Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 35:47 — 40.6MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

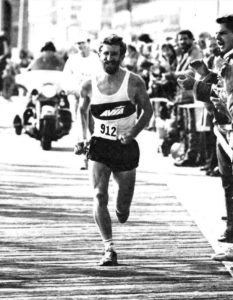

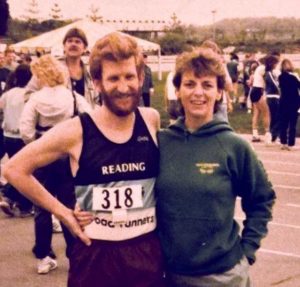

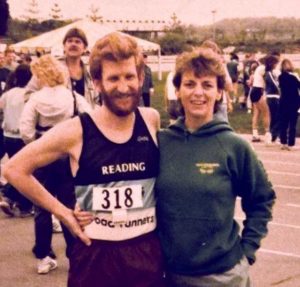

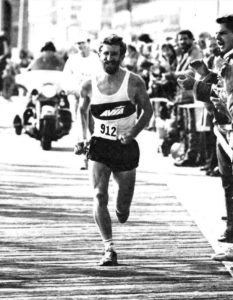

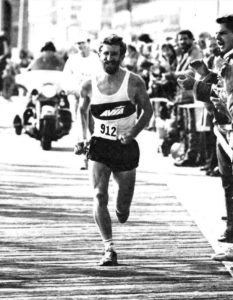

Trayer went from running in the Olympic Marathon Trials to ultrarunning. He was one of the very few elite American ultrarunners of the 1980s who competed against the best runners in the world internationally. He is credited for bringing American ultrarunning to the world stage, and became both feared and greatly respected by runners in the ultrarunners in Europe. He was definitely a runner to watch. In 1987 he was named the Ultrarunner of the year by Ultrarunning Magazine and was honored also in 1987 as the first recipient of the TAC Ted Corbitt Award. He was easy to pick out and known for his bright red hair and beard. At one time he was described as a cross between a leprechaun and Yosemite Sam.

Charles Anthony Trayer was born September 14, 1954 in Richmond, Indiana. His father was Raymond Steiger Trayer (1916-2012), and mother was Dorothy M. Coldren Trayer (1922-1971). His ancestors lived for generations in Pennsylvania.

Charlie’s father, Ray was highly educated with a degree in philosophy and religion. As he studied religions, he decided to join the The Religious Society of Friends, commonly called the “Quakers.” In 1941, Ray married Dorothy of Hershey Pennsylvania. She was employed at a local doctor’s office and studying as a laboratory technician. Ray believed in nonviolence and during the World War II years, the young couple moved to North Carolina where Ray served in a civilian public service camp and Dorothy worked as a secretary at a nearby college.

In 1951, the Trayers moved to Richmond, Indiana, where Ray was employed as the manager of a farm at Earlham College, a private Quaker school. The Trayers lived on the farm, which was stocked with pigs, cattle, horses, and used for teaching agricultural science.

Charlie’s childhood

Charlie was born into the family in 1954, joining his older siblings, Susan, Alex and Tim. Always in a hurry, he arrived six weeks early, and spent the first few weeks of life in an incubator. In 1955 Ray left his position as manager of the farm, taking a teaching position in the college’s school of agricultural science. The Trayers moved to their own 45-acre farm northwest of Richmond. Charlie was raised in the Quaker religion.

When Charlie was about age seven, in 1961, the Trayer family sold their farm and moved to a farm at Hershey, Pennsylvania. Hershey is the home of the famous chocolate company. Milton S. Hershey built his famous company there, and in 1905 and a well-planned city was built there. Living on a farm, Charlie was very active and had a newspaper route, delivering by foot and by bicycle. He worked hard on the farm and had to keep up with the baler on foot. All this contributed to building up his running strength as a child. As a Quaker, meditation also taught him how to focus, be stronger, and to endure. As a child, he went by the name of “Tony Trayer,” using his middle name and he was very active in cub scouts. He switched to use his given name once he started running.

High school years

![]()

![]()

College

Trayer ran his first marathon at the Dixon Marathon in Chester, Pennsylvania in the snow. I said he didn’t know what he was doing, but he won with an amazing time of 2:30:56. His abilities and consistency continued to progress. In 1975, he was co-captain of his college cross country team and had improved to be very competitive, winning at a high level. He placed 29th at the NCAA Division III Cross Country Championships in Boston, Massachusetts.

Post college in Reading, Pennsylvania

After graduating from college in 1976, Trayer moved to Reading, Pennsylvania. He joined local running clubs and began running the prestigious, highly competitive marathons. He ran in the 1977 New York City marathon that was won by Bill Rodgers. Trayer finished in 26th with 2:26:17 and he also placed 78th at the 1978 Boston Marathon with 2:25:40.

