Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 31:31 — 35.4MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

In 1873, Jules Verne published his classic adventure novel, Around the World in 80 Days, which captivated imaginations of the possibility of traveling around the world in a given time and the wonders that could be seen.

Also at that time, Pedestrianism, competitive walking, was in its heyday. Starting in 1875 individuals began to discuss if it would be possible to somehow walk around the world. Wagers were made and attempts began. They had no true idea how far it was or how long it would take. It wouldn’t be until more than 100 years later that some guidelines would be established for those who truly wished to walk around the world.

Yes, such an activity was real and still is today. How far is it to walk around the world? Today the World Runners Association has set a standard that it must be at least 16,308 miles. Early pedestrians were estimating that it would be between 14,000-18,000 miles. Today the fastest known recognized time is 434 days returning to the point of origin.

It all started in earnest around 1875. During that year, circumnavigation ultrawalkers emerged along with frauds who fooled the public to win wagers and made a living off giving lectures about their “walk.” Most American transcontinental walks of the 1800s involved fraud and fabrication. Some examples are covered in: “Dakota Bob – Transcontinental Walker.” The same was true for most early attempts to circle the globe on foot, but their tales are still fascinating. This multi-part article will share the stories and make some corrections on false claims that have been published in many books.

Corporal Lediard – 1786

But in January 1788, he was arrested by the order of the Empress of Russia. “In half an hour’s time, he was carried away under the guard of two soldiers and an officer, in a post sledge (sled) for Moscow, without his clothes, money, and papers and then taken back to St. Petersburg.” He was expelled from Russian, sent to Poland with orders not to return to Russia, and thus his walk around the world was foiled. “During all this time, he suffered the greatest hardships, from sickness, fatigue and want of rest, so that he was almost reduced to a skeleton. He said it had been a miserable journey but was very disappointed to not achieve his daring enterprise.”

Christian Frederick Schaefer – 1866

Christian Frederick Schaefer was a German who spent much of his entire life traveling. In 1866, about the age of 30, he said that he had been traveling the world for the previous 15 years. He reached Kansas and it was reported, “He has visited nearly all countries in Europe, Asia and Africa and is now en route to the Pacific coast. He estimates that he has traveled over 68,000 miles on foot. He has passports in fifteen different languages and his autograph book contains recommendations and signatures of many of the most distinguished men in this country and in Europe. He is a small man and has been suffering since his birth with a deformity of the spine. But he has unbounded energy and perseverance, is thoroughly impressed with the idea of making a tour around the world and will succeed.” His autographs included Andrew Johnson, Ulysses M. Grant, and Brigham Young. After crossing America he claimed to go across China and to Singapore. It 1867 he made it to Australia.

In 1882, it was announced, “Christian Frederick Schaefer died in a lunatic asylum near Sydney, Australia. He was always on his useless pilgrimages from his early manhood to a somewhat advanced age. He never worked unless absolutely compelled to on occasion and he begged his way over a large portion of the surface of the earth. His chronic spinal disease enabled him to appeal more confidently for charity. For many years he never walked less than 4,000 miles per year and it is estimated that his wanderings in all reached the extent of 150,000 miles. His life was a useless one. He was a superlative tramp.”

Mark Grayson – 1875

Mark Grayson, of Richmond, Virginia, was a very famous actor and political orator. In 1867 as pedestrianism was growing, he took up walking. At Leavenworth, Kansas, he attempted to walk 100 miles in less than 24 hours on a horse racetrack on the fair grounds. He succeeded with a time of 23:06 and sought to walk even further distances. He soon claimed to be a champion pedestrian, even better than the famed Edward Payson Weston.

In 1868 he announced plans to do a transcontinental walk from New York to San Francisco in 75 walking days. The large wager of $20,000 fell apart “on account of the treachery of backers”, but Grayson instead walked about 1,800 miles from Richmond, Virginia to Omaha, Nebraska, making 60 political speeches along the way carrying a “Democracy” flag.

Seven years passed. Grayson had returned to acting, but In 1875 at the age of 28, he started walking again and claimed to be “the champion pedestrian of the world.” Grayson’s promoter, Leon Macarthy worked to put together an enormous wager of $25,000 between two parties for Grayson to attempt to walk around the world. The plan was for Grayson to start from New York City on April 3, 1875, and to travel and estimated 19,226 miles in 600 days, arriving back at City Hall in New York on November 23, 1876. “He will start by steamer, across the Atlantic, and the distance that is traveled by water to be made good by walking on the ship.” His daily average needed to be 32 miles per day, Exceptions could be made for unavoidable delays, accidents, and if he was assaulted.

