Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 24:43 — 28.5MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

You can read, listen, or watch

| Get Davy Crockett’s new book, Running 100 Miles: A History (1729-1960) This definitive history of the 100-mile races presents the rich history of many, both men and women, who achieved 100 miles on foot. Part one of this history includes tales of the trail-blazing British, the amazing Tarahumara of Mexico, and the brash Americans. Many of the early legendary, but forgotten, 100-miler runners are highlighted. |

St. Louis Six-Day Race

Hart recovered and showed up in St. Louis for Professor Clark’s Six-day Tournament held on December 19-24, 1892, at the Natatorium (swimming and gymnasium hall). People were astonished to see him a week before the race. “Frank Hart, the famous colored ped arrived in the city yesterday, a living contradiction to the rumors that had been circulated about his ill health. He denies that he coughed up a lung and part of his liver.” He trained with other competitors at the Natatorium and was seen reeling off mile after mile. He indeed started the race and looked good in the field of fifteen runners. “A new lease of life appears to have been meted out to the old-time colored pedestrian.”

Hart reached 128 miles during the first day, soon took the lead, and had a great battle with Gus Guerrero, of California, on day three. “Frank Hart is as graceful as of old and came in for his proportion of the liberal applause.” He soon looked haggard. “Frank Hart is virtually out of the race although he occasionally appears upon the track. As he laid prostrate upon his couch last evening, he presented a sad spectacle. His limbs were swollen to nearly twice their natural size, his eyeballs were sunken deeply within their sockets, and the pedal extremities, which had traveled so many miles, were ornamented by large blood blisters. The colored champion will probably never again be seen in a race of this description, as he realizes that the time is at hand when he must acknowledge his younger superiors.”

On day five, he was rolling again, but far behind. In the past, he would always quit in these circumstances, but he pressed on. He finished with 425 miles, in sixth place, enough to have a share of the prizes. But because of poor attendance, he did not win much. At least he proved to America that he was not dead yet, and his running career was continuing.

At the end of January 1894, he competed in a 27-hour race in Buffalo, New York, where he finished third with 121 miles but received very little money for his effort. “The dividend for the contestants was hardly perceptible under the microscope.” It just wasn’t worth it.

A Year Retirement

Hart and other six-day pedestrians went into serious retirement from competition in 1893. There were only a few six-day races held that year, and Hart did not enter any of them. Some pedestrian historians have written that the sport was a passing fad, that the public had lost interest, or that cycling pushed it aside. This was not entirely true. They failed to understand what truly caused the sport to pause for several years.

This multi-year pause was caused by the panic of 1893 which caused a deep economic depression across America. People rushed to withdraw their money from banks and a credit crunch rippled through the economy. Five hundred banks closed and about 15,000 businesses failed. The unemployment rate was severe in states that had hosted six-day races, 25% in Pennsylvania, 35% in New York, and 43% in Michigan.

The wealthy sports promoters could no longer take the risk of putting on a race that was sure to lose money. Hart again announced his running retirement, but later in 1894 ran a short two-mile race against the legend, Daniel O’Leary and won. The six-day sport took a rest and so did Hart. Because of the depression, from 1893-1897, there were only eight six-day races held in America during those years.

Athletic Trainer in Chicago

The early cycling sport was a white-dominant sport, mostly participated in by the middle and upper class. The League of American Wheelmen (L.A.W., founded in 1880 in Rhode Island) implemented policies that made it hard for non-whites to enter the sport. Clubhouses were built to store bikes, but they became increasingly exclusionary to the white upper-class males. By 1885, a more affordable bike model was invented in England, allowing more women and non-whites to enter the sport. Bike prices fell from $100-150 to about $30. But clubs, including L.A.W. clubs, started to implement more formal bans on memberships. Historian Jesse Gant explained, “Critics were deeply concerned that the bicycle would afford greater mobility and political power. The League thus stepped up its exclusionary efforts after 1893. These labors culminated in a ban on African American bicycling following a League meeting in Louisville, Kentucky, in 1894.”

