Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 33:07 — 37.7MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

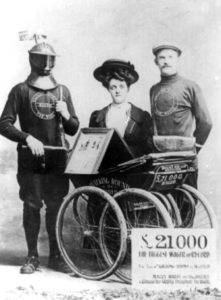

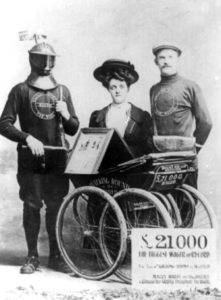

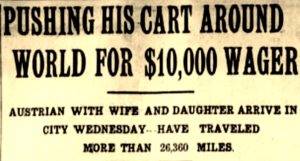

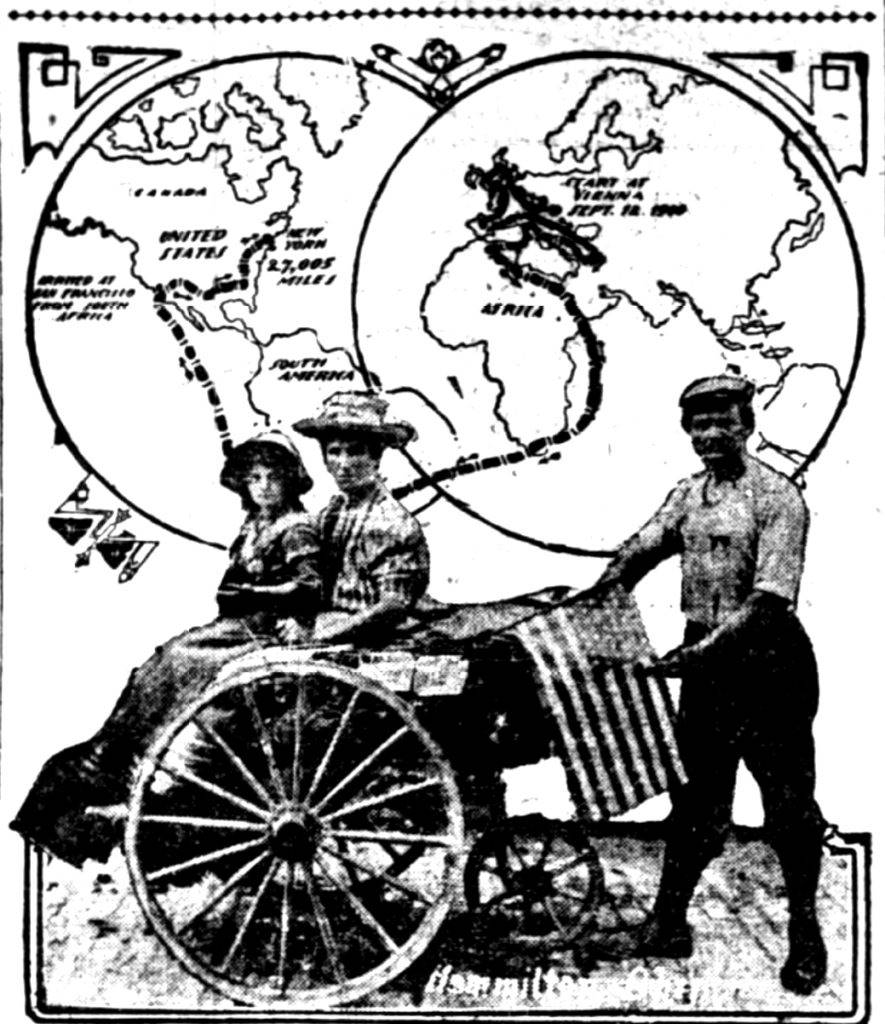

These three stories involved a “masked walker,” an English man who tried to walk around the world in an iron mask. Also, an Austrian man who tried to push his family in a baby carriage around the world. And finally, the “king of the casks”, two Italians who tried to roll a giant barrel around the world. While wager conditions surrounding all three were hoaxes, the extreme walking efforts that took place were genuine. Attention was given worldwide to their efforts. Commenting on one of them, it was written, “He is one of the oddest of the cranks that have started to go around the earth.”

