Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 27:26 — 32.4MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

You can read, listen, or watch

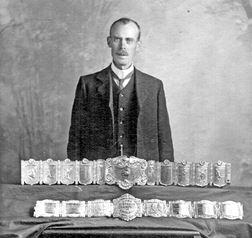

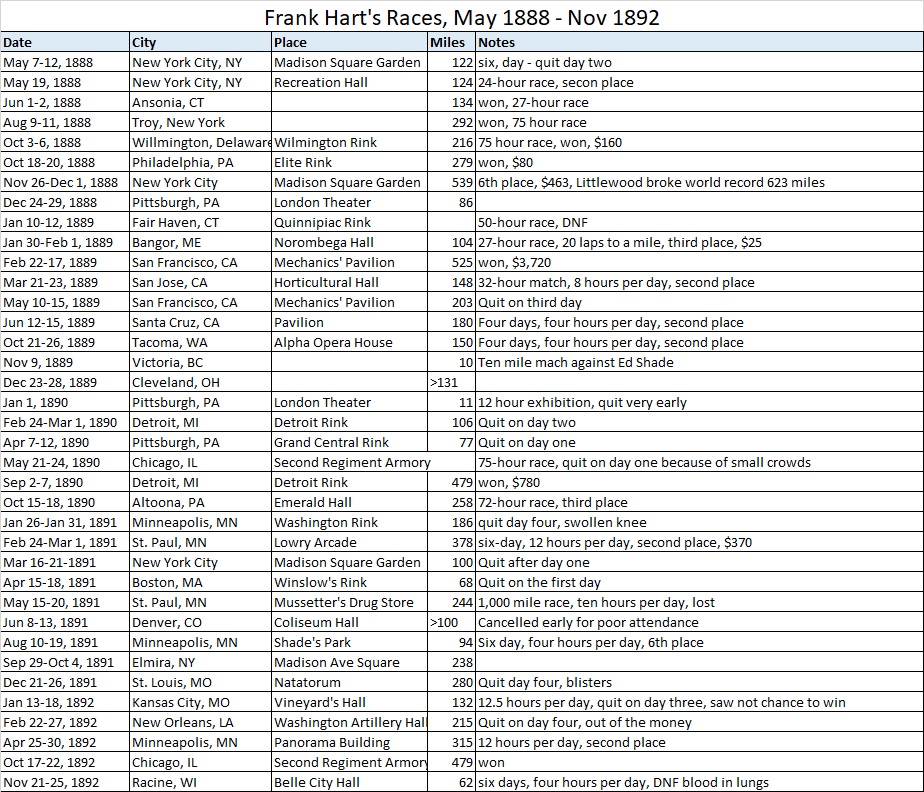

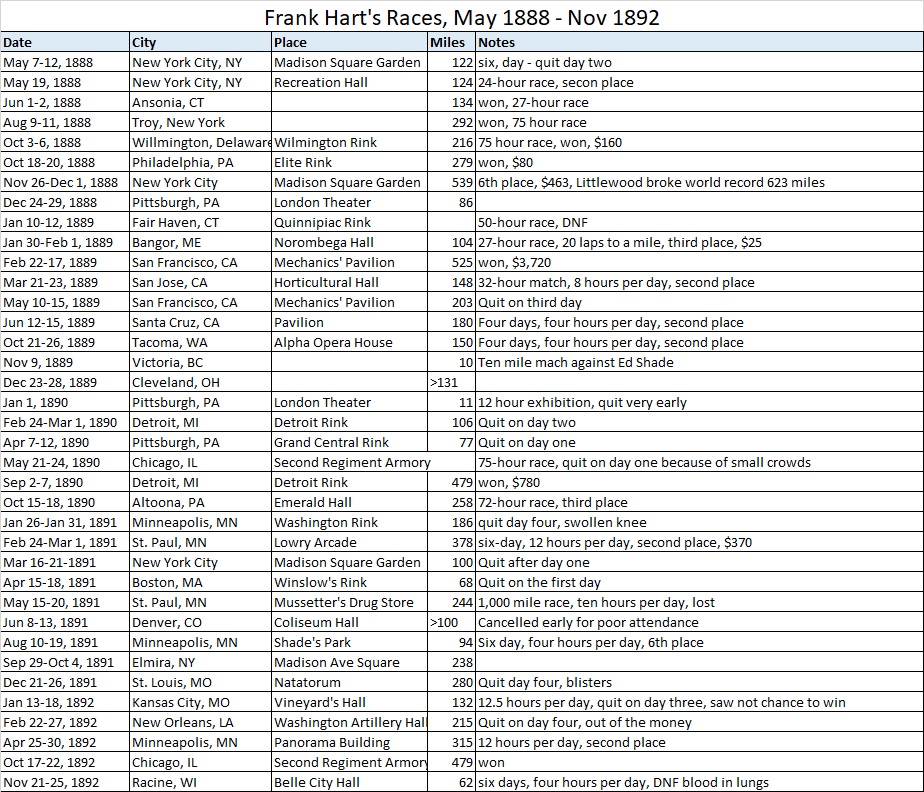

By 1888, Hart had competed in about 30 six-day races in nine years. He had reached 100 miles or more in about 40 races and had so far won at least 30 ultras. Perhaps because of his color, he had not been given enough credit as being a dominant champion during his career. There certainly were some who were better six-day pedestrians, but he was at least in the top-10 of his era.

Racist labels against blacks such has “laziness” were often heaped on him, which bothered him terribly. He worked very hard. How could anyone who competed in six-day races be referred to as lazy? He did have a serious problem with his finances and likely had a gambling addiction. He looked for new ways to make money in the sport, including race organizing and had been criticized for not paying runners fairly. He was so mad at the reaction that he vowed that he was retiring from the sport.

| Get Davy Crockett’s new book, Strange Running Tales: When Ultrarunning was a Reality Show. This book highlights the most bizarre, shocking, funny, and head-scratching true stories that took place in extreme long-distance running, mostly during a 30-year period that began about 1875. |

O’Brien’s Six Day Race

Hart’s retirement did not last long. He entered the next big international six-day race held on May 7, 1888, in Madison Square Garden. For this race, 96 men entered and 44 started. One rejected runner claimed he could go 750 miles.

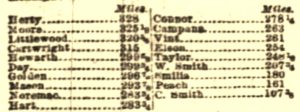

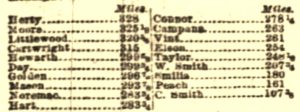

In this race was, George Littlewood (1859-1912) of Sheffield, England, the world record holder for walking 531 miles in six days, reached 100 miles in less than 16 hours. After the first day, Hart was already more than 20 miles behind. On the morning of day two, after running 122 miles, in seventh place, Hart was said to look lazy and quit the race as he was falling in the standings. He realized that he would not finish in the money. Littlewood went on to win with 611 miles.

