Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 26:55 — 31.2MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

You can read, listen, or watch

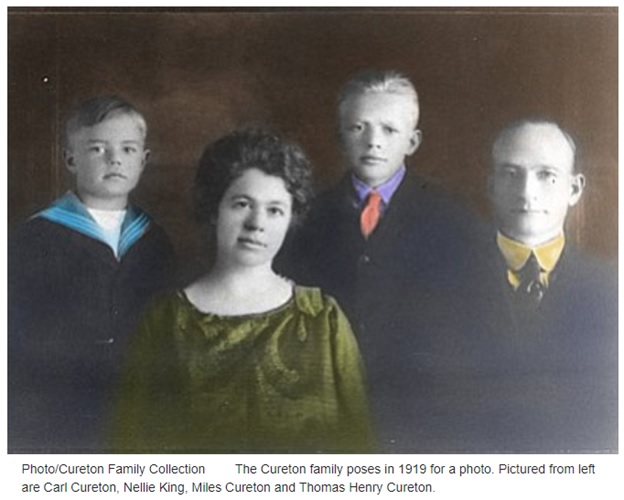

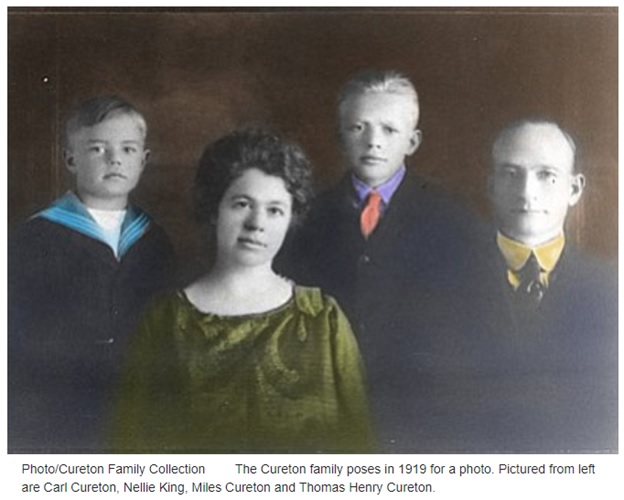

Cureton was also the grandfather of future rim-to-rim record holder, Allyn Carl Cureton (1937-2019). What led Thomas Cureton to make such an impact on the youth of Williams and to introduce them and the citizens of Williams to the joy of crossing the Grand Canyon rim to rim?

| Get Davy Crockett’s new book, Grand Canyon Rim to Rim History. Read more than a century of the history of crossing the Grand Canyon Rim to Rim. 260 pages, 400+ photos. Paperback, hardcover, Kindle, and Audible. |

Superintendent of Schools in Williams, Arizona

Cureton was originally from Missouri. He started teaching in 1894 in a country school near Neals, Missouri and then moved to Montana, where he taught for several years. Furthering his education, he moved to Lawrence, Kansas, and received a law degree at the University of Kansas. While attending, he married Nellie May King (1880-1960), of his home state of Missouri. She also attended Kansas, where she received a master’s degree in Latin. Both were highly educated and natural leaders.

In 1906, they moved to Williams, Arizona, where Cureton became the superintendent of schools. He was given the title/nickname of “Professor” or “Prof.” Teaching conditions were challenging in the small city, with about 1,000 residents. The school, grades 1-8, were crowded with up to 200 children, 50 per room, in the four-room school where Cureton was both the principal and teacher of multiple grades. The school was built in 1894 and expanded in 1900. During his first year there, another needed addition was built onto the school, expanding the classrooms, completed in 1907.

After two years, in 1908, Cureton resigned his job in Williams to take a “more lucrative position” in Guanajuato, Mexico. After a year, he went back to school and attended Harvard University, where he earned a Master of Arts degree.

Return to Williams

Attendance at the school dramatically increased. Cureton soon introduced an athletic club at the school. He was a strong advocate of sports, especially basketball. While attending the University of Kansas, he had become acquainted with its physical education director, Dr. James Naismith (1861-1939), who invented the sport of basketball in 1891.

School Burns Down

Early in 1912, as the school children were still on winter break, the Williams School building burned down. “One cold day in January 1912, Williams was awakened at 6 a.m. by the loud pealing of bells and the shrill blowing of whistles. The leaping flames to the south, with telegraphic swiftness, announced to the remotest sections of town that the schoolhouse was on fire and that no possible force within reach could save it. The peal of the old school bell is hushed and its tongue choked with fire and ashes beneath a debris of fallen walls.” The suspected cause was sparks from a chimney fire. Pipes were frozen, making it impossible to save the building. Cureton worked hard to save the school year. What little furniture that could be saved was moved into the Methodist and Catholic churches and the upstairs of the opera house to continue classes. In the fire, he lost all his class notes from Harvard, along with many books. Thanks to his lobbying efforts, within a month of its burning, a larger school was planned to be built. The new school was completed in only eight months, ready for the next school year. The first high school in Williams was also established with only a few students, but it would grow to 47 in 1921.

