Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 26:48 — 31.5MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

You can read, listen, or watch

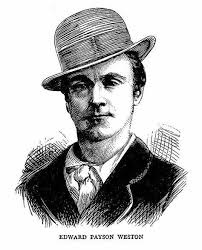

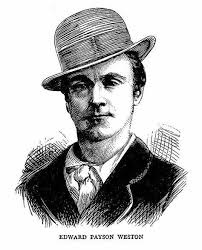

By March 1875, Edward Payson Weston, from New York City, was on top of the ultrarunning world (called Pedestrianism). He had just won the first six-day race in history, was the only person who had ever walked 500 miles in six days and held the 24-hour world walking record of 115 miles. Through his efforts and the promotion of P.T. Barnum, the sport had been given a rebirth and was on the front pages of newspapers across America.

Weston had won hundreds of thousands of dollars in today’s value for his exploits and obviously others wanted a piece of this action too. Was Weston one of a kind, or would others succeed in dethroning him? A true rival did emerge from Chicago, an Irishman who worked hard to try to become the best, Daniel O’Leary.

| Please consider becoming a patron of ultrarunning history. Help to preserve this history by signing up to contribute a few dollars each month through Patreon. Visit https://ultrarunninghistory.com/member |

Others Try to be Six-Day Kings

In April 1875, Allen Brown claimed to walk 500 miles in six days in Nashville, “the first pedestrian who has accomplished the feat without a charge of trickery.” It is very unlikely that this was legitimate. Brown was unknown and was never again mentioned in connection with Pedestrianism. Brown was just a pretender, but a true contender immerged in Chicago, Illinois.

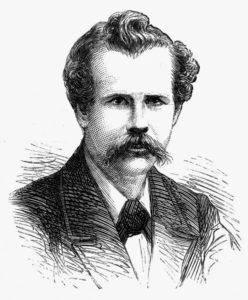

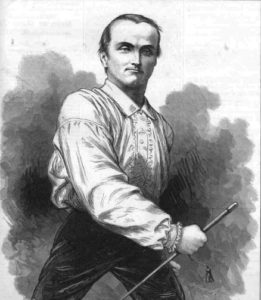

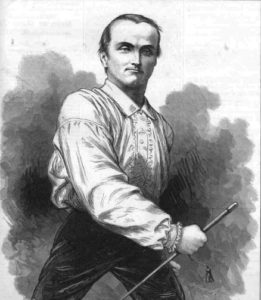

Daniel O’Leary

Under great difficulties, he was able to get a good education in Ireland. “In the village playground, amongst his classmates, he showed quite a preeminence in athletic sports, while he was yet in his teens. He was the ringleader of all the boys in the locality and was a favorite.” During his late teens he worked hard for two years in the interest of Ireland with all his energy and when free, fled the taxation coming.

In 1865, at the age of nineteen, like so many other Irish, he immigrated to America. He could not find work in New York City, so he settled in Chicago, where he first worked in a lumber yard. He next sold pictures door-to-door for B. Bierfield and then sold Bibles door-to-door. After the tragic massive Chicago fire of 1871, he became financially crippled and because of so many homeless people in Chicago, he had to peddle books in surrounding villages. He built up his endurance from speed walking his routes. It was said that when he tried to sell books to people, that many told him to “take a walk,” so he did.

O’Leary Takes up Long-Distance Walking

In 1874, O’Leary was a tailor and toymaker in the heart of Chicago. He overheard a group discussing Weston’s walking exploits, including his attempts to walk 500 miles in six days. One person said that only a Yankee could accomplish the feat. Another commented that Weston was planning on going to Europe. O’Leary said, “If he dropped into Ireland on the way he’d get beaten so bad that he’d never again call himself a walker.” Everyone laughed at him. He finally said that he thought he could beat Weston. They then roared with laughter.

