Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 30:46 — 38.1MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

This is the third part of the rim-to-rim series. Read first Part 1 and Part 2

As the Grand Canyon entered the 1940s, the corridor trails were in place along with the Black Bridge across the Colorado River, making rim-to-rim travel on foot possible. By the early 1960s, a few daring athletes were hiking or running rim to rim in a day and even a few completing double crossings in a day. Credit goes to Pete Cowgill (1925-2019) and his Southern Arizona Hiking Club from Tucson, Arizona, who demonstrated to all that crossing the Canyon on foot in a day was not only possible but was an amazing adventure.

As the Grand Canyon entered the 1940s, the corridor trails were in place along with the Black Bridge across the Colorado River, making rim-to-rim travel on foot possible. By the early 1960s, a few daring athletes were hiking or running rim to rim in a day and even a few completing double crossings in a day. Credit goes to Pete Cowgill (1925-2019) and his Southern Arizona Hiking Club from Tucson, Arizona, who demonstrated to all that crossing the Canyon on foot in a day was not only possible but was an amazing adventure.

The Boy Scouts in Arizona started to offer rim-to-rim patches to those who completed the hike. A rim-to-rim-to-rim patch appeared in 1963. Publicity for the patches were being published in national scouting magazines. That year a fifty-mile hike craze was also burning throughout the country attracting more hikers to the Canyon. Arizona State College in Flagstaff started to organize large rim-to-river and back hikes.

Warnings were offered by the wise: “It is more rugged than anything you have every pictured. Despite its famed beauty, the canyon is a natural killer and hardly a year goes by that it doesn’t claim at least one life in some way.”

In 1963, visitors topped 1.5 million and serious growing pains were felt at Grand Canyon Village with traffic, crowded lodging, and strained Park services. More development was needed but the big limitation was water. The quest for water would result pausing in rim-to-rim travel for more than five years.

The Trans-Canyon Water Pipeline

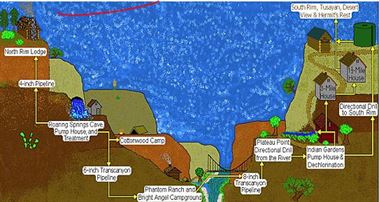

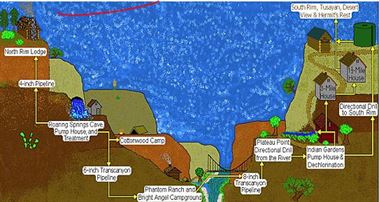

South Rim

Obtaining water for both Grand Canyon rims has always been a challenge. Since before 1900, on the South Rim, water was hauled in from 18 miles or more. By 1919, the Santa Fe railroad hauled up to 100,000 gallons per day to Grand Canyon Village. In 1926 a reclamation plant was built to reclaim water for non-drinking uses which helped some. Deep wells did not exist because of all the sedimentary rock layers. Rainwater would just run out of the rock and down into the Canyon.

In 1931 construction of a water system began at Indian Garden to pump water up to the South Rim. A cable tramway was constructed from the rim to about a mile above the Garden which was used to bring down a five-ton tractor to help with construction. The tram was removed in 1932 but signs of it still be seen 50 yards northeast of the 3-mile rest house. By 1934, the pump was in operation bringing about 150,000 gallons per day 3,200 feet up a six-inch pipe to the South Rim. The water was still supplemented during the summer with water tank train cars and million-gallon storage tanks. Portions of this pipeline are still visible.

