Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 32:42 — 37.4MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

Get Davy Crockett’s new book, Strange Running Tales: When Ultrarunning was a Reality Show

Early backwards walking

On July 11, 1817, at Wormwood Scrubbs, England, Darby Stevens started to walk backwards for 500 miles in 20 days on a wager for 50 guineas. “A line is laid along the ground which is 200 yards in length, and which he takes hold of when he deems necessary.” It is unknown if he was successful.

The next day Daniel Crisp of Paddington, England took his place at the same location without the aid of a rope and walked 280 miles backwards in only seven days. A newspaper editorialized, “We have reason to believe that the idle scene of walking backwards, which continues to disgrace even Wormwood Scrubs, is encouraged for the very worst purposes and the public disgust will be still more excited, when we state that it is meant to continue these vicious scenes throughout the whole of the summer. Another of these reprehensible matches is already determined upon.”

In 1821 on a road near Bath, England, John Townsend walked 21 miles backward in 6:45. In 1822 he walked backwards 38 miles in 12 hours for three successive days. “This arduous task he performed, and won in great style, admidst the acclamation of a great number of spectators.”

Townsend really stepped up his backward game in 1823 when he walked 73 miles backward in 24 hours at Bristol, England on a mile out-and-back. “He commenced at midnight, a man preceded him with a lantern during the night.” He started walking 15-minute miles and large betting took place. Later that year he broke his record with 74 miles. Also that year, Townsend walked backwards 64 miles per day for ten successive days at Ipswich, England.

In 1824, Richard Sutton walked backwards 250 miles in six days in Sydney Gardens, in Bath, England. During the Pedestrian heyday of the 1870s and 1880, several individuals claimed that they were the “champion backward walker” and many matches were held.

Patrick Harmon – San Francisco to New York City

Patrick Harmon was born in 1865, in Ohio. By 1910 he was living in Great Falls, Montana working for the railroad. He also became a joint owner of Semaphone Cigar Shop at Great Falls. A new mayor was elected on a anti-gambling platform in 1913. Harmon’s place was scrutinized, and the law discovered that gambling was taking place in his establishment. It was raided an in October 1913, Harmon was arrested along with others, admitted that he had a card room, was found guilty and fined $100. In early 1915 Harmon sold his ownership of the shop, moved to Seattle Washington, and started to experiment with backwards walking in the mountains. A farmer friend, William H. Baltazor (1870-1949) also moved to Seattle with him to start over after a nasty divorce.

Harmon said that while in a Seattle club, a friend complimented a man for walking into the city from the suburbs. Harmon declared that he could do it walking backwards. The discussion progressed to the wager.

Walk begins

Harmon began his backwards trip from the Panama-Pacific Exposition grounds at San Francisco. “Backing carefully along his road and watching his path behind him only by means of a small automobile mirror fastened to a rod and a bracket on his chest. He seized his stick and knapsack and started out.” The two planned to average fifteen miles a day and raise money by selling postcards and selling subscriptions to a magazine.

On day four, Harmon was witnessed about 40 miles to the east, walking backward in Livermore Valley. “The first appearance of the walker in the distance was decidedly curious to the spectators. He carries a mirror attached by a spring in an ingenious way to his coat, which guides him somewhat in his freak undertaking.”

At Stockton, California he arrived at the newspaper office walking forwards and was asked why. “He replied that he had arrived walking backwards, but he could turn about when he entered a store or office, while in the city.”

Word of Harmon’s stunt spread in the newspapers across America. “The latest freak stunt is to cross the country on foot, walking backwards with his seat to windward.”

On only day 57, they arrived more than 1,000 miles to the west, in Salt Lake City. That would be averaging more than 22 miles per walking day, climbing more than 35,000 feet along the way, likely into snow, and nearly all very rough dirt road on the Lincoln Highway with small towns very spread out. The only detail he shared was battling a rabid coyote at Woolsey, Nevada. There is a huge problem with that story. He claimed to walk the Lincoln Highway across Nevada, but the town of Woolsey wasn’t on the Lincoln Highway, it was on the railway line, about 80 miles north of the Lincoln Highway. It is highly likely that they took train rides through this most difficult and slow stretch of the west. There were no newspaper stories about their arrivals in Nevada towns.

