Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 33:40 — 41.8MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

This is the second part of the Dave Kunst story. Read/Listen/Watch to Part 1 here.

This is the second part of the Dave Kunst story. Read/Listen/Watch to Part 1 here.

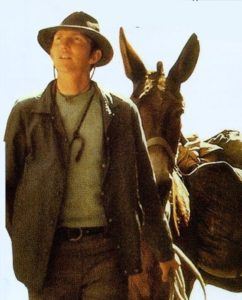

Dave Kunst, originally from Minnesota, now from California, claims that he was “the first person verified to have completed circling the entire land mass of the earth on foot.” Kunst’s 1970-74 walk has historic importance for the modern-era of ultra-distance walking. I believe that Konstantin Rengarten was actually the first in 1894-1898 (See Part 3). I will show that Kunts’ “verified” claim is dubious, but his amazing walk did happen, and the story is fascinating and exciting. But at what cost to those who believed in him? With the end just days away, everything seemly fell apart.

In 1970, Dave Kunst of Waseca, Minnesota, started a walk around the world with his brother John. Part 1 of this story covered their travels east to New York, by plane to Portugal, and then on foot with a mule to Afghanistan where John was shot and killed by bandits. Dave was wounded and returned to Minnesota to recover in November 1972.

Dave felt strongly that the walk should be continued, and he deeply wanted to get back on the road to experience an exciting and free life, without family, job, or financial obligations. He said, “The walk will definitely go on. I want to keep the ball rolling. I will be back to finish what my brother and I started so he will not have died for nothing.”