the cities and would collect buttons which he sewed on this coat until he looked as if he were studded with brass nails.

Wilson liked calling himself the “King of Tramps.” One description of him included, “His pipe and himself are inseparable. His costume consists of a slouch hat, a Canadian frontier policeman’s brass-buttoned pea-jacket, and stout shoes with leather leggings to confine his trousers below the knee.”

Julian Rapport – “correspondent” walker – 1894

Julian Rapport claimed to be a correspondent for the New York Tribune. He showed up in Albany, Oregon, in February 1895, claiming that he was walking around the world and had thus far traveled 5,000 miles from New York, starting on July 4, 1894. He said he also took the northern Canadian route to Vancouver, was heading south to San Francisco and then to China. For money he carried only a specially milled ten cent coin that he was to return to the Tribune. He could not ask of assistance, could not work for money, but would work for room and board.

The San Francisco Chronicle looked into Rapport’s claim that he was employed by the New York Tribune and received a telegram from the Tribune stating that they did not know Rapport and denounced him as a fraud. That abruptly ended Rapport’s “walk around the world.”

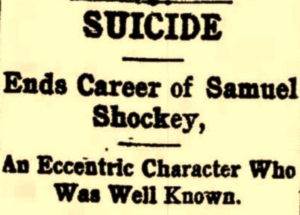

Samuel Shockey, The Pauline Pedestrian Pilgrim – 1894

But in December 1895, his trek went on. He showed up in New Orleans, Louisiana and he shared some of his background. He said that he had been stolen by gypsies when he was nine years old and lived with them for many years learning to read palms. During 1896, Shockey continued to travel to towns and was constantly arrested. In one town he decided to go to bed in the middle of a street, in another he pretended to hang himself from a city light pole.

In 1900 he was walking around the world again and in Pennsylvania he was put into a prison cell where he tried to hang himself again and then was committed to an insane asylum. He got out and continued to be arrested in many towns across the Midwest.

Finally, in 1922, at the age of 64, Shockey, claimed to be a civil war veteran who served with the 82nd Infantry (he would have been less than six years old then). While in Great Falls, Montana. He was picked up off the street, paralyzed drunk. The jailers were also a veterans. “The sergeant and corporal put the old veteran to bed and sounded taps,” Nothing more was found about Shockey.

Henry Thompson – The Pacific Slope Pedestrian – 1894

But this is how his visits typically went: At Buffalo, New York, “He was arrested last night for drunkenness and was liberated this morning. An hour afterwards he was drunk again and was put out of several saloons. After holding up several citizens for money, he was rearrested.”

At New York City in 1898, he said he was finishing up and only needed to walk back to San Francisco. For his world walk, he said he had stowed away on a ship to Liverpool, England, and walked across Europe, Asia, and Australia. His tales included narrow escapes from death when he was shot six times and once pierced by an arrow in Egypt.

During his visit in New York City, he was walking with his dog, Prince. While in a saloon, Prince disappeared, and when found again it had been painted a bright red. Thompson got into a fight with a man he accused of painting the dog, and was thrown out of the saloon.” He was admitted to the alcoholic ward at Bellevue Hospital.

Thompson claimed to have more than 17,000 receipts from telegraph operators along the way. He had worn out 28 pair of shoes and 243 pair of underwear. In 1898 he made very slow progress in Pennsylvania and New York, spending many nights in jail. He was last heard from in Elmira, New York in August 1898.

William McDade – Brooklyn walker – 1894

Some newspapers were skeptics about these globetrotters and others were very gullible. William McDade (1863-1901) was from Brooklyn, New York. He had served a year in prison for burglary in 1892-93. In February 1895 he showed up at the Daily Times office in New Brunswick, New Jersey, claiming to be from California. He said that he was walking around the world and had started from San Francisco five months earlier, in September, 1894. Their reaction was, “He is a big talker, and his story does not hang together worth a cent.” He declared to be a former president of the California Athletic Club and that he needed to walk around the world in ten months. The newspaper did calculations that he would need to walk 17,000 miles averaging about 65 miles per day.

At New York McDade said in order to win his $285,000 wager (nearly 9 million dollars value in 2019), he still needed to earn $6,500 and return to San Francisco. “Many persona laughingly gave the man small sums of money, saying his stories of adventure were worth it.” He intended to lecture in dime museums. But before he could get work, he was arrested and sent to a workhouse. On his release he had difficulty finding work and abandoned plans to “return” to California. It was said that he then drifted into bad company.

