Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 27:57 — 33.6MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

You can read, listen, or watch

In 1963, President John F. Kennedy unintentionally played a role that provided the spark to ignite interest for ultrarunning both in America and elsewhere. The door was flung open for all who wanted to challenge themselves. An unexpected 50-mile frenzy swept across America like a raging fire that dominated the newspapers for weeks. Tens of thousands of people attempted to hike 50 miles, both the old and the very young. Virtually unnoticed was a small club 50-mile event hiked by high school boys in Maryland, that eventually became America’s oldest ultra: The JFK 50, founded by Buzz Sawyer.

Kennedy’s Push for Physical Fitness

Fitness Test for Marines

Back in 1908, President Theodore Roosevelt issued an executive order that every Marine captain and lieutenant should be able to hike 50 miles in 20 hours. In 1962 Kennedy discovered this order and asked his Marine Commandant, David M. Shoup (1904-1983), to find out how well his present-day officers could do with the 50-mile test. Shoup made it an order to his Marines. Twenty Marine officers were selected to take the test in mid-February 1963, at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina.

News Article Starts the Frenzy

The Public Starts Hiking 50 Miles

Naïve, untrained, civilians, immediately decided to hit the road without much planning to undertake the challenge in the middle of the cold winter.

Robert F. Kennedy’s 50-mile Hike

After 25 miles, the group was ready to give up. But the press had caught wind of what Kennedy was doing, and a helicopter arrived soon after with photographers and journalists. So, Kennedy set off again. His last aide dropped out by 35 miles, but Kennedy pushed on to the end and reached 50 miles in 17:50, accomplished in a pair of leather Oxford dress shoes.

Everyday People Hike

Two little boys aged 6 and 7, from Florida, set off on their own 50-mile hike. Their hike covered about 18 miles and for food they ate oranges laying on the ground near the road. After about five hours, their mothers returned home from work at a citrus plant and found the boys missing. They searched and finally called the police who recalled seeing boys heading for a youth center. The mothers found the boys on Route 595. One boy received a roadside spanking. The mothers then took the boys to the police station to “teach them a lesson.”

A Newspaper reporter from Baltimore hiked. His reaction was: “The walk was for the birds, only they’re smart enough to fly. Nobody, but nobody should attempt it unless it’s a matter of survival.”

These long-distance 50-mile hikes set the stage for the birth of the JFK 50 in Maryland.

Buzz Sawyer

William Joseph “Buzz” Sawyer Jr. (1928-2019) was born May 16, 1928, in Whitakers, North Carolina. His parents were William J Sawyer Sr. (1904-1980) and Effie (Hamill) Sawyer (1906-1970), with ancestry from North Carolina for generations back to the early 1700s.

When young William was six years old, he contracted rheumatic fever and was seriously ill in bed for six months. But he recovered and thankfully it did not impact his future athletic life. He first became interested in running while attending junior high school in Rocky Mount, North Carolina. He said, “In gym class in those days we had the choice of doing exercises or running cross-country. I chose the latter and I never was sorry for it.”

Running During School Years

Competing After College

But when Sawyer moved to Tulsa, Oklahoma to work for Douglas Aircraft, it started a long period of inactivity. In Tulsa there were no competitions for non-school runners. If he would had stayed in Tulsa, the JFK 50 would never have existed. Luckly for him, and the future JFK 50, he got a break in December 1956 and took a job with Martin Aircraft in Baltimore, Maryland and immediately joined the Baltimore Olympic Club as their top runner, competing in more meets than he did in college.

It was reported, “Sawyer works out on the campus of St. James School near his home in Hagerstown, running a 2-mile course. He rarely runs less than 10 miles a day in all kinds of weather.”

Nationally Ranked Runner

Sawyer was a serious Olympic hopeful for the 1960 Olympics in Rome, Italy, for the 10,000 meters. He said, “If I don’t make that, I would like to keep going and try for a 1964 spot in Toyko.” But in October 1959 he injured an ankle, and he also had a sore leg from running a hard race on pavement. He said, “I was disappointed and the more I watched other people run, the worse I got. Consequently, I began to stay away from meets.” But by January 1960, he had healed and was back into training.

