Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 30:47 — 37.0MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

You can read, listen, or watch

Professional ultrarunners/pedestrians of the late 1800s and early 1900s were constantly looking for endurance races or head-to-head matches to prove their abilities and make significant amounts of money. During the mid 1880s, some of them, including popular black ultrarunner Frank Hart, changed out their leather running shoes for roller skates during periods of endurance rolling skate fads.

Professional ultrarunners/pedestrians of the late 1800s and early 1900s were constantly looking for endurance races or head-to-head matches to prove their abilities and make significant amounts of money. During the mid 1880s, some of them, including popular black ultrarunner Frank Hart, changed out their leather running shoes for roller skates during periods of endurance rolling skate fads.

While not technically ultrarunning, the emerging six-day roller skate races mirrored significantly the six-day foot races that had become the most popular spectator sport for several years in the United States. Why not put wheels on those ultrarunning feet and see what could be done? The results were fascinating, and in 1885 the Boston Globe left behind very detailed play-by-play results that revealed what these unique races were like. How many miles could an extreme endurance athlete skate in six days on primitive rolling skates?

| The Ultrarunning History Podcast is included in the People Choice podcast awards in the history category. Please help me by voting for the Ultrarunning History Podcast. During July 2021, go to https://podcastawards.com to register and nominate “Ultrarunning History” in the “History” category. Thanks! |

Early Roller Skating

Roller skating was thought to be invented as early as 1735 by John Joseph Merlin of Belgium. It was said that while showing off his new wheeled shoes at a party in London, that he crashed into a mirror. In the early 1800s roller skates were introduced in isolated cases into the theater as an alternative to ice skating performances. In 1854 a French company performed “La Prophet” in New Orleans, Louisiana, and the entire ballet of one hundred performers appeared on roller skates.

In 1863, the four-wheeled roller skate, or quad skate, was invented by James Leonard Plimpton making it possible for amateurs to participate. The first public roller rink was opened in 1866 by Plimpton in New York City, who also introduced a roller skating academy. At first, he did not mass-market his patented skate and would only let them be used in rinks with maple floors.

Cities including Cincinnati, Ohio and St. Louis, Missouri, opened roller rinks. The main worries were that participants would be careless about their attire and would over-exert themselves. “It is true that roller skating is an exercise which soon throws practitioners into a furious perspiration, but it is an established fact that after a person has become even moderately skilled, and does not get excited and confused, there are hardly more perspiration and fatigue induced than are found in a gentle ramble in the shade.”

Cities including Cincinnati, Ohio and St. Louis, Missouri, opened roller rinks. The main worries were that participants would be careless about their attire and would over-exert themselves. “It is true that roller skating is an exercise which soon throws practitioners into a furious perspiration, but it is an established fact that after a person has become even moderately skilled, and does not get excited and confused, there are hardly more perspiration and fatigue induced than are found in a gentle ramble in the shade.”

There was also concern that participants would “find their feet have gone off in an unexpected radiation from a common centre.” Many thought the practice was immoral. “Does it improve a young girl’s modesty or morals to fall in a heap on a skating rink floor, in the gaze of hundreds, with perhaps her feet in the air and her clothes tossed over her head? Is it good for her proper training to see other females in such plight?”

There was also concern that participants would “find their feet have gone off in an unexpected radiation from a common centre.” Many thought the practice was immoral. “Does it improve a young girl’s modesty or morals to fall in a heap on a skating rink floor, in the gaze of hundreds, with perhaps her feet in the air and her clothes tossed over her head? Is it good for her proper training to see other females in such plight?”

The Six-Day Race

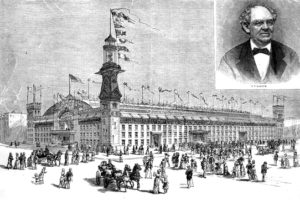

On March 1, 1875, P. T. Barnum, of circus fame, put on the first formal six-day foot race in America, held at his Hippodrome in New York City. It was a $5,000 match race between Edward Payson Weston and Professor Judd. Weston reached 431 miles during that first American six-day race.

On March 1, 1875, P. T. Barnum, of circus fame, put on the first formal six-day foot race in America, held at his Hippodrome in New York City. It was a $5,000 match race between Edward Payson Weston and Professor Judd. Weston reached 431 miles during that first American six-day race.

Six-day cycling started three years later in 1878, in England, with a race between seven competitors held in the Agricultural Hall in London. It was won by W. Cann of Sheffield who reached 1,060 miles. Riders were only allowed to ride 18 hours each day.

Six-day cycling started three years later in 1878, in England, with a race between seven competitors held in the Agricultural Hall in London. It was won by W. Cann of Sheffield who reached 1,060 miles. Riders were only allowed to ride 18 hours each day.

The first known six-day skating match was held from May 5-10, 1879, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, between three skaters, won by Mayer with 685 miles.

Into the 1880s, the roller rinks became very successful. In Buffalo, New York, there were at least ten major roller rinks. It was said “If you see a man on the street with a green bag under his arm, no longer set him down as a lawyer. Ten to one he is a professor of roller skating.” But the rolling success brought more criticism. Owners of billiard rooms lost significant business to the roller rink craze. Doctors expressed opinions that “the exercise was injurious to the health.”

Into the 1880s, the roller rinks became very successful. In Buffalo, New York, there were at least ten major roller rinks. It was said “If you see a man on the street with a green bag under his arm, no longer set him down as a lawyer. Ten to one he is a professor of roller skating.” But the rolling success brought more criticism. Owners of billiard rooms lost significant business to the roller rink craze. Doctors expressed opinions that “the exercise was injurious to the health.”

Long Distance Roller Skating

Soon long-distance roller skating competitions were established. In 1883, a ten-mile roller skating match was held in Laconia, New Hampshire with a purse of $50 between Charles H. Ladd (1865-1888) and Albert C. Whittier at the Casino Rink. Ladd won by six seconds with a time of 59:50. By 1885, the ten-mile record had been lowered by a Swede named Pauleus at New York City, with a time of 37 minutes.

