Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 25:13 — 33.2MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Andy Milroy

You can read, listen, or watch

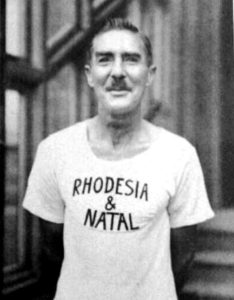

The forgotten man of Ultrarunning is arguably Hardy Ballington (1912-1974), lauded in 1939 in Natal, South Africa, as “the second Newton” and a “human machine”. Dominant immediately before and after the Second World War, he was awarded the prestigious Helms Trophy for his remarkable performances In England in 1937.

The forgotten man of Ultrarunning is arguably Hardy Ballington (1912-1974), lauded in 1939 in Natal, South Africa, as “the second Newton” and a “human machine”. Dominant immediately before and after the Second World War, he was awarded the prestigious Helms Trophy for his remarkable performances In England in 1937.

The authoritative Lore of Running, (2003) written by Professor Tim Noakes, advocated a training programme drawn up by Hardy Ballington and his archrival and friend Bill Cochrane. The program provided daily, weekly, and monthly training goals in terms of total distance covered; it was focused on gradual progression in training but did not specify the intensity of that training. The goal was to condition the body to run the long distances required for an ultramarathon. Ballington’s training strategy was still seen as relevant 70 years later!

| The Ultrarunning History Podcast is included in the People Choice podcast awards in the history category. Please help me by voting for the Ultrarunning History Podcast. During July 2021, go to https://podcastawards.com to register and nominate “Ultrarunning History” in the “History” category. Thanks! |

Early Family Life

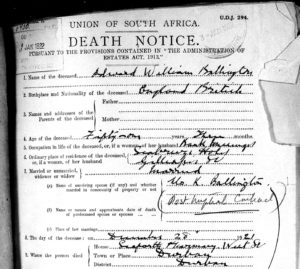

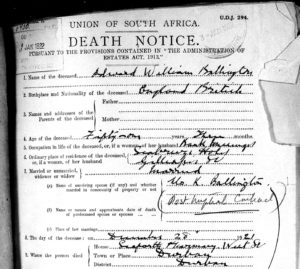

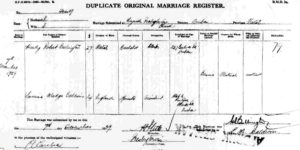

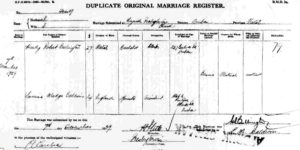

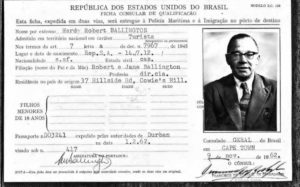

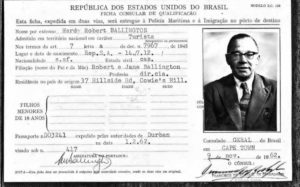

Hardy Robert Ballington was born on the 14 July 1912, in Durban, one of the major ports in South Africa. His father was Edward William Ballington and his mother Kate Elizabeth Sims, both born in England. He was one of five brothers and two sisters, the third eldest child, one of twins.

