Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 25:25 — 29.6MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

Watching sports on Christmas Day is enjoyed by millions of sporting fans. But it also is probably despised by even more of those sporting fans’ families who have other priorities on that special day. While today the events watched are primarily basketball and football, back 144 years ago in 1879, the most popular sport taking place in America on Christmas Day was ultra-distance running, called Pedestrianism. Why would thousands leave their festive holiday celebrations to go many miles by horse carriage to smoke-filled arenas to watch skinny guys walk and run in circles for hours?

In America, on Christmas Day, the NBA basketball games have become a tradition (more than 75 years) and increasingly NFL football games are being played. What about soccer (football) in Europe? The most famous Christmas Day game took place during World War I in 1914 between British and German soldiers in No Man’s Land in Flanders, Belgium. Soccer leagues played on Christmas well into the 1980s before they stopped.

Back in 1879, the featured Christmas Day sports event was ultrarunning/pedestrianism. That day, at least four ultramarathons were taking place. The largest six-day race in history, “The Rose Belt.” with 65 starters, held in Madison Square Garden in New York City, in front of thousands of spectators. In Chicago, at McCormick Hall, four pedestrians were competing in another six-day race, more crowded facilities. Probably the most unusual ultramarathon in history was also taking place in the Red Sea aboard the steamer “Duke of Devonshire.”

Pedestrianism and Six-Day Races

A British long-distance walker, Foster Powell (1734-1793) started a focus on walking/running for six days and is recognized as the “Father of the Six-Day Race.” In 1773, Powell caused a great stir when he walked and ran about 400 miles from London to York and back in less than six days. “Walking” in those very early days was a general term. These pioneer ultrarunners of the late 1700s and early 1800s actually performed a “jog-trot,” or a mixture of walking and running. There was no emphasis yet on “fair heel-toe” walking.

Powell established a six-day standard that would be remembered for decades. Nearly all six-day attempts in the decades that followed pointed their efforts to Powell’s previous accomplishments. Dozens attempted to match or improve on his feat. By 1779, Powell was the first long-distance runner who was referred to as a “pedestrian” performing the art of “pedestrianism.” That term took hold in England and eventually referenced competitions on foot for all distances, even sprints.

Pedestrianism came into the American public eye as Edward Payson Weston (1839-1929) of Providence, Rhode Island, made several attempts in 1874 to walk 500 miles in six days. P. T. Barnum (1810-1891), of circus fame, had the brilliant idea to move such attempts indoors for vast audiences to watch, in his massive Hippodrome in New York City. In 1875, Barnum put on the first six-day race in history, won by Weston with 431 miles. In these races, the winner was the athlete who reached the furthest distance within six days.

By 1879, this unique indoor spectator reality show had exploded in popularity in America and spread to England. By the end of the year, more than 125 such races had been held since 1875, involving at least 1,000 starters, both men and women, in front of more than a million spectators. The British introduced race rules called, “go-as-you-please” which allowed running in addition to walking, helping the Brits to catch up to the Americans who had been dominating the ultra-distance strict heel-toe walking sport.

Six-Day Race on the Red Sea

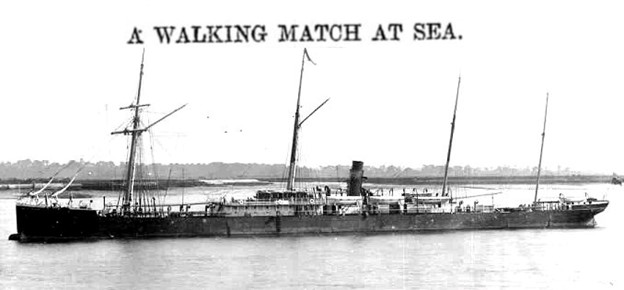

The Duke of Devonshire was described as “the favorite passenger steamer, 3,100 tons, and with 400 horsepower. “She has most superior accommodations for saloon passengers and is fitted with bathrooms and all necessaries for the Indian voyage. Carries a surgeon and stewardess.” The ship was operated by the Ducal Line and captained by W. Turner.