O’Leary’s First 100-mile Walk

![]()

![]()

O’Leary reached his goal and finished in 23:17:58. It was more than two hours slower than Weston’s best, but he proved that an Irishman could walk 100 miles in less than 24 hours. His friends presented him with the “Championship Pedestrian Medal of the United States.” But in reality, Weston was recognized by the national public as the premier American Pedestrian. O’Leary believed he could beat him and started to issue public challenges, which Weston ignored.

A month later, O’Leary improved and walked 106 miles in 23:27:13. He was becoming the darling walker of Chicago and started making good money doing it. O’Leary followed news of Weston’s 1874 failures in walking 500 miles in six days (see episode 94) and wanted to accomplish it before Weston but could not raise enough financial support to take it on. He needed to go on the road and gain national fame. In October 1874, he walked 200 miles in 36:29 (moving time) at a rink in St. Louis, Missouri.

Chicago Hero

![]()

![]()

After Weston finally accomplished 500 miles in six days in December of 1874 (see episode 95), O’Leary again publicly challenged Weston to a six-day walking match for a staggering amount of $10,000, but was brushed off again by Weston who said, “Make a good record first and meet me after.” To Weston at the time, O’Leary was just one of a long line of pretenders. Because Weston was at the top of the sport, he did not want to share the spotlight with him or anyone else.

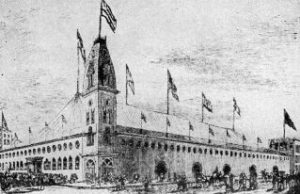

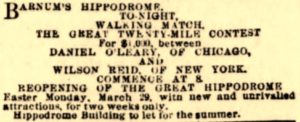

O’Leary in the Hippodrome

To get the national attention he craved, O’Leary knew that he needed to perform his abilities in the pedestrian capital of the world, New York City. In March 1875, after the first historic six-day race held in P.T. Barnum’s New York City Hippodrome, won by Weston, O’Leary made his way to the Hippodrome too.

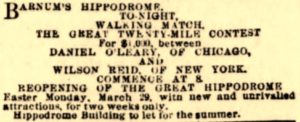

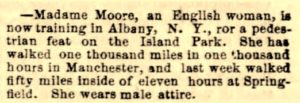

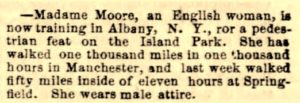

Final Pedestrians in the Hippodrome – Battle of the Sexes

At the end of March 1875, P.T. Barnum re-opened his massive New York Hippodrome for a final two-week season before taking his circus on the road. He decided to schedule one last Pedestrian race in Hippodrome to kick off the finale. If the crowds came in to watch a man walk for hours, what a about a woman? Not only did Barnum create the first six-day race, he also started the American era of professional woman pedestrians, also called, “pedestriennes.”

M’lle Lola vs. William E Harding

![]()

![]()

The male pedestrian, Harding, had been trying to become a professional pedestrian and a few months earlier, in November 1874, lost a race against Edward Mullen by 15 minutes, walking 212 miles from Jersey City to Philadelphia and back. He jumped at the chance to walk in the Hippodrome, even against a woman.

The Lola-Harding race was held on the same track in the Hippodrome used by the first six-day race won by Weston. Harding would be required to walk 50 miles in ten and a half hours, and Lola would be required to walk 30 miles in that same time.

The Race – Man vs. Woman

![]()

![]()

The race went on throughout the day but had to be halted temporarily during of the “Blue Beard” procession. Harding reached 25 miles in about 5:15. “The band struck up a lively tune and Harding spun around the track at a terrific gait, little Lola also making good time.” Lola reached 25 miles in 8:18 while Harding was at about 40 miles. Lola sped up to a 12-minute-mile and finished her 30 miles in 9:59 for the win. Harding finished his 50 miles in 10:49:57. Even with his 31-minute head start, Lola crossed her finish line about 18 minutes before Harding crossed his.