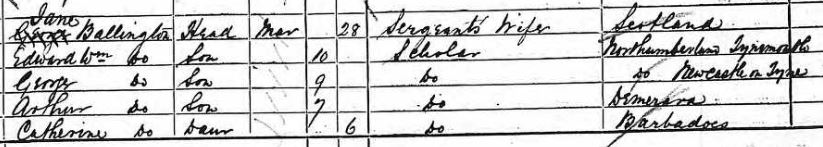

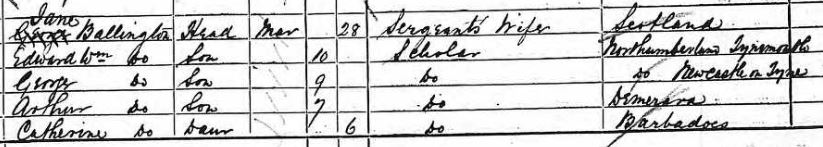

His father, Edward, came from a peripatetic military family, which was not uncommon during the height of the British Empire. Born in Tynemouth in the north of England in 1870, he enlisted in the North Staffordshire regiment of the army at age fourteen but must have been discharged for some reason. By 1892, at the age of 21, he was working for the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway as a shunter/switcher. Life was rough. That year he was convicted for stealing twelve table knives and two pair of carver’s knives and sentenced to one month at a prison in Wakefield. A number of years later, Edward likely re-enlisted in the Army at the outbreak of the Boer War. In 1905 he was awarded the South African medal and clasp.

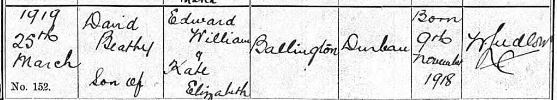

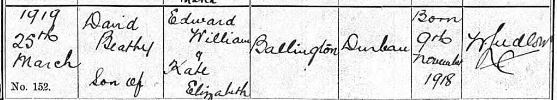

In South Africa he met and married an English immigrant, Kate Elizabeth Sims and in 1910 they had their first son Edward William, named after his father. Another son Basil followed in 1911, twins Hardy and Ernest Stanley followed in 1912, Jean in 1914, Doris in 1916, David in 1918 followed by John in 1920. In 1915 the whole family to that date, all four boys, travelled by ship to England, presumably to see grandparents and other relations. This was the first of Hardy’s trips to England.

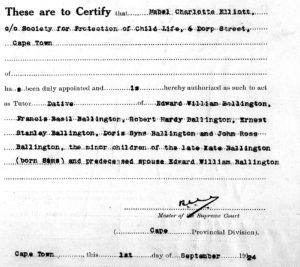

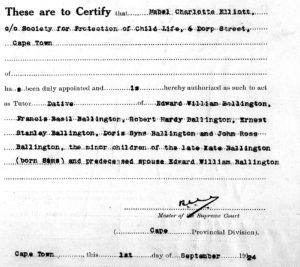

Tragedy struck the young family. In 1921 his father died prematurely in his early fifties, leaving his wife to take care of six children alone. But worse was to follow. In 1924, the 40-year-old Kate Elizabeth gave birth to her eleventh child, but complications and a heart attack caused her death. The baby died. The six living Ballington children were orphaned. The eldest, Edward, was fourteen years old. Hardy was only eleven.

With seemingly no relatives in South Africa, caring for eight orphaned children, with the youngest only four years old, was problematic. The six minor children were initially put in the care of the Society for Protection of Child Life in Cape Town. There was a Children’s Aid Society in Durban which could provide some financial and emotional institutional support. In 1923 an Adoption Act had been passed and the Greyville Crèche was a primary school for the care of white children in Durban. It is unlikely that the Ballington children were kept together if adoption was an option. (Later in life Hardy listed Robert and Jane Ballington as his parents, so he may have been raised by relatives.)

Early Running

By age 18, in 1930, at a diminutive 5’ 2.75” or 5’4” (sources vary) Hardy had also become fat and unhealthy, and after a period in hospital, he decided to take up running to get fit. He began his new regime almost furtively, after night classes and early on a Sunday mornings before sunrise – so no one would see him. He trained on roads, seldom used, to avoid recognition, and had no intention of competitive running. Distance running gave him a sense of control, of order and structure. He was drawn to the effectiveness of generating and implementing schedules and routines, the positive feedback giving him security.