Throughout 1888, Hart competed in several 75-hour races in New York, Connecticut, Delaware, and Pennsylvania, winning most of them, but earning less than hoped for. Feeling rejected by Boston, he now claimed to be from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Fox Diamond Belt Six Day Race

Hart competed in the most historic six-day race in history, held November 26-December 1, 1888, in Madison Square Garden. There were 100 race entries, but they approved only 40 starters. Richard Kyle Fox (1846-1922), editor and publisher of the sporting publication, The Police Gazette, put it on.

Leading up to the race, Hart trained at the Polo Grounds in Upper Manhattan each day “under the watchful eyes of trainers and admirers” with several other entrants, including Littlewood.

It would be the last six-day race held in the original Madison Square Garden, previously called Gilmore’s Garden, and P.T. Barnum’s Hippodrome, made from an old train depot. The old building would begin to be demolished on August 7, 1889. It was located on the block that currently holds the New York Life Building.

Nearly 10,000 people filled the building for the start with 37 contestants. Through the first night, it became obvious why the building needed to be replaced. “The ring in the center of the garden looked as if it had been swept by a hurricane. Booths were overturned and the floor was flooded with melted snow, which had dropped through the crevices in the roof.” It didn’t seem to bother Littlewood, who covered 77.4 miles in the first 12 hours.

Hart was about 12 miles behind and struggled early. “Several doses of bug juice were taken, and the Haitian youth was wobbly in the legs, and his eyes rolled in a fine frenzy for some hours.” He covered 113 miles on day one, in 11th place. Again, racist comments were made by reporters that he was being lazy. But later he received compliments. “Hart, the colored man, seemed to grow more graceful in his movements as the other stiffened in their limbs.” He reached 204 miles after 48 hours and had moved up to 9th place. Ten men reached 200 miles during the first two days, which had never been accomplished before in one race.