In February 1980, he set his life-time personal marathon best at the Mardi Gras Marathon in New Orleans, Louisiana, with 2:20:05. It was strongly wind-aided, but it qualified him for the 1980 Olympic Marathon Trials. Just six days before the Trials, he competed in competitive 10K at nearby Lebanon, Pennsylvania and came away with the win with 33:46.

At the time, Trayer was teaching shop at Oley Valley High School and coached cross country and track. One of has former students was receiving training to be a pilot and needed some hours flying by instruments. He offered to fly Trayer to the Olympic Trials that were held in Niagara Falls, New York. Before landing, they swooped down over the iconic falls for a stunning view he never forgot. Other runners thought he was pretty hot stuff flying in on a private plane. At the Trials he placed 115th out of 192 runners, finishing with 2:29:22.

Trayer explained, “At the Olympic Trials, I reached the 10K mark at my top 10K speed. Bill Rodgers and Frank Shorter are right near me, and it was like they were out for a Sunday stroll. Then they clicked the pace up five or ten seconds faster per mile and they were long gone. I worked so hard just to qualify for the the Olympic Trials. I realized that if I wanted to get to that next level, that I would have to take off another 5, 6, or 7 seconds off of each mile. I knew that it would be nearly impossible for me to do that. So then a friend of mine said there were these ultramarathon, “why don’t you try one of those, so that is what I ended up doing.”

As it turned out, the United States boycotted the 1980 Olympic Games that were held in the Soviet Union.

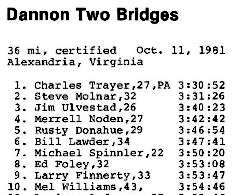

Two Bridges

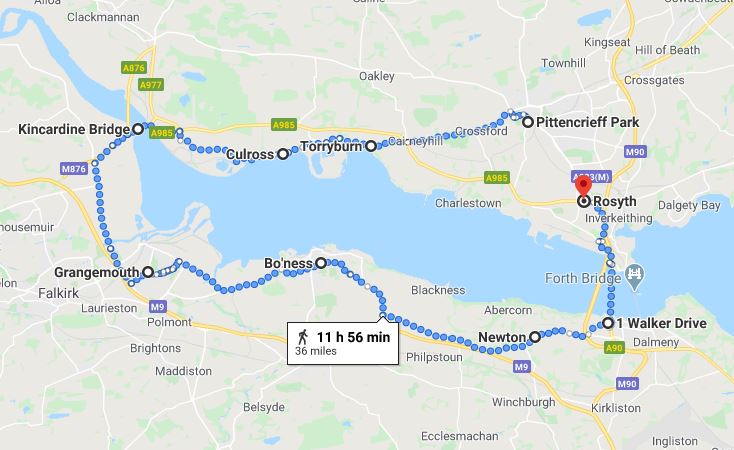

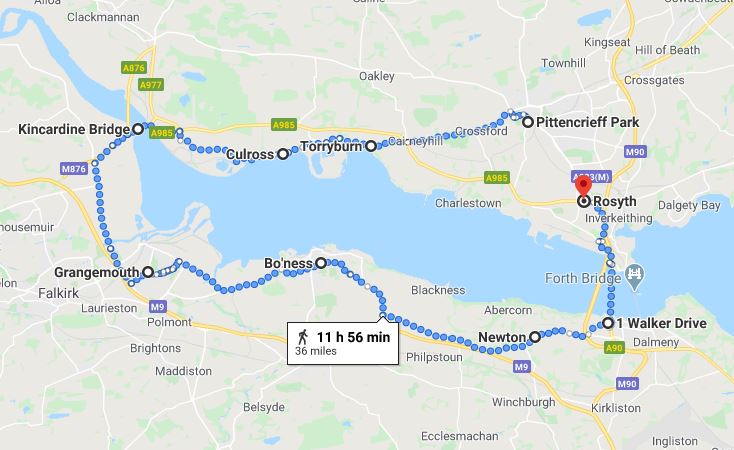

The historic Two Bridges 36-mile road race was Scotland’s most famous ultramarathon. It became a very important part of Trayer’s ultrarunning career, a race he ran nine times. This classic race was established in 1968 and became world-known. Many of the greatest ultrarunners in the world competed there including Don Ritchie, Cavin Woodward, Alastair Wood, and others.

A course description included “After some gentle rolling hills in the first few miles, the course is completely flat between 5 and 23 miles. Then there is a 275-foot hill, and rolling hills all the way to the finish.” Women were not permitted to run in the race until 1983 when Mary Ellen Williams of Maryland won it.

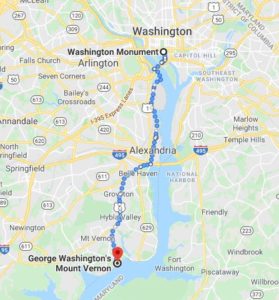

In the United States, other races were patterned after the famous Scottish race. The best known of these races was held in Washington, D.C. It was established by Bob Thurston in 1972 and also called “Two Bridges.” The course was 36 miles and initially ran from the Washington Monument to Mount Vernon and back, crossing over the Potomac River, twice. At the turn-around point, fife and drums played as the runners had to go up 82 steps. This event became one of the oldest modern-day American ultras.