![]()

![]()

Dick Whittington and His Cat – 1895

He said, “I have to register at every railroad section house and post office on my route and at the capital of every state through which I pass.” Whittington had previous experience traveling long distances. “Three years ago I went around the world on a bicycle, being the first man to attempt the feat.” He had started in London, went east to west, crossed America on a northern route, sailed to China and completed his ride in 18 months. (No newspaper coverage has been found to prove that this ride ever took place.)

Americans did not at first understand the amusement of the Whittington-cat connection. In English folklore, a wealthy merchant named Dick Whittington lived in the 1300s had risen from a poverty-stricken childhood and made his fortune through his cat that was skilled in controlling rodent problems in the rat-infested country. The story became a famous play.

The press commented, “Compared to the others currently walking around the world he must be given credit for more originality in his outfit than any who have preceded him.” The cat was a mixed color cat and the dog was a five-month-old white bulldog named Blossom, Rowdy, or Britain, but didn’t look strong enough to put up with the “ups and downs of life around the world in a wheelbarrow.”

Whittington adapted the wheelbarrow so that it would work well on the railroad rails. “It has a large wooden wheel in front and a second wheel following it closely. Both these wheels have flanges, so that the barrow can be pushed along on one rail with very little effort. The vehicle is covered with canvas and presents the appearance of a diminutive prairie schooner. This is the home of the cat and the dog on whom so much depends in Whittington’s undertaking.” A handle extended out to the side of the vehicle allowing Whittington to walk in the center of the track.

On the canvas cover people would sign their names and included notes. An American flag flew from the vehicle along with a banner that with his name and proclaiming that he was the “wheelbarrow champion of the world.”

Whittington experienced challenges in the West. He reported, “I had a terrible tough time crossing the deserts and came very near starving to death, having for nearly a week subsisted on nothing but rice.” The railroad section stations were very far apart. The men stationed there were usually Chinese and lived on rice. He said, “When I pulled into Salt Lake City, I was nearly naked and so badly used up that I was forced to go to the hospital. I placed my cat and dog on exhibition and made money enough to pay expenses.”

Whittington’s cat died near the border of Colorado and Kansas. It had struggled with the altitude and poor diet going over the Rocky Mountains. He sadly said, “I gave my cat a funeral, but I had to officiate as gave digger, parson, undertaker, mourner, and all.” Most from the little town of Kanorado turned out for the ceremony. They had been very supportive. They located a burial plot behind the hotel, obtained a cheese box to be used as the coffin, and manufactured a tombstone that was appropriately inscribed. Finally a fence was built around the sacred spot.

Whittington explained that sometimes he let the dog ride because he could out-walk the dog. So far he had worn out six pair of heavy army shoes and a couple suites of clothing. He was described as “an intelligent looking young man and an interesting talker.” He was a small man, about 5’5” and weighed about 130 pounds. When asked why he was doing this, he responded, “I am not doing this for the money alone. I am doing it for the reputation. I wanted to do something that no one else has done.” He had a large rattlesnake skin wrapped around his hat and several large rattles dangling from the hat buckle.

He arrived in St. Louis, Missouri in October, after walking for six months. “He went in the evening to the exposition, where his quaint costume of sombrero, black sweater, and canvas leggings attracted much attention. He showed the book in which he collected all the official stamps of the post offices along the route.”

Whittington reached Pittsburgh in February 1896, but sadly two month later he was still there, in a hospital suffering from a bad attack of the “grip.” (respiratory disease caused by a flu virus). It was reported that he suffered from hemorrhages brought on by exposure, was in critical condition, and wasn’t expected to recover. On June 12, 1896, William H Bourne, Jr. also known as Dick Whittington died in a Philadelphia Hospital. He had traveled across America in what appeared to be a legitimate attempt, but sadly lost his life because of it.

John Thaler – Half Blind Walker – 1895

William John Thaler of Montreal, Canada, started his planned seven-year walk around the world on May, 5, 1895. He was originally from Austria. In 1892 he immigrated to Canada. Not long after arriving, he was amusing himself with some friends, doing tricks with a chair. While standing on his head on two chairs, one gave way, he fell and struck his left eye. After that he lost sight in both eyes and spent the next 18 months in a care center.