North Rim

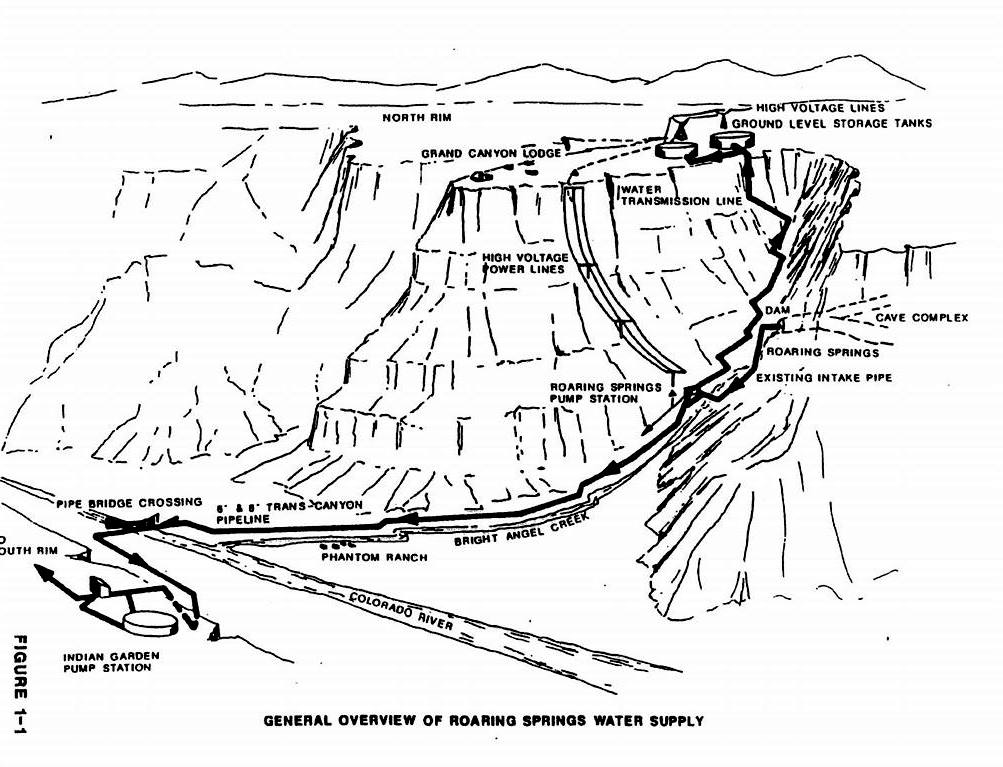

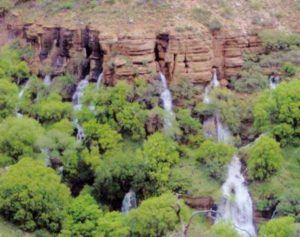

With all the visitors coming to the North Rim, the few springs near the top did not provide enough water. By 1928 a power plant was built below Roaring Springs to generate power for a pumping station to lift water 3,870 feet to the rim through 12,700 feet of three-inch steel pipe, some of which can still be seen today. The heavy machinery to construct the plant and pump station was lowered on the tramway that had been built to bring material down to build the North Kaibab Trail.

