Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 27:54 — 32.1MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

You can read, listen, or watch

| Please consider supporting ultrarunning history by signing up to contribute a little each month through Patreon. Visit https://www.patreon.com/ultrarunninghistory |

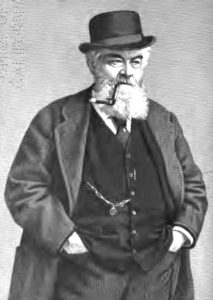

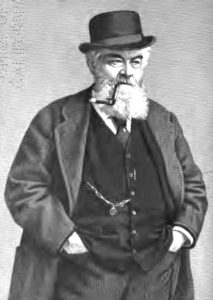

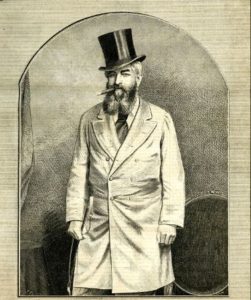

Sir John Dugdale Astley (1828-1894) was a member of Parliament representing North Lincolnshire. He grew up in a wealthy family and was a lieutenant colonel in the Scots Fusilier Guards, serving in the 1854 Crimea War where he was wounded in the neck at the Battle of Alma. He was a great sportsman and while young, was an elite runner at the sprint distances.

Astley was truly a “larger than life” character. “He was a big, burly, old man, fond of strong language and strong drink. Wherever he went he was made conspicuous by his large figure, white hair and beard, the enormous cigar, never out of his mouth, save when he was eating, drinking or sleeping, his strident voice and his frequent, boisterous laugh.” A friend said, “He must have smoked more miles of cigars than any man living.”

Astley also had a passion for horses and boxing and wagered large sums of money. He lost a small fortune betting against O’Leary in the Edward Payson Weston vs. Daniel O’Leary II race of 1877 (see episode 105). Astley introduced the first belt (not belt buckle), into ultrarunning when he awarded William Gale a massive belt for accomplishing 4,000 quarter miles in 4,000 consecutive periods of ten minutes during October-November 1877 for 28 days. Championship belts had been introduced in boxing as early as 1810, and Asley brought the belt into the sport of pedestrianism. “Sir John Astley girded Gale’s waist with a belt of crimson velvet and massive silver. But the belt was too large, so amid much applause and some little merriment, it was slung across one of his shoulders.”

Plans for the Long-Distance Championship for the Astley Belt

Go-As-You-Please Rules Introduced

Skeptics

One sporting newspaper called the planned event, “Sir John Astley’s Punch and Judy performance that would cause P.T. Barnum himself to hold his breath in awe.” It was mocked that the English runners would have their faces be painted like clowns and that the judges would be in wigs with false noses and spectacles.

Runners Enter the Race

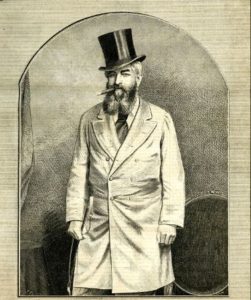

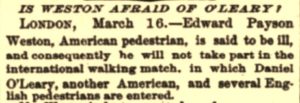

By mid-February, some British entries were coming in for the tournament. They had to initially pay £1 to be screened by The Sporting Life, and if accepted pay an additional £9 to be formally entered. O’Leary’s formal entrants’ fee was late, but Astley wisely extended the deadline.

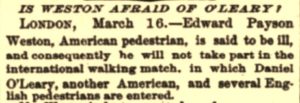

Weston underestimated the historic significance of the upcoming event. He later gave a lame excuse of illness and presented a doctor’s note as proof. The New York Times properly speculated the Weston was afraid of O’Leary.

British Runners Prepare

The most competitive British ultrarunners were training hard. Many of them participated in a 26-hour race, held on February 23, 1878, on the track in Agricultural Hall in London. William Howes of London won with 129 miles in 24:20, setting a new world record of 127 miles 1210 yards in 24 hours. Howes also broke the world 100-mile walking record, reaching 100 miles in 18:08:20. Clearly the British were emerging as highly competitive long-distance pedestrians.

![]()

![]()

The Manchester race was the first known “go-as-you-please” six-day race in history, where the contestants could make “the best of his way, walking or running.” Hazael won the race on a terrible track with only 240 miles and Crossland went away severely injured, causing him to withdraw from the upcoming tournament.

O’Leary Arrives in England

A committee was formed to manage the event, comprising of “numerous members of the aristocracy, and all the titled supporters of the national pastime of the turf.” To stir up attention, the promoters started to announce that some prominent runners were entered who were not.

