Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 31:35 — 34.9MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

During the very late 1800s, people from various countries started to attempt to walk around the world for attention, money, and fame. In Part 2 of this series on walking around the world, I shared many stories of “fakes” who took advantage of the American public by traveling around the Midwest United States claiming to be on treks around the world, but making little or no effort to actually leave the States.

During the very late 1800s, people from various countries started to attempt to walk around the world for attention, money, and fame. In Part 2 of this series on walking around the world, I shared many stories of “fakes” who took advantage of the American public by traveling around the Midwest United States claiming to be on treks around the world, but making little or no effort to actually leave the States.

However, others at that time made more sincere attempts and successfully did extended walking on multiple continents, accompanied by newspaper stories confirming their presence in different countries. Several walkers were well-educated and certainly not the typical tramps and drunks that were highlighted in Part 2. Some of the individuals covered in this article became famous as explorers and were given credit for conducting valid walks around the world. But did they actually do it? What was their motivation for spending months and years in this activity? What did they do with their lives after their walk? Here are five intriguing stories of individuals who became very famous. They were a Russian, a Frenchman, a Greek. and two Americans.

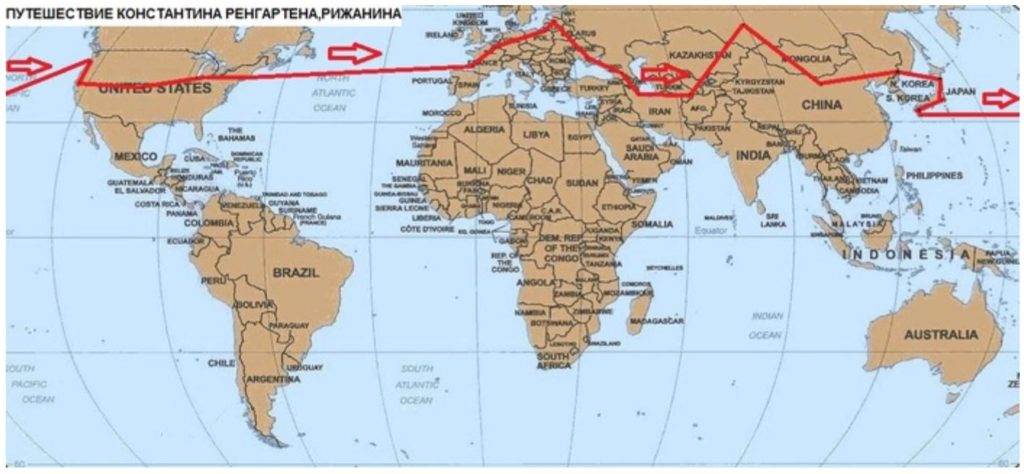

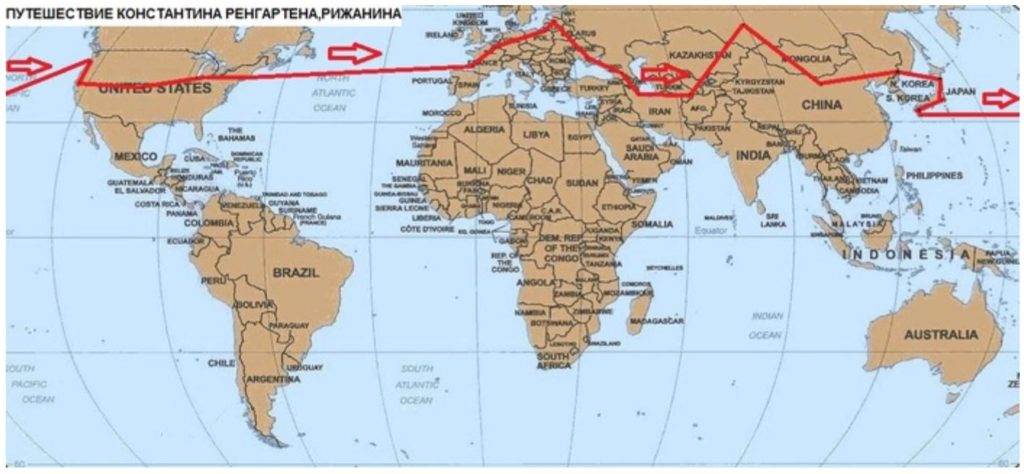

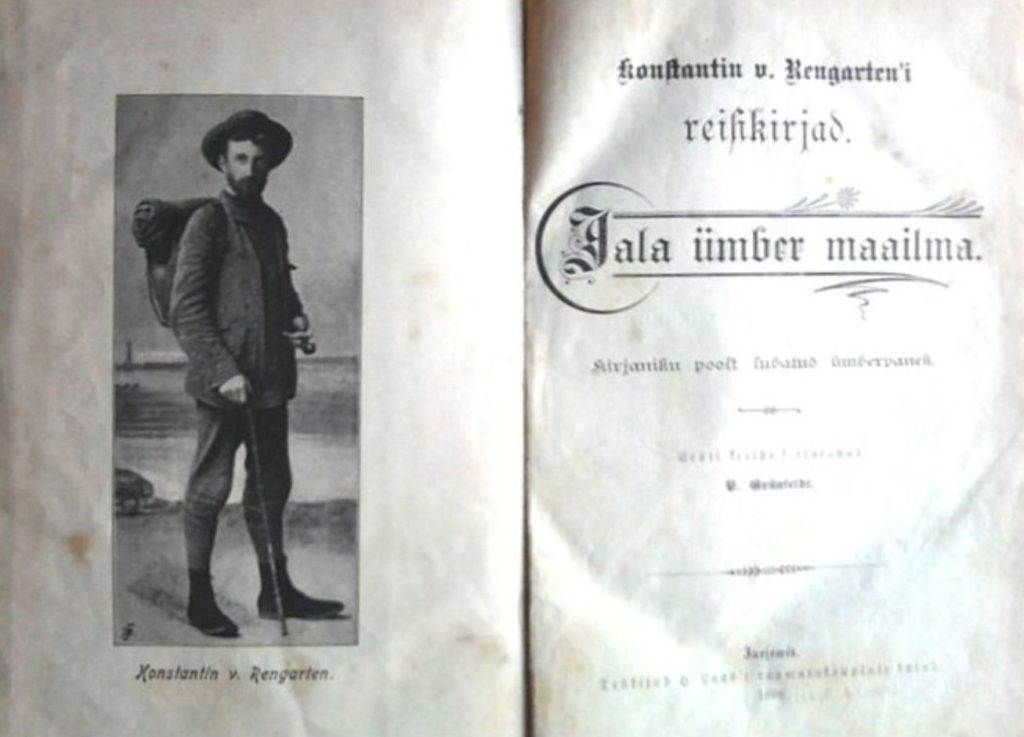

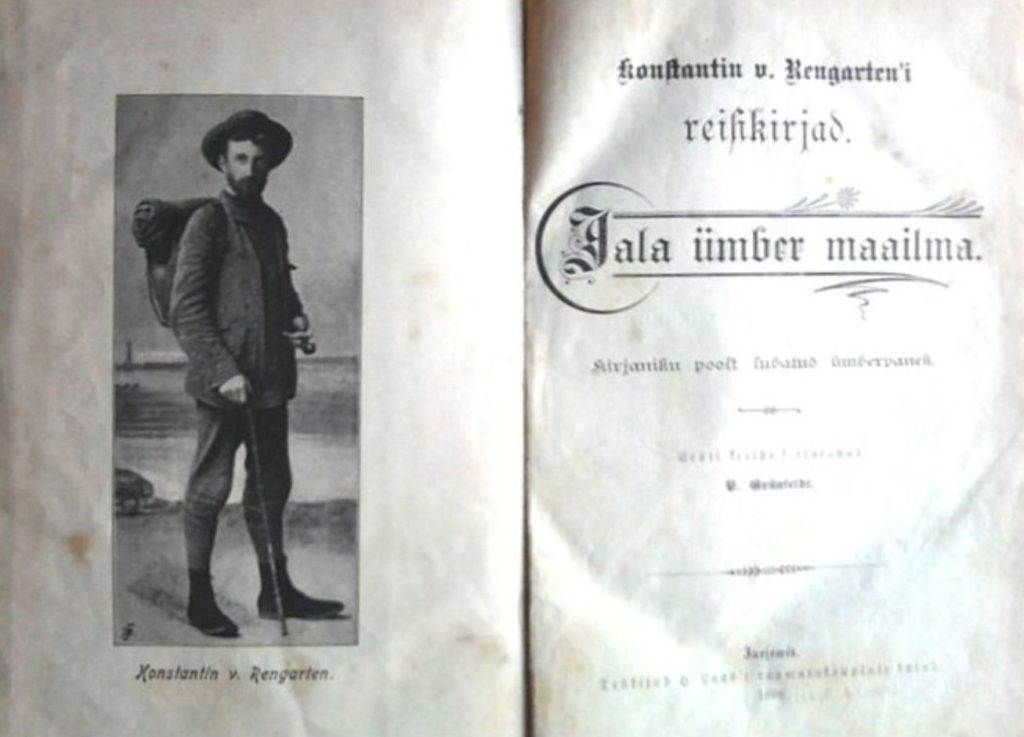

Konstantin Rengarten – Russian walker – 1894

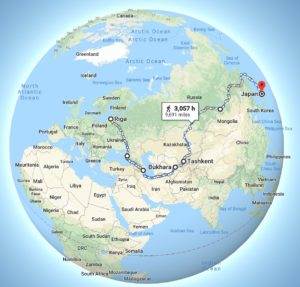

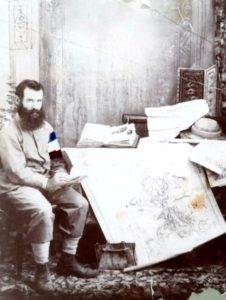

Rengarten started a walk around the world west to east from Riga, Russia (capital of present-day Latvia) on August 15, 1894. He was highly educated, rich, well-funded, and represented ten German newspapers and magazines, five that were published in Russia including the St. Petersburg Herold. He would regularly write columns to be published. He would also ship back home “all manner of specimens, rare and interesting, that are duly arranged and classified by his wife, who is an ardent scientific student.”