Announced walks that never took place

Henderson planned to visit the biggest cities in America and also visit Paris, walking aboard a ship if needed. He was to receive $50 per month for expenses and if he succeeded, receive $10,000. “He intends to keep up an ordinary diet, and to avoid the use of tobacco and spirits, as he has always done. He is perfectly sound in wind, limb, and digestion, and will drink little or nothing except pure water.” He was to begin the walk at the Rolling Skating Rink in Toronto, on May 1, 1878, but it never began.

In 1890, walking around the world was being discussed in France. A Frenchman estimated that a man could accomplish it in 428 days. 1891 M. Droz, age 34, of France, a former cavalry officer, announced that he would attempt to walk around the world in only 250 days, believing he could do it by walking 14 hours per day. “He has already several pedestrian performances to his credit, but that which he is about to undertake throws everything of this kind into the shade.”

Droz planned to start in Paris and head toward Moscow, traverse Siberia, and then take a ship on the shores of Kamtschatka (Russia’s far north-east) to San Francisco. He would then walk across America to New York, cross the Atlantic to Le Havre, France, and then finish by a walk to Paris. The walk never took place.

Russian attempt – 1890

Each day he would begin his walk at 8 a.m. and go until 6 p.m. with an average speed of 4 miles per hour when the roads were good and slower when it snowed. “His dress was very simple, a long black tunic, fitting close to his waist and buttoned up to the collar. Over it he wore a long, loose gray overcoat. He had a tarpaulin bag and carried no walking stick but a revolver was in his pocket.” For the first ten days he wore high boots usually worn by the Russian infantry, but they made his feet sore, so he switched to half-boots.

On arriving to Paris, France, it was observed, “Lieutenant Winter shows no traces of fatigue. He intended as soon as he arrived in Paris to shut himself up and to sleep uninterruptedly for two days so as to make up for lost time. But he had not reckoned on this own sudden celebrity, on the enthusiastic welcome he found on every side. Since his arrival he could hardly find time to answer the invitations he received and was truly the hero of the day.”

Unfortunately plans changed. He would not be able to walk across America because he had to be at his Siberian post in May. He returned to Russia on horseback with two French cavalry lieutenants. Typical of accomplishments like this, others wanted to make bets that they could beat it. Landais Dormon, who had climbed to the top of the Eiffel Tower on stilts claimed he could beat Winter’s time. A Russian officer announced that he intended to make Winter’s journey on all fours and return in the same manner.

John A Botzum – 1891

In 1891, John Augustus Botzum (1865-1958), a 25-year-old newspaperman from Akron, Ohio, started the first serious attempt to circle the globe on foot. Botzum was an accomplished young newsman. He started his newspaper career at the age of 16. By 1891, he left a large Akron newspaper to venture out on his own to create his own publication he called, “An Akron Boy Abroad; Around the World on Foot.” It was truly a novel idea.

He left on his walk around the world with Harry John Moule (1869-1927), who would contribute illustrations to his newspaper stories. On March 24, 1891, they departed from New York City on a steamer to begin their walk in Liverpool, England.

Europe

Their route wasn’t a strict west-to-east point-to-point walk across the world. From Liverpool they walked south and west and then took a ship west to Ireland where they walked about the country for a while, returned to England and went east across Britain to London. They then walked across France and wanted to enter Germany but were not allowed in because Moule didn’t have a passport. Instead they went to Switzerland. Their pace averaged about 20 miles per day.

They planned next to go to Italy, Algeria, Egypt and eventually to China. They admitted to the Swiss editor that “the constant walking often becomes monotonous.”

On June 12, 1891, Moule left Botzum in Milan, Italy to return home. He reported that Botzum was in “first class spirts and health, and that he walked from 16-20 miles per day.

The Middle East

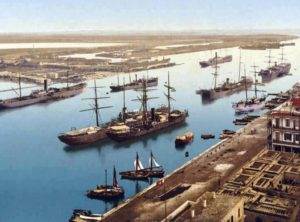

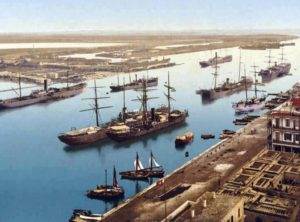

Botzum next bought a third-class steamer passage to take him to Egypt. He steamed across the Adriatic Sea to Austria, on to Turkey, skipping walking through Eastern Europe. From there he steamed to Port Said, Egypt, expecting to find funds waiting for him from his backers but was disappointed when the money had be misdirected. He was out of money. Others kept asking for some. “From the moment I landed in Egypt until I left, my ears are saluted with the cry of ‘Backsheesh’ which means money. I was surrounded by a mob of natives, dressed in loose, flowing garments, barefooted, and in many cases diseased, all yelling at once for ‘Backsheesh.'” He decided to return to London by sea and said, “I found myself once more landed in the great city with two empty pockets.”

Return home early

Botzum spent the next few months traveling and giving lectures. He said, “One of the objects of my trip was to prove how cheaply the journey could be made without missing any of the objects of interest.”