By the beginning of day three, only 18 of the 37 starters were still in the race. Littlewood seemed to be the greatest eater among them. During the morning, he ate eleven lamb chops, washing them down with two large bowls of oatmeal gruel. Littlewood was being handled by Hart’s former trainer, Happy Jack Smith. Hart reached 283 miles after day three. He confined himself to a fast walk instead of trying to run or do a dog trot.

Littlewood took the lead during the early morning of day four, close to world-record pace. During the afternoon of day five, he reached 500 miles. Hart continued to have a good race but was 70 miles behind in seventh place. Smith put together a pacing schedule for Littlewood to make sure that he would break the world record and earn a $1,000 bonus. He needed to average better than four miles per hour.

At 7 a.m. on day six, with 563 miles, Littlewood caught up to the world-record pace. “The contingent of British subjects, which had infested the Garden since the race began, cheered and the sleepers in the back seats awakened and joined in the applause while the band played ‘Rule Britannia.’” Hart was about 80 miles behind but still working hard to get in the money.

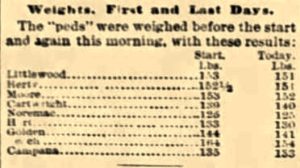

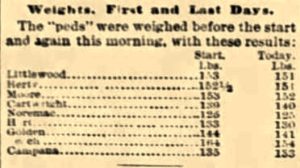

On the final day, Hart passed 500 miles at 10 a.m. Littlewood passed 600 miles at 3 p.m. He went on to break the world record with 623 miles. As with typical six-day races of the era, they were actually scheduled for 142 hours, two hours less than six days, so the crowds could get home before Sunday. Littlewood stopped at 8:07 p.m. and later came out for one more mile at 9:27 p.m. At 10 p.m., they presented him to the crowd as the champion of the world, and then he made a victory lap wearing the diamond belt.

Hart finished in sixth place with 539 miles, running a smart race. He won $463 for his week’s effort. Ten men exceeded 500 miles. Hart had now witnessed the six-day world record broken for the sixth time. They all thought that it would soon be broken again, but it would stand for 96 years until Yiannis Kouros broke it in 1984 with 635 miles.

World International Six-day Race in San Francisco, California

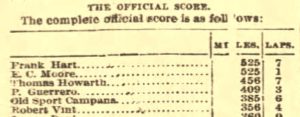

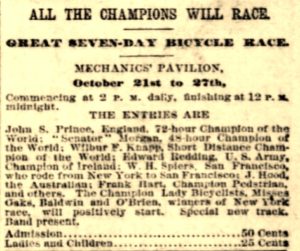

On Feb 6, 1889, Hart left for California on the Cincinnati Express with other runners to take part in a six-day race there. They arrived in San Francisco a week later, greeted by a crowd of fans eager to catch glimpses of them. Frank Hall put A six-day race on in Mechanics’ Pavilion. He hired many people to serve as ushers, bartenders, and scorers. Contestants needed to reach 525 miles to get a share of the gate receipts.

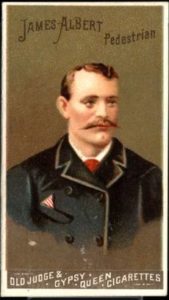

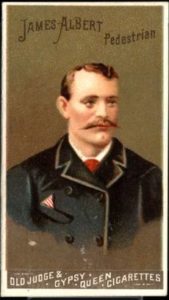

Hart badmouthed the former world record holder James Albert, of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, who chose not to travel to California to compete in the race. He said, “Jim Albert is a coward. He could not run in the company that is in this city now and so he wanted a sure thing of getting $1,000 from Frank Hall before he came here. Because he did not get it, he raises a fuss and tries to injure the race.”

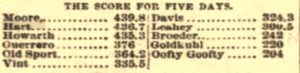

The race began on Thursday, February 21, 1889, at 10 p.m. in the Mechanic’s Pavilion. California six-day races typically did not have a problem racing across Sundays. “So great was the jam of a great crowd gathered at the entrance that the managers decided to throw open the doors two hours ahead of the advertised time. Then there was a frantic rush for the seats of vantage.” 12,000 people were on hand for the start of the 28 runners. The pace was torrid. The bands in the galleries and on the main floor had not finished their first piece before the second mile was reached by the front-runners, including Hart.

