Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 28:42 — 34.7MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

You can read, listen, or watch

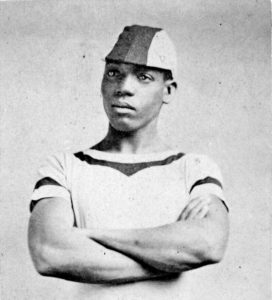

In 1879, just twelve years after the Civil War ended, Frank Hart of Boston, Massachusetts, became the first black running superstar in history, and the most famous black athlete in America. In a sense, he was the Jackie Robinson of the sport of ultrarunning in the 19th century, overcoming racial barriers to compete at the highest level in the world, in the extremely popular spectator sport of ultrarunning/pedestrianism.

Frank Hart’s full story has never been told before. It is an important story to understand, both for the amazing early inclusiveness of the sport, and to understand the cruel racist challenges he and others faced as they tried to compete with fairness and earn the respect of thousands. He was the first black ultrarunner to compete and win against whites in high-profile, mega-mile races.

This biography also presents twenty-three years (1879-1902) of the amazing pedestrian era history as experienced by Hart when ultradistance running was the most popular spectator sport in the country. He competed in at least 110 ultras, including eleven in Madison Square Garden, where he set a world record, running 565 miles in six days in front of tens of thousands of spectators and wagerers. During his running career, he won the equivalent of $3.5 million in today’s value.

NOTE: This tale must be viewed through the historic lens of nearly 150 years in the past. It will present news article quotes using the words and labels used in that era, that today are now universally viewed as racist, heartless, and offensive. But by stepping back in time, one can appreciate the courage and determination that Frank Hart experienced in a world that at times tried to work against him. Items in quotations are taken directly from newspaper articles of the era. Also note, this multi-part series is an abridgement of the book, Frank Hart: The First Black Ultrarunning Star.

Frank H. Hart (1856-1908) was believed to have been born in Haiti, in 1856. He said his given name was Fred E. Hichborn, although on several legal documents in the years before he started running, and throughout his life, he stated his name was Frank Hart. He said that his parents were Joseph Hart and Elizabeth (Mallory) Hart. It is likely that the Harts adopted him. “Frank Hart” was not just a stage name.

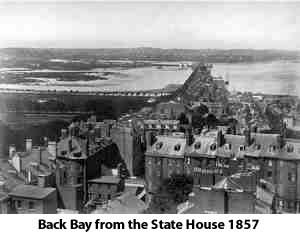

Hart’s family immigrated to the west end of Boston, Massachusetts in 1866, after the Civil War ended, while Hart was a boy of about ten years. Why Boston? Haiti had been experiencing political turmoil and revolts for several years. The West End of Boston at that time was one of the few areas of the country where blacks were allowed to have a political voice. In the years following the civil war, many blacks from the South migrated to Boston. More than 60% of Boston’s black population lived in the West End. It would be the future home of the Museum of African American History. As a young man in Boston, during the 1870s, Hart worked as a grocery clerk, teamster, fireman and did “general jobbing,” developing into a talented athlete, and became an American citizen in 1878. He competed as an amateur in single sculling rowing competitions at Silver Lake in Tewksbury, Massachusetts, where he demonstrated “remarkable staying qualities as an oarsman.”

Pedestrianism became popular in black communities. In April 1876, John Briscow called “the colored pedestrian” attempted a 50-hour walk without sleep or rest in a billiard saloon, in Washington D.C. He swelled up and had to quit six hours short. In March 1879, a 25-hour race was conducted in Baltimore, Maryland, for all the “colored pedestrians” in the area. Black pedestrians competing against whites was still a rare occurrence.

Hart Enters the Sport, Crossing the Racial Barrier

Hart married at age 19, on September 23, 1875, in Boston to Mary Augusta Berry (1855-1898), who had been born in Norfolk, Virginia. Mary gave birth to two children. Their son, Francis “Frank” S. Hart was born on April 14, 1876. Sarah Maynard Hart (1878-1880) was born April 27, 1878.

In 1879, Hart jumped into the pedestrian sport with only a little serious training in a quest to earn more money. He said, “I don’t really know how I became a pedestrian. I think I caught the infection in the air, like some others. I heard a good deal about walking and when I came to try, I found I could walk too. So, liking it, I kept on it and continued to exercise. I found it did not fatigue me and I went right ahead but knew nothing about training myself or what was necessary to preserve my condition.”

