Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 25:27 — 29.9MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

You can read, listen, or watch

| Get Davy Crockett’s new book, Grand Canyon Rim to Rim History. Read more than a century of the history of crossing the Grand Canyon Rim to Rim. 260 pages, 400+ photos. Paperback, hardcover, Kindle, and Audible. |

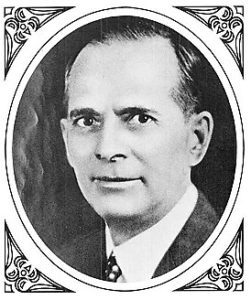

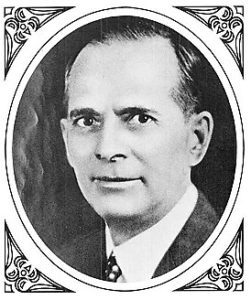

J. Cecil Alter – Weatherman Adventurer

John Cecil Alter (1879-1964) was born in Indiana in 1879, the son of a civil engineer and surveyor. He studied at Purdue University in Indiana. In 1902, he moved to Salt Lake City, Utah, taking on an assistant position in the weather bureau office which oversaw 65 stations throughout the state. He soon married Jennie Oliva Greene (1874-1949) and quickly developed into an influential pillar in the community. He became widely published with papers such as, “Agriculture in the Great Basin.” By 1905, he became a frequent contributor to the local newspapers and developed a wide following. Besides his weatherman duties, he became an editor for a monthly magazine, The Salt Lake Outlook, with interesting articles about farming, mining, and business in Utah. In 1910, he took over as section director for the weather bureau office in Salt Lake.

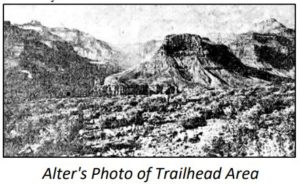

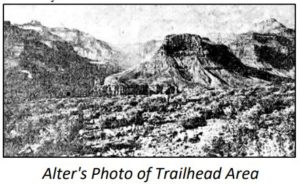

By 1913, Alter was fascinated with the automobile and became experienced driving cars to tough places. He successfully drove up a rugged canyon road to Brighton Resort in Big Cottonwood Canyon above Salt Lake City. In August 1913, he set off from Salt Lake City, hoping to reach the North Rim of the Grand Canyon in three days and be the first person to drive an automobile all the way to the rarely visited North Rim trailhead at the head of Bright Angel Canyon.

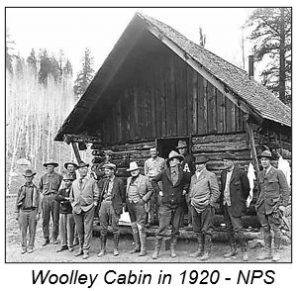

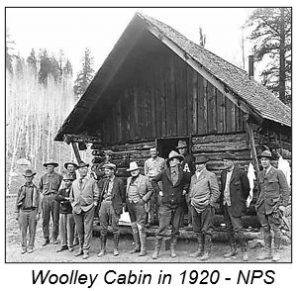

Four years earlier, in 1909, Edwin “Dee” Woolley Jr. (1846-1920) who had overseen the creation of the first trail down from the North Rim to the Colorado River took two automobiles on a round trip from Salt Lake City to his cabin on the North Rim, proving to skeptics that it was possible. He had shipped gas by horse wagon up to the Kaibab Plateau to support the vehicles, which had to receive many repairs along the way. The cars made it to within three miles of the Rim.

Alter wanted to prove that it was possible to drive all the way to the North Rim trailhead. During 1913, some rugged tourists visited the North Rim from Utah by horseback, horse wagons, and none were trying to get there in automobiles. To get there without getting lost, hired guides were needed from Woolley‘s company, because of the various networks of trails, cattle paths, and dirt roads on the Kaibab Plateau.

Alter’s journey took place in August 1913 and Utah readers were fascinated with his adventure written up in newspapers across the state. He made the successful drive to the trailhead with his wife and another couple. They then drove an additional few miles to an overlook called Greenland. He praised efforts taking place to establish a usable road to the canyon by the forest service, and believed that the views on the North Rim were better than the South Rim. He wrote, “I confidently expect that every automobile that has the courage to start will return home on its own wheels and under its own power, with as few punctures and other mishaps as could be expected in a similar mileage in almost any other direction from Salt Lake City.”

J. Cecil Alter’s 1913 Double-Crossing

Early the next morning, Alter met up with their guide, Dave Rust, to wrangle their horses in the forest. In 1906, David Dexter Rust (1874-1963) of Utah, Woolley’s son-in-law, oversaw the construction of a rough trail coming down Bright Angel Canyon from the North Rim that they referred to as Woolley Trail, now called old Bright Angel Trail, which descends steeply down into the Canyon. The trailhead is a few miles northeast of present-day North Kaibab trailhead. Rust had also established Rust Camp near the future Phantom Ranch, which served as a stopping point for those doing early rim-to-rim travel.

