Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 26:30 — 31.6MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

You can read, listen, or watch

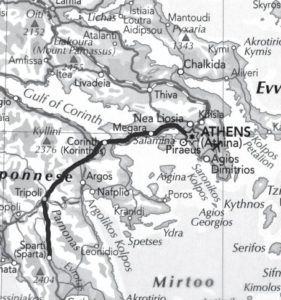

Spartathlon is one of the most prestigious ultramarathons in the world. It is a race of about 246 km (153 miles), that takes place each September in Greece, running from Athens to Sparta on a highly significant route in world history. It attracts many of the greatest ultrarunners in the world.

This is part one of a series on the history of Spartathlon. In this episode, we will cover how Spartathlon was born, a story that has never been fully told until now. It was the brainchild of an officer in the Royal Air Force, John Foden.

Pheidippides’ Historic Run

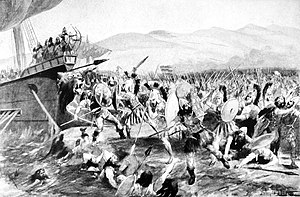

In 490 B.C., one of the most famous battles in world history was held between the Athenians and the Persians who invaded what we now call Greece, landing at Marathon. Before that battle, a professional messenger named Pheidippides was sent by Athenian generals to Sparta, with an urgent message to ask for reinforcements against the much larger Persian incursion.

Pheidippides ran an estimated 250 kms (155 miles) and arrived at Sparta on the next day, likely about 36 hours, and then returned walking. There are many versions of this story. Some say his run was before the battle and others say after. One Romon version, more than a centry later, states that he ran back and he died on returning.

Pheidippides ran an estimated 250 kms (155 miles) and arrived at Sparta on the next day, likely about 36 hours, and then returned walking. There are many versions of this story. Some say his run was before the battle and others say after. One Romon version, more than a centry later, states that he ran back and he died on returning.

But the important thing about the story for ultrarunning, is that Pheidippides made an ultra-distance run of about 155 miles in less than two days. If it were from dawn to dusk of the second day, that would have been 36 hours. The Spartan reinforcements did not immediately leave to help because of a festival and arrived too late for the Battle of Marathon, but the Athenians had triumphed over the more numerous Persians. People have wondered for years if the tale of Pheidippides could be true, running that difficult long distance across the rugged land in less than two days.

But the important thing about the story for ultrarunning, is that Pheidippides made an ultra-distance run of about 155 miles in less than two days. If it were from dawn to dusk of the second day, that would have been 36 hours. The Spartan reinforcements did not immediately leave to help because of a festival and arrived too late for the Battle of Marathon, but the Athenians had triumphed over the more numerous Persians. People have wondered for years if the tale of Pheidippides could be true, running that difficult long distance across the rugged land in less than two days.

John Foden

John Boyd Foden (1926-2016) was born on May 7, 1926, in Winchester, Australia. His parents, also Australian, were James Clement Foden (1894-1978) and Rosalind Ida Boyd (1888-1957) of Scottish ancestry. The Fodens had lived in Australia for generations. John’s father, James, was an aviator who learned to fly a biplane in Hendon, England, in 1917.

John Boyd Foden (1926-2016) was born on May 7, 1926, in Winchester, Australia. His parents, also Australian, were James Clement Foden (1894-1978) and Rosalind Ida Boyd (1888-1957) of Scottish ancestry. The Fodens had lived in Australia for generations. John’s father, James, was an aviator who learned to fly a biplane in Hendon, England, in 1917.

James served during World War I in the Royal Flying Corps and was awarded the Air Force Cross. In 1924 he was promoted to a Flight Lieutenant. He made his career in the Royal Air Force and he retired a Group Captain. His love for aviation and the Royal Air Force was passed down to his son John.

James served during World War I in the Royal Flying Corps and was awarded the Air Force Cross. In 1924 he was promoted to a Flight Lieutenant. He made his career in the Royal Air Force and he retired a Group Captain. His love for aviation and the Royal Air Force was passed down to his son John.

Over the years, the Foden family would make multiple long sea voyages to Great Britain to visit family in England and Scotland. At the age of seven, John travelled to and from England by steam ship with his mother, his three-year-old sister, Pauline Margaret Foden, and his uncle, James Shields Boyd.

Foden served in World War II as a paratrooper for Australia and after the war went to England. In 1948, at the age of 22, he married Vera Joan Colyer (1926-2001) of England. He later became a career officer in the Royal Air Force (RAF). In 1952, they had a son, David Michael Foden.

Foden served in World War II as a paratrooper for Australia and after the war went to England. In 1948, at the age of 22, he married Vera Joan Colyer (1926-2001) of England. He later became a career officer in the Royal Air Force (RAF). In 1952, they had a son, David Michael Foden.

