Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 28:48 — 34.3MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

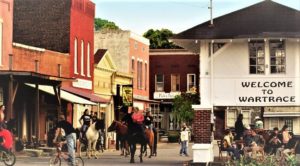

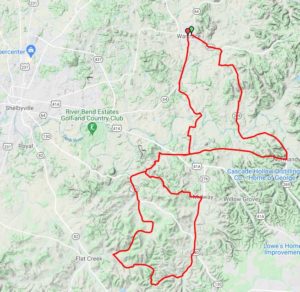

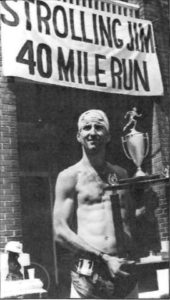

The Strolling Jim 40, held in Wartrace, Tennessee, is one of the top-five oldest ultras in America that is still being held to the present-day (2021). It is a road race that runs on very hilly paved and dirt roads, the brainchild of Gary Cantrell (Lazarus Lake). Because its distance is a non-standard ultra-distance of 41.2 miles, the race perhaps has not received as much publicity as it deserves among the ultrarunning sport. But buried within, is a storied history along with a seemly unbreakable course record set in 1991 by Andy Jones of Canada (and Cincinnati, Ohio), one of the greatest North American ultrarunners who most of the current generation of ultrarunners have never heard of before.

The Strolling Jim 40, held in Wartrace, Tennessee, is one of the top-five oldest ultras in America that is still being held to the present-day (2021). It is a road race that runs on very hilly paved and dirt roads, the brainchild of Gary Cantrell (Lazarus Lake). Because its distance is a non-standard ultra-distance of 41.2 miles, the race perhaps has not received as much publicity as it deserves among the ultrarunning sport. But buried within, is a storied history along with a seemly unbreakable course record set in 1991 by Andy Jones of Canada (and Cincinnati, Ohio), one of the greatest North American ultrarunners who most of the current generation of ultrarunners have never heard of before.

The classic Strolling Jim 40 came back into ultrarunning focus during early May 2021, when Andy Jones’ remarkable record was finally broken by Zack Beavin, of Lexington, Kentucky. The story of Strolling Jim must be told along with the progression of its famed course record.

Who was Strolling Jim?

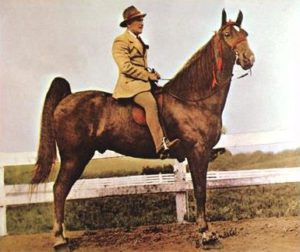

Strolling Jim (1936-1957) was the first Tennessee Walking Horse to become a National Grand Champion show horse for his breed. He was first trained to pull a wagon and a plow until he was noticed by a well-known Walking Horse trainer, William Floyd Carothers (1902-1944), who owned the Walking Horse Hotel in Wartrace, Tennessee. Carothers thought the horse had potential and bought him for $350 and started training him.

In 1939, Strolling Jim competed and won at the Tennessee Walking Horse National Celebration held at Wartrace, Tennessee. He went on with a very successful show career around the U.S., retiring in 1948 in Tennessee. He died in 1957 and was buried by his stables behind the Walking Horse Hotel in Wartrace.

In 1939, Strolling Jim competed and won at the Tennessee Walking Horse National Celebration held at Wartrace, Tennessee. He went on with a very successful show career around the U.S., retiring in 1948 in Tennessee. He died in 1957 and was buried by his stables behind the Walking Horse Hotel in Wartrace.

Idea for a Race

In 1979, Gary Cantrell (1954-), of Shelbyville, Tennessee, was an accounting student at Middle Tennessee State University. He was a veteran of eight marathon finishes and wanted to run in an ultra. But at the time, there were few being held in the South. So, he decided to put on his own ultra for his Horse Mountain Runners Club who trained around the Wartrace, Tennessee area. John Anderson, 29, a sub-3-hour marathoner from Bell Buckle, Tennessee remarked, “Gary and I wanted to run an ultramarathon and so we decided to put on one of our own. He got out the maps and lined out a course. At first, I thought we should call it the ‘Idiots Run,’ but I believe Gary came up with a more appropriate name.”

They decided to start Strolling Jim 40 in the town of Wartrace, nicknamed the “Cradle of the Walking Horse.” Cantrell said, “The course is mostly hills, and I believe for a runner to finish the race it will be less what’s in the legs and more of what’s in the mind. It is about 90 percent mental. It will pretty much be up to each runner to make it on his own. Runners will have to run with the course rather than at it.”

They decided to start Strolling Jim 40 in the town of Wartrace, nicknamed the “Cradle of the Walking Horse.” Cantrell said, “The course is mostly hills, and I believe for a runner to finish the race it will be less what’s in the legs and more of what’s in the mind. It is about 90 percent mental. It will pretty much be up to each runner to make it on his own. Runners will have to run with the course rather than at it.”