In the years to come M’lle Lola would continue as a female pedestrian but her true fame came as the most daring female trapeze artist in America, “The Queen of the Trapeze,” who performed to crowded houses.

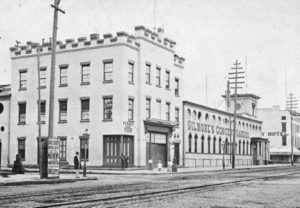

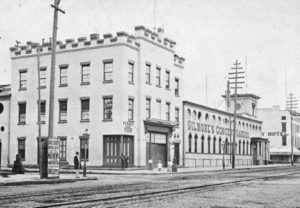

Barnum’s Hippodrome Closes

Barnum retired from promoting pedestrianism, left the Hippodrome empty, but ultrarunning history would continue in that venue during the years to come. William Henry Vanderbilt (1821-1885) owned the property that was leased for the Hippodrome. After the circus vacated, band leader Patrick Gilmore (1829-1892) leased the property for concerts, flower shows, beauty contests, dog shows, and boxing matches. The venue was renamed Gilmore’s Concert Garden and opened three months later in July 1875. A permanent roof was added around 1876. It became one of the most popular venues in the city and eventually in 1879 was renamed Madison Square Garden.

O’Leary’s First Six-Day Attempt

Even with that accomplishment, Weston still wasn’t interested in a match against O’Leary. How would O’Leary perform in a six-day match? O’Leary wanted to prove to Weston and the world that he could do 500 miles in six-days too. The Chicago Tribune reported on their favorite pedestrian, “O’Leary, who less than a year ago, was utterly unknown in pedestrian circles, has, within a very brief time, accomplished feats which have placed him at the very head of those who follow professionally the ‘heel-and-toe’ exercise. His performances against time have outrivaled Weston, who resisted all efforts to bring him into a trial of speed and endurance.”

O’Leary was described as “of prepossessing countenance and built for an athlete. He stands 5 feet 9 ½ inches, and his carriage is erect. He steps with such regularity and elasticity that his movements, though quick, seem smooth. His gait is not long or swinging, but he has a short, quick hip-step, which gets him over the ground very fast.”

He reached 50 miles in 8:50:28, 100 miles in 23:01, and 200 miles in less than 50 hours. While walking, he sipped on beef tea and during his meal stops, he feasted on beefsteak, eggs, and coffee. As he dined, he was rubbed down and provided with fresh stockings and shoes.

![]()

![]()

The track was a continual problem requiring numerous efforts to drain off water, mud, and lay down more sawdust. Finally on day five, it was in such poor shape with water seeping up, that a smaller track was quickly constructed inside the first, which was thought to be eleven laps to a mile. But because this track eliminated the sharp corners of the outside track, it was discovered to be a number of feet short, requiring O’Leary to begin a walking session by walking extra laps to make up the distance. Hampered by a blistered heel, he pushed on, confident that he would succeed.

O’Leary went on to reach about 465 miles in six days and for his last miles was paced by Allcock and several other athletes. “As the final miles were announced, the wildest cheers broke forth, and when the 500th mile was called, a great shout rent the air, and it was almost impossible to keep the crowd from lifting the wonderful walker from his feet.” He finished his 500 miles in 153:02:50 hours instead of 144 hours (six days). “He showed signs of fatigue but was by no means exhausted at the close and walked the last hour at the rate of one mile in 12:32.”

He won $1,000, an elegant easy-chair, and friends presented him a medal engraved with “Champion Pedestrian of the World.” Even though O’Leary did not match Weston’s 500 miles in six days, the Chicago press proclaimed, “This feat completely eclipses humbug Weston, and shows undeniably that Chicago’s pet, O’Leary, can outlast the puffed-up Weston. Let Weston meet O’Leary, without any more nonsense, and take his punishment.” Most agreed that Weston now had a legitimate challenger and hoped that they would race against each other.

