Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 30:47 — 37.0MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

You can read, listen, or watch

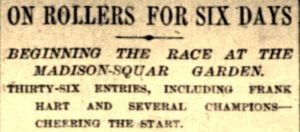

While not technically ultrarunning, the emerging six-day roller skate races mirrored significantly the six-day foot races that had become the most popular spectator sport for several years in the United States. Why not put wheels on those ultrarunning feet and see what could be done? The results were fascinating, and in 1885 the Boston Globe left behind very detailed play-by-play results that revealed what these unique races were like. How many miles could an extreme endurance athlete skate in six days on primitive rolling skates?

| The Ultrarunning History Podcast is included in the People Choice podcast awards in the history category. Please help me by voting for the Ultrarunning History Podcast. During July 2021, go to https://podcastawards.com to register and nominate “Ultrarunning History” in the “History” category. Thanks! |

Early Roller Skating

Roller skating was thought to be invented as early as 1735 by John Joseph Merlin of Belgium. It was said that while showing off his new wheeled shoes at a party in London, that he crashed into a mirror. In the early 1800s roller skates were introduced in isolated cases into the theater as an alternative to ice skating performances. In 1854 a French company performed “La Prophet” in New Orleans, Louisiana, and the entire ballet of one hundred performers appeared on roller skates.

In 1863, the four-wheeled roller skate, or quad skate, was invented by James Leonard Plimpton making it possible for amateurs to participate. The first public roller rink was opened in 1866 by Plimpton in New York City, who also introduced a roller skating academy. At first, he did not mass-market his patented skate and would only let them be used in rinks with maple floors.

The Six-Day Race

The first known six-day skating match was held from May 5-10, 1879, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, between three skaters, won by Mayer with 685 miles.

Long Distance Roller Skating

1885 Six-Day Race at Madison Square Garden

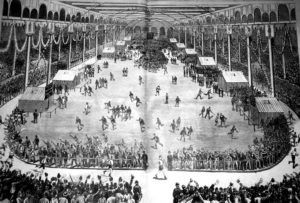

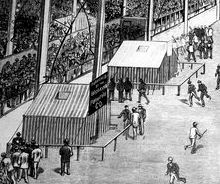

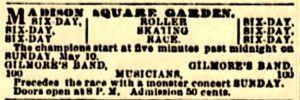

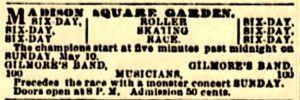

Excitement increased as the event approached. The Boston Globe reported, “The arrangements for the great international six-day race carnival and tournament on roller skates at Madison Square Garden are completed and will constitute the greatest enterprise of its kind ever attempted in the annals of amusement. The entire surface of the Garden has been transformed into the largest rink in the world, with an excellent skating surface, skate rooms and appropriate offices erected and provided with a track twenty feet wide. It is believed that at least ten men will cover 1,000 miles in six days.”

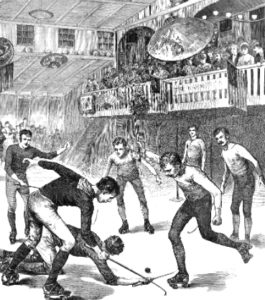

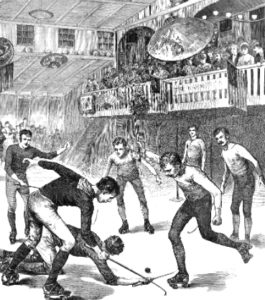

Many entertaining side-shows were planned to be held during the race including, backward racing, sack races, orange races, acrobatic skating, dancing on skates, stilt skating, Roman games on rollers, rope skipping on skates, polo on skates, bean races, egg races and potato races.

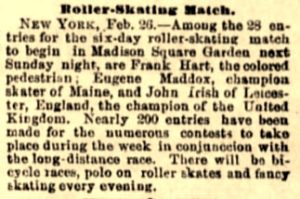

Entrants

William Donovan

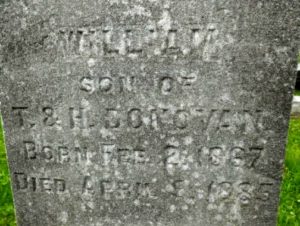

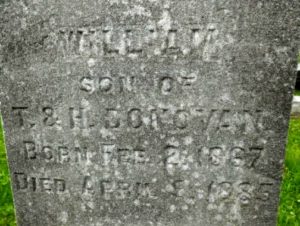

Willian Donovan, age 18, was from Elmira New York, a son of Irish immigrants. He was a newsboy and a shoemaker by trade. As roller skating started to become popular, he entered and won several short-distance matches and tried to turn professional. He heard about the six-day race and a few of his chums urged him to enter. He had no funds but said he would do it if he could come up with a skating outfit. One of his friends purchased a shirt for him and loaned him a silk handkerchief. Others gave shoes, caps, a belt, overcoat, and knee breeches. Seven dollars was raised for him to get him to New York. “Young Donovan on reaching New York was alone and friendless.”