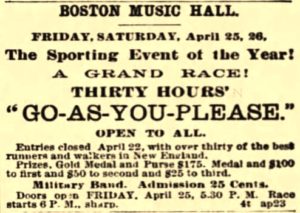

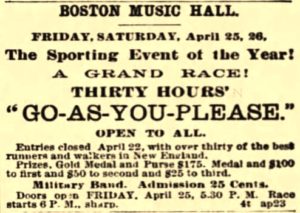

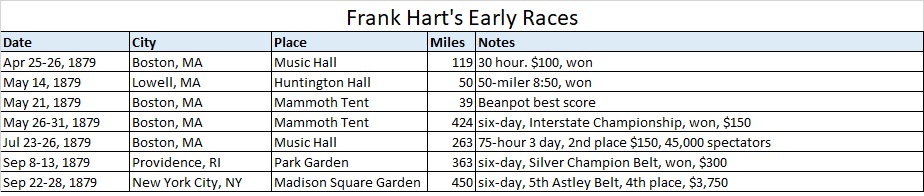

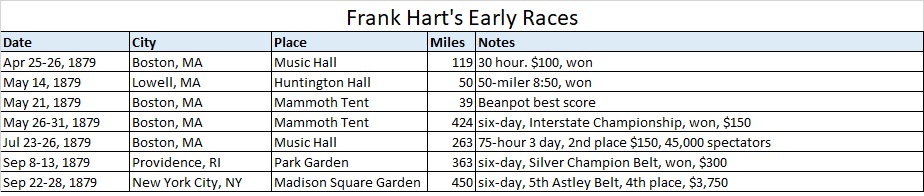

Hart did have some help and was “thoroughly drilled, trained, and tested to the satisfaction of those interested” before he entered his first race. His first race was held on April 25-26, 1879. It was a 30-hour go-as-you-please (running or walking permitted) competition held at the Music Hall in Boston, with a prize of $100 going to the winner. The race was open to all and was put on by Fred J. Englehardt of Boston, the editor of Frank Leslie’s Sporting Times. The local sportsmen wanted to find runners to represent the state in an upcoming multi-state long-distance running competition.

Englehardt did not know Hart was a black man until he saw him at the start. When Englehardt announced the starters, some of the other competitors objected to having a black man run in the race. Englehardt told them that Hart would run and if they did not like it, they could get out of the race. They all ran. Despite opposition, Hart and Englehardt can be credited for breaking the 19th-century color barrier in ultrarunning.

Englehardt made sure that neither race nor ethnicity would be a barrier in this historic ultra. “The large field included a colored aspirant, several Irishmen, an Indian, an Englishman, and several Yankees.” Hart said, “I never thought of anything, least of all my color, only wanting to walk.” He knew that he needed to win, or he would be back to selling groceries.

Forty men started at 6 p.m. on April 25, 1879. Hart certainly was not among the betting favorites, rather he was a curiosity, along with the “Canadian half-breed Indian,” Tayaguariel. The spectators were surprised when “the Indian” took the lead followed by Hart, who kept his eye on the leader and eventually passed him into the lead after about six hours and thirty-one miles. Some competitors and spectators tried to “play tricks” on Hart to get him mad and hopefully thrown out of the race. Englehardt caught a man trying to fling pepper in Hart’s eyes and the angry race director stepped in and decked the man to the ground. He then told everyone to leave Hart alone or else they would receive the same punishment.

Hart held onto the lead for hours. “Hichborn (Hart), is in fine order, being trained down to good condition, with clean limbs, without an ounce of superfluous flesh. He showed good speed and wind.” After 20 hours, he reached 90 miles and had a commanding lead. “The sight was novel and interesting as the varied-colored animated humanity went round and round the hall.” To the great surprise of the spectators, Hart won the race with 119 miles in 30 hours, winning the Englehardt Medal and the $100.

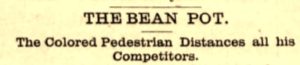

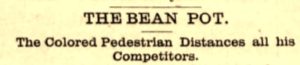

The Bean Pot Tramp

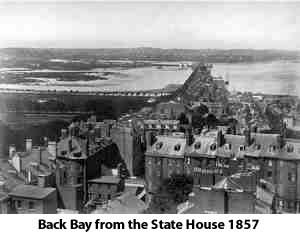

Hart earned a spot in the Interstate Beanpot competition, representing Massachusetts. This was a relay tournament between teams from Massachusetts, Maine, and Rhode Island, called, “The Bean Pot Tramp” held in a mammoth tent at the Riding Academy in Back Bay, Boston. Each state’s team consisted of twelve runners. Every day, for six days, two runners on each team ran for six hours each. Maine came out on top, but Hart ran the second furthest of all the runners, more than 39 miles, earning him the respect of the sport in New England.

For the final week of the tournament, Hart competed in a six-day walking match with twenty others. He put on an impressive performance. On day four, running in third place, he competed in an ad hoc sprint against Joseph E. Coughlin (1853-) of Warwick, Massachusetts. Coughlin tripped and fell on the track and made the accusation that Hart had intentionally tripped him. Hart insisted it was accidental. He was almost disqualified until Coughlin withdrew his protest.