He spoke German, French, Russian, and a little English. He expected to walk for three years. Nikolai Greinert volunteered to go with him. Unlike most of the other globetrotters of the time, Rengarten did not travel due to a wager and paid his own way instead of expecting locals to always support him.

When they crossed through Ukraine, the rainy season slowed them down terribly. Greinert gave up and returned to Riga. Rengarten continued alone. In his backpack he carried climbing equipment, woolen underwear, a camel-wrap, a gun, a large hunting knife, a cooking pot, a camera, and a small supply of food.

“Rengarten wears only woolen clothes, and for the most part adopts the foot-wear used in the countries through which he passes. During the whole journey he has not once had to call in the advice of a doctor, but he has lost a good deal of weight.”

While traveling through East Russia he observed that the arrival of the railroad was having dire effects. The people’s lives were not improving with modern innovations. Instead, they were falling prey to drunkenness. Whisky was sold at five rubles per gallon, four as a tax by the government who encouraged its consumption to get money. He said in one city of 3,000 that he only found 150 sober people. In Tomsk, he met his wife who had traveled from Riga to see him after many months.

In Siberia, which was the most difficult stretch of his journey, Rengarten met some of the most famous and widely-known exiles of the day. From eastern Siberia he entered Mongolia and set out across the great Gobi Desert. He spent 36 days crossing it and was struck by the size. The nomads were very hospitable to him. The Mongols also helped him and respected his property. He reached northern China where he found many Russian merchants and then went on to Bejing. There he met Li Hongzhang, the Chinese viceroy. He then steamed to Japan where he stayed for four months.

During his travels through various countries, at times he was jeered and insulted for his foreign habits and costume. He was particularly critical of Japan, that published many articles about him in their press. He felt that he was treated with contempt and was said he followed by secret police as he walked in cities such as Nagasaki and Yokohama.

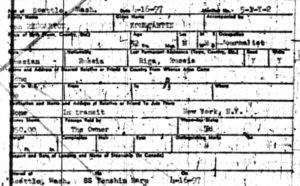

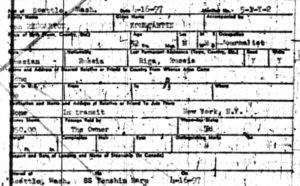

On April 16, 1897, after more than two and a half years, Rengarten arrived at Seattle, Washington on the steamer Tenshiin Maru from Japan. The ship had broken all known speed records, arriving in only 15 days, 8 hours. Her cargo brought 2,543 tons of tea, silks, matting, 700 tons of fireworks, and one globetrotter.

Rengarten claimed that he had walked more than 9,000 miles, averaging about 290 miles per month. He carried a scrapbook of newspaper clippings from the countries he had visited and said he ultimately intended to write a book about his travels. For his walking days, he estimated he covered about 25 miles per day. He preferred walking on wagon roads rather than railroad tracks and headed south through Oregon to California.

On May 8, 1896, Rengarten gave a free lecture at Salem, Oregon for the German population living there. He shared his interesting experiences while traveling through Persia and conditions in Siberia. About 50 people attended. He said he so far enjoyed walking in the United States and had high praise for the people of America who he said treated him nobly. He said was seriously contemplating making America his home after he completed his walk. He was taking a deep interest in the Native Americans. He visited a school for the blind in Salem and was very impressed.

Salem was very impressed with Rengarten, his “deep and studious habit,” and interest in natural history. “He is a man of means, entirely adequate to permit his indulgence in the time-taking method of pursuing his extended journeys in search of general knowledge. He holds it to be a flat impossibility for anyone to study nature faithfully while rushing over or through her domains at fifty miles an hour and hence he walks, enjoying the correlative privilege of stopping to observe closely whenever it is expedient.”

On June 15, 1897, Rengarten arrived at San Francisco, California after being on the road for a total of more than three years. “On his journey up Market Street, he was followed by a curious through of men and small boys, all interested to know the identity of the dusty and ragged stranger attired in a much worn and weather-beaten suit. He carried an Alpine stock and small bundle, weighing about 20 pounds, containing his accounts and worldly belongings. In spite of his appearance, the traveler has credentials to prove that he is all he claims to be – a Russian journalist making a tour of the world for the pleasure there is in it for him.”

After staying for two weeks, he left San Francisco on June, 30, 1897 with an unusual route through San Jose, Merced, Yosemite Valley, Mona Lake (July 22) to Reno, Nevada. From there, Rengarten walked the railroad to the east, stepping off the track when trains appeared, and reached Salt Lake City, Utah in September, 1897. There, he was seen accompanied by his Russian interpreter who walked with him. He estimated his walking miles to be 11,292.

At Kansas in November, it was noted, “His paraphernalia includes a knapsack, revolver, cane, notebooks, and very little else. His lectures are given at schools to pay his expenses.” He gave a lecture to a large audience in the chapel of Bethel College that was said to be “one of the best lectures ever given within the college walls.” Newspapers across the country would at times publish lists of unclaimed letters in their post offices, and often there were letters waiting for Rengarten, further evidence of his travels.

