Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 32:50 — 36.3MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

You can read, listen, or watch

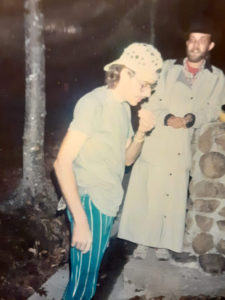

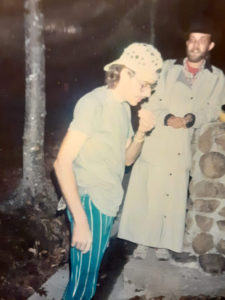

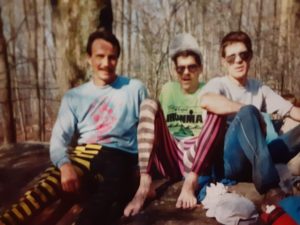

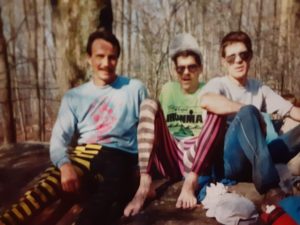

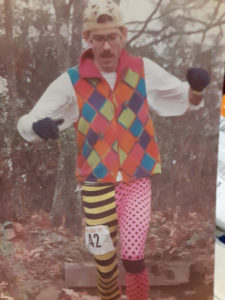

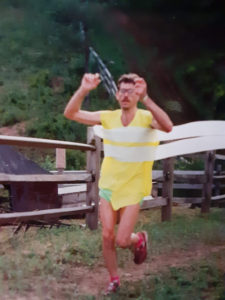

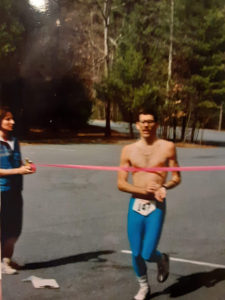

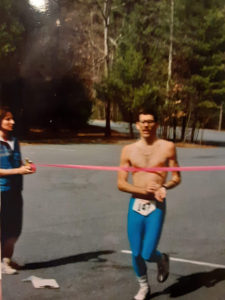

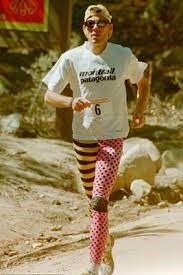

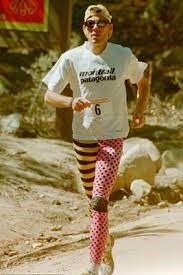

Congratulations to Eric Clifton, originally from North Carolina, now of California, who was inducted into the American Ultrarunning Hall of Fame on November 19, 2021. Clifton was the fastest and most dominating 100-mile trail runner during the 1990s as trail ultras became popular in America. His “go for broke” race strategy was legendary, as he demonstrated to the rapidly expanding sport that amazing speed on trails could be achieved. During his entire career, he has attained more than 60 ultra wins, including 17 of his 31 100-mile finishes. He was known for his colorful running tights and was the original “Jester” of ultrarunning.

Congratulations to Eric Clifton, originally from North Carolina, now of California, who was inducted into the American Ultrarunning Hall of Fame on November 19, 2021. Clifton was the fastest and most dominating 100-mile trail runner during the 1990s as trail ultras became popular in America. His “go for broke” race strategy was legendary, as he demonstrated to the rapidly expanding sport that amazing speed on trails could be achieved. During his entire career, he has attained more than 60 ultra wins, including 17 of his 31 100-mile finishes. He was known for his colorful running tights and was the original “Jester” of ultrarunning.

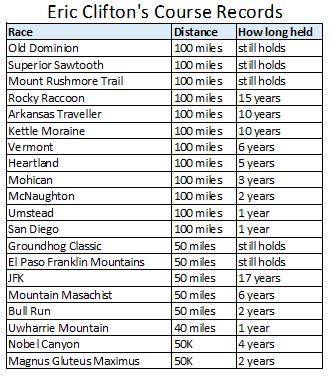

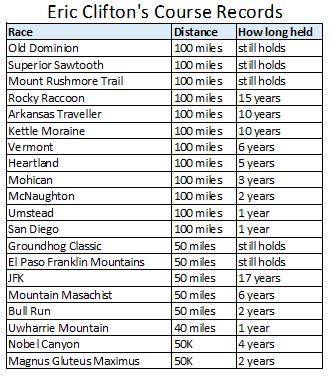

During the 1990s, Clifton had the most overall 100-mile trail wins in the world. He was a prolific ultrarunner and very fast, with more sub-15-hour 100-mile finishes on trails than anyone during that era. He would win by wide margins on hilly trail courses, sometimes by hours. He set more than 20 course records, still holding some of them after three decades.