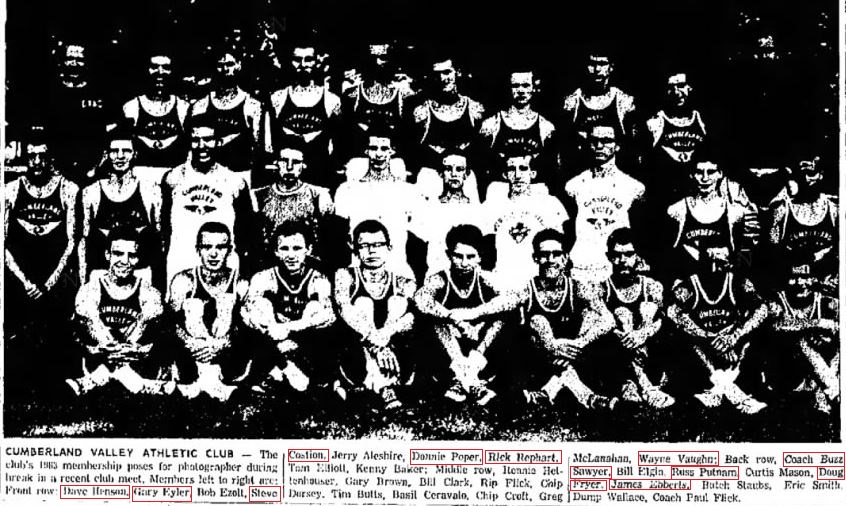

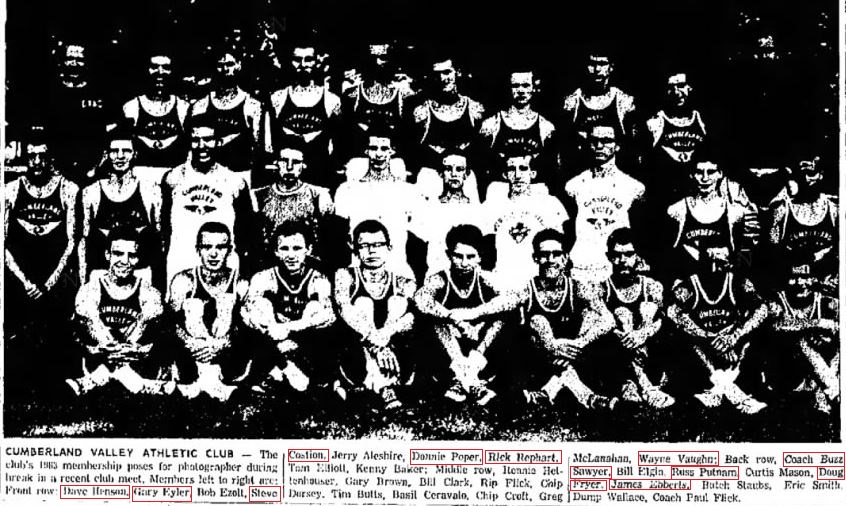

Founding the Cumberland Valley Athletic Club

During the cold weather months, Sawyer ran most his miles indoors at the Hagerstown YMCA, running circles on a tiny balcony track about 15 miles a day. He also conveniently lived at the YMCA and would have feuds with the basketball players that wanted him to close the upper windows as he ran. He soon returned to his winning ways in the indoor 2-mile. He said, “I was more surprised than anyone to win. I hadn’t been able to do any speed work since I injured my leg.”

Injury Struggles

In June 1960, Sawyer traveled to Bakersfield, California in a quest to qualify for an Olympic team berth. But there, his Olympic dreams were dashed away because his painful sciatic nerve condition surfaced again terribly. He was side-lined for months, but by March 1961, he was winning again. He worked for a trucking company as a draftsman and was able to find more time to train.

In 1962, Sawyer proved that his 33 years was not a barrier as he ran the fastest 6-miler recorded in the country for that year, 29:33.6 at John Hopkins University track. He had established himself as the most famous runner in state of Maryland. He coached many talented young runners who achieved greatness. “They learned from Buzz and they gained their passion for the sport from Buzz, and then they went on. Buzz planted seeds and they grew and grew.”

The stage was now set for the birth of the JFK 50.

The Birth of the JFK 50

The date was chosen to be a week before most of the boys who would participate would start the track season at South Hagerstown High School.