The winner would be awarded a four-foot-long silver and gold “challenge belt” weighing five pounds and he must defend the belt during an 18-month period with no more than two matches within a year. O’Leary felt confident and said, “I think there are about 550 miles in these boots between now and the end of the week”.

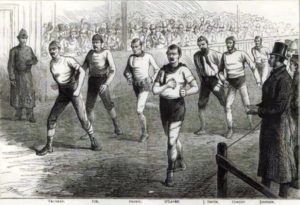

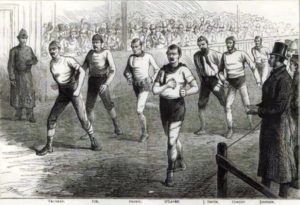

The Start

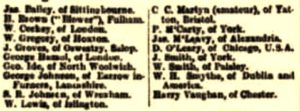

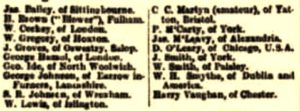

The 18 starters were: James Bailey of Stittingbourne, Henry “Blower” Brown of Fulham, William “Corkey” Gentleman of London, W. Gregory of Hoxton, Joseph Groves of Oswestry, George Hazael of London, George Ide of North Woolwich, George Johnson of Barrow-in-Furness, S. R. Johnson of Wrexham, Walter Lewis of Islington, Charles C. Martyrn of Yatton, Pat McCarty of York, James McLeavy of Alexandria, Daniel O’Leary of Chicago, J. Smith of York, William Smith of Paisley, W. R. Smythe of Dublin, and Henry “Harry” Vaughan, of Chester.

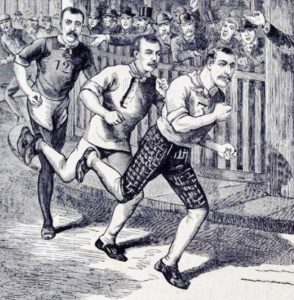

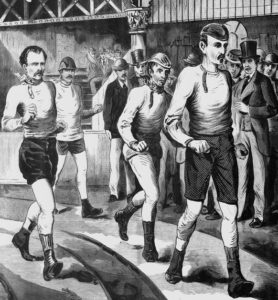

During the early morning hours, spectators were not allowed in, only runners, attendants, race staff, and some of the press. Some competitors started running fast, others jogged carefully, and O’Leary started out using his proven style of walking. “It was a strange sight as they settled down to their work, the eighteen men, in their varied costumes, some walking steadily, some trotting, some running, some in groups, others individuals.”

George Hazael Quits Early

Early on during the race, Hazael tried to use some brash tactics against O’Leary. He was walking in the opposite direction of O’Leary. “When he passed the Irishman on each curve, he would verbally challenge O’Leary, attempting to get him upset. On one turn Hazael said, ‘I’ll kill this wonderful man before I am done with him.’” As Hazael gained a lead, it caused O’Leary to worry and start running which alarmed his handler, Albert Smith, who begged him to stop running. O’Leary replied, “Leave me alone. I know what I am about.”

After 90 minutes, Hazael was still ahead of O’Leary by a mile or two. This really bugged O’Leary. “He couldn’t stand this bitter, slouching, personal competitor. Therefore, he vowed to beat him.” Hazael was warned by the judges that he would be disqualified if he continued his unsportsmanlike behavior. He soon slowed significantly, without the breath to continue to trash-talk O’Leary, and he was the first to quit the race, reaching only 50 miles in 11:54:36, far back in 15th place. “Hazael retired in disgust and contempt for the new order of pedestrianism.” One British sports critic called Hazael’s effort “utterly contemptible.” In the coming years Hazael would change his mind and become one of the greatest six-day runners ever, the first to break the 600-mile barrier three years later.

Smythe Fizzles

W. H. Smythe (1849-), age 29, of Dublin Ireland was among the favorites. About a year earlier, he had been the first British walker to reach 500 miles in six days in a solo event. He had also raced against O’Leary in Liverpool in a two-man relay for six days. But in this contest, his first six-day race against others, he was a disappointment. “He had gotten himself a suit of sables (robes worn by royalty) and was dubbed “Hamlet” as soon as he appeared on the track. Speed he had none. His poor performance should be a lesson to those who are ready to accept records of things they don’t understand.” (Smythe would only reach 175 miles).

