Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 31:37 — 38.8MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

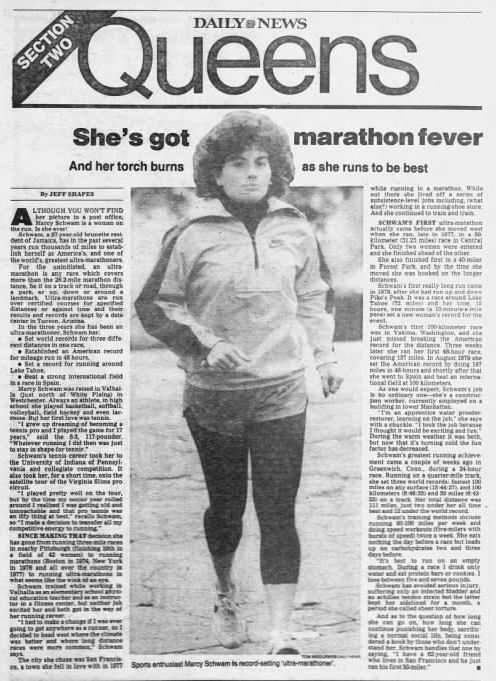

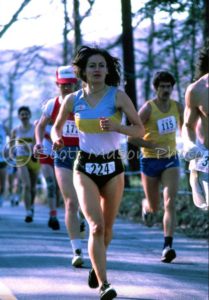

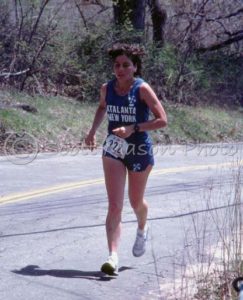

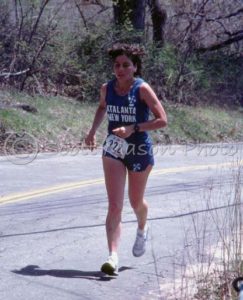

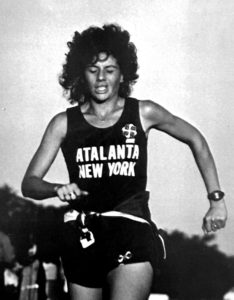

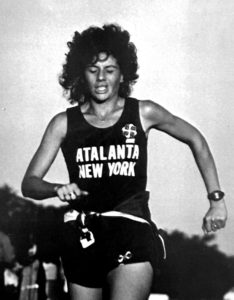

Marcy Schwam (1953-) from Massachusetts, was an ultrarunning pioneer in the 1970s and early 1980s, during an era when some people still believed long-distance running was harmful to women. She won about 30 ultramarathons and set at least six world records at all ultra-distances from 50 km to six-days. She was the third person inducted into the American Ultrarunning Hall of Fame.

Marcy Schwam (1953-) from Massachusetts, was an ultrarunning pioneer in the 1970s and early 1980s, during an era when some people still believed long-distance running was harmful to women. She won about 30 ultramarathons and set at least six world records at all ultra-distances from 50 km to six-days. She was the third person inducted into the American Ultrarunning Hall of Fame.

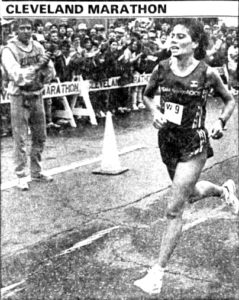

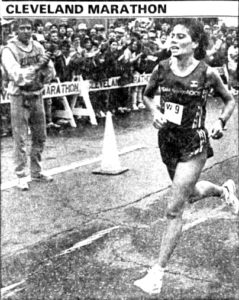

She was bold, brazen, with an impressive “get-out-of-my-way” attitude and racing style. She would take command of a race and preferred to lead rather than follow. This courageous attitude also helped to break through the stigma held against women runners of the time. She dared to be the only woman in a race. She inspired many other women to get into the sport and reach high.

Schwam trained hard and raced hard. She always knew what she was doing. Ultrarunning historian, Nick Marshall, observed, “She set lofty goals for herself and she was gutsy enough to go after them with wild abandon. She might soar, or she might crash, but either way it was going to be a maximum effort.” She thoroughly enjoyed competitive racing, where limits were explored and tested often.