Cureton’s Community Service and Government Service

In 1913, he became the president of Williams Chamber of Commerce. The Williams News wrote, “Mr. Cureton has done as much as any other one man toward the building up and improvement of this growing city. He is a strong believer in the best of education facilities for children and is a man of experience and judgement in this department.” Cureton started to purchase acres of land in Williams, becoming one of the largest property owners in the town. He branched out into a business building bungalows and cottages around town and sold alfalfa hay to local farmers, and also established a poultry ranch selling eggs and chickens.

Cureton became more involved in politics and in 1916 he ran for the country representative in the state house of representatives with the slogan, “Fewer and Better Laws.” He won, but also continued as the school principal. Near the end of his two-year term, he agreed to run for the state senate. It was reported, “He wears a hat with a modest brim and does not cater to the movies.” He lost by only 200 votes.

Involvement in Sports

In 1918, the Spanish flu hit the city hard. Cureton closed schools for six weeks during the Fall of 1918 and the pandemic resulted in a teacher shortage in 1919. Cureton was deeply involved with his students, even after school hours. In 1919, he had arranged a basketball game between the high school team in Williams against the team in Winslow, Arizona. The boys were allowed to travel to the game without adult supervision. The Williams team won convincingly but behaved poorly during the game. “A very unpleasant incident occurred during the game compelling the officers to penalize the visitors for use of profane language which was objected to by some of the spectators.” Cureton wrote a long letter of apology to the Winslow schools. “Never again will I allow schoolboys to go alone even though our games go far behind financially. I have had the boys in my office a long period today and they all regret the conduct and promise to be gentlemen in the future.”

Outdoor Camping

In July 1921, Cureton started taking youth on campouts, which would eventually lead him to the Grand Canyon. He took boy scouts camping out in the forest at Sycamore Canyon, about 17 miles from Williams. The attraction was a swimming hole with cliffs to jump off. Cureton always camped with a minimalist approach, sleeping out in the open with just blankets. After a day of swimming, the boy’s only clothes were wet. At night, Cureton told them to undress, sleep in their blankets, and when they became cold, to get up, put on their wet clothes and get dried off in front of a bonfire. A favorite activity during the day was “chipmunk races.” “Someone would spy a chipmunk and off they would all race through the woods ‘till someone ran him up a tree. When he jumped, the lucky fellow catching him was the winner. They would then set him free, the excited chipmunk no doubt wondering what all the hullabaloo was about, but thankful for his skin.”

Nellie Cureton

In 1922, Cureton’s wife, Nellie, was elected the state president for the Federation of Women’s clubs. For years she had been active in woman’s clubs, as well as the education life of Williams. She would become more famous state-wide than her husband, traveling to speaking engagements. She said, “Every woman will understand what it means to be a wife, and the mother of two growing boys. Sometimes, when I’ve been away from home for two or three days, I get a rather guilty feeling about my home, but when I go back and see how smoothly everything has been going, I get over it right away.”

In 1923, the respect that students had for Prof Cureton was on display when the Seniors observed “ditch day,” and kidnapped Cureton to join them on an outing to view cliff dwellings near Flagstaff. “Prof felt proud of the students who did not idly waste their time but showed such keen interest in the formations, art and history of the ancient landmark, that he was called upon to do as much lecturing as any school class demanded.”

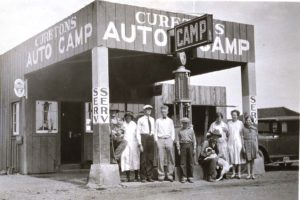

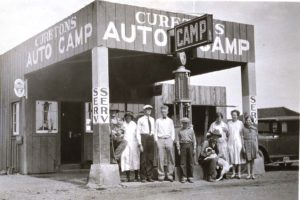

Cureton’s Auto Camp

Cureton had a vision for Williams. He was very active in the Rotary Club meetings, speaking often. At one meeting, he heard a visitor ask, “Why do you live in this little old hole.” Cureton spoke up and said, “We love the mountains and the pines. Furthermore, we know that Williams has a future. Someday thousands of people will come to our mountains to cool off beneath the pines in summer and snow sports will draw others in the winter. Williams will become a thriving little city of 3,000 souls. We live here because we like the ‘little hole.’” In 2021, the population of Williams was 3,265, and it was called “The gateway to the Grand Canyon.”