Foden Takes Up Running

The years passed and Foden continued his career in the RAF. By 1976, at the age of 49, he had taken up running. He belonged to the Veterans Athletic Club. In 1977, Foden ran in his first marathon. At that time, he was working as a flight instructor. He was assigned to teach cadets on various topics, including first aid, map reading, aircraft, and RAF knowledge.

The years passed and Foden continued his career in the RAF. By 1976, at the age of 49, he had taken up running. He belonged to the Veterans Athletic Club. In 1977, Foden ran in his first marathon. At that time, he was working as a flight instructor. He was assigned to teach cadets on various topics, including first aid, map reading, aircraft, and RAF knowledge.

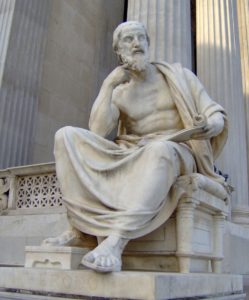

In 1978, Foden was studying for an advanced degree at a university. As part of an assignment, he read about the story of Pheidippides’ run from Athens to Sparta as recorded by Greek historian Herodotus. He read in that history, “Pheidippides was sent by the Athenian generals, and, according to his own account . . . reached Sparta on the very next day.” As a long-distance runner, that caught Foden’s attention. He wondered if the story was true. Herodotus had been criticized for in inclusion of legends and fanciful accounts in his work. A fellow historian accused him of making up stories for entertainment. But many of his tales had been confirmed by modern historians and archaeologists. Foden wondered if Pheidippides’ run was truth or an impossibility as so many had suspected.

Foden explained, “I looked at the map and thought, that is about 150 miles, I’ve never run 150 miles before, I wonder if I can? After that I thought, if I could do the same run to Sparta, I might become famous.” That dream stayed with him for several years.

Foden explained, “I looked at the map and thought, that is about 150 miles, I’ve never run 150 miles before, I wonder if I can? After that I thought, if I could do the same run to Sparta, I might become famous.” That dream stayed with him for several years.

In the meantime, Foden continued to go further and faster. In 1980, at the age of 54, he won a silver medal at the World Masters Athletic Championships in New Zealand.

Foden Begins Ultrarunning

By 1981, Foden was stationed in Germany and began running ultradistances in races around Europe. He ran in the Lauf Unna 100 km in Germany, finished 26th out of 554 finishers, in 9:03:49.

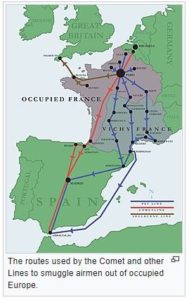

That year he also ran in a very unique relay on a historic European route. He ran in the 750-mile, nine-day Brussels to Spain Escape Marathon. This was a run along a historic World War II Comete escape route through Belgium and France to the Pyrenees Mountains that was used by 800 airman to get to safety. The Comete Line began in Brussels where the airmen were fed, clothed, given false identity papers, and hidden in attics, cellars, and people’s homes. A network of volunteers then escorted them south and passed them from link to link in a chain of local helpers who clothed, fed, and hid them, usually at great personal risk to themselves. The airmen finished the journey into neutral Spain.

That year he also ran in a very unique relay on a historic European route. He ran in the 750-mile, nine-day Brussels to Spain Escape Marathon. This was a run along a historic World War II Comete escape route through Belgium and France to the Pyrenees Mountains that was used by 800 airman to get to safety. The Comete Line began in Brussels where the airmen were fed, clothed, given false identity papers, and hidden in attics, cellars, and people’s homes. A network of volunteers then escorted them south and passed them from link to link in a chain of local helpers who clothed, fed, and hid them, usually at great personal risk to themselves. The airmen finished the journey into neutral Spain.

The 1982 relay that Foden participated in was designed to raise funds for the Royal Air Forces Escaping Society that aided families of continental civilians who gave their lives in helping British fliers escape from the Nazis. The run was organized as a relay of eight airmen from four countries. Each ran 10 km legs over the nine days. Foden remembered, “We met so many interesting people down the route and there were some phenomenal coincidences with those we met.” They received a marvelous reception from people along the way that moved them to tears. This experience certainly must have further sparked his interest in recreating the run made by Pheidippides in Greece.

Also in 1981, Foden ran in the World Championship Marathon Christchurch and had a podium finish. Early in 1982, he ran 100 miles in 31 hours at the Pilgrims Race in Britain.

Plans for the 1982 RAF Expedition.

In 1982, Foden was a Wing Commander in the British Royal Air Force, still based in Germany. He wanted to combine his two passions outside of the service, history and long-distance running.

In 1982, Foden was a Wing Commander in the British Royal Air Force, still based in Germany. He wanted to combine his two passions outside of the service, history and long-distance running.