Harmon did not show any effects of the journey at Salt Lake City and put on backwards speed walking exhibitions at the Utah fairgrounds. He said he had developed very strong ankles and instep muscles and that “it would take a sledgehammer blow to sprain them.”

“Harmon was a locomotive engineer, a native of Cincinnati, Ohio. He is well educated, and while admitting that his test of endurance is a freakish one, he rather enjoys the novelty of it.” At some point on the trip, his “watchman” became ill and it delayed them eleven days. At Cedar Rapids, Iowa on January 18th, he estimated his miles to be 2,500 which comes to about 18 miles per walking day.

On February 13, 1916, Harmon arrived in Chicago, Illinois. A motion picture company produced a film showing him arriving in the city. He started to call himself the “champion backwards walker of the world.”

Near Pittsburgh in April, it was said, “they attracted a lot of attention as they hiked in over the Lincoln Highway, one of them walking backwards Both walkers were clad in drab colored walking suits, with leggings, and each one carried a canteen. They sold quite a lot of post cards while in the neighboring town.” In Maryland it was reported that many “automobilists” had seen Harmon as he walked through the county backwards.

Finishes in New York City

After his walk, Harmon went back to Seattle, Washington to live and work for the railroad. There was no news from Seattle if he won any prize. In 1917 it was discovered the Harmon’s true name was Patrick O’Rouke who had been going by an alias for years, for some reason, and he was from St. Mary’s Ohio.

His walk did cause very intense news coverage across America and likely did get the attention of future champion backwards walkers.

Jackson Corwin – Philadelphia to San Francisco

Jackson H. Corwin, born in 1896, was from Missouri, who became known as “the Human Crawfish.” On September 17, 1923, he started a transcontinental backwards walk of 5,000 miles from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania to San Francisco, California. He put together a booklet that explained his walk. Corwin was member of the Odd Fellows and was an author of humorous articles that had been published in a column in a Stockton, Missouri newspaper.

Corwin said he undertook the trip partly by accident. He overheard two acquaintances discussing the feasibility of a transcontinental hike in Philadelphia one night, where his mother lived. When one man estimated that he could do the distance in six months, Corwin exclaimed, “Why, I could walk it backwards in six months.”

He was initially accompanied by Judson Donnell who would be the official timekeeper and watchman to gather proof of his feat. He said he was sponsored by several athletic organizations who would award him a prize if he was successful. He was to walk the entire route backwards and stick to public highways whenever possible, but he had his choice of routes. Times would be recorded for his actual walking time and the overall time. He needed to finish in 500 walking days, averaging ten miles per day. He was allowed to accept generous donations, sell souvenirs, and was to collect signatures from public officials from each town he passed through with a population of 500 or more people. Making it even more difficult and impossible, he was not allowed to mail or forward any luggage or packages between towns.The public was urged to report violations. The “Ocean Gate Athletic Association” of Philadelphia certified the rules.

Walk begins

Witnesses did see Corwin walking. Issac R. Loy reported, “When about 20 miles from the District of Columbia boundary line, I met up with a man walking backward. I accosted him and learned that his name was Jackson H. Corwin. To save his neck from tiring by twisting and to guide himself, he was continually using a hand mirror. And I wondered to myself, what next.”