The Masked Walker – 1908

The “man in the iron mask” was a prisoner held in a French prison during the 1600s. Books, theatrical plays, and movies have been produced involving his story. In 1847 Alexander Dumas, author of The Three Musketeers, wrote a fictional tale about the man in the iron mask which captured the imagination of readers in the 19th century.

The “man in the iron mask” was a prisoner held in a French prison during the 1600s. Books, theatrical plays, and movies have been produced involving his story. In 1847 Alexander Dumas, author of The Three Musketeers, wrote a fictional tale about the man in the iron mask which captured the imagination of readers in the 19th century.

Nevertheless, a man in England took up the challenge, and encased his head in a black iron mask “of the fashion of the Middle Ages” and started from London’s Trafalgar Square on January 1, 1908. He pushed a perambulator into a biting wind to begin his ten-year walk around the world, accompanied by an assistant.

The masked walker said, “I at once made up my mind to accept the wager. Upon telling the millionaire the decision I had come to, he at once made arrangement with another well-known American gentleman to accompany me. He is only doing it for the sport.” The masked walker preferred that he be called “the iron mask” and the press wondered how he would find someone willing to marry him without looking at his face. But they guessed if he had a chance of winning $100,000 that there would be plenty of takers. He stated that his future wife must be between 25-30 years old, well-educated, of even temper, and have some knowledge of music.

As he left Trafalgar Square, he waved to the crowd and yelled, “Farewell, see you in ten years.” He then went over London Bridge and down the Old Kent Road with a large crowd following. He said, “I shall sell photographs and pamphlets while on the journey.” The perambulator was filled with them. That first day he was selling them as fast as he could grab the money. He said he needed to touch every county in England and visit Scotland, Ireland, and Wales along with twenty countries. For that first day, he walked all day until 9:30 p.m.

In February 1908, his baby carriage broke down and he bought a new fancy one, with good tires. He was described to be “a sturdy and well set up man, and his conversation was said to betray that he possessed considerable education and culture.”

At Bexhill, England, a typical reaction was described, “Naturally he caused some excitement. Pushing a perambulator, and, of course, wearing the iron mask, is not exactly an ordinary spectacle. An interested crowd followed him wherever he went. Moreover, as one of the conditions is that he must find a wife en route, the feminine element was in great evidence.” His postcards were selling like hot cakes.

By the time he reached Devon, England, he said he had found his wife who was traveling with him in a caravan, but no one was allowed to see her. The masked walker started wearing a black silk mask at night while indoors. Once a chamber maid hid under the masked walker’s bed in an attempt to identify him and claim a reward, but she was caught.

Postcard sales were doing very well, and he had to get a new stock. Witnesses continued to see him walking through the summer of 1908 in England, but the journey “around the world on foot” came to an end at Woburn Sands, England, in late September 1908. For the next several weeks he travelled without walking to various cities putting on lectures, still making people believe he was walking.

He further. admitted that the wager was a tremendous hoax but continued to claim that during his travels he paid his own way by his postcard sales, and supported his caravan, including the horses and attendants. He claimed that he sold a postcard to the King Edward VII and received 200 proposals for marriage.

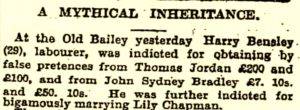

Who was this masked man?

Hensley was brought to trial for felony arson. It was believed that Bensley had actually started a fire to keep warm and accidentally caught the stacks on fire. He was eventually acquitted because his employer gave an excellent character witness for him.

“I began to draw mental pictures of myself passing through life with an iron mask over my face. Gradually they took shape and substance, and I began to evolve a scheme by means of which I could make it a source of profit. I thought of several plans, until at last I hit upon the idea of walking round the world for a bogus wager. Needless to say, a mask was to be the chief feature of the scheme. I spent the remaining weeks of my imprisonment perfecting my plans, writing each detail over and over again on my slate.”