With ultrarunning, Hart had been used to inclusiveness. He could participate in races despite being black. But as he entered the cycling sport in 1895, he saw alarming racist attitudes and he was not shy in speaking out against them. Hart was bold and believed that the same principles seen in ultrarunning/pedestrianism should exist in cycling. He pointed out that in the East, every club had a black trainer, but that was not the case in the West (Midwest).

This quote from Hart revealed his deep feelings about racial barriers and prejudice. “I ride a wheel (bike) and know several other excellent riders of color in the west who have tried to get into the road races but are shut out by that ironclad color exception in the L.A.W. Now if bicycling can be got so that some enterprising manager can put on races and fill them so that every person, regardless of color, can enter them and compete, it will then be truly an American sport. Bicycling as it is now conducted by the L.A.W., is the most narrow and prejudiced of any of the popular sports in the country. All that is needed is a few men with means and who have backbone to make this sport a truly American one. There has always been a color prejudice toward colored men entering any of the sports in this country. I believe that we will yet produce some colored champions in the country, notwithstanding the fact that L.A.W. has forever closed the door on us. The rest of the world is open to us.”

1895 Six-Day Race in Minneapolis, Minnesota

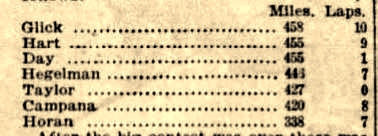

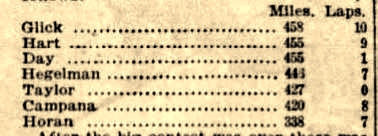

The race was held at Washington Avenue Rink, in Minneapolis, on a track fourteen laps to the mile. It was the first six-day race to be held in the city in four years. “The rink has been thoroughly heated, and a profusion of electric lights and bunting make it attractive.” It could hold 5,000 spectators and they were entertained by the music of the First Regiment Band. Nineteen runners, including a runner from Cape Town, South Africa, Scotty Kennedy, started. Eight of the runners, including Hart, had experience going over 500 miles in past races. During the first 24 hours, Hart reached 121 miles and he covered 204 miles after 48 hours. In the end, he placed second with 455 miles, but ten miles short of sharing in the gate receipts. For all that effort, he made minimal money.

In 1896, Hart continued to live in Chicago, Illinois, and went back to training members of the Aeolus Cycling Club in Chicago with some good success achieved by his riders. While he had no true skill in riding, he was able to teach endurance training and how to succeed in racing for multiple days. He also stayed very busy serving in different roles at race events. He was the chief scorer at a women’s six-day bicycle race, and as the judge of walking, at high school and intercollegiate track and field events. He even served as the announcer at a race meet of the Royal Cycling Club in Chicago. He was finally giving back to endurance sports. Some elite cyclists sought out Hart to train them.

Heel-Toe Six-Day Walking Match in St. Louis

But compared to running, biking, and roller skating, strict heel-toe walking matches were no longer very popular. “The race is too slow and uneventful to suit the populace of today. It is necessary now to satisfy the public taste to travel fast and far, otherwise, the affair ends in the same financial disaster as did the match at the Natatorium. Walking only twelve hours a day did not wear them out so much that they could not recuperate.” Spectators wanted to see race contests that involved suffering and crashes.

Bankers Athletic Club

In 1897, Hart, now in his early 40s, was employed as a trainer for the Bankers’ Athletic Club in Chicago, Illinois, which was established in 1896 for bank clerks, with an initial membership of seven hundred. He trained both runners and cyclists on the south side of Chicago, on the club’s grounds on 35th Street with a track, baseball diamond, and grandstands. (It became known as “Banker’s Field” and was near the future site of Comisky Park, home of the Chicago White Sox.) They also eventually acquired headquarters for the club at 106 Madison Street on the fifth floor. When Hart was hired, the cycling club had five hundred members. During the summer of 1897, Hart oversaw the outdoor cycling meets organized by the club on their new grounds. He was also employed as the groundkeeper for the baseball diamond. Finally, he had a nice steady job that he enjoyed. At the end of the year, he was appointed secretary of the club.