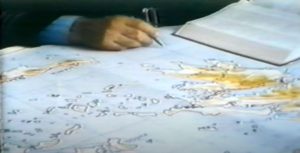

Foden explained, “I got an air navigation map, which showed where the hills were, and with the assistance of some professors of Greek History at Cambridge University we worked out the probable route.”

Foden explained, “I got an air navigation map, which showed where the hills were, and with the assistance of some professors of Greek History at Cambridge University we worked out the probable route.”

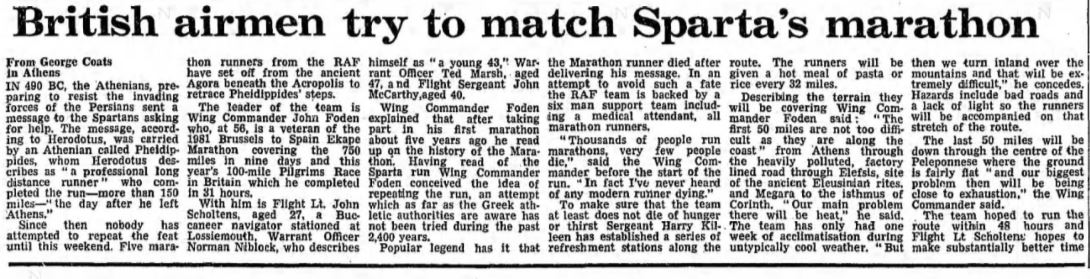

It was reported, “Foden conceived the idea of repeating the ancient run, an attempt which as far as the Greek athletic authorities were aware had not been tried during the past 2,400 years.” When asked why he was doing the run, Foden in later years admitted, “I wanted to be famous, the man who proved an important piece of history was correct.”

Foden said, “My running company thought the whole thing was a bit crazy, because it was beyond their experience. They thought that the marathon was super-human and this was way beyond that.” Reporters were stunned when they heard about this idea. It sounded like a death wish. Foden explained, “Thousands of people run marathons, very few people die. In fact, I’ve never heard of any modern runner dying.”

Foden said, “My running company thought the whole thing was a bit crazy, because it was beyond their experience. They thought that the marathon was super-human and this was way beyond that.” Reporters were stunned when they heard about this idea. It sounded like a death wish. Foden explained, “Thousands of people run marathons, very few people die. In fact, I’ve never heard of any modern runner dying.”

Foden needed to find funding for the expedition and applied for a sizable grant from the RAF. He called it the 1982 RAF Expedition. The Physical Education Officer in charge of approving grants thought the proposal was just a way to get a vacation in Greece. But one his staff was a scholar who was also a runner and took interest in the project. The funding eventually came through. The British embassy then helped to get permission from Greece for Foden to do the run.

Foden needed to find funding for the expedition and applied for a sizable grant from the RAF. He called it the 1982 RAF Expedition. The Physical Education Officer in charge of approving grants thought the proposal was just a way to get a vacation in Greece. But one his staff was a scholar who was also a runner and took interest in the project. The funding eventually came through. The British embassy then helped to get permission from Greece for Foden to do the run.

Foden recruited four other marathon runners in the RAF that were stationed in Germany to join him in the run. Two were from Scotland and the other two from England and Australia. He also recruited six other RAF servicemen to serve as a support crew. All six had marathon experience and included a medical attendant and a cook. A date in October 1982 was chosen and travel with the RAF was arranged. That month was important because it was believed the the battle of Marathon occurred anciently in the Fall. Unfortunately, their flights From Germany to Athens were cancelled indefinitely so he had to rent two “minibuses” (vans) for the trip.

Foden’s wife declined the invitation to go with him to Greece. “My wife thought I was mad. She thought the whole thing was ridiculous and didn’t want to encourage me.”

It was a long and difficult trip that passed through Communist-occupied Yugoslavia. They had hoped to get to Greece sooner, in order to scout out the route carefully, but they only had a week to prepare. Before he left Germany, Foden was able to get an air navigation map that included Greece, but it was still too small of scale, so he had to adapt and propose a route in the days leading up to the run.

The First Five Runners

The five runners who took part in the historic 1982 run in Greece were:

- Ted Marsh, age 47, was a Warrant Officer.

- John Harold Scholtens, age 27, primarily stationed in Lossiemouth, Scotland. He was a flight Lieutenant and served as a “Buccaneer navigator.”

- John Foden, age 56, was a Wing Commander stationed in Germany. He was oldest, but also the most experience runner in that group, and in charge of the route.

- Norman Niblock was an Air Electronics Operator also primarily stationed in Lossiemouth, Scotland, who described himself as “a young 43.”

- John McCarthy, age 40, was a Flight Sergeant. He already had some ultrarunning experience. He ran in the 1982 Vogelgrun 100 km in France and finished 32nd out of 65 runners with a time of 10:11:31.

Crew from Campion School in Athens

With only a day to go, the British Embassy in Athens contacted Campion School in Athens to see if they could provide additional support for the RAF expedition.