In late May, 1895 Thaler reached Ottawa. His planned route would take him to San Francisco, Japan, Hong Kong, India, Persia, Jerusalem, Greece, Turkey, Russia, Rome, Austria, England, and back to Canada. He hoped to cover 15-20 miles per walking day. In August he was in Michigan, averaging about 12 miles per day. As he was about to cross a bridge, he was arrested by the police. “Not understanding English well and seeing no badge distinguishing the officer, he smashed the pistol in the policeman’s hands with a piece of iron he carried.” He spent three days in jail. The authorities thought he was a lunatic

As Thaler was enjoying free room and board in Wisconsin, the story of his eye injury had changed. “Thaler was a clever blacksmith in the employ of a railroad at Montreal. One day a piece of iron flew up and destroyed his eyesight. In time he was able to see a bit with one eye, but he was unfitted for work. So he decided to get as much pleasure out of life as possible by making a trip around the world.”

While in Minnesota, he was making himself “a public nuisance” being drunk and was arrested for robbing a saloon till. He was sentenced to 25 days in jail.

In March, 1896, Thaler made it to Iowa, A description was given of him, “He wears dark clothes, with a Prince Albert coat, and although not shabby, each fiber tells the tale of long usage. Thaler is a well educated man and quite a linguist speaking several languages. According to his story he was formerly a physician.”

Salt Lake City commented on his strategy. “He carries no money, but more than offsets the lack with a prime quality of nerve. When he enters a town he goes to a hotel, tells the proprietor who he is and says that he wants to stay with him. His strange appearance causes the tavern-keeper to desire a chat with him and he is welcomed.”

In Nevada he had walked forty miles through the desert without food or sleep. He finally reached Wadsworth, Nevada and was so happy that he took out his pistol and fired it in celebration. He was arrested for discharging a firearm and spent sixty days in jail.

In March, 1897, Thaler arrived in Los Angeles, claiming he had walked more than 7,000 miles since he started nearly two years earlier. His story about his eyes changed again. He claimed to be an electrician, had an accident working, and was totally blind for over two years. He claimed that he next was going to head toward Mexico City, but four months later he showed up in Kansas. He still said he was walking completely around the world. But why did he reverse direction?

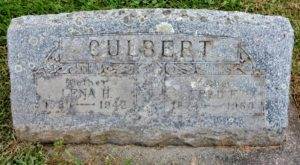

Fred Culbert “The Peshtigo Walker” – 1896

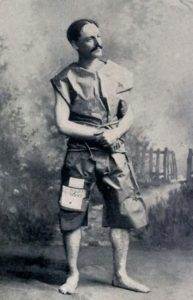

On May 1, 1896, he started from Kewaunee, Wisconsin to walk around the globe. “A large crowd gathered to see the start made, and the proceedings were enlivened by the presence of the City band. The young man was gaudily attired in black knickerbockers with red and brown hose, a red, white and blue belt and a brown sweater upon the breast of which were the words, ‘Fred Culbert, Walking around the world, three years, Kewaunee, Winconsin.’ On his head was an immense, white cowboy hat.” He planned to head to New York, then steam to England, and use the usual southern route across Europe.

It was reported that he started without a cent but could solicit donations to pay expenses. “He does not smoke, drink, or chew, and carries no baggage except a coat and a small valise containing testimonials from the mayors of some of the leading cities in the United States.”

Well, plans changed along with his story. In June and July, 1896, he was in Minnesota getting free hotel stays. What? He must have taken a wrong turn and was heading west. His story also changed. He said he started from Boston, Massachusetts on May 1st instead of Wisconsin. He also changed his starting story saying that he started wearing only a paper suit of clothes! But now, “He was covered from head to foot with medals and advertisements written in nearly every nook and corner of his person.” He said he was heading for San Francisco, California. His pace was very slow, averaging only 8 miles per day.

Strangely in August, he reversed course in Nebraska. In October, a Wisconsin newspaper got wise. They reported that he was heading back in Wisconsin telling newspapers that he had already been around the world and was finishing up. “Culbert is a gorgeous fake. He left Kewanee less than six months ago, got as far as Nebraska and is now coming back spinning weird yarns of countries he has never seen to every credulous listener.” They recognized that he was a lazy bum “and his truthfulness was lost the first day of his trip.”