| Help is needed to continue the Ultrarunning History Podcast and website. Please consider becoming a patron of ultrarunning history. Help to preserve this history by signing up to contribute a few dollars each month through Patreon. Visit https://ultrarunninghistory.com/member |

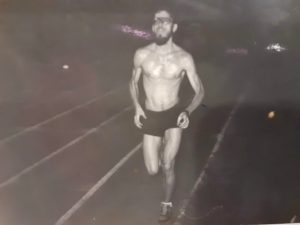

Eric Clifton was born in 1958, Albuquerque, New Mexico but moved to North Carolina when he was young where his father went into the milk business. Eric started distance running as a senior at Northeast Guilford High School in 1976, in North Carolina, where he ran the two-miler. After finished his first race, he swore to himself that he would never run that hard, and that fast for the rest of his life. A friend suggested that he go out for cross-country. Clifton said, “Running cross-country? That sounds like me, I want to do that. I asked, ‘How many miles a day do you guys run?’ He replied, “About ten miles a day.’ OK, I’m out. He scared me away.” Little did Clifton know that he would average running 10 miles a day for much of his future running career.

Serious Running Begins

Clifton went to college at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, where running teams were not fielded. The running boom had not yet reached North Carolina. But in 1977, he started his true running career. As a college freshman, he read an article in the school newspaper about a professor who would be running in the Boston Marathon. He recalled, “I read this article and I was amazed. Wait a minute, there are races that are competitive events for people who aren’t in school doing track or cross-country? It blew my mind.” Within a week he entered his first race, a seven-miler. He had a blast and was hooked on running after that.

Running at Boston became his primary goal. At the time, the qualifying standard for him was 2:50. He ran his first marathon in 3:38. As he kept trying, his finish times went up instead of down. It took him three years before his times dramatically improved. “I finally had a race where I didn’t die. I ran strongly the entire way and did a 2:39. And everybody asked, ‘What did you do?’ I replied, ‘It was what I didn’t do, I didn’t die.’” But by the time he qualified for Boston, he had lost interest and did not run there until many years later.

Triathlons

In 1980, Clifton watched the Ironman on television in its third year and knew that the event was for him. During the ‘80s, Clifton shifted away from running marathons, turned to triathlons and excelled. He ran his first of several Ironmans in 1981.

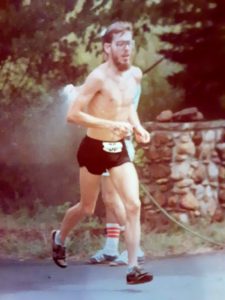

First Ultra – 1982

In 1982, Clifton ran in his first ultra, a 50-mile road race in Wilmington, North Carolina, called “The Lite Ultra” that ran on a four-mile loop. Don Aycock, age 30, originally from Baton Rouge, Louisiana, one of Clifton’s training partners, had subscribed to Ultrarunning Magazine. Clifton recalled, “He told me, ‘Hey, there is this 50-miler in Wilmington, let’s go do that.’ I thought he was a little nuts, but I was doing Ironmans, so I said ‘I’m game.’”

But Clifton first wanted to try to run 50 miles in training, to convince himself that he could do it. They picked a 50-mile bike course and attempted to run it using stores as aid stations. Aycock dropped out after 42 miles, but Clifton continued. At the 50-miler mark, was his wife at that time, Shelby Hayden-Clifton, and his mother. He remembered, “When I ran around the turn, and I saw them 200 yards away, and I knew I was going to finish the 50-miler, I got so emotional and was weepy. That was a really impactful moment for me.”

When he later did the 50-mile race, it was an awful experience. It was held during a tropical storm and very cold. He injured his knee, and it took him months to heal. He finished 8th in 7:25:11, but had no desire to run anymore ultras, because that one hurt so much.

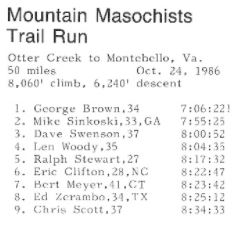

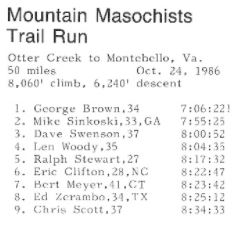

First Trail Ultra – Mountain Masochist 50

Clifton eventually became burned out on triathlons because there was so much cheating going on. He turned to ultra-cycling with Shelby. But after she broke her neck from a crash during “Race Across America,” and had a long recovery, Clifton turned back to running with the encouragement of Aycock. He discovered there was 50-mile trail race in the Blue Ridge Mountains, west of Lynchburg, Virgina, put on by David Horton, called, “Mountain Masochist” in its 4th year. Clifton had limited experience on trails because the trails were few near his home. But he found some, did some training and fell in love with the experience.