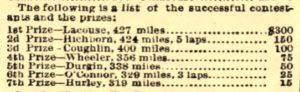

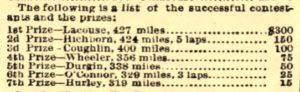

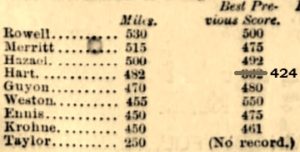

The last day turned into a fierce race between Richard Lacouse (1848-1923), and Hart. Both had spells where they collapsed on the track due to the intense heat inside the tent. Hart’s episode was serious. “Every effort was made to revive him, as he was only a few laps behind Lacouse, although it was thought for a time that he was dead, and after about an hour and a half of unceasing efforts, he revived sufficiently to warrant a removal to his house.” Lacouse ran only a few more laps when he also collapsed, but he held on for the win of 427 miles, to Hart’s 424. Hart won $150 and came away with a sprained knee.

Daniel O’Leary Starts Training Hart

On July 23-26, 1879, Hart placed an impressive second place at O’Leary’s six-day, 75-hour race held in Boston’s Music Hall, promoted by Engelhardt. That success got the attention of famous American pedestrian, Daniel O’Leary (1846-1933) of Chicago, who took Hart under his wing to train and back financially. O’Leary had faced discrimination as an Irish American. He had become a leading advocate of women in the sport and now became a supporter of Hart, helping him overcome racial prejudice against him. O’Leary spent a couple of months with Hart, “giving him information about walking and advancing his interests.” Soon Hart would be given the nickname “Black Dan” or “Young Dan” which was a huge compliment during that era — a black and younger version of the best early pedestrian, Daniel O’Leary.

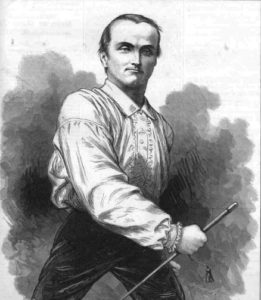

Plans were coming together for the 5th Astley Belt six-day race to be held in Madison Square Garden. The Astley Belt races were a series of world championship six-day races that had been established by Englishman Sir John Dugdale Astley (1828-1894) in early 1878.

Originally the 5th race in the series was supposed to be held in October 1879, but the British moved it up to September. Edward Payson Weston was the current holder of the Astley Belt and the six-day world record holder with 550 miles. O’Leary entered Hart in the race which was an “astonishment” to the manager of the race, Charles D. Hess (1838-1909), who thought the entry of the black runner “seemed strange” and should have been approved by the Astley managers in London. This was a major development, for a black runner to compete for the greatest prize in the sport, on the biggest stage at Madison Square Garden. There had been other black pedestrians in the sport before Hart, but none had yet competed at this level. On August 5, 1879, a cable with £100 was sent to Sporting Life in London to secure Hart’s entry.

The news went around the country that a “Boston negro” was going to compete. O’Leary seriously coached him to get ready for the race. Public relations were also important to get Hart in front of the public. He put on an eight-mile exhibition run as a warmup act before a featured 75-hour race at Allston Hall in Boston.

Providence, Rhode Island Race

Unwisely, two weeks before the Astley Belt race, on Sep 8-13, 1879, Hart competed in a six-day 12.5 hours per day race at Providence, Rhode Island in Park Garden put on by O’Leary. When he had originally entered this race, it was thought that the Astley Belt race would be held weeks later but then it was moved up. Hart won the Providence race easily with 362 miles, pleasing his friends, and proving that he was worthy to compete for the Astley Belt. It was pointed out that he beat eleven “white competitors.” He won $300, a gold chain, and a solid silver belt and then rested until the next race.

Pedestrians Protest Again Hart

Five days before the Fifth Astley Belt Race, a pre-race meeting was held in New York City, at the office of Turf, Field, and Farm, attended by Hart. The first agenda item was whether Hart, a “colored ped” should be allowed to run. “Objections were made on account of Hart’s color, and a letter of protest from Edward Payson Weston had been presented. Weston argued that the white competitors ought not to be compelled to associate with a negro on the track.”

George W. Atkinson, of the Sporting Life in London, overseeing the race for John Astley said, “without hesitation” that Hart would not be excluded, and quoted race rules that stated any man could enter who deposited £100. One of the men present said, “Do you call that (n-word) a man?” Englehardt, Hart’s backer, spoke up and said, “You will find that Frank Hart is a pretty good man.” That cut off the racist discussion. Hart signed the race agreement and was given a round of applause. He stated that he had recovered from his six-day race the prior week and hoped it would not hurt his chances. Englehart said, “I hardly expect he will come in first, though there is no telling beforehand. I do expect, however, that he will get a good place.”

Fifth Astley Belt Race

The races for the Astley Belt were the most prestigious six-day races of the era. Daniel O’Leary of Chicago won the first two Astley Belt Races. Charles Rowell (1852-1902) of England, won the Third Astley Belt Race and brought the belt back to England. Edward Payson Weston won the fourth race and would defend the belt on September 22, 1879, in Madison Square Garden, New York City.