After the iron max hoax was over, Bensley faded away out of the public eye and apparently left the life of a con artist behind. In 1915, while working as an attendant at an asylum, he joined the army as a private. But within a year he was thrown out of the service. During World War II he worked as a bomb checker at an ammunitions factory. Harry Bensley died in 1956 at the age of 79.

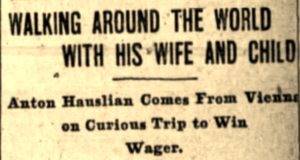

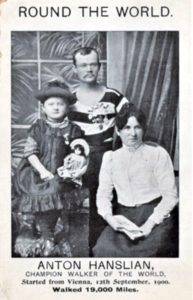

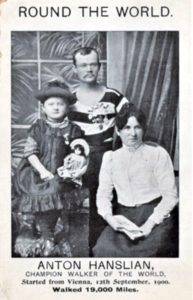

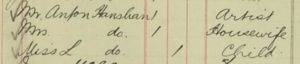

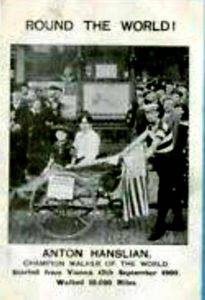

Anton Hanslian – 1900-1907 – Carriage Pusher

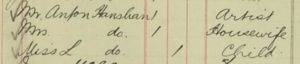

Anton Fredrick Hanslian of Vienna, Austria, was born in 1865. He was an artisan and married Leopoldine Kleimann (1875-1907). They had a daughter, Leopoldine “Polly,” born in 1897. Hanslian claimed that he also was a bareback rider but left the circus ring to earn a living as a long-distance walking. In 1898 he walked from Vienna, Austria to St. Petersburg Russia with a friend, Franz Sklar. During this trip Hanslian picked up the idea to sell postcards along the way to support themselves.

Vienna to Paris – 1900

Walk around Europe – 1900-1902

Hanslian said his motivation for the trip was not only to win the prize, but also for a love of adventure and a desire to see all the countries of Europe as cheap as possible. He needed to start without money, send post cards from each place he visited, and obtain certificates from local officials. To raise money, the Hanslians would sell postcards along the way.