From New York City, Rengarten steamed to Le Havre, France where he was welcomed as a famous traveler. He walked through France, visiting Paris and welcomed at many cities. Through Germany, he lectured at universities at various cities.

A triumphal arch of flowers was built for him to pass through at the Russian border. On September 27, 1898, Rengarten returned to his starting point in Riga after a little more than four years on his walk. Everywhere were smiling faces with bouquets of flowers in their hands. He became very famous. “The streets of Riga were unusually lively – cries of cheers sounded, rejoicing reigned. So Riga met its resident Konstantin Rengarten, completing a trip around the world. The traveler crossed the Pontoon Bridge and headed straight to his apartment which drowned in flowers. The owner of a bookstore hung a portrait of the explorer in the most prominent place of his institution.” He was awarded the title of Honorary Citizen of Riga.

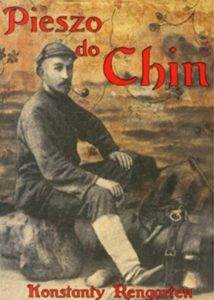

He estimated that he had walked 16,700 miles in four years, one month and 12 days. For his final 17 months, he significantly increased his weekly miles to a difficult, but believable, 105 miles per week. After his journey, a report of his travels was published in several countries and he gave several hundred lectures in Russia and Germany. In 1898 he published a book, Foot to China in Polish. In late 1898 Rengarten planned a hiking expedition to Tibet and back, but it was called off because of a lack of funds. Rengarten died in 1906 in Transbaikal, Russia, from pneumonia, at the age of 42.

Did Rengarten really do it? His timeline and route was very believable if you accept his fast concluding 17-month pace across America and through western Europe to Riga. Anyone who claimed to do it solo is highly suspect, but some accounts mentioned that he had a servant with him at times. His reports back to newspapers were many, and no reports were found doubting the authenticity of his walk. He never changed his story along the way. I have concluded that this was a fairly legitimate effort, perhaps the first true walk around the world.

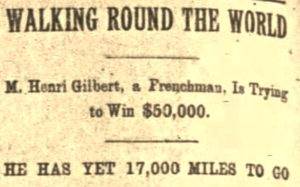

Henri Gilbert – French walker – 1895

In Syria, he was captured by a band of Turks, who asked him if he was Christian. They let him go once they learned he was a Frenchman. In 1896 he was near Baghdad and reported about torrential floods that caused the waters of the Tigris to rise so rapidly that the town came under serious danger. While Gilbert didn’t speak all the languages, he said he was a great believer in the power of mimicry, and by using a few signs he generally succeeded in getting what he wanted.

On April 2, 1898, Gilbert arrived in Adelaide and received a grand welcome from a large crowd. “Thousands of people followed him along King William Street to the post office, where he was heartily cheered.” He said he had been walking for more than three years and had traveled a total 23,220 miles. He next planned to walk another 1,500 miles to Brisbane through Melbourne.

In October, 1898, Gilbert arrived at Sydney, Australia and reached Brisbane on December 24, 1898. He intended to take a ship to China within a few days, but did not. By August, 1900 he was still in Australia. He married Marie Barat who walked with him for many more miles in Australia. A daughter was born on a ship on June 20, 1901. She was named Henriette Powell Marie. In October 1901, Gilbert and his family sailed for Hong Kong.

Gilbert’s walk continued to Port Said, Egypt, on the Suez Canal. Gilbert had also deserted another wife before leaving France. Simon Miller, a librarian from Australia, obtained information from a descendant of his first wife. Gilbert returned to France in 1903 but never returned to his original French family.

In 1909, he was arrested in Algeria for “non-presentation for a recall” from the army in 1908 and was sentenced to one day in prison. He may have served in the French military during World War I. Obviously, he never actually walked all the way around the world but certainly did walk thousands of miles in Australia.

George M. Schilling and his dog – 1897

From Pittsburgh to San Francisco and back

On April 20, 1896, Schilling started a walk from Pittsburgh to San Francisco and back with his St. Bernard named King, on a wager from an athletic club. He was required to cover the 7,500 miles in ten months, leave without a cent, and return with one thousand dollars. (The “wagerers” demanding to bring back money are red flags for phony wagers.)

Near the beginning of his journey, his dog became foot sore and exhausted, laid down, and died. In Ohio he was given another dog, a foxhound, which he named, King II. King’s sore feet limited Schilling’s pace.

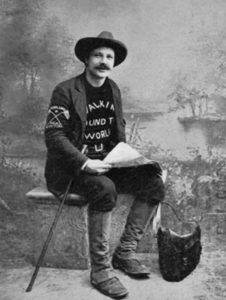

Schilling was described as, “a strong, tall man with a light complexion, blue eyes and light brown hair. His height is six feet, two inches, and weight about 170 pounds. He wears a maroon sweater, grey coat and hat, black tights and heavy laced shoes.” He walked mostly on the railroad and carried letters to prove he was a pedestrian and not a railroad hobo. After Wyoming, news coverage halted, but on August 24, 1896, it was reported that he arrived at San Francisco, only 26 hours ahead of his planned schedule.