In 1879, the steamer had been making trips back and forth between London and Calcutta, India, or Ceylon (Sri Lanka), using the Suez Canal that was opened in 1869. It had arrived in London on December 16th, from Calcutta and immediately turned around to head for Ceylon. While on the Red Sea, during the Christmas week, Captain Turner laid down a walking course on the deck from the bow ladder to the stern and back. The ship was about 380 feet long, so the course was probably about 8 laps to a mile.

“With a view of encouraging exercise among the gentlemen passengers,” fourteen men started a six-day walking race, probably six hours per day, on Dec 22, 1879, paying a fee of 2 shillings, 6 pence ($20 today). All went well on day one with Mr. Marshall of Ceylon leading with 35 miles to Mr. Wheatley of Calcutta with 26 miles. But “these enthusiasts rapidly felt the effects of deck walking in the shape of heavy blisters and stiffness.”

Walking for hours out in the elements must have been very challenging. The steamer cruised at a top speed of about 20 m.p.h. which would have created a stiff cool breeze with a constant surging up and down with the waves.

By day six, only two remained and were finally convinced to stop. Mr. Goodwin of Ceylon won by two miles with 149.5 miles over J. Wier of Cachar, India, with 147.5 miles. Goodwin was carried up and down the deck while Mr. Trotman, a great musician, who played on the violin, “See the Conquering Hero Comes.” At a post-race dinner, Captain Turner issued toasts first to “her Majesty the Queen,” and then to “The victor of the walking match.”

Another Walking Match on a Ship

In October, 1901, another walking match was held on the steamer, the Coptic going from China to San Francisco, California. The ship, built in 1888, was “Sixteen of the passengers entered the contest. The deck was measured and from 6 ‘oclock in the morning until 6 o’clock in the evening the contenstants walked, encouraged by the plaudits of more sedentary passengers, who drew up their deck chairs close to the space alloted tothe walkers and watched.” The race was for five days and won by Lieutenant Heinrich of the German army with 128 miles. A. J. Flahrety of Pekin Consular Cadets was second with 116 miles.

Six Day Race on Christmas in Chicago

The race was put together at the Chicago Field newspaper office between Crossland and Guyon, with a $200 prize plus a percentage of gate money. The race was open to all, but only two others entered. Pierce, who at first was a mystery entry, entered as the “dark horse,” and known to be “a full-blooded African.” His identity was to be kept a secret until the race and some thought he was the famed pedestrian, Frank Hart (1856-1908). Crossland, at first, objected to having a black man compete, but later consented.

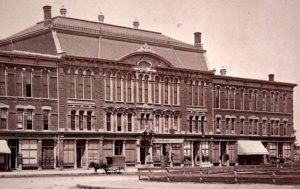

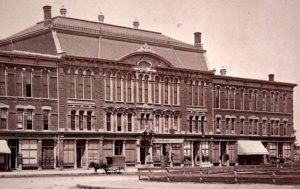

McCormick Hall was the first large music hall opened after the Chicago fire of 1871. Located on the corner of Kinzie and North Clark Street, it opened in 1873. By 1879, it was referred to as “the deserted stronghold of singing societies.” The main room was only 100×120 feet. The track constructed for the race was tiny, 22 laps to the mile, covered with sawdust and was six feet wide. “The scoring will be by dials, a system which proved immensely popular during recent Eastern matches.”

A large crowd came and filled the hall to watch the plodders around the track. Guyon had gone into the lead over Dobler on Christmas Eve. “Guyon’s trot gives him an advantage, and he loses no opportunity to make the best of it.” Guyon held the lead on Christmas, “regulating his pace somewhat by that of the stockyards man, and managing to keep ahead of him all the time. Both men were in excellent condition and indulged in frequent spurts of running. But Dobler could not overtake the plucky Canadian, who adopted for the greater portion of the day, the jog-trot so successfully used by Charles Rowell in his contest for the Astley belt.” At the end of Christmas Day, Guyon had 258 miles, Dobler 237, Crossland 204, and Pierce 193. It was noted the interest in the race was gradually decreasing.

Guyon went on to win the race on December 27, 1879, with 331 miles to Dobler’s 325 miles. Crossland reached 280 miles and Pierce recorded 259 miles. Overall, the race was not a financial success because the paying spectators were not consistently large.