First ultra – 1981 Two Bridges, Washington D.C.

One spectator said for the last three miles Trayer looked like “jogging death” but he held on, winning by only 34 seconds, with 3:30:52, setting a new course record in this tenth edition of the race. He won the trip to race in Scotland. Trayer’s time ranked the best among U.S. times ever for that mileage range. His performance was impressive, and with his sudden appearance in the ultrarunning, he received immediate attention and respect throughout the sport.

Trayer reflected, “I went down there with the idea that I would just run a quick marathon and just see how I could hang on for ten more miles. I went out the way I normally ran. I liked to get out of the front and then settle into my pace and it just worked out pretty good, and that was the beginning of it all for me in ultrarunning.”

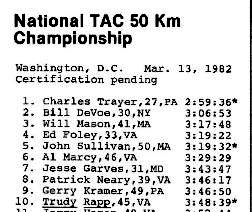

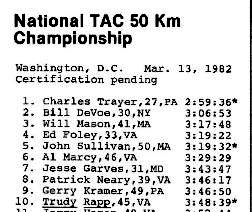

TAC 50K National Championship

He repeated as the 50 km National Champion in 1983 with 3:10:39 at Eisenhower Park in New York City, on a 5 km loop, running in 95 degree weather. Trayer again pulled away from DeVoe, this time at the 40 km mark.

1982 Two Bridges in Scotland

Trayer later said about the race, “It is a great way to see this beautiful country. The small towns and villages we ran through have very old buildings, yet they are very neat and orderly. The views between 26 mile and the finish were fantastic.“

Donna Marie

In 1982 Donna Marie Riegel, Trayer’s future wife, was from Reading, Pennsylvania. She grew up in Italy where her father was in the Air Force. She was a divorced mother of three boys who worked at a drug store. She ran in some short running races with friends and they were just happy to finish before the ambulance that followed the field in the rear. They had noticed Charlie at races, always alone. They invited him to go with them to a race in Philadelphia, and after that became his transportation for various races in the area.

At that time, Trayer was a delivery man for Charles Chips, a snack food company. He also taught wood shop at a high school, coached track, and ran in races during the weekends. He would stop in at the drug store where Donna Marie worked to see her and sell his chips.

During 1983, Trayer ran many marathons and shorter races. He ran the Baltimore Marathon for the fourth time, finishing 5th with 2:32:44 as a tune-up for running a 2:28:34 Boston Marathon a week later. Trayer said, “A leg injury laid me low for about a month. I got in a couple of good weeks of training, 93 and 107, but that won’t do it.” He finished Boston at least ten times.

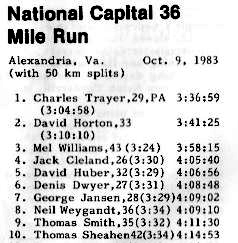

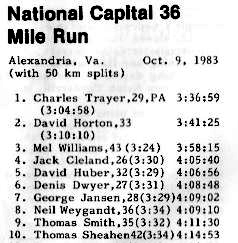

1983 Two Bridges in Washington D.C.

Trayer dominated, took the lead from the start, and built up a lead of six minutes. He said, “I went out really quick, which is what I usually do. I wanted to win this to go back to Scotland.” He reached the marathon mark at 2:34:13. Donna Marie kept up with him on her bike. Because he had such a large lead, she didn’t have to worry about getting into people’s way.

Donna Marie recalled, “On the way back to Old Alexandria, I saw how far out front Charlie was, so I really enjoyed the comfortable ride for the second half, over the bridge, thru the mall, and back to Old Alexandria for the finish.” She rode ahead to the finish, dropped her heavy bike, and could barely stand or walk.

Trayer won in 3:36:59. David Horton, 36, of Lynchburg, Virginia was a distant second with 3:41:25. Horton commented, “His big lead kept me motivated. After a mile and a half, though, I didn’t even see him.”

Donna Marie recalled, “I was on cloud nine. Charlie won and could go to Scotland again. At the awards ceremony he said to me, ‘Since you rode your bike with me, you are now my official support crew, so you will have to go to Scotland with me.’”

A couple weeks later Trayer proposed marriage to Donna Marie while they were digging potatoes at a community garden. They earned money for their wedding by recycling office paper for large businesses – tons of paper. They were married August 4, 1984 before the trip to Scotland. The first part of their honeymoon was to Cape May, New Jersey, because there was a 10K race there. Then they went off to Scotland.