1892 “walk” resumed

On January 6, 1892, Botzum left New York City bound England again, this time alone. He started his walk at Rome, walking 162 miles to Naples. “From Naples I went to Pompeii, buried in the ashes of Vesuvius and stood on the crater of Mt. Vesuvius.” From there he went to Port Said, Egypt. On March 9th he was at Ismalia, Egypt on the Suez Canal, ready to continue his journey where he had left off the previous year. But then he went in the opposite direction and headed to Cairo. Clearly his plan was no longer to truly walk around the world. Instead he wanted to develop content for his newspaper. He joined up with an artist, James Rickelton.

Middle East

Of Cairo he said, “The atmosphere was remarkably clear and pure, and I could hear sounds at marvelously long distances. I stood on top of Cheops, the grandest of the Pyramids, and could hear the military bands playing in old Cairo, nine miles away and could see the shadowy forms of camels on the banks of the distant Nile. I saw the sphinx and gazed upon the sepulchre remains of kings and queens dead and gone centuries ago.”

He spent about four weeks in Cairo and one night slept on the top of a pyramid. In his letters he was usually very critical of the inhabitants of the countries. He described the Egyptians as “the worst kind of beggars, filthy, lazy, treacherous, and running about nearly naked.”

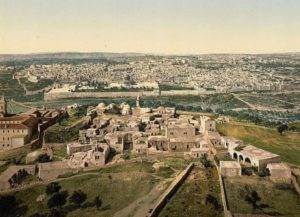

In April 1892, Botzum went to Jerusalem, by ship to Jaffa and then joined a caravan to the holy city. He was critical of the city. “When I reached Jerusalem, I thought the whole city would rush forth and take me by the hand and say, ‘we are glad to welcome you to your most holy city’ but they did not rush. The moral sentiment of Jerusalem is very low. I saw men gambling on the very steps of the church of the Holy Sepulchre.”

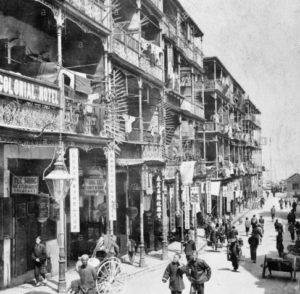

His journey continued but mostly by ship. He said he went back to Port Said where he was arrested for not having a passport. He avoided prison with the help of the American consul. He journeyed down the Suez Canal, across the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean and visited cities in India, Sri Lanka, Singapore, and went to Saigon, Shanghai, Hong Kong, and Japan.

Why an untruthful account?

Botzum didn’t do much walking at all after Europe. Just two months after being in Jerusalem, on June 27th, 1892, he arrived at San Francisco on a Chinese steamer, claiming that he had walked through Egypt, Arabia, India and part of China and Japan. He didn’t. Just riding a steamer for 24 hours a day would have taken him 35 days to go the distance. The San Francisco Examiner published a half page story about his journey, adding some countries that he had never walked in. Altogether he said that he had walked a total of 6,500 miles, a sad fabrication. It is estimated that counting both his trips, the miles he perhaps walked were about 2,000 miles at the most. Given his route, a full walk would have been about 14,000 miles.

Why the untruth? Ultrarunning historian, Andy Milroy commented about walkers such as Botzum. “The walkers depended a lot on the very believing nature of an often isolated people, who had little knowledge and understanding of what was involved in such walk. Likewise credulous reporters with limited knowledge had no true way to validate what they were being told. They needed a story and had deadlines to meet. The walkers started off with unrealistic naive expectations. The participants gradually compromised, took short cuts and aid, which were edited from their accounts and possibly from their memories. They often believed what they were saying. They became part of their fictionalized narrative. Using steamers, a walker could short circuit much of the world. They could walk through Europe, then catch a steam ship to the Far East, and then onward. The whole point was attention seeking and gaining status, that is fundamental to any society. They invested their lives in this type of activity because it gave them notoriety, a touch of fame.”

Across America

He next planned to walk across America on the railroad back to his home in Ohio. Botzum was a minimalist at this point. “He wears short knee trousers held up by a belt and is shod in heavy highland shoes. The only baggage he has is a small satchel, which he sends ahead of him to given points.” The press just couldn’t understand why traveling solo using this approach across the desolate west was an impossibility. He said, “Yes, I shall walk from here to Ohio, every step. I’ve walked 6,500 miles now, and the rest of the way is easy.”

Botzum started his transcontinental walk from San Francisco on July 2, 1892 and walked to Sacramento in three days and then to Reno in 11 days with just a few things in his satchel. In those days there was no good roads along the route over the Sierra and he would have had to travel on dangerous railroad tracks, dodging trains, with few communities along the way.