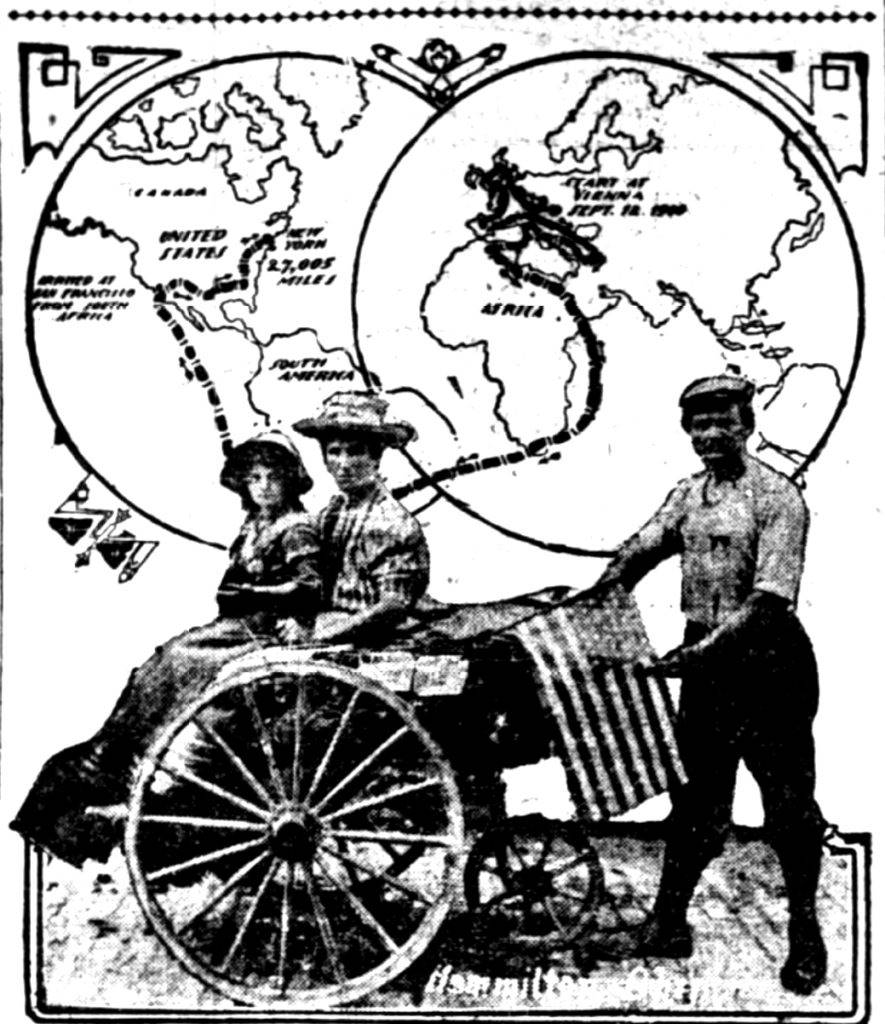

They started from Vienna on September 12, 1900. Hanslian said, “We left Vienna full of hope and joyous anticipation. We had no idea what toils, difficulties and dangers were before us. The weather was good and the people friendly, and the postcards we sold and the lectures I gave in the village inns brought us in a goodly sum of money.”

After nearly two months, they crossed into France. Hanslian knew how to speak a little Czech. Because many French people were not fond of Germans, he pretended that he was Czech and then was treated well. At Calais, France, on the English Channel, they took a ship across to Dover, England. They arrived in London on November 7, 1900. He spent the rest of the year walking and pushing through England, Ireland, and Scotland.

A newspaper in Wales challenged the validity of Hanslian’s wager. “The statement that Anton Hanslian is walking 7,000 miles in order to win a wager is quite devoid of truth. The statement has been made simply for the purposes of advertisement.”

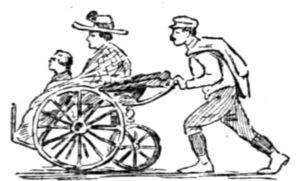

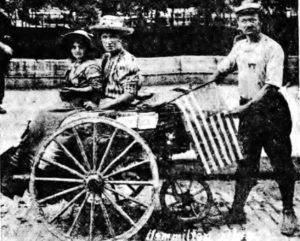

When asked how he managed to live, he produced a bundle of illustrated postcards and replied, “They come to look at me and I sell them these and so live.” About his wife was written, “Tiring through his task may be child’s play to that of his wife who has to sit in the small vehicle all day and often when she rises from it is so cramped that she cannot stand.”

In England, only a few people took them into their homes for free. Instead of depleting their savings, they spend many nights in the open. “We were protected only by our blankets and reserve clothes and by branches of trees against the inclement weather. Our humble meals, too, we took mostly out of doors, and they often consisted of nothing but potatoes, which we baked in a wood fire.”

Leaving Britain, they went to Denmark and later to Sweden. There, his wife became seriously sick again and spent four weeks in a hospital. During that time he worked at his trained profession of a “turner” who turned wood on a lathe. But by the time they left Sweden by ship back to Germany in April 1901, they were out of money. Germany treated them well again and in May 1901, they entered the Baltics in Russia, Finland, and Poland. Near St. Petersburg, Russia, they were put in prison by the police who thought they looked like suspicious characters.

In October and November 1901, they continued to head south through Serbia, Romania, and Bulgaria. The plan was to visit Constantinople, but Turkish officials would not let them enter the country, so they reversed course back toward Hungary in the dead of winter. “We experienced very hard times in the wild Balkan countries. Hardly anything was to be earned by the sale of our pictorial postcards and the days on which we had enough to eat I could count on my fingers. The unfriendly and indeed directly hostile behavior of may people in Bulgaria and Serbia was a source of great alarm to us.” Hanslian had to pull out his revolver often to keep away unpleasant characters that wanted to rob them. The nights were bitterly cold.