Soon long-distance roller skating competitions were established. In 1883, a ten-mile roller skating match was held in Laconia, New Hampshire with a purse of $50 between Charles H. Ladd (1865-1888) and Albert C. Whittier at the Casino Rink. Ladd won by six seconds with a time of 59:50. By 1885, the ten-mile record had been lowered by a Swede named Pauleus at New York City, with a time of 37 minutes.

The skates included wooden wheels. Ball-bearing roller skate wheels were not invented until in 1884 and probably were not used in mass until 1886, so the friction made skating for long distances in the early races hard and slow. In 1884 the first known six-day roller skating race was held in Boston, limiting skating to twelve hours per day. Kenneth A. Skinner, 25, of Boston held off Eugene Maddocks (1861-1924), also of Boston, for the win in 731 miles. Charles W. Emery (1862-1934) of Morristown, New Jersey set a ten-hour record of 117 miles at Trenton, New Jersey on April 10, 1884.

The skates included wooden wheels. Ball-bearing roller skate wheels were not invented until in 1884 and probably were not used in mass until 1886, so the friction made skating for long distances in the early races hard and slow. In 1884 the first known six-day roller skating race was held in Boston, limiting skating to twelve hours per day. Kenneth A. Skinner, 25, of Boston held off Eugene Maddocks (1861-1924), also of Boston, for the win in 731 miles. Charles W. Emery (1862-1934) of Morristown, New Jersey set a ten-hour record of 117 miles at Trenton, New Jersey on April 10, 1884.

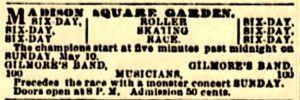

1885 Six-Day Race at Madison Square Garden

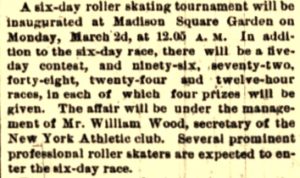

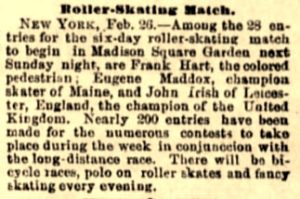

In February 1885, a six-day skating tournament was announced to be held March 2-8, 1885, at Madison Square Garden. The idea was conceived by Colonel Garnet and would under the management of William Wood, the secretary of the New York Athletic club. Champion skaters signed up to compete, and the field also included some Pedestrians (ultrarunners). Frank Hart (1858-1908), a celebrated black champion six-day pedestrian brought his running endurance talents to the event. The winner would receive $500 ($14,000 value today) and a diamond belt valued at $250.

In February 1885, a six-day skating tournament was announced to be held March 2-8, 1885, at Madison Square Garden. The idea was conceived by Colonel Garnet and would under the management of William Wood, the secretary of the New York Athletic club. Champion skaters signed up to compete, and the field also included some Pedestrians (ultrarunners). Frank Hart (1858-1908), a celebrated black champion six-day pedestrian brought his running endurance talents to the event. The winner would receive $500 ($14,000 value today) and a diamond belt valued at $250.

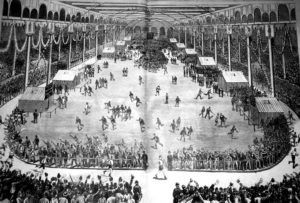

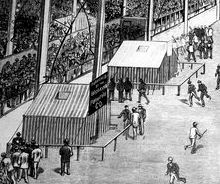

Excitement increased as the event approached. The Boston Globe reported, “The arrangements for the great international six-day race carnival and tournament on roller skates at Madison Square Garden are completed and will constitute the greatest enterprise of its kind ever attempted in the annals of amusement. The entire surface of the Garden has been transformed into the largest rink in the world, with an excellent skating surface, skate rooms and appropriate offices erected and provided with a track twenty feet wide. It is believed that at least ten men will cover 1,000 miles in six days.”

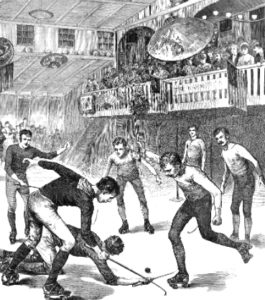

Many entertaining side-shows were planned to be held during the race including, backward racing, sack races, orange races, acrobatic skating, dancing on skates, stilt skating, Roman games on rollers, rope skipping on skates, polo on skates, bean races, egg races and potato races.

The old original Garden was well decked out. “It was gorgeous with flags and bunting. Boxes were wound and festooned with evergreen, and banners and coat-of-arms decorated the great pillars. The track was the usual eighth of a mile circle around the inside of the box tier and was fenced in with stout pickets on either side.”

The old original Garden was well decked out. “It was gorgeous with flags and bunting. Boxes were wound and festooned with evergreen, and banners and coat-of-arms decorated the great pillars. The track was the usual eighth of a mile circle around the inside of the box tier and was fenced in with stout pickets on either side.”

The inside of the track was reserved for the exhibitions. A group of thirty-two lap counters were stationed by a tall mahogany clock at the north side of the Garden. They transmitted their figures through a speaking tube to a person maintaining an immense scoreboard that was updated once per hour. Most of the skaters brought two handlers or trainers with them. On the east end of the Garden skater apartments were fenced off for the skaters and their crew to sleep, but it was expected that only one-third of the starters would need them, that the rest would drop out early. Skaters could also retire to a room in nearby Putnam House for an extended break.

The inside of the track was reserved for the exhibitions. A group of thirty-two lap counters were stationed by a tall mahogany clock at the north side of the Garden. They transmitted their figures through a speaking tube to a person maintaining an immense scoreboard that was updated once per hour. Most of the skaters brought two handlers or trainers with them. On the east end of the Garden skater apartments were fenced off for the skaters and their crew to sleep, but it was expected that only one-third of the starters would need them, that the rest would drop out early. Skaters could also retire to a room in nearby Putnam House for an extended break.

Entrants

A few key entrants should be profiled.

A few key entrants should be profiled.