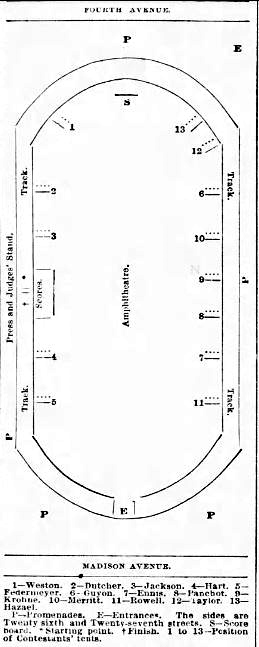

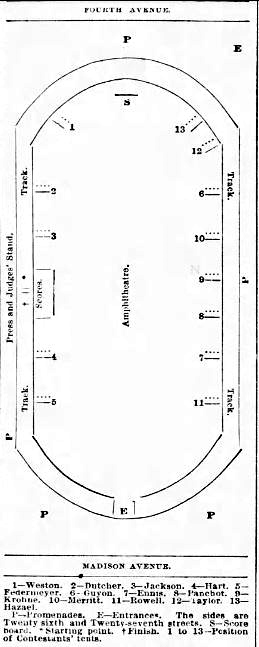

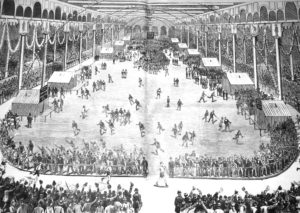

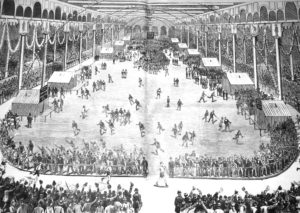

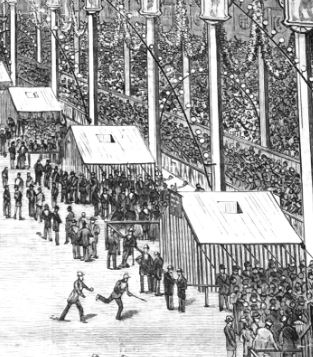

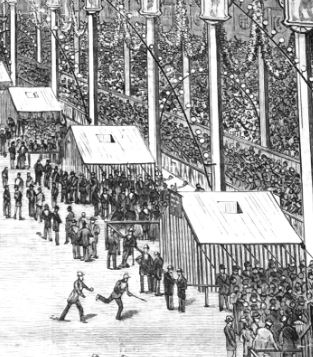

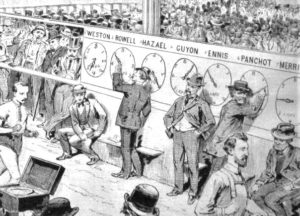

More than 250 men went to work preparing Madison Square Garden for the race. They constructed the track, built the stands, and put down new flooring. “The pedestrians will be accommodated in tents placed around the inside of the track. The stand for the scorers, judges, and reporters was built in three tiers.”

An Astley Belt pre-race description was published that included: “Frank Hart, the colored boy is a full-blooded Haitian negro. He is a round-faced, copper-colored, boyish-looking fellow, and looks uncomfortable in the good clothes that have been bought for him. He is 22 years of age, reads and writes, weighs about 140 pounds, and is credited with a great deal of shrewdness, pluck, and modesty.”

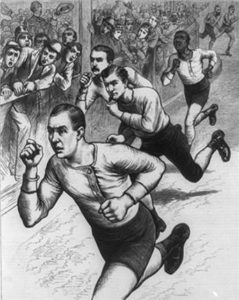

The Start

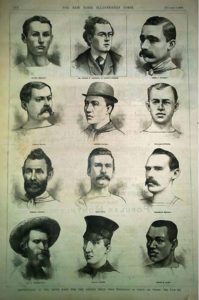

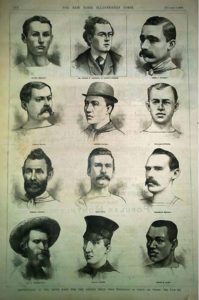

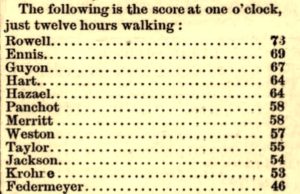

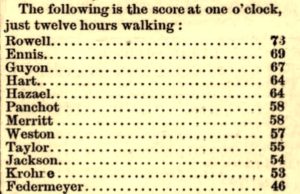

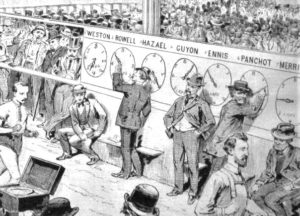

The Fifth Astley Belt race began with thirteen starters on September 22, 1879, in front of several thousand people. When the contestants appeared, O’Leary was at Hart’s side, giving him support. Hart was dressed in a gray shirt and black pants. All contestants wore large numbers painted in red on black oilskin bibs on their chests. Shortly after midnight, the word “go” was given and off they went, with George Hazael (1845-1911), of England, running fast in the lead.