Marcy Schwam was born in 1953, in New York City. Her parents, Stanley Schwam (1924-) and Irma (Weisberg) Schwam (1928), were both long-time residents of the City. Stanley worked in the women’s undergarment industry for 57 years. During the 1950s, the family lived in the Bronx but later moved to Valhalla in the suburbs.

Schwam’s ancestry was Polish. Her grandparents and her father were Jewish immigrants who came to the United States from Poland during the early 1900s before World War II. They worked hard and successfully supported and raised their families in the big city.

Early Years

At the early age of five, Schwam started to take up tennis and dreamed of becoming a professional tennis player. Her father commented, “Marcy never walked anywhere. She was in constant motion all the time. She was also very competitive. If she lost at Monopoly as a kid, she wouldn’t talk to you for a week.”

In high school, she was very athletic and played basketball, softball, volleyball, field hockey and even lacrosse. She did some running, but it was just a way to stay fit for tennis. To her, there was nothing else in the world that counted except playing tennis.

From 1971 to 1975, Schwam attended Indiana University of Pennsylvania (IUP) where she eventually received a bachelor’s degree in Health and Physical Education. (Later she also worked on a master’s degree in Exercise Physiology at Adelphi University and San Francisco State). At IUP, She became a member of the tennis team, excelled, and became ranked number one in the state.

First Running Races

Schwam started running some races in 1972 at the age of 21. She explained, “As a sophomore in college in 1972, I ran a 3-mile race in Pittsburgh. I was on the tennis team and a friend on the cross-country team talked me into it. I was running to and from tennis practice and someone dared me to run the Boston Marathon.”

In 1972, the Boston Marathon opened their race to women for the first time. Schwam entered the next year in 1973, a true pioneer women’s distance runner. The Boston Athletic Association sent entrants blue or pink entrant postcards depending on their gender and sent her a blue card with the name Marc. Apparently, they just couldn’t get used to the fact that women were running marathons. It took effort getting that corrected at check-in. She was one of only 12 women to run, finished in 4:50, and said, “I really wanted to prove that women could do these types of things. There was such a stigma about women and long-distance running that needed to be proven false and I took that upon myself to do.”

Competitive Tennis

But tennis was still Schwam’s main sport. In college, she dominated playing both singles and doubles. In 1974, the 14-member team that she captained went undefeated in team competition.

Their match record for the season was an astonishing 59-1. March’s all-time singles record at IUP was 35-1. It was written that her team “pummeled opponents like a ruthless heavyweight champion, always winning by a knockout, never showing mercy. A case could even be made that the 1974 team most dominant team in school history, regardless of sport. Not only did the Indians win fifty-nine of sixty singles and doubles matches that fall; they took 118 of 124 sets. The challenge facing foes was comparable to climbing Everest in a howling blizzard.”

After graduation in 1975, Schwam headed to Florida during the summer to play the tennis circuit, hoping to break into the professional ranks. She did play well for a while on the Virginia Slims circuit in Brownsville, Texas. But she quit by the next year. She said, “I didn’t like the other players. They were just spoiled-brat kids, and when I realized these were the people I was going to travel with and spend time with, I decided that it just wasn’t for me.”

It was hard for her to leave tennis after 17 years of playing, but she knew she was burned out and ready for something new. She also admitted, “I realized I was getting old and un-coachable, and that pro tennis was an iffy thing at best. I made a decision to transfer all my competitive energy to running.” She left work as a tennis pro and moved on to be a physical education teacher and fitness instructor.

Early competitive running 1976-77

In 1977, at the age of 24, Schwam started to really concentrate on running marathons and finished a total of twelve all over the country, including Boston, where she finished in 3:40:04. When she finished marathons and continued to improve her times, she realized that she wasn’t exhausted at the end of her races. She said, “Maybe I wasn’t running them hard. Anyway, I was having no problems with endurance.” She was ready to run further.