Mountain Lion

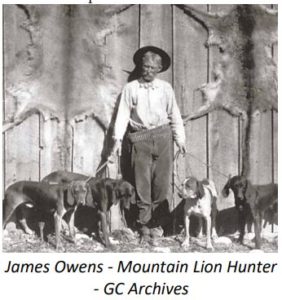

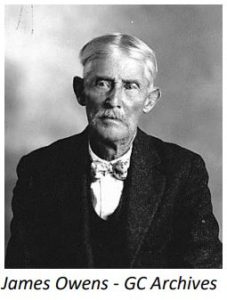

Jimmy Owens – Mountain Lion Hunter

At the North Rim, Owens was hired by cattlemen to hunt the mountain lions that were killing cattle. There were so many that at times he would earn up to $500 a day in bounties. He became known to tourists and settlers in the area as “Uncle Jimmy,” and had a large pack of hounds that he used to tree the mountain lions for the kill. “He was a familiar sight on the North Rim, often seen galloping along on his mule, preceded by a pack of hound dogs.”

Alter Company’s Descent into the Canyon

Traveling down Bright Angel Creek, wading constantly back and forth through the 96 fords was difficult, and they wished there was an actual trail to use, rather than dodging all the hidden boulders. Twilight came at 3 p.m., while they were in the Box Canyon, and they arrived at Rust Camp in the early darkness and camped for the night.

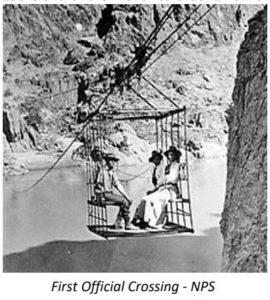

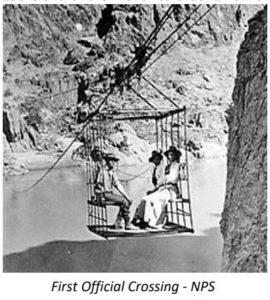

Crossing the Colorado River on the Cable Tram

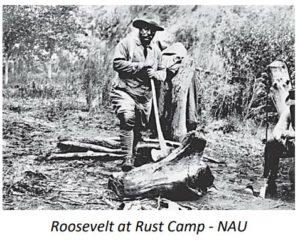

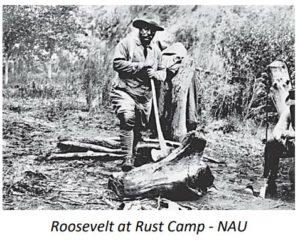

At 5 a.m. the next morning at Rust Camp, Alter woke up Dave Rust who would take Alter and his friend Jimmie over the scary cable tram that spanned the Colorado River.

Here is how the cable tram worked. The cage with passengers was moved over the chasm, first by gravity to its sagging mid-point, forty feet above the Colorado River, and then the rest of the way by using a crank attached to a large drum. If the cage was on the wrong side, the operator would go over on a narrow seat with one pulley to retrieve the car.

They arrived safely, exited, and then on foot, climbed up the zig-zagging Cable Trail that pre-dated the South Kaibab Trail. From Tip Off, they then took the Tonto Trail to Indian Garden (now name Havasupai Gardens) that Alter described as “a willow patch along a pretty creek where there are a few summer camp houses.” A prospector there gave them a cantaloupe to revive their energy.