As usual, there were complaints about the scoring early on. Hart and others threatened to quit the race if they didn’t score the runners correctly.

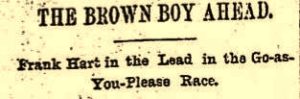

Hart reached 100 miles in 17:40 and then took the lead in the race. He completed 131 miles in 24 hours, which was a Pacific Coast record. “The colored waiters collected in a body and danced a breakdown ‘patting juba’ and using their platters for tambourines.”

Hart reached a very impressive 221 miles after 48 hours. (The world record at the time was 257 miles held by Charles Rowell). He led the procession, and at times singled out Edward C. Moore (1860-1927), of New York, “as a victim for his old trick of dogging following him as the shadow pursues the substance. He seems to have a set purpose of irritating the rival to whom he pays his attention.”

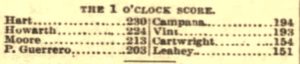

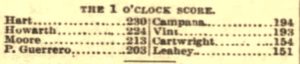

On the second night, “Hart looked tired and dozed as he walked. From time to time, he roused himself, rubbed his eyes and the back of his head, and hastened his speed with springing steps.” At the end of day three, Hart reached 297 miles and was behind Thomas Howarth (1860-1932), of Ratcliffe, England, by three miles.

Band members amused themselves by putting facial decorations such as whiskers on sleeping spectators and then using their instruments to rouse their victims with great laughter. “A wad of blazing paper in close proximity to a sleeper’s legs and a yell of ‘fire’ proved a favorite method until officials put a stop to it with threats of arrest for arson.” They then resorted to pouring ice-cold soda on the sleepers.

The race manager. Hall walked on the track alongside Hart for a while and was accused of coaching him. When Hart dogged Howarth’s pace, things got testy. “Finally, when Howarth was on the verge of madness, he turned on his tormentor and hotly accused him of trying to spike him. Hart replied with equal warmth, and the two fought with their jaws for half a dozen laps. They were about to come to blows at one time, but interference prevented a slogging match, and the cloud of war blew over.” Because of all his dogging, Hart was given the title of “the bloodhound of the sawdust path.”

Hart was very demanding with his trainer, Frank Edwards. He once demanded Malaga grapes and declared he would not run another mile without grapes. “California was able to supply a bunch or two, even at such an unreasonable season, and after eating half a dozen off a bunch, the cranky tramp imagined that he was in fine spirits and spurted for four or five miles at a seven-an-hour clip, eating fried egg sandwiches as he traveled.” He finished day four with 359 miles, just one mile behind Moore. On day five, Hart had a sore knee, and it was bandaged. He reached 436 miles, still within striking distance for the win.

Hart took the lead on the final day. The firm track was taking its toll on him. His trainer said, “The tanbark has been very hard. It was not fine enough, and there was too much on the track. There was no spring to it, no give to it. As a consequence, it used up the men’s feet in a horrible way. We had to put our man’s foot in a mold of plaster of Paris and used everything we could think of to reduce the swelling.” There was a lot of doubt whether Hart or anyone would reach the 525 miles required for prize money. Hart reached 500 miles with 6.5 hours to go.

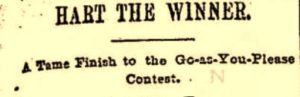

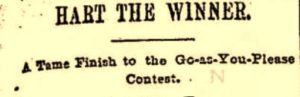

Hart went on to win in a very close race in front of 13,000 people. “The most demonstrative applauders were the representatives of the colored population who were present in force to cheer their champion in his victory.” With fifteen minutes to go, Moore reached 525 miles and quit. Hart, only six laps ahead, also stopped. His win earned him a huge payoff of $3,720. It made his California trip worth it if he could just not squander the money away.

The next day he was asked how he felt. He said, “I’m as hungry as a bear. I have been a professional pedestrian for twelve years and I never suffered so much in my feet and limbs as I did during the match just finished. The track was a poor one. The heat from it caused all the walkers’ feet to be parboiled.” When asked about his plans, he said, “I intend to stay right where I am. California is good enough for me. I am going to open a sports saloon in this city. Californians have treated me well so far, and I think they will in the future.” He quickly opened a saloon at 3 Morton Street, which he called “The Strand.” The street was known as the “sleaziest street in town,” later renamed to “Maiden Lane.”