The State of Women’s Ultrarunning

In the 1970s, the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU), was governing American amateur running and working to prepare athletes for the Olympics. By 1975, an AAU Women’s Track and Field committee existed, but they still held the view “1500 meters was perhaps even a bit too far for the fragile female athlete.”

Prior to 1976, in the modern era of ultrarunning, there were only a few (about 20) American women who ran ultras, including:

- Donna Aycoth (1950-) – the first woman to finish the JFK 50, in 1968, with 10:41 at Maryland

- Eileen Waters (1945-2016) – the first woman to break seven hours running 50 miles in 1974, at Santa Monica, California.

- Miki Gorman (1935-2015) – the first woman of the modern era to run 100 miles is less than 24 hours, in 1970, with 21:04:04, indoors at Los Angeles, California

- Natalie Cullimore (1937-) – who ran 100 miles in 16:11, in 1971 on a road loop at Rocklin, California.

Women were welcome to run in American ultrarunning events during the 1970s, but there were very few who entered because the door had only recently opened for them to run marathons. In 1977, only abut 40 women finished American ultrarunning events.

By the mid-1970s, women’s ultrarunning “records” were just starting to be recorded and ready for the pioneers to claim. In 1976, the known women’s world best times on track or road were:

- 50 km: 4:11:58

- 50 miles: 6:55:27

- 100 km: 7:50:37

- 100 miles: 16:11

- 24-hours: 106 miles

First Ultra

Clearly, Schwam had talent for the ultra-distances. A few months later, in June 1978, she competed at the Forest Park 40 Mile race in Queens, New York, on a four-mile loop. She finished first with an impressive 5:54:15. Her parents attended and “stood shaking their heads” not understanding why she was competing in these long races. After that race, Schwam was determined to concentrate on ultras. Her mother became very supportive and became her greatest fan.

When Schwam was asked if any female long-distance runners inspired her to become interested in running ultras, She said, “There were no real inspirations, and after all, there weren’t many women running ultras back then. If these people existed, we probably didn’t know about them.”

Empire State Building Run-Up

Climbing the stairs of the famed building had a long rich history. In 1932, the Polish Olympic skiing team bound for Lake Placid, New York, made a climb. In 1939, the Yale track team worked out on the stairs. In 1933, King Kong, of course, scaled the building but took the exterior route.

The 1978 runners wore race shirts with the picture of King Kong. All the competitors had ultrarunning experience, previously running at least a 50K. They had to sign releases freeing the building’s management from any medical liability and all agreed that “you have to be a little wacky to be here in the first place.” Doctors were on the 23rd and 65th floors.

The event was the idea of Fred Lebow (1932-1994), the president of the New York Road Runners Club, who greatly supported ultrarunning in this early era. For this race, Lebow said, “Running up the building is like running up a great mountain. It’s an irresistible attraction because it is so visible in the Manhattan sky.” Schwam said, “It seems so big and beautiful, such a gigantic thing to do.” She admitted that she was a bit scared.

Ted Corbitt (1919-2007), “the father of American ultrarunning,” fired the starter pistol. Gary Muhrcke (1941-) the eventual overall winner surged past the others around the 10th floor. He had had previously won the first New York City Marathon, in 1970, in 2:31, and had recently placed 3rd at the iconic London to Brighton 52-mile race. He reached the top of the building in 12:32. Schwam, who was a fitness instructor at that time in Ossining, New York, was the women’s winner with 16:03, placing 10th overall. She had been training about 80 miles per week and said, “My calves hurt a little bit. You need good thighs and you have to pick up your legs much higher. But it wasn’t as hard as I thought it would be.” The finishers received gold and silver statues of the Empire State Building.

Moving West

Lake Tahoe 72-miler

She next traveled to Lake Tahoe, to run the longest race of her career thus far, the Lake Tahoe 72-miler. In the early 1960s relay teams would run the 72-miles around Lake Tahoe. In 1966, it was formalized into a seven-man relay race. The US Olympic team set the standard in 1968 of 6:55. In 1970, an astonishing 42 teams competed, and the record was lowered to 6:50. By 1975, ultrarunners started running the course solo and an annual race was started.