![]()

![]()

Bristol, Tennessee reported he came into town on December 3, 1923, having walked 556 miles so far in 78 days. “He is attired in hiking togs consisting of an army uniform. He carries a pack on his back containing traveling necessities which weighs about 40 pounds. In walking backwards, he uses a small hand mirror held up in front of his shoulder and sees where he is going by looking in the mirror. Tied across the back of his pack is a sign telling the world what he is up to. He attracted the attention of many motorists along the pike between Bristol and Abingdon.” He said he averaged about 15 miles per day “facing the way from whence I came.” He said his record was 18 miles. It was rumored that the prize money he was seeking was about $50,000. Along the way Corwin lectured. He walked about 10 hours a day and rested on weekends.

So far Corwin had only fallen down three times. He said he stopped for the nights mostly with farmers along the road and only three would accept money for lodging. Common comments were, “What is that fool doing?” and “When did he get out of the asylum? When he strikes a town after backing into his hotel, he discards the reverse and walks about like any other ordinary human, but when he leaves, he backs out of the same door he came in so as not to lose an inch.” His companion had changed to Ralph Bates from Los Angeles, California who came out to join him. “Bates walks directly behind him and warns him of rocks or any other obstacles in the road.”

Corwin was hit by a truck in Knoxville, Tennessee, but not seriously injured. He talked about the difficulties walking backwards. “It is more of a mental strain than a physical strain. I am especially interested in watching the reactions of the people we pass on the road. About half of them think we are crazy. Of the other half, some think we are doing some advertising stunt, and the rest are convinced that we are detectives. One woman insisted that I take along her missing husband’s photo and description so I could detect him too.” A common question he would receive was whether he was allowed to stop and sleep at night.

Walk interrupted

After Tennessee, Corwin was next heard from in Muldrow, Oklahoma on April 26, 1924. He had walked 1,546 in 149 walking days out of 222 total days. He was averaging walking about 5 days per week. No flaws can be detected his walking pace. But oddly, Corwin’s walk made a significant turn to the north for some reason, and he stopped for a significant time for some reason. He only walked 14 days in the next 137 days. No explanation was given. On September 10, 1924, Corwin arrived at Neosho, Missouri. He now towed a burro as he walked that carried his things including camping gear. He also carried some sort of instrument that measured the miles he walked. He said, “I guide myself by holding a small mirror in such a position as to reflect the road behind me. Being unable to see in this mirror after dark, I am forced to stop in the country more often than not, sometimes camping by the roadside.”

Walk ends in Kansas

Still heading north instead of west, on October 22, 1924, Corwin arrived at Fort Scott, Kansas. He explained that he was doing a zigzag course in order to get the needed 5,000 miles. He was selling a booklet about himself and his trip thus far. He changed his walk sponsor to a newspaper, The Bourbon News. This was a sure indicator that the wager/prize money story was bogus. Near the end of November, he was near Kansas City, Missouri, and gave a lecture to the Odd Fellows. He said he had walked 2,052 miles in 201 walking days in a total of 386 days. But Corwin soon quit his walk, and he was no longer reported in the newspapers.

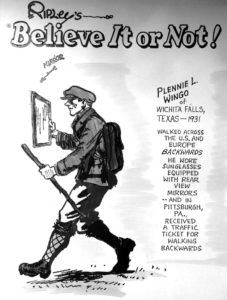

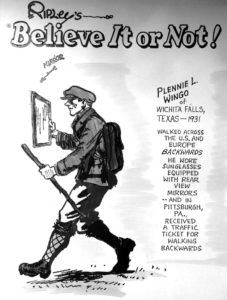

What appears to have happened, is that Corwin was likely doing a legitimate walk until about Neosho, Missouri, after a year’s time. He then knew he wouldn’t finish and headed north toward his home near Kansas City. He totally quit for several months, but returned to keep up a scam for a few more months earning money and giving lectures. Once arriving at Kansas City, Missouri, near his home, he quit for good. In 1930 Ripley’s “Believe it or Not” erroneously included Corwin in its series, stating that he walked all across the country backwards. Perhaps that inspired the next backwards walker.