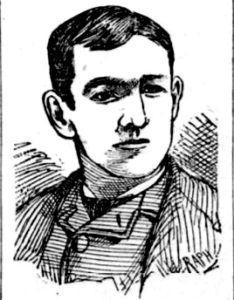

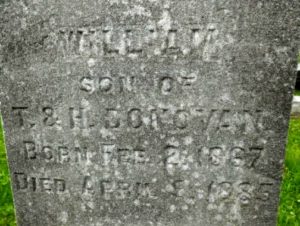

William Donovan

Willian Donovan, age 18, was from Elmira New York, a son of Irish immigrants. He was a newsboy and a shoemaker by trade. As roller skating started to become popular, he entered and won several short-distance matches and tried to turn professional. He heard about the six-day race and a few of his chums urged him to enter. He had no funds but said he would do it if he could come up with a skating outfit. One of his friends purchased a shirt for him and loaned him a silk handkerchief. Others gave shoes, caps, a belt, overcoat, and knee breeches. Seven dollars was raised for him to get him to New York. “Young Donovan on reaching New York was alone and friendless.”

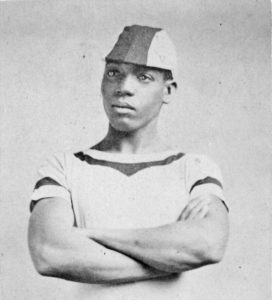

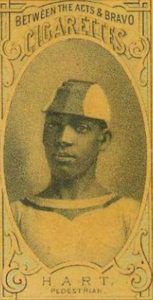

Frank Hart

Frank Hart (1858-1908), age 27, was a black Pedestrian. He was born in Haiti and his given name was Fred Hichborn, but he changed it when he became a professional athlete. He endured racial abuse and violent threats from hostile spectators. Some competitors refused to shake his hand at the starting lines. But Hart became one of the greatest ultrarunners of his time. In 1880 Hart won a six-day race, walking 565 miles in Madison Square Garden, earning him a fortune. He became wildly popular. But he burned through his winnings fast and continued to seek ways to win professional endurance awards.

Frank Hart (1858-1908), age 27, was a black Pedestrian. He was born in Haiti and his given name was Fred Hichborn, but he changed it when he became a professional athlete. He endured racial abuse and violent threats from hostile spectators. Some competitors refused to shake his hand at the starting lines. But Hart became one of the greatest ultrarunners of his time. In 1880 Hart won a six-day race, walking 565 miles in Madison Square Garden, earning him a fortune. He became wildly popular. But he burned through his winnings fast and continued to seek ways to win professional endurance awards.

Albert Schock

Albert Schock (1857-1921), age 28, was from Chicago, Illinois. He was 140 pounds and stood five feet, seven inches tall. He was an experienced ultrarunning pedestrian, a veteran of three six-day go-as-you-please running races in Chicago. He had performed well, finishing in second, third, and fifth place.

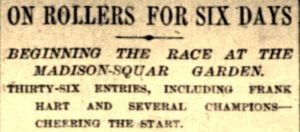

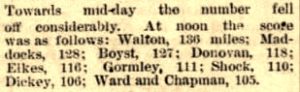

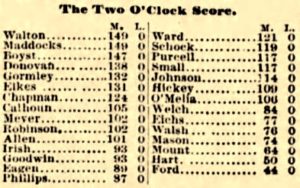

The Start

The historic six-day roller skating race started as planned at 12:05 a.m. on Monday, March 2, 1885, with thirty-six skaters, all under 30 years old. There were about 2,000 spectators on hand to witness the start. “The competitors came to the starting line and when at the signal all moved away together, amid the cheers of the crowd. The sight was very pretty. The first mile was made by Jacob A. Small, age 23 from Brooklyn in five minutes. The skaters kept together for several miles with Small in the lead. The positions of the others changing frequently.”

The historic six-day roller skating race started as planned at 12:05 a.m. on Monday, March 2, 1885, with thirty-six skaters, all under 30 years old. There were about 2,000 spectators on hand to witness the start. “The competitors came to the starting line and when at the signal all moved away together, amid the cheers of the crowd. The sight was very pretty. The first mile was made by Jacob A. Small, age 23 from Brooklyn in five minutes. The skaters kept together for several miles with Small in the lead. The positions of the others changing frequently.”

Gilmore’s Band played on a bandstand in the center of the floor. “Just as the band struck up the first melodious blast, the gentleman of the bass tuba fell through and was lost to sight.” The band did not miss a beat, finished the number and then moved to a safer place at the south side of the Garden.

When morning came, many skaters were off the track. How was the ultrarunner Hart doing? “Very few of the contestants appeared in good training and Frank Hart, the pedestrian seemed almost unused to the skates.” It was clear that he knew nothing about skating. “He lifts his skates as if they were snowshoes and seems to imagine that all he has to do is put his foot on the floor and he will go ahead. He has made several attempts to spurt, but becoming overbalanced, has given it up. He now plods around the track in the hope that the others will become tired out and give him the field himself.” After ten hours he was in dead last with 29 miles.

When morning came, many skaters were off the track. How was the ultrarunner Hart doing? “Very few of the contestants appeared in good training and Frank Hart, the pedestrian seemed almost unused to the skates.” It was clear that he knew nothing about skating. “He lifts his skates as if they were snowshoes and seems to imagine that all he has to do is put his foot on the floor and he will go ahead. He has made several attempts to spurt, but becoming overbalanced, has given it up. He now plods around the track in the hope that the others will become tired out and give him the field himself.” After ten hours he was in dead last with 29 miles.

Early injuries occurred. Jno. Goodwin, experienced a bad fall injuring his knee and hip when he tried to stop himself in front of a chair that his trainer was sitting in. “Many of the skaters had roaring headaches from the tremendous noise of the rollers as they went over the pine flooring. It sounded like the roar of escaping steam. As the skaters arrived in front of the press stand, one could not hear himself speak.” Dust flew in clouds from the passing skaters.

J. R. Meyer and M. F. Calhoun of New York City were within six miles of each other and raced hard, clocking a 4:13 mile. “Calhoun put on steam and shot ahead half a lap before Meyer knew what he was up to. He also shut off the exhaust valve and went for the man who was giving him such a shake. Slam! Bang! He went around the corners, everybody in the building expecting to see them go head over heels against the pickets that guard the track. As they went past the press stand, the draught of air caused by their rapid flight took the scorers’ sheets off the table like a flash and whisked them through the air half-way down the track.” They went two more miles like that before Meyer caught Calhoun and the two cooled off their pace.