With only a day to go, the British Embassy in Athens contacted Campion School in Athens to see if they could provide additional support for the RAF expedition.

Campion was an English-language international school with a British curriculum adapted to make full use of the location and culture of Greece. It was established in 1970. There was a wide range of competitive sports to offer at the school, including cross-country running. It was hoped to find runners and guides familiar with the country who could lend valuable support along the way.

A team of six from the school volunteered to be part of the adventure, including four teachers and two students. The teachers were Phil Simmonds (art teacher), Dave Ireland (the school team organizer), Rob Biggs, and Andy Birch. The two students were Nick Papageorge (age 18), and Ian Katsivalis (age 16). The four teachers did not speak Greek, but the two students did.

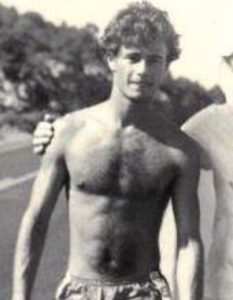

Nick Papageorge

Nick Papageorge (1964-) was born and raised in Kenya to parents with Greek ancestry and lived among Greeks. His family moved to Greece when he was thirteen years old and he started to attend the Campion School. He ran his first marathon in 1980 at the age of sixteen. Papageorge would be a key member of the team that provided many miles of pacing. He said, “I used to do a lot of cross-country running and hang out a lot with the teachers through running, football and rugby. I also was a member of the Hash House Harriers, a social running club. Somehow the teachers were contacted by the embassy in Athens that the RAF group was doing this run and they needed some support, if we could help.” The school was enthusiastic and scrambled to get ready to help.

Nick Papageorge (1964-) was born and raised in Kenya to parents with Greek ancestry and lived among Greeks. His family moved to Greece when he was thirteen years old and he started to attend the Campion School. He ran his first marathon in 1980 at the age of sixteen. Papageorge would be a key member of the team that provided many miles of pacing. He said, “I used to do a lot of cross-country running and hang out a lot with the teachers through running, football and rugby. I also was a member of the Hash House Harriers, a social running club. Somehow the teachers were contacted by the embassy in Athens that the RAF group was doing this run and they needed some support, if we could help.” The school was enthusiastic and scrambled to get ready to help.

The Start

On October 8, 1982, Foden, age 56, and the other RAF officers started out at Athens at dawn, at 7 a.m. They began their run at the edge of the ancient Agora marketplace that lies beneath the Temple of Hephaestus. Anciently, this marketplace was the primary meeting ground for Athenians, where business was conducted, a place to hang out, watch performers, and listen to famous philosophers.

It was reported, “Five marathon runners from the Royal Air Force have set off from the ancient Agora beneath the Acropolis to retrace Pheidippides’ steps.” The goal was to finish in less than 36 hours. Foden said, “It was really a test initially because I didn’t know if I could do it. I was very uncertain, but I was determined to do it.”

Foden recalled, “Once I started running, I had to forget about everything else and concentrate on one thing alone, and that was to get to Sparta.”

The First Day

The five runners tried to follow the route that Foden had researched, which went both on paved road and cross country on ancient military routes. Going out of the large city of Athens, dogs would come out in the shantytowns and snap at them. The first section from Athens had heavy traffic on the roadways and was heavily polluted, with factories lining the roads belching smoke.

The five runners tried to follow the route that Foden had researched, which went both on paved road and cross country on ancient military routes. Going out of the large city of Athens, dogs would come out in the shantytowns and snap at them. The first section from Athens had heavy traffic on the roadways and was heavily polluted, with factories lining the roads belching smoke.

Foden said, “The course was along shepherd’s footpaths and stony farm tracks, not so very different to those Pheidippides probably used. Even parts of the road along the coast to Corinth were so bad it was little better than a farm track. Well over half the course was what the British and Americans would call a trail.”

Foden said, “The course was along shepherd’s footpaths and stony farm tracks, not so very different to those Pheidippides probably used. Even parts of the road along the coast to Corinth were so bad it was little better than a farm track. Well over half the course was what the British and Americans would call a trail.”

The RAF crew of six, in two vans. tried to follow along on nearby roads. “To make sure that the team does not die of hunger or thirst, Sergeant Harry Killeen has established a series of refreshment stations along the route. The runners will be given a hot meal of pasta or rice every 32 miles.” They also fed on military meals ready to eat along the way.

Foden explained that their main problem during the first stretch was the heat. The runners had hoped to acclimatize to the hotter Greece weather, but their one week in Greece had had been untypically cool weather.

“The five runners initially stuck together, trying to protect one another and covering each other’s backs.” Later, they became split up and ran at their own paces, making things more difficult for the support crew. Marsh, ahead, had no food all the way to the Corinth Canal (about mile 52), so he had to buy some from a shop. “John McCarthy was so thirsty at Zevgolation, he tried to drink from a tap at a petrol station. But the owner set his dogs on John to chase him away.”