He continued ahead of the group until mile 14 when he needed to make a bathroom stop. Like the rookie, he was, he went way off into the woods for a long stop, watching runner after runner go by while he was doing his business.

When he tried to take off to catch up, his legs were dead, and others passed him. At mile 34, in cold rain, at the beginning of the “infamous loop,” a five-mile stretch, the hardest part of the course, he was ready to drop out. But he wanted to at least do the loop before quitting. His crew gave him a soft drink and soon his energy kicked in and he blasted along and finished strong in 6th place, in 8:22:47. “I was astounded, I couldn’t believe it. I was hooked on trail ultras after that.” Clifton would place second the next year and would win in 1990, setting the course record.

First 100-milers

Early in his career, Clifton liked to register for races using funny aliases, like “Jester Wag,” or “Toots AsIGo.” Some serious runners without a sense of humor would be bothered by this comedy. While Clifton was always serious about running, he never “took it seriously” since it was just running.

Learning from his rookie mistakes, Clifton next tried Angeles Crest 100, but again after reaching about mile 75, he dopped out because the climbs ahead intimidated him. He then DNFed his third 100-miler but did not give up trying.

Barkley Marathons

Clifton already knew what a character Cantrell was. He met him for the first time in 1980, at Grandfather Mountain Marathon in North Carolina. Clifton and his wife Shelby had finished the race and were standing where runners entered a track for a finishing lap.

“We saw this blond-haired guy come jogging up and he stopped right at the entrance to the track. He reached into his pocket and pulled out a packet of cigarettes. He took a cigarette, stuck it his mouth, held a lighter, but didn’t use it yet. He stood there, and we asked, ‘Aren’t you going to finish?’ He said, ‘yes, I’m waiting for a woman to come in.’” In those early days, women running marathons were still a rare sight and he knew the next woman finisher would get huge cheers as she ran around the track. “So a girl came running up and he tucked in behind her. He lit his cigarette and started smoking behind the woman. The huge crowd started cheering for her and he was smoking his cigarette, waving, taking in the cheers, but stayed behind her. He knew it was a great way to get accolades.”

At the 1988 Barkley, Clifton flew around the first loop, finishing first in a speedy 5:50. During the second loop he made a critical error missing a short section going to the top of Frozen Head again. Clifton finished that loop in second place but decided to quit.

In 1990, Clifton returned to Barkley. It had been extended to five loops. Clifton, David Horton, and David Drach (1956-2018) finished loop three together in 26:22. Clifton was the first to ever start loop four, but wisely returned after 100 meters. Horton was just waiting for his chance. With only seconds remaining to leave on loop 4, he went out and traveled 150 meters to claim the record for the longest Barkley up to that time. Clifton later tried to measure the 1990 course carefully on a map and thought that one loop was actually 35 miles and the three loops he ran were more than 100 miles.

“When we were doing it for the first few years, the trails were not only unmarked, the trails were not there. We were bushwhacking, finding the books. You could look off to your right see someone 100 yards going down the mountain that way, you could look to your left and see someone 100 yards going down that way. It was wild.”

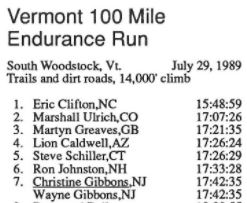

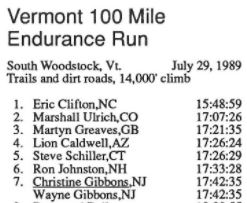

1989 Vermont 100 – First 100-mile Finish and Win

When the start gun was fired, Clifton took off with 114 starters and began to have a great time in the lead. He struggled a bit in the pre-dawn because he didn’t carry a light, but saw lights behind him, giving him confidence that he was going the right way. He kept pushing hard, always running, and just kept waiting to “die” but he didn’t.

Clifton had run six bonus miles because of that blunder and had lost his lead. He caught up with Lion Caldwell and asked him who was ahead, thinking he had lost about 20 places. Caldwell replied, “’There is one guy right in front of us, and then there’s another guy who was just gone.’ I laughed and said that I thought that was me.” Clifton ran hard ahead and within four miles, caught the runner and was back in the lead.