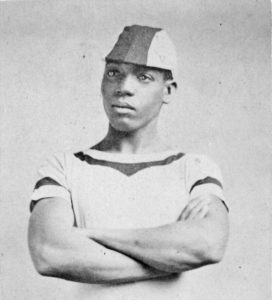

Frank Hart

Albert Schock

Albert Schock (1857-1921), age 28, was from Chicago, Illinois. He was 140 pounds and stood five feet, seven inches tall. He was an experienced ultrarunning pedestrian, a veteran of three six-day go-as-you-please running races in Chicago. He had performed well, finishing in second, third, and fifth place.

The Start

Gilmore’s Band played on a bandstand in the center of the floor. “Just as the band struck up the first melodious blast, the gentleman of the bass tuba fell through and was lost to sight.” The band did not miss a beat, finished the number and then moved to a safer place at the south side of the Garden.

Early injuries occurred. Jno. Goodwin, experienced a bad fall injuring his knee and hip when he tried to stop himself in front of a chair that his trainer was sitting in. “Many of the skaters had roaring headaches from the tremendous noise of the rollers as they went over the pine flooring. It sounded like the roar of escaping steam. As the skaters arrived in front of the press stand, one could not hear himself speak.” Dust flew in clouds from the passing skaters.

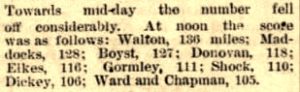

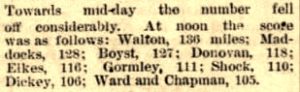

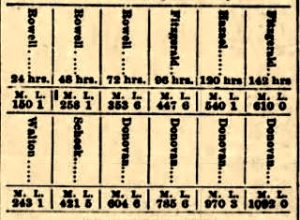

Charles O. Walton of East Boston was the favorite in the race. He had previously skated a record 243 miles in 24 hours. On this day, he reached 100 miles in less than nine hours. He cruised around the outside of the track passing others as if it was the easiest thing in the world for him to do. “Immediately after doing his 101st mile, Walton put on a spurt and made his 102nd mile in 4:18. Several of the skaters tried to keep up with his tremendous gait, but he passed them all as if they were standing still.”

The news press liked to make fun of some of the skaters. Jno. Eichs, a German, skated leaning back at a dangerous angle, “as if he thought he was the observed of all observers.” J. Robinson of Brooklyn, New York, skated around with his mouth wide open “as if he were trying to catch all the dust in the garden.” Meyer continually chewed on a toothpick dressed in a blue suit and cap. Albert Boyst, age 19 from Port Jarvis, New Jersey, skated with his body bent over with his hands below his knees. “Then giving his body a swing, he throws his arms from one side to the other until he swings half-way across the track every time he puts one foot past the other. John Ford is a worse skater than even Frank Hart. He goes around the track as if he were on stilts and his joints composed of springs.” Some skater wore gaudy outfits. “R. I. Ward of Chicago wore a gloriously striped yellow and black sweater, a red silk neckerchief, white knee-breeches, and white belt and hat.”

Skaters were seen carrying coffee-pots and sucking on lemons and oranges. “Ginger ale is the favorite beverage on the track, and next to the alluring coffee pot and toothpick, the damp sponge holds sway. Johnson skated carrying a sponge in his mouth and a bottle of ginger ale in his hand. His limbs trembled like the traditional reed in the wind.”

Crashes occurred. Walton and Maddocks cut Jacob Small off, causing him to be thrown into the wicket fence surrounding the track and he broke two of the slats. Three men had to haul him off, putting him to bed for four hours. Later he was back and he collided with John Ford and crashed into the fence again, breaking four slats.