Pedestrian Fever in Chicago

Weston Also Walks for Six Days

Weston Tries to Walk for Six Days Immediately Again

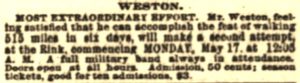

On the same day O’Leary started his walk in Chicago, Weston also started his, at 12:25 a.m. “He seemed to be cheerful and in excellent spirits, and started off briskly, with the exception of a little stiffness, which wore off gradually as he progressed in his tramp.”

Reality eventually set in on Weston. He reached 78 miles on day one, and 139 miles after two days. Foot care was a high priority, and he soaked his feet in saltwater numerous times. By the third day he looked very cheerful with a spring in his step. But on the fourth day, after only 201 miles, “he fell exhausted on the track and was carried to his room. His left leg was badly swollen from the knee to the groin.” On day five he came out for another try but quit after three miles and on the last day he was unable to walk so finally he officially withdrew. It was reported, “A red line extended from the foot to the hip and threatened the formation of an abscess. Weston was determined to go on the track again, but when made to understand that it is a question of losing the limb, if not life, he reluctantly consented to throw up the race.”

Over the ten days of both efforts, he had covered 571 miles. (Compare that to 740 running miles completed in ten days at 2019 Across the Years by Annabel Hepworth, age 47, of Castlecrag, Australia, and more than 950 miles by Yiannis Kouros of Greece, in 1988).

Reaction to Weston’s Failure and Sabbatical

![]()

![]()

The back-to-back six-day attempts apparently took their toll on Weston and he went into walking retirement for several months. St. Louis wondered, “What’s become of Weston? Has his sole stopped marching on?” In Boston: “It is said that Barnum has offered Weston $600 to walk against time. Why can’t somebody offer him $2,000 to walk against a stone wall or a buzz saw?”

William Dutcher’s Six-day Attempt

While a boy, his father died, and he was adopted by a wealthy man from Connecticut. As a teen, he ran away from home, enlisted in the army and served in the Union in the Civil War. Afterwards he returned to his mother’s home in Poughkeepsie and worked for the railroad and married Ida Scott. When he lost his job, he started his career as a Pedestrian in 1870 and accomplished the feat of walking over 100 hours. At the age of twenty-two, keeping his marriage a secret, he married a sixteen-year-old beautiful young fan, Clementina Barnhardt. He was later caught, convicted, and confined to the Albany, New York prison for three years. His poor second bride was affected so much by this that she became “a raving maniac.”

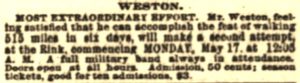

North Adams knew nothing of Dutcher’s background. He was described as “having a round, smooth face, slightly bald head, and small bright eyes. His chest is broad and deep, and his legs are very large. He has an easy, rapid stride when he walks.” It was claimed that he succeeded, reaching the 500-mile mark in five days, 23:25 in front of a packed hall of 1,000 spectators.

If true, Dutcher was only the second person in history, (Weston the first), to reach that milestone in less than six days, and he apparently beat Weston’s time by a few minutes. His handlers signed affidavits that the walk was legitimate. The gate money helped compensate Dutcher’s costs and he made immediate plans to attempt other pedestrian feats. His accomplishment was widely published across the country and surely noticed by both Weston and O’Leary.

Plans For Another Six-day Race

In August 1875, it was announced in New York City that a stock company had been formed to raise funds to hold “a grand international pedestrian tournament” for October in the city that would include a six-day race with $1,000 going to the winner. It was hoped that all the great pedestrians including Weston and O’Leary would compete.

Weston Returns

On October 16, 1875, O’Leary broke the 100-mile world walking record with a time of 18:53:40. He beat Weston’s previous mark by an hour and fifteen minutes. Using an amateur walker, John T. Ennis (1842-1829) of Chicago as a rabbit pacer, they competed in a race of sorts in the West Side Rink in Chicago. The wager was that O’Leary could reach 100 miles in less time than it took for Ennis to reach 90 miles. At 65 miles, Ennis was only five miles behind, and reached his 90 miles in an exciting finish, four minutes (one half mile) before O’Leary made his 100 miles.