Niblock dropped out early before Corinth (about 85 km/52 miles) because an old knee injury was giving him pain.

The Campion School Crew Joins In

It wasn’t until later in the day that the six helpers from Campion School joined in. The teachers brought two cars they owned to make the rugged trip, two very old Mercedes. Papageorge explained, “We heard that the runners had started at 7 o’clock in the morning, outside of Athens, just as the sun was rising below the Acropolis. After school, we met up with them about 4 p.m., just past Corinth, about the 80 km mark, at the Corinth Hellas Can Factory.”

Papageorge initially paced Marsh during the early evening. They plodded along and talking about many things along the way. But Marsh gave up about 40 km later near Nemea because of a bad sunburn. He also knew that he had gone out too fast and was very disappointed. Marsh and Papageorge jumped into the car driven by one of the teachers.

The team from the school had a great time along the way, drinking beer, playing loud music, and stopping at cafes. At one cafe the beer was cheaper than water. The two Greek-speaking students were a great asset to have along because once out in the rural villages, the people only spoke Greek.

The team from the school had a great time along the way, drinking beer, playing loud music, and stopping at cafes. At one cafe the beer was cheaper than water. The two Greek-speaking students were a great asset to have along because once out in the rural villages, the people only spoke Greek.

Things were confusing as the runners were spread out, supported by the four vehicles that would go ahead, wait, and at times go back looking from them. Papageorge recalled, “There weren’t any check points. The RAF expedition was pretty badly planned for an RAF expedition.”

Navigation was a difficult challenge. Foden explained, “Y-junctions were the bane of our lives as we had only the vaguest idea of Greece’s geography, and notices pointing to different destinations meant nothing to us. Moreover, we only had an air navigation map, because accurate ground maps had been declared secret as a result of the recent Turkish invasion of Cyprus.”

Navigation was a difficult challenge. Foden explained, “Y-junctions were the bane of our lives as we had only the vaguest idea of Greece’s geography, and notices pointing to different destinations meant nothing to us. Moreover, we only had an air navigation map, because accurate ground maps had been declared secret as a result of the recent Turkish invasion of Cyprus.”

Running Through the Night

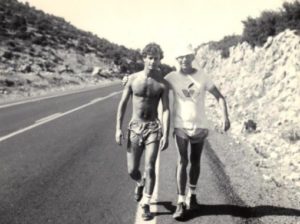

Foden said, “We turned inland over the mountains and that was extremely difficult.” The roads were bad in the dark. The car Papageorge rode in caught up with runner McCarthy. Papageorge paced him late into the night, until after midnight.

Foden said, “We turned inland over the mountains and that was extremely difficult.” The roads were bad in the dark. The car Papageorge rode in caught up with runner McCarthy. Papageorge paced him late into the night, until after midnight.

Papageorge recalled, “I remember running a long way with him, going through some valleys. At one point, we were running through a field trying to go more or less in the right direction. We stopped at some point to stop to eat and drink, and then we heard some local hunters shooting out in the dark. We thought that they were shooting at us. We ended up legging it across this field and getting to the bushes on the other side, getting back onto the road, and continuing on.” They caught up with the car and Papageorge traded off pacing duties with someone else.

Foden remembered, “Navigating at night and in the gray murk of dawn was tricky. Complicating matters, radio contact between the two support vehicles was lost in the mountains, and their ability to communicate with each other was severed.”

Dogs were probably their most severe danger. “These were a nuisance at all the country villages. We armed ourselves with stones to throw at the mongrels and skirted the villages to avoid them. This meant stumbling across fields in the dark as the tracks went straight into the villages.”

Dogs were probably their most severe danger. “These were a nuisance at all the country villages. We armed ourselves with stones to throw at the mongrels and skirted the villages to avoid them. This meant stumbling across fields in the dark as the tracks went straight into the villages.”

Up over the Mountain

The runners and crews made a 3,000-foot ascent of Mount Parthenion via Sangas Pass during the dead of night. This a mountain, covered with rocks and bushes, was the place where Pheidippides met the god Pan during his run. Pan told Pheidippides that he would help the Athenians at Marathon if they turned back to worship him as in times past.

The runners and crews made a 3,000-foot ascent of Mount Parthenion via Sangas Pass during the dead of night. This a mountain, covered with rocks and bushes, was the place where Pheidippides met the god Pan during his run. Pan told Pheidippides that he would help the Athenians at Marathon if they turned back to worship him as in times past.