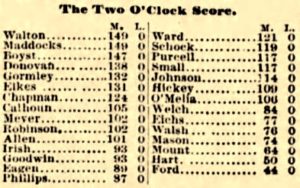

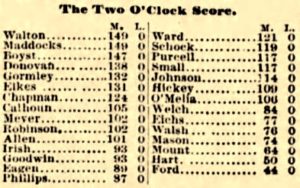

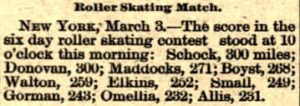

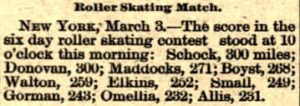

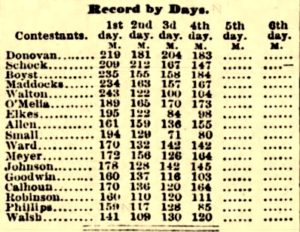

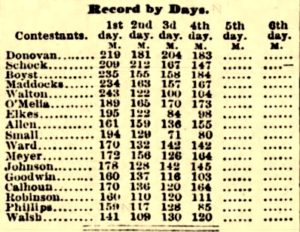

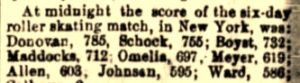

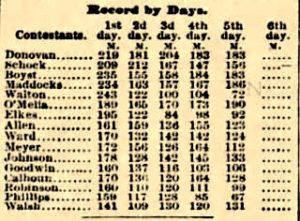

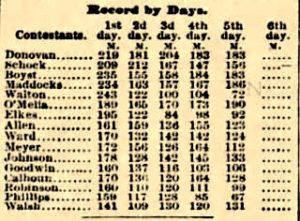

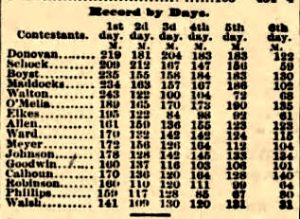

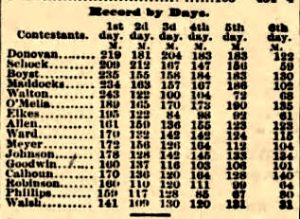

After 24 hours, Walton had reached 243 miles with an eight-mile lead, winning $100 as the Day 1 leader. Walton then left the track to sleep, soon giving up the lead to Maddocks. Three of the starters had dropped out. Ford was in last place. “His legs wobble, his mouth twitches and his shoulders work convulsively. He loses his balance for a second and then recovers himself, only to begin the same thing over again.” About 500 spectators stayed overnight watching. They were called “sleepers,” sleeping on seats all night to avoid paying admission the next day.

Day 2

During the second day, the skaters started to take extended sleeping breaks and the lead changed more often. An award of $50 was given to each man who remained on the track for at least twelve hours each day. The skaters learned the benefits of drafting behind other skaters. “It was a very pretty sight of twelve skaters, all in one line, going around at the rate of eight miles an hour, seemingly without any exertion whatever. The prince of the rink, as Meyer is called, calmly chewing a toothpick at the head of the line.”

It was discovered that the Day 2 that the leader Albert Schock of Chicago was also an ultrarunning Pedestrian. He had finished among the leaders of a 12-hour race in Chicago and competed well in a six-day foot race there. “He had a wonderful stoop and snowshoe runner-like gait.” Spectators were astonished that he was doing so well.

In the evening the big crowds returned. “The audience was such as is seen at any New York theatre. Nearly half of the 4,000 people were ladies and the brightness of their costumes and the air they gave to the occasion was such that made the place doubly attractive.”

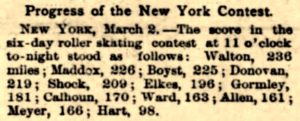

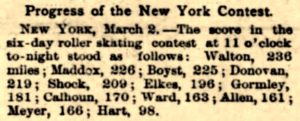

After 48 hours, Schock held the lead with 421 miles, followed by Willian Donovan, age 18, a newsboy from Elmira, New York, with 400. Donovan was doing so well that some men stepped in to be his handlers. Tom Davis became his backer and Jack Smith his trainer. Six more skaters had withdrawn included Hart with 123 miles who said that he had become tired of going around on rollers. Twenty-seven contestants remained.

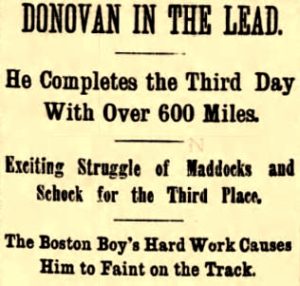

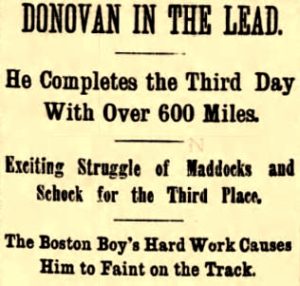

Day 3

Day 4

It was cold that day in the poorly heated arena. “The air in the Garden this afternoon, despite the strong rays of the sun that shone on the pine flooring of the building through the glass overhead, was very chilly and gave the hands of the skaters a bluish look after they had been on the track for an hour or so.” The spectators put on warm overcoats and the scorers dropped their pencils often to warm their fingers.