![]()

![]()

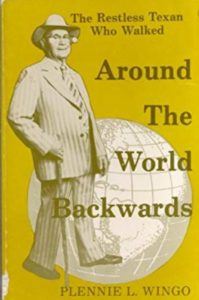

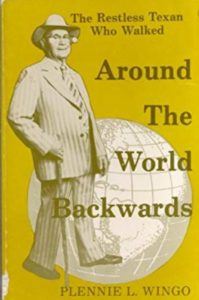

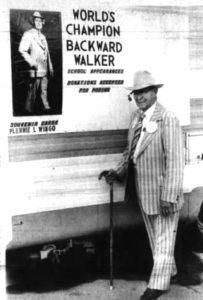

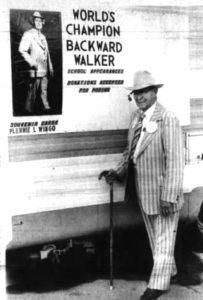

Plennie Wingo – Around the world

In 1930 he conceived of the idea to become an entertainer by learning how to walk backwards at a fast pace. He said the idea came to him when his daughter was talking to a high school boy at a party his daughter put on. The boy mentioned the amazing feats such as Lindbergh’s flight across the Atlantic, people sitting on flagpoles, and that a man had pushed a peanut up Pike’s Peak with his nose. He said there was nothing new left to be done and Wingo said that nobody had ever walked around the world backwards.

Perhaps he got the idea from those who came backwards earlier, but it appears that he thought he was inventing the concept of distance walking backwards. He said that for about six months he practiced in secret at night for 15-20 minutes each night so others wouldn’t steal his idea to walk the world backwards.

On March, 7, 1931, Wingo made his public backwards walking debut at the Southwestern Exposition and Fat Stock Show held at Fort Worth, Texas. He publicized his exhibition ahead of time, wearing a sign that read, “Walking Back to the Rodeo, Fort Worth, March 7 to 15.” He claimed to be “the first reverse walker of the world.” At the show he wore a cowboy costume and walked backwards wearing advertisements.

After that exhibition, Wingo was convinced to start his backwards walk around the world. “My friends kidded me about it, and that made me all the more determined to carry out my plan.” It was reported, “Wingo is beginning a world tour. He says he will walk backwards around the world. He climbs stairs, dodges pedestrians or automobiles and otherwise walks backwards and apparently about as good as the average person does normally. His only aid is eyeglasses which he wears and which have tiny mirrors at the side of each eye.” He bought the rear-view mirrors from a mail order house. They were advertised in a magazine as being especially helpful to bicycle riders.

Like others before him, his scheme involved selling postcards along the way. He said it was to raise money for the education of this 16-year-old daughter, Vivian (1915-1978). To his credit, he did not claim he was walking due to some phony wager. He later planned to write a book once his trip was complete. He would keep a detailed diary along the way.

World walk starts

By his second week, a story and picture of him had spread to most of the newspapers in America. “The same thing can be said of him that is said of a mythical species of backward-flying birds – He doesn’t care where he’s going, he wants to see where he’s been.”

At Muskogee, Oklahoma some boys tried to get him to accept a ride to the other side of town. Wingo replied, “If I took a ride with you, wouldn’t it be nice if I got a story in the paper that I was cheating? Just me knowing that I cheated would spoil the rest of my trip around the world.” In Joplin, Missouri, a policeman forced him to take his sign off his back because of a city sign ordinance.

Chicago

By the end of June, Wingo’s stunt was being featured on the Inquirer-Universal Newsreel seen in theaters. “He reports that motorists have been exceptionally kind toward him during his long walk, each one turning to one side as they pass him and waving a greeting as they pass.”

On one occasion he caused an automobile accident. “A motorist encountered him on a highway and turned in his seat to stare back at a man walking alone and backward. Another motorist approaching was also interested in Plennie. The two cars hit bang-on, but nobody was hurt.”