They went through France and before entering Spain, a kind person helped Hanslian put an “on foot round Europe” sign on his vehicle in Spanish. The sign was amazingly helpful in getting food and shelter through Spain. They circled north and went through France again. “Near Lyons, I crept together with my wife and child into the public baking oven which stood in the middle of the village and we spent the night there well enough, though next morning we were as black as chimney sweepers. In another place we slept excellently in the churchyard, in the tool hut of the grave digger.”

They reached Geneva, Switzerland on May 21, 1902. Hanslian then pushed the perambulator through Switzerland, back into Germany, and then returned to his home in Vienna, Austria on July 10, 1902, after being away for 22 months and covering about 14,980 miles. (The mileage was exaggerated because he would have had to average about 23 miles per day even with weeks stops because of illness. It was probably closer to 11,000 miles. However, it did appear that Hanslian did walk all the way and did not take rides.) It was said that he won the prize of $2,000. He estimated that he sold more than 50,000 post cards.

At the finish in Vienna, he looked sunburned, thin, and his face lined with deep wrinkles. It was obvious that they had suffered. Leopoldine Hanslian also looked very worn. “But in contrast to her parents, the six-year-old girl looked round-cheeked and bright, though her face and hands were as brown as those of a gypsy child.”

Walk Around the World

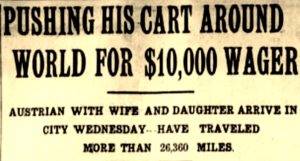

Hanslian wanted to continue. He claimed to accept a new $10,000 deal with a Vienna sporting club to extend his walk to be around the world, pushing the carriage, returning within six years. On October 3, 1902, they set off again heading through Germany, England, and on to America.

America 1902-1903

New Yorkers observed, “Hanslian is on a tour of the world. He pushes before him a wicker-work go-cart in which are seated his wife and child. He stows away the few utensils for camp cooking. The object of his journey is to walk around the world within six years. Hanslian is a wiry fellow 38 years old. His wife is 35 and is the picture of rugged health, as is his little daughter. Hanslian’s costume for his tours is a bicycle suit. The vehicle is a chair much like those in use on boardwalks at seaside resorts”

His plan was to head for San Francisco and then head south through Mexico, Central America, and South America. Then they would steam to Africa, Australia, then to China, and back to Europe through Siberia.

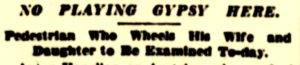

An American commentator wrote, “Inasmuch as the immigration authorities sent him back to Europe because he had not enough money to make it improbable that he would become a public charge, we shall have to consider the wager story a joke. But Hanslian is not easily discouraged, for he is shortly to come back here, and this time he says he will have plenty of money in his pocket.”

They stayed in Great Britain for six months earning money for a return trip. In June 1903 Hanslian was in Wales telling people he was on the way to Liverpool to take a ship to Montevideo, Uruguay. He would then walk through Brazil, Central America, and Mexico. He did not. Just a few weeks later in July, at Sunderland, England, Leopoldine Hanslian gave birth to a daughter, Rosa, who died two months later in London.

North America 1903-1907

Four months later, on November 16, 1903, the Hanslian family again took a steamer across the Atlantic, this time to Quebec City, Canada. Leopoldine Hanslian was pregnant again but still wanted to make the trip.

The Hanslians continued on. At St. Louis, Missouri, they visited the World’s Fair and gave appearances there. But Hanslian soon became very ill. They had to stay many weeks in the city and depleted their funds.