Corkey Runs Well

After 12 hours, O’Leary pulled into the lead with 66 miles but was closely followed by a runner called, “Corkey.”

The race report included, “The chief feature of the walk up to this point was the extraordinarily good running of Corkey, an old pedestrian, some 45 years of age, but who still seemed to skim over the ground with lightness of an Italian greyhound.” At 18 hours, Corkey was in the lead with 87 miles, alternately walking a running, with a five-mile lead over O’Leary. Corkey was the first to reach 100 miles.

As the day went on, most of the competitors had given up attempts to truly run. O’Leary had slowed to a trot since midday. After the first day, the score was O’Leary 117, Corkey 113, and Vaughan 102 miles. About 5,000 spectators were asked to leave the building for the night.

Day Two

Blower Brown soon moved up to compete for third place against Vaughn. Of all the competitors, Brown was seen running the most often.

Blower Brown

Day Three

Henry Vaughan

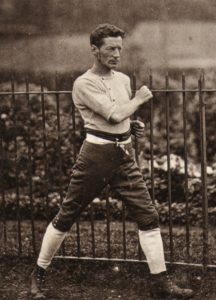

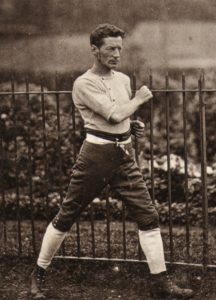

Henry “Harry” Vaughan (1848-1888), age 29, was a carpenter/architect from Chester, England. He was nearly six feet tall, thin, and walked very upright with a long stride. Vaughan began his walking career in 1870 when he won a two-mile race and became a professional in 1876. That year, also in the Agricultural Hall, he broke O’Leary’s 100-mile world walking record with 18:51:35 by about two minutes, and also broke Weston’s 24-hour world walking mark (117) with 120 miles.

Vaughan had been the pre-race favorite among the betters, 5-3 odds. Betters on Vaughan stood to win a staggering £100,000 if he won (about $13 million in today’s value). He had kept a steady walking pace, “a long, striding giant-like pace that was the admiration of everybody. His body is well-balanced, his head is poised upon his shoulders clean and free, and his manner is characterized by a perfect calmness.”

Halfway through day three, O’Leary was at 240 miles with a ten-mile lead over Vaughn. “Unfortunately, however, Vaughan is suffering from sore feet. O’Leary seems in first-rate order, and beyond a slight blister on the little toe of his left foot, his feet show no signs of having suffered from the amount of exercise he has lately undergone.” A huge crowd of about 8,000 people attended in the evening. A special “ten-shilling” area was set up for first-class viewing.

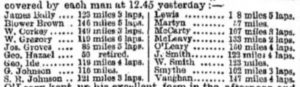

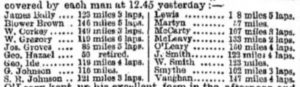

At the end of day three, the score was O’Leary 288, Vaughan 270, and Brown also at 270 miles. Corkey, who had been with the frontrunners in the early days, had fallen off dramatically.

Day Four

On day four, the press was getting bored. “During this afternoon, the attendance at the walk has increased, but the proceedings have been most monotonous.” However, they were fascinated with the reaction of the spectators. “In an age of sensations, and now that the rage for pedestrian feats is at its height, it is too much to expect that spectators will immediately grow tired of such displays.”

It was surprising to many that running did not seem advantageous over walking. “It is very remarkable that O’Leary has kept very constantly to the walking pace, whereas those who have done the most running do not seem to have gained anything by extra speed so attained. The present race affords a notable proof that walking is the natural pace of man, and that it is the most serviceable pace for all long distances.”

Vaughan continued to press against O’Leary’s lead. “Vaughan is walking in such find style that the American will have all his work to do.” Brown’s style was said to be “a comical kind of trot, which was intensely amusing.”

At the end of day four, the score was O’Leary 373, Vaughan 360, Brown 337.

Day Five

O’Leary was said to wear an anxious look on his face. Vaughan, the Brit’s remaining hope for victory, reached 400 miles about four hours after O’Leary. “The announcement on the scoring board being received with loud cheers, which were repeated when he was shortly afterwards presented with a handsome bouquet trimmed with the national colors, he being then just 14 miles in the rear.”

During the day in London, a false rumor spread that something was wrong with O’Leary which caused a rush of spectators to come to the building. They were clearly favoring Vaughan. But they were alarmed to see their hero with his bruised feet wrapped in cotton wool. “He strained every nerve to reduce the gap between himself and his adversary, but although he has frequently trotted short distances, O’Leary holds his own.”