In Reno it was reported, “He looks fresh and strong and says his health is perfect.” Somehow he made it 600 miles across the blazing hot Nevada and Utah desert in only 20 days. He stated that while going across Nevada it was often impossible for him to find food or water and that many nights he slept on the sand and chased by railroad hobos.

He showed up in Salt Lake City, Utah on August 10th and later said he weighed 98 pounds when he arrived. He planned to spend a week resting, but four weeks later he was still in no hurry, visiting many communities, lecturing, and was well out of his way. He finally continued on and miraculously showed up in Colorado two weeks later using an impossible walking route at that time over the Rocky Mountains. He spent a couple weeks lecturing in mining communities.

In November and December he was lecturing in Nebraska and was still there in the cold winter. He abandoned his “walk” in Omaha, because of pressing lecture engagements in Ohio, and he took a train home. The Akron paper finally got wise and said his trip around the world was “on foot, horseback, muleback, camelback, and by boat and rail.”

Botzum soon made a successful career lecturing about his “walk” and a few people challenged his stories, seeing flaws. He said, “I have seen the dark side of life, and also the bright side. Of all the nations I have seen, I like Switzerland the best and think Japan to be the most progressive. But above them all stands our own beloved country, with better opportunities, better facilities, and better people.”

He now claimed that he had walked 10,240 miles (a huge exaggeration) during his trip and suddenly added Australia and Russia to the destinations he went to. He said he averaged 30-35 miles per day and wore out 20-25 pair of shoes besides many sandals.

In April 1893 Botzum returned to Omaha to complete his “walk” around to world that started in New York City. In reality it was just a lecture tour in Iowa with a manager setting up engagements. He said, “I am nearing the end of my journey and I am glad of it. Although my trip through Iowa has been very pleasant, there is not that novelty about traveling through the United States that there is in foreign lands and I will be overjoyed to reach home”

Botzum arrived back in Akron, Ohio on June 4, 1893. He didn’t finish the trip around the world to New York City. He retired from walking, married, and started writing a book. He continued lectures about his walk for many years and became editor of the Cleveland Press in 1902. For decades he was a very influential newsman and citizen of Akron, Ohio. For many years he wrote a column about the history of Akron and then did a radio show. Botzum died in 1958 at the age of 93 in a long-term care facility. He was called the longtime dean of Akron newspapermen.

James Swartz – 1892

James Swartz of New York started a walk around the world from New York City on October 15, 1892, choosing the difficult headwind direction of east to west along a southern route to San Francisco and then planned to take a steamer to China. He was doing it attached to a wager of $15,000 and had to walk 22 miles per day and finish in a naïve 15 months. On January 19, 1893 Swartz reached Denton, Texas. He had been recently sick for four days, but was still a day ahead of schedule. Nothing more was mentioned about him in the newspapers as he likely aborted his difficult trip in the harsh winter.

Edward Wilkie – 1893

His story changed that he was “walking around the world.” He said he walked most of the way to Chicago, but rode in wagons part of the way. He then went by boat down the Mississippi River to New Orleans and then by train to California. Thus, his effort was truly wasn’t a walk around the world, just trip by working and receiving aid from strangers. But he received a lot of attention by claiming he was walking around the world. At Los Angeles, he changed his story again, claiming that he was trying to encircle the globe within a year. From there his trip turned into a voyage around the world on ships to Australia, England, and back to America.

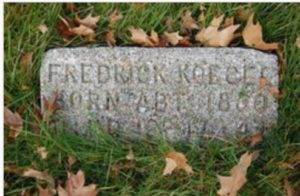

Gustav Keogel and three others – 1893

Finally, a truly serious attempt unfolded. In 1893, Four young men from Germany set off to walk around the world east to west, starting from their German home. They were Fred Meyer, a 23-year-old bookkeeper, August Jacoby, a 27-year-old butcher, Gustav “Gus” Koegel, a 28-year-old tailor, and Ludwig Blochs, a 25-year-old painter.

As they passed through Buffalo, New York after being on the road for three weeks it was observed, “They carried knapsacks and wore broad-brimmed straw hats and were sunburned and pretty tired looking.” At South Bend, Indiana they were allowed to bunk in the woman’s ward at the central police station and were guests of the mayor for breakfast.

They said that they were walking around the world without money, other than what generous people donated along the route. From San Francisco they planned to go through China, India, northern Africa, through Italy, and back to Germany.

It was reported, “There is something picturesque in their appearance. Large straw hats with the words ‘New York to San Francisco, 171 days’ adorned on their headers. Their shoes are large and heavy. They carry knapsacks on their backs containing a blanket and a change of underwear. They are bright intelligent appearing young men who spoke very little English.” From New York City to South Bend, their pace was about 31 miles per walking day.