Foden described, “At night I mistook a dried upriver bed leading down the valley for the track to Maladrenion. It took a long while for me to work out what had gone wrong. John McCarthy also got lost hereabouts. By then the three of us still running were spread over about twenty miles and when we reached the pass had to individually find our way over it without any aids except the moonlight shining on stones polished by shepherd’s boots over the centuries. It was very eerie to be high up a mountain at night in a foreign country and far from certain that we were on the correct path.”

Foden described, “At night I mistook a dried upriver bed leading down the valley for the track to Maladrenion. It took a long while for me to work out what had gone wrong. John McCarthy also got lost hereabouts. By then the three of us still running were spread over about twenty miles and when we reached the pass had to individually find our way over it without any aids except the moonlight shining on stones polished by shepherd’s boots over the centuries. It was very eerie to be high up a mountain at night in a foreign country and far from certain that we were on the correct path.”

Papageorge, in Birch’s old Mercedes. pushed up the mountain on steep and rough switch-back roads. “We drove up quite far. It was a full moon, and we were listening to Pink Floyd’s ‘Dark Side of the Moon.’ Up there was one of the RAF vans, up as far as it could get, with John Foden in all sorts of trouble. He was irritated and he was quite broken. One of the RAF crew was trying to get him to stop and pull out. He would have nothing of it. He was very stubborn. He swore and went around to the back of the van for a bathroom break, came back and said, ‘I’m off,’ and off he went.” Papageorge got back in the car for much needed sleep.

Foden admitted, “I nearly collapsed halfway and was very ill. We did not see many people. There were no roads for a section and all I was doing was following goat tracks and to know where I was going, I had to look for the north star. I was on a runner’s high for the first 100 miles. I was getting really pleased with myself. It gave me the courage and confidence to keep going.”

Foden admitted, “I nearly collapsed halfway and was very ill. We did not see many people. There were no roads for a section and all I was doing was following goat tracks and to know where I was going, I had to look for the north star. I was on a runner’s high for the first 100 miles. I was getting really pleased with myself. It gave me the courage and confidence to keep going.”

The Second Day

For much of the second day, Papageorge ran with Foden. They ran together in the morning as the sun was coming up and the fog was dissipating. Papageorge said, “Early in the morning, I recall Foden told me the story of Pheidippides meeting the God Pan. I remember talking about it a lot. I was only 18, but remembered that he was eccentric, but very knowledgeable. He knew a lot of stuff. I ran with him for a long, long while.”

The last fifty miles were down through the center of the Peloponnese, where the ground was fairly flat. Foden said, “I ran from Sangas to Tegea on the second morning in considerable heat for about five hours without a drink, because our support vehicle could not find me. I was reduced to a slow walk. In those days the only road to Tripoli and Sparti was via Argos, so our support vehicle had to make a 100 kms detour, during which it lost all contact with us, and we were already causing it trouble by being so spread out.”

Foden did not mind that they were faced with challenges. “In that sense, we were rather pleased that it wasn’t easy, because we thought that it made it much more realistic to what Pheidippides himself would have had to do when he just wouldn’t have been able to carry enough water and food himself to cover the whole distance.”

For the last 50 kilometers, they ran on the road from Tegea to Sparta. Foden had not had enough time before the run to research this section to look for ancient military roads, so they ran on the modern road.

Foden caught up with McCarthy and Papageorge traded off to pace McCarthy. “I ran a little bit with him and then he was in all sorts of trouble. He was really unable to stay awake or run more than a little bit. He was got massaged by the physiotherapist, got back in the car, and tried to sleep for a bit. He was very, very tired. But he was very gritty and continued.”

The Finish

In the early evening of the second day, Foden neared Sparta. There was one final climb. He said, “I hated that. I nearly couldn’t do it. Having gone all that way, I suddenly felt that I could not run up this bloody hill.” But he made it over the hill and then was surprised at the reception that he received as he approached the city. He said, “When I ran, no one knew what I was doing until I got near to Sparta. Suddenly there were lots of people all over the place.”

In the early evening of the second day, Foden neared Sparta. There was one final climb. He said, “I hated that. I nearly couldn’t do it. Having gone all that way, I suddenly felt that I could not run up this bloody hill.” But he made it over the hill and then was surprised at the reception that he received as he approached the city. He said, “When I ran, no one knew what I was doing until I got near to Sparta. Suddenly there were lots of people all over the place.”

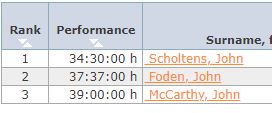

Scholtens was the first to finish, in 34:30. “For Scholtens, there was a rousing cheer from the locals as he entered the sports stadium in Sparta to cross the finish line.”

Foden finished his modern reenactment of the run from Athens to Sparta in the dark at 37:37. The Greeks who cheered him at the finish surprised them with crowns of olive leaves “I just didn’t know what to say. I said, ‘We’ve proved a part of your history is true, the Herodotus was a reliable historian.’”