Unlike almost all the other hundreds of 50-mile events that year, the young teen-aged club members had been training for the hike. Sawyer, age 34, said that the young club members were “supposed to be in good shape and that’s what I intend to find out. This should be a good test for them.” The finish would be at the private St. James School in Hagerstown, Maryland, with a possible one mile run around the track “just to soften up some of the blisters.” Sawyer said the main reason behind the hike was “a simple matter of conditioning to break up the routine of everyday training.”

This 50-miler in 1963 was a private running club event, not open to the general public and was originally planned to be about 53 miles. One runner recalled, “There was absolutely no race component to it. It was just, ‘Can we do it?’” The CVAC hikers traveled very light, carrying only a supply of band aids and a sandwich or two. Pumps along the C&O Canal towpath were used for water. The plan was to not stop very long, for fear that the boys would stiffen up and wouldn’t get back up. Cars met the group at various places along the way to provide some support.

Sawyer did not advocate any special kind of shoe, just “a comfortable walking shoe.” All eleven hikers (except Sawyer) were high school students. Sawyer was the only one who had any previous long-distance hiking experience, a 25-mile jaunt from Raleigh to Durham, North Carolina many years earlier. Rick Miller, a sophomore in high school, dressed in khaki pants, a button-down shirt, and carried a bag lunch.

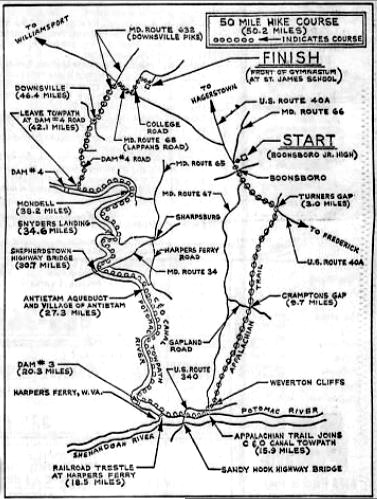

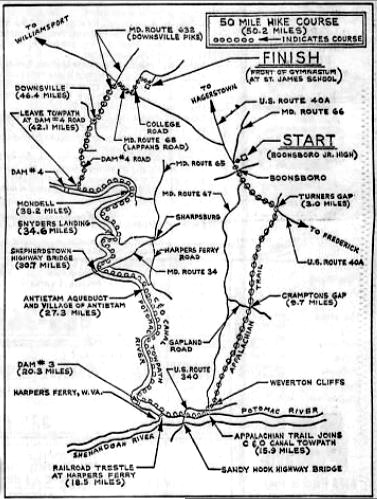

The route for the original hike started at Boonsboro Junior High School, southeast of Hagerstown, Maryland, and went along Route 40 to the Appalachian trail. From there it went to Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, then along the C&O Canal trail to Downsville and then finishing at St. James School in Hagerstown.

The ten boys and Sawyer started at 6 a.m. Three fell behind immediately and decided to take a side route. Sometimes the participants would break into a run for a mile or two, getting ahead of Sawyer and then laid down on the towpath waiting for him to catch up.

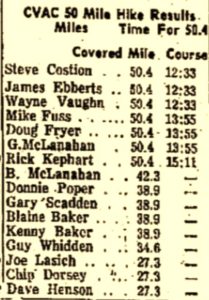

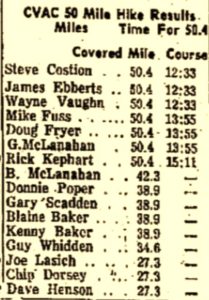

Only three boys finished, together with Sawyer in 13:10. When they arrived at the school, it was dark, so Sawyer called off the mile run around the track. The total distance covered was about 51 miles. Along the way they had spent one hour, sixteen minutes resting and eating. The historic finishers that first year were James Leroy “Big E” Ebberts (1946-), age 16, Steven Michael Costion (1946-), age 16, Richard Edward Miller (1947-), age 16, and Sawyer.

Four others made it to mile 42.1 before dropping out due to fatigue. They were Gary Lynn Eyler (1949-2018), Russell Henry Putnam Jr. (1946-), Donnie Edward Poper (1947-), and David Leslie Henson (1946-2012). Three others took a short cut toward the finish, covered 42.9 miles, but only 27.3 miles on the established course. They were Rick Kephart (1947-), Wayne Vaughn (1948-), and Douglas Paul “Bones” Fryer (1949-). The lead group had spotted them astray on the wrong side of the Potomac River and signaled to them to backtrack across the bridge. Bob Ezolt could not make the hike but several weeks later completed the course in 15:45.