Clifton went on to win, finishing in the daylight in 15:48:59. His first 100-mile finish had been a win with seven bonus miles. In the coming years, he would continue to run well at Vermont 100, winning for four straight years, improving his course record which he held for six years. He still holds the 4th fastest time ever at Vermont with 14:25:00.

Clifton learned a lot from this first 100-mile finish. It truly got him hooked on running 100-milers. “I didn’t realize you could feel great running 100 miles. Every race I did after that, I tried to recapture that experience.”

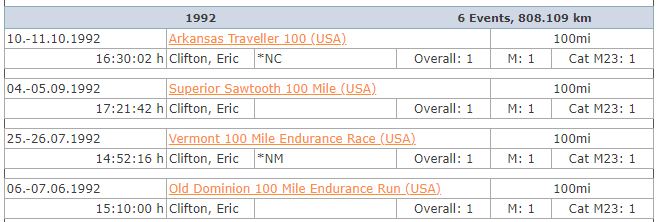

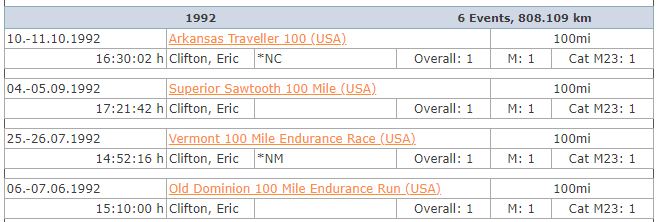

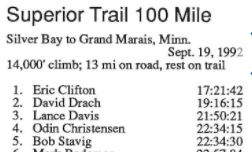

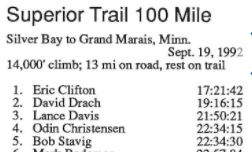

1992 – Four 100-mile Wins – Ultrarunner of the Year

At 1992 Old Dominion 100 in Virginia, it was said that Clifton was running so fast that the race director had difficulty keeping up for a while riding his bike. It was believed the course record was untouchable, but Clifton beat it by seven minutes for at time of 15:10:00 and he still holds that course record nearly 30 years later.

At the 1992 Vermont 100, with 212 starters, it was reported, “Eric Clifton seems to own this course as he successfully defended his title from last year.” He won with a time of 14:52:16.

![]()

![]()

The 1992 Superior Trail 100 was one of the best races of Clifton’s amazing career. He considered it a true trail race, mostly on narrow single-track, with occasional rocky, rooty, and marshy sections.

“

![]()

![]()

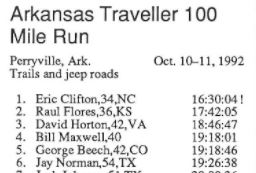

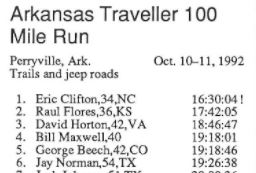

At 1992 Arkansas Traveller 100, Clifton used hard determination to succeed there. He had quit this race the year before at mile 80, due to fatigue. But this year, for the first 41 miles went “all out.” “I was flying. It was like I was dancing on everything, the trails the rocks, the roads. I felt so great. But at mile 42, I started to get nauseous, ten times as bad as at Western States when I dropped out.” He continued on for five miles, hoping it would go away, but it did not.

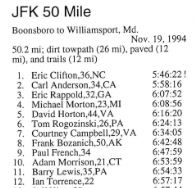

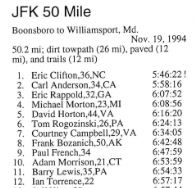

JFK 50

1994 was Clifton’s historic year at JFK 50. He came to the race in very good shape, having run high mileage that year. It really wasn’t a focus race for him that year, but it was on his schedule. The night before the race, Clifton and several others lodged together and read a Washington Post article previewing the race. The long article was mostly about Carl Andersen, coming from California, who the reporter called out as the favorite. He gave past winners Clifton, Horton, and Chris Gibson a small honorable mention. Andersen was indeed an elite ultrarunner and at the time was married to Ann Trason. He and Clifton had dueled for many miles at the 1993 Vermont 100 with Andersen winning in 14:46 after Clifton dropped out, breaking Clifton’s steak of four wins there.

On race morning, the starters included many of the greatest American ultrarunners of the era. Clifton was still stewing over the article. He thought, “’OK, Carl may win, but let’s see what he’s got.’ After the gun went off, I went through the two-mile point in 11:18. I was hauling. When I hit the Appalachian Trail, I was hitting splits that I didn’t even think I could do.”

It was reported, “If anyone was going to beat Clifton this day, they would have to do it by coming from behind, way behind.” He came off the AT (mile 15.7) in 1:52, faster than anyone had run it, with a ten-minute lead over Andersen. Doubters here heard saying, “This guy is going to die a big death on the canal.”