Injured

Marriage troubles

East coast America

In mid October 1931, Wingo arrived in New York City. It was a major milestone for his walk but he still didn’t have a major sponsor nor a way to get to England. He considered quitting and decided to move into a boarding house and get a temporary job in a cafeteria. He also worked on getting his passports and finding passage on a ship to Europe. He earned money doing publicity stunts set up by a manager, including walking backward along an 18-inch ledge of a 12-story building. His manager ended up swindling him out of the money and they got into a fight over it.

In December, he decided to continue walking and went to Connecticut and on to Boston, Massachusetts. At Providence, Rhode Island, he received a letter from his wife Della, informing him that she was through with the marriage. She had asked him to come home and he did not, so she was done with him. He signed the divorce papers. A newspaper included, “If Wingo carries out his intentions of going around the world in reverse, he will have to about face when he gets home to regain his wife’s affections. Mrs. Wingo has filed suit for divorce.”

“He wears sawed-off knee-pants and carries a stout cane, giving startled country folks along his way the impression that he is an escaped yodler from the Alps.” He had now walked about 2,500 miles and was determined to find a boat to England. He was asked why. “Well, it’s an ambition I’ve had for many years. There’s no competition in it, either. Besides, it’s a lot of fun. I’m outdoors, too, and I have a great chance to see the country, even if I do have to look at it backward.”

Europe

The head of a shoe company found Wingo passage on a ship to Germany by hiring on with the crew. He steamed to Hamburg, Germany on the Seattle Spirit, on January 12, 1932. He boarded the ship walking down the gangplank backwards. The work and travel was terrible and he suffered from sea-sickness for the first five days. At Hamburg, the steward would not allow him to get off the ship and held back his passport. He had no choice but continue to work on the docked ship. By the end of January, he left the ship while the steward was away.

Most of Wingo’s details of hi European walk came from a book he later published and it did not sell widely. In more recent years, Ben Montgomery published a fascinating book that used that material in The Man Who Walked Backward. Wingo started his backward walk in Hamburg, Germany as curious Germans wondered what the sign in English said on his back. Soon a man helped him with a new sign in German. He left the city on February 1, 1932 heading for Berlin, about 180 miles to the east. Along the way he was treated kindly by the country folk who invited him to stay in their homes after he showed them a news story that had been printed in the Hamburg newspaper. He said that his daily average miles were fewer than in America because he could not rely on getting rooms at inns. He had to develop friendships along the way and that took time. He arrived in Berlin on February 15, 1932. While there, Paramount Pictures took him around town filming a newsreel about him and earned $20.

Snow hindered Wingo as he continued 100 miles to the south to Dresden and through the German forests beyond, living off the kindness of others. He crossed into Czechoslovakia where the people frowned at his German sign. He made friends with a wealthy man in Prague who gave him a good new suit.

Near Sebes, Romania, after walking about 1,100 miles in Europe thus far, Wingo accidentally dropped his prized cane off a bridge into the water below. He climbed down the bank, stripped, and searched the deep murky water until he found it. “I got a cold from the plunge. It was raining and the rain was almost freezing as it struck.” He arrived at Sebes on April 15, 1932.

The American consul was not interested in helping Wingo, thinking his stunt was ridiculous and stupid. He was being charged for not having enough money to get through Turkey and being a nuisance to the public because of his backward walking. He gave assurance to the Embassy that if they would get him released that he would exit back out of Turkey. He was eventually released and stopped his backward walking. He stayed in Istanbul for awhile trying to figure out if he could continue, but eventually took a steamer to Marseilles, France and then worked his way on the ship Exeter to New York City where he arrived on June 15, 1932.