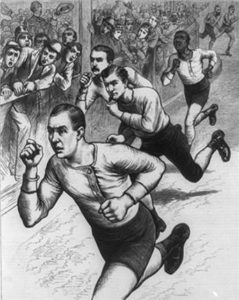

Early on, at the instructions of O’Leary, Hart dogged the heels of former champion Rowell of England, staying just a few feet behind him around the track. Rowell, who had used this strategy in the past against others, did not like it done to him. He tried to shake Hart off by sprinting at times, but Hart stuck with him in second place. This made Hart a quick favorite among the New York crowd who wanted to see the Englishman lose and cheered Hart repeatedly. A man said, “Turning the tables is fair play. That’s the game Rowell played on O’Leary on this very track when he first won the belt.” Another man replied, “Rowell wouldn’t care a button if they had the entire colored race behind him in a string. He’s come here to win that belt and all the money that goes with it.”

Hart’s backers had thought he would receive racist taunts. “He had been cautioned by his backers to pay no heed to insults, and not let them disturb his equanimity, but to his surprise, the spectators treated him with almost unvarying courtesy, and he encountered no taunts.” A drunken man did start to yell that “the colored man” should be taken off the track. The police quickly ejected the man from the building. The black spectators in the audience gathered and showed their appreciation by cheering for all the runners, not just Hart.

The news press was curious about Hart. “The colored boy Hart chews on a quill, and plods along at a rattling pace.” They were surprised that he increasingly became a great favorite, was repeatedly cheered by the crowd and received more bouquets of flowers than any other runner. Hart, who did not grow up in the South, thought it was funny that the newspapers called him a “boy” since he was 22 years old with a family.

After sixty miles, Hart gave up on trying to annoy Rowell and stuck to his own pace, fighting off cramps. “The colored youth has created more surprise than any of the other walkers. O’Leary has taken a great interest in the boy, and Hart has imitated the late champion to such perfection. He even carries the corn cobs, after the manner of his preceptor. He walks and runs most gracefully.” Some bystanders called him “a smoked Irishman.” Judge John Callahan, of the district court of New York, said that Hart “was no negro at all, but O’Leary painted.” Hart ignored it all, never complained, and implicitly obeyed O’Leary’s advice, who at times would dart out, run along with Hart, encouraging him on.

Hart received many big bouquets of flowers from spectators, including two magnificent floral horseshoes, which were put above the entrance to his tent. One had the words in flowers, “Go it, Black Dan!” Inside were two small tables covered with “Florida water, perfumed soap, a toothbrush, a hairbrush and comb, a bag of pears, some grapes, oatmeal, ginger snaps, calves’ foot jelly, crackers, eggs, a bottle of milk, a kerosene stove, and an earthen teapot. Hart’s clothes hung upon a line stretched across the tent. Everything was as neat as a bandbox.”

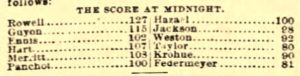

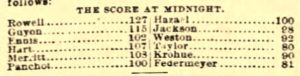

Many black spectators came out to cheer him on. Hundreds of people stood outside the building trying to get glimpses of the runners on the track through the open doors. Sportsmen doubted that he would last beyond three days, especially because of his recent six-day race in Rhode Island. He reached 100 miles in about 21 hours, 110 miles in 24 hours, and was in third place. Rowell covered 127 miles during the first 24 hours.

Day Two

On day two, after his 126th mile, Hart fell on the track and a crowd rushed to see him. O’Leary was quickly at his side, and he was carried to a nearby tent. He complained of giddiness and pains in his stomach. A rumor circulated that he had been drugged by outsiders, but O’Leary didn’t believe it. An hour later Hart recovered and returned to the track. Betters were starting to place wagers on Hart.

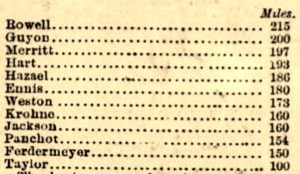

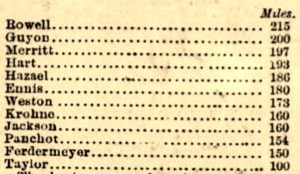

Hart later looked fresh and lively and attracted the applause of the whole building again and again. Hart was asked how he felt about the new nickname that was given to him, “Black Dan.” He said, “I hope Mr. O’Leary won’t be offended by it. I am very proud of it.” When asked how he was being treated, he replied, “Splendid. The people are very friendly to me, very nice. See how they applaud any little thing. Wait until I win and then they may cheer me all they like, and I’ll like it too. When I’m on the track and see all the faces and hear the music and the scores, I feel every step I take is bringing me so much nearer. I have a burning desire to get that belt.” After 48 hours, Hart was in fourth place with 193 miles. Rowell had 215 miles.