![]()

![]()

Fighting Depression

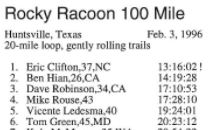

1996 Rocky Raccoon 100

Clifton continued to win at multiple ultra distances during the mid-90s, but he was starting to be challenged by younger elite trail runners that came into the sport gunning for him. At the 1996 Rocky Raccoon 100, both Clifton, age 37, and Ben Hian, age 26, came to break the course record and pushed each other on the root-invested trails.

“Eric Clifton led the rest of the field into the woods, as is his custom, and then ran away from the field for the rest of the race.” Clifton’s first 20-mile loop was a blistering 2:19. His last loop was run in 2:57. The race director observed, “On his last loop in the gathering darkness, he ran by without a flashlight, moving as fast as if it were broad daylight and he were fresh.”

In the end, they both broke the record, but Clifton came out on top, smashing it with his career best 100-miler time of 13:16:02, more than an hour ahead of the much younger Hian.

Clifton said, “The only 100-mile race I ever broke 14 hours in, was because of Ben. I was racing Ben the whole way. I just hammered from step one. I give him full credit for that race, having him back there pushing me. It wasn’t until the last 20-mile lap that I got 20-minutes ahead of him.”

It was reported, “Clifton’s 13:16 is believed to be the fastest 100-mile trail run ever, as well as one of the best 100-mile times on any course in the U.S. in recent years.”

Clifton always set high goals for his races. “Once you accept that something is possible, then you start working for that, and that makes in probable. You have got to think it before you can do it. I think that is one of the things that led to my early success. I think back in the day so many people knew what they couldn’t do. New people coming into the sport today don’t know what they can’t do so they do it and set a whole new level.”

Goal to Win Western States 100

Clifton had moved to Maryland in 1996 and started training with Mike Morton and Courtney Campbell who were young, talented, and very fast ultrarunners. Together they went to California that year to try to break the California streak. Upon arriving, they were surprised to learn that they, east coast runners, were being singled out as the favorites that year.

During the 1996 race, at about mile 53, Clifton was running in fifth with Morton and Campbell ahead of him. Both Morton and Campbell missed a key turn because the single marking there was practically hidden. About a dozen others, not intimately familiar with the course, also went off track. Morton was really fired up about the problem, got back into the race, but later dropped. A Californian again took the win. Clifton, Campbell, and Aycock finished together, well back in 22:57:38. The race that year was a big disappointment, but a very determined Mike Morton finally broke the 20-year California streak by winning Western States the following year in course record time (for the 100-mile version of the course). Clifton started Western States ten times, but could never pull together good race there and only finished twice.

Going Out Fast

Looking back, he now understands that in some races, if he would have stopped for an hour, he probably would have been able to go on, but in his mind that was not doing really well. Once it became more work than play, he would choose to stop.

“What was important to me, was the feeling I got when I was running well. I get a peak performance when I push myself, so why should take the chance, be conservative, pace myself, to get to a finish line, without a peak performance? Once I finally finished a 100-miler, I knew I could, so it wasn’t so much the challenge of getting to the finish line, I wanted to get to the finish line as well as I could.”

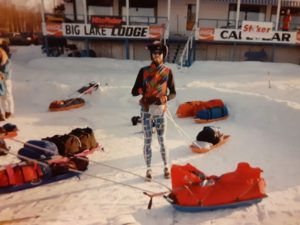

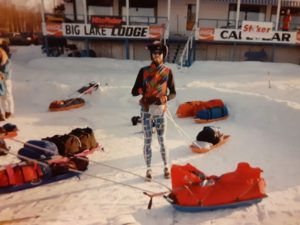

Iditarun

Badwater

After two failed attempts running the blazing hot Badwater Ultramarathon across Death Valley, he won the 1999 race and was featured in the documentary movie, Running on the Sun: The Badwater 135. He won in 27:49:00.

Running in the Later Years

Clifton’s aggressive style was patterned after by many of the next generation of elite trail runners. Hall of Famer, Kevin Setnes wrote: “Clifton has established many course records on trails that seem unimaginable to most of us. He did not set these records by holding back, but by being aggressive and attacking the course. Surely there were times when he would crash and burn from such tactics, but seemingly just as often he would end up winning by a wide margin, in course record time.” Hal Koerner added: “Growing up, I was a great admirer of ultra legend Eric Clifton. He held virtually every 100-mile record for years and was a guy who didn’t believe in walking or hiking during a race.”