The news reported, “The race will be anything but a stroll. The 40-mile loop begins near the well house which guards the old sulfur and mineral water source near the middle of the town. The course winds through rural Bedford County communities before heading back to the finish line in front of the Walking Horse Hotel. Along the route numerous hills will furnish tortuous entertainment for the ultramarathoners.”

The news reported, “The race will be anything but a stroll. The 40-mile loop begins near the well house which guards the old sulfur and mineral water source near the middle of the town. The course winds through rural Bedford County communities before heading back to the finish line in front of the Walking Horse Hotel. Along the route numerous hills will furnish tortuous entertainment for the ultramarathoners.”

Cantrell added, “It’s an isolated backwaters place that has changed little in this century.” He was surprised that many wanted to run the difficult race. “Six or eight doctors will be in the race and that sort of surprised me. You’d think of all people they’d know better.”

Inaugural Race Entrants

Ronald Moore (1946-), of Hermitage, Tennessee signed up for the race and planned feed on plenty of dates along the way. He said, “I intend to try and blend in with the course and just try to finish. I’ve been looking for a challenge and this course is really an obstacle. I guess I am kind of foolish for trying at race this far. The fellows at work think I’m crazy, but if I make the 40-mile run, then I would like to shoot for a 100-miler.”

Cantrell had been training about ten miles a day with a 30-mile run every-other week. His wife, Mary, was also among the entrants. She had been training up to 70 miles a week and said, “I began doing more training than Gary was, and I thought to myself, ‘Well if Gary thinks he can do it, then I believe I can too. I guess I just got caught up in the excitement of it all and maybe I’m a little crazy.”

The 1979 Strolling Jim 40

The inaugural race was held on May 5, 1979. A pre-race spaghetti dinner was held the night before at the 62-year-old Walking Horse Hotel, Dozens of pictures of Tennessee Walking Horses adorned the dining room walls along with Strolling Jim’s bridle that he wore when he won his national title. Bluegrass musicians furnished entertainment during the dinner playing guitars, banjos, and fiddles.

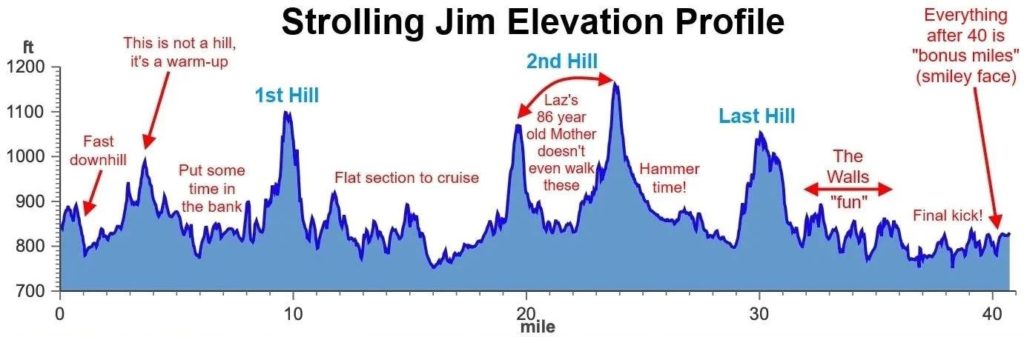

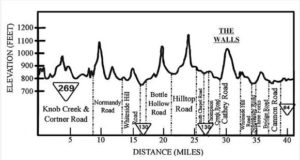

The hilly figure-eight 40-mile road course (actually 41.2 miles) initially was 75% on paved roads and 9.7 miles up and down gravel roads. It climbed about 2,300 feet along the way. The most infamous part of the course was the “Walls” section near the 29-mile mark that consisted of 3.5 miles of steep, rough, rocky roads. Cantrell described, “This section has it all: precipitous climbs and descents, a rocky and muddy surface, and even a creek or two to jump.” The paved roads were by no means easy. Most of them were in need of a lot of repair and hard to run on evenly.

The hilly figure-eight 40-mile road course (actually 41.2 miles) initially was 75% on paved roads and 9.7 miles up and down gravel roads. It climbed about 2,300 feet along the way. The most infamous part of the course was the “Walls” section near the 29-mile mark that consisted of 3.5 miles of steep, rough, rocky roads. Cantrell described, “This section has it all: precipitous climbs and descents, a rocky and muddy surface, and even a creek or two to jump.” The paved roads were by no means easy. Most of them were in need of a lot of repair and hard to run on evenly.

For that first year Cantrell used streamers to mark the course and set out water jugs every five miles. But crews were also required to drive along and provide support. Twenty-two runners started that first year and only two had finished an ultra before.