Analysis of European walk

Did that fantastic adventure really take place in Eastern Europe? There are problems with it. Yes, there is no doubt that he was there. There were some collaboration with other sources. But the primary source of these events was a book that Wingo later published. In the book, for some reason he didn’t understand how far he “walked” from Hamburg to Istanbul. He thought it was about 900 miles, but he was actually about 1,000 miles off; it was much further. His timeline and distance did not work well. The A.P. article places him at Istanbul on May 5, 1932 after he had already been in jail from many days. He left Hamburg on February 1st and journeyed about 1,900 miles during that time. He missed many walking days being held in jail and he never walked every day in a week. At most he had about 60 walking days. His pace on walking days in Europe would have had to be about 32 miles per day, an impossibility compared to what he had achieved earlier in America.

Wingo most likely highly embellished his European story decades later for his book and did not walk backwards all that way. He did end up in jail in Turkey, but his story there did not coincide with reports filed by the state department. Like most of the other globetrotters, he started his effort with integrity, but after his family broke apart and with money pressures, he eventually walked backwards into embellishment.

Return to America

In Phoenix, Wingo was arrested by police who said it was against the law to walk backwards within the city and taken to jail. He was told that he would be put in a cell with a murderer. When he asked to make a phone call, he was taken downstairs where he met an old friend laughing. It was all a gag.

Finishing in Texas

Wingo soon announced that he would go on a nation lecture tour “in interest of the unemployed.” It didn’t happen. Wingo wasn’t welcomed back to his home in Abilene because of his broken marriage. He moved to Archer City, Texas and worked as a cook in a café. His daughter Vivian later joined him to work there too. Della also later moved there and they later remarried but in 1931 divorced again. In 1946 he married a waitress, Jaunita, who was just three years old when he started his walk. She was 18 when he married her and he was 51. They moved around the country working in the restaurant business.

Bicentennial backwards Walk

For America’s bicentennial at the age of 81, Wingo, living in Los Angeles, announced that he would walk across the country backwards in five months. He started training by walking backwards each day, five miles to Culver City, California and back. “When I want a good workout, I go all the way to downtown Los Angeles.”

Plennie Wingo died in 1993 at the age of 98.

Yes, walking backwards was an ultrarunning thing. Will it ever return? Running backwards is also a thing and called retro running. The fastest known backwards marathon is 3:43 set by ZU Zhenjun at Bejing in 2004. The fastest known 100 km is 12:20, and the best 24 hours is 95.4 miles. Who will get the fastest known backward 100-miler?

Read all parts:

- Part 1 – Around the World on Foot (1875-1895)

- Part 2 – Around the World on Foot Craze (1894-96)

- Part 3 – Around the World on Foot (1894-1899)

- Part 4 – Around the World on Foot – The Bizarre

- Part 5 – Races Around the World on Foot – Dumitru Dan

- Part 6 – Walking Backwards Around the World

- Part 7 – Dave Kunst – Walk Around the World – 1

- Part 8 – Dave Kunst – Walk Around the World – 2

Sources:

- Ben Montgomery, The Man Who Walked Backward.

- The Lancaster Gazette (Jul 12, 1817)