1984 Two Bridges in Scotland

At beautiful Scotland, on race day in August 1984, 115 runners competed. It was a sunny, but breezy day. That year, Trayer was known, and was among the favorites. He again took the lead from the start, chased by two ultrarunning greats, Don Ritchie (1944-2018), the world record holder for 100 miles of 11:30, and Cavin Woodward (1947-2010), former 100-mile world record holder of 11:38:54. At 20 miles Trayer was running stride for stride with Ritchie and the eventual winner, Barry Heath. “Ritchie and Heath stayed together while the American tried several times to get away, only to drop back to the other two.” They reached 30 miles together at 2:56:29. Heath went into the lead at Forth Road Bridge and went on to win. Trayer finished third to Ritchie, just six seconds behind, in 3:34:53.

After the race Ritchie recalled that Trayer commented that he had too much respect for Ritchie to pass him toward the end, but he could have done it. Trayer later explained, “Don was my idol because of all the amazing things he had accomplished. I couldn’t bring myself to pass him.”

Ultimate Runner in Michigan

At this event, The Trayers developed a close and long friendship with Alan Page, who played defensive tackle in the NFL for 15 years. He was one of the few NFL players who went on to run a marathon and later went on to serve as an associate justice on the Minnesota State Supreme Court.

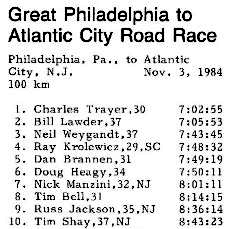

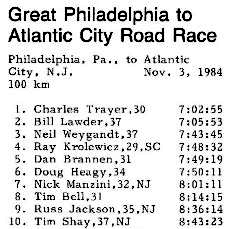

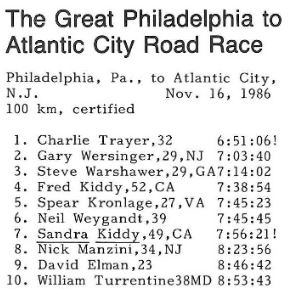

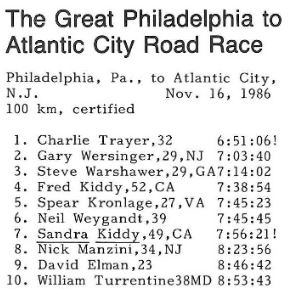

Great Philadelphia to Atlantic City Road Race

Back in 1977, Neil Weygandt, Tom Osler, Ed Dodd, and others, ran from the Liberty Bell in Philadelphia to the boardwalk and Convention Hall at Atlantic City, a distance of nearly 100 km. They tested out the possibility of putting on an annual race similar to England’s famous London to Brighton race. The race became formal in 1980 and won by Weygandt.

During this race, Harry Berkowitz (1940-2008), of New Jersey conducted a coin-finding seminar as they ran along. He said, “It’s best to run on the left, because that’s where people get the bus to Philly, and they’re more likely to drop change getting on the bus than getting off.”

1984 Philadelphia to Atlantic City

Dan Brannen wrote, “Charlie Trayer, perhaps the most undeservedly obscure ultrarunner in the country had little trouble ‘moving’ up to what some consider the ‘real’ ultra distance. He lurched into his characteristically early mad dash from Philadelphia’s City Hall in a pre-dawn, sub-freezing November chill.”

Other runners thought Trayer would crash at the longer distance, but he didn’t slow to more than seven-minute miles until after the 50-mile mark. “Trayer literally tumbled at around 52 miles, his left hamstring finally succumbing to a 10-mile attack of cramps.” He lost his lead, but he soon recovered, and powered on to the win in 7:02:55, with a prize of $500. It was the fastest 100 km time in America that year.

Other Philadelphia to Atlantic City races

100K km World Championships

The International Association of Ultrarunners (IAU) was formed in 1984 and eventually made plans to hold 100 km world championships. These international races became a catalyst for more runners to get into ultrarunning and compete at the 100 km distance.

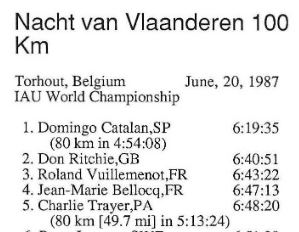

In 1987 the first IAU 100 km World Championship was held in Torhout, Belgium. It did not include national teams and it was run on an uncertified course. Most of the top Americans at the time entered and started the event, including Trayer.

1987 World Challenge – Belgium

The race started in the afternoon and ran through the night in rainy weather. Trayer started fast with the leaders as usual as they moved through the narrow streets of Torhout. By about 15 km, Don Ritchie caught up with the front-running group and later wrote, “We came to a dirt road with many large puddles, so I was very cautious on this stretch, weaving to avoid the puddles in case I got grit into my shoes from splashing through them. By 20 km, I caught Charlie Trayer and Barney Klecker of the USA. I decided to run with them. The checkpoints and refreshment stations were inside sports halls, which we had to run through, and this was quite an experience with all the lights, TV cameras, food, music and lots of cheering people.”