Extreme Hiking

During the summer of 1924, together with Clarence E. Ratcliffe (1882-), a photographer, he made a very rugged five-day hike down Sycamore Canyon, the second largest canyon in Arizona, head to mouth, about 40 miles, in the heat of August when water was scarce. They each carried about 30 pounds and had to continually search for water in stagnant pools. Thanks to a rain shower, they avoided severe dehydration. “These men are possessed of what might be termed a peculiar bent, in that they are the only ones known to have been similarly inflicted for many, many years.” Cureton became hooked on doing tough long-distance hikes.

1924 Grand Canyon Youth Hike

Cureton, age 48, led his first Grand Canyon rim-to-rim hike during the week of August 17, 1924, taking four young men from Williams with him. Ratcliffe, the photographer, also went along. The hike was ambitious, four days total, camping at the bottom each way. The four young men were Edward “Eddie” Martin Hoffemeyer (1909-1987), age 17, Jeremiah “Jerry” Wayne Duffield (1906-1984), age 17, Charles “Charley” Robert Way (1906-1976), age 17, and Burns Alvero MacLean (1903-1977), age 20.

They made stops to enjoy the scenery and also for swims in the Colorado River. “The ascent to the North Rim follows the bed of Bright Angel Creek for four miles and this creek is crossed sixty times in that distance. At first the party took off their shoes before crossing, but later they saw the impossibility of keeping this up at each ford and plunged in full-shod. The stream is about 18 inches deep and very swift.” They carried very little food, mostly bread and bacon and got quite hungry. “The trip was enjoyed as keenly by Prof as by the boys. Prof looked ten years younger after the fine outing.”

1925 Young Women’s Double Crossing

In 1925, Cureton again brought a youth group to the Grand Canyon to experience a double crossing and to camp in rugged open-air conditions. The group that started down Bright Angel Trail on June 14, 1925, consisted of seven young women, three ladies, and three men. They had planned for a ten-day double-crossing on foot. The young women were: Bernice Easton (1908-1959), age 18, Helen Easton (1906-), age 20, Catherine Miller (1909-1963), age 19, Doris Duffield (1909-1992), age 17, Helen Rounseville (1910-1981), age 16, Joyce MacLean (1908-1992), age 18, and Nieves Gonzales (1906-1942), age 20. The ladies were: Annie Jaggard, Minnie Watson, and Mrs. Angus. The men were: Dick Cole, Ralph MacLean (1899-1961), and Prof Cureton. “The party consisted of that so-called unlucky number of thirteen but some of them claimed that they were going to pick up a black cat to make up for the unlucky number of persons in the party.”

On the first day, they descended 3,000 feet and seven miles, passing through Indian Garden (Havasupai Gardens). They continued for a couple of miles and stopped on the Tonto Trail. “After supper, we spread our blankets in the sand and gravel for our first night out. The girls sang us to sleep.”

The next morning, after a breakfast of cream of wheat, bacon, bread and prunes, they continued east to Tip Off. They hiked down the nearly complete new South Kaibab Trail and crossed over the Swinging Suspension Bridge, which gave them a thrill. Their second camp was above Phantom Ranch before The Box. “The temperature was fierce. We all took a plunge in Bright Angel Creek.”

Good improvements had not yet been completed up Bright Angel Creek, so the next section of their hike was the toughest. They had to wade across the creek 37 times in two miles. “The water was cold and swift and in places two feet deep with round rolling, slick boulders on the bottom. But every member of the party was equal to the task and came through in good shape.” They camped near Ribbon Falls, where they played the next morning. The following night, they camped under some oak trees along Bright Angel Creek above the confluence with Roaring Springs Creek.

On their return trip, Cureton killed a large rattlesnake near Ribbon Falls, but didn’t tell the girls until the next day, for fear that they would not be able to sleep that night. On the next day, Cureton took them up to view some cliff dwellings. The rest of their journey went well, and they successfully reached the South Rim where their cars were waiting for them. “The nine-day trip camping in the open will long be remembered by every member of the party.”

1925 Young Men’s Double Crossing

On their return journey the next day, they made good time and reached the river by early afternoon. “They spent the day in throwing contests and blanket tossing.” While heading up to the South Rim on the Tonto Platform the following day, they killed a rattlesnake and camped at Indian Garden. Before noon, the next morning, they arrived at the top and gave a huge ovation and cheers to Cureton, showing their appreciation for the wonderful trip. “There were no sad incidents except a few blisters.”