Ballington’s First Comrades

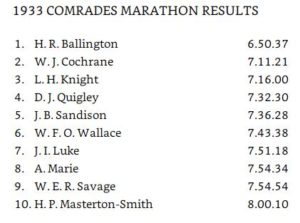

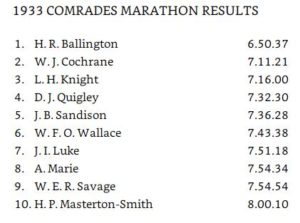

First Two Wins at Comrades

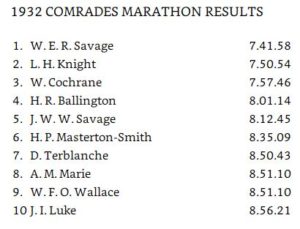

By then Hardy Ballington was being coached by legendary Arthur Newton. (See episode 59). He followed Newton’s heavy mileage advice, and in four days over Easter he had covered 104 miles (33 miles, 33 miles, 34 miles and 40 miles.) Back in 1931, (half a year) he trained 1,091 miles, in 1932, 2,132 miles. By the time he retired in 1938, he had trained 22,500 miles.

Like Newton, he ran flat-footed, placing his feet very deliberately. As he trained, Ballington took a drink every seven miles, usually lemonade fortified with sugar and salt, again following Newton’s advice. On the 18 November, 1933 he won the Durban Athletic Club Marathon in 3:08:04.

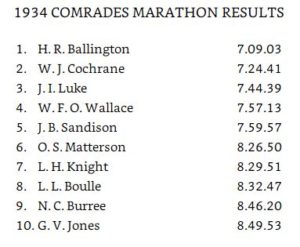

Cochrane was in the lead and Ballington set off in relentless pursuit. He passed him and went on to win in 7:09:03. Cochrane came in second again with 7:24:41. Hardy Ballington became the first man since Newton to win the Comrades twice.

In an article he wrote in 1968, Ballington recounted a story which shows both his lack of ego and his strong friendship with Bill Cochrane and Vernon Jones. It took place after the 1934 Comrades and involved Ballington’s youthful looks. “The following Sunday I took a drive with my friends, Vernon Jones and Bill Cochrane to a Tea Garden for morning tea and to relax. Nearby, two little girls aged about seven and nine years were playing on a swing. After a while one of the little girls came up to me and said, ‘Sonny, won’t you come and swing with us?’ Vernon Jones has never let me forget that incident.”

The fact Ballington should include such a story in a piece he wrote, which reflects on his diminutive stature and very youthful looks, (he was twenty-two but looked much younger, as if his early teens) when he had just recounted winning the Comrades for the second times, shows both his humility and his down to earth nature. His close friendship with his greatest rival is indicative – in training they would bluff each other with their mileages. Yet the trip out for tea was typical, the two would share a four-penny orangeade at a tearoom on the Comrades course if they met up.

Again, in November 1934, Ballington won the local Durban Marathon, running 2:45:00. In April 1935 in the South African marathon championships in Pretoria, Ballington had finished second to Jackie Gibson, a marathon specialist, in 3:04:25.2. Gibson ran 2:52:40.4 to win.

1935 Comrades

In the 1935 Comrades, Hardy Ballington was faced by another top South African marathon runner, Johannes Coleman (1910-1997). Ballington was aiming for a hat-trick of wins, but as before, was also racing his great friend and rival Bill Cochrane. Cochrane reputedly was keeping track of Ballington’s training. He would then go out and try and surpass it.

By the halfway point of Comrades, Cochrane was at 3:04:15, with Ballington exactly two minutes back. Coleman came through into second, and Ballington slipped to third. However, Ballington came forward again, but he was unable to make up all the ground. He was on the track at the same time just 1:45 behind. Cochrane finished first in 6:30:05 to Ballington’s 6:31:56. Johannes Coleman suffered a rare defeat by two South Africans, third in 6:55:20. Bill Cochrane then announced his retirement, having succeeded in his great ambition, to win the Comrades. He was just 24 years old.