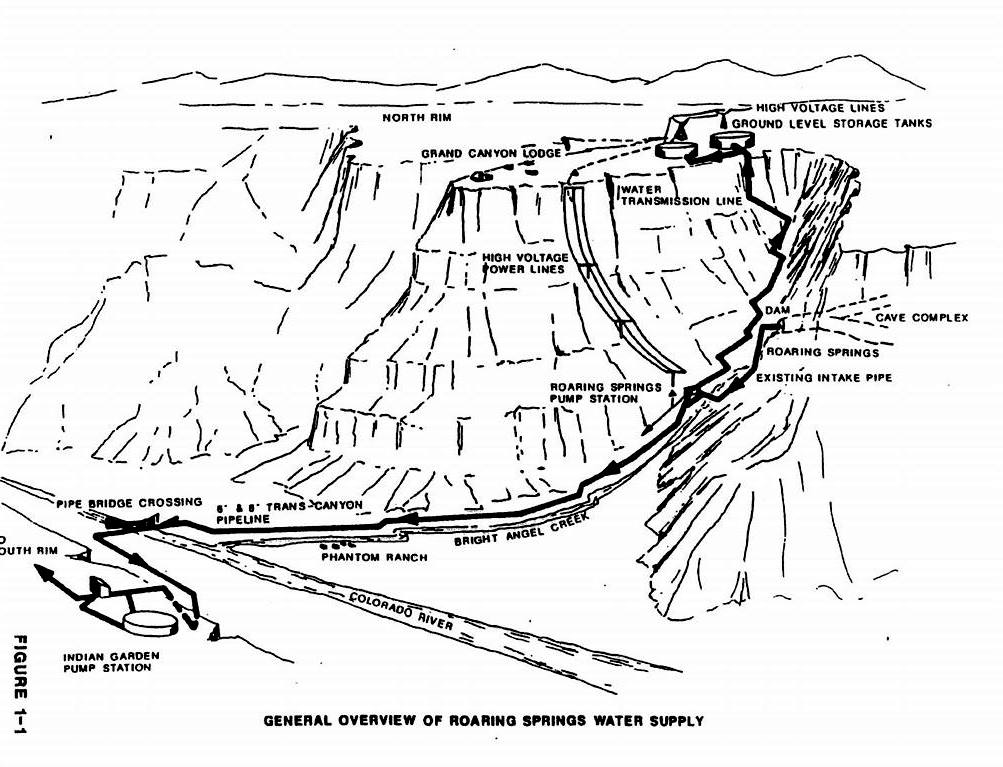

Plans for the trans-canyon pipeline

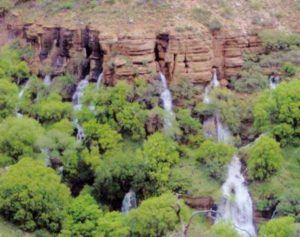

The cave’s average flow of water is 5.8 million gallons per day. The plan was for seventeen percent of the spring water to be diverted into two intake pipes. The rest of the water would free-flow out the east cave entrance down to Roaring Springs Creek. At the Roaring Springs pump house, sediment would be removed, and chlorine gas is used to purify the water. Some water would be pumped up to the North Rim and up to 500,000 gallons of water per day travel by gravity all the way to a tank at Indian Garden on the south side of the Colorado River. At times not to disturb visitors, the Indian Garden pumps would push the water the rest of the way up to the South Rim to storage tanks.

“The pipeline must be laid under a three-foot-wide horse trail. Strict rules to preserve the beauty and natural scenery of the canyon specify that no plant or rock outside the trail can be disturbed. And when the job is finished the hikers and mule riders should be able to travel the trail without knowing the pipeline is there.”

Construction begins

A $2,277,557 contract was awarded to the Halvorson-Lents Construction company of Seattle, Washington, a company that had developed the reputation of undertaking risking jobs few other would even consider taking on. The construction was led by Elling Halvorson, age 33. The company had recently built a communications facility in the Sierra, well above Echo Summit Pass, high above Lake Tahoe. Halvorson did extensive exploring along the route designed by the Park service and successfully won a low, but realistic bid for the work. He moved his wife and six children to Grand Canyon Village.

The park announced that North Kaibab Trail would be closed during the construction. “The closure has been found necessary because of the extremely hazardous conditions prevailing during the present phase of construction between Roaring Springs and Phantom Ranch. Large section of the trail must be excavated.”

Digging ditches

Construction men called it one of the most difficult pipeline jobs every undertaken because big machinery could not be used. Special small machinery that could fit on the six-foot-wide trail needed to be used. One was a crawler-type tractor with a mounted compressor and 1.5 inch drill. Most of the 18-inch ditches for the pipeline needed to be blasted out of solid rock. Dwarf backhoes, a tiny bulldozer and a rock crusher mounted on a Jeep chassis were used.

“With the tiny backhoe, the loosened rock and dirt is dug out and loaded onto a conveyor that carries it to a small crusher that reduces it to about one-inch size. This crushed material then is dropped back into the trench, filling it so that foot traffic and vehicles can move over the trail until it is time to lay the pipe. Dirt or crushed material cannot be piled outside the trail under the no-disturbance rules.” .

Laying pipes

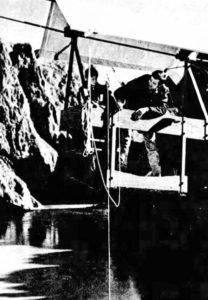

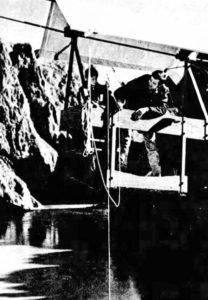

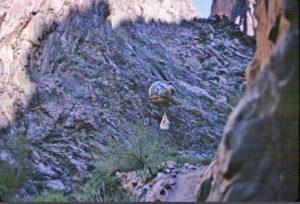

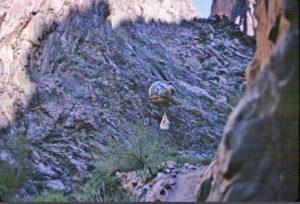

Helicopters carried in the welding equipment and crew. Fifty-foot lengths of aluminum pipe were carried, two at a time under the helicopters from a staging area at the head of Kaibab Trail on the South Rim. Twists and turns happened about every 12 feet along the pipeline route so the bending station operated daily at Plateau Point on the 50-foot pipe segments. Measurements for the bends were sent up two days in advance. They used aluminum pipe because it was easier to bend.