He claimed that he walked 8,900 miles, taking 126 days to go west and 156 days coming back. He said he walked every foot of the distance which he “proved” by stamps, seals, and postmarks collected along the route. He returned with only a couple hundred dollars and thus didn’t meet the $1,000 requirement. He said he would never undertake such a long walk again.

Did he really do it? One must be very skeptical about this accomplishment due to the lack of coverage and lack of witnesses to his walking. After the first couple months of his trip, no details were given how he survived going across the western desert states with no crew support, and no mention of help from the railroad, a big red flag.

Within a few months Schilling was calling himself “the world’s champion long-distance walker” and was selling a book about the history of his life and adventures. A New York newspaper was skeptical and commented, “This book makes Schilling a greater discoverer of lands and peoples than the late Christopher Columbus.”

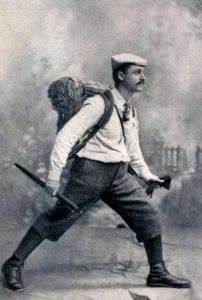

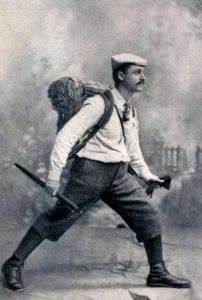

Schilling starts his walk around the world

On September 11, 1897, Schilling arrived in Detroit on a pace of about 20 miles per day. The press was skeptical of him. “Schilling has conspicuously placed on his blue sweater this announcement: ‘Walking Round the World,’ while ‘Champion Walker’ attracts attention to his cap.” In his knapsack he carried copies of his book that he was selling.

Schilling in Australia

Seven months later, on September 8, 1898, it was reported that Schilling was in Sydney, Australia. The ship had sailed slowly for 82 days. He wrote, “On arriving here, my dog King was taken away from me as they do not allow dogs to land in Australia. He was taken by the quarantine officers, who nearly destroyed him before I was able to secure bonds. It is likely he will fret and die in distress.” He was being held for six months.

Schilling’s around the world walk shifted from a point-to-point walk circling the globe to a walking tour of various countries. He prepared to walk 650 miles from Sydney to Melbourne. He arrived there on October 17, 1898. “The country people are very good. In the miles I walked from Sidney, I never passed a night without a good bed and plenty to eat.” At one point he walked 15 miles with aborigines who carried spears and boomerangs. He watched as they threw one and killed a bird flying overhead.

Schilling had joined a band of musicians and made a large amount of money finding time to perform. Returning to Australia in July, 1899, he was able to be reunited with his dog, King. About Australian conditions, he wrote, “There is a water famine in South Australia. Rabbits are dying by the thousands and all water holes are dried up. I have experienced very hot weather, as high as 115 degrees in the shade. I have had considerable hardships of late and was compelled to carry water for long distances. The dog is in good condition.”

Schilling in Asia

In August 1900, Schilling arrived in Sri Lanka and crossed India northward to Bombay where his dog King died in an accident. Schilling next sailed to Singapore and Hong Kong, where he arrived in March 1901. He claimed that due to wars in various regions, that he his wagerers granted him an additional year for his trek. (Changing wager terms were always another clue that the wager did not actually exist).

Schilling on Pacific Islands and Africa

Schilling said he sailed to Shanghai and hoped to walk through China but could not, because of the Boxer Uprising. This rebellion lasted from 1899 to 1901 and involved protesting attempts by westerners to colonize China. So, instead he went over to Japan in June 1901 and walked there. He next then went on to the Philippines and Indonesia and then was said to be in South Africa in October 1901.

Schilling explained what had happened during the past three years. He said he had great difficulty walking through Africa and eventually was arrested by the Turks who didn’t believe his story.

He reached London in November 1904 and then gave many lectures throughout the country, in no hurry to complete his goal. While there, he met and married a girl in Hull, England. He never returned to Pittsburgh that year. Instead he became a serious self-promoter, continuing to do stunts and “boasted that he was the first man who had ever walked around the world.” He said he had walked 55,000 miles in those seven years, averaging a stunning 650 miles every month, more than 150 miles per week.

His 1905 tales became highly embellished. He said, “Half a dozen times I nearly lost my life. Three times I was almost killed by disease. In central Africa I was attacked by natives and severely hurt.”

Despite earlier saying that he didn’t walk through China, he said, “In the Yunnan province of China I was beaten and left for dead. In India I was again and again attacked by villagers armed with bamboos, who tried to kill me because I slaked my thirst at their village wells, which they regard as sacred.”

Schilling presented his collection of 4,000 village seals and stamps that filled 28 books. He said, “The days I have spent in securing these certificates amount to a year and a half of the time. I collected two trunks of curios but one I lost and the other fell into the Zambezi River (in Africa) and the contents were ruined.” Also, seven years after he started, it was reported very widely that he originally started his journey only wearing newspaper clothing which didn’t happen. He had changed his start story to match a common story used by others.