J. R. Meyer and M. F. Calhoun of New York City were within six miles of each other and raced hard, clocking a 4:13 mile. “Calhoun put on steam and shot ahead half a lap before Meyer knew what he was up to. He also shut off the exhaust valve and went for the man who was giving him such a shake. Slam! Bang! He went around the corners, everybody in the building expecting to see them go head over heels against the pickets that guard the track. As they went past the press stand, the draught of air caused by their rapid flight took the scorers’ sheets off the table like a flash and whisked them through the air half-way down the track.” They went two more miles like that before Meyer caught Calhoun and the two cooled off their pace.

Charles O. Walton of East Boston was the favorite in the race. He had previously skated a record 243 miles in 24 hours. On this day, he reached 100 miles in less than nine hours. He cruised around the outside of the track passing others as if it was the easiest thing in the world for him to do. “Immediately after doing his 101st mile, Walton put on a spurt and made his 102nd mile in 4:18. Several of the skaters tried to keep up with his tremendous gait, but he passed them all as if they were standing still.”

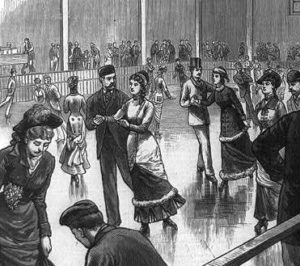

During the morning, the crowd consisted mostly of women and children because of a women/children skate being held in the center area. “It presented a moving scene of life and gayety as little girls and boys and ladies and their escorts began circling around, sometimes trying to keep up with the procession on the outside track, but very seldom succeeding.”

During the morning, the crowd consisted mostly of women and children because of a women/children skate being held in the center area. “It presented a moving scene of life and gayety as little girls and boys and ladies and their escorts began circling around, sometimes trying to keep up with the procession on the outside track, but very seldom succeeding.”

The news press liked to make fun of some of the skaters. Jno. Eichs, a German, skated leaning back at a dangerous angle, “as if he thought he was the observed of all observers.” J. Robinson of Brooklyn, New York, skated around with his mouth wide open “as if he were trying to catch all the dust in the garden.” Meyer continually chewed on a toothpick dressed in a blue suit and cap. Albert Boyst, age 19 from Port Jarvis, New Jersey, skated with his body bent over with his hands below his knees. “Then giving his body a swing, he throws his arms from one side to the other until he swings half-way across the track every time he puts one foot past the other. John Ford is a worse skater than even Frank Hart. He goes around the track as if he were on stilts and his joints composed of springs.” Some skater wore gaudy outfits. “R. I. Ward of Chicago wore a gloriously striped yellow and black sweater, a red silk neckerchief, white knee-breeches, and white belt and hat.”

News coverage was intense. The Boston Globe covered blow-by-blow details on half of their front page. During the first evening, more than 11,000 people packed the Garden to watch the racers and a polo (hocky) match on skates. They were an upscale crowd. No smoking was allowed and the bar didn’t receive much business with stacks of kegs of beer untouched. Walton reached 209 miles after 20 hours. Women stood five deep against the railing applauding the passing racers.

News coverage was intense. The Boston Globe covered blow-by-blow details on half of their front page. During the first evening, more than 11,000 people packed the Garden to watch the racers and a polo (hocky) match on skates. They were an upscale crowd. No smoking was allowed and the bar didn’t receive much business with stacks of kegs of beer untouched. Walton reached 209 miles after 20 hours. Women stood five deep against the railing applauding the passing racers.

The ultrarunner Hart still was having challenges skating. “He was crawling around the track, reminding one of a 16-year-old maiden, making her first venture as a roller skater, if by any stretch of the imagination the dark-skinned runner and his soiled corduroy suit can be thought of in the same sentence with a 16-year-old maiden in a rinking costume. Mr. Hart goes as slow as the wheels will allow him and is making a decided hit in one particular only, namely inducing the young and the foolish to back him, under the impression that he is saving himself for later.” His skating gait was so odd, that the other skaters gave him a wide berth when they came near.

The ultrarunner Hart still was having challenges skating. “He was crawling around the track, reminding one of a 16-year-old maiden, making her first venture as a roller skater, if by any stretch of the imagination the dark-skinned runner and his soiled corduroy suit can be thought of in the same sentence with a 16-year-old maiden in a rinking costume. Mr. Hart goes as slow as the wheels will allow him and is making a decided hit in one particular only, namely inducing the young and the foolish to back him, under the impression that he is saving himself for later.” His skating gait was so odd, that the other skaters gave him a wide berth when they came near.

Skaters were seen carrying coffee-pots and sucking on lemons and oranges. “Ginger ale is the favorite beverage on the track, and next to the alluring coffee pot and toothpick, the damp sponge holds sway. Johnson skated carrying a sponge in his mouth and a bottle of ginger ale in his hand. His limbs trembled like the traditional reed in the wind.”

Crashes occurred. Walton and Maddocks cut Jacob Small off, causing him to be thrown into the wicket fence surrounding the track and he broke two of the slats. Three men had to haul him off, putting him to bed for four hours. Later he was back and he collided with John Ford and crashed into the fence again, breaking four slats.

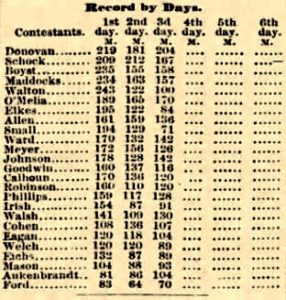

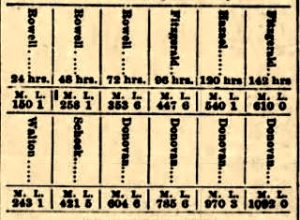

After 24 hours, Walton had reached 243 miles with an eight-mile lead, winning $100 as the Day 1 leader. Walton then left the track to sleep, soon giving up the lead to Maddocks. Three of the starters had dropped out. Ford was in last place. “His legs wobble, his mouth twitches and his shoulders work convulsively. He loses his balance for a second and then recovers himself, only to begin the same thing over again.” About 500 spectators stayed overnight watching. They were called “sleepers,” sleeping on seats all night to avoid paying admission the next day.