Olympic Marathon Trials

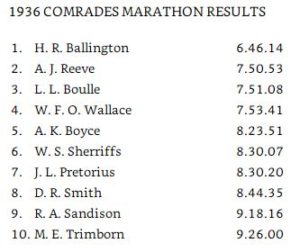

Early in 1936, Hardy ran in the Olympic Marathon Trials in the South African Marathon championships at Port Elizabeth against some of the fastest marathon runners in the world. He finished fourth behind Johannes Coleman, Jackie Gibson and Wally Hayward. Coleman ran a new Africa record of 2:31:57.4, Gibson 2:32:09 and Hayward 2:43.

1936 Comrades

As compensation for being close to making the Olympic team and for breaking the Up course record, it was suggested, reputedly by Vernon Jones, that he also be sent to Europe to attempt Newton’s London to Brighton and Bath Road 100-mile course records.

To England in 1937

In the programme of the 1968 Durban 100-mile track race, Hardy Ballington wrote his recollections of his attempt on the 100-miler record. (See also episode 60).

“Since 1933, I had shown steady improvement in my running, and now in 1937 the Durban Athletic Club members considered I had attained world class and decided to send me to England to run in the London to Brighton race, and also the 100 miles from Bath to London.

“What a difference there is in travelling today as compared to how I did in 1937. I had to go by sea and spend over three weeks on board from Durban to England. My big trouble was to keep fit. During the four days stay in Cape Town I did over 200 miles training around Table Mountain. After leaving Cape Town I had to get up every morning at 2 a.m. and train around the deck of the ship. Twelve times around the deck equaled one mile, and I averaged 300 laps each morning.

“On arrival in England. I was met by the great Arthur Newton. It was our first meeting, although we had corresponded for several years. Arthur Newton introduced me to Joe Binks, the Sports Editor of The News of the World. Joe Binks wrote in his paper that South Africa had sent a schoolboy over to do a man’s job and was not impressed. However, this made me all the more determined and I moved into the country to concentrate on my training.”

London to Brighton

The News of the World report described the scene at the beginning of the London to Brighton race. “It was a fine, bright morning when the eight runners lined up under Big Ben, (the clock of the Houses of Parliament.) The enthusiastic early spectators gave them a hearty cheer as they went off.”

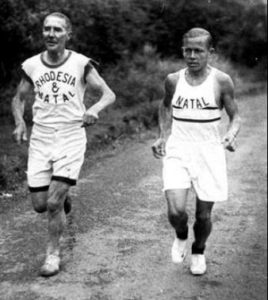

Hardy Ballington and J H Chapman, a 2:57 marathon runner who had finished 4th in the tough Polytechnic Marathon that year, led the way, reaching Streatham (five miles) in 32:33. At the Greyhound public house at Croydon (10 miles) the leaders were at 63:45, slower than Arthur Newton’s split time when he set the course record. H Barraclough (Yorkshire) was third in 66:49.

Then a strong, south-west wind and heavy rain began. Ballington continued with a decidedly powerful action. Twenty miles was covered in 2:09:15 (Newton had run it in 2:04:15). At Harley, Ballington in the lead was running like a machine, reaching halfway in 2:36:40, within four minutes of the record. He said he would not mind the rain increasing, if only the wind would ease. Despite the conditions, by Crawley he gained on the record (3:10:54 for 31 miles 1408 yards).

Conditions worsened, Ballington felt the record was beyond him, but was reassured by Newton who was handling him. Ballington later wrote “In the early stages I experienced quite a lot of muscle trouble, caused by the cold weather, and I must say if it had not been for Arthur Newton, I doubt I would have made the grade.”

By the time Ballington had reached Handcross he was timed at 3:41:02 – 55 seconds inside record pace. He was still facing heavy rain, but by 38 miles (Bolney), he was two minutes 40 seconds ahead (4:09:30). The 40-mile point was reached in 4:23:17, but Ballington now faced the climb to the top of Dale Hill to Pyecombe. He did so strongly that he was 7 minutes, 4 seconds ahead of the record by then.