At Chicago, they visited the World’s Fair and spent seven days reveling in the glories of the German Village. They were welcomed by the mayor given wide access to the city. A man, Adam Sommer was very impressed with the group. He quit his job and joined them for their trek to California. Later, while traveling the railroad through Illinois, a half dozen men jumped on them and tried to steal the musical instruments that they were carrying. They had a “desperate” fight won by the Germans who marched off playing “See, the Conquering Hero Comes.”

The company wisely took a southern route during the winter into New Mexico and across Arizona. In New Mexico, Koegel broke away from the rest because the others were more interested in making money giving concerts. At Flagstaff, in December, they arrived with some wealthy men from New York, and it was mentioned, “Mr. Blochs and Jacoby are the most excellent cornet players and their work was greatly admired at the World’s Fair when they played in the German villages.”

On January 24, 1894 Koegel, was the first to arrive in San Francisco, and claimed to finish his transcontinental journey in 169 days, 18 hours breaking a record of 192 days. Meyer and Sommer left the two musicians and pushed very hard for the last few days to come in under 171 days. The final two arrived within a couple weeks. Koegel said the only thing that troubled them along the was the bad water that they had to drink along they way. He further explained, “In the eastern part of the country we slept with the farmers in their barns and outhouses and in the West we put up over night at the railroad stations, or sometimes we slept in freight cars.”

This early transcontinental walk appeared to be legitimate. They planned to leave for China that April.

Gustav Koegel and Fred Thoerner – 1894

While at San Francisco, Koegel was offered a $10,000 wager to reverse course and walk easterly around the world accompanied with a 29-year-old German-American, Fred Thoerner (1874-1924) originally from Philadelphia. Thoerner, had been born in Germany, had been living in San Francisco for about six years, “was a good walker, and had tramped about the hills in the vicinity of the city.” Fredrick Gustav Koegel (1860-1947) was born in Leipzig, Germany and spent most of his youth in Munich and spent some years on South America.

The two would not initially be funded, could not beg or borrow along the way, but could raise money by selling photographs of themselves or giving lectures. They could accept room and board. “Under no circumstances were they allowed to ride in a vehicle of any sort, nor upon any kind of animal. In plain words, they were bound to foot every inch of the way, except when the use of ships was necessary.” Koegel accepted the terms, so he never completed his 1893-94 global walk with his German buddies. In 1895, Meyer did try another walk around the world starting from Berlin with a Max Weissner. They claimed to go through western Europe and then were in the southern states. They put on concerts to raise money, but nothing more was heard of them after Louisiana.

Koegel and Thoerner started June 10, 1894 and were required to report back at City Hall in two years, at noon on June 10, 1896. While going across Nevada, they arrived on the outskirts of a little place called Carlin, during a railroad strike. “It was getting dark and the first thing we knew, several men jumped up from the side of the track and made us give an account of where we were going and whence we came. After a while they turned us back, saying we could not enter the town. After about a hundred yards, fifteen or twenty shots were fired and we could hear the bullets buzzing above our heads. We made a break for the bush on the side of the track and lay there until daylight next morning. We learned then of the strike and that the pickets had believed us to be spies against the strikers.”

During this hot desert trek, at times they had to go without food and water for 48 hours or more when they failed to meet railroad men. They later explained that as they walked the railroad tracks, the railroad men all along the way welcomed them and gave them enough to eat. Back then, that was the only way to legitimately cross the remote west, with the help of the railroad.

About a month later they arrived in Ogden, Utah. In Wyoming, Koegel was laid up for nine days with mountain fever. Newspapers across the country did make notice of two arriving in their towns, but curiously, few details of their walking adventure were offered, just the same brief press release each time, explaining what they were doing.

Later the two observed, “We found the Missourians, or at least those who live in the isolated parts of the state, the meanest people we ever heard of. In some places the boys, women, and even the men abused us as if they were savages, throwing stones and sticks at us.”

They arrived in New York City on December 24, 1894. Thoerner was issued a passport on Dec 19, 1895. At New York City it was written, “The ‘peds’ have had good health. Thoerner has worn out two pairs of shoes and Koegel three. They have used the regular U.S. army shoes and find them easy and of remarkable toughness. Shoes of the best makes were found to be useless, the linings wearing and tearing until they became instruments of torture.” Their longest day so far was 59 miles. Their average was said to be a little less than 30 miles per walking day.

The two planned to sailed for Europe on January 3, 1895 bound for Portugal where they would continue their walk eastward. They then planned to head through Spain, Southern France, Switzerland, Austria, Russia, Siberia, and then take a steamer for San Francisco, for an estimated 12,700 miles of walking.

Europe

On January 12, 1895 their ship stopped in England. They showed off a collection of rattles from more than 200 snakes that they had killed during their journey across America. They also displayed a notebook containing postal stamps from every town that they had passed through in America with autographs of mayors and governors.