Day 2

During the second day, the skaters started to take extended sleeping breaks and the lead changed more often. An award of $50 was given to each man who remained on the track for at least twelve hours each day. The skaters learned the benefits of drafting behind other skaters. “It was a very pretty sight of twelve skaters, all in one line, going around at the rate of eight miles an hour, seemingly without any exertion whatever. The prince of the rink, as Meyer is called, calmly chewing a toothpick at the head of the line.”

It was discovered that the Day 2 that the leader Albert Schock of Chicago was also an ultrarunning Pedestrian. He had finished among the leaders of a 12-hour race in Chicago and competed well in a six-day foot race there. “He had a wonderful stoop and snowshoe runner-like gait.” Spectators were astonished that he was doing so well.

In the evening the big crowds returned. “The audience was such as is seen at any New York theatre. Nearly half of the 4,000 people were ladies and the brightness of their costumes and the air they gave to the occasion was such that made the place doubly attractive.”

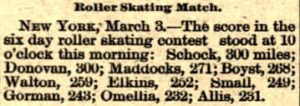

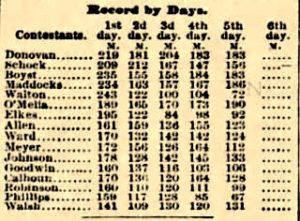

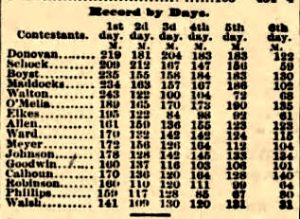

After 48 hours, Schock held the lead with 421 miles, followed by Willian Donovan, age 18, a newsboy from Elmira, New York, with 400. Donovan was doing so well that some men stepped in to be his handlers. Tom Davis became his backer and Jack Smith his trainer. Six more skaters had withdrawn included Hart with 123 miles who said that he had become tired of going around on rollers. Twenty-seven contestants remained.

Day 3

On Day 3, Donovan pulled ahead of Schock, “going around the track like mad,” but Schock continued to put up a strong fight. His trainer revealed that he was being bothered by kidney pain and had to lean forward to relieve the pain.

On Day 3, Donovan pulled ahead of Schock, “going around the track like mad,” but Schock continued to put up a strong fight. His trainer revealed that he was being bothered by kidney pain and had to lean forward to relieve the pain.

Donovan passed 600 miles at 9:55 p.m. (70 hours). A fellow Irishman spectator presented him with an enormous floral horseshoe. About 20 minutes later, Maddocks fainted and suddenly toppled to one side and fell in a heap on the track. The judges ordered that he be removed from the track and taken to a hotel. It took them ten minutes to bring him back to consciousness. A couple hours later, he returned but still struggled. He resorted to carrying a sponge saturated with ammonia which he frequently applied to his nostrils. At the end of Day 3, Donovan led with 604 miles, with Schock sixteen miles behind. Twenty-five skaters remained. Five roller hockey games kept 4,000 spectators in the arena until late at night.

Donovan passed 600 miles at 9:55 p.m. (70 hours). A fellow Irishman spectator presented him with an enormous floral horseshoe. About 20 minutes later, Maddocks fainted and suddenly toppled to one side and fell in a heap on the track. The judges ordered that he be removed from the track and taken to a hotel. It took them ten minutes to bring him back to consciousness. A couple hours later, he returned but still struggled. He resorted to carrying a sponge saturated with ammonia which he frequently applied to his nostrils. At the end of Day 3, Donovan led with 604 miles, with Schock sixteen miles behind. Twenty-five skaters remained. Five roller hockey games kept 4,000 spectators in the arena until late at night.

Day 4

Schock, the ultrarunner, started the fourth day “stiff as a poker and moving with evident pain.” He carried an old can with a spout on it and sipped from in as he rolled along. By the afternoon Donovan held a lead over him of 17 miles.

Schock, the ultrarunner, started the fourth day “stiff as a poker and moving with evident pain.” He carried an old can with a spout on it and sipped from in as he rolled along. By the afternoon Donovan held a lead over him of 17 miles.

It was cold that day in the poorly heated arena. “The air in the Garden this afternoon, despite the strong rays of the sun that shone on the pine flooring of the building through the glass overhead, was very chilly and gave the hands of the skaters a bluish look after they had been on the track for an hour or so.” The spectators put on warm overcoats and the scorers dropped their pencils often to warm their fingers.

Donovan’s lead over Schock grew to 26 miles as he found speed to go around that track very fast. At times he just tucked in behind Schock. Poor Schock could no longer straighten his body. Whenever his trainer handed him anything to eat or drink, he would support himself by putting one hand on his knee and carrying the food to his mouth with the other. Donovan gained distance when Schock was on the track and passed him repeatedly. Soon Schock had to get much needed rest at his hotel room. When he came back that evening, he was rubbed down so well with liniment that he could be smelled before he was seen.

Donovan’s lead over Schock grew to 26 miles as he found speed to go around that track very fast. At times he just tucked in behind Schock. Poor Schock could no longer straighten his body. Whenever his trainer handed him anything to eat or drink, he would support himself by putting one hand on his knee and carrying the food to his mouth with the other. Donovan gained distance when Schock was on the track and passed him repeatedly. Soon Schock had to get much needed rest at his hotel room. When he came back that evening, he was rubbed down so well with liniment that he could be smelled before he was seen.

At night, the arena was usually lit by large arch electric lights that were distributed throughout the Garden. But this night, hundreds of colored globes were lit with gas jets that crossed and recrossed the roof of the building in semi-circles. It was an amazing sight for the 1885 spectators.