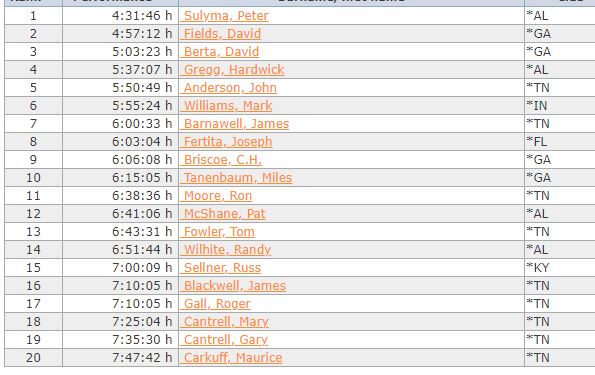

Peter Sulyma (1945-) a NASA aerospace engineer, of Huntsville, Alabama took the lead, hit the marathon mark in 2:45:23 and finished first with 4:31:46. Dave Field of Columbus, Georgia finished second with 4:57:12. The only woman finisher was Mary Cantrell in 7:25:30 and Gary finished ten minutes later for his first ultra finish. Only two runners did not finish.

Peter Sulyma (1945-) a NASA aerospace engineer, of Huntsville, Alabama took the lead, hit the marathon mark in 2:45:23 and finished first with 4:31:46. Dave Field of Columbus, Georgia finished second with 4:57:12. The only woman finisher was Mary Cantrell in 7:25:30 and Gary finished ten minutes later for his first ultra finish. Only two runners did not finish.

Despite the difficulty of the race, with 90 hills, Strolling Jim 40 continued to have a high finishing rate the next year in 1980 when 21 of 22 starters finished. The winners were again Peter Sulyma with a new course record of 4:23:12 and Mary Cantrell with 6:46:32. In 1981 Sulyma accomplished the “three-peat” by triumphing again in 4:36:18 by a wide margin. The race that year grew to 27 starters with 25 finishers. Cantrel warned the crews that if they stirred up dust on the gravel roads, they would be shot. A cow in the road held up the race that year for a few minutes. H.B. Reed, age 57, ran 20 miles of the race barefoot and finished last.

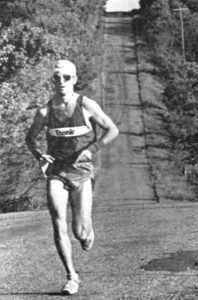

Sulyma continued to develop as a dominant southern ultrarunner. In 1982 at Strolling Jim, Sulyma was leading after 23 miles but felt an unusual health problem that caused him to drop out. He said, “Things started going down hill from there. Running kind of saved my life. When you are training every day, you know exactly what your body can and can’t do.”

Sulyma continued to develop as a dominant southern ultrarunner. In 1982 at Strolling Jim, Sulyma was leading after 23 miles but felt an unusual health problem that caused him to drop out. He said, “Things started going down hill from there. Running kind of saved my life. When you are training every day, you know exactly what your body can and can’t do.”

He was soon diagnosed with Hodgkins Disease, underwent chemotherapy and thought he wouldn’t be able to run for a year. But after two months of doing well, he was given the green light to resume training and run in shorter races. He said, “This is something I’d like people with cancer to realize. I was able to run, a little slower, but I was able to run and run races.”

He was soon diagnosed with Hodgkins Disease, underwent chemotherapy and thought he wouldn’t be able to run for a year. But after two months of doing well, he was given the green light to resume training and run in shorter races. He said, “This is something I’d like people with cancer to realize. I was able to run, a little slower, but I was able to run and run races.”

Sulyma returned to Strolling Jim in 1984 and finished in 5:57:10. He also finished a 100-miler that year with an impressive time of 17:30:55. His cancer went into remission and he continued to run ultras until 1991 when he finished 5th at Strolling Jim with 5:06:51 at the age of 45.

Strolling Jim Grows

In 1983, Strolling Jim grew to 61 starters. The day before the race, Cantrell conducted a driving tour of the course described by Steve Jaber (1951-) of Mill Valley, California. “A procession of about 12 cars on the roads is unusual here and everywhere we stopped, people came out of their houses to see what was happening. Gary Cantrell was in the lead car and he would stop every so often to make important announcements, such as, ‘a major hill starts here,’ or ‘it gets worse ahead.’ Upon return to the old hotel, we checked in and sat down to a wonderful all-you-can-eat spaghetti dinner. This run is a big deal in Wartrace, and everyone’s hospitality and friendliness was just what one would expect from a small southern town.”

In 1983, Strolling Jim grew to 61 starters. The day before the race, Cantrell conducted a driving tour of the course described by Steve Jaber (1951-) of Mill Valley, California. “A procession of about 12 cars on the roads is unusual here and everywhere we stopped, people came out of their houses to see what was happening. Gary Cantrell was in the lead car and he would stop every so often to make important announcements, such as, ‘a major hill starts here,’ or ‘it gets worse ahead.’ Upon return to the old hotel, we checked in and sat down to a wonderful all-you-can-eat spaghetti dinner. This run is a big deal in Wartrace, and everyone’s hospitality and friendliness was just what one would expect from a small southern town.”