On June 22, 1895, Koegel and Thoerner arrived at Dresden, Germany, far north of their originally planned route. They then went to Munich and Berlin, and were six weeks ahead of schedule. They visited the American Consulate in Berlin where consul argued strongly to Thoerner against entering Russia because of his American citizenship. But he received papers to let them go to Russia.

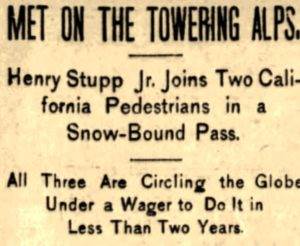

Harry Stupp joins the walk

“They had hoped to cross Russia and pass through Siberia by the Vladowostock route, but the latter was snowbound and would have been unpassable even if they had succeeded in getting into Russia. The Russians have been wary about granting passports to globe-trotters, and absolutely refused to allow the young Germans to cross the border under any pretext.” They had to change their route to go through Romania.

Separated due to sickness

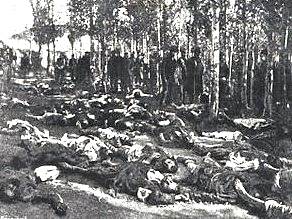

In Bucharest, Romania, Thoerner became seriously ill and lay in a hospital for about two months. Koegel and Stupp continued on. They headed toward Turkey. At Constantinople (Istanbul), they claimed they saw 400 Armenians massacred and another 800 killed at Trebizond. This tragic event was part of the Hamidian massacres. It was estimated from 1894-96 that up to 300,000 people were killed resulting in 50,000 orphaned children. Sultan Abdul Hamid caused this, attempting to maintain his collapsing Ottoman Empire.

Because of the violence, they aborted their travel through Turkey and took a boat all the way across the Black Sea to Batoum (Georgia). They then traveled by foot through the Caucasus Mountains and arrived at Tiflis (Georgia) on October 30, 1895. From there they went to Baku (Azerbaijan) on the Caspian Sea. They had suffered much while walking through the Transcaspian Desert and they had to go four days without food and water.

Middle East

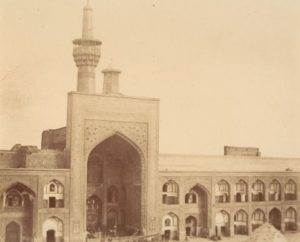

Koegel and Stupp next took a boat to Persia (Iran). They were weary about being in Persia where an American cycler had been recently brutally murdered. “But they have been guaranteed military protection and hope to make the passage in safety. They are well-armed though, so if the worse comes they will not be entirely handicapped.” They reached Meshed (Iran) on November 22, 1895. “The two travelers appeared to be in good health and spirits and not suffering from fatigue.”

Instead of going through Afghanistan, they headed south to Kerman (Iran) and then across Pakistan into India. They went to Bombay and crossed India toward Calcutta. While in India they had to sleep on tree-tops with tigers prowling around all night long.

Thoerner recovered, traveled back to Italy and took a steamer all the way to Alexandria, Egypt in late December, 1895. After visiting Cairo, he steamed for Calcutta in eastern India and waited to link back up with the others. Thus, Thoerner had to skip thousands of miles.

Asia to San Francisco

On June 5, 1896, Thoerner arrived in San Francisco without Koegel and Stupp. He finished with five days to spare but the wager was still lost. Koegel returned about July 1st. One of the stipulations of the wager was that Koegel and Thoerner had to stick together. Thoerner made no mention of his sickness and instead said they became separated trying to go through Siberia where he was not allowed to go in with Koegel. He said that he instead went through India (which he didn’t). Thoerner untruthfully claimed to have walked the entire trip.

The San Francisco Chronicle mentioned that Koegel and Stupp were invited to ride in the July 4th Parade. Stupp told exciting tales of their adventures. He said they met the King of Romania, the Sultan of Turkey, and the brother of the Shah of Persia.

Transcontinental walk to New York

Did Koegel and Stupp really walk around the world? Clearly not all the way. The details and evidence left behind, and sparse news coverage indicates that some of it was likely fraudulent. But of all the early claims of walking around the world, their claim left the most convincing evidence for being fairly legitimate, given the world circumstances of the time.

Koegel’s later years

“Mr. Keogel carries with him an album which briefly tell, with signatures and small photographs, the story of his wanderings. Here there are the signatures of notable persons and others, kings, queens, presidents, governors and reporters and other small fry. Of the small towns he passes through he collects the postmarks. He has notices in every known language of the world including Hebrew, Russian, Chinese, and languages whose names are hard to pronounce.”

That year he was seen in Ohio and New York on a bicycle, claiming that he was riding around the world for the fourth time. He also filed a law suit against a railroad during that trip. He had been sideswiped by a train and broke his arm. Transcontinental fraud, Dakota Bob, issued a challenge to race Koegel for 1,000 miles. Koegel sad Bob was a “bluffer” and that he would race him anytime.

