Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 27:05 — 31.9MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

His pioneer 1976 24-hour run in New Jersey brought renewed focus on the 24-hour run in America. He won multiple national championships and was inducted into the Road Runners Club of America Hall of Fame. During his running career, he ran in more than 2,100 races of various distances.

Of his youth, Osler said, “I was a sickly little kid at 12 or 13 and didn’t have many friends. This annoyed me, so I decided to leap head-first into every sport there was. I was terrible. I came home night after night looking like an ad for the Blue Cross.” He was an excellent student, but purposely lowered his grades for a while in order to fit in as a “regular guy.” His gang in his neighborhood picked distance running as “that day’s form of athletic torture.” When he was still 13 in 1954. He jumped in head-first and started to run. He discovered that there were races of a mile and further. He also learned about the current local running hero and Olympian, Browning Ross (1924-1998).

Osler heard about a 30K race, a national championship, which was scheduled for Atlantic City. He went to watch it and met Ross for the first time. Ross won, and Osler got into the finishing picture by holding the finish-line tape.

Osler grew up in Camden, New Jersey. He had dreams he would be the first person to break the four-minute mile. He went to work training by running around his block. In 1954, England’s Roger Bannister was the first to break the four-minute mile barrier, which crushed Osler’s dream. His best mile was 4:54, which was disappointing to him, but he was one of the best high school milers in Camden. He finished his first marathon when he was 16 years old with a time of 3:27. In high school, he excelled in his classes, especially in the sciences. At Camden High, he was instrumental in getting a cross-country team established.

Early on, Osler was pretty much self-taught using things he found about running. read. He eventually found a seasoned running mentor, John “Jack” Albert Barry (1925-1993), from who competed against elite runners such as Browning Ross and Ted Corbitt.

For more details of Osler’s early running life, read an excellent article and Osler interviews conducted by Coach Jack Heath: The Running Chronicles of Tom Osler.

Off to College

Osler’s father was a plumbing contractor and sacrificed to make sure Tom went to college. In 1957, he went to Drexel Institute of Technology in Philadelphia, where he studied physics and won many academic awards. Osler loved running and found time during his busy college life to be deeply involved with road running as well.

Road Runners Club of America

In 1959, Browning Ross invited Tom Osler and others to witness the National Indoor Track Meet at Madison Square Garden. While there, representatives of various running districts got together at the Parmount Hotel and organized the Road Runners Club (RRC). Osler became the first co-secretary of the RRC. He raced multiple times a month in many shorter races put on by Ross in Philadelphia and throughout New Jersey.

Running Improved

For his first six years of serious running, he raced at every opportunity. In a field of about 50 runners, he would finish about 15th to 20th. But over-training started to plague him. He said, “I had a sciatic nerve condition that left me unable to walk. I still remember going out to train and going so slowly due to hip pain that even the dogs looked at me, puzzled. They couldn’t decide if I was running or not and were confused as to whether to chase me.” He soon figured out that rest and healing were just as important as training.

Stopped by the Police

Frequently he was stopped and questioned by police while running who thought he was running to try to get away after committing some crime. Once in 1964 while running, Police pulled over and pulled him into their police car, thinking he was a car thief they were looking for.

Becoming an Elite Runner

Osler became lifelong friends with future ultrarunning legend, Ed Dodd, in the early 1960’s, when Dodd was still in high school. They would do long training runs together. In 1965, at the age of 25, Osler was “beaten soundly” by Dodd, age 19, who became captain of St. Joseph University cross-country team. This increased Osler’s motivation and “the old competitive zeal was put into high gear.” When they would become tired during their runs, Tom sang a little ditty, “Going down the road feeling bad, feeling bad. I’m going down the road feeling bad.”

In July 1965, Osler went to Falls Church, Virginia, to compete in a one-hour track run against a highly competitive national field. He hoped to finish in the top ten. He ran away from the field, lapping them, and won with 11.3 miles. He became highly ranked in the nation for 1965 and won the 25 km national championship. He raced nearly every weekend and won about 30 races in 1965 for distances of three to fifteen miles, both on roads and cross-country.