Some aid was provided that year by the race, but crews also drove along, offering liquids to all the runners. Even local spectators were out in their trucks with water and Gatorade. Cantrell had a great view of the front-runners, riding in the lead car. He knew it would be a good race that year and said, “The only problem I can foresee is keeping the sponsors out of the beer kegs until the runners finish.”

At the finish, Cantrell presented each runner with a card that had their time and place on it. Jabar wrote, “After the final runners came in, everyone merged on the beer and food. Various public official spoke and gave out trophies, and then Gary called everyone up to present them with individual trophies. It is always nice to get something other than a shirt. After the ceremony, all returned to the feast and talk of this and future runs.” A record 55 runners finished in 1983.

1985 Record Assault

By 1985, Strolling Jim was attracting elite ultrarunners who had their eyes on breaking Sulyma’s 1980 course record of 4:23:12 which had a special status among southern ultrarunners. Many had tried to break it before, but no one had come seriously close. But Tom Zimmerman, age 27, from Minnesota came onto the 1985 stage. Zimmerman was a solid 50-mile ultrarunner who would place 6th later that year against international competition at London to Brighton. Also in the Strolling Jim field of 72 runners, were dominant southern ultraunners, Ray Krolewicz (1955-) of South Carolina and Steve Warshawer (1957-) of Georgia. The race had become so popular that the number of entrants started to be capped that year.

Krolewicz, as usual blasted into the lead with a first mile of 6:33 up several hills, followed by Zimmerman nine seconds back and Warshawer, another thirteen seconds behind. At that point Zimmerman shifted into another gear and left the field behind. A bull chased Sulyma and Washawer for about a half-mile at 6:15 pace before it “crashed and burned on the side of the road, another victim of the tough course.”

Cantrell wrote, “As Zimmerman rippled on toward the last major obstacle (the dreaded ‘Walls’ from 29 to 33 miles) he took his first taste of Tennessee heat. Three miles of flat exposed backtop allowed the sun to work on Tom. He had run off and left the field so far behind that even his aid crew couldn’t keep up. He stepped on the gas and flew up the Walls well under record pace.”

But with temperatures above 80 degrees, Zimmerman sagged as he continued to try to press hard. “When he hit the blacktop, two miles from the finish, the record was still in his hands. But two miles can take an eternity, and those two miles were too much.” He finished in 4:23:29, just 17 seconds over the record. Ten yards past the finish, he collapsed in a heap and requested fluids. He had said it was the most painful race of his career.

1987 Course Record Broken

The 1987 field included a dozen runners who had run a sub-2:40 marathon, sub-6-hour 50 miler, or both. Many of them had high hopes and Zimmerman was back with a focus on breaking the record that had eluded him two years earlier. Krolewicz claimed the early lead but could not create much of a gap ahead of the other front-runners and settled back with the others.

The 1987 field included a dozen runners who had run a sub-2:40 marathon, sub-6-hour 50 miler, or both. Many of them had high hopes and Zimmerman was back with a focus on breaking the record that had eluded him two years earlier. Krolewicz claimed the early lead but could not create much of a gap ahead of the other front-runners and settled back with the others.

Cantrell reported, “It was the favorite, Tom Zimmerman, who made the move. Apparently satisfied with his study of the competition, he set out to see who was ready to play hardball. As Zimmerman powered effortless away, the tight pack strung out in a line.” Others tried to catch him, but by mile 20 Zimmerman was ahead alone, passing the halfway mark in 2:01:06.

Heading toward the finish, he powered through the Walls and overcame the final 10 km of hot road without shade. “The merciless sun bore down on him. Scorching, searing heat blasted him from the road. Something gave. Then it gave a little more. Next thing, this awesome machine that had whipped over meatgrinder hills like so many highway overpasses was struggling along at eight-minute miles.” But he did it! He finished with a new course record of 4:15:22.

Charlie Trayer: The Next Record Holder

Episode 52 covered the running career of Charlie Trayer, of Reading, Pennsylvania, who was one of the greatest “short-range” American ultrarunners of the 1980s. In 1988, he brought his go-for-broke speed to Strolling Jim and was the pre-race favorite, even over the defending champ and course record-holder Zimmerman. The two dueled hard, but Zimmerman’s experience with the course, especially through “the Walls” helped him cruise to the win for the second year in a row with 4:16:45.

Episode 52 covered the running career of Charlie Trayer, of Reading, Pennsylvania, who was one of the greatest “short-range” American ultrarunners of the 1980s. In 1988, he brought his go-for-broke speed to Strolling Jim and was the pre-race favorite, even over the defending champ and course record-holder Zimmerman. The two dueled hard, but Zimmerman’s experience with the course, especially through “the Walls” helped him cruise to the win for the second year in a row with 4:16:45.