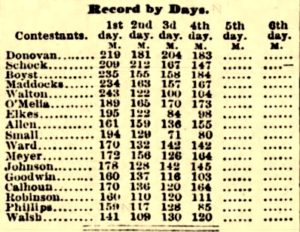

Schock’s trainers continued to work hard on him. A piece of wood 2.5 feet long, three inches wide, was used on his back and thighs to try to loosen up the muscles. “His work must be telling tremendously on him. His trainers are dousing him every five minutes with liquids of all colors and odors.” Donovan with a big lead slowed down his pace during the evening. At the end of Day 4, Donovan had 785 miles to Schock’s 755. Eight more men quit the race, leaving seventeen.

Schock’s trainers continued to work hard on him. A piece of wood 2.5 feet long, three inches wide, was used on his back and thighs to try to loosen up the muscles. “His work must be telling tremendously on him. His trainers are dousing him every five minutes with liquids of all colors and odors.” Donovan with a big lead slowed down his pace during the evening. At the end of Day 4, Donovan had 785 miles to Schock’s 755. Eight more men quit the race, leaving seventeen.

“The contest has been a surprise to athletic experts, who have hitherto claimed that no man could stand the strain of roller skates for six days, and that the Pedestrian record of Fitzgerald could not be beaten on skates.” In 1884, Patrick Fitzgerald of the U.S. had increased the six-day running record to 610 miles, also in Madison Square Garden.

“The contest has been a surprise to athletic experts, who have hitherto claimed that no man could stand the strain of roller skates for six days, and that the Pedestrian record of Fitzgerald could not be beaten on skates.” In 1884, Patrick Fitzgerald of the U.S. had increased the six-day running record to 610 miles, also in Madison Square Garden.

Day 5

In the afternoon of the fifth day, Donovan had built up a commanding lead of 41 miles. Boyat caught up and passed the struggling Schock into second place during the evening, despite rolling at a walking pace. The excitement of the race was dwindling. The audience paid more attention to the carnival than to the racers.

In the afternoon of the fifth day, Donovan had built up a commanding lead of 41 miles. Boyat caught up and passed the struggling Schock into second place during the evening, despite rolling at a walking pace. The excitement of the race was dwindling. The audience paid more attention to the carnival than to the racers.

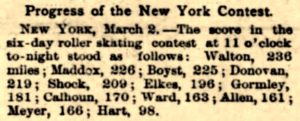

The long miles were taking a toll on the athletes. “Donovan, it was rumored in the Garden, was getting light in his head and had proved intractable to his trainers. They wanted him to ease up and not do so much hard work, fearing that he would break down from the strain, for he was going some miles at the rate of twelve miles an hour, altogether too fast for a man to go who was fifty-four miles in the lead of the second man.” Donovan continued to think he would be caught, and his trainers tried everything, including threats to get that idea out of this head. But Donovan just did not understand and charged ahead. At the end of Day 5, Donovan had 970 miles to Boyat’s 915. Sixteen skaters remained.

The long miles were taking a toll on the athletes. “Donovan, it was rumored in the Garden, was getting light in his head and had proved intractable to his trainers. They wanted him to ease up and not do so much hard work, fearing that he would break down from the strain, for he was going some miles at the rate of twelve miles an hour, altogether too fast for a man to go who was fifty-four miles in the lead of the second man.” Donovan continued to think he would be caught, and his trainers tried everything, including threats to get that idea out of this head. But Donovan just did not understand and charged ahead. At the end of Day 5, Donovan had 970 miles to Boyat’s 915. Sixteen skaters remained.

Day 6

As the last day began at midnight, John O’Melia, age 19 of Boston, had vowed that he would pass Eugene Maddocks to claim third place. During the night he succeeded. His trainers rigged up a bed on the south side of the track where they put him to rest after he made the pass. The boy was so tired that he was sound asleep in seconds. Only three men were on the track at 2 a.m.

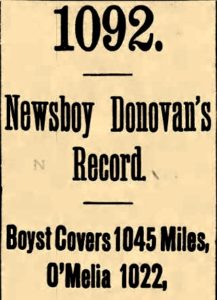

At 5:24 a.m., Donovan passed 1,000 miles. “The few people who were then awake cheered heartily as the scorer bulletined the figures, and their cheers awoke the slumbering regulars on the top rows of benches in the galleries, and they too cheered the shock-headed pallid-faced youth from Elmira, New York.”

During the morning, snow fell outside. “It made the Garden chilly and uncomfortable, the heaters in the building being inadequate to keep the place warm. Many of the chronic spectator sleepers in the place were rudely disturbed by a gang of boys who went around the Garden with a rope, which they tied to the sleeping men’s chairs and pulled them from under, letting the unconscious occupants fall down and waking them up so quickly that they were bewildered for several minutes.”

The second-place skater, Boyst, reached 1,000 miles at 11:56 a.m., with about twelve hours to go. “Schock wore a new velvet suit this morning but went very slowly.” The building started to fill up at 2 p.m. with ten hours to go with admission tickets of 50 cents. People stood outside the picket fence standing four deep. As some of the skaters realized that they could not catch the next person ahead in the standings, they quit skating. Maddocks pled with his trainer who was running along with him to allow him to go off the track. “If you don’t let me go off, I’ll have to drop on the track. I can’t stand it any longer.”

Ultrarunner, Schock, continued on and along the way received a wreath and anchor floral arrangement from fans. “The trainers’ tables looked like conservatories, banked high with almost every product of flora.”

With the end coming, the band started playing at 8 p.m. which infused new life into the men on the track. As Donavan skated, admirers would lean over the railing and give him money. But Donovan also quit several hours early which disappointed people wagering that he would reach 1,100 miles. Finally, only Goodwin was on the track, because all the others had quit. He wanted to quit too, so the end came officially early at 10:15 p.m.

With the end coming, the band started playing at 8 p.m. which infused new life into the men on the track. As Donavan skated, admirers would lean over the railing and give him money. But Donovan also quit several hours early which disappointed people wagering that he would reach 1,100 miles. Finally, only Goodwin was on the track, because all the others had quit. He wanted to quit too, so the end came officially early at 10:15 p.m.