In February 1898, Hart started personal training for a six-day race to be held during March in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. “His work consists of running and walking and he is rapidly rounding into shape. He thinks that he is as good a man as he ever was and expressed confidence in his ability to win.” It was all for not, the race was canceled.

Death of Hart’s Wife

On November 19, 1898, Hart’s wife, Mary, died at the age of 42 of Tuberculosis, in Boston. He had not lived with her for years. Her address was 56 North Anderson Street, still on the property where they had lived since their marriage. Today a parking garage for Massachusetts General Hospital stands there.

The Last Six-Day Race in Madison Square Garden

In 1899, Hart had hopes to compete in a six-day race to be held in Madison Square Garden, the first there in eight years, but also the last in history. Many “old-time cracks” planned to be there. However, a recent local law limited athletes from contesting for more than 12 hours per day. To get around this law, the event was split into two waves, 12 hours each day, so that it could be a continuous event for six days. Hart was assigned to the second group with many of the old-time famous pedestrians to start at noon.

The whole event illustrated the downfall of the six-day races. From the beginning, it looked like it would be a financial fizzle. Before the second wave finished, the event was canceled because the rent was not paid. The crowds were very small. “A. R. Samuels, the manager, looked sadly at the impoverished audience about 10:30 p.m. and had then quietly stepped out to get a breath of fresh air. He did not return. He left behind thirty indignant athletes, some of whom were in bad financial straits, and all of whom had lost sums.” Samuels had rented the Garden for $5,000 but took in only $142 on the first day. It appears that Hart quit the failed race very early or wisely did not start. The last six-day race ever held in Madison Square Garden sadly went down in flames. New York City was through with six-day pedestrianism for the next seven decades.

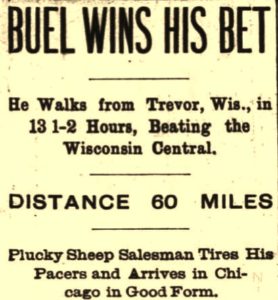

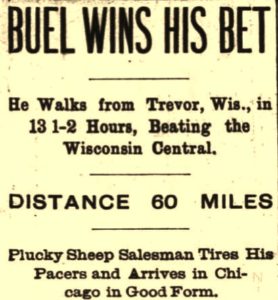

Race Against and Freight Train

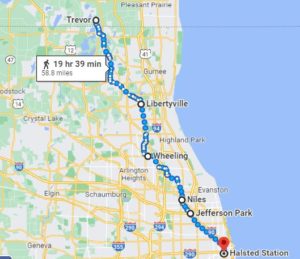

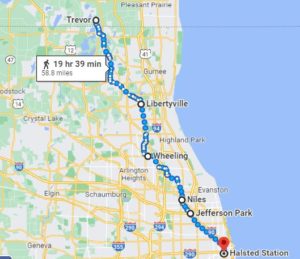

In May 1899, Hart started training an amateur runner, Charles Leroy Buel (1852-1935), age 36, a sheep salesman, for a stunt. Buel was disgusted with the performance of the Wisconsin Central railroad, which would take 18 hours to transport his sheep from Trevor, Wisconsin, to the Chicago stockyards, about 60 miles. On one trip, some of his sheep died because of the long, shaky trip. He took up a $500 bet with a railroad man that he could cover the distance on foot faster than the train.

Buel started on May 20, 1899, at 3:30 a.m., accompanied by Hart as a pacer. “Quite a crowd had gathered at the Trevor depot to witness the departure and cheered as the party disappeared in the darkness.” Buel ran eight miles during the first hour, making it difficult for Hart to stay ahead. Two other pacers rode a tandem bike and spelled Hart at times. As Buel entered Chicago, thousands of people lined the sidewalks and cheered him on to the finish. Buel was successful, reaching the stockyards with about five hours to spare, in 13:36. “He stated that he had no intention of being a professional pedestrian, as the stock business was good enough for him.”