Up to the South Rim and Back

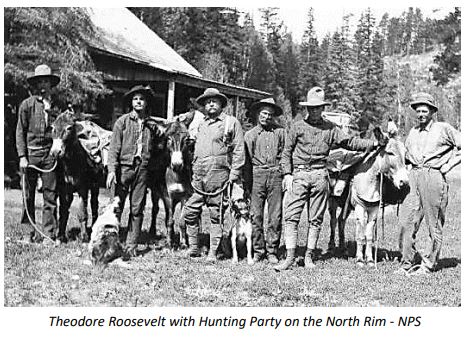

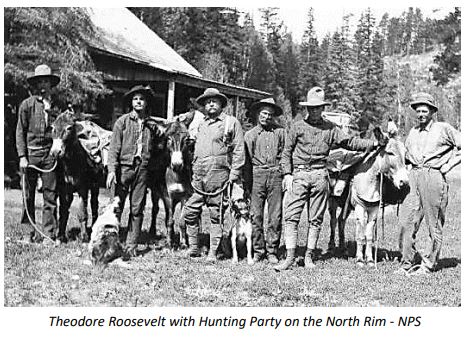

Theodore Roosevelt’s 1913 Rim-to-rim Adventure

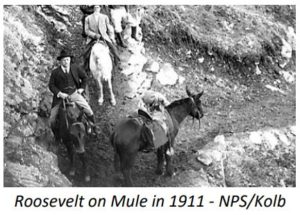

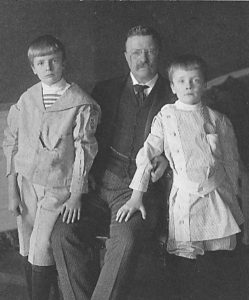

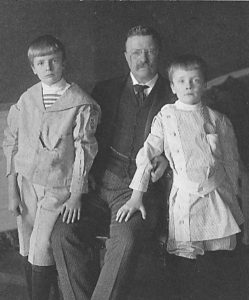

In July 1913, the former president announced that he would “hide himself from the public view for two months in the Grand Canyon, beyond the reach of reporters and out of touch with the wires.” He stated that he wanted to get away from the cares of his work and bury himself in the west. The plan was for Dave Rust and others from Woolley’s Grand Canyon Transportation Company to guide Roosevelt’s party. They were to meet him at the cable tram on the Colorado River and guide him up to the North Rim. Roosevelt and his two sons, Archibald “Archie” Bulloch Roosevelt (1894-1979) age 19, and Quentin Roosevelt (1897-1918), age 15, went down Bright Angel Trail on July 15, 1913.

When they arrived at the cable tram, no one was there to meet them as planned with horses. But cattleman, J. H. Mansfield, the superintendent of the Bar Z Cattle Company, was seen across the river and flagged down to help. He did his best to operate the trolley.

Rust, thinking that he still had a day before the party arrived, was surprised to meet the party near the trailhead. Roosevelt was angry about the mix-up and no longer wanted Rust‘s help. Will Rust said of Roosevelt, “His anger would not be appeased.”

He hired the mountain lion hunter, Jimmy Owens, and frontiersman Buffalo Jones, to guide them on their hunt for mountain lions. While at the Canyon, there was some controversy about whether Roosevelt had a proper hunting permit, but Washington D.C. quickly granted a special permit “for scientific purposes” to let his party “bag as much game as desired.”

As they journeyed on the North Rim to Woolley’s cabin, they were startled, hearing loud “war whoops” in the forest coming toward them. It turned out to be cattlemen trying to keep a herd together that had just come in contact with a mountain lion.

The company went to Owens’ cabin. “He instantly accepted us as his guest, treated us as such, and accompanied us throughout our fortnight’s stay north of the river. A kinder host and better companion in a wild country could not be found.” As they started their hunt, Owens told the party, “We’ll eat off the land – mountain lion meat and wild horse flesh.” Roosevelt found out that cougar meat was as tasty as venison.

Roosevelt observed, “A small herd of bison has been brought to the reserve; it is slowly increasing. It is privately owned, one-third of the ownership being in Uncle Jim, who handles the herd. The government should immediately buy this herd. Everything should be done to increase the number of bison on the public reservations.”

One of Roosevelt’s hunting objectives was to shoot a fabled white cougar and he carried a news clipping about the animal in his pocket. Owens commented, “I had heard that yarn before too, and of course took no stock in it.” Roosevelt asked, “There isn’t any such thing, eh?” Owens replied, “Well Colonel, I’ve been in this forest a good many years and killed a good many cougars here and seen a lot more I didn’t get, and I’ve never seen a white one.”

Roosevelt was very impressed with Owens. “Uncle Jim hunted his hounds excellently. He had neither horn nor whip; instead, he threw pebbles, with much accuracy of aim, at any recalcitrant dog—and several showed a tendency to hunt deer or coyote. ‘They think they know best and needn’t obey me unless I have a nose-bag full of rocks,’ observed Uncle Jim.”

They had some success, bagging a few mountain lions, but spent much of the time searching for their runaway horses and pack animals and trying to stop the hounds from chasing coyotes. After the trip was over, they exited north, and visited Native American reservations. Roosevelt died about five years later on January 6, 1919, just 51 days before the Grand Canyon became a national park.

Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim Series

- 46: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 1 (1890-1928)

- 47: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 2 (1928-1964)

- 48: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 3 (1964-1972)

- 49: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 4: Aiken Family

- 50: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 5: The Races

- 135: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 6: Early Guides

- 136: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 7: Prof Cureton

- 137: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 8: Kolb Brothers

- 138: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 9: Phantom Ranch

Sources:

- Frederick H. Swanson, Dave Rust: a life in the canyons, 2007

- J. Cecil Alter Biography

- J. Cecil Alter, Founding Editor of Utah Historical Quarterly

- Jim Stiles, “The President Slept Here: Theodore Roosevelt‘s 1913 Visit”

- Theodore Roosevelt, “A Cougar Hunt on the Time of the Grand Canyon”

- Dick Brown, Uncle Jim Owens – Grand Old Man of the North Rim

- Albert L. LeCount, The Grand Canyon’s Uncle Jimmy Owens

- The Salt Lake Tribune (Utah), Dec 7, 1902, Jul 20, Aug 19, 1902, Jul 22, Sep 28, Aug 26, 31, Nov 2, 1913

- Deseret News (Salt Lake City, Utah), Jan 23, 1904

- Daily Utah State Journal (Ogden, Utah), Nov 17, 1904

- The Spanish Fork Press (Utah), Dec 17, 1908

- St. Louis Post Dispatch (Missouri), Jul 16, 1913

- Salt Lake Telegram (Utah), Jul 16, 1913

- The Richfield Reaper (Utah), Sep 25, 1913

- Harrisburg Telegraph (Pennsylvania), July 19, Sept 29, 1913