Would Weston and O’Leary finally race against each other? Stay tuned for the next episode of the six-day race history.

The parts of this Six-Day Race series:

- Part 1: (1773-1870) The Birth

- Part 2: (1870-1874) Edward Payson Weston

- Part 3: (1874) P.T. Barnum – Ultrarunning Promoter

- Part 4: (1875) First Six Day Race

- Part 5: (1875) Daniel O’Leary

- Part 6: (1875) Weston vs. O’Leary

- Part 7: (1876) Weston Invades England

- Part 8: (1876) First Women’s Six-Day Race

- Part 9: (1876) Women’s Six-day Frenzy

- Part 10: (1876) Grand Walking Tournament

- Part 11: (1877) O’Leary vs Weston II

- Part 12: (1878) First Astley Belt Race

- Part 13: (1878) Second Astley Belt Race

- Part 14: (1879) Third Astley Belt Race – Part 1

- Part 15: (1879) Third Astley Belt Race – Part 2

- Part 16: (1879) Women’s International Six-Day

Sources

- P. S. Marshall, King of the Peds

- Tom Osler and Ed Dodd, Ultramarathoning: The Next Challenge

- John E Tansey, Biographical Sketch of Daniel O’Leary, Champion Pedestrian of the World

- Boston Post (Massachusetts), Nov 7, 1874, Sep 8, 1875

- The Meriden Daily Republican (Connecticut), Nov 6, 1874

- The Rutland Daily Globe (Vermont), Nov 3, 1874

- The New York Times (New York), Mar 29, May 11-21, 1875

- New York Daily Herald (New York), Mar 20, 30, Sep 12, 1875

- The Milan Republican (Missouri), Apr 2,14, 1875

- Buffalo Courier (New York), Apr 3, 1875

- Buffalo Morning Express (New York), Dec 9, 1870, Apr 3, 1875

- The Spirit of Democracy (Woodsfield, Ohio), May 11, 1875

- Pittsburgh Weekly Gazette (Pennsylvania), May 18, 1875

- The South Bend Tribune (Indiana), Apr 12, 1875

- The St. Albans Advertiser (Vermont), May 21, 1875

- Intelligencer Journal (Lancaster, Pennsylvania), May 18, 1875

- The Philadelphia Inquirer (Pennsylvania), May 22, 31, 1875

- The Indianapolis News (Indiana), May 3, 1875

- Lebanon Daily News (Pennsylvania), May 4, 1875

- Chicago Tribune (Illinois), Jul 12-14, Aug 22-23, Oct 8, Nov 12, 15, 1874, May 17-23, 30, 1875, Oct 17, 1875, Dec 24, 1876

- The Inter Ocean (Chicago, Illinois), Oct 8, May 19, 1875

- The Sun (New York City, New York), May 11-15, 1875

- The Brooklyn Union (New York), May 21, 1875

- New York Tribune (New York), May 22, 1875

- The Daily Evening Express (Lancaster, Pennsylvania), Aug 5, 1875

- The Pantagraph (Bloomington, Illinois), May 25, 1875

- St. Louis Globe-Democrat (Missouri), Jul 19, 1875

- The Berkshire County Eagle (Pittsfield, Massachusetts), Jul 22, 1875

- St. Louis Globe-Democrat (Missouri), Sep 1, 1875

- The Macon Republican (Missouri), Sep 2, 1875

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Jul 14, Sep 13, Aug 25, 1875

- The Buffalo Commercial (New York), Sep 22, 1879

- The Indianapolis News (Indiana), Aug 14, 1875

- Ulster Examiner and Northern Star (Northern Ireland), Dec 8, 1875