Hart’s Final Six-day Races

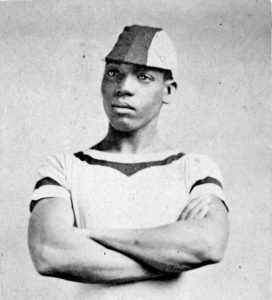

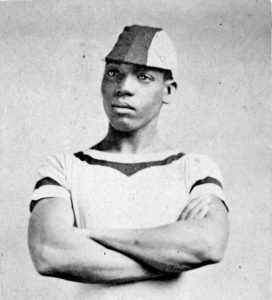

![]()

![]()

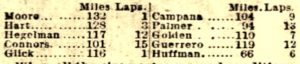

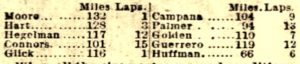

On February 11, 1900, Hart, age 43, surprised many when he held a commanding lead in a six-day race held in St. Louis, Missouri. He covered 124 miles during the first 24 hours, and 198 miles in 48 hours, competing with 27 starters. Blisters then plagued him, and he slowed. He finished far down in the standings, with 390 miles.

Hart’s Family

With Hart living in Chicago and staying away from Boston for multiple years, where were his children now that his wife was dead? In June 1900, his son Frank S. Hart was 23, still living at the North Anderson St home in Boston, with his youngest sister Adelaide Hart, age 17, a dressmaker. Also in the home were their aunt and some cousins, relatives of their late mother. Frank Jr. was working as a museum attendant. Two months later he married a white Swedish woman, Ellen Anderson, and he was working as an actor.

On July 30, 1900, Hart married again, to a widow, Cora (Posey) Thomas (1858-1924), age 42, from Salt Lake City, Utah. He evidently met her while judging a cycling meet at the Salt Palace saucer track on 9th South between State and Main Street. Cycling promoters had constructed a unique track with 43-degree banked curves on an oval track, eight laps to a mile. Cyclists from around the country flocked to race on it and try to break world records on the extremely fast track. Hart took some of his trainees there to compete in early July.

Hart and Cora’s courtship was fast, just a few weeks. They were married in Grand Rapids, Michigan. In the marriage record, Hart was listed as an athlete, with the West Indies as his birthplace. His parents were listed as Joseph and Elizabeth (Mallory) Hart. Cora was a hairdresser who had been born in Indiana and it was her second marriage. Her first marriage was in 1884 to Samuel Thomas in Indiana. He died in 1897.

Six Day Races Come Back in Pennsylvania

A year later, he competed again, this time in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania at the Industrial Hall on Mar 11, 1901. Six-day races had experienced a good resurgence in Pennsylvania. Twenty-four runners started on the 17 laps to a mile track. Still, in great condition, Hart stayed with the leaders and approached 200 miles on day two, but suffering from sleep deprivation. “Hart several times staggered against the railing, opened his eyes in surprise, and then plodded sleepily on.”

The leader was John Glick (1869-1929), a weaver from Germantown, Pennsylvania. He would stagger many times into the wrong hut and started to go cranky. “Music may have charms for the savage beast, but John Glick is not built that way. The sound of the hand organ playing increases his flightiness, and last night he threatened to throw the organ out the window.”

Hart struggled on the third day, logging few miles, but was renewed the next day and went around the track “at a lively clip,” just hoping to finish well. He was 138 miles behind the leader but still determined and finished in 8th place with 314 miles. He won $90.

Just before the end of the race, Hart kindly wheeled Peter Hegelman (1864-1944), a German-American from New York City, around the track on a hand chair to bring attention to him. The doctors would not let Hegelman continue because he was “a little bit gone in his mind.” A hat was passed around to collect something for him. Hart came out of this race with a badly sprained ankle with rheumatism.