Another Six-day Race in San Francisco

With the financial success of the February race, another one was quickly scheduled for May 1889. Hart and others trained every morning in downtown San Francisco on an outdoor track, 19 laps to a mile, in a large open space in the back of the old St. Ignatius Building on Market Street. “Later in the day, a few of them would take a run through Golden Gate Park to Ocean Beach and back again, finishing the day’s work by another two hour spin on the track. In this way, the different peds do from 30-50 miles a day.”

There was continued bad blood between Hart and James Albert, who came west to race. Albert had said some nasty things about Hart to the press and Hart vowed to beat him in the upcoming race soundly. Hart would have to eat his words. Albert reached 142 miles in the first 24 hours and won convincingly with 533 miles. Hart quit on the third day, with 203 miles “footsore, sick, and disheartened.”

The San Francisco Chronicle quickly turned against Hart and wrote, “Frank Hart is disgusted with the race. He came here expecting to be the winner. Champion Albert’s appearance at the outset frightened Hart and, becoming weak-hearted, he pulled out of the contest.” There probably was truth to that, because the night after Hart quit, he ran a 10-mile sideshow race with no problem. There were only a few hundred spectators at Albert’s finish. California was quickly losing interest in the six-day races. Hart’s perceived California six-day gold mine was drying up.

Return from California

After participating in some more minor races on the West Coast, earning no significant money, Hart gave up on California. In December 1889, he headed for Cleveland, Ohio, where he did poorly in a six-day race.

He stated plans to head to Australia, a claim he had been making for years. In April 1890, he stated at a six-day race in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, that it would be his last appearance on an American track. “He intends to locate in Australia and has already one or two good pedestrian engagements booked for there.” But as the race began, Hart complained about his feet. He said if he didn’t place in the money, he would cancel his Australian tour, apparently needing the money to get there. He quit after the first day with only 77 miles. His Australian plans were off. He continued to race in the eastern states, but he would always quit early if it looked like he would not win any money or if the crowds were small. His motivation to compete was only to win money.

In September 1890, in Detroit, Michigan, Hart, age 34, finally had another good six-day race, his first in more than 18 months. He covered 100 miles in 17:11 and 123 miles in 24 hours, leading 27 runners. He continued running well, with 218 after 48 hours, and 288 miles after three days. “Hart runs as though the track were India rubber.”

He slowed in the final days, lost the lead at times, but in the end, won with 479 miles, just one further than Moore. He only put in enough effort to reach the 475-mile milestone to qualify for winnings, about $780. For the rest of 1890, he continued to travel, trying mostly unsuccessfully to arrange races that would earn him money.

He competed in another six-day, 12-hours per day race in Jan 1891, at Minneapolis, Minnesota, and was very popular there. “Hart was the center of interest for all the colored people present, of which there were a great number.” With sore feet and a swollen knee, again out of the money, he quit after 48 hours. He liked the attention received and decided to make Minneapolis his home for several years. He was still referred to in the press as “the colored boy,” even though he was 35 years old. They did say he looked much younger than his age, but it was a typical racist label for the era.

First Six-day Race in Madison Square Garden II

In March 1891, the first six-day race was held in the new Madison Square Garden II, located on the same block as the old one that was demolished. It had been open for nearly a year. An outer track, ten laps to a mile, was constructed for the runners along with an inner track to be used by other athletic attractions. The race was highly competitive with 36 starters. After the first day, Hart, about 30 miles behind the leader, reached 100 miles and quit the race. John Hughes went on to win with 558 miles.

The next month, Hart made a rare return to Boston for a six-day, 72-hour race. It was observed, “Frank Hart, the veteran colored pedestrian, did not seem to be in the best condition and acted rather tired.” He was out on the first day. He estimated he had career earnings and wager winnings totaling $100,000 during his 12-year career (valued at $3.2 million today) and that he had hardly anything to show for it. He said that it went out just about as fast as it came in. The four valuable belts that he won during the height of his running career had all been won away from him, something that saddened him greatly.