The newspaper described Ballington at the finish. “His eyes were feeling rather sore from the buffeting of the wind.” But remember his first Comrades win had been in cold, wet conditions which suited the small, compact Ballington.

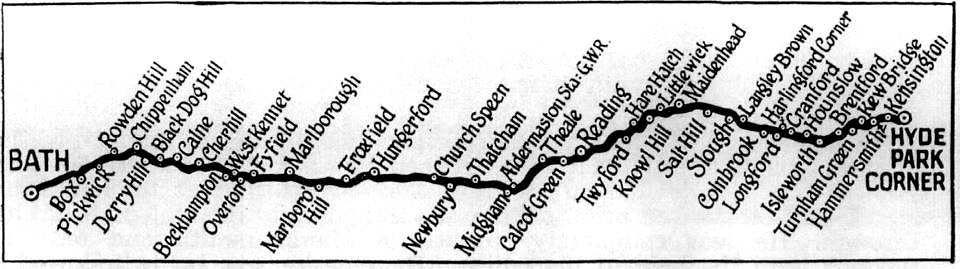

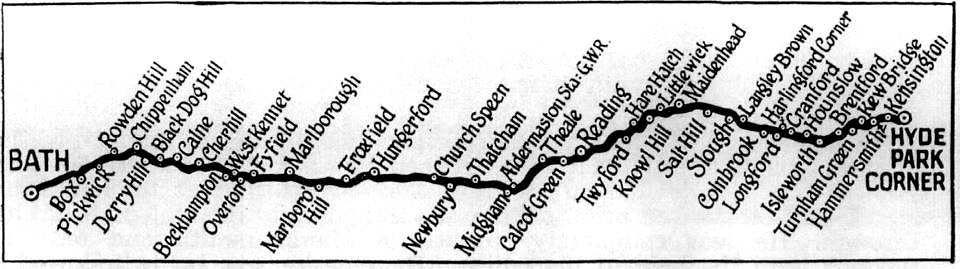

100-mile Record Attempt on Bath Road

After winning the international London to Brighton, Hardy Ballington later wrote: “I moved to the West Country to train for the 100 miles from Bath to London. During the month of June, the weather was perfect, and I covered over 1,400 miles in training (46 miles/75 km a day – Ed.). I stayed in Newbury for a while and then decided I would like to move nearer to Bath, so arranged to stay with people near Marlborough. You can imagine my surprise when I turned up at the residence, to be told that there was no bath in the house and if I wanted a bath, I could use a tub in the living room once a week. You bet I decided to stay in Newbury.

“The 100-mile was run on a very hot day, the 3rd of July,1937. It was a very interesting road, right across England, and ending up in the heart of London”

Vernon Jones, in Lore of Running (1987) said Ballington was clearly over trained when he started the run with a severe headache. He complained that he felt “tired and fagged out.” The heat was so intense in London that day the Wimbledon tennis finals had to be delayed by two hours. Handling Ballington were Arthur Newton and M B McNamara, who had run 14:09:45 for 100 miles in Canada when Newton had set his 24-hour world best.

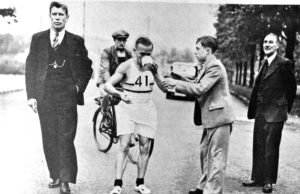

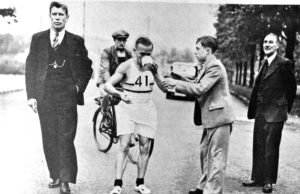

After a good breakfast of scrambled eggs and toast, Ballington set off at 3:30 a.m. The starting point was at the Bear Inn, in the small village of Box in Wiltshire, on the A4 route to Hyde Park Corner in London, the starting point for all roads to the West of England. His aim was eight miles an hour, 180 steps per minute. Just as at London to Brighton, Ballington set off at a more even pace than Newton had in 1928. He reached ten miles in 1:13, six minutes slower than Newton.