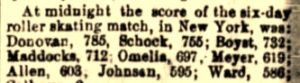

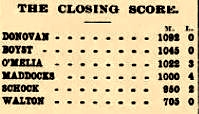

Donovan won by 47 miles, with 1,092. “After the race was over, the referee presented the men with medals and money, while the crowd stood around and clapped and cheered the men who were presented with prizes.” The band played “Home Sweet Home” and the crowd left the building as Barnum’s circus men came in to tear up the track and transform the building into a circus. Donovan’s ecstatic trainers, Tom Davis and Jack Smith took Donovan to Putnum house and fed him oatmeal gruel, two soft-boiled eggs, toast, and tea. A doctor examined him and said the boy had worn himself out and needed a week’s rest.

Donovan won by 47 miles, with 1,092. “After the race was over, the referee presented the men with medals and money, while the crowd stood around and clapped and cheered the men who were presented with prizes.” The band played “Home Sweet Home” and the crowd left the building as Barnum’s circus men came in to tear up the track and transform the building into a circus. Donovan’s ecstatic trainers, Tom Davis and Jack Smith took Donovan to Putnum house and fed him oatmeal gruel, two soft-boiled eggs, toast, and tea. A doctor examined him and said the boy had worn himself out and needed a week’s rest.

The event was viewed to be a great success. “No one supposed a week earlier that four men would have 1,000 miles to their credit. This remarkable performance is now a matter of record. The only previous records for six-day contests are in go-as-you-please races.” The newspapers compared the miles achieved each day for the best Pedestrians compared to that achieved by the skaters.

Aftermath

Donovan’s condition was very concerning. “He is completely broken up physically and has been out of bed only for an hour since the contest ended. His feet were in such a condition when he left the track that his stockings could not be removed. The sight of his right foot and leg made the trainer sick. A hole has been worn in the hollow of the foot and it has festered and inflamed. The sore extended away up the leg to the knee. So deep was the furrow that one could almost see the shinbone through it.” The doctors feared that to coloring in his socked could have poisoned his system. He remained deadly pale.

Donovan’s condition was very concerning. “He is completely broken up physically and has been out of bed only for an hour since the contest ended. His feet were in such a condition when he left the track that his stockings could not be removed. The sight of his right foot and leg made the trainer sick. A hole has been worn in the hollow of the foot and it has festered and inflamed. The sore extended away up the leg to the knee. So deep was the furrow that one could almost see the shinbone through it.” The doctors feared that to coloring in his socked could have poisoned his system. He remained deadly pale.

The following day, reporters visited Donovan at his hotel room. “His feet are in a terrible condition, and his performance is to be greatly wondered at when a view of him is obtained. His complexion is ghastly, and his eyes are sunk deep in their sockets. He has a running sore on his right leg below the knee and his sufferings during the last hours of the race must have been very great. His father and some friends from Elmira were with him during the day.” It was remarkable that a week earlier he was unknown and penniless.

On the second day after the finish, Donovan was not doing well. “There were rumors at one time that he was dying, and the lad certainly did himself an irreparable injury by continuing in the race without proper attendance. It is the wonder of the physicians who had been called in since his retirement from the track that he could have finished as he did.”

But soon he appeared to recover. “Today he is a champion, well-dress, well-fed, with every comfort at his command and richer than he ever was.” A skating manufacturing company sent Donovan a pair of gold mounted roller skates.

Skaters Head Home

Other participants were leaving with much less than Donovan. Maddocks came in 4th place. After expenses were paid, he had only $4 left over. The others “wandered about the city complaining with vigor and much profanity of the way in which they had been left out in the cold and had not been fairly treated by management.” The skaters had been given room and board and a week’s salary, but they demanded more. “There was a stormy scene at the managers’ offices, with much hot talk. Some of the would-be champions were bought off with a $10 bill and sent away rejoicing.”

The New York theaters went on a crusade against roller skating because of the business that the event took away from them. They denied that was their motivation. “It is the degrading influence that all such crazes have upon the show business in general. A great percentage of them are going to their ruin. The moral side of the matter is still more awful to contemplate.”

The New York theaters went on a crusade against roller skating because of the business that the event took away from them. They denied that was their motivation. “It is the degrading influence that all such crazes have upon the show business in general. A great percentage of them are going to their ruin. The moral side of the matter is still more awful to contemplate.”

The greatest ultrarunners of the time, Charles Rowell and George Littlewood were cabled and encouraged to learn roller skating to compete in a future six-day race. Frank Hart was practicing every day and getting better. Other ultrarunners, including George Hazel, started to also put on the skates and very quickly became experts. A week after the race, Donovan signed intent documents for a six-day challenge race against Kenneth A. Skinner for $1,000.

Donovan’s hometown of Elmira was howling for their hero to return. The boy’s father was determined to take him home and did so against the protests of his trainers. Three days after the race he was taken by train to Elmira by his relatives. “Donovan was met at the Elmira depot by half the town, and the same evening, a big reception was given to him at the rink. He was the hero of the hour and exhibited at nearby towns.”

Tragedies

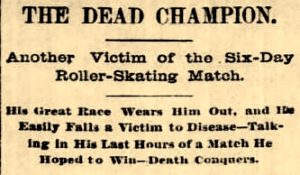

Joseph Cohen, one of the older contestants in the race at age 26, was a dry goods clerk from Brooklyn, New York. He had reached at least 350 miles but quit on the 4th day. He went home very discouraged and weary that he did not receive a promised $50. “His condition grew rapidly worse, and before a physician could be summoned, he expired. He leaves a wife and two children in almost destitute circumstances. His friends all declared that while not exactly a strong man, his health had been good previous to the roller-skating race.”

Cohen died on March 17, 1885, ten days after the race. It was said that he died “from inflammation of the brain, cold and exhaustion.” Spinal meningitis was mentioned as a pre-existing condition. A Brooklyn jury of inquest on his death recommended that a law be passed to prohibit such events in the future that exceeded four hours.

Cohen died on March 17, 1885, ten days after the race. It was said that he died “from inflammation of the brain, cold and exhaustion.” Spinal meningitis was mentioned as a pre-existing condition. A Brooklyn jury of inquest on his death recommended that a law be passed to prohibit such events in the future that exceeded four hours.