In 1978, Fifty-six solo ultrarunners showed up, including Schwam, for the hilly road race on the California/Nevada border. She wanted to become the first woman ever to finish the race. “I raced Sally Edwards (1948-), founder of Fleet Feet, for 45 miles. We were shifting back and forth. Then she was forced to slow down because of knee and hip pain. I actually started feeling strong from 50 miles to the end.”

Schwam finished first, tenth overall with a time of 12:01:32. Edwards was second with 13:15:15. Schwam said, “That race was really where it all started in terms of becoming competitive within the ultra community. The run around Lake Tahoe got me hooked and I gave up all plans for a real job and real career in search of the next challenge.”

For the next year, 1979, Schwam ran in all the ultras that she could find in the west. “I was running one about every month just because they were there to run, and I got carried away with it.” In early May, she thought she broke the American 100 km record in Yakima, Washington, by nearly 20 minutes, with a time of 8:51:09. But later it was discovered that on the same day, a few hours earlier, Sue Ellen Trapp (1946-) had run a 100 km in 8:43:14 at Lake Waramaug, Connecticut. That would not be the last time they competed for records. They never raced head-to-head against each other, but were very aware of the juggling of American records taking place between them and with Sandra Kiddy (1936-2018) too. They tried to outdo each other, “but the mutual respect for one another always remained.”

48-hour races at Woodside, California

While living in San Francisco, Schwam got to know ultra-legend Don Choi (1948-), who had run about 20 ultras by 1979. Schwam said, “We were great pals. We would train together on Sundays at the Polo Grounds track, sunrise to sundown, nine hours.” Her running friend, Jackie Stack, niece of ultra-pioneer, Walt Stack (1908-1995), would bring them food to support their crazy all-day 50-mile training runs. Schwam said about those loopy runs, “I have to admit that I was losing my mind there for a while. I was a real basket case.” They would often run 140-mile weeks.

In May 1979, Choi put on the first modern-era 48-hour race on a track in Woodside, California. It was named “David Copperfield Track Ultramarathons.” Schwamcompeted in this historic race and was interested it going after the long-standing 24-hour world record of 106 miles. Twenty runners competed on the track. She did not get the 24-hour record, but did set the first modern-era women’s 48-hour world record of 137 miles. (In 1880, Amy Howard (1862-1885), of New York City, reached 165 miles in 48 hours). Choi established a modern-era 48-hour men’s record of 204 miles. (In February 1882, Charles Rowell (1852-1909) of England, ran 258.3 miles in 48 hours).

A few months later in August, Choi put on another 48-hour race on the Woodside track which he called, “Daniel Boone/Lorna Doone Ultras.” Schwam was the overall winner for the 24-hour race, setting a women’s world record of 113 miles. She then continued on to reach 146 miles in 48 hours, for another modern-era record. Her 100-mile time was 19:03:06 and her 200 km time was recorded to be 27:52:26, establishing the first known women’s world best for that distance.

Choi put on yet another 48-hour race on the track in December. Schwam ran again, but all the runners quit by 36 hours because of a torrential downpour that terribly flooded the track. She reached 87 miles.

Trails

While in California, Schwam started to run on trails. She discovered that running on trails was easier on her body. “On the road, when you start hurt, it’s hard to take the hurt away.” She had trained many miles on trails, including on the Western States 100 course. She signed up for the 1979 Western States 100, the second year the race was held and actually 89 miles. But she did not start because some nagging injuries got in the way. She explained, “A good time was out of the question. I didn’t want to put in the time schlocking in just to be able to say I’d finish.”

But Schwam still preferred to race on roads and tracks. “I enjoyed the security of a track, knowing where you were all the time. Even on the roads, I preferred shorter loops, a mile or two, rather than longer loops.”