Trayer returned to Strolling Jim the next year, 1989, even more determined. Zimmerman could not defend his title because of a stress fracture, so Trayer was the clear favorite. He charged to the front as usual. “Sparks flew from Charlie’s feet as he continued to scorch the road.” He reached 10 miles in 57:20. But by 17 miles Steve Warshawer passed him, starting a classic battle, running sub-six-minute miles.

At mile 22, Trayer went back in the lead. Warshawer closed the lead to 40 seconds at the “Walls.” The race was decided on the most brutal section of the course. Twice Trayer surged, and twice Warshawer responded. Cantrell wrote, “Charlie’s trademark is a hard-working style and a seeming imperiousness to pain. He threw himself into the walls at a furious pace.” Trayer pulled away and set a new course record by only one second in 4:15:27.

Sean Crom Lowers the Record Further

Trayer returned in 1990, determined to defend his title. But also there, was Sean Crom, (1956-), a civil engineer from Reno, Nevada. Crom was the reigning “ultrarunner of the year” with wins also at the Leadville 100 and American River 50.

Trayer and Warshawer dogged Crom’s steps the entire way at Strolling Jim, but Crom opened gaps on the hills and pushed ahead of record pace. He said, “I ended up going out really fast and I was surprised no one came with me. I ran a comfortable place.” Cantrell reported, “Crom’s lead had mushroomed to seven minutes and suddenly he was nearly uncatchable. He pushed one of America’s fastest ultra course records even further into the realm of ‘unreachable.’” His new course record time was 4:12:17.

Andy Jones

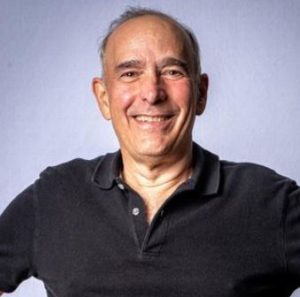

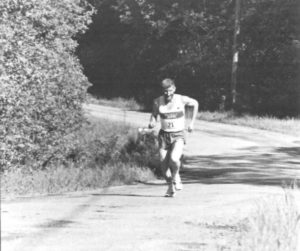

Andy Jones, was from Ottawa Canada (now from Cincinnati, Ohio) and became the most famous runner in the lore of Strolling Jim. During the 1980s he traveled the US and all over the world competing in marathons. His personal best was 2:17 at the 1985 Chicago Marathon.

Andy Jones, was from Ottawa Canada (now from Cincinnati, Ohio) and became the most famous runner in the lore of Strolling Jim. During the 1980s he traveled the US and all over the world competing in marathons. His personal best was 2:17 at the 1985 Chicago Marathon.

At age 28, in 1988, Jones, with only limited training on trails, burst on ultra scene, when he ran Ice Age 50 in Wisconsin. He hung with the overwhelming favorite, Tom Zimmerman, and then set a new Ice Age course record of 5:53. In 1990, Jones ran 50 miles in 4:54 at Golden Horseshoe 50 in Ontario, Canada, on a fast paved out-an-back course, just a few minutes off a World Record. At that time, it was the fourth fastest 50-miler ever ran.

1991 Strolling Jim Course Record for the Ages

In 1991, just a few days before Strolling Jim, Cantrell received a call from Jones confirming his entry into the classic ultra, in its 13th year. Cantrell was delighted, knowing that Jones had world-class speed. On race day, the weather turned out to be ideal for fast times, warm, cloudy, with a few short showers to cool the runners.

Jones took the lead from the start and after five miles in 28:20, he had already built up an astonishing four-minute lead, ahead of Crom’s early course record pace. He pulled away from the entire field and no runner ever had sight of him again. The leader vehicles were hard-pressed to stay in the lead as Jones looked very fresh passing through 15 miles.

Jones took the lead from the start and after five miles in 28:20, he had already built up an astonishing four-minute lead, ahead of Crom’s early course record pace. He pulled away from the entire field and no runner ever had sight of him again. The leader vehicles were hard-pressed to stay in the lead as Jones looked very fresh passing through 15 miles.

He hit the 20-mile mark in 1:54. Could the un-thinkable be accomplished at Strolling Jim, breaking the four-hour barrier? Jones later explained, “I realized at the halfway mark that I was having an extremely good day. I figured I ought to try for four hours since you never know when you’ll be ‘on’ like that again.” He cranked out the next five miles in less than 27:30. His marathon mark was 2:29. Four hours just might be possible.

Cantrell reported, “Andy screamed into the Walls. The Walls had not acquired their reputation by giving ground easily. But Andy Jones’s feet weren’t even touching the ground anymore.” He passed 35 miles in 3:22:51. With two miles to go he was clocking 5:40 miles, showing no sign of fatigue. Cantell was ecstatic, “A mixture of astonishment and exhilaration was at the finish, as race workers scrambled to prepare for Andy. It actually took a few minutes to convince folks we weren’t joking. Andy was coming home strong.”