Training James Dean

In November 1901, Hart took on the responsibility to train/handle James Dean, a stenographer from Boston, Massachusetts. He was another talented black pedestrian who had been beating Hart in recent races. Hart served as Dean’s trainer at a six-day race in Pittsburgh’s Old City Hall.

During the race, Dean suddenly accused Hart and his team of attempting to poison him and then would not accept food from them unless it was first tasted by someone to prove that it wasn’t poisoned. After he reached 412 miles on the last day of his six-day race, he was in a “daffy” condition, and he was taken to the hospital. He then escaped his attendants while in the bathroom, went through an open window, and down a fire escape.

“A search was at once instituted and kept up for several hours without finding any trace of the missing racer.” He was later found wandering the streets and was taken to the police station. “His clothing was covered with blood, the result of a hemorrhage from his nose. He was ragged and covered with dirt. He was wholly irrational and babbled meaninglessly.”

Hart soon arrived and took the “demented man” to St. Francis Hospital. “It is said that Dean was completely broken down from his exertions in the race. He will probably recover after rest and treatment.” After another day in the hospital, Dean recovered well and two months later was again competing in a six-day race.

Hart’s Last Six-day Race

Later in the week, he took part in short exhibition races on the track to raise funds for runners to return home. Hart controlled how the purses would be dealt out. Peter Golden (1943-1933), lodged a protest. “Hot words passed between Golden and Hart, and after the men had prepared themselves for the street, they came together in the armory. They were ordered from the premises and were about to continue the mill on the outside when friends of both men interfered.” All this was over only a few dollars. With that, Hart disappeared from competing in the sport at the age of 46. He continued to train athletes.

Hart Seriously Ill

Four years later, in 1906, it was reported that Hart, age 50, was penniless, suffering from tuberculosis, and living in Colorado for his health. Sad news spread across the country that he was dying. He was dependent on friends for all his needs.

Apparently, Hart was not that low. In May 1906, he was in St. Louis, Missouri, and crewed a runner in “The Great Marathon Race of Missouri” won by the great ultrarunner of the next generation, Sidney Hatch (1883-1966) in 2:46:14, just a minute ahead of Alexander Thibeau. They were both from Chicago. Hart was crewing for Lewis Marks of Chicago, who finished in third place. The runners’ crews followed them in automobiles. It was reported, “When Frank Hart, the old negro go-as-you please pedestrian saw Thibeau and Hatch, he jumped out of his auto and, running beside Marks, besought him to run faster. Marks was sore and surly, refused to answer or to run.”