1,000-mile Race in St. Paul

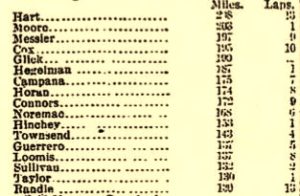

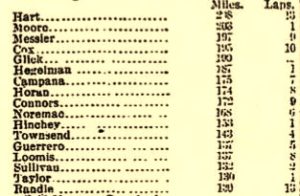

In 1891, Hart, still with a home base in Minnesota, took on a wager for a 1,000-mile race against Henry O. Messier, (1862-1945) of Milwaukee, an experienced six-day runner, for a $1,000 wager. The race would be for ten hours per day and estimated that it would go for 23 days. The only available building in Saint Paul was in a basement under Mussetter’s Drug Store on the Grand Avenue block. They constructed a tiny track, 27 laps to a mile. The first man to reach 1,000 miles would be the winner. Hart was very confident and said he would wager all the money he had that he would cover the distance at least three hours ahead of Messier. They started on May 14, 1891. The race was a huge bust, lost by Hart. After 244 miles, and six days, about 21 miles behind Messier, Hart quit, claiming that his feet were so sore that he could not continue. He lost a bundle of money.

Legacy

At the end of 1891, Hart cared more about his legacy. He embellished stories for the press. He claimed that he used to be a steel engraver that worked in the National steel engraving bureau during President Ulysses S. Grant’s first administration (1869-1873). That was likely fictional because he was a grocery clerk in Boston during that time. He also stated that he had been in more six-day, go-as-you-please races (25) than any other man living. Nobody at the time kept track. George Noremac, Samuel Day, and probably a few others had him beaten by a long margin. He also claimed that he broke the six-day world record twice, but only did it once.

St. Louis Six-Day Race

At a six-day race held in St. Louis, Missouri, Dec 21-26, 1891, Hart’s wife was mentioned as attending a race for the first time. “Hart, the colored boy, is the freshest man on the track, but he is notoriously lazy. His pretty wife sits up in the balcony all day long watching him.” It is possible that the lady was indeed his wife, who came to visit him, sharing some news about his family.

Hart ran hard in this race, trying to prove he still had championship ability. “Hart is surprising his most ardent admirers. He is one of the most decidedly dangerous men in the race, and if he only keeps up courage and avoids becoming lazy, he will surely finish near the top of the list.” He reached 110 miles on the first day. After 280 miles, on day four while in second place, he quit because of blistered feet.

Hart’s Son Becomes a Runner

Hart had some contact with his family. He learned that his son, Frank S. Hart, age 14, had taken part in running races. This was true, later in 1894, a mention was made in the Boston Globe that Frank Jr. won a two-mile foot race that was part of a massive picnic of 2,500 “colored people” held at Highland Lake Grove, south of Boston. The article confirmed he was the “son of the walker.”

Quitting Races Early

In 1892, at the age of 35, Hart seemed to change his racing strategy. Instead of going out hard to win at all costs, he had a more patient attitude. At a six-day race in Kansas City, it was written, “Frank Hart, the colored champion, glides along steadily at an easy dog trot. He says it is not his style of a race exactly, but he will be around in the vicinity of the leaders at the finish.” His old attitude came back when he dropped out at 132 miles because he saw no chance to win.

Observers felt that Hart was “going downhill” as a runner and he indeed had a string of six races where he had quit early. It was speculated, “These long walks not only bring physical wreck but frequently permanent mental disorder.” His pattern of quitting before the six days ended continued in New Orleans in February 1892 when he quit with 215 miles “probably finding that the task of obtaining a position in the race was too severe for the reward in sight.” It had been more than a year since he had finished a six-day race all the way to the end. In most of those races, he could later find the strength to earn $25 by racing in a side-show 10-miler while the rest of the six-day runners continued plodding along. Quitting early was his new reputation.

In April 1892, Hart finally finished a six-day, 12 hours per day, heel-toe walking race to the end, in his adopted hometown of Minneapolis. During the race, he did a little “trash-talking” and said that Willard Alonzo Hoagland (1862-1936) of Auburn, New York, was not as fast as people had been saying he was. This bugged Hoagland, and he had the last laugh, winning the race with 315 miles, five miles ahead of Hart. A rumor circulated that Hart had gone insane after the race finished. But the next day he was seen on the streets, laughed, and said, “Well, I haven’t reached that stage yet.”

When pedestrians were offended by another, they typically would issue a challenge for a duel, not with pistols, but with their feet. Hoagland issued a challenge to Hart for a ten-mile heel-toe walking race and would give Hart a half-mile head-start. Both deposited $100 each into a bank to accept the duel. As with most of these duels, it never took place.