In November 1965, Osler put on the first William Ruthruff marathon in Philadelphia in Fairmont Park. After a number of years this turned into what became The Philadelphia Marathon.

In 1966, Osler became a math instructor at St. Joseph’s University in Philadelphia and continued his prolific racing and winning. In 1967, he set his marathon personal best at Boston, finishing 16th with a time of 2:29:04. That year he also won the National 30 km Championship.

Ultrarunning

In 1967, Osler was inspired by Ted Corbitt to try ultramarathons. He explained, “1967 was my best year as a competitive runner. I had been racing the marathon and shorter distances for thirteen consecutive years. The National AAU fifty-miler was scheduled for Poughkeepsie, New York, on Thanksgiving Day. Having won the National AAU Thirty Kilometer Championship in the spring and placing fourth in the AAU Marathon, I decided to run the fifty-miler, even though I had never gone beyond thirty miles in training.”

With running buddies, Neil Weygandt and Ed Dodd, he began doing 50-mile training runs from Collingwood to Atlantic City, New Jersey. On August 13, 1967, Osler won a club 40-mile fun-run in Egg Harbor, New Jersey. Confident that he could do well, he began preparing to run in the 50-mile national championship to be held in November 1967. He worked up his runs to 55 miles. He ran every afternoon after classes covering 75 to 80 miles a week and averaged 7.5 minutes per mile.

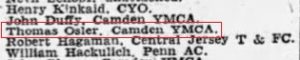

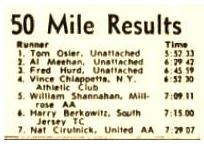

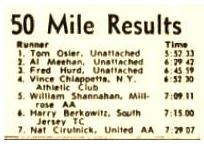

The first modern-era American 50-mile championship was part of the YMCA Thanksgiving Day Road Race, held in Poughkeepsie, New York. There were 13 starters, including legendary and future 100-mile world record holder John Tarrant, “the ghost runner,” who came from England to run. (see episode 63).

On race day, Osler, age 27, crewed by Dodd, took control of the 50-miler early and even led Tarrant. The last 40 miles were run in a steady downpour of freezing rain. Dodd recalled, “Tarrant had come alone to the race. Early on, Tom said check to on John and see what he needs and get it for him. So, I made several stops to get Tarrant his “biscuits and tea.” The moral is: Tom wanted to win fair and square.”

Osler won with 5:52:33, beating Tarrant by about ten minutes and said, “I’m very happy with my time. I had planned to do about 6:10 or better to win. I felt perfect for the first 41 miles, like I had just started. Then a slow weariness set in. It got worse as I went along and in the last lap was quite bad. It was cold but my main worry was that it might freeze.”

Dr. Osler

In 1970, Osler received a PhD from Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences of New York University. His dissertation was entitled, Leibniz Rule, the Chain Rule, and Taylor’s Theorem for Fractional Derivatives. He went on to teach at St. Joseph’s University and Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute and then worked in the mathematics department at Rowan University in New Jersey, in 1972.

Osler, the Author

Osler said, “At the time, the only monthly publication was the Long Distance Log, published by Browning Ross. It had about 200 subscribers, had been in existence for about 12 years and had lost money every year. I had a friend who was a runner and a printer. He told me that if I could get my book typed up, he’s print 2,00 copies for $200. He didn’t make any money on it and I didn’t expect to either, But Browning put a little ad in the Log saying that my book was available for one dollar. In a month, I sold 200 copies. I was afraid of losing my amateur status. As soon as I broke even, I took all my boxes of books, drove to Browning Ross’ house and left them on his porch. He wasn’t even home. I left a note that said, ‘They’re all yours, Browning. Use them for the Log.'”