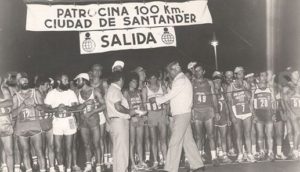

Spain in 1980

In 1980, Schwam moved back to New York and took a job as a construction worker, employed working on buildings in lower Manhattan. She chuckled, “I’m an apprentice water-proofer, learning on the job. I took the job because I thought it would be exciting and fun.” She would waterproof the outside of buildings, caulking windows while up on scaffolding as high as 50 stories up. This job gave her time to run between 80 and 100 miles per week.

The race was the International 100 km of Cantabria in Santander, Spain, on a hilly road course. She was the only woman in the race, but competed against 75 men. She finished 13th overall with 8:24:53, lowing the American 100 km road record.

Three World Records

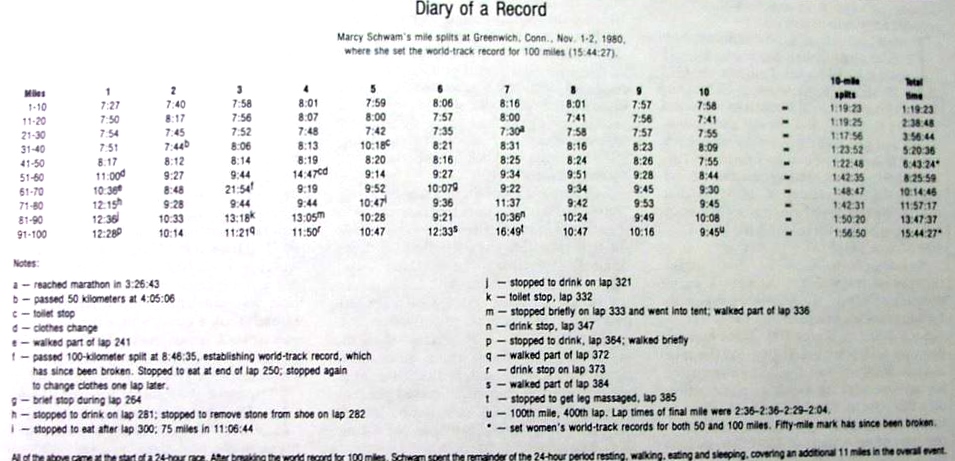

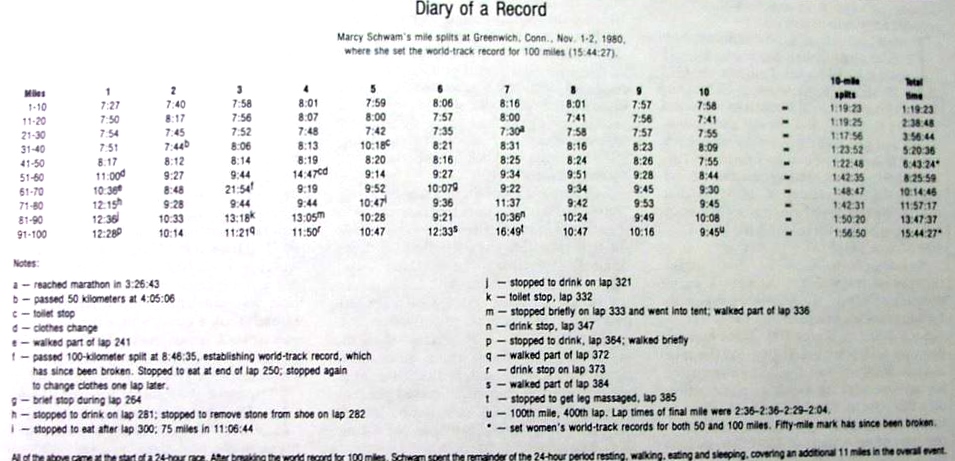

Late in 1980, a 24-hour race to be held on the East coast, was cancelled. The Sri Chinmoy Marathon team quickly, within one week, put together a replacement race held November 1, 1980 on a cinder track at Greenwich, Connecticut. They found an old abandoned track behind the city hall, which they raked, cleaned, and measured. It was slightly less than a standard 440-yard track. Ted Corbitt approved the measurements. Six runners, including Schwam, started this chilly race, with Ted Corbitt firing the gun.