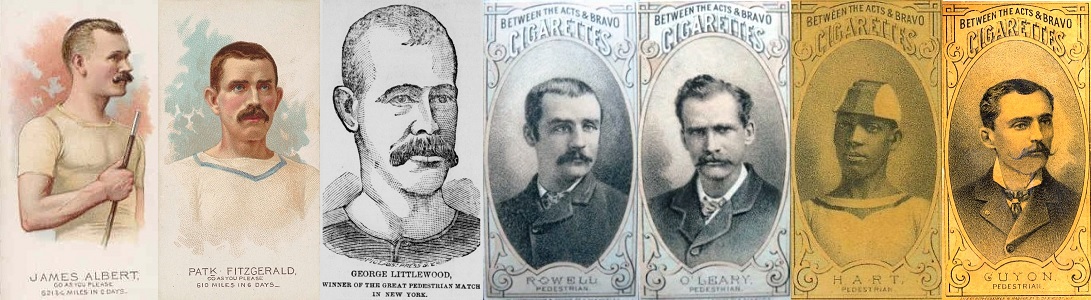

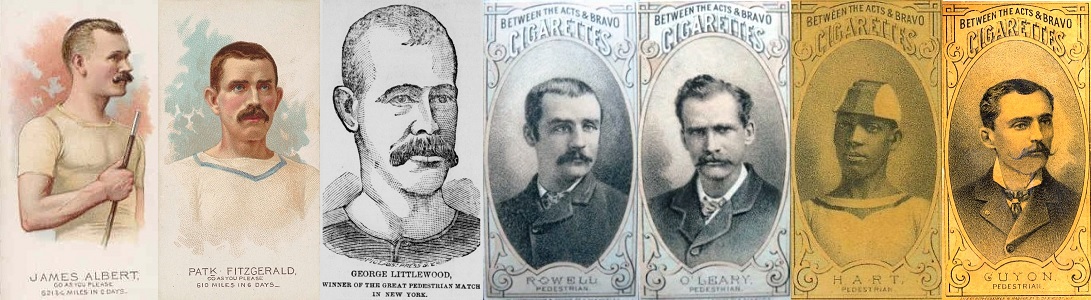

In 1906, most of Hart’s fellow old-time pedestrians had also retired from the sport, many who also lost their fortunes due to the depression and mismanagement of finances. Napoleon “Old Sport” Campana (1836-1906) was selling chewing gum on the streets of Chicago and was seriously ill. Gus Guerrero was a gate-tender on the Broadway subway in New York City. Henry O. Messier (1862-1945), the sport’s historian, was a book salesman. James Albert (1856-1912), the American six-day record holder (still holds the record with 621 miles), was operating a cattle ranch in Texas. Patrick Fitzgerald (1846-1900), former world record holder and alderman in New York had recently died. The former six-day world record holder, Robert Vint (1846-1917), the shoemaker, lived in California. George D. Noremac (1852-1922) was operating a hotel in Philadelphia. Peter Golden (1943-1933), and Peter Hegelman (1864-1944), were clerks in New York City. John Glick (1869-1929) was working in the cotton mills in Philadelphia. Edward C. Moore (1860-1927) was in Europe working for the Standard Oil company. Richard Lacouse (1848-1923) was a bricklayer in Montana. George W. Guyon (1853-1933) was a “tinker” in Oklahoma City.

Hart’s early trainer, John D. Oliver “Happy Jack Smith” (1860-1914) was still training athletes in Massachusetts. Hart’s former partner, Charles A. Harriman (1853-1919) was a farmer and pastor in Rockport, Maine. Hart’s nemesis, John “Lepper” Hughes (1850-1921) of New York City, was operating a saloon. Former six-day world record holder from England, Charles Rowell (1852-1902) had recently died. Another former world record holder, Henry “Blower” Brown (1843-1900) of England had also died. The six-day world record holder, George Littlewood (1859-1912) was in business in England. Daniel O’Leary (1846-1933), Hart’s original mentor, was still walking, and the next year at the age of 61 would conquer the Barclay Match by walking 1,000 miles, one mile each hour, for 1,000 consecutive hours in Cincinnati, Ohio.

Hart’s Death

On September 17, 1908, Frank Hart died at the age of 52 in his home in Chicago, Illinois due to an attack of pneumonia. “The funeral will be held under the auspices of the lodge of the colored Knights of Pythias, of which he was a member.” He was buried under his given name, “Frank E. Hichborn” on September 22, 1908, in Mt. Glenwood Cemetery in Glenwood, Illinois, likely in an unmarked pauper grave. His occupation was listed as “Athletic trainer.” Ironically, on his death record, his race was listed as “white.” His death, at first, was not widely publicized, only mentioned in Racine, Wisconsin.

Nearly five months later, a detailed article was finally published about his death entitled, “Once Famous, But Died Obscure.” “Frank Hart, one of the wonders of the cinder path, died a short time ago in Chicago, with no mention in any paper except that a pauper had passed away and had been buried by charity.” It was doubted if his wife and two children who lived in Philadelphia had been notified.