In 1910, Koegel was at Keokuk, Iowa attending a lecture by another globe-trotter. Koegel wore a sold gold medal that was given to him by a New York City newspaper “for walking around the world and establishing a record of twenty-two months. Koegel expected to go after the record of Weston in a walk from New York to San Francisco.”

Charles Randall – 1894

Newspaper coverage and witnesses watching him validated his travel through the Midwest. His walk appeared to be legitimate. “He carries a piece of broomstick about eighteen inches long, held by both hands in front of his chest while walking. He has lost but five pounds since leaving New York.” Randall said, “I have never followed any other occupation than pedestrianism.” He claimed that three years earlier he had walked through Africa and Arabia for the London Times and that he held a running record covering 66 miles in ten hours. He said that in 1893 he had wheeled a keg of beer from Philadelphia to Chicago in 23 and a half days.

In March 1894 he was behind schedule in Kansas. In Olathe it was reported, “Mr Randall ate a hearty dinner and after anointing his blistered feet with lubricating oil given to him by the druggist, he started again on his long tramp with the best wishes of a few strangers who had assembled to see the famous pedestrian.” On April 6th, he passed through Albuquerque, New Mexico on a much improved, if not unrealistic pace. In the heat of May from Arizona to Fresno, California, including crossing the Mohave Desert, his pace rocketed to a fraudulent 50 miles-per-day average.

At this point, his story totally changed! He claimed to be an Englishman and instead of starting from New York on January 6th, he said he started that day from Liverpool, England, and he was walking around the world. The wager was to walk around the world in two years and was between two English and American athletic clubs. The newspaper was a bit skeptical. “The tall and lithe Randall claims to be an Englishman although he talks like a native New Yorker.”

A month later, he was telling people in California that he had made the trek from New York in 93 days. The press was highly skeptical of his claims. He tried to get free passage on a steamer bound for Hawaii claiming that he was impoverished due to his wager restrictions. “He failed to impress the steamboat men as much as he did the American press and was told that it costs money to operate a steamer and that people were expected to pay their way when they took passage.” He was left behind. He soon said he changed his plans and would walk northward to Alaska and cross over to Russia. But he finally caught a ride on the steamer Maraposa on Jun 26, 1894.

On July 5, 1894, he arrived in Hawaii. “He carries no arms, no money, no letters of introduction. He is simply a stolid-looking, healthy, young Englishman dressed in leggings, rosy cheeks and a Stanley hat. He next was bound for Sydney, Australia and said he would walk on the ship.” He now said that he started his trek in Liverpool on January 26, 1894 (date changed).

Nothing more was reported about Charles Randall who turned out to be an obvious fraud who prayed on the generosity of others.

C. B. Rendall – 1895

Next is a bizarre tale of a walk around that world that had no coverage during the walk and was clearly fake, but it is a fun tale. Is it possible that C. B. Rendall and Charles Randall were the same person? In 1895, C. B. Rendall, a young former cadet at West Point, New York, claimed he walked around the world in two years and ten days. He set out from Boston stark naked, burning his clothes on the beach. After giving some swimming lessons he obtained a dollar to buy some newspapers which he made into clothes. He then began his walk east to west earning more money for better clothes.

Rendall claimed that once on the west coast, he took a boat to Japan, where he was appointed a lieutenant in the Japanese army so that he might have the right to go with soldiers into China. He served with the army for three months, engaging in 12 different battles where he received several bullet and bayonet wounds while fighting. He walked through India 3,200 miles and was arrested as a suspected spy and detained for two months. In Pakistan, he was robbed and stripped of his coat and shirt by 50 armed thieves.

He made a friend, Sir William Hudson, who provided him an escort of 100 men to walk to Persia (Iran). There, he caused great astonishment because even beggars rode on horseback but this white man walked. “The Shah wished to see such an extraordinary individual and invited him to the Imperial Palace at Teheran.” From there he went through Armenia with an escort of 500 soldiers. The Turks put him in prison as a dangerous character where he sat for four months. From there, his walk through Europe was “child’s play” and he took a steamer from Liverpool back to his starting point in Boston. While away, on three occasions obituary notices for him were published in newspapers. Another account said he walked 1,400 miles in Australia. I guess if you can get it published in a newspaper, it must be true.

Attempts to walk around the world continued. In the early 1800s a popular allegory tale included this statement, “If you could walk all around the world, it would be by putting one foot before the other. Your whole life will be made up of one little moment after another.”