Schilling stunts

Schilling finally returned to Pittsburgh in 1914 and died on May 9,1920 at age 45. His occupation was listed as “lecturer” and his death certificate included as a cause that he was “insane.” He left behind his wife, May, with five young children, including a new baby. His obituary included, “His death is mourned by a wide circle of friends, specially the old-timers who remember his achievements in the athletic world.”

Author, Jan Bondeson, wrote of Schilling’s trek in her 2018 book,The Lion Boy and Other Medical Curiosities, and mistakenly stated that “George M. Schilling was by far the most successful of the early would-be globetrotters.” The Guinness Book of World Records also incorrectly gave him recognition of being the first. Instead that credit should probably go to Konstantin Rengarten.

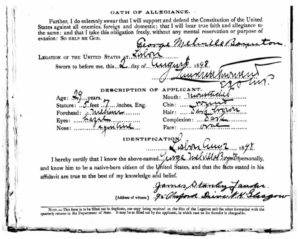

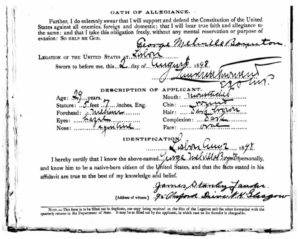

George Melville Boynton – explorer – 1897

Bonyton was born in Laconia, New Hampshire on July 15, 1869. His father eventually became a very successful cloak merchant in New York City. Boynton was well-educated in public and private schools. In 1889 after a serious argument with his father, Bonyton left home to never return when he was twenty-year-old. He falsely claimed that he went off to South America for a number of years, soldiering in various battles. Immigration records show that he actually went to London and then to Australia in 1889. He later claimed that during the next eight years that he had made six trips across the Atlantic Ocean instead of being in South America.

Like others, and with no witnesses, he began in a paper suit and eventually upgraded to real clothes before he left the city. There were no San Francisco newspaper articles about his start. He claimed that when he was 35 miles from Ogden, Utah that he was shot at by an Indian, but that was really his only hardship, He said that he only had to sleep out in the open for three nights on his journey east, a total impossibility because of the distance between towns and railroad section houses.

Boynton said one of his goals were to have audiences with all the rulers of the world. His planned route would take him to nearly every country and capital city in Europe and Asia. Boynton’s unbelievable story continued as he claimed to be entertained by President William McKinley at Washington D.C. on January 22, 1898.

In Great Britain

At New York City, a friend paid his passage to Liverpool, England on a steamer that left on February 20, 1898. He started walking around England and in April went to Ireland and walk there too. He said he needed to travel 40,000 miles on foot and said falsely that he had already been around the world four times and visited every country known to travelers. He said his around the world quest would end in Washington D.C. in 1902 when he would dine with the President of the United States.

To Boynton’s credit, his journey in Great Britain went according to his stated plans set months earlier and were backed up by numerous reports in England newspapers. In June 1898 Boynton was in central England heading north on zig-zag route in England. While at Edinburgh he married a Scottish woman. He had seen her picture in a photography studio and then went to Glasgow to pursue her. They quickly married on June 11, 1898 and they only spent one day together as a married couple. He left to continue his walk with a new young brother-in-law. News about Boynton was silent about his travels from there, but he told some fantastic tales.

In Spain

Boynton next steamed to Portugal on July 30, 1898, obtained a passport on August 2nd, and made his way from Lisbon to the border with Spain three weeks later. Strangely, Boynton, an American, wanted to walk in Spain just as the Spanish American War was concluding. He was denied entrance into Spain by border guards, but that night he crawled across the border on his stomach and was spotted by a sentry who opened fire. He made a run for it, successfully getting away and spent the night under an olive tree.

In his traveling kit, he carried, “several changes of underclothing, a sword-stick with a Toledo blade, and an automatic pistol.” Soon he was given a donkey to carry his things.

In another account, he said he simply greeted the mob by taking off his hat, bowing, and saying politely in Spanish, “A nice day, good evening ladies and gentlemen. They were stunned and did nothing. The police arrived and placed him under arrest.” While there he was borrowed 10 pounds and thus broke his wager.

Boynton said Spaniards tried to poison him along the way. Their plan was to get him to eat many Indian figs and then drink a certain wine which would cause a dangerous chemical composition of poison. “I ate my fill of the fruit, but when the wine was passed, I refused it. The natives were highly indignant at my refusal to partake.”

Bonyton said he was in Toledo, Spain in November, 1898 with the Austrian consul in a café. “The room was crowded with Spanish officers. They, knowing the consul, asked for an introduction to me.” They drank together and one of the men put poison in Bonyton’s glass. “I did not feel the effects of the drug until I reached my hotel. I was then taken deathly sick.” He forced himself to vomit and eventually recovered and went on to Madrid.

“The day I left Madrid I had to pass in front of 20,000 Spanish troops. I had the two America flags draped about my body. I thought sure I had done my last walking. But instead of being killed, I was cheered along the route” later claimed to be attacked later in a town by three bandits who he fought off.