Day Three

Early in the morning of the third day, Hart was rolled up in blankets, put into a cab, and taken to a Turkish bath. “He slept while they were undressing him, during the bath, all through the shampooing, in the hot room, until they brought him out to cool on the canvas, and only woke up when they turned the cold water on his face. He then started with a jump and made a rush as though to get on the track and resume his march.”

Back at the track, he ate a breakfast of two mutton chops, a little bit of beefsteak, a large plate of chopped-up eggs, six pieces of toast, cornbread, and tea. He was worried about eating so much, and not leaving anything for the others. “To see him in his tent eating was as amusing a sight as can be imagined. He often laughed at the idea of being waited on by white men.”

Fred Englehardt, who was on this team, assured him that it was a pleasure to help such a good-natured chap. “While Hart sat at the little table, his eyes sparkling with delight, he knocked his knuckles on the table and with much formality called out, ‘Waiter, some water.’ When the meal was finished, he took his favorite toothpick from behind his ear, and as he lounged back in his chair, he looked sternly and said, ‘Give me my bill, and hurry up.’ Then breaking out into a ripple of laughter, he jumped up, shook himself, and with ‘This is bully,’ dashed out on the track again. A merrier, harder working little chap than Hart cannot be imagined.”

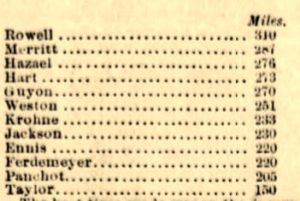

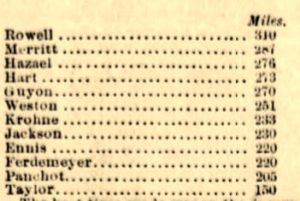

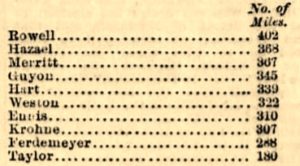

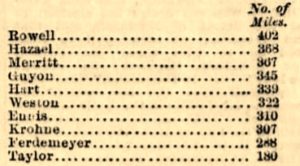

Hart was told that Weston thought he was the best man on the track, which was a surprise because he initially didn’t want Hart in the competition because he was black. Hart felt honored by that compliment. He returned to the track to cheers of, “Go it, Dan! Fetch ‘em up! Give it to ‘em!” His eyes would brighten when the band played, “Baby Mine.” At the end of day three, Hart was still in fourth place, with 273 miles. Rowell was leading with 310.

Day Four

On the fourth day, it bugged Hart to see Hazael running past him, increasing his lead. He became impatient, wanting to run after him, but both O’Leary and Englehardt insisted that he continued walking. In the early morning, they finally let him go ahead and run. Hart and Hazael started racing around the track. Sadly, while rounding a turn, Hart twisted his right ankle and fell to the ground very awkwardly. O’Leary was quickly on the track. Hart thought it was just a stumble and wanted to continue, but he was carried to his tent where his already swelling ankle was treated for two hours before he resumed his walk.

Hart still struggled and, “crawled around the track at a snail’s pace. His lips were bloodless, his eyes dim, and his limbs trembled beneath him at every step.” His trainer called him back into his tent for some needed rest.

The thousands of spectators in the Garden were being well-fed. “Sandwiches 3,000 per day; pork and beans 300 pounds of pork and two bushels of beans a day; hams, 50 a day; corned beef, 200 pounds a day; pigs’ feet 4,000 sold up to noon; pickled tongues, 6,300; pies, 250 every 24 hours; java coffee, 200 pounds; oysters, 5,000 a day; roast beef, 100 pounds a day. In addition to these, there have been many thousands of barrels of chicken and lobster salad consumed, along with several thousand kegs of beer.”

Rowell reached 402 miles by the end of day four, and Hart reached 339 miles and had fallen to fifth place. Outside of the building, racist comments were heard against Hart that were not appreciated by black friends who had money on their new hero.

Day Five

During the long early morning hours of day five, a cry was heard from Hart’s tent, “Put him out!” People feared that someone was trying to assault Hart. But soon Englehardt appeared at the door of the canvas house and assured everyone that Hart was fine. “He explained that one of the attendants who had not slept for several nights, who was in the act of cooking Hart’s supper, had laid his head on his hand for a moment on the table beside the gas stove and his hat took fire. One side of his head was in flames, but he slept on and took no notice of it.” They rescued the man and “put him out.” Such were the hazards of being on a 19th-century crew.

The attention of Hart’s crew was impressive. “When the colored boy drew back the flap of the tent and entered, the men in there were lounging in chairs or lying on the floor. The moment they saw him, they were on their feet. Two of them took him in their arms and laid him on the cot bed as gently, as kindly, as tenderly and with as much care as if he were the son of a duchess, or better still, their own flesh and blood. It was an exquisite scene, and it brought out qualities that did honor to human nature.”