Ballington was running at eight and a quarter miles an hour at the start, reaching 20 miles in 2:25:30. He was also handled by a young man from Durban, G C M Fletcher. Fletcher would jump out of one of the accompanying cars, discover what drinks Ballington needed, then return to the car. The car would then drive on 100 yards ahead, so the drink could be prepared. Twenty-five miles was reached in 3:01:30 and 30 in 3:38:45. Forty miles came in 4:52.

Shortly before 50 miles Ballington was given his first water jug shower to mitigate against the increasing heat. The “refreshment team” was reliant on obtaining fresh supplies on the way. However, one tea shop enroute was not helpful. The thermos flask of hot tea had run dry. Requests to refill it were firmly rejected. Tea could only be consumed from cups whilst seated in the tea shop. Fortunately, Ballington was able to have tea when a more co-operative catering establishment was found. The water jug showers were given after each drink, and in between as well. This reflects just how hot it was and explains exactly why Ballington got blisters as the skin on his feet was softened by the water. The combination of the cold water showers and a light breeze kept Ballington comfortable.

At 55 miles a roadside water pump was found, the water jugs topped up. McNamara‘s vigorous pumping enabled Ballington to have a good soaking. He then switched to his normal drink of lemonade with additional salt and sugar. After 60 miles, hot tea and lemonade were constantly needed every couple of miles. This was followed by his first solid food – jam sandwiches supplemented by still more fortified lemonade. He went through 65 miles (just a couple of miles beyond 100 km) in 8:17:30.

A cyclist joined them and was able to guide the tiring Ballington into and through London to Hyde Park Corner where he finished in a new course record of 13:21:19. He wrote afterwards “I received a tremendous reception on arrival in Hyde Park and broke the world record by over an hour.” After the race, he stayed with Arthur Newton in Ruislip until he was due to return to South Africa.

Back in South Africa

Ballington returned home to a civic reception in Durban to celebrate his feats in England. He was to be employed by Durban City Council in the Treasury Department. In November 1937, Ballington finished second to Johannes Coleman in a marathon at Pietermaritzburg, running his fastest time 2:37:29. Coleman ran 2:32:08.

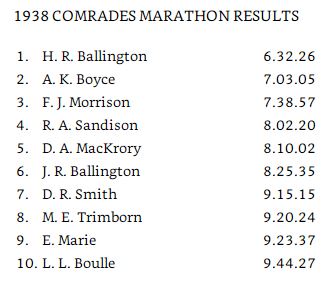

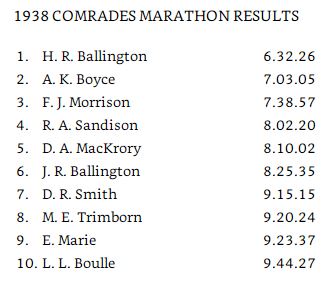

1938 Comrades Win

Hardy was not the only Ballington in the race, his younger brother John was also running. He was coached by his elder brother. Only twenty runners entered the race. Allen Boyce, who had finished second in the 1937 race, took the lead out. But Hardy Ballington soon found the pace too slow. He had his own schedule to keep. Often, he ran for a time, rather than against an opponent. Vernon Jones described him as a perfectionist, whose standards were the very highest. He refused to cut corners, running the whole race on the left-hand side of the road, conscious of traffic.

Early Running Retirement

In 1938, Ballington was 25 years old. Athletics was generally thought of as being part of childhood. By continuing on to run at such an “older” age, Ballington was perhaps threatening his professional career as a clerk at Durban City Council. He had invested a lot of time in night school to gain that position. Bill Cochrane had retired at 24. Ballington is credited with saying “I’ve had enough. I have to get on with my work now, and I can’t manage work and marathon running.”

World War II Years

Hardy and Lorraine had two children, Rosemary and Ross, Ross being a family name, the middle name of his youngest brother John.