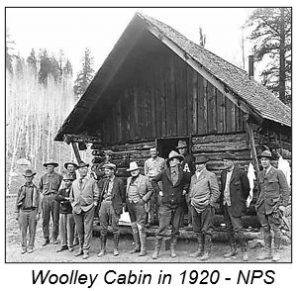

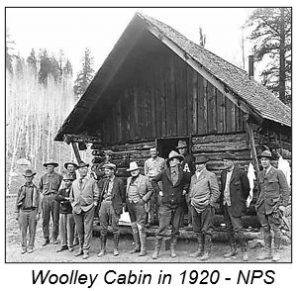

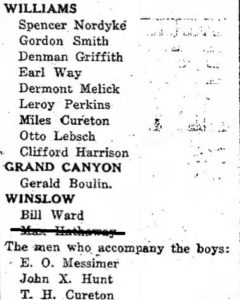

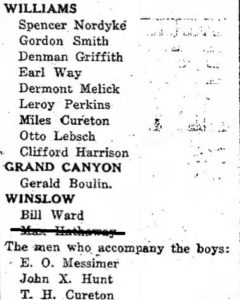

1926 Young Men’s Double Crossing

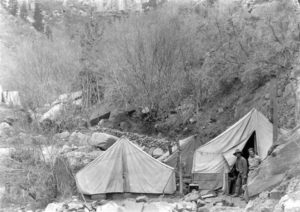

![]()

![]()

It was quite cold that night, but they stayed comfortably warm in the pine needles and kept a big campfire blazing throughout the night. “One of the pine needle beds caught fire from the sparks about midnight, furnishing yet another variety of thrill. After extinguishing the blaze, the crowd wrapped themselves in their blankets and lay as close as possible to the fire until dawn.”

They had originally planned to camp for two nights on the Rim but because of the cold and wind, headed back across the Canyon on the next day and caught many large rainbow trout in the creek along the way. They had to move their camp for the night after being driven out by scorpions. “The journey enlivened by almost constant singing, the favorite selections being ‘A Long, Long Trail’ and ‘The King of the Cannibal Islands.’ The boys found it very interesting to listen to the various echoes along the trail and compare the number discernible at different points.”

Principal in Maine, Arizona

That year, Cureton made an unsuccessful bid to again be elected to the Arizona House of Representatives. After nine years as superintendent of Williams schools, in 1927, he became principal of Maine schools, east of Williams. He still maintained his home and businesses in Williams.

In 1928, his wife became critically ill and was sent to Phoenix to spend many weeks in the hospital. She ended up staying in Phoenix recovering for months and son Carl went there to attend high school and care for his mother. She would recover and live to be 80 years old.

1928 Double Crossing Hike

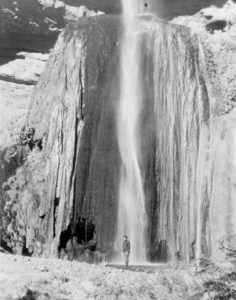

![]()

![]()

The group camped for the night on the “Little Sahara” beach. “We all went wading and the boys later in the evening went swimming. After supper (oatmeal, raisins, prunes, coffee, and bread) we played in the soft silver sands for a while, then since we were all tired, we unrolled our blankets and tried to sleep. A hot breeze blew sand in our faces all night. None of us were used to sleeping on the hard ground, so I am afraid none of us got much sleep that night.”

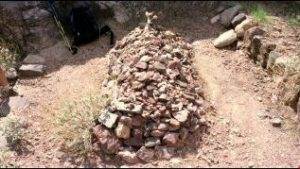

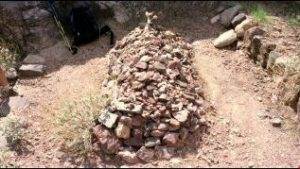

In the morning, Cureton took the youths to the grave of Rees Griffiths (1872-1922) who had died only a few years earlier working on the trail along the north side of the Colorado River. “He was buried in a niche in the granite wall and a border of beautifully colored rocks of the Grand Canyon was placed around the grave. A plate with his name and other information about his death was cemented in the wall over the grave.”

Their stroll through Phantom Ranch was amazing. “There was a lovely orchard here, and we all gazed hungrily at the peaches and apples hanging on the trees. Carl and Leslie dropped behind and from the smiles on their faces when they again joined us, we knew that the peaches were good. Prof played some more tunes as we continued our march.” They continued up through The Box and reached Ribbon Falls in the late afternoon, where they stashed some food for the return trip in the cliffs near the falls. “There was a cave under the falls and we all waded back into it. We got very wet passing under the falling water, but we didn’t mind that.” As they continued, Cureton killed a rattlesnake, and they camped under Roaring Springs, where there was a stove and the remains of a construction camp. “That evening, we told ghost stories after our blankets were spread out and supper was over. It rained a little that night but didn’t bother us. A deer came into camp and woke us up.”