Helicopters brought down all the materials to various staging locations along the North Kaibab Trail, River Trail, Plateau Point Trail, and Bright Angel Trail. It was said to be a spectacular thing to watch.

When it came time to lay the pipe, they were welded into place, and a small backhoe moved in and cleaned out the crushed material.

Hiking during construction

In February 1966 the Park announced closure to trails for at least six months. Bright Angel Trail was open to Indian Garden, but the Plateau Point Trail was closed. The River Trail was closed and also the North Kaibab Trail through The Box. Rim to Rim hikes were not allowed.

Silver Bridge

By December 1966 the pipeline and Silver Bridge neared completion and were awaiting inspection.

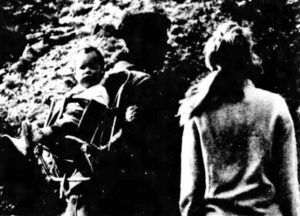

The Burnetts

The Brunetts were still living in the canyon three years later, in 1966. Their only permanent neighbor was Ken Smith, a Park Service employee who maintained the trails and campground. Three-year-old Miggy would play outside the house watching deer, squirrels, mice, and the passing mules. The little boy would also greet hikers who came by. On summer nights the Burnetts would lie on cots outside and enjoy the stars. The Burdett said that they “much prefer the sounds and the fragrance of the outdoors to the clatter of traffic and the gas fumes of city streets.”

With the pipeline work going on, helicopters were frequent and would land a little downriver. “The workmen know Miggy and give him rides on their machines or scooters.” They would reach into their lunches to give him a cookie or an orange. Miggy would play with a toy helicopter of his own. In 2020, Bill Burnett was 83 and living in Sedona, Arizona.

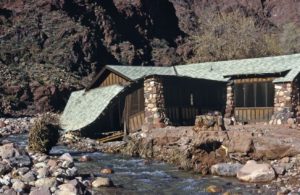

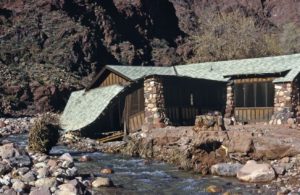

1966 Flood

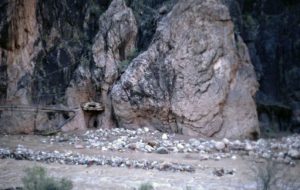

The flood struck Phantom Ranch “with the noise of a dozen locomotives” heard by the employee of the U.S. Geological Survey who lived at Phantom Ranch. He feared for his life and explained, “The big boulders that are in the bottom of the canyon must all be touching one another. The vibration of the flood was transmitted through them, and the ground itself trembles under your feet. It wasn’t just the size of the flood, but the duration of it. It rose up and didn’t drop an inch for three days.” Phantom Ranch became isolated, leaving a few people who were there marooned for several days until the floodwater subsided.

The flood washed away restrooms, the sewer system and various other structures that had stood for nearly 60 years. Bright Angel Canyon and many of its tributaries were now ten feet deeper than before the flood. Boulders weighing up to six tons, earth, and rocks slid down the Canyon cliffs. It caused an estimated $2 million in damage.

The aftermath

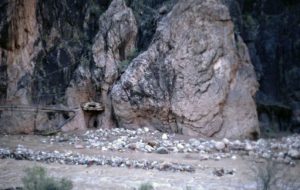

The crash

A week later, on December 12, Halvorson returned with a couple managers to assess the damage more closely. They took off from Yaki Point flew to the mouth of Bright Angel Creek at the Colorado River. He said, “I saw the exhaust stack of a Caterpillar crawler tractor sticking up from the water like a periscope. It had tumbled downstream about one and a half miles.” They landed to examine it. He noticed that cottonwood trees that had been as tall as a 10-story buildings had been swept away.

They lifted off and he told the pilot to fly low and slow so they could photograph the damage. He wrote, “We few 40 miles an hour at 75 to 100 feet above the canyon floor. Suddenly we slammed into an antenna wire, formerly hidden by cottonwood branches, that had been put there by the Civilian Conservation Corps. The wire snapped and whipped around the helicopter. The pilot tried to land but the wire ripped off the tail rotor and blades.” They spun out of control and crashed on the rocky shore below.