Trayer’s impact on Ultrarunning History

In 2020, looking back, Trayer understood the impact that he had on the history of ultrarunning. “The thing that I gave to ultrarunning, was to get U.S. ultrarunning recognized in Europe. Europe had been ultrarunning for a long time before us. Many of the European ultrarunners were professional runners. They were paid by their government and they had many, many more races over in Europe than we did here in the United States. When I went to run in the first 100K World Championships, I was an amateur runner, working 40 hours a week, and trying to sponsor myself to get to these races because we didn’t have any kind of funding. As an amateur runner, I went over and I came in 5th. That kind of brought us to the forefront, that Americans were able to compete with the Europeans. After doing that several times, then we became respected.”

1987 Two Bridges in Scotland

Ritchie later wrote, “Charlie and I were on our own. However, soon after this I became aware of losing my strength but was able to keep up with Charlie and we passed 20 miles. I found it increasing difficult to stay with him, so I had to ease back and on the steep hill at about 21 miles, I lost a great deal of ground as I shuffled up.”

Trayer added, “I had been running relaxed and not trying to push too hard. At 21 miles, the route goes up a long hill having several levels. By 24 miles, I had pulled away and I was on my own to the finish.”

He reached 25 miles in 2:25:36 and was a minute ahead of Ritchie, and at 30 miles extended his lead to nearly four minutes. Trayer won the iconic race in 3:36:27 and was the first winner outside of the British Isles! That win gave him the confidence that he could run with the top international runners.

He said, “This is definitely one of my favorite events. It’s so well organized that I enjoy the race. Afterwards there is a nice post-race meal, and there is a local pub where the runners can replace any liquids lost during the race. A very enjoyable and exciting day from start to end.”

1987 Ultrarunner of the Year

Trayer’s secrets

When Trayer trained, he ran at a “slow pace” usually around seven minutes per mile, 65-100 miles per week. He trained mostly on the roads which would take its toll over the years on his knees. He would run nearly every day, missing a day or two a month, running all year round. At his prime his only serious injury was plantar fasciitis. He used 10K races and marathons to prepare for longer races.

Trayer explained that leading up to his key races he concentrated more on his diet. “I carried out a rigid depletion and carbo-loading diet. My system was to eat a lot of protein for two days, and then a day during which I took only water. Then I loaded up on carbos for two days.”

Donna Marie explained Charlie’s fueling during races, “From the first time I crewed him, I started mixing a magical concoction from the drug store of a secret mix of powered sucrose, Coke syrup, and a few other bits and bobs for his Energy mix. We found that the secret ingredient was the Coke syrup. Then we were given a huge supply of Exceed powder, and I really had a winning mix. Hands down, my magical concoction provided the most wins for long distances, that and duct tape and Vaseline were ready to send him anywhere.”

Trayer commented on strategy for going out fast. “That’s one of the things that I like to do, go out fast, then just settle into my pace. I’m not that good at running evenly and I usually run a much faster first half. But my goal is to be able to run an even pace throughout.”

He didn’t run very many trail races. “I’m not really very good at trail running. A trail runner needs to be light-footed and I just don’t fit that mold. I’m a forward motion runner. Changing speeds and directions is hard for me. I just do the trail runs as a change of pace. Trail running seemed more about surviving than running” He never ran any 100-mile races.

1989 Stellebosch 100 km in South Africa

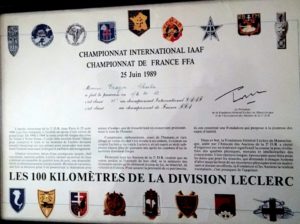

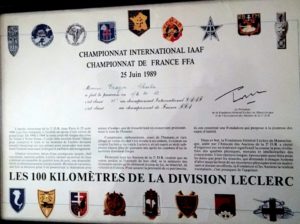

1989 100 km International Championship in France

Trayer was planning on running another race in Europe, but it was cancelled. At the last minute he wanted to instead run in IAFF International Championship, which was held in Paris, France, in late June 1989. Brannen kindly helped for hours one day working to secure a French visa for Trayer so he could go, and he delivered it to him at the airport. Trayer wasn’t able to do his usual race preparation and experienced a lot of stress getting to France, but he tried his best.

The weather was very warm and the race started in the dark at 4 a.m. Once out of the city into the country, the air became cooler but there were some stiff climbs followed by steep descents. As he ran, cyclists were come up blazing fast behind him and towards him causing quite a stir. It turned out that they were training for the Tour de France. There were 129 finishers and Trayer was the top American finisher with a time of 7:40:12, in 31st place.

Trayer had developed great experience running ultras in Europe and had deep admiration for the sport there. He said, “There is more respect, interest, and knowledge of the ultra community over there. There’s much more involvement on the local and the national level with the sport. In America ultrarunners are looked upon as people crazy enough to go beyond the marathon, and in Europe they are looked on as great, as doing something beneficial, not as being crazy.”