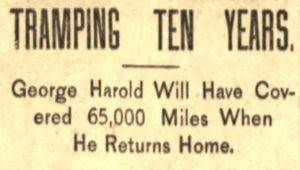

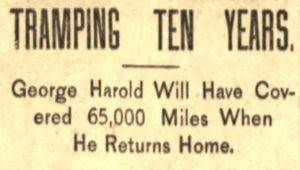

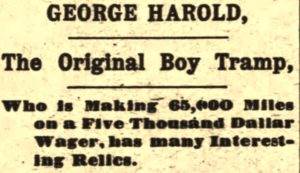

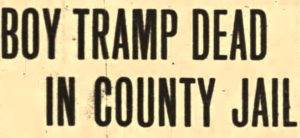

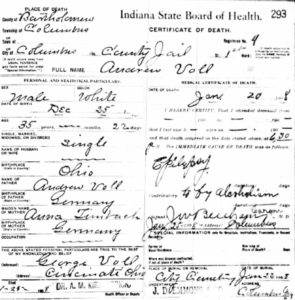

George Harold “The Boy Tramp” – 1896

An Oakland newspaper did a little due-diligence on the story. The Athletic club no longer existed. Its former director in 1887 had never heard of Harold before. No one in Oakland claimed to be friends with Harold. “He will have trouble in finding his relatives for they have long since changed their residence in Oakland and are nowhere to be found in the city.”

After his death, the true story of George Harold was told. About 1892, at the age of 19, he drifted into Columbus, Indiana and started working at the waterworks. He wanted a reputation, and a friend suggested that he start out as a “boy tramp.” The story continued, “A sweater was secured on which the words, ‘The Original Boy Tramp” were lettered, and Harold left Columbus and took the long trail. Supposedly, he was making a circuit of the globe, but he never got very far away from Columbus, returning two to three times a year. Throughout the years that followed, Harold was busy making his reputation. He was never anything but a tramp, but that was his ambition in life, and he was proud of it. He had enough clippings from city papers about himself to fill an extra large scrap book. He always brought back 2-3 dilapidated grips full of ‘junk’ and his imagination was so good that each piece of junk had its story. The man was harmless.”

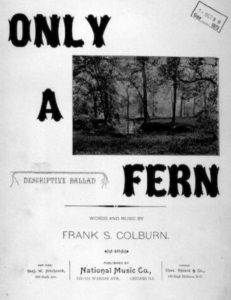

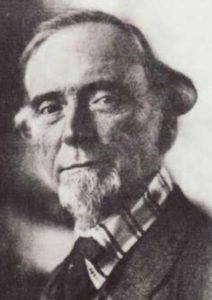

Frank S. Colburn “The Yankee Tourist” – 1896

Frank Saywood Colburn (1856-1932) of Maine, known as the “Yankee Tourist,” started his walk around the world from New York City on September 18, 1896, going east to west. He was one of the very few who was not walking for a wager with stipulations of poverty. He said he was doing it to study human nature and improve his health through exercise. He hoped to reach Paris for the exposition of 1900 and he said he was in no hurry.

Coburn was a newspaper reporter but also a talented and renowned song writer. He was famous for writing the music and lyrics for “Only a Fern” which he wrote in 1895. It was about finding a fern in his late mother’s bible, marking the parable of the prodigal son.

Colburn’s walk was viewed as highly credible. In July, 1897 at Grand Junction, Colorado it was written, “The gentleman is not one of the gushing globetrotters who have periodically pass through here. He has a definite laudable object in view and he never swerves for a moment from attaining it. His songs are nicely printed and are a valuable contribution to musical literature.”

Colburn described his trip across the Utah and Nevada desert, “Many times I nearly died of thirst and starvation. At one point where I was nearly exhausted, an engineer on a passing freight train threw me the remnants of his lunch, which probably saved my life. Section men, station agents, and hotel keepers generally treated me kindly. Through the great snowsheds of the Sierra, out into one of the most beautiful and romantic portions of California, I walked, and finally footsore and wearily reached Sacramento. From there to San Francisco I rode, because several years before I had walked over the same ground.”