Observers noticed that “the ruck of the competitors presented a forlorn, destitute, ragged, and even dirty appearance. Their guernseys and running drawers looked as if they had not seen soap and water for many weeks. Their boots were hanging to their feet by shreds. Abject poverty seemed settled on every countenance, and most of them looked as if they were walking for dear life.”

Vaughan, on the outer, longer track, used a strategy to match O’Leary on the shorter inner track, lap for lap and follow him closely to close the gap. But evidently O’Leary disliked racing side by side and every chance he got he would suddenly reverse his direction after a mile to try to get away from Vaughan, but usually his shadow would follow him. Late in the evening many thought Vaughan would catch up to O’Leary.

O’Leary later said, “Vaughan is a gallant walker and a good square fellow. We watched each other like enemies but there was no feeling of envy or anger. Vaughan’s friends were by far the most numerous. When they handed him bouquets, he would pass them over to me to smell, and on the next turn I would hand them back. The wild applause for Vaughan had no effect upon me.”

By 10:00 p.m. the hall was densely crowded. The mob shouted whenever two men got near each other, apparently oblivious of the fact that one was in reality 100 miles ahead of the other. At the end of day five, the score was O’Leary 457, Vaughan, 441, and Brown 416. The fourth runner, Ide was 65 miles behind Brown.

Day Six

As usual, the building was cleared of spectators for the night. But for this last morning, many remained lined up outside the building to make sure they did not lose their chance on getting back in. O’Leary slowly plodded along the track for several hours during the wee hours of the morning while Vaughan and Brown rested. “This has enabled O’Leary to obtain such a lead that nothing less than a total collapse can deprive him of victory.” He finally retired but told his trainer to wake him up the moment that Vaughan reappeared on the track. By dawn his lead was 24 miles. “It was now plain to the most obtuse, that nothing but a sheer breakdown could prevent the prize going to the American.”

“As the morning advanced, the crowds began to pour into the building, and notwithstanding that there were other competitors on the track, eyes were strained, and lungs were used only for O’Leary and Vaughan. From the crowded gallery as well as from the floor did shout after shout go forth as first one and then the other put on a spurt.”

Brown had been washed and wore a clean set of flannels, with a rose-colored neckerchief and short pants to match. A lady said he looked “quite lovely.” But O’Leary and Vaughan had a much different look. “They were travel-stained and stale, the grime of a week was on both, and no tramp from Manchester in search of employment he did not want, ever presented a more doleful appearance.”

O’Leary’s leg began to swell and cramp. He looked worn out and no longer held his arms forward. But he refused to leave the track for any rest, fearing that if he did, he would not be able to start walking again. For eighteen straight hours he never left the track for one second. His leg swelled to twice the normal size, was stiff, but he felt no significant pain. At 2:47 p.m. he reached 500 miles to “immense applause” setting a new world record for that distance of 133:44:00.

By late afternoon, there were about 14,000 people in the building. “High above the gallery some adventurous youths had perched themselves in the girders, and once or twice it seemed that there would be a ghastly accident. A shaky scaffolding in mid-air was also tested to its uttermost limit, but happily with no fatal or otherwise unpleasant consequence.”

O’Leary then retired to his tent. There was tremendous cheering and the band played, “See the Conquering Hero Comes.” Brown and a couple of others continued. O’Leary went to his dressing room, quickly escaped from the mob, and took a cab for his hotel.

Vaughan came back out, supported by his trainer and attendant. and walked a lap on O’Leary’s track. He received cheers from hundreds who had not been able to find O’Leary. “At 8:32, the mob broke in and swarmed all over the course, it might be said at the invitation of the band, who played, ‘God save the Queen,’” At that point because of the chaos, the race was declared finished.

Within a week or two, O’Leary was eventually awarded the “Challenge Belt.” It included seven oblong squares, 3×2 inches of solid silver with embossed edges. The center piece was made of solid gold with raised letters that read, “Long distance champion of the world.” On the left silver square was a figure of a runner and on the right was a figure of a walker. O’Leary later remarked, “They put the runner ahead, because they wanted him to win.” On the buckle plate was inscribed O’Leary’s name, distance of 520 ¼ miles and time of 138 hours, 48 minutes.

Reaction

![]()

![]()

But was it totally fair? It was pointed out the O’Leary had a track to himself, while the other seventeen had to jostle and struggle on the same track. Certainly, during the early days, this created a disadvantage for Vaughan. Because Vaughan had to pass so many runners on the outside, it was estimated that he walked 12-15 miles more than the distance he was credited for.