She slogged on into the chilly night and smashed the 100-mile world record set by Natalie Cullimore in Rocklin, California, back in 1971 of 16:11:01. Schwam’s time was 15:44:27. She had lapped every man in the race more than 80 times. “As soon as I reached 100 miles, I stopped immediately. I was totally thrilled when I got the 100-mile record. It was a great relief. The pain ended my effort right there. The 24-hour record (123 miles) was out. I tried walking with blankets around me, just trying to move around the track, but it was nothing I could control. My whole body was one big spasm. I never hurt so much in my life.” Over the last eight hours, she only covered another 11 miles for a total of 111 miles. With her three world records, she earned a Nurmi Award from Runner’s World as the best female ultramarathoner of 1980.

Training

Schwam was described as being 5-foot-3 and 115 pounds. “She does not look the part of a typically bone-thin long-distance runner. But training, year round, she does act the part.” Her typical day began at 3:45 a.m. with a ten-mile run along the Hudson River. She then would commute to the City for her construction worker job that began at 7 a.m. After work, she would go out for another run.

For race preparation, she wouldn’t eat much the day before a race. She would eat a light breakfast and drink a lot for coffee during the day. She liked to feel lighter and usually was too nervous to eat anyway. She would taper down her miles training leading up to race, but would usually run every day, even on the day before a race.

Despite her wins and records, Schwam didn’t get a lot of recognition for her accomplishments outside of her local ultra community. She said, “I’m still pretty much unknown. I am not very good at self-promotion. I’m more of a quiet, private person. I do what I’m doing because I like it. It is self-gratifying. I’m proud of my results, but I don’t even keep the trophies I win. I have no need for them.”

She mostly ran ultras because of the mental challenge and said, “When people ask, ‘why do you run 100 miles,’ and when I explain that it’s just because it is such a mind challenging thing, that’s hard for people to relate to. I like conquering myself.”

Lake Waramaug 50-miler

The Lake Waramaug 50-mile and 100 km race in Connecticut started in 1974. The course was fast on a 7.59-mile paved road loop around the lake. Runners ran 50 miles and then could decide if they also wanted to continue on, to finish the 100 km race. For many years, it was the unofficial national championship for the 100 km distance. Schwam focused on running the 50 miler there in 1981, hoping to break Sue Ellen Trapp’s world record of 6:12:12. One of England’s premier female ultrarunner, Leslie Watson, the reigning champion of London to Brighton, came over to compete. The race between the two turned out to be classic.

Schwam felt very confident and ready for the May 1981 race. She started fast and decided to go for broke, while her British rival paced more conservatively. Nick Marshall wrote, “Schwam roared through the marathon mark in 3:04, opening up almost a mile gap by that point, and hit the 50 km mark in 3:39. She became only the fourth woman to ever break 3:40.” Schwam developed severe blisters and slowed. Watson passed her by mile 40 and went on to claim a new world record of 6:02:37. Schwam finished in 6:13:09. She said, “That race was one of the biggest crushes of my career. I had no doubt I could break six hours and being stopped by blisters was very disappointing.”

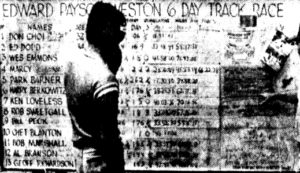

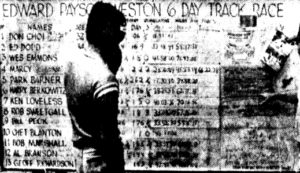

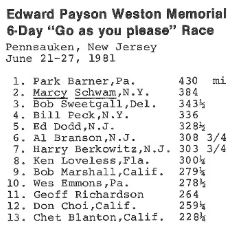

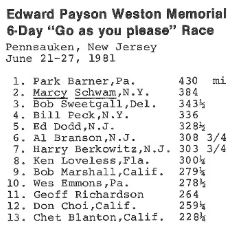

Weston 6-day Race

Just a few weeks later, she ran in the International Women’s Marathon in Ottawa, Canada and went under three hours for the first time, finishing in 2:50:50. She set her marathon PR in October 1982 at the New York Marathon with 2:48:17.