After the finish, Sawyer said there were no plans for any more 50-mile hikes in the near future.

JFK 50 – The Early Years

With Kennedy’s assassination on November 22, 1963, all the momentum for walking and running 50 miles died with him. The mourning country turned its attention to the strife of the tumultuous 1960s. Walks turned into civil rights marches. Other long marches took place in Vietnam. One can only wonder if Kennedy had lived, would have ultrarunning continued to catch on as a national participation sport or was it mainly a one-years passing fad.

1964 JFK 50

At the end of 1964, Sawyer was recognized by the Hagerstown Jaycees as being “Mr. Physical Fitness.” It was reported, “As the smiling recipient of the award ambled forward, he was greeted by a standing ovation which lasted several minutes. Sawyer gazed fondly at the plaque and said, ‘I consider this an honor to myself, but more importantly, a tribute to the work our club has carried on it promoting physical fitness. It was the late President Kennedy who really made us aware of the importance of being physically fit, and we in our club have tried to carry out his ideals.” He then joked that he wasn’t there to recruit anyone to hike 50 miles. After a 22-month layoff from competing, Sawyer was planning on running marathons.

1965 JFK 50

1966 JFK 50

In 1966 the hike was still a club event, but it was opened up to the public to also join in. A couple local runners participated. Instructions included, “Everyone is advised to consume a big breakfast and it is up to the individual when and where he pauses for a snack or a precious drink of water. Last year, some of the club members’ parents set up a refreshment stand at Weverton and there are stores along the route where the hikers can stop. Some carry canteens of water with them.”

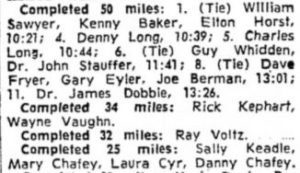

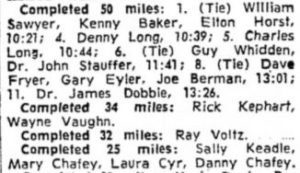

The field of 59, was still dominated by young runners, but it was noted that a 51-year-old, Dr. James J. Dobbie, was in the field that year. Ebberts was away serving in Vietnam so was not there to defend his previous year’s win. Sawyer, Kenny Baker, and Elton Horst lowered the course record, finishing in 10:21. They ran and walked side-by-side nearly the entire way. That year, six girls ran. Three dropped out at 20 miles and the other three made it to mile 25. They were Sally Keadle, Laura Cyr, and Mary Chafey. Only a total of eleven participants finished. Dr. Dobbie was among the finishers, with a time of 13:25.

Not to be out-done, 80 youngsters from nearby LaSalle High School in Cumberland, Maryland also set out on their annual 50-mile hike to celebrate George Washington’s birthday. It was their fourth year; the only other known 50-mile hike still being held that also originated in 1963.

1967 JFK 50

In 1967, the CVAC encouraged more non-club members to enter, but it still was dominated by members. Sawyer wanted to see more of the local running community set their sights on the event to improve their physical fitness. An anonymous donor put up $50 for the first female finisher. There were nineteen starters. But the April 1st race experienced unusual 80-degree temperatures causing some heat exhaustion and many blisters. Vaughn and Ebberts went out at a fast pace, covering the 12.9 mile stretch on the Appalachian Trail in 2:57. “Increased blister activity and the necessity for more frequent water stops by the leaders enabled Sawyer to catch up at mile 43.”

Two women entered that year but didn’t finish, only reaching 9.7 miles. Vaughn, Sawyer, and Ebberts tied with a new record, 10:03. A total of twelve finished. Special medals were awarded to both the oldest and youngest finishers. State Senator, Goodloe Byron participated and finished. Richard Smith, age 21, a student at the University of Maryland, was the first black participant to ever finish the JFK 50. He finished in 14:29:20.

1968 JFK 50

She trained from 50-60 miles each week, seven days a week. When asked why, she replied, “It’s just something I can do. If it wasn’t for Mr. Buzz Sawyer and his excellent coaching, all that I have accomplished and hope to achieve in the near future, would not be possible.” The previous year she had wanted to run the JFK 50, but was sidelined with a knee injury. This year, she was ready.