English sportsmen also pointed out that O’Leary had better attendants and better food. “Vaughan had to fare on lumps of indigestible steak, which made him retch, or a mixture of beer in a teacup, and rice pudding equally unstomachable. Also, not one of the competitors except O’Leary had a second pair of boots, and the boots worn were too narrow-soled.”

As usual, there were also plenty of negative reactions to the event. From London it was written, “One of these days, when one of these poor fellows, dazzled with the distant prospect of gold, drops down dead on the track, science will be satisfied, sport appeased, and public indignation aroused. A grave responsibility is incurred by such as pander to an unhealthy excitement. Pedestrians will go on doing the ‘best time on record’ until they drop down dead. Their requiem will still be the wheezy brass band and the hollow cheers of the crowd.”

O’Leary returns to Chicago

The parts of this Six-Day Race series:

- Part 1: (1773-1870) The Birth

- Part 2: (1870-1874) Edward Payson Weston

- Part 3: (1874) P.T. Barnum – Ultrarunning Promoter

- Part 4: (1875) First Six Day Race

- Part 5: (1875) Daniel O’Leary

- Part 6: (1875) Weston vs. O’Leary

- Part 7: (1876) Weston Invades England

- Part 8: (1876) First Women’s Six-Day Race

- Part 9: (1876) Women’s Six-day Frenzy

- Part 10: (1876) Grand Walking Tournament

- Part 11: (1877) O’Leary vs Weston II

- Part 12: (1878) First Astley Belt Race

- Part 13: (1878) Second Astley Belt Race

- Part 14: (1879) Third Astley Belt Race – Part 1

- Part 15: (1879) Third Astley Belt Race – Part 2

- Part 16: (1879) Women’s International Six-Day

Sources:

- Tom Osler and Ed Dodd, Ultra-marathoning: The Next Challenge

- P. S. Marshall, King of Peds

- Matthew Algeo, Pedestrianism: When Watching People Walk Was America’s Favorite Spectator Sport

- P. S. Marshall, “Henry or ‘Harry’ Vaughan: Speed Walker Extraordinaire!”

- Fifty Years of My Life in the World of Sport at Home and Abroad

- P. S. Marshall, “Corkey: One Time Long-Distance World-Record Holder”

- John A. Lucus “Pedestrianism and the Struggle of the Sir John Astley Belt 1878-1879”

- Fifeshire Journal (Scotland), Nov 22, 1877

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Dec 9-10, 14, 1877, Feb 25-26, 1878

- Newcastle Journal (Northumberland, England), Jan 3, 1878

- Southern Reporter (Selkirkshire, Scotland), Jan 3, 1878

- The Globe (London, England), Jan 19, Mar 20-23, 1878

- The Referee (London, England), Jan 20, Feb 24, March 10, 25, 1878

- Sheffield Daily Telegraph (England), Jan 21, 1878

- Sussex Advertiser (England), Jan 22, 1878

- The Graphic (London England), Jan 27, Feb 9, 1878

- Richmond & Ripon Chronicle (Yorkshire, England), Feb 23, 1878

- Athletic News (Lancashire, England), Feb 23, Mar 2, 1878

- Louis Post-Dispatch (Missouri), Feb 25, 1878

- York Herald (Yorkshire, England), Feb 25, 1878

- Edinburgh Evening News (Scotland), Feb 26, 28 1878

- Bolton Evening News (Lancashire, England), Feb 27, 1878

- Manchester Courier (England), Mar 1, 1878

- Bell’s Life in London (England), Mar 2, 1878

- Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News (London, England), Mar 9, 1878

- The New York Times (New York), Mar 17, 1878

- London Evening Standard (England), Mar 18-19, 23, 1878

- Daily News (London, England), Mar 20, 1878

- The Daily Telegraph (London, England), Mar 21, 1878

- Liverpool Mercury (England), Mar 21, 1878

- Citizen (Gloucester, England), Mar 21, 1878

- Manchester Evening News (England), Mar 21-22, 1878

- The Times (London, England), Mar 21, 1878

- Aberdeen Journal (Scotland), Mar 22, 1878

- The Era (London, England), Mar 24, 1878

- The Sportsman (London, England), Mar 25-1878

- The Yorkshire Herald (York, England), Mar 28, 1878

- The New York Times (New York), Apr 1, 1878