Papageorge said of Foden, “For me as a kid, when I saw him up on the mountain and his attitude when I was running with him, for him it was not just to prove that the history was true, it was more of a case of winning the day. He was so stubbornly after that.”

Foden insisted in later years that Scholtens had gone off the planned route, taking a ten-mile short cut, helping him to finish first. He claimed that Scholtens had followed a nearly direct course and avoided climb to the pass on Mount Parthenio. In fairness, all the runners got lost, especially Scholtens, and took wrong turns in the towns, so extra miles were experienced by all. McCarthy finished in third, an hour and a half after Foden, in 39:00. He had become lost and ran about seven miles further than Foden. A popular myth that grew out of Foden’s run was that he finished in less that 36 hours, but he did not.

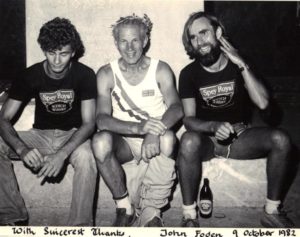

The three runners were thrilled to just sit down to rest on the steps at the foot of the bronze statue of Leonidus at the end of Main Street and just rest. Between the three of them, they had lost a total of 40 pounds. Papageorge paced them for many, many miles of the journey and Foden was deeply grateful for the assistance.

After the Run

Foden told the Greeks around him, “You need to make the route we have run, a race.” But at first, he didn’t seriously think a race would be organized soon. They never dreamed for one moment what a monumental classic like the Spartathlon would grow out of their pioneer run.

The next day, the entire group got together again to take pictures at the statue. John McCarthy was still suffering. Papageorge remembered that Foden stunned his RAF team with a proposal.

Papageorge listened carefully, “Foden said, ‘Let’s walk back to Athens.’ Everyone said, ‘Why, what for?’ He said, ‘That way we can prove that’s what Pheidippides did, because he walked back.’ He said that as a professional messenger, Pheidippides was allowed to eat at any inn or private house, to go in and get their food, water, wine or anything they wanted. Foden said, “We’ve got to prove that this was possible. So, let’s walk back.” Everybody said ‘No, we cannot do it.’ It was a bit strange. I was just a kid, and I could feel the tension. But Foden was quite adamant to do it even without support over three-four days. Fortunately for the whole expedition, they talked him against it.”

The school crew hung out in Sparta during the day, had some dinner and then drove back to Athens. The RAF team later met at the British embassy in Athens and had an awards ceremony, attended by the Campion School teachers. A week later, the five runners ran in the Athens marathon and then returned to Germany. After that they went their various ways and never did hold a reunion. Foden made a report to the RAF on their ‘military exercise.’

Foden’s Later Life

Foden went on to help organize the Spartathlon for the first four years. Since he was in the Air Force, he could not go to Greece each year, so he had to stop and turn it over. Also, his wife did not want him to do it. All his running had become quite a subject of contention that he said had almost resulted in divorce.

Foden went on to help organize the Spartathlon for the first four years. Since he was in the Air Force, he could not go to Greece each year, so he had to stop and turn it over. Also, his wife did not want him to do it. All his running had become quite a subject of contention that he said had almost resulted in divorce.

Foden became a driving force in ultrarunning in the UK and an active member of the Road Runners Club. In 1987, Foden organized and was the race director of a 24-hour race held indoors at the Milton Keynes Mall in England. In 1989 his old friend John McCarthy ran there. In 1990 the race was the IAU International 24-hour Championships.

In 1989 Foden also organized the Nottingham 100 km races around a rowing lake at the National Watersports Centre in Holme Pierrepoint, Nottingham. He directed that race through 1993. Several of his 100 km races were National Championships. He would produce a very comprehensive results booklet that included all the finishers and non-finishers with their lap time. He also founded the Anglo Celtic Plate 100k which is still contested today by England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland.

In 1989 Foden also organized the Nottingham 100 km races around a rowing lake at the National Watersports Centre in Holme Pierrepoint, Nottingham. He directed that race through 1993. Several of his 100 km races were National Championships. He would produce a very comprehensive results booklet that included all the finishers and non-finishers with their lap time. He also founded the Anglo Celtic Plate 100k which is still contested today by England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland.

In 1992, the Spartathlon organization awarded Foden a plaque and medal for his ten years of Spartathlon service and recognized him as been the founder and first runner of Spartathlon.

In 1992, the Spartathlon organization awarded Foden a plaque and medal for his ten years of Spartathlon service and recognized him as been the founder and first runner of Spartathlon.

In 1994 Foden was secretary of the Ultra Running Committee of the British Athletic Federation. At the age of 68, he entered an 80-mile World Trail-Running Championship race in Sussex with five hundred others.

In 2002, Foden organized a 100-mile track race at the Crystal Palace in London to celebrate Don Ritchie’s 100-mile world record run on that same track 25 years earlier (see episode 72). He was the race director and was very pleased with the battle and thrilling finish by the Russian runners during the event.