At night, the arena was usually lit by large arch electric lights that were distributed throughout the Garden. But this night, hundreds of colored globes were lit with gas jets that crossed and recrossed the roof of the building in semi-circles. It was an amazing sight for the 1885 spectators.

Day 5

Day 6

As the last day began at midnight, John O’Melia, age 19 of Boston, had vowed that he would pass Eugene Maddocks to claim third place. During the night he succeeded. His trainers rigged up a bed on the south side of the track where they put him to rest after he made the pass. The boy was so tired that he was sound asleep in seconds. Only three men were on the track at 2 a.m.

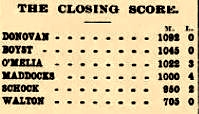

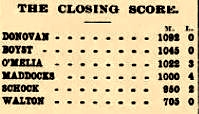

At 5:24 a.m., Donovan passed 1,000 miles. “The few people who were then awake cheered heartily as the scorer bulletined the figures, and their cheers awoke the slumbering regulars on the top rows of benches in the galleries, and they too cheered the shock-headed pallid-faced youth from Elmira, New York.”

During the morning, snow fell outside. “It made the Garden chilly and uncomfortable, the heaters in the building being inadequate to keep the place warm. Many of the chronic spectator sleepers in the place were rudely disturbed by a gang of boys who went around the Garden with a rope, which they tied to the sleeping men’s chairs and pulled them from under, letting the unconscious occupants fall down and waking them up so quickly that they were bewildered for several minutes.”

The second-place skater, Boyst, reached 1,000 miles at 11:56 a.m., with about twelve hours to go. “Schock wore a new velvet suit this morning but went very slowly.” The building started to fill up at 2 p.m. with ten hours to go with admission tickets of 50 cents. People stood outside the picket fence standing four deep. As some of the skaters realized that they could not catch the next person ahead in the standings, they quit skating. Maddocks pled with his trainer who was running along with him to allow him to go off the track. “If you don’t let me go off, I’ll have to drop on the track. I can’t stand it any longer.”

Ultrarunner, Schock, continued on and along the way received a wreath and anchor floral arrangement from fans. “The trainers’ tables looked like conservatories, banked high with almost every product of flora.”

The event was viewed to be a great success. “No one supposed a week earlier that four men would have 1,000 miles to their credit. This remarkable performance is now a matter of record. The only previous records for six-day contests are in go-as-you-please races.” The newspapers compared the miles achieved each day for the best Pedestrians compared to that achieved by the skaters.

Aftermath

The following day, reporters visited Donovan at his hotel room. “His feet are in a terrible condition, and his performance is to be greatly wondered at when a view of him is obtained. His complexion is ghastly, and his eyes are sunk deep in their sockets. He has a running sore on his right leg below the knee and his sufferings during the last hours of the race must have been very great. His father and some friends from Elmira were with him during the day.” It was remarkable that a week earlier he was unknown and penniless.

On the second day after the finish, Donovan was not doing well. “There were rumors at one time that he was dying, and the lad certainly did himself an irreparable injury by continuing in the race without proper attendance. It is the wonder of the physicians who had been called in since his retirement from the track that he could have finished as he did.”

But soon he appeared to recover. “Today he is a champion, well-dress, well-fed, with every comfort at his command and richer than he ever was.” A skating manufacturing company sent Donovan a pair of gold mounted roller skates.

Skaters Head Home

Other participants were leaving with much less than Donovan. Maddocks came in 4th place. After expenses were paid, he had only $4 left over. The others “wandered about the city complaining with vigor and much profanity of the way in which they had been left out in the cold and had not been fairly treated by management.” The skaters had been given room and board and a week’s salary, but they demanded more. “There was a stormy scene at the managers’ offices, with much hot talk. Some of the would-be champions were bought off with a $10 bill and sent away rejoicing.”

The greatest ultrarunners of the time, Charles Rowell and George Littlewood were cabled and encouraged to learn roller skating to compete in a future six-day race. Frank Hart was practicing every day and getting better. Other ultrarunners, including George Hazel, started to also put on the skates and very quickly became experts. A week after the race, Donovan signed intent documents for a six-day challenge race against Kenneth A. Skinner for $1,000.