There, he was unable to find passage to China. He joined the California Volunteers in 1898 when the Spanish American War broke out and hoped to be sent to the Philippines where he could then leave the service and continue his walk. But he was kept in California on heavy artillery coastal duty. He became disheartened as he couldn’t find passage to Asia. One day, a friend of his told him that he resembled Uncle Sam. Colburn decided it was his birthright and trademark. In 1899 he was mustered out of the service and given a nice benefit in San Francisco. He was highly respected and donned the persona and costume of Uncle Sam.

Colburn reached Seattle and tried to stow away on a steamer, but was discovered and thrown off. He claimed that he could have succeeded if he had discarded his Uncle Sam costume. He went to Victoria, Canada where he was met with a similar reception. He knew he was out of time to reach Paris for the world’s fair, so in July, 1900, he decided to start heading back to New York in a ‘go-as-you-please’ manner, riding or walking, stopping for lectures, and hiring out for advertisements. He would put himself on display in store windows to advertise goods.

In 1917 he started yet another walk to California still dressed as Uncle Sam. He claimed that it was his 20th cross-country tour and that he had walked nearly 20,000 miles for the past 20 years. He planned to walk 10,000 miles during the next three years. As he went along he performed a vaudeville act, as the original Uncle Sam. It became very successful. He didn’t end up in California, but for the rest of World War I, he promoted Liberty loans as Uncle Sam.

The Craze Continues

Even young boys were affected by the frensy. “Three Oklahoma boys recently started to walk around the world. They got 15 miles and then returned home to get something to eat.”

Starting these jaunts naked had turned into quite a fad. In Wisconsin it was reported, “Gust Johnson was found in the woods in a nude condition preparatory, the fellow said, to starting to walk around the world. The case is being investigated.”

Some tried hard to persuade the masses to wise up. “We welcome the fake with open pocketbooks. Let a man come who says he is going to walk around the world as an example. As a farm hand, working hard, and giving good value, he is not encouraged nor helped. But the day that he announces his determination to attempt a very foolish performance, to do something that is a wicked waste of energy that cannot possibly result in good to anybody, we open our purses and encourage him in his folly. We have no assurance that he will half accomplish his foolish undertaking, but take his word for it and shower our money accordingly.”

Some towns in the Midwest were through with the walkers. “The next tramp who arrives in town carrying a flag or a message from the Queen of Wahsitaw, or a letter to the mayor of Dead Beats Rest, or a note to the chief of Easy street, all of which necessitates a tramp around the world, should be arrested and put to work on a rock pile. Nine out of ten of this variety of globe trotters are dead beats and worse than common tramps. They do not go around the world and never intended to do so, but simply tramp and make money at it.”

Read all parts:

- Part 1 – Around the World on Foot (1875-1895)

- Part 2 – Around the World on Foot Craze (1894-96)

- Part 3 – Around the World on Foot (1894-1899)

- Part 4 – Around the World on Foot – The Bizarre

- Part 5 – Races Around the World on Foot – Dumitru Dan

- Part 6 – Walking Backwards Around the World

- Part 7 – Dave Kunst – Walk Around the World – 1

- Part 8 – Dave Kunst – Walk Around the World – 2

Sources:

- Jan Bondeson, The Lion Boy and Other Medical Curiosities

- The Baltimore Sun (Maryland), May 1, 1894, Dec 14, 1898, Feb 4, 1901

- The Philadelphia Inquirer (Pennsylvania), May 11, 1894

- The Derby Mercury (England), Aug 15, 1894

- The Gazette (Montreal, Canada), Aug 29, 1894

- Vancouver Daily World (Canada), Sep 10, 1894

- Weekly Herald (Calgary, Canada), Jan 2, 1895

- The Eugene Guard, Feb 5, 1895

- Albany Weekly Herald (Oregon), Feb 7, 1895

- The Daily Times (New Brunswick, New Jersey), Feb 12, 1895

- Statesman Journal (Salem, Oregon), Mar 10, 1895

- The Ottawa Journal, (Canada), May 27, 1895

- The San Francisco Examiner, May 10, 1895, May 24, 1896

- The Fresno Weekly Republican (California), May 31, 1895

- Portsmouth Daily Times (Ohio), Jun 27, 1895

- Lincoln Journal Star (Nebraska), Jul 15, 1895

- The Kansas Semi-Weekly Capital (Topeka, Kansas), Aug 6, 1895

- The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (Brooklyn, New York), Aug 12, 1895, Dec 13, 1898