Spain Again

Ultrarunning Magazine described her accomplishment as a “landmark performance for the ages.” She learned a lot from the race, “I realized that speed and ultra could be used in the same sentence.” She held this American record until Ann Trason broke it in 1988.

Move to Massachusetts

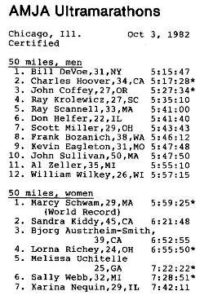

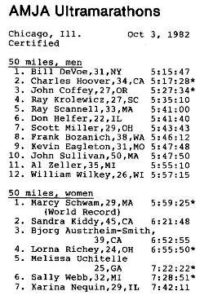

AMJA Championship at Chicago

Elite American ultrarunners of the 1980s flocked to the AMJA (American Medical Joggers Association) Ultras to compete each year of 50-miles or 100 km. This race was in Chicago, with the start in between two out-and-back 5-mile “loops” through a park and along the Lake Michigan shoreline. It became one of the largest ultras in the country. The course was flat as a pancake and gave spectacular views of Lake Michigan and the Chicago skyline. For several years, including 1982, it was the RRCA (Road Runners Club of America) National Championships. World and American Records were set in this race, held yearly. In 1980, Barney Klecker set a world record on the course for 50 miles with 4:51 and in 1981 Bernd Heinrich set the American 100 km record of 6:38:20.

Nick Marshall observed that Schwam was cool and confident a couple of days before the big race. “Her whole attitude was an upbeat one of being well-prepared and very much in command of the situation. She believed that even if she ‘fouled up’ and didn’t make it at this race, she would get it at another”. Her 50-mile personal best up to that point was 6:13, and the world record was still held by Leslie Watson at 6:02.

On race day, with 273 starters, Schwam “attacked the lakefront circuit from the gun.” As she was running, they sent a guy out on a bicycle to keep everyone out of her way. She reached the marathon mark in an astonishing 2:53. By mile 30, she slowed and she had to walk for briefly before mile 40. She refused to let her goal slip away. With 9.5 miles left, she had 75 minutes before the six-hour barrier. “Those last miles at 7:40 pace were tough, but Schwam had been so close to the record before, that she couldn’t falter yet again.” With three miles to go, she kicked up the pace, dodged bicycles, and finished with a 5:59:26 a new world record. She said, “Being the first female to break six hours for 50 miles is probably the thing I’m most proud of.”

Awards

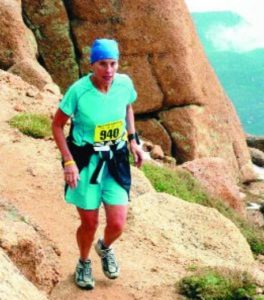

![]()

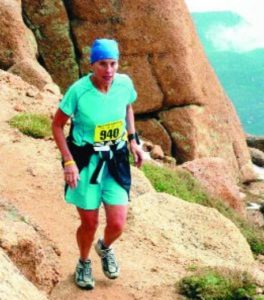

![]()

Marathons

Injury

In June 1983, she went to run the TAC 100-Mile Championship held at Shea Stadium in Flushing Meadows, New York. Unfortunately, she dropped out at 15 miles with a severe planters fasciitis in her foot. Donna Hudson went on to break the 100-mile world record with 15:31:57. Schwam’s injury also scratched her from running another six-day race in July at Downing Stadium in New York where Lorna Richey took away her modern-era American six-day record, reaching 401 miles. Schwam healed for three months and started racing marathons again in September.

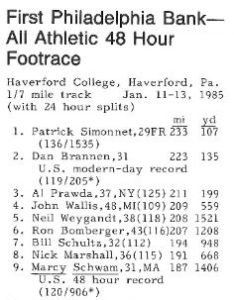

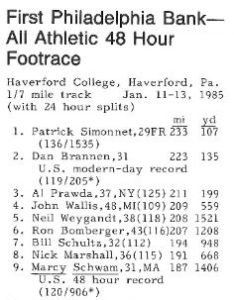

Haverford Indoor 48 Hours

1984

In May 1984, Schwam achieved one of her goals. She ran in the very first Olympic Marathon Trials for women in Olympia, Washington. She placed 181st with 3:03:40.