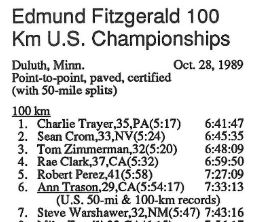

Edmund Fitzgerald 100 km

The stunningly beautiful 62.2-mile course went along the shoreline of Lake Superior from Finland to Brighton Beach, just outside of Duluth. Aid stations were provided every five kilometers.

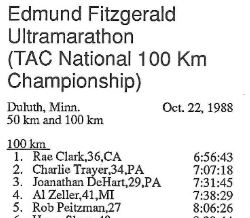

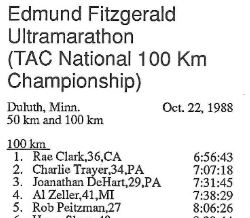

1988 Edmund Fitzgerald

On race day, they both competed well, but Trayer explained, “At 70 km my right hamstring started to tighten. I stopped and rubbed my leg, which helped. At the end it was just a matter of keeping myself going. I knew if it was physically possible for me to finish, I’d finish.” He did, in second place with 7:07:18. Clark won with 6:56:43.

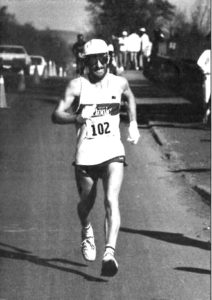

Win at 1989 Edmund Fitzgerald

In 1989, Trayer returned to Edmund Fizgerald and it was again the site of the TAC 100 km National Championship. Three of the 100 km greats of that time competed, Trayer, Tom Zimmerman, and Rae Clark. Gary Cantrell commented, “Certainly the presence of those three in the same race was momentous enough. Between the three of them, they had garnered most of the big performances of the past five years, both domestic and foreign.”

After the mass start, Trayer ran with the lead pack that included Clark and Zimmerman, clocking sub-six-minute miles. On record pace at the 12-mile mark, someone shouted, “That was a 12-mile warmup, now there is only a 50-mile race to go.”

At 50 km, Trayer led the pack, but at 60 km, Zimmerman came to life and “roared into the lead going up a long climb.” But Trayer hung on. Cantrell wrote, “At 70 km Zimmerman had amassed a meager lead of 30 seconds; none the less, he seemed to be in charge. His smooth powerful style stood in marked contrast to Trayer’s typical grimacing red face and choppy stride.” It was now a two-man race.

But Trayer was humble. He later said, “I don’t look for the public acclaim. I’m satisfied to know that I ran my best. The thing that I enjoy most about ultrarunning, the reason I stick to it, is the camaraderie. Once the race is over, we all are good friends and have a good time afterwards. We’re such a close knit group.”

Strolling Jim 40

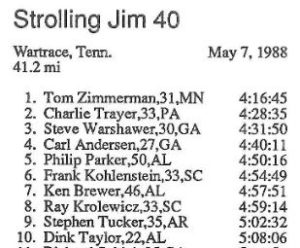

1988 Strolling Jim 40

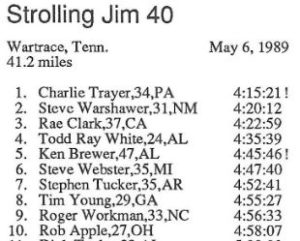

Win at 1989 Strolling Jim 40

Trayer returned to Strolling Jim the next year, 1989, even more determined. Zimmerman couldn’t defend his title because of a stress fracture, so Trayer was the clear favorite. Trayer charged to the front as usual. “Sparks flew from Charlie’s feet as he continued to scorch the road.” He reached 10 miles in 57:20. But by 17 miles Steve Warshawer passed him, starting a classic battle, running sub-six-minute miles.

As they battled, Trayer missed grabbing a jug of water at an unmanned aid station. He accepted a bottle from Warshawer. “Charlie quickly poured this ‘water’ over his head, only to find out that the sticky brown and green liquid now stuck in his hair and beard was actually a ginseng and herb mixture.”

Trayer pulled away and set a new course record by one second in 4:15:27. He said at the finish, “It’s a challenging course because there’s so many rolling hills. There’s very little flat stretches. It’s a very, very tough course.” He tried to win again in 1990 but came up short, finishing 2nd in 4:30:28.

1990 Birmingham 50

They quickly received permission to move the race to a cross country course at a private school. It was a 2.44-mile loop on pavement, dirt, and mud. During the delay of about an hour and a half, the Trayers went back to their motel room and learned about the exciting news that Nelson Mandela would be released the following day from prison in South Africa after 27 years. This brought Trayer great joy and motivated his running performance that day.

But the course was difficult. “It was very flat, but the rain-saturated dirt section portended difficulties a few laps into the race. Back onto pavement streamed the runners, slightly muddied but not slowed.” Trayer took is customary place in front.