Read all parts:

- Part 1 – Around the World on Foot (1875-1895)

- Part 2 – Around the World on Foot Craze (1894-96)

- Part 3 – Around the World on Foot (1894-1899)

- Part 4 – Around the World on Foot – The Bizarre

- Part 5 – Races Around the World on Foot – Dumitru Dan

- Part 6 – Walking Backwards Around the World

- Part 7 – Dave Kunst – Walk Around the World – 1

- Part 8 – Dave Kunst – Walk Around the World – 2

Sources:

- World Runners Association

- Jan Bondeson, The Lion Boy and Other Medical Curiosities

- Andrew Kippis, A Narrative of the Voyages Round the World: Performed by Captain James Cook

- The Pennsylvania Packet (Philadelphi), Mar 11, 1785

- Atchison Daily Champion (Kansas), Jul 20, 1866

- The Age (Melbourne, Australia), May 13, 1867

- The Sydney Morning Herald (Sydney, Australia), Jun 1, 1867

- The Woodstock Mercury (Woodstock,Vermont), Dec 14, 1849

- Reading Times (Reading,

- Pennsylvania), Apr 24, 1872

- The News Journal (Wilmington, Delaware), Feb 17, 1875

- The Courier and Argus (Dundee, Scotland), Apr 27, 1875

- Leavenworth Daily Commercial (Kansas), Nov 17 27, 1867

- Detroit Free Press (Michigan), May 12, 1868

- The Baltimore Sun (Maryland), Jul 8, 1868

- Sioux City Journal (Iowa), Jul 20, 1870

- The Leavenworth Times, Aug 19, 1876

- The New York Daily, Apr 30, 1878

- Buffalo Morning Express (New York), May 6, 1878, Aug 13, 1893

- Butler Citizen, Apr 23, 1879

- The Saint Paul Globe (Minnesota), Jun 29, 1890

- Spokane Chronicle (Apr 15, 1891)

- Joseph Weekly Gazette (Missouri), Jun 25, 1890

- The Atlanta Constitution, Feb 15, 1891

- The Cambridge Transcript (Vermont), Feb 25, 1891

- The San Francisco Chronicle (California) Jan 20, 1891, Jun 24,26, 1892, Jul 4, 1896

- The Morning Post (London, England), Feb 6, Mar 31, 1891

- The Akron Beacon Journal (Akron, Ohio), Apr 13, May 30, Jul 17, Aug 17, 26, Sep 28, 1891, Jan 6, 1892, Jan 3, 1893, Jul 2, 1958

- Swiss & Times & Italian Herald (Lucerne, Switzerland), May 17, 1891

- The Weekly Marysville Tribune (Ohio), Jun 29 1892

- Reno Gazette-Journal, Jul 18, 1892

- The Summit County Beacon (Akron, Ohio), Aug 31, Oct 12, 1892

- Daily Leader (Davenport, Iowa), Apr 28, 1893

- The Salt Lake Tribune (Utah), Aug 30, 1892, Jul 28, 1894

- The Daily Enquirer (Provo, Utah), Sep 02, 1892

- Omaha Daily Bee, Apr 2, 1893

- The Daily Citizen (Iowa City, Iowa), Apr 25, 1893

- Fort Worth Daily Gazette (Texas), Jan 21, 1893

- Lost Angeles Herald (California), Jan 24, 1894

- The Carroll Sentinel (Iowa), Aug 30, 1893

- Buffalo Courier (New York), Sep 4, 1893

- El Paso Times (Texas), Jan 16, 1894

- The South Bend Tribune (Indiana), Aug 31, 1893

- Springfield Leader and Press (Missouri), Oct 3, 1893

- The Alliance Herald (Fredonia, Kansas), Oct 20,1893

- The Saturday Evening Kansas Commoner (Wichita, Kansas), Oct 26, 1893

- The Coconino Sun (Flagstaff, Arizona), Dec 14, 1893

- The San Francisco Examiner (California), Jan 24, 26 1894

- Buffalo Evening News (New York), Jan 25, 1894

- Clarion-Ledger (Jackson, Mississipp) Mar 24, 1894

- Louis Globe-Democrat (Missouri), Jun 23, 1895

- The Ottawa Daily Republic (Kansas), Sep 20, 1896

- The Olathe Mirror (Kansas), Mar 1, 1894

- The Record-Union (Sacramento, California), Jun 18, 1894

- Hawaii Holomua (Honolulu), Jul 5, 1894

- The Gazette (Montreal, Canada), Dec 27, 1894

- The New York Times (Dec 25, 1894)

- Chicago Tribune (Illinois), Oct 5, 1897, Jan 25, 1904

- Salt Lake Telegram, Aug 23, 1904

- The Daily Free Press and the Times (Independence, Kansas), Jul 7, 1905

- The Daily Gate City (Keokuk, Iowa), Jun 23, 1910

- Republican and Herald (Pottsville, Pennsylvania), Nov 29, 1912

- Louis Gobe-Democrat (Missouri), Jun 4, 1934