He finally neared the French border. He said, “I had just arrived at Jaca, Spain, when a Spaniard accosted me and slapped me on the back and said, ‘Those colors of the Yankee are damn bad in Spain.’” They soon started to wrestle. “I shoved him away so as I could get my sword out of the case, but he came at me again with a knife and I shoved my cane at him. He grasped it and I gave a quick jerk and released the sword. He came again and I stuck him in the stomach and he toppled over the bridge, down an embankment to the stones below. I did not stop to see whether he died, but got out of town as soon as possible. I later found out that I killed him.” He quickly crossed over the nearby border into France on New Years Day, 1899, just in time because Spanish soldiers arrived one hour later at the border to arrest him for murder.

Boynton returned to England for medical help. He said he had to borrow $50 to make the trip and used that violation of his wager as an excuse to stop his trip. He went to Scotland to deal with his wife. After being married for only eight months, he filed for divorce, admitted he had been repeatedly unfaithful, and said that he intended to return to the United States to pursue mining in Colorado. He had no desire to bring his wife with him. Eventually his marriage was dissolved.

Expedition attempts

Reaching Colorado, Boynton claimed to beat the world record climbing Pikes Peak and then established a gold claim with a partner called the Motezuma Gold Mining and Milling Corporation and founding the city of Barnes. But it the claim turned out to be a fraud, seeded with gold from other claims. He went on to establish other companies that all failed and lost fortunes for shareholders.

Dr. Peter Attias – Greek walker – 1899

Before he was age 21, his father suddenly passed away and his relatives was expected young Peter Attias to carry on the business by his relatives. But he was determined to lead a life of adventure and began long journeys on foot in Syria.

Attias lived in California from 1891-92 bought horses in California for the British government and was very involved in the trade industry. In 1892, he was appointed chief of staff to a wealthy Russian exile, Prince Zamourim, who directed him to go off on a series of exploration expeditions in Africa, to the gold mines of Kilimanjaro and Rovensonry in Uganda. He also went on expeditions in Central America, had some dangerous encounters and was shot twice and stabbed with a sword. Upon the death of the prince, he returned to Europe and won fame by walking from Smyrna to St. Petersburg, a distance of 5,000 miles in 78 days. On another walk he crossed the Balkans and was decorated with the Order of the Cevailer by the Emperor Nicholas II of Russia.

It was said that Attias was extraordinarily intelligent and also was very strong physically. “His muscles are like bars of steel, and his mental activity is almost bewildering.” He could converse in twelve languages. But more recently a writer wrote that he was “one of the most polished of the around-the-world con artists” and was a habitual liar. Here is his walk around the world story.

One day he awoke one morning in London aware of the fact that only a few thousand dollars separated him from absolute poverty. He tried to think of something that might repair his fortunes when several wealthy sporting men offered to make him a wager.

On January 1, 1899, at the age of 26, Attias claimed to start a walk around the world with the London Sporting Club for $25,000. He needed to go 40,000 miles by land and 28,000 by sea, an impossible accomplishment, traveling only be foot and ship. An itinerary was planned with certain distance to be traveled in each country within three years.

Within two months Attias arrived in Omaha, Nebraska, accompanied by his secretary and two large St. Bernard dogs. He reached San Francisco by the end of September, 1899, making the trip across America in a little more than three months, averaging a very unbelievable 40 miles per day with scant news coverage. Naïve people reported, “He is a tramp of the first order, and is now in this country on a walking tour of the earth, visiting every principal country on foot.”

Attias then claimed to head southward through Central and South America to Valparaiso, Chile. He was impressed by Mexico but predicted that it would soon be taken over by the Americans. “The construction of the railway that has been made to unite the capital of Mexico will all that capitals of the United States is a signal of that future.” Columbia was experiencing a revolution. He said, “they live only to triumph in war.” He found Peru to be a beautiful rich nation and very hospitable. Given the pace he made his way through the countries it is very evident that he did not travel by walking, covering more than 8,000 miles in only four months.

Attias claimed that he completed his trek one month before the specified time accomplishing the terms of the wager. He next wanted to head to Australia and needed to cross the Andes Mountains in a hired four-horse carriage in February, 1900. While traveling on a mountain side road with a cliff on one side, and a roaring river down below, “about midnight the guide shouted back that there were obstructions in the road and stopped the carriage. Just as they pulled up, a rumble was heard, and a huge rock was seen tumbling down toward the carriage. Attias jumped from the carriage, but not in time to escape the shock. Carriage, horses, occupants, and Attias were hurled over the bank. The carriage and horses went into the river but Attias was found unconscious by the guide some time afterwards, lodged on the bank, haven fallen about 100 feet. Four men, including his secretary and servant were swept away and drowned. He lost his entire proof of his journey, including a collection of photographs and manuscripts.

Attias later claimed that he finished his trip in London with thirty days to spare and netted more than $100,000.