“As the lap-count mounted, the mud grew worse and worse. Going around made the mudholes wider, going through made them deeper.” Trayer gained a lead by 15 minutes, then had a rough spell allowing others to close the lead, but he recovered and pulled away again. In the end he won by eleven minutes with 5:38:46. Little did Trayer know that the win would be the last ultra win of his career.

Slowing down in the 1990s

Great Wall of China Race

The race format would include running about 50 miles per day, covering more than 300 miles for a large one million dollar prize package. The winner of each stage would win $50,000. Part of the route had never been open before to foreigners. Trayer increased his training to more than 100-mile weeks with plenty of stair running. The race was first scheduled for August 1990 but sadly, was postponed because of the outbreak of the First Gulf War. It was then rescheduled to April 1991 but the race was cancelled. It was a terrible disappointment to Trayer because running on the wall had been a life’s dream.

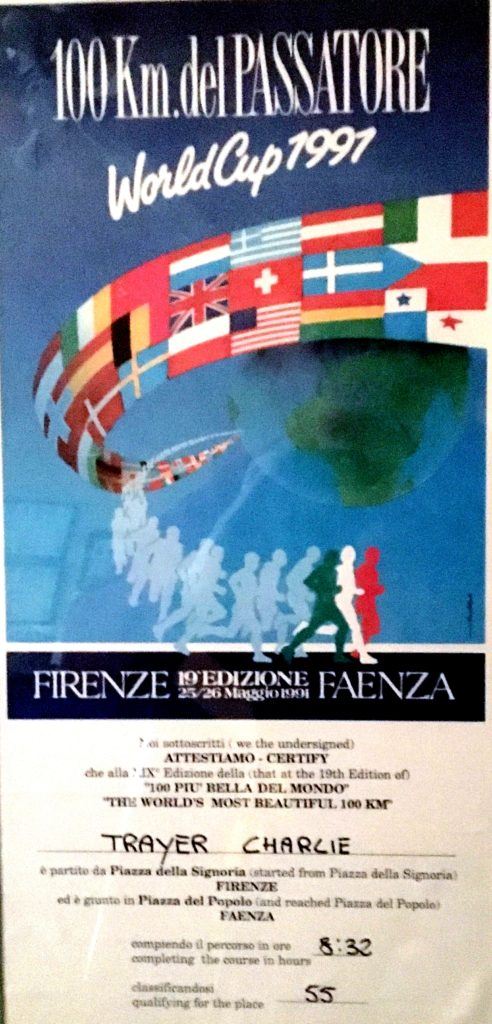

1991 – Italy

That year, for the first time, a full USA national team was allowed to compete. Trayer arrived in Italy only two days before the race, resulting in jet lag.

The race would begin at 4 p.m. and go through the night. Thousands of runners milled around near the start. Ritchie wrote, “The elite runners were arranged in a roped section some 20 meters ahead of the mass of runners about 10 meters ahead of the official start line. Andy Milroy, using his sternest teacher’s voice and assisted by Dan Brannen, of the IAU, managed to persuade us to shuffle back the required distance.”

A mass of humanity pressed forward as the race began. Ritchie recalled, “I was surrounded and found it impossible to run at a pace I wanted. Once we reached the next square, I was able to start moving through and soon reached the loose group at the head of the field.” Then started a steep, steady climb out of Florence for the first 15 km. For most of the runners, dusk would set in at the halfway point. The back of the pack would not finish until late morning. Trayer was a favorite for the American team but ran into trouble early on the mountainous course. Unofficial aid stations sprung up along the way with huge roadside barbecues and neighborhood festivals.

Ritchie described the dangerous scene on the downhill switch-back sections. “Groups of cyclists would come shooting past, sometimes on both sides of me which was disturbing. I also had a close encounter with a car. Later in the darkness, there were sections when one was completely alone and it was quite peaceful.” Rules infractions took place as squads of random cyclists aided many of the top runners.

Trayer struggled badly by 50 km, but Bill Clements slowed to encourage him. It was reported, “They then both ran very gutsy second halves through fatigue and dizzy spells for a fine team finish.” With teamwork like this, the American team was the only team where all the team members finished. Trayer finished in 8:31:26 and Clements in 8:59:30. Trayer finished 55th out of 1,156 finishers.

After competitive Ultrarunning

But life’s challenges made it impossible for him to return to be highly competitive in ultrarunning. Other things were properly more important. He was still always seen running out on the roads in and around his city of Reading, Pennsylvania including to and from work. Be became referred to as the “Forrest Gump of Berks County.”