Four-Day Race at Natick, Massachusetts

At the Concert Hall in Natick, Massachusetts, a four-day, five-hours each day race began on Christmas Eve at 6:30 p.m. “The hall was crowded. Music was furnished by the Hibernian Brass Band.” There were 14 starters. The race continued on Christmas Day as P. Welsh, of Ashland, Massachusetts, held his lead. He reached 96 miles on day three (15 hours). But James T. Burnes, of Southville, Massachusetts, won the next day with 127 miles, coming in “lame” with terrible blisters. Eight of the Fourteen starters finished.

At nearby Boston, on Christmas Day, the Boston Athletic Club put on a series of shorter races at the “Siege of Paris” building and attracted sizeable audiences. The main race was a three-hour “go-as-you-please” race won by M. Curtin, with 22 miles, 1 lap, followed by J. H. Maxwell, with 21 miles, 13 laps, and J. T. Newcomb, with 21 miles, 7 laps, 1 lap. Other races included a ten-mile run, and various track and field contests.

Six-Day Rose Belt Race in Madison Square Garden

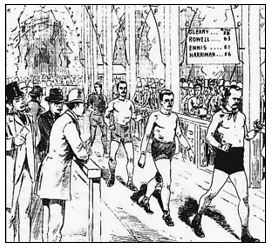

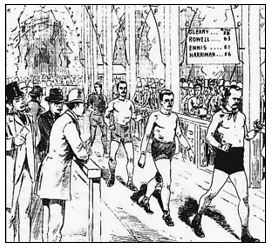

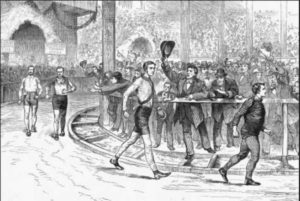

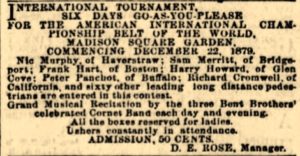

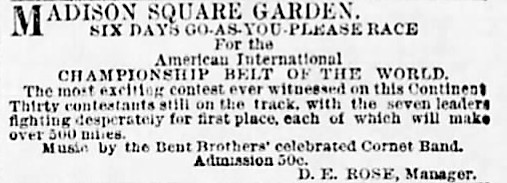

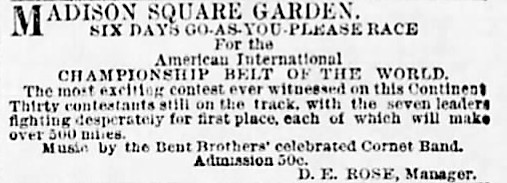

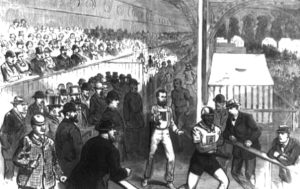

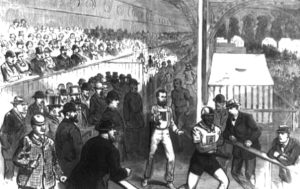

The big-time 1879 Christmas week race was held in Madison Square Garden in New York City. The original Garden stood on the block that now contains the New York Life Building. For the Christmas week, it became the site of the “Great International Six-Day Race” or “Rose Belt.” The manager of the race was Daniel Eugene Rose (1846-1927) of New York City, a pedestrian promoter and owner of the D. E. Rose cigarette manufacturing company. This was the largest known six-day race in history with 65 starters.

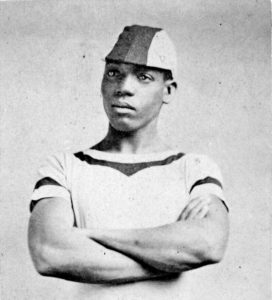

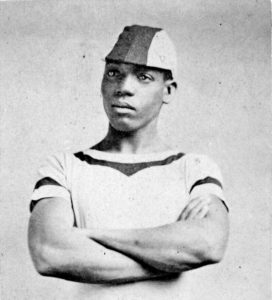

The most well-known pedestrian in the field was Frank Hart (1856-1908), the famous black runner from Boston, Massachusettes, born in Haiti, who won the Silver Belt with 362 miles. His best six-days distance to that point was 482 miles. He is the subject of Davy Crockett’s book, Frank Hart: The First Black Ultrarunning Star. Stephen Brodie (1861-1901), the young newsboy also got a lot of attention, along with Peter J. Panchot (1841-1917), of Buffalo, New York, the winner of the American Championship Belt in April with 480 miles. Nicholas Murphy (1861-1904) of Haverstraw, New York, had previously gone the furthest in six days with his 505 miles, winning the First O’Leary Belt.