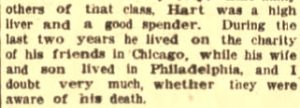

Fellow pedestrian, and trainer of cyclists, Henry O. Messier, of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, wrote, “He died penniless in Chicago, and from what I hear, his friends buried him. Hart met and defeated the best six-day go-as-you-please men of the world and won five championship belts. Hart was a high liver and a good spender. During the last two years, he lived on the charity of his friends in Chicago.” The Cleveland Gazette printed this death announcement with a misprint, stating that Hart had lived on the charity of his friends for 20 years instead of 2 years, which was an error because in those last 20 years Hart received some massive winnings in 50 races and was also a successful trainer. This error has been copied in many modern pedestrian histories.

Frank Hart was truly one of the greatest American ultrarunners of the 19th century. He made it possible for many black runners of his era to compete as well. He was a hero and an idol. Running was certainly his entire life, but he had his serious flaws. His drive for fame and fortune came at the expense of his family and many friends who tried to help him, but were pushed away. He was determined to excel and sought the recognition he deserved, but often was not given enough respect because he was black.

While most Americans have never heard of Frank Hart before, he remains one of the first nationally famous black athletes in America, the Jackie Robison of 19th-century ultrarunning/pedestrianism. As Jim Crow laws and more bigotry took hold in the 20th century, all sports experienced a setback in inclusiveness. There were some exceptions. In 1928, Charles C. Pyle (1882-1939) allowed five black ultrarunners to compete in his race across America, nicknamed, “The Bunion Derby.” It wasn’t until the 1950s that Ted Corbitt (1919-2007) of New York City, again crossed that racial barrier and became the “Father of American Long-Distance Running” in the modern era. But Frank Hart was truly the first black famous ultrarunner in history.

Frank Hart Series

- Part 1: First Black Ultrarunning Star

- Part 2: World Record Holder

- Part 3: Facing Racial Hatred

- Part 4: Former Champion

- Part 5: Declining Running Career

- Part 6: Final Years

Sources:

- St. Louis Globe-Democrat (Missouri), Dec 13, 20, 1892, Jan 4, 1897, Feb 12-18, 1900

- St. Louis Post-Dispatch (Missouri), Dec 13, 23, 1892, May 6, 1906

- Pittsburgh Post-Gazette (Pennsylvania), Dec 17, 1892

- Vancouver Daily World (British Columbia, Canada), Dec 22, 1892

- Manitoba Semi-Weekly Free Press (Winnipeg, Canada), Dec 26, 1892

- Chicago Tribune (Illinois), Jan 23, 1897, Nov 18, 1898

- The Inter Ocean (Chicago, Illinois), Aug 4, 1894, Feb 1, 1898

- Buffalo Courier (New York), Jan 28, 1894

- Jesse Gant, 19th Century, 20th Century Whites on Bikes

- Molly Huber, Bicycling Craze, 1890s

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Nov 28, 1892, Aug 7, 1895

- The Journal Times (Racine, Wisconsin), Nov 15, 27, 1895

- The Saint Paul Globe (Minnesota), Nov 24, 1895

- Star Tribune (Minneapolis, Minnesota), Dec 1, 1895

- The Chicago Chronicle (Illinois), Apr 26, 1896

- The Nashville American (Tennessee), Jan 23, 1899

- The Brooklyn Citizen (New York), Jun 11, 1899

- Philadelphia Times (Pennsylvania), Mar 9, 13, 16, Apr 16, 1901, Mar 16-17, 1902

- Philadelphia Inquirer (Pennsylvania), Mar 14-18, 1901

- The Buffalo Times (New York), Apr 16, 1901

- The Wilkes-Barre Record (Pennsylvania), Oct 10, 1901

- The Pittsburgh Press (Pennsylvania), Nov 17, 1901

- The New York Times (New York), Feb 8, 1902

- Detroit Free Press (Michigan), Apr 6, 1902

- Post-Crescent (Appleton, Wisconsin), Feb 28, 1906

- The Journal Times (Racine, Wisconsin), Sep 23, 1908

- The Kansas City Star (Missouri), Feb 7, 1909

- The Lincon Star (Kansas), Feb 9, 1909