A well-known trainer was asked who he thought was the best walker on the track. His reply was, “Black Dan, without any doubt. That boy has not had a fair show here. He ran a race only a week before he came in here. It’s amazing to see what he is doing. It’s my opinion, Dan will wear the belt yet.”

The event of the day that received the most attention was when the race leader, Rowell became seriously sick and believed that he had been poisoned by someone trying to make him fail. He had eaten some grapes that had been handed over the rail to him by a spectator and then began to feel hot and sick with sore eyes. After five hours of being treated by his trainers and a doctor, Rowell returned to the track, still holding the lead, and looked somewhat pale. Hart felt great sympathy for him, expressed his sorrow, and gave him a picture of himself as a gift. Rowell said, “Thank you, old fellow.” Rowell felt he could still win but was disappointed that the 600-mile barrier looked like it was now out of his reach.

Hart also was given grapes and a tempting-looking banana, perhaps by the same man. He had wanted to eat the banana but remembered O’Leary’s firm instructions about being careful where he obtained food, handed the food over to his trainer, and it was thrown away. Other runners received the suspect grapes but also did not eat them.

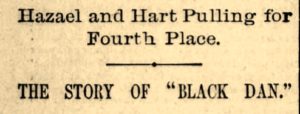

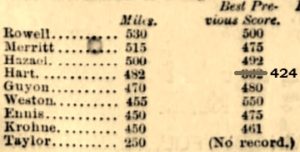

During the evening, Hart dogged the heels of Edward Payson Weston who was about ten miles behind him. A typical racist treatment of the time could be read in the New York Daily Herald. “Why look at the darkey! See him sidle up beside Weston. Up they come, walking like shot, the darkey just a step behind the actor and watching him like a thief.” Weston was very annoyed with Hart’s dogging and turned around showing a “puffed face” at Hart and complained to O’Leary. For ten minutes this went on until Weston finally left the track for his tent and Hart followed, almost also going into the tent, causing the crowd to roar with laughter. At the end of day five, Hart was in fourth place with 415 miles. Rowell had 453 miles with an eleven-mile lead on the rest of the field

Day Six

On the final day, Hart fought hard to keep fourth place, running ahead of George W. Guyon (1853-1933) of Chicago, Illinois. It was a continuous fight between the two. “First, one would force the pace to run and then the other. This was just what people enjoyed, and they did what they could to urge them on.” Eventually, Hart got an advantage while Guyon was in his tent and the lead increased to three miles.

O’Leary was pleased with Hart’s performance and said, “If he had not sprained his ankle, he would have done much better, but as it is he is making a good race. He is receiving telegrams and letters from all over the country and flowers and presents are pouring in by the bushel. Hart is a good boy, and I am fond of him. He will make his fortune at walking.”

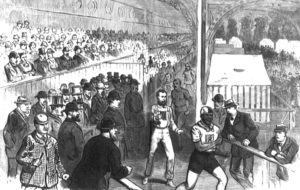

The building was filled with thousands of people. “A ceaseless human tide streamed in every minute through the great main entrance. Every seat was taken up. You can scarcely get within six feet of either rail. All the narrower walks were blocked and impassable. The great central arena was alive with one moving, shouting mass.”

When Hart ran past 450 miles, the crowd shouted with great enthusiasm. By achieving that milestone, he would have a share of the gate receipts. Guyon was also trying to reach 450 miles and was very annoyed when Hart seemed to block his efforts to pass him. He even complained to the referee, George W. Atkinson, who gave him a warning. O’Leary encouraged him on to dog Guyon’s heels. O’Leary ran behind Hart, clapping his hands, telling him to run faster. Finally, Guyon had enough of being pestered and retired to his tent. One reporter, hoping for Hart’s failure wrote, “The whole thing was looked on as a mean trick of the colored boy to secure an unfair advantage, as Guyon is by far the better of the two.”

The Finish

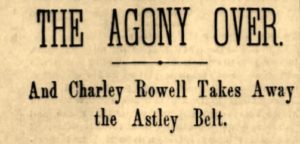

In the end, the Englishman, Rowell won the Astley Belt again with 530 miles. “A perfect roar went up from all sides as Rowell passed along with the Stars and Stripes over his shoulders. Cheer after cheer went up until all else was drowned. People grew frantic with excitement and stood upon one another in an eager effort to see the track. Hats were thrown in the air, handkerchiefs waved, and feet stamped, until the very building shook. The dust and smoke rushed upward in volumes so dense that even the electric lights paled and seemed to flicker.”

Hart had held onto fourth place, finishing with 482 miles, twelve miles ahead of Guyon, and 27 miles ahead of legendary Weston. The band played, “Home Sweet Home,” and the audience started to leave the building. “It was no small matter to get an audience of something like 10,000 persons out of five narrow doors, and it was more than half an hour before everybody was out. The crush at the doors was tremendous, and thousands strolled about the house waiting wisely for a turn. Small boys and ambitious young men walked short spurts on the track and looked curiously at the tents, but at length, everybody was out, as well as the lights.”