Excerpts of the booklet were later published in Runners World in 1984. (Part One and Part Two.) The magazine stated, “Osler’s guide helped sweep American running into the 1970s, when Frank Shorter and other forces of inevitability took over. From today’s perspective, Conditioning is both amusing and amazing. It’s amusing because Osler foresaw the growth of distance running, but he could never have predicted that running would lose its simplicity. Conditioning is amazing for the number of times and ways in which it is simply right on the mark.” It indeed was trailblazing and is still referred to decades later. Amby Burfoot, who won the 1968 Boston Marathon, said he read the booklet and it and changed his training,

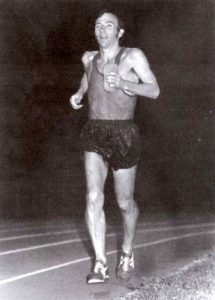

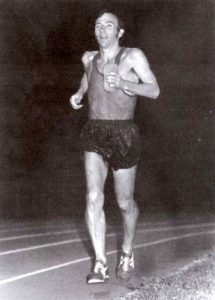

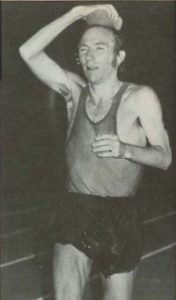

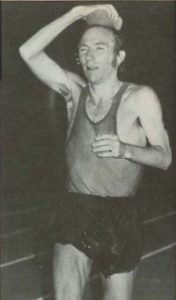

Glassboro 24-hour Run

![]()

![]()

He said, “Gradually, the light of dawn spread over the cinder track. I had thought before the run of the great beauty of watching the sun rise and set, and the night close in darkly while the run went ever on. I did my best to relax and stay fresh.” He reversed direction on the track about every half hour. During the day, the track thawed and became wet and mushy.

Osler reached 50 miles in 8:08:13 feeling good. The sun set at the 70-mile mark. The freezing ruts in the track became a problem. Many students arrived to run with him. He recalled, “At 80 miles, I began to grow weary. For the first time, I was no longer comfortable. I really wanted to stop and take a rest, but I thought it unwise.” He recovered at 95 miles and finished strong, reaching 100 miles in 18:19:27. The college president and reporters were there to offer congratulations.

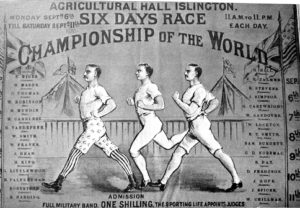

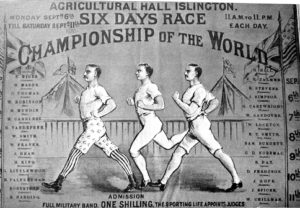

“He stopped for a rest and a warm spaghetti dinner and a ten-minute nap. After the break, he couldn’t get himself to run at all and proceeded to walk for the remaining time, covering 114 miles before he was done.” He ended up running 90 miles and walking 24 miles. He was delighted to discover that his post-race recovery produced no leg stiffness. He said, “I really don’t feel too bad.” Ted Corbitt told him that it was because of his frequent walks. Osler said, “I now knew how the great pedestrians of the past century had achieved seemingly impossible mileage.”

Ultra-Marathoning Book

During late 1977, Ed Dodd came in possession of an old, dusty scrapbook filled with news clippings about Pedestrian ultra events held in the Philadelphia from 1899 to 1903. This scrapbook, that would greatly impact the reestablishment of modern-era multiday ultras and 100-milers, was compiled by a Pedestrian from the Philadelphia area. In 1958, this aged dying man, had no heirs or friends to pass his carefully compiled treasure to. While a patient at Temple University Hospital, a kind medical school intern would sit and talk with this man about his professional running career at the turn of the century. The old man decided to give his treasure to this intern, Vernon Ordiway.

Vernon Ordiway (1934-) was from Bradford, Pennsylvania. He had received a degree from Princeton University, where he was a top runner on the cross-country team. Ordiway went on to attend Temple University Medical School, working as an intern in the hospital, and was an elite marathoner and graciously accepted the scrapbook gift. He then passed it on to Browning Ross who next gave it to Osler.