“The appearance of Hanslian is as strange as that of his cart and its load. He wears short knickerbockers and a heavy green sweater. His face is tanned and ruddy and his shoulders rounded from walking. But the muscles protrude from his arms and the calves of his legs like bumps on a log.” Strangely, he now claimed to be able to speak 22 languages. He was still in Kansas in December and it was commented, “The fellow is smart, well-educated, and appears to be an ordinary human freak.”

While heading back near Houston, Leopoldine Hanslian gave birth again on September 1, 1905, and they stopped again. Sadly, either the child died, or they again found a family to care for the infant because it was not with the Hanslians later on. In December they were in Louisiana. “He attracted considerable attention on the streets, while gaping crowds gathered around the strange man and his cart in which were seated his family of two. He has many amusing tales of adventure to relate and like all world travelers has had many close chases with death.”

In March 1906, they were in Mississippi and in May they were in Tennessee. His plan now was to walk to New York City and then take a steamer to Australia, then to China, through Siberia and then home to Vienna. His phony wager changed from six years to seven years.

Hanslian’s tales were becoming more and more embellished. The tiger story moved from Hungary to Africa where he falsely claimed to have been at Cape Town. He also dishonestly said that he had made it all the way to San Francisco and then headed into Mexico on his way back east.

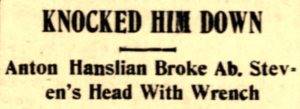

In July 1906, they were in Kentucky, in August in Ohio, and in September in Pennsylvania. Hanslian falsely claimed that he left from San Francisco in December 1905 (when he actually was in Louisiana.) Leopoldine Hanslian commented that she was tired of spending her life traveling in the carriage. She was again pregnant. At Pittsburgh he set up his tent in an amusement park, Luna Park, for a free exhibition to attract people to the new park. He said he earned $1,500 while at Pittsburgh.

At Chambersburg, Pennsylvania in November, they no longer could stay in their tent because of the cold weather and were dependent on finding generous lodging in hotels. Hanslian went in search of a room while his wife and daughter guarded their belongings. Each of the hotels said they were full. He returned to his family and told them the bad news. The crowd there was annoyed because they knew there were actually plenty of rooms. The newspaper eventually let them stay at their office. “This was gladly accepted and a hasty bed was made with the blankets carried by the party. After some food had been eaten, obtained at a restaurant, the mother and daughter went to sleep.”

By the end of November 1906, they arrived in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He told a false tale about his travels in Arizona (where he didn’t go). “For four days the travelers went without water and were only saved from death by a slight rainfall which he caught in an outspread canvas.” Other tall tales included, “Hanslian has 64 medals for fast and long-distance walking, including one of gold which was awarded him for walking from London to Baron, England, a distance of 52 miles in 11 hours. He at one time traveled with Buffalo Bill and Barnum and Bailey as a racer against running horses.” He claimed that since his trek began, that he had worn out 95 pair of shoes and eight suits of clothes.

At the end of the year, 1906, the Hanslians were welcomed into New York City, the same city that tossed them out less than three years earlier. On February 6, 1907, Leopoldine gave birth to her third child while in America, a son, Robert Hanslian (1907-1996) at Jersey City Heights, New Jersey. It is again puzzling that they again gave their infant away. A Lorenz family took him in. It is believed that they intended to come back to claim him, but the Lorenz family eventually adopted him. He was raised in Queens, New York, and lived in New York City for many years.

The Hanslians left America during the Spring of 1907. No, they didn’t go to Australia or China, they went back to England. In June they were at Glasgow, Scotland. Sadly on July 1, 1907, Leopoldine Hanslian died of tuberculosis at Sunderland, England, at the age of 32. Some newspapers stated that she died from a nervous attack caused by being arrested as a spy in China (where she never went). Another paper probably more correctly stated that she died of fatigues of the road.

In May 1908 a newspaper announced that Hanslian won the wager somehow, that he walked 31,250 miles, averaging 12 miles per day, and took 18,000 photographs. (It is estimated that he actually walked about 20,000 miles). “He traversed Europe, America, Australia, and China, and got into trouble during the Russo-Japanese war, narrowly escaping being shot as a spy.” The article stated that he only won half of the $10,000 because his wife had died before returning. Hanslian died that year in 1908. Polly went on to marry a John Pfarter.