- Hampshire Telegraph and Naval Chronicle (Portsmouth, England), Dec 31, 1821

- The Exeter Flying Post (England), May 16, 1822

- The Morning Post (London, England), Jan 9, 1823

- Berrow’s Worcester Journal (England), Dec 9, 1824

- The Yorkshire Herald (York, England), Jan 4, 1877

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Apr 17, 1907

- The Morning Call (Patterson, New Jersey), Nov 28, 1907

- Great Falls Tribune (Montana), Oct 19, 22, 31 1913

- The San Francisco Examiner (California), Aug 3, 1915

- Oakland Tribune (California), Aug 6, 1915

- The San Bernardino County Sun (California), Aug 10, 1915

- Stockton Daily Evening Record (California), Aug 10,12, 1915

- The Times (Munster, Indiana), Sep 17, 1915

- The Salt Lake Herald-Republican (Utah), Oct 3, 1915

- The Ogden Standard (Utah), Oct 7, 1915

- Great Falls Tribune (Montana), Oct 9, 1915

- The Nebraska State Journal (Lincoln, Nebraska), Dec 8, 1915

- The Banner-Press (David City, Nebraska), Dec 30, 1915

- Evening Times-Republican (Iowa), Jan 13, 1916

- The Gazette (Cedar Rapids, Iowa), Jan 19, 1916

- Oketo Eagle (Kansas), Mar 2, 1916

- The Dayton Herald (Ohio), Mar 11, 1916

- The Daily Notes (Cannonsburg, Pennsylvania), Apr 4, 1916

- Latrobe Bulletin (Pennsylvania), Apr 13, 1916

- The Evening World (New York City), May 22, 1916

- The Evening Review (East Liverpool, Ohio), Jul 31, 1931

- The Philadelphia Inquirer (Pennsylvania), Sep 18, 1923

- Cedar County Republican (Stockton, Missouri), Sep 20, 1923

- The Morning News (Wilmington, Delaward), Sep 27, 1923

- The Daily News (Lebanon, Pennsylvania), Oct 16, 1923

- The Birmingham News (Alabama), Oct 23, 1923

- The Salina Sun (Kansas), Nov 17, 1923

- The Bristol Herald Courier (Tennessee), Dec 4, 1923

- The Chattanooga News (Tennessee), Jan 12, 1924

- The Muldrow Sun (Oklahoma), May 2, 1924

- The Girard Messenger (Kansas), Oct 23, 1924

- the Tonganoxie Mirror (Kansas), Nov 20, 1924

- The Neosho Daily News (Missouri), Sep 10, 1924

- Corsicana Daily Sun (Texas), Mar 4, 1931

- Oakland Tribune (California), Apr 28, 1931

- Dallas Morning News (Texas), Apr 19, 1931

- Louis Post-Dispatch (Missouri), Jun 3,4, 1931

- Louis Globe-Democrat (Missouri), Jun 3, 1931

- Louis Star and Times (Missouri), Jan 8, 1931

- Daily Republican-Register (Mount Carmel, Illinois), Jun 8, 1931

- The Edwardsville Intelligencer (Illinois), Jun 9 1913

- The Pantagraph (Bloomington, Illinois), Jun 16, 1931

- The Philadelphia Inquirer (Pennsylvania), Jun 30, 1931

- Telegraph-Forum (Bucyrus, Ohio), Jul 18, 1913

- The Evening Independent (Massillon, Ohio), Jul 31, 1931

- The Evening Review (East Liverpool, Ohio), Aug 24, 1931)

- Hartford Courant (Connecticut), Dec 9, 1931

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Dec 24, 1931

- Las Vegas Daily Optic (Nevada), May 5, 1932

- Globe-Gazette (Mason City, Iowa), July 15, Nov 23, 1932

- Santa Ana Register (California), Aug 18, 1932

- Abilene Reporter-News (Texas), Aug 28, Sep 25, Oct 15, 1932

- El Paso Times (Texas), Sep 23, 1932

- Harrisburg Sunday Courier (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania), Dec 11, 1932

- Nebraska State Journal (Lincoln, Nebraska), Jan 8, 1933

- The Tylor Daily Press (Texas), Jan 12, 1933

- The Neodesha News (Kansas), Mar 11, 1943

- The Parsons Sun (Kansas), Jan 10, 1955

- The Lost Angeles Times (California), Apr 15, 1971

- The Indianapolis News (Indiana), Jan 1, 1972

- Shiner Gazette (Texas), Feb 20, 1975

- Chicago Tribune (Illinois), Apr 20, 1976

- The Californian (Salina, California), Jul 28, 1976

- Battle Creek Enquirer (Michigan), Sep 1, 1976

- The Honolulu Advertiser (Hawaii), Oct 14, 1976

- Green Bay Press-Gazette (Wisconsin), Nov 7, 1976

- The Californian (Salinas, California), Nov 11, 1976

- The Lompoc Record (California), Oct 4, 1978

- The Monitor (McAllen, Texas), Jul 3, 1989

- World Records for Backwards Running