On the hard climb up the North Kaibab Trail, still under construction in Roaring Springs Canyon, one girl was so exhausted that the boys carried her up quite a distance. At the North Rim, they resupplied their food at the nearly complete new Grand Canyon Lodge. Because Cureton knew the manager, they were allowed to look all around the hotel, and “almost bought the soda fountain out.” After fully supplied, they headed back down the trail, camped again at Roaring Springs, and the boys went fishing.

At about noon the next day, they had company at their camp. “A guide came down to our camp. There were just two women in his party, two ladies from Boston and neither had ever been on a mule before, so you can imagine how sore and stiff they were. They had on dresses and little silk hats. Their faces were burned fiery red, and they were exhausted and uncomfortable. The guide helped them from the mules to the cool shade under the trees. We talked to them and after they had eaten their lunch, which the guide carried on his saddle, they went on to the river.”

That evening, they ate fish and played games. “We found some boards and fixed up a seesaw on a rock and took turns bouncing up and down. Then we pitched half dollars into holes in the ground. We played until we were tired. We told ghost stories that night, then went to sleep.”

The next day, they reached Ribbon Falls, where they retrieved their stash of food. “We got into a water fight. The rest of the gang was plenty wet too.” They went back to work hiking, ate supper at Phantom Ranch, and then camped at the Colorado River. “The boys built a big fire on the sand, and we had a time telling stories, then went to sleep thinking of the hard climb the next day.”

In the morning, they climbed up to Tip Off and then took the Tonto Trail toward Indian Garden. “We camped at Burro Springs where Prof told us we could cook anything we wanted – cooked fruit, millions of hot cakes, and something of nearly everything we had, then we ate! The sun went behind the clouds and it stormed fiercely for a while, then the sky cleared and we marched on to the Indian Garden in the late afternoon. There were lots of fruit on the trees here and we ate plenty of green and ripe ones too, peaches and apples.”

They got up at 3 a.m. to get ready for the last climb. “We went slowly and rested often and gradually drew nearer the top. We met many people coming down the trail afoot and by muleback.” They reached the top and ate everything in their packs. This was the last known youth double crossing that Cureton led. Over the years, he brought nearly 50 young people rim to rim and back. His pioneer rim-to-rim efforts inspired and launched hikes involving thousands of boy scouts to hike rim-to-rim in the decades to come.

Concluding Years

In 1929, Cureton had an unusual attraction at his auto camp in Williams. “He has two beautiful mountain lions imprisoned in a cage near the camp. Both are thriving in captivity and furnish much amusement for those stopping at the camp.” He served in the state house of representatives for another term and then took a teaching job in the small very rural town of Wickieup, south of Kingman, Arizona, but still maintained his businesses in Williams.

Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim Series

- 46: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 1 (1890-1928)

- 47: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 2 (1928-1964)

- 48: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 3 (1964-1972)

- 49: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 4: Aiken Family

- 50: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 5: The Races

- 135: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 6: Early Guides

- 136: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 7: Prof Cureton

- 137: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 8: Kolb Brothers

- 138: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 9: Phantom Ranch

Sources:

- Williams News (Arizona), Aug 15, 1908, Oct 2, 1909, Sep 2, Oct 21, 1911, Jan 6, 12, Feb 10, Mar 23, Apr 6, Jul 27, Oct 12, 1912, Jul 12, Sep 4, 1913, Nov 7, Dec 18, 1913, Jun 7, Dec 20, 1918, Jan 31, 1919, Aug 5, Dec 9, 1921, Apr 20, 1923, Jan 25, May 30, 1924, Aug 8, 22, 1924, Jun 19, 26, Jul 3, Aug 21, Sept 4, Nov 12, 1925, Jan 21, Dec 2, 1927, Jul 20, Sep 7, 1928, Jan 11, 1829, Jun 28, 1935, Jul 7, 1938, Feb 8, 1940, Oct 20, 1955

- The Coconino Sun (Arizona), Jan 5, 1912, Oct 20, 1916, Sep 4, 1925, Jul 16, Aug 27, Sep 3, 1926, Apr 8, 1927

- Arizona Republic (Phoenix, Arizona), Aug 25, 1912, Apr 16, Oct 26, 1922

- Bisbee Daily Review (Arizona), Nov 19, 1918

- Winslow Daily Mail (Arizona), Nov 28, 1919

- The Leader-Post (Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada), Jul 29, 1929