Donovan’s hometown of Elmira was howling for their hero to return. The boy’s father was determined to take him home and did so against the protests of his trainers. Three days after the race he was taken by train to Elmira by his relatives. “Donovan was met at the Elmira depot by half the town, and the same evening, a big reception was given to him at the rink. He was the hero of the hour and exhibited at nearby towns.”

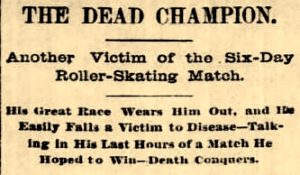

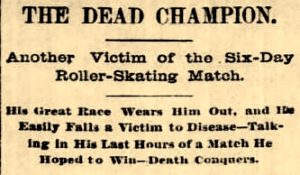

Tragedies

Joseph Cohen, one of the older contestants in the race at age 26, was a dry goods clerk from Brooklyn, New York. He had reached at least 350 miles but quit on the 4th day. He went home very discouraged and weary that he did not receive a promised $50. “His condition grew rapidly worse, and before a physician could be summoned, he expired. He leaves a wife and two children in almost destitute circumstances. His friends all declared that while not exactly a strong man, his health had been good previous to the roller-skating race.”

Donovan’s trainers went to Elmira to start getting him ready for the next big event. They found him with a severe cold, coughing. They believed that the family was killing the boy with all the appearances at skating rink halls. Donovan wanted to return to New York with his trainers to recover and prepare for his next race. They left for New York after a week.

At New York, again in Putnam House, it was soon discovered that he had pneumonia in his left lung. “He was fast recovering when, by imprudent exposure at an open window, he contracted a fresh cold, which resulted in a severe and continual attack of cramps in the stomach.” The doctor was summoned and he diagnosed a serious heart issue.

Donovon died on April 5, 1885, just about a month after his victory. “Dr. Wood said the race had left the boy’s heart in a very weak condition and made him very susceptible to cold. The cause of death was exposure after recovering from his illness, and the pneumonia, which exhausted the skater’s system, was contracted by his being outdoors so soon after his exertions in the race.”

Protests Against Six-day Races

The topic was highly debated. A counter argument was, “This proposed skatorial enactment would most certainly not be necessary to prevent foolish young fellows like Donovan and Cohen from committing slow suicide in public, were it not that great crowds of people, and many of them leading citizens are willing to pay to see them do it.”

The Chicago Tribune wrote, “No one knows the condition of the survivors of that miserable race. Some of them may be none the worse for brain excitement and physical and nervous exhaustion of the week’s folly. But it is safe to accept the fate of the winner and the loser as a warning to ambitious youths to seek glory and fortune in some more rational and less dangerous competition. The man who can carry 1,092 bricks up a lader at a moderate rate has a better chance for long life and fortune than the infatuated youth who wants to skate 1,092 miles in 144 hours.”

Sources:

- Janesville Daily Gazette (Wisconsin), Dec 14, 1867

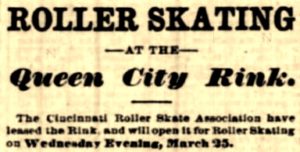

- Cincinnati Enquirer (Ohio), Mar 24, 1868

- Daily Missouri Republican (St. Louis, Missouri), Apr 5, 1868

- The Post-Star (Glens Falls, New York), Aug 12, 1884

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Oct 26, 1883, Mar 1-10, 15, 17, Apr 10, 13, 16, May 8, 1885

- The Muscatine Journal (Iowa), Feb 6, 1885

- The Inter Ocean (Chicago, Illinois), Feb 26, 1885

- The Fall River Daily Herald (Massachusetts), Mar 2, 1885

- The Topeka State Journal (Kansas), Mar 2, 1885

- The Illustrated Police News (London, England), Nov 30, 1878

- Sunday Truth (Buffalo, New York), Feb 8, 1885

- The Critic (Washington, D.C.), Feb 26, 1885

- Times Union (Brooklyn, New York), Mar 2, 1885

- The New York Times (New York), Mar 2, 1885

- St Louis Post-Dispatch (Missouri), Apr 30, 1885

- The Wichita Beacon (Kansas), May 7, 1885

- Lebanon Daily News (Pennsylvania), Mar 10, 1885

- The Choctaw Herold (Butler, Alabama), Apr 2, 1885

- Buffalo Evening News (New York), Apr 15, 1885

- The Potter Enterprise (Coudersport, Pennsylvania), Jun 17, 1885