Ultrarunning career concludes

After 1984, at age 32, Schwam’s highly competitive ultrarunning career started to wind down. She ran 245 kilometers (152 miles) at the 1985 World 48-hour Championship at Montauban, France, where Yiannis Kouros set a mind-blowing world record of 287 miles. In 1986 she ran Western States 100 and finished in 25:12:57. Her marathon speed remained, and she continued to crack the 3-hour mark. After 1988, she left ultrarunning races for a while.

In 2001, Schwam was inducted in the Indiana University of Pennsylvania Athletic Hall of Fame recognized for both her tennis achievements and ultrarunning dominance. Schwam was also inducted into the American Ultrarunning Association Hall of Fame in 2005, recognizing her pioneer efforts for women in ultrarunning along with her amazing running accomplishments. She had knee surgery but was determined to not let that slow her down. She took up snowshoeing races, which she became very involved in for many years. She continued to find job opportunities to keep her close to the endurance sport. In 2006, she was Reebok’s director of global walking.

She said in 2020, “I’ve been running for well over 50 years. I have a knee that bit the dust. My mind and endurance still want to do long races, but the knee would let me. I love mountain racing and snowshoe races. Short trail races now satisfy my competitiveness, even if only against myself.” In 2023, she covered 80 miles in the Hamsterwheel 24-hour run race held in New Boston, New Hampshire.

In 2024, Marcy Schwam was 71 and lived in Marblehead, Massachusetts. She was a Saucony Trail Ambassador and an Ultraspire Athlete Ambassador.

Marcy Schwam’s Personal Records

- One mile: 5:17

- 10 km: 35:44

- Marathon: 2:48:17

- 50 Miles: 5:59:26

- 100 km: 7:47:28

- 100 Miles: 15:44:28

- 24 Hours: 124 Miles

- 48 Hours: 187.8 Miles

- Six Days: 384 Miles

Sources:

- Ultrarunning Magazine, Jun, Sep 1981, Oct, Nov, 1982, Jan, Mar 1984, Jan, Mar 1985, Apr 2000, Oct 2016

- The Indiana Gazette (Indiana, Pennsylvania), Oct 16, 1973, Nov 25, 1974, Mar 28, 1981, Mar 2, 1983, May 12, 1984

- IUP’s All-time Most Dominant Team

- Poughkeepsie Journal (New York), Nov 27, 1976

- Fort Lauderdale News (Florida), Dec 4, 1977

- Asbury Park Press (New Jersey), Feb 17, 1978

- A History of the Empire State Building Run-Up

- Great Falls Tribune (Montana), Feb 17, 1978

- Pikes Peak Marcy Schwam times

- Runners World, “On the Trail with Marcy Schwam”, Jun 5, 2007

- Auburn Journal, Jul 6, 1979

- Andy Milroy, The Long Distance Record Book

- Sri Chinmoy Marathon Team website

- Daily News (New York, New York), Nov 3,14, 1980, Jun 19, 1983, Jul 10, 1984

- Nick Marshall, Ultramarathon Summary, 1978, 1981, 1982

- The Philadelphia Inquirer (Pennsylvania), Mar 25, 1981, Jan 16, 1984

- The Miami Herald (Florida), Dec 17, 1982

- The Akron Beacon Journal (Ohio), May 16, 1983

- Nick Marshall early results

- Nick Marshall, Runner’s World Quarterly, “Marcy Schwam,” 1981

- The Desert Sun (Palm Springs, California), Jul 4, 1984

- The Pantagraph (Bloomington, Illinois), Jan 14, 1988

- Mark Dorion, Ultrarunning Magazine, Apr 2000, “The Incredible Marcy Schwam: US Ultrarunning Pioneeer”

- ATRA, “Marcy Schwam: Pioneer of Women’s Ultrarunning”