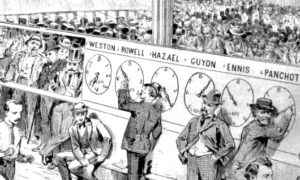

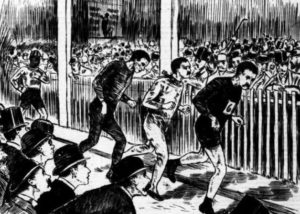

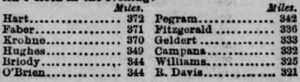

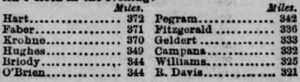

After the first day, December 22, 1879, Panchot led with 120 miles and Hart was in second place with 117 miles. On day two, there were more surprises as other leading contenders quit. The first day leader, and heavy favorite, Panchot quit, leaving Hart to secure the lead with 208 miles after day two, for a 48-hour American record. Only 48 of the 65 starters remained in the race.

On Christmas Eve, the race continued. Outside the Garden, in the city, the streets were very crowded. “There were many shoppers abroad in cabs and carriages, and the livery stable keepers found it difficult to meet the demands made upon them. The cars and stages and the ferryboats were thronged with passengers who carried brown paper parcels, large and small. Nobody had time to stop to think or talk about the mud in the streets.”

Inside the Garden, Hart lost the lead in the evening, in front of 2,000 spectators, to Christian Faber (1848-1908), of Newark, New Jersey, when he went to get some sleep. Grumbles were heard by those with wagers on Hart, worried that he would not return. But Hart had not had very much sleep and needed it badly. The crowd seemed to be getting bored, cheering rudely “with chaffing, in boisterous tones, to one another and the pedestrians by turns.” Hart returned at midnight to kick off day four and Santa was delivering gifts in the city. Faber had 294 miles and Hart was at 291 miles after three days. Ten more runners chose to quit and celebrate their Christmas away from the Garden.

![]()

![]()

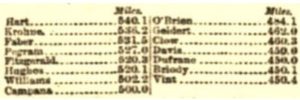

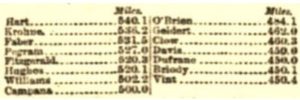

“The race continued with renewed excitement. Hart looked the most wearied, and all his friends began to lose hope.” He was in third place, but only two miles behind the leader. At 9 p.m., Hart, in his familiar striped suit, finally retook first place, which caused the crowd to cheer. Hart’s new trainer, Happy Jack Smith, was pleased with his runner and said he was in “tip-top condition, determined to do or die.” His goal was to exceed 530 miles during the race.

There was a tragic consequence of the Christmas week race. One of the contestants, Clarence G. Howard (1859-1879) who had withdrawn from the race on the first day after 75 miles, feeling sick, died four days later at his home on Long Island. “Everything possible was done to save him, but without avail, and he died from utter exhaustion. He was more like a schoolteacher or a man of sedentary employment than a professional walker.”

As New Year’s Day approached, three more six-day races began in Kansas City, Missouri, San Francisco, California, and Aberdeen, Scotland involving a total of 48 runners. None of them came close to matching Hart’s 540 miles.

Sources:

- Chicago Daily Telegraph (Illinois), Dec 14, 20, 22, 23, 27, 1879

- Chicago Tribune (Illinois), Dec 15, 23, 28, 1879

- The Inter Ocean (Chicago, Illinois), Dec 23, 26, 1879

- Evening Sentinel (Staffordshire, England), Dec 26, 1879

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Dec 25,26, 27, 28, 1879

- The Times (London, England), Oct 3, 1879

- The Leeds Mercury (England), Dec 5, 1879

- New York Daily Herald (New York), Dec 22, 25, 26, 28, 30, 1879

- New York Tribune (New York), Dec 23, 1879

- The New York Times (New York), Dec 26, 1879

- BBC, “The sports games that don’t stop for Christmas Day”