The War years are unclear as far as Hardy Ballington is concerned. In South Africa thousands of men of military age went to camps and bivouacs prior to being called up. The decision to enter the War in support of Britain was seen as very divisive, and conscription was not considered. It seems likely that Ballington did not enter the armed forces either for medical reasons or because of his important role in local government. A strong possibility is that he volunteered for army service but was turned down for having flat feet.

In World War II the military turned down thousands of recruits because they had flat feet. Nowadays research is showing so-called flat feet are perfectly functional. Recent studies have shown that those with flat feet have fewer injuries than those with normal or high arches. Years of heavy mileage in both training and races would probably have ensured Hardy Ballington’s feet were flat and functional, shaped by thousands of miles of flat-footed running!

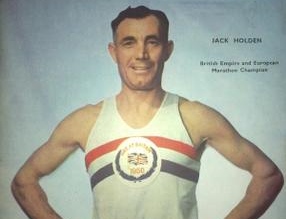

Hardy Ballington obviously remembered his time in England. It is assumed that he met the Tipton Runner Jack Holden (1907-2004) while there. In the years after the War, when food in Britain was limited and rationing was introduced, Ballington sent the Tipton runner food parcels. Maybe these gifts enabled Holden to set a 30-mile track record in 1946, and in 1950 win the European and British Empire Games Marathons.

1946 Comrades

Leading up to the 1946 Comrades, there were only twenty-two starters. Many men had not been demobbed from the South African forces. Hardy Ballington had decided to enter the race and had covered 2,000 miles in training over the previous five months. Unfortunately, a week before the race, he was forced off the road by a car and injured his ankle badly. Bill Cochrane who had been captured in the North African Campaign, had decided in prisoner of war camp to run again. Cochrane won in 7:02:40 after an eleven-year break from the race. Behind him in second was Dymock Parr in 8:00:27.

1947 Comrades

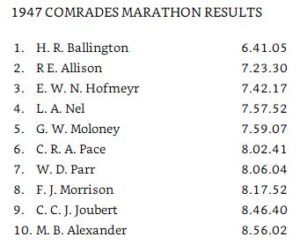

The following year, 1947, Hardy Ballington, age 34, was intent on emulating the feats of his great mentor Arthur Newton and winning a fifth Comrades. Just 47 runners set off. Ballington took the lead after ninety minutes wearing his usual no. 41 number. He reached halfway in 3:04:07 and was ahead of his 1935 time. A course record was possible. But severe stomach trouble caused a bad patch and the record slipped out of reach. He won and finished in 6:41:05. A youngster Reg Allison finished second in 7:23:30. Ballington had won his fifth Comrades, to equal Newton’s feat. He thereupon announced his retirement from the Comrades.

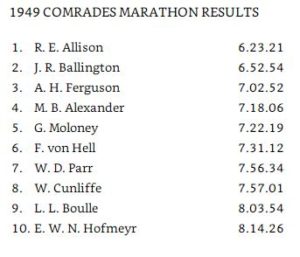

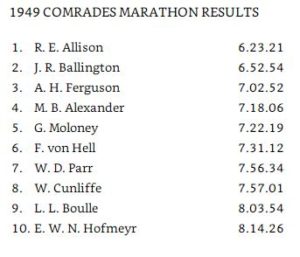

1949 Comrades

In 1949, his younger brother John wanted to retire from the Comrades at 34 miles and again at 45 miles. Hardy responded fiercely “No Ballington has retired yet. If you do, you change your name to something else. Finish and you are still a Ballington” This shows clearly the toughness and determination of Hardy Ballington. It may also reveal the tight kinship that may have bound the orphaned youngsters in the 1920s. It’s effect on his younger brother was dramatic, he finished second to Reg Allison in 6:52:54.