Hart smiled and walked into his tent with the air of a champion. He sat down on a chair, stretched his legs out before him, closed his eyes, and sank back on the chair. Someone pulled a joke and yelled “tickets” causing Hart to rouse startled. O’Leary said, “Well, Frank, you’ve done well.” Hart smiled and replied, “The only thing I am sorry for is that the belt is going back to England.”

While Hart’s team was preparing to leave the building, he chatted pleasantly with those surrounding him. He said he was not tired and felt first-rate. He did admit that he was a little sleepy but thought he could have continued to walk many more miles if needed. Looking at the mass of floral arrangements around his tent, he guessed that he would have to hire an express wagon to get them all home. When it was time to go, Hart walked out of the 27th Street entrance of Madison Square Garden between his trainers where a carriage was waiting for him. “The crowd cheered him as he passed, and hundreds of pleasant words that were sent after him seemed to please him. He got into the carriage with O’Leary and Engelhardt, and as soon as the door was closed sank back on the cushions and closing his eyes, said, ‘My, wasn’t that a crowd. Never saw such a big crowd in all my life!’”

As the carriage drove down the road, a crowd of adoring fans followed and tried their best to see him through the window. When he reached St. Omer Hotel, a policeman had to clear the sidewalk so he could enter the hotel. On reaching his room, he was asked what he wanted. He requested stewed kidneys, buttered toast, tea, and some mincemeat pie. His massive amount of flower bouquets filled a parlor in the hotel.

Return to Boston as a Hero

The next day, Hart arrived by train back in Boston and was met by a large crowd at the depot which pleased him. Asked how he felt, he replied, “I am all right, feel good, and should feel so, as I am satisfied that my fellow citizens have appreciated my efforts to recapture the belt.” A banquet was held that evening in his honor, “participated in not only by citizens of his own color but by all true Americans”

![]()

![]()

Frank Hart, the first truly successful black ultrarunner, had competed on the world’s biggest stage. The world was surprised and noticed. “Hart, the negro, who entered the contest almost under protest, and who was looked upon almost slightingly by his fellows on the track, won not only a good record and place but that which was of greater value, respect, and admiration for his modest, manly bearing and plucky work. To be less than fifty miles behind the winner under the circumstances is a magnificent record, and the ablest pedestrians may well regard with apprehension this healthy, lively fellow, who is so heartily in love with his work, and who instead of saving himself, seems always to have vitality to spare.”

After his exhausting, surprising, six-day Astley Belt performance, Hart wisely took time off from competing in races but put on exhibitions at races for a couple of months. “Frank Hart of the late Astley belt contest came on the track and gave some very pretty exhibition spins. He was loudly cheered, not alone by the audience, but also by the pedestrians on the track.” Receptions were held in his honor, including one put on by the Centennial Club of Cambridge, Massachusetts held at Payne Memorial Hall. He was given an elegant solid silver water service by his Boston friends.

Outside of Boston, Hart had his critics. In Chicago, it was falsely reported that during the recent Astley Belt race, he had been forced to run like a slave. “His trainers forced the negro pedestrian to keep upon the track. He was wretchedly exhausted and made repeated efforts to escape from the ring, but as often they compelled him to go on with the idiotic self-torment.” In New York, they praised him but considered him to be an exception to his race. “This dusky young Apollo is a picture of grace and power. It is not the physique that we associate with men of his color. There is none of the slouch of the plantation about him. He is in earnest, with just intent on his work.”

In Washington D.C., thoughts were political. “It is now intimated that Hart, the colored walkist should have been nominated for Governor in Massachusetts. He shows remarkable running powers.”

People were stunned at how much money Hart won. “Won’t some philanthropic stalwart at once organize a bank to take care of his money for him? A kind of a Freedman’s Bank.”

Sources:

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Apr 13, 25-27, Sep 3, 10, 22-23, 29-30, 1879

- The Fitchburg Sentinel (Massachusetts), May 31, 1879

- New York Daily Herald (New York), Aug 29, Sep 23-28, 1879

- The Times-Picayune (New Orleans), Sep 2, 1879

- The Philadelphia Inquirer (Pennsylvania), Sep 9, 1879

- The Baltimore Sun (Maryland), Sep 15, 1879

- The Buffalo Commercial (New York), Sep 22, 1879

- The New York Times (New York), Sep 22, 1879

- The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (New York), Sep 23, 1879

- The Sun (New York), Sep 23, 1879

- Chicago Daily Telegraph (Illinois), Sep 23, 1879

- Buffalo Courier (New York), Sep 28, 1879

- Boston Post (Massachusetts), Sep 29, 1879

- Reading Times (Pennsylvania), Sep 22, 29, 1879

- Daily Republican (Wilmington, Delaware), Oct 7, 1879