In 2002, Foden organized a 100-mile track race at the Crystal Palace in London to celebrate Don Ritchie’s 100-mile world record run on that same track 25 years earlier (see episode 72). He was the race director and was very pleased with the battle and thrilling finish by the Russian runners during the event.

When talking about ultrarunning, Foden said, “I’ve never known an ultrarunner to talk about hitting the wall, which is the favorite topic of conversation among marathon runners. The art of it is to learn what is the fastest speed you can run at so that you don’t get to 70 km and simply run out of all forms of energy as that’s when you just flap around.” He joked that his knees were now “disgustingly decrepit” and that his withdrawal symptoms from running were so bad when injury, weather or common sense kept him off the road, that he “took to the bottle.”

When talking about ultrarunning, Foden said, “I’ve never known an ultrarunner to talk about hitting the wall, which is the favorite topic of conversation among marathon runners. The art of it is to learn what is the fastest speed you can run at so that you don’t get to 70 km and simply run out of all forms of energy as that’s when you just flap around.” He joked that his knees were now “disgustingly decrepit” and that his withdrawal symptoms from running were so bad when injury, weather or common sense kept him off the road, that he “took to the bottle.”

Into his late 80s, Foden said, “When I finally die, there is going to be something in this world that I left behind. Something that people will remember me for.” When he looked at what the Spartathlon evolved into, he wrote, “What had been an adventure expedition in a country whose language none of us spoke, has slowly become an internationally renowned road race. It is now similar in style to the marathon, but many times more challenging. Like the marathon it is based on Greek history, but it was the brain-child of foreigners.”

Into his late 80s, Foden said, “When I finally die, there is going to be something in this world that I left behind. Something that people will remember me for.” When he looked at what the Spartathlon evolved into, he wrote, “What had been an adventure expedition in a country whose language none of us spoke, has slowly become an internationally renowned road race. It is now similar in style to the marathon, but many times more challenging. Like the marathon it is based on Greek history, but it was the brain-child of foreigners.”

Foden ran for the last time in 2000. Later that year he experienced a stroke that left him partially paralyzed. Foden’s wife tragically became disabled as a result of a car crash they were in and passed away in 2001. John Foden died on October 21, 2016, at the age of 90.

The Other Runners

What about the other four who ran in 1982? What happened to them? John Scholtens went on to run London to Brighton twice, in 1983 and 1988, but then quit ultrarunning. He passed away in his early 60s. John McCarthy remained active in ultrarunning through the 1980s, running Spartathlon again in 1985. In 1989 he ran in a 24-hours indoor race at the Milton Keynes Mall in England, reaching 116 miles. Norman Niblock, with his problem knee, did not continue running ultra-distances and passed away in 2015 at the age of 76. Ted Marsh ran London to Brighton in 1975.

Nick Papageorge, the young pacer, graduated from Campion School in Greece the summer after the 1982 run and then went to college in England. He continued running but did not hear about the establishment of the formal Spartathlon for several years. He started running again and did triathlons and then settled in Denmark and worked in Information Technology. He took up ultrarunning in 2012, qualified for Spartathlon by running a 10:22:02 100 km in Copenhagen. He ran in the 2013 Spartathlon but had to stop after 70 km which was very disappointing to him. But he followed that by running 113 miles in a 24-hour race in Spain. Papageorge reflected back, “It was amazing when I think back how privileged we were, all of us, not only the two kids including myself, doing these things out of nowhere, to be part of modern history which is related to ancient history.”

Spartathlon was born! Just as serviceman proved that the Western States course could be covered in less than two days ten years earlier in 1972, servicemen again contributed toward ultrarunning history in 1982 by pioneering Spartathlon.

Next

Just four months after the 1982 RAF Expedition, in February 1983, the Greek Athletic Association announced that a Spartathlon would be held on September 30, 1983. The next episode tells the tale of the first formal Spartathlon in 1983.

Sources:

- Interview with Nick Papageorge, Sep 17, 2021

- Evening Standard (London, England), Aug 7, 1956

- North Wales Weekly News (Denbighshire), Jun 2, 1977

- Lynn Advertiser (King’s Lynn, England), Oct 27, 1981

- Aberdeen Press and Journal (Scotland), Oct 13, 1982

- The Guardian (London, England), Oct 11, 1982, Feb 4, 1983, Jun 24, 1994

- Spartathlon Historical Information

- John Foden documentary – ULTRA

- In the Footsteps of Pheidippides – 1983 footage

- Dean Karnazes, The Road to Sparta

- From the Newsletter of Spartathlon Club of the British Isles 1998/1999

- Australian War Memorial, James Clement Foden

- Spartathlon 30 Years. The footsteps of a Legend

- Peter Krenz, The Battle of Marathon (Yale Library of Military History)