Attias continued to live a life as a con artist. He married multiple rich widows without getting divorces. He borrowed money that was never paid back. He gathered investors for companies or projects that never materialized. When he appeared in Salt Lake City, Utah, and conned the Greek population there in 1904 he was described as, “ a very much known impostor, who sometimes appears as a pedestrian, other times as a doctor, and other times as an enterprising person.” He was arrested there for practicing medicine without a license. In 1906 he was amazingly granted U.S. citizenship in Los Angeles, California.

In October 1909, Attias received a verdict of guilty from a jury trial. They only deliberated for two hours. “As an officer slipped the manacles on his writs, the ‘doctor’ asked his attorneys if they would comfort his wife. The conviction of the stylish little Greek was the sad ending of the dreams of many Detroiters, who lost their money in the proposed Globe Radiator Company.” He spent about a year in prison, moved to Portland Oregon and died in 1919.

Read all parts:

- Part 1 – Around the World on Foot (1875-1895)

- Part 2 – Around the World on Foot Craze (1894-96)

- Part 3 – Around the World on Foot (1894-1899)

- Part 4 – Around the World on Foot – The Bizarre

- Part 5 – Races Around the World on Foot – Dumitru Dan

- Part 6 – Walking Backwards Around the World

- Part 7 – Dave Kunst – Walk Around the World – 1

- Part 8 – Dave Kunst – Walk Around the World – 2

Sources:

- Baron Rengarten, Our Glorious Fellow Countryman

- Jan Bondeson, The Lion Boy and Other Medical Curiosities

- Sterliny Daily Gazette (Illinois), Aug 28, 1896

- Los Angeles Herald (California), Nov 8, 1896

- The San Francisco Call, Feb 22, 1894, Jun 1, 1894,Jun 30, 1895

- The Pall Mall Gazette (London, England), Jan 15, 1896

- Liverpool Mercury (England), Nov 3, 1896

- The Age (Melbourne, Australia), Mar 6, 1897

- The Standard (London, England), Sep 3, 1896

- The Pittsburgh Press (Pennsylvania), Apr 14, 1895

- Harrisburg Telegraph (Pennsylvania), Apr 19, 1895

- Pittsburgh Daily Post (Pennsylvania), Apr 29, Jul 13, 1895, Feb 19, 1897, Feb 28, Jun 5, Oct 16, Dec 25, 1898,

- The Fort Wayne Sentinel (Indiana), May 4, 1896

- Sterling Standard (Illinois), May 28, 1896

- Salt Lake Herald (Utah), Feb 20, 1897

- The World (New York, New York), Jul 22, 1897

- Detroit Free Press (Michigain), Jul 8, 1882, Sep 12, 1897

- Lincoln Journal Star (Nebraska), Jul 15, 1895

- The Wilmington Morning Star (North Carolina), Aug 3, 1894.

- The Standard (London, England), Oct 30, 1895

- The Capital Journal (Salem, Oregon), May 6,10, 1897

- San Francisco Chronicle (California), Jun 15, 1898

- The Salt Lake Tribune, Sep 3, 1897

- The Weekly Republican (Newton, Kansas), Nov 19, 1897

- The Times (Streator, Illinois), Jan 11, 1898

- The Guardian (London, England), Apr 23, 1896

- The Sydney Morning Herald (Oct 8, 1897, Jun 2, 1898)

- The Age (Melbourne, Australia) Apr 4,30, 1898

- Machester Weekly Times and Examiner, Jul 29, 1898

- The Seattle Post-Intelligencer (Washington), Jan 14, 1900

- Simon Miller, “The French Pedestrian and the Mystery Woman”

- The Fulton Democrat (McConnellsburg, Pennsylvania), Jan 13, 1898

- Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), Jan 17 1898

- Belfast News-Letter (Northern Ireland), Apr 1, 1898

- The Freeman’s Journal (Dublin, Ireland), Apr 11, 1898

- The Morning Post (London, England), Jun 18, 1898

- The Pittsburgh Press (Pennsylvania), Dec 19, 1897

- Omaha Daily Bee (Nebraska), Jan 8, 1899

- The Huddersfield Chronicle (England), Jan 10, 1899

- The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (New York), Jun 7, 1899

- The Ottawa Citizen (Canada), Aug 22, 1900

- Chicago Tribune (Illinois), Jun 13, 1899

- The Denison Review (Iowa), Aug 18, 1899

- The San Francisco Call (California), Sep 29, 1899

- The Butte Miner (Montana), Jul 9, 1899

- Buffalo Courier (New York), Aug 27, 1900

- Steve Frango, “The Greek Rogue of the American West – Part One”

- Detroit Free Press (Michigan), Oct 16, 1909

- Democrat and Chronicle (Aug 23, 30 1909)

- Detroit Free Press (Michigan), Sep 5, Oct 24, 1909

- Buffalo Weekly Express (New York), Jul 20, 1899

- Charles Roberts, “George Boynton: the greatest explorer that never was”

- Louis Post-Dispatch (Missouri), May 14, 1899

- The Brooklyn Citizen (New York), Jun 18, 1899

- Western Mail (Cardiff, Wales), Apr 21, 1900

- The Times-Picayune (New Orleans, Louisiana), Nov 32, 1900

- The Salt Lake Herald (Utah), Jul 29, 1904