On May 16-21, 1892, Hart competed in a six-day race at the Jackson Street Rink in Saint Paul, Minnesota. On the evening of the fourth day, a pretty, blonde-haired woman, named Eva, came in and issued a challenge to run against professional pedestrian Aggie Harvey and any other women in an exhibition race. The side-show race was arranged, and the amateur beat Harvey by a lap. Harvey wanted a rematch, so the next evening, it was repeated, and Eva lost by three laps in front of a crowd of 500 spectators. “Eva went up to Frank Hart to explain that her corset had been laced too lightly and that she could not run well, when Hart detecting something ‘mannish’ in Eva’s manner, made a grab for the wig and taking it off, exposed a head of hair which only a man could wear.” She admitted she was a man. It was discovered that he was a porter in a nearby hotel. “The makeup was perfect, and the young man carried himself like a real woman, carrying on a handkerchief flirtation with some of the male spectators in the most approved style, and fooling even the best of them.” Hart finished with 329 miles, in third place.

The Battery D Six-Day Race in Chicago

After five months away from racing, Hart appeared at a five-day race in Chicago, Illinois on October 18, 1892, at the Battery D Armory with 18 starters on a small track, sixteen laps to a mile. Hart, age 38, was not washed up yet. He reached 128 miles on the first day and 199 miles in 48 hours. He came away with his first win in over two years, reaching 479 miles. But the race was a failure among the spectators. By mid-race, only 200 people watched at any one time.

Health Scare in Wisconsin

A month later, in November 1892, he took part in a six-day, four hours per day race in Racine, Wisconsin. An alarming report was issued, “Hart went to pieces on the track last evening and his career as a pedestrian is no doubt closed. He was taking with hemorrhage of the lungs.” After only 62 miles, he was vomiting up large clots of blood in front of hundreds of people. He was able to board a train for Chicago to get treatment. Newspapers across the country were reporting that “he will never be seen on the track again.” Rumors spread that he was near death in a Chicago hospital, but then his friend reported he was going to race the following month in St. Louis, Missouri.

Frank Hart Series

- Part 1: First Black Ultrarunning Star

- Part 2: World Record Holder

- Part 3: Facing Racial Hatred

- Part 4: Former Champion

- Part 5: Declining Running Career

- Part 6: Final Years

Sources:

- The Meriden Daily Journal (Connecticut), Apr 2, 1888

- The Santa Fe New Mexican (New Mexico), Apr 19, 1888

- New York Times (New York), May 6, 1888

- The Evening World (New York, New York), May 7, Nov 23, 27-30, 1888, Feb 6, 1889

- The Waterbury Democrat (Connecticut), Jun 4, 1889

- The Brooklyn Citizen (New York), Nov 26, 1888, Mar 1, 1891

- The Kansas City Star (Missouri), Nov 30, 1888

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Dec 2, 1888, Apr 14, 1891

- Lancaster Daily Intelligencer (Pennsylvania), Feb 7, 1889

- The San Francisco Examiner (California), Feb 22-28, Mar 1, 11, Apr 28, May 10-16, 1889

- San Francisco Chronicle (California), Feb 28, May 14, 16, 1889

- The Los Angeles Times (California), Oct 27, 1889

- Pittsburgh Post-Gazette (Pennsylvania), Dec 18, 1889

- Pittsburgh Dispatch (Pennsylvania), Feb 16, Mar 28, 1890

- Pittsburgh Press (Pennsylvania), Apr 7, 1890

- Detroit Free Press (Michigan), Sep 2-8, 1890

- Altoona Times (Pennsylvania), Oct 15-20, 1890

- The St. Paul Globe (Minnesota), Mar 2, 1891, May 7, 1891

- The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (New York), Mar 9, 1891

- La Plata Home Press (Missouri), May 29, 1891

- Star Tribune (Minneapolis, Minnesota), May 15, 1891

- Star-Gazette (Elmira, New York), Oct 2-3, 1891

- Louis Post-Dispatch (Missouri), Dec 13, 22, 1891, Dec 3, 21-26 1892, May 28, 1895

- The Kansas City Times (Missouri), Jan 15, 1892

- The Times-Democrat (New Orleans, Louisiana), Feb 26, 1892

- The Times-Picayune (New Orleans, Louisiana), Feb 25, 1892

- The Inter Ocean (Chicago, Illinois), Oct 18-19, 1892, Aug 4, 1894

- Journal Times (Racine, Wisconsin), Nov 25, 1892