Aycoth ran the entire JFK 50 with Sawyer, now age 39. With eight miles to go they caught up with Wayne Vaughn and finished together, tied for 2nd place overall with an impressive time of 10:41. She would go on to be the women’s champion every year through 1973. After here finish, Aycoth didn’t hang around at the finish very long because she had a date that evening and her “hair was a mess.” Leo Henry broke the course record with a time of 10:02:12.

He explained that he needed to go to St. James school which was another two miles up the road. They wanted to give him a ride, but he explained that he couldn’t accept it, that he needed to walk. So, they gave him a lantern to carry. He finished in 15:22:25. He then had to call for a ride home. It was the first of his incredible forty-nine JFK 50 finishes. Sadly, his father, Senator Goodloe Byron would pass away from a heart attack at the age of 49, in 1978 while running on the C&O Canal towpath with friends. He finished JFK 50 eight times.

1969 JFK 50

In 1969, the race started to become a big-time race with 153 entrants. The huge field caused a delayed start of 15 minutes because the officials were unprepared for the large number of last-minute entries. James Ebberts and Baxter Berryhill took off at a furious pace. “The pair had timers shaking their watches in disbelief as they sped by check points.” They finished together, crushing the course record with 8:32:04. It was Ebbert’s fifth JFK 50 victory. Donna Aycoth finished again and lowered the women’s course record time to 9:27:31.

Ten-year-old Galen Pryor of Thurmont, Maryland, set the record for the youngest finisher with 13:03:55. A record forty runners finished that year.

JFK 50, into the Future

Entering the 1970s, the JFK 50 was ready to become a serious competition. In 1970 there were 275 starters and in 1971 there were 589 starters with 150 finishers. By 1972 there were about 1,100 starters and the race attracted the most elite ultrarunners in the country. Legendary ultrarunner, Park Barner won in 6:29. In 1973 the starting field was 1,724, the largest ultramarathon ever held in America.

Up to that point the JFK 50 was always held at the end of March or the beginning of April. In 1974 it experienced the worst weather conditions ever for the race. It was 25 degrees at the start and on the Appalachian Trail it sleeted. The trees covered with ice, leaned into the trail and needed to be pushed aside as runners came through. About 83 percent of the field dropped out. After that Sawyer decided to move the race to the Fall for better weather and give people time to train for it during the summer. Sawyer said, “The thing has finally grown to such stature that the Boston Marathon and the JFK are the top distance races in the country.”

The JFK 50 was well established and would live on for decades.

Sources

- Daily Press (Newport News, Virgina), May 28, 1950

- The Times Dispatch (Richmond, Virginia), Dec 3, 1950

- The News and Observer (Raleigh, North Carolina), Nov 5, 1951, Oct 17, 1953

- Rocky Mount Telegram (Rocky Mount, North Carolina), May 11, 1952

- Asheville Citizen-Times (North Carolina), Feb 27, 1954

- The Evening Sun (Baltimore, Mayland), Jan 30, 1957, Nov 22, 1957, Feb 1, 1962, Feb 12, 1963

- The Morning Herald (Hagerstown, Maryland), Mar 20, 1958, May 15,28, Jul 21, 1959, Jan 2, Feb 18, Jun 21,28, 1960, Mar 29, Apr 1, 1963, Apr 6, Dec 8, 1964, Mar 26, 1965, Feb 23, 1966, Feb 8, Apr 1, 1967, Mar 29, Apr 1, 1968, Mar 31, 1969, Nov 10, 2012, May 2, 2019

- The Daily Mail (Hagerstown, Maryland), Mar 24, 1958, Nov 8, 1958, Mar 29, 1963, Apr 3, 1964, Apr 3, 1967, Apr 1, 1974

- The Baltimore Sun (Baltimore, Maryland), Feb 6, Sep 6, 1959, Jun 7, 1962

- Buzz Sawyer Obituary

- Associated Press articles, Feb 6-7 1963

- Life Magazine article, Feb 22, 1963

- Brett and Kate McKay, “Take the TR/JFK 50-Mile Challenge,” May 24, 2017

- The Courier-News (Bridgewater, New Jersey) Feb 15, 1963

- Dayton Daily News, Feb 10, 1963

- Lincoln Journal Star, Feb 10, 1963

- Mike Spinnler – Legacy, A Life Well-Lived, & Paying It Forward | RunChats Ep.49

- 50 Years of Running for the Byrons at JFK 50 Challenge