Cantrell reported, “Andy screamed into the Walls. The Walls had not acquired their reputation by giving ground easily. But Andy Jones’s feet weren’t even touching the ground anymore.” He passed 35 miles in 3:22:51. With two miles to go he was clocking 5:40 miles, showing no sign of fatigue. Cantell was ecstatic, “A mixture of astonishment and exhilaration was at the finish, as race workers scrambled to prepare for Andy. It actually took a few minutes to convince folks we weren’t joking. Andy was coming home strong.”

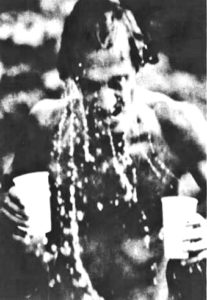

Jones crossed the finish line in 3:59:26. He smashed Crom’s “unreachable” course record by about 12 minutes and broke the four-hour barrier. “A smile burst across Andy’s face, the first change in his expression for the duration of the run. He had done the impossible. Then he leaned over and got sick, perhaps just to convince us he was a human. Strolling Jim saw not just a course record, but a redefinition of the race, as Andy Jones put in a run that ranks with the greatest performances of all time.”

Jones’ Later Running Career

Jones went on later that year to set a North American 100 km record of 6:33 on a slow surface course of grass, shell, gravel and cattle guards on a levee that ran on the east bank of the Mississippi River. You would think that Jones would have continued running ultramarathon distances with that dominant speed and endurance, but he went back to running marathons and was very busy achieving his Ph.D in Chemical Engineering. In 1997, he again stepped up to running ultras and won Sunmart 50 km on trails in Texas, beating a large field of 472 finishers. In 1997 he went and ran Olander Park 24 Hour race and broke the Canadian 12-hours and 100-miles record with 99.25 miles and 12:05. Both were also North American Records. In 1998 Andy ran the Ice Age 50 in 5:54 which set the course record there and stood for 25 years. His last ultra results were that year.

Jones went on later that year to set a North American 100 km record of 6:33 on a slow surface course of grass, shell, gravel and cattle guards on a levee that ran on the east bank of the Mississippi River. You would think that Jones would have continued running ultramarathon distances with that dominant speed and endurance, but he went back to running marathons and was very busy achieving his Ph.D in Chemical Engineering. In 1997, he again stepped up to running ultras and won Sunmart 50 km on trails in Texas, beating a large field of 472 finishers. In 1997 he went and ran Olander Park 24 Hour race and broke the Canadian 12-hours and 100-miles record with 99.25 miles and 12:05. Both were also North American Records. In 1998 Andy ran the Ice Age 50 in 5:54 which set the course record there and stood for 25 years. His last ultra results were that year.

After that Jones went back to run occasional marathons. The last marathon result found for him was in 2007, when he ran a 2:47 at the Cincinnati Marathon at the age of 46. One can only wonder what he could have done if he would have continued running 100-miles in his prime and tried racing mountain trail 100s.

The Strolling Jim Record Lives On

For the next three decades, Jones’ Strolling Jim Record stood untouched and seemed to be a record for the ages. It was viewed as one of the strongest ultrarunning course records ever. Many tried, but never came close. Hoping to attract elite runners, starting in 2015, Cantrell started to offer a $1,000 cash award for any runner who would break Jones’ course record. Scott Breeden, of Bloomington, Indiana, finished that year in 4:14:30, the fastest time since Jones’ record in 1991. Cantrell announced that he would keep adding money to the award pool until the record was broken.

For the next three decades, Jones’ Strolling Jim Record stood untouched and seemed to be a record for the ages. It was viewed as one of the strongest ultrarunning course records ever. Many tried, but never came close. Hoping to attract elite runners, starting in 2015, Cantrell started to offer a $1,000 cash award for any runner who would break Jones’ course record. Scott Breeden, of Bloomington, Indiana, finished that year in 4:14:30, the fastest time since Jones’ record in 1991. Cantrell announced that he would keep adding money to the award pool until the record was broken.

Zach Beavin

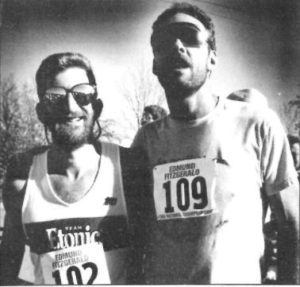

In 2019, Zack Beavin, age 24, from Lexington, Kentucky came close, running the second fastest Strolling Jim 40 ever, with a time of 4:07:42. Beavin was an elite marathoner, with a PR of 2:18:26, who competed at the 2020 Olympic Marathon Trials. He graduated from the University of Kentucky with a degree in Mechanical Engineering and an MBA, but quit his first job as an engineer after just four days and went back to working in a running store.