Final Years

In 1948 Hardy Ballington finished fourth in the South African marathon championships in 2:44:20 in Port Elizabeth. This may well have been his last race. As a handler, he maintained his connection with the Comrades, most notably with his brother John. In 1962, a contingent of British runners came to South Africa to contest the Comrades, representing the RRC. The British runners were allocated experienced former runners as their handlers. Ron Linstead was handled by Hardy Ballington and finished fifth. The other runners were handled by good friends of Ballington, John Smith (winner) by Bill Cochrane and Tom Buckingham (fourth) by Vernon Jones. W Don Turner (third) was handled by Allen Boyce.

Ballington also continued his long-distance friendship with Arthur Newton, who he probably saw as a father figure. This continued until Newton’s death in 1959. After the War, Ballington’s work as a travel agent took him to London many times and he never failed to call on the “Old Man” to pay his respects.

Durban had a regular weekly service provided by the Union Castle Shipping Line. Each ship carried 450 tourist passengers. With South Africa’s tourist attractions, Ballington had left the Treasury Department and set up his own travel agency to take full advantage of Durban’s tourist potential. Running such a business appealed to Ballington who worked out schedules and timetables for the Union Castle ships and the trains for prospective tourists and travellers. It was said that he traveled around the world six times during his years as a travel agent. He was a keen amateur film maker, and showed colour films of the Victoria Falls, Drakensberg Mountains and the Kruger National Park, with close ups of lions, giraffes, zebras and elephants in the wild.

In 1968 when Jackie Mekler also won his fifth Comrades, Ballington kindly sent him a telegram that read, “Congratulations Jackie. Your win was fantastic and well deserved.”

Hardy Ballington died in his sleep in April 1974 at age 61. Such sudden unexpected deaths at night were usually due to a heart problem. Both his parents had died unexpectedly, his father at 53, his mother at 40 from a definite heart attack.

His earlier successes as a distance runner would not have protected him from a family history of heart disease. Remember Jim Fixx… An occasional sudden raised pulse rate during his running career could also explain his occasional bad patches.

The collected materials on his running career that were stored in a garage in Westville, Durban were unfortunately lost. His friend Vernon Jones became the only source of information on his running. Ballington followed closely Newton’s ideas of heavy training mileage at slow speed. He was not a fast runner by modern standards with a marathon best time of 2:37:00. But at longer distances he was remarkable. He did no specific speed-training. He competed infrequently and ran long training runs of 40 to 50 miles on the weekend.

Wally Hayward was four years older than Hardy Ballington, born in 1908. After winning the Comrades in 1930 at the age of 21, Hayward had become a track runner, winning national titles, before moving up to the marathon after the War. His transformation to running the longer distances had been painful as he changed to running with a flatter foot instead on his toes.

Hardy Ballington’s last Comrades was in 1947, he was only 34 years old. Wally Hayward returned to the race in 1950 at the age of 41. Hayward was to go on to win five Comrades Marathons and to set world track records. But the world was never to see the two great runners compete head-to-head. It would never know how Hardy Ballington would fare at 24 hours, or when faced with the faster but older Hayward.

Author’s Note

I would like to thank Peter Lovesey for his help in researching the early history of the Ballington family. Also, thanks go to Paul Circosta who sent me the relevant pages of the now out of print Running on Three Continents and to Ian Champion who sent me The News of World Report on the 1937 London to Brighton race.

Sources

- Glorious Run by Young South African – Joe Binks News of the World 23 May 1937

- The World’s Greatest Long Distance Runner is a South African – P Craig – The Referee – Sydney, Australia 08 July 1939

- Running on Three Continents – Arthur Newton 1940

- Recollections of my attempt on the 100 mile record – Hardy Ballington 11 October 1968

- The Comrades Marathon Story – Morris Alexander 1985

- Lore of Running – Professor Tim Noakes 1987; 2003

- Hardy endeavours which led to 1000 km a month – long before Emil thought of it – A Ballard Peck TRACKSTATS March 2003