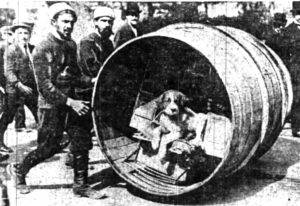

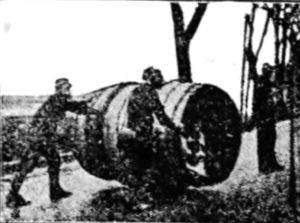

Italians rolling a barrel – 1909 – Kings of the Cask

By 1900, strangely, some ultrawalkers started to roll large and even enormous barrels along the way as they walked. Two Austrians rolled a barrel more than 1,000 miles to the Paris World Exposition in 1900. Others copied their feat.

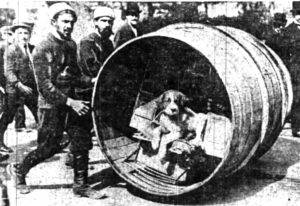

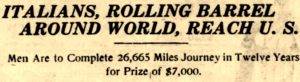

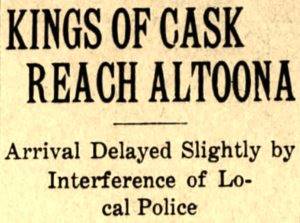

On June 20, 1909, two Italians, Attalio Zanardi (1876-) and Eugenio Vianello (1887-1956), two blacksmiths, age 33 and 22, left St. Mark’s Square in Venice, Italy wheeling a huge custom barrel for a $10,000 prize to roll it around the world in twelve years.

Half of the inside of the barrel was constructed as a kitchen while the other half was used as the seating compartment. The entire barrel could be used as a bed chamber for both walkers. It was made of oak, reinforced with iron hoops. The two believed that they would need to replace it several times during their trip. It was six feet long, four feet high, weighing 480 pounds, but nearly 900 pounds with their contents.

On October 25, 1909 the two rolled into Paris, France. They were escorted out of Paris by a brass band of the Paris Barrel Makers’ union. They next headed to Calais France and then crossed the English Channel to Dover, England.

They arrived in London, England on November 27, 1909, and appeared at the Palace Theatre sharing their experiences thus far. Their rate of progress had averaged about 18 miles per day. They said their toughest stretch of road was going up and over Simplon Pass in Switzerland. “They rolled their barrel to the summit in 36 hours and descended the other side in four. Unfortunately, this rapid rate of progress had the results of damaging their barrel slightly. However, this was soon put right and the rest of their journey across the continent and from Dover to London, was made without further mishap.”

On December 4, 1913, the two arrived at New York City from France, on the French liner, Niagara. They were listed as tourists on the ship manifest. They claimed that they had covered about 24,000 miles during the past three years in Europe, and immediately started rolling toward Yonkers, New York.

The two stopped their barrel rolling for several years. Vianello settled in Detroit, Michigan and served in World War I as a private. He applied for American citizenship in 1920 and was employed as a waiter. Zanardi settled in Chicago where he was a laborer and registered for the World War I draft while living in Chicago in 1918.

In July 1921, Zanardi showed up at Rockford, Illinois rolling the barrel again, with a new partner, Lorenzo Bellegrin. They said they needed to complete their journey by 1924. Nothing more was heard about their trek. Vianello died in 1956.

Others would attempt crazy stunts going around the world, such a walking backwards. A man even tried to circle the globe wearing handcuffs, getting continually arrested when the police thought he was an escaped prisoner.

Stay tuned for the next episode when the story of the first verified walk around the world will be told.