In 2019, Zack Beavin, age 24, from Lexington, Kentucky came close, running the second fastest Strolling Jim 40 ever, with a time of 4:07:42. Beavin was an elite marathoner, with a PR of 2:18:26, who competed at the 2020 Olympic Marathon Trials. He graduated from the University of Kentucky with a degree in Mechanical Engineering and an MBA, but quit his first job as an engineer after just four days and went back to working in a running store.

Beavin started running at a very early age and had always wanted to run ultras too after reading about the Comrades Marathon (54 miles) held in South Africa when he was in sixth grade. He ran a half marathon at the age of 11 with a time of 1:31. He was a very talented miler and two-milers in high school where his team won state championships. He then ran in the SEC for the University of Kentucky in cross country and track.

Beavin started running at a very early age and had always wanted to run ultras too after reading about the Comrades Marathon (54 miles) held in South Africa when he was in sixth grade. He ran a half marathon at the age of 11 with a time of 1:31. He was a very talented miler and two-milers in high school where his team won state championships. He then ran in the SEC for the University of Kentucky in cross country and track.

Out of college, he started running marathons and ran 2:18 in his 4th try. One summer, on a family vacation to watch the Olympic Trials in Eugene, Oregon, on the way he ran 31 miles around Crater Lake, the first time running that distance and came away injured.

Strolling Jim in 2019, was his first race longer than 50 km and his first road ultra. Looking back on his first Strolling Jim 40, he felt that he lacked the specific fitness to run sub-4-hours and was “toast” after 50 km. He committed himself to tune his training to the 41.2 miles and hilly roads. His prime focus was to break the record.

Strolling Jim in 2019, was his first race longer than 50 km and his first road ultra. Looking back on his first Strolling Jim 40, he felt that he lacked the specific fitness to run sub-4-hours and was “toast” after 50 km. He committed himself to tune his training to the 41.2 miles and hilly roads. His prime focus was to break the record.

2020 was the year of the pandemic, only 30 runners ran Strolling Jim, and Beavin was not in the field because he was taking time off after running in the Olympic Marathon Trials. He set his sights to break the record in 2021. He did add multiple 20-30-mile runs per week into his training.

In November 2020, he impressed the ultrarunning sport by crushing the Tunnel Hill 50 course record with a time of 5:03:05, the fourth fastest American 50-mile time ever. (Jim Walmsley held the American best of 4:50:08, set in 2019). Beavin recovered quickly and focused on getting ready for the 2021 Strolling Jim. Leading up to the race, on social media, Andy Jones, the record holder, gave him advice.

Zack Beavin Goes After the Record

The historic race was held on May 1, 2021. Beavin brought to Strolling Jim his experienced friends who crewed him at Tunnel Hill. He recalled, “Heading to the start line, I was weirdly nervous. I made a point to calm myself. I was fit and knew I had done the work to run well.” The weather was ideal with a cool, calm sunny day, with the high temperature in the low 70s.

The historic race was held on May 1, 2021. Beavin brought to Strolling Jim his experienced friends who crewed him at Tunnel Hill. He recalled, “Heading to the start line, I was weirdly nervous. I made a point to calm myself. I was fit and knew I had done the work to run well.” The weather was ideal with a cool, calm sunny day, with the high temperature in the low 70s.

Beavin, dressed in bright salmon-colored shorts and shoes, took the lead from the start and focused on keeping a pace that would hold him for the duration of race. Finding a rhythm at Strolling Jim was difficult because of the constant climbing and descending. He flew through the five-mile mark in 28:30. With his 2019 experience on the course he knew when and how to adapt to the hills. He wrote, “When I pressed on the gas just a little on some of the smaller climbs, I noticed that my marathon instincts started to come out. I would start to press just a little and a bit of rhythm started to enter my stride.”

Beavin, dressed in bright salmon-colored shorts and shoes, took the lead from the start and focused on keeping a pace that would hold him for the duration of race. Finding a rhythm at Strolling Jim was difficult because of the constant climbing and descending. He flew through the five-mile mark in 28:30. With his 2019 experience on the course he knew when and how to adapt to the hills. He wrote, “When I pressed on the gas just a little on some of the smaller climbs, I noticed that my marathon instincts started to come out. I would start to press just a little and a bit of rhythm started to enter my stride.”

Beavin swapped fluid bottles with his crew every few miles and reached the 15-mile mark at 1:25:56. His legs felt heavy and he slogged along, not feeling uncomfortable, but lacking in confident strength. He still had more than 25 miles to go, and doubts started to enter his mind. But he attacked the course one mile at a time and his pace continued go as planned as he arrived a mile 20 in 1:53:51, a few seconds ahead of Jones’ record pace.