- The Goodland Republic and Goodland News (Kansas), Aug 16, 1895

- The Topeka Daily Capital (Kansas), Sep 5, 1895

- The Topeka State Journal (Kansas), Sep 5, 1895

- Manhattan Nationalist (Kansas), Sep 6, 1895

- Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, New York), Oct 14, 1895

- Appelton Post (Wisconsin), Nov 7, 1895

- Sioux City Journal (Iowa), Nov 24, 1895, Mar 17, 1896, Jul 17, 1896

- The Saint Paul Globe (Minnesota), Dec 6, 1895

- The Times-Democrat (New Orleans, Louisiana), Dec 31, 1895

- The Democratic Standard (Coshocton, Ohio), Feb 7, 1896

- Logansport Reporter (Indiana), Mar 6, 1896

- The Record (National City, California), Apr 23, 1896

- Alton Telegraph (Illinois), Apr 30, 1896

- Green Bay Press (Wisconsin), May 1, 1896

- The Nebraska State Journal (Lincoln, Nebraska), May 2, 1896

- San Francisco Chronicle, May 8, 1896

- Buffalo Morning Express (New York), Jun 11, 1896

- The Buffalo Enquirer (New York), Jul 6, 1896

- The Daily Sentinel (Grand Junction, Colorado), Jul 25, 1896

- The Oshkosch Northwestern (Wisconsin), Aug 3, 1896

- The Salt Lake Tribune (Utah), Aug 15, 1896

- The Morning News (Wilmington, Delaware), Sept 28, 1896

- Appleton Post (Wisconsin), Oct 1, 1896

- Washington Times (Washington, D.C.), Oct 5, 1896

- The Daily Herald (Delphos, Ohio), Oct 30, 1896

- The Wheeling Daily Intelligencer (West Virginia), Oct 31, 1896

- Buffalo Courier (New York), Dec 6, 1896

- Wisconsin State Journal (Madison, Wisconsin), Dec 6, 1950

- Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, New York), Dec 10, 1896

- Green Bay Weekly Gazette, Dec 30, 1896

- Evening Sentinel (Santa Cruz, California), Feb 16, 1897

- The Dispatch (Moline, Illinois), Mar 2, 1897

- The Daily Times (Davenport, Iowa), Mar 23, 1897

- Omaha Daily Bee (Nebraska), Apr 11, 1897

- The Burlington News (Kansas), Apr 22, 1897

- The Daily Sentinel (Grand Junction, Colorado), Jul 1, 1897

- Pittsburg Daily Journal (Kansas), Jul 28, 1897

- The Jacsonia (Cimarron, Kansa), Aug 6,1897

- Nevada State Journal (Reno, Nevada), Aug 29, 1897

- The Leaf-Chronicle (Tennessee), Oct 20, 1897

- The Emporia Gazette (Kansas), Nov 16, 1897

- The Sun (New York City), Feb 19, 1898

- The World (New York City), Feb 20, 1898

- Dollar Weekly News (Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania), Aug 13, 1898

- The Standard Union (Brooklyn, New York), Dec 13, 1898

- The Houston Post (Texas), Jul 21, 1899

- The Capital Journal (Salem, Oregon), Jul 22, 1899

- News-Journal (Mansfield, Ohio), Dec 20, 1899

- Spokane Chronicle (Washington), Jul 10, 1900

- The Butte Daily Post (Montana), Aug 6, 1900

- The Inter Ocean (Chicago, Illinois), Nov 4, 1900

- El Paso Herald (Texas), Feb 11, 1901

- Holbrook Argus (Arizona), Sep 6, 1901

- Afton Evening Telegraph (Illinois), Dec 27, 1902

- The Lima News (Ohio), Mar 2, 1904, Feb 15, 1906

- Marysville Journal-Tribune (Ohio), Mar 10, 1906

- The Republic (Columbus, Indiana), Jan 22, 1908

- The Columbus Republican (Indiana), Jan 23, 1908

- The Evening Sun (Baltimore, Maryland), Oct 8, 1910

- The Washington Times (Washington, D.C.), Jan 3, 1911

- Evening Star (Washington, D.C), Jan 8, 1922

- Great Falls Tribune (Montana), May 14, 1922