Halvorson was seriously injured and thought he was dying. The others received only minor injuries. The U.S. Geological Survey employee witnessed and even filmed the crash. He rushed to his house only 100 yards from the crash and telephoned the South Rim for help. Another helicopter rushed down and took Halvorson to the hospital. His entire chest had been crushed with 18 broken ribs. He also had a punctured lung, and a broken leg. He needed to be taken to the hospital in Flagstaff, but no ambulance was available, so he was transported in a hearse bearing the name “Flagstaff Mortuary” on the back. He quickly recovered and was walking again in two weeks.

Reconstruction

In April, 1968, an agreement was finally reached for the Park to provide $1.6 million of additional funds to complete the pipeline. Work started up again in August 1968. North Kaibab trail was still closed. Thirty-five men were flown in and out of the canyon by helicopters. Because most of the original North Kaibab trail had been swept away in Bright Angel Canyon, they could rebuild a much safer trail and did not have the same restrictions for skinny machines. They also didn’t need to crush rock, there was plenty in the stream bed.

Construction this time was more serious and sturdier, taking more time. A bulldozer, front-end loader, three tractors, several dump trucks, ten pickup trucks, and a large trailer-mounted air compressor were used to dig trenches, bury the pipe, and smooth out the new trail. Workers were moved up and down the trail on motorcycles. Design changes were made to lift the pipeline and trail higher along Bright Angel Creek in The Box and near Cottonwood Campground.

More Deaths

Earlier in October, three pipeline workers were injured when their helicopter crashed on takeoff at Yaki Point. On average, three helicopters were in constant use each day for six hours. Through all the years of pipeline construction, seven men were killed in crashes.

Bright Angel Creek Bridge Construction

The crew also relocated Bright Angel Creek in certain places, especially near Phantom Ranch. Gabion baskets with wire mesh around rocks were used to prevent erosion, still seen today.

Pipeline Completion

The pipeline was put into operation and was capable of delivering up to 500,000 gallons of water to the South Rim per day. This was equivalent of more than 20 railroad tank cars. It was written, “The thirst of Grand Canyon has been quenched.”

pipe bends through The Box.”

There were a few minor breaks in the line from rockslides. In July 1971, a wall of water again rushed down Bright Angel Creek and stranded hikers from Phantom Ranch on the wrong side of a washout area. They had to spend the night out in the canyon. Rangers came to the rescue the next day, strung ropes across the rain-swollen creek, and helped the hikers on their way. The washout exposed a 60-foot section of the water line about a mile above Phantom Ranch.

The most serious problem was in 1973 when there was a large amount sediment in the water at Roaring Springs because of a heavy runoff year. The pumps could not run at full capacity because of the silt that caused the units to overheat. Water needed to be recirculated to slow the flow down. Normally 480 gallons per minute would flow but it was reduced to 140 and the South Rim experienced a water shortage during the summer.

Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim Series

- 46: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 1 (1890-1928)

- 47: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 2 (1928-1964)

- 48: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 3 (1964-1972)

- 49: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 4: Aiken Family

- 50: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 5: The Races

- 135: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 6: Early Guides

- 136: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 7: Prof Cureton

- 137: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 8: Kolb Brothers

- 138: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 9: Phantom Ranch

Sources:

- Martha McKee Krueger, Bobby, Brighty, and the Wylie Way

- Arizona Republic (Phoenix, Arizona), Jul 17, 1963, Aug 9, 1965, Feb 22, 27, Apr 13, Dec 8, 17, 1966, Jan 20, Apr 19, May 28, 1967, Aug 5, 1969, Jul 25, 1970, Jun 19, 1973

- Arizona Daily Sun (Flagstaff, Arizona), Jun 27, 1963, Dec 15, 1966, May 23, 1968, Nov 24, 1968, Jun 30, 1969, Dec 16, 1969, Jun 11, 2008, Feb 9 2009

- Arizona Daily Star (Tucson, Arizona), June 10, 1960, June 18, 1961, Jun 21, 1964, , Jul 24, 1970, May 19, 1979, May 4, 1990, Jun 28, 1992, Dec 6, 2007

- Statesman Journal (Salem, Oregon), Aug 8, 1965

- Tucson Daily Citizen (Arizona), Jul 27, 1966, Jul 28, 1970, Jul 21 1971

- Michael P. Ghiglieri and Thomas M. Myers, Over the Edge: Death in the Grand Canyon

- Halvorson, Elling. Detours to Destiny: A Memoir

- Wayne Ranney, “Early Musings”

- Trans-Canyon Water Pipeline