Beavin swapped fluid bottles with his crew every few miles and reached the 15-mile mark at 1:25:56. His legs felt heavy and he slogged along, not feeling uncomfortable, but lacking in confident strength. He still had more than 25 miles to go, and doubts started to enter his mind. But he attacked the course one mile at a time and his pace continued go as planned as he arrived a mile 20 in 1:53:51, a few seconds ahead of Jones’ record pace.

Cantrell observed, “It was a privilege to get to watch Zack assault the course. Every runner has their own style. Thirty years ago, Andy sliced through the air like an arrow, his feet seemed to barely touch the ground, and he went up the hills like they were not even there. Zack attacked the course from the gun and kept up the assault with the tenacity of a bulldog. His style reminded me of Charlie Trayer or Tom Zimmerman.”

Cantrell observed, “It was a privilege to get to watch Zack assault the course. Every runner has their own style. Thirty years ago, Andy sliced through the air like an arrow, his feet seemed to barely touch the ground, and he went up the hills like they were not even there. Zack attacked the course from the gun and kept up the assault with the tenacity of a bulldog. His style reminded me of Charlie Trayer or Tom Zimmerman.”

Beavin found a groove and was ahead of record pace at the half-way point and felt invincible at mile 25. He hit the marathon mark in 2:28 which was a new Strolling Jim marathon split record. He recalled, “When I made the turn into the infamous ‘Walls,’ I knew I was in a much better spot than I was in 2019. I swapped my bottle with my crew again and drew some energy from their cheers. I was still feeling strong enough to aggressively attack this brutal section of the course. As I attacked one hill after another, I was shocked and surprised at how well my pace was holding up.” He reached the 50 km mark about a minute faster than Jones’ record pace with ten miles to go.

In 2019 Beavin’s pace floundered after 50 km, but it didn’t falter this time and he held a pace just under six-minute-miles. Cantrell wrote, “The ‘Walls” make or break racers. When Zack went through the 50 km split (2:56) you could see he was hurting, but he did not let up the intensity one bit.”

In 2019 Beavin’s pace floundered after 50 km, but it didn’t falter this time and he held a pace just under six-minute-miles. Cantrell wrote, “The ‘Walls” make or break racers. When Zack went through the 50 km split (2:56) you could see he was hurting, but he did not let up the intensity one bit.”

His crew screamed encouragement at the 35-mile mark. He made his last bottle swap at mile 39. He knew that the record would be his as he continued to run at six-minute pace. He wrote, “The tenths of a mile clicked past agonizingly slowly, and I focused on a building off in the distance that I thought marked the finish line.”

With 200 meters to go, Beavin found new life in his legs and let out a jubilant fist pump as he crossed the finish line in 3:55:44, breaking the 30-year Strolling Jim record by nearly four minutes. A kind bystander caught him and guided him to a chair. Beavin wrote, “He made sure my Jello legs safely found the seat because at this point they were basically useless. He was wearing a grey ‘sub 4’ Strolling Jim shirt, put a medal on me, and as soon as I had my wits about me, introduced himself as Andy Jones. I had obsessed over this record for years and just raced the ghost of this man for four hours, and here he was to congratulate me on breaking his unbreakable course record. It was a special moment.”

Cantrell summed up the historic 2021 record. “Maybe he was only competing with Andy’s ghost, but there was no missing the competitive fire that burned in his heart. I have been lucky enough to see a lot of great performances by a lot of great ultrarunners at a variety of events. This was among the very best.” Beavin next had his sights on winning the 2021 JFK 50 .

Cantrell summed up the historic 2021 record. “Maybe he was only competing with Andy’s ghost, but there was no missing the competitive fire that burned in his heart. I have been lucky enough to see a lot of great performances by a lot of great ultrarunners at a variety of events. This was among the very best.” Beavin next had his sights on winning the 2021 JFK 50 .

The classic Strolling Jim 40 had been conquered once more. Who will be the next?

Sources:

- Strolling Jim 40 Mile Run on Realendurance.com

- Strolling Jim results on arrs.run

- Nick Marshall, Ultra Distance Summary, 1979-1985

- The Tennessean (Nashville, Tennessee), May 4, 6, 1979, Apr 30, 1982, May 6, 1990, Apr 30, 1991

- Alabama Journal (Montgomery, Alabama), Apr 10, 1984

- Pensacola News Journal (Florida), Jun 18, 1982

- Ultrarunning Magazine, June 1981, July/August 1982-1991

- TrailRunning, “Laz Lake’s formula for gender differences in ultrarunning”

- Strolling Jim 40 – Course Record, 5:43 pace for 41+ Miles

- Laz Lake, Ultralist comment, Mar 2, 2021

- Run Your Mouth Podcast, “Antelope Children with Zack Beavin”

- The Adventure Jogger Podcast, “Zack Beavin: Strolling into Wartrace”