Read all parts:

- Part 1 – Around the World on Foot (1875-1895)

- Part 2 – Around the World on Foot Craze (1894-96)

- Part 3 – Around the World on Foot (1894-1899)

- Part 4 – Around the World on Foot – The Bizarre

- Part 5 – Races Around the World on Foot – Dumitru Dan

- Part 6 – Walking Backwards Around the World

- Part 7 – Dave Kunst – Walk Around the World – 1

- Part 8 – Dave Kunst – Walk Around the World – 2

Sources:

- H. Eisenmann, The Wide World Magazine, “Across Europe in a Perambulator”

- Ed Jefferson, “A man in a iron mask spent most of 1908 pushing a pram around Englend. Nobody knows why.”

- Ken McNaughton, “The Man in the Iron Mask, Harry Bensley”

- Par-Erik Back, “Anton Hanslian – Pushing Wife and Child Around the World”

- The Guardian (London, England), January 2, 1908

- The Observer (London, England), January 5, 1908

- The Indiana Progress (Pennsylvania), Jun 10, 1908

- New York Tribune, Jan 19, 1908

- Rutland Daily Herald (Vermont), Jan 23, 1908

- Des Moines Register (Iowa), Jan 23, 1908

- The Province (Vancouver, Canada), Jan 24, 1908

- The Glamorgan Gazette (Wales), Dec 18, 1908

- The Bury and Norwich Post (England), Dec 2, 1890

- The Jewell County Monitor (Kansas), Aug 1, 1900

- Jackson’s Oxford Journal (England), Nov 24, 1900

- The Brooklyn Citizen (New York), Apr 9, 1903

- The Sun (New York City), Apr 13, 1903

- Muncie Evening Press (Indiana), Apr 15, 1903

- Harrisburg Daily Independent (Pennsylvania), Apr 18, 1903

- New York Tribune, Apr 23, 1903

- The Marion Star (Ohio), Apr 25, 1903

- The Topeka Daily Herald (Kansas), May 23, 1903

- Detroit Free Press (Michigan), May 12, 1904

- The Windsor Star (Canada), May 12, 1904

- The Topeka State Journal (Kansas), Nov 4, 1904

- McPherson Freeman (Kansas), Dec 9, 1904

- Daily Advocate (Victoria, Texas), Apr 11, 1905

- The Jennings Daily Times-Record (Louisiana), Dec 9, 1905

- The Crowley Signal (Louisiana), Dec 16, 1905

- The Times-Democrat (New Orleans, Louisiana), Feb 5, 1906

- The Tennessean (Nashville, Tennessee), Jun 24, 1906

- The Daily Notes (Canonsburg, Pennsylvania), Sep 15, 1906

- The Pittsburgh Press (Pennsylvania), Sep 27, 1906

- Public Opinion (Chambersburg, Pennsylvania), Nov 5, 26, Dec 28, 1906

- The Morning Call (Allentown, Pennsylvania), Nov 21, 1906

- Oakland Tribune (California), Jan 15, 1907

- Louis Globe-Democrat (Missouri), Aug 19, 1907

- The Inter Ocean (Chicago, Illinois), Oct 12, 1907

- The Washington Herald (Washington D.C.), May 31, 1908

- The Ludlow Advertiser (England), Dec 19, 1908

- The Observer (London, England), Nov 28, 1909

- The Cincinnati Enquirer (Ohio), Dec 18, 1909

- The Sedalia Democrat (Missouri), Dec 19, 1909

- The New York Times, Jun 5, 1910

- Pine Bluff Daily Graphic (Arkansas), Jun 21, 1910

- The Daily Times (New Philadelphia, Ohio), Oct 25, 1909

- Pittsburgh Daily Post (Pennsylvania), Dec 6, 1913

- The St. Louis Star and Times (Missouri), Jan 29, 1914

- Passaic Daily News (New Jersey), Jan 30, 1914

- Altoona Times (Pennsylvania), May 1,15, 1914

- Pittsburgh Post-Gazette (Pennsylvania), Jun 1, 1914

- Pittsburgh Daily Post (Pennsylvania), Jun 1, 1914

- The Billings Gazette (Montana), Jul 6, 1921