In 1977, Osler showed the scrapbook to Dodd. Fascinated by this history that included indoor races in smoke-filled arenas, Dodd decided to research the early sport deeper. He went to libraries, including the Library of Congress, and found more old newspaper articles on microfilm about the Pedestrian era. Dodd wrote, “We spent hour after hour discussing the incredible achievements of pedestrians. From these talks came a feel for and an understanding of what it was to be a pedestrian, and a desire to share this knowledge.” (Osler later gave the pedestrian scrapbook to Gary Corbitt (Ted’s son) to preserve.)

Dodd and Osler believed they had enough content to write a book, so Dodd went to work compiling the history of Pedestrianism for the first half of the book and Osler worked on the second half of the book, covering “The Art of the Ultramarathoner.” Regarding Osler’s section, he explained, “While I have been racing for 25 years, my interest in ultramarathons became intense only during the past five. For this reason, I am indebted to all the runners who trained and raced with me during this period. The marathon can be very fatiguing, but, when properly executed, ultras can be far less tiring than standard marathons. This apparent contradiction is resolved when the runner learns the art of mixing gently paced running with walking, the major new skill that the marathoner must acquire”

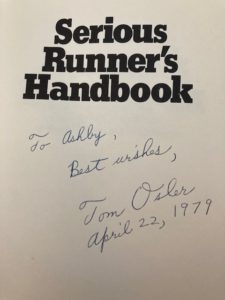

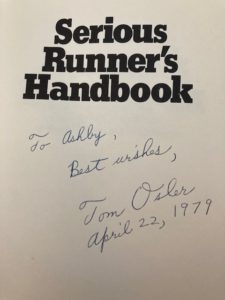

In 1979, Dodd and Osler published their book Ultra-Marathoning: The Next Challenge, a classic must-read book. Ultrarunning legend, David Horton, wrote, “That was the first book on the ultramarathon that I bought and read, the early Bible on ultrarunning.” Laurie Staton, among the first two to finish Wasatch Front 100 wrote, “This was the first ultrarunning book I read, and it still is right here on my bookshelf.”

The authors gave Davy Crockett permission to digitize and preserve this book on ultrarunnininghistory.com, making it available to download for free in pdf format, 58 meg.

In addition, with a PhD received in mathematics in 1970, Osler has published more than 150 papers on mathematics and physics. He explained, “My early work on fractional derivatives included 16 papers that are still being cited today. In the past 20 years, I have published many papers in mathematics and physics. Most of these are expository papers, and include topics of historical interest on Euler, the zeta function, number theory, partitions, geometry and other subjects.”

Later Life

In 2001, Osler was awarded South Jerseys Athletic Club’s Browning Ross Award. Ted Corbitt, the father of American Ultrarunning wrote at that time, “Tom Osler is a unique individual in terms of his nearly maximizing his potential talents as a long-distance runner, and in the area of his scholastic successes. In both cases, most of us never approach our potential, Tom Osler did. Tom Osler is also a nice down-to-earth human being with a good awareness of our society, a guy we are comfortable being around. There are those among us who watched in amazement as Tom Osler blossomed and emerged dramatically out of the pack to become an all-conquering champion runner.”

In 2003, Osler suffered a stroke but recovered. Two years later, he had another serious artery blockage that made him decide to retire from serious racing, but he did start walking and running again.

In 2020, Osler was 80 years old and still teaching math at Rowan University, with a teaching career of more than 54 years.

When asked why he ran, he replied, “Running offers both pleasure and pain. There is nothing like the purification of the soul through running. Running helps you connect with what is important in your soul.”

Tom Osler’s professional awards:

- The Gary Hunter Mentoring Award presented by the American Federation of Teachers, 2008

- The Editorial Excellence Award from the journal “Mathematics and Computer Education”, 2009

- The Mathematical Association of America, New Jersey Section, Distinguished Teacher of Mathematics Award, 2009.

- Oslerfest: (In honor of my 70th birthday) A two-day National Mathematical Conference at Rowan University, 2010.