Donovan’s trainers went to Elmira to start getting him ready for the next big event. They found him with a severe cold, coughing. They believed that the family was killing the boy with all the appearances at skating rink halls. Donovan wanted to return to New York with his trainers to recover and prepare for his next race. They left for New York after a week.

At New York, again in Putnam House, it was soon discovered that he had pneumonia in his left lung. “He was fast recovering when, by imprudent exposure at an open window, he contracted a fresh cold, which resulted in a severe and continual attack of cramps in the stomach.” The doctor was summoned and he diagnosed a serious heart issue.

Donovan suffered for a couple more days and was visited by his trainer, Jack Smith. “Donovan put his arm around his neck and said: ‘I wish I had something to give you Jack, you’ve been so kind to me.’ His blue eyes were fixed on Smith’s face and tried to speak again, but sat back on the pillow. Smith thought he was asleep or had swooned, but in a moment discovered that his heart had ceased to beat.”

Donovan suffered for a couple more days and was visited by his trainer, Jack Smith. “Donovan put his arm around his neck and said: ‘I wish I had something to give you Jack, you’ve been so kind to me.’ His blue eyes were fixed on Smith’s face and tried to speak again, but sat back on the pillow. Smith thought he was asleep or had swooned, but in a moment discovered that his heart had ceased to beat.”

Donovon died on April 5, 1885, just about a month after his victory. “Dr. Wood said the race had left the boy’s heart in a very weak condition and made him very susceptible to cold. The cause of death was exposure after recovering from his illness, and the pneumonia, which exhausted the skater’s system, was contracted by his being outdoors so soon after his exertions in the race.”

Protests Against Six-day Races

News of his death spread across the country. Immediately, efforts were made to prohibit six-day races which was characterized as including brutality, betting, gambling, abuses and horrors. “The deaths of Donovan and Cohen demonstrates the necessity of the passage of a law to prevent such contests.” In St. Louis it was written, “There is absolutely nothing to commend these exhibitions while a great deal can be advanced against them. The fate of poor Willy Donovan, the victor is too fresh in our minds to permit us to advocate the repetition of such a race, and we trust the National Rink Association will take the matter in hand.”

News of his death spread across the country. Immediately, efforts were made to prohibit six-day races which was characterized as including brutality, betting, gambling, abuses and horrors. “The deaths of Donovan and Cohen demonstrates the necessity of the passage of a law to prevent such contests.” In St. Louis it was written, “There is absolutely nothing to commend these exhibitions while a great deal can be advanced against them. The fate of poor Willy Donovan, the victor is too fresh in our minds to permit us to advocate the repetition of such a race, and we trust the National Rink Association will take the matter in hand.”

The topic was highly debated. A counter argument was, “This proposed skatorial enactment would most certainly not be necessary to prevent foolish young fellows like Donovan and Cohen from committing slow suicide in public, were it not that great crowds of people, and many of them leading citizens are willing to pay to see them do it.”

The Chicago Tribune wrote, “No one knows the condition of the survivors of that miserable race. Some of them may be none the worse for brain excitement and physical and nervous exhaustion of the week’s folly. But it is safe to accept the fate of the winner and the loser as a warning to ambitious youths to seek glory and fortune in some more rational and less dangerous competition. The man who can carry 1,092 bricks up a lader at a moderate rate has a better chance for long life and fortune than the infatuated youth who wants to skate 1,092 miles in 144 hours.”

Even so, despite public protests, another six-day race was held in Madison Square Garden in May 1885, including ultrarunning greats, Albert Schock and Charles Harriman. Alexander Snowden, age 22 of Canada, won with are new record, 1,163 miles. Harriman reached 890 miles. The event was a financial failure as the managers lost heavy amounts of money. Other six-day races were held in 1886 that limited the number of hours that could be skated each day. They were also financial failures.

Even so, despite public protests, another six-day race was held in Madison Square Garden in May 1885, including ultrarunning greats, Albert Schock and Charles Harriman. Alexander Snowden, age 22 of Canada, won with are new record, 1,163 miles. Harriman reached 890 miles. The event was a financial failure as the managers lost heavy amounts of money. Other six-day races were held in 1886 that limited the number of hours that could be skated each day. They were also financial failures.

In 1906 some six-day roller skating races reappeared, with 12-hours per day limitations. Some people wondered if a “Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Athletes” was needed. In 1929, true six-day races returned but they involved three-man relays, included some ultrarunners and was broadcast over the radio.

In 1906 some six-day roller skating races reappeared, with 12-hours per day limitations. Some people wondered if a “Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Athletes” was needed. In 1929, true six-day races returned but they involved three-man relays, included some ultrarunners and was broadcast over the radio.

Sources:

- Janesville Daily Gazette (Wisconsin), Dec 14, 1867

- Cincinnati Enquirer (Ohio), Mar 24, 1868

- Daily Missouri Republican (St. Louis, Missouri), Apr 5, 1868

- The Post-Star (Glens Falls, New York), Aug 12, 1884

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Oct 26, 1883, Mar 1-10, 15, 17, Apr 10, 13, 16, May 8, 1885

- The Muscatine Journal (Iowa), Feb 6, 1885

- The Inter Ocean (Chicago, Illinois), Feb 26, 1885

- The Fall River Daily Herald (Massachusetts), Mar 2, 1885

- The Topeka State Journal (Kansas), Mar 2, 1885

- The Illustrated Police News (London, England), Nov 30, 1878

- Sunday Truth (Buffalo, New York), Feb 8, 1885

- The Critic (Washington, D.C.), Feb 26, 1885

- Times Union (Brooklyn, New York), Mar 2, 1885

- The New York Times (New York), Mar 2, 1885

- St Louis Post-Dispatch (Missouri), Apr 30, 1885

- The Wichita Beacon (Kansas), May 7, 1885

- Lebanon Daily News (Pennsylvania), Mar 10, 1885

- The Choctaw Herold (Butler, Alabama), Apr 2, 1885

- Buffalo Evening News (New York), Apr 15, 1885

- The Potter Enterprise (Coudersport, Pennsylvania), Jun 17, 1885