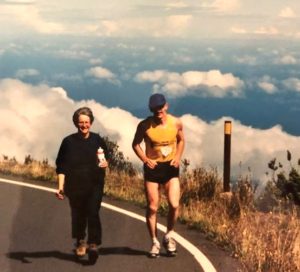

In 1997 Trayer ran the “Run to the Sun” 36-miler up the 10,023-foot Haleakala volcano in Hawaii, finishing 8th overall, clocking the fastest time ever at that time by a runner from the east coast. He called it “the toughest race to train for and run, but the best recovery.” It was especially tough because of the altitude, and he trained using a high altitude simulator.

Trayer ran his last ultra in 1998 at Bull Run 50-miler with a time of 8:26:32. In 1998, he was still having knee problems and a one-mile run even hurt. He had visions of still being able to run classic races like London to Brighton and Comrades in South Africa, but after a family tragedy occurred, involving the loss of a son, the love of running drifted away.

By 2003, Trayer stopped running altogether, “cold turkey.” His running career had lasted 35 years. All of those cobble stone streets in Europe, and carrying tons of recycling, had taken its toll on his knees. Also, he had breathing difficulties due to an irregular heart beat.

But he stayed active in running clubs, organized many races, and developed a love going to flea markets. He became involved with this new close-knit flea market community. One member wrote in 2008, “In my club is a runner who spends most weekends selling this and that at flea markets, and though not out of shape, I imagine no one at the many flea markets would ever guess that he was one of the greatest ultrarunners at one time. The fellow is Charlie Trayer”

Ultrarunning legend and historian Dan Brannen ran with Trayer back in the day. He commented, “He was a down-to-earth, simple, unassuming guy. I envied his approach to the sport: Don’t over-think it, don’t plan a strategy based on who else is in the race, just go right to the front and hammer as hard as you can for as long as you can. Just drive relentlessly right from the start line to the finish line. Don’t consider the course, don’t consider the weather. Every race is the same, whether it’s a mile or a 100 km. Foot racing for him was basic and simple as it should be. You shouldn’t make it complicated.” Charlie Trayer never did.

You can find Charlie on Facebook and Donna Marie on Twitter and Instagram at @us100k

Trayer’s Personal records

- Mile: 4:25

- 3-Mile: 14:25

- 6-Mile: 29:29

- Marathon: 2:20:05

- 50 km: 2:58

- 50 Mile: 5:17

- 100 km: 6:41:47

Sources

- Intelligencer Journal (Lancaster, Pennsylvania), Jun 6, 1940, Apr 25, 1941, Mar 31, 200

- Asheville Citizen-Times (North Carolina), Jan 21, 1947

- The Charlotte News (North Carolina), Jul 6, 1949

- Lancaster New Era (Pennsylvania), Apr 13, 1939. Dec 19, 1941

- Palladium-Item (Richmond, Indiana), Sep 15, 1954, Apr 8, May 1, 1955, Nov 24, 1958, Mar 3, 1960, Jul 5, 1961

- The Daily News (Lebanon, Pennsylvania), Sep 27, Oct 8, 1969, May 6, 1971, Jun 14,29, Oct 27-29, 1971, Jun 14, 1972, Nov 17, 1975, Dec 14, 1978

- Lancaster New Era (Pennsylvania), Nov 1, 1971

- The Morning Call (Allentown, Pennsylvania), Oct 29, 1974

- The Daily Register (Red Bank, New Jersey), Jan 20, 1975

- The Washington Post, October 15, 1979, Oct 10, 1983

- The Baltimore Sun (Maryland), Apr 10, 1983

- Daily News (New York City), Sep 13, 1983

- The Evening Sun (Baltimore, Maryland), Apr, 11, Oct 14, 1983

- Lansing State Journal (Michigan), Jun 26, 1986

- Courier-Post (Camden, New Jersey), Nov 4, 1984, Nov 15, 1987

- The Tennessean (Nashville, Tennessee), Apr 4, May 7, 1989

- Cloud Times (Minnesota), Nov 12, 1989

- Scottish Distance Running History, “Two Bridges”

- Washington Running Club Newsletter, October 1981

- Ultrarunning Magazine, Mar, Jun 1982, Oct, Dec 1983, Jan 1984, Jan 1985, Jan 1986, Jan, Sept, Dec 1987, Dec 1988, Apr, Jul 1989, Jan, Apr, Jul 1990, Feb, Jul 1991, Oct 1999

- Nick Marshall, Ultradistance Summary, 1981, 1982, 1983, 1984, 1985

- Chicago Tribune (Illinois), May 6, 1990

- Honolulu Star-Bulletin (Hawaii), Oct 6, 1997

- The Morning Call (Allentown Pennsylvania), 2001

- Indiana Gazette (Pennsylvania), Sep 10, 2005

- Duluth News Tribune (Minnesota), Sep, 25, 2007

- Nick Marshall records

- Donna Marie Trayer memories and photos

- Charlie Trayer 2020 Interview

- Dan Brannen files and memories

- Andy Milroy memories

- Don Ritchie, The Stubborn Scotsman: World Record Holding Ultra Distance Runner