Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 32:54 — 39.5MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

For both ultrarunners and hikers, the Grand Canyon is considered by most, one of the greatest destinations to experience. Thousands make their pilgrimages each year to experience the joy of journeying across the Canyon’s great expanse, rim-to-rim (R2R). Crossing the Canyon and returning back is an activity that has taken place for more than 125 years. Native Americans crossed the Canyon centuries earlier.

For both ultrarunners and hikers, the Grand Canyon is considered by most, one of the greatest destinations to experience. Thousands make their pilgrimages each year to experience the joy of journeying across the Canyon’s great expanse, rim-to-rim (R2R). Crossing the Canyon and returning back is an activity that has taken place for more than 125 years. Native Americans crossed the Canyon centuries earlier.

During the spring and fall, each day people cross the famous canyon and many of them, return the same day, experiencing what has been called for decades as a “double crossing,” and in more recent years, a “rim-to-rim-to-rim” (R2R2R). Anyone who descends into the Canyon should take some time learning about the history of the trails they use. This article tells the story of many of these early crossings and includes the creation of the trails, bridges, Phantom Ranch, and the water pipeline, the things you will see along your journey. Hopefully this will help you to have a deeper respect for the Canyon and those who helped make it available for us to enjoy.

| New Book! Grand Canyon Rim to Rim History. This book shares a 130-year history of the Canyon crossings and contains twice the amount of content and stories compared to these articles. Order on Amazon |

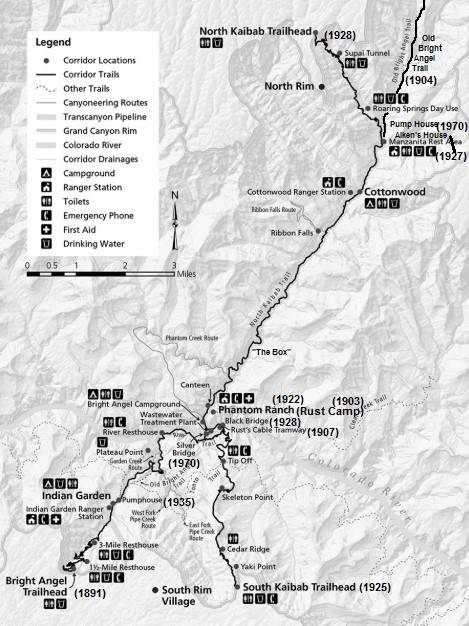

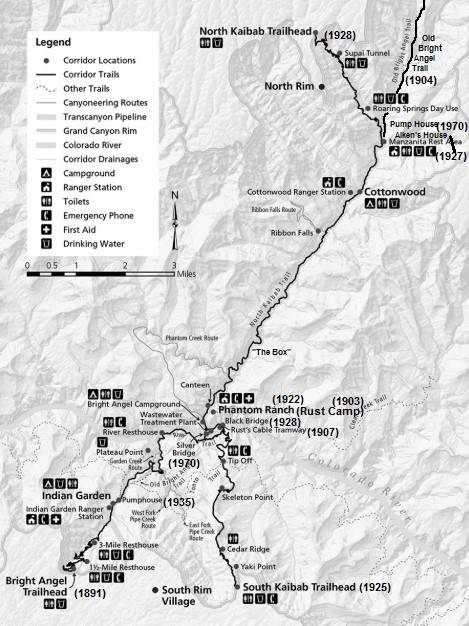

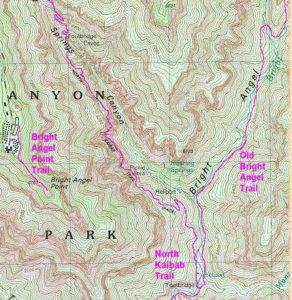

Introduction

Today if you hike or run across the Grand Canyon you have choices. You can start from the South Rim or from the North Rim. A South start is more common. On the South side, you can use either the Bright Angel Trail from Grand Canyon Village, or the South Kaibab Trail that starts a few miles to the east, using a shuttle to Yaki Point. On the North side, the North Kaibab Trail is used. These are the main trails into the Grand Canyon and referred to as the “Corridor Trails,” used by the masses and mule trains. Today, there are two bridges along the Corridor to cross the Colorado River, Black Bridge or Silver Bridge.

When this history story starts abut 1890, there was no Grand Canyon Village, no Phantom Ranch at the bottom, and these trails did not exist. There were few visitors to either Rim because they lacked roads and there were no automobiles yet. Early miners used many places to descend. This article will concentrate on the corridor region near Grand Canyon Village where most modern crossings are taking place.

Creation of Bright Angel Trail (South Side)

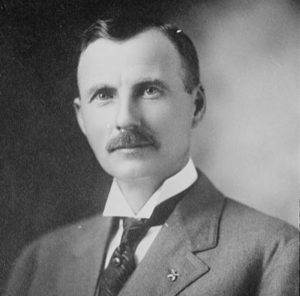

The upper part of Bright Angel Trail, coming down from the South Rim, was originally a route used by the Havasupai to access what became known as Indian Garden, halfway down the Canyon, about 3,000 feet below. In 1887, Ralph Cameron (1863-1953), future US senator of Arizona, prospected and believed he found copper and gold near Indian Garden. He said, “At that time my only purpose in building the trail was to use it in pursuing mining operations.”

Work began on December 24, 1890 and it would take 12 years to complete. In 1891 Peter D. Berry, (1856-1932), longtime friend of Cameron succeeded in obtaining rights for the trail, including rights to collect tolls which were not collected until 1901. Berry had also helped engineer the Grandview Trail (Berry Trail) further east. Other trails were being used. Hardy tourists were descending down to the Colorado River using the Bass Trail far to the west. By the end of 1891, after spending $500, and two months of labor, a very rough trail existed that descended the Bright Angel fault to Indian Garden.

The trail’s name

Originally called the “Cameron Trail”, by 1892 the trail was also named “Bright Angel Trail.” It would cost about $100,000 and 12 years to fully build, and at its height was worked on by 100 men. How did the trail get its name? This is a subject of entertaining legend and folklore. One story was told by “Captain” John Hance (1840-1919) who came to live at the Canyon about 1883. He was famous for his stories and yarns about the canyon. He said that a beautiful girl who the men thought looked like an angel came to stay at the Canyon and would descend often down the trail. One day she never came back up, was not seen again, and called the Bright Angel.

Another legend was told about a Catholic priest who explored the North Rim in the late 1800s and stopped at the top of what became known as Bright Angel Creek. He was out of food and water and laid down to die. A beautiful Indian woman came to his camp and provided him food and water. “For her kindness he gave her his blessing and termed her the bright angel whom God had sent to him.” The truth is that John Wesley Powell (1834-1902) named Bright Angel Creek as a contrast to another creek named “Dirty Devil.”

In 1906 the United States board of Geographic names changed the name of Bright Angel Trail back to Camerons Trail. However it was still referred to by Bright Angel Trail. Cameron had to remind people of its official name. Several years later it was changed back.

Bright Angel Trail construction

Efforts in the early 1890s only concentrated on the trail down to the mines at Indian Garden. It wasn’t until 1898-99 that work started below there to the river, for tourists. Thankfully there were no bad accidents during construction. One worker said, “Fifteen hundred feet of the trail known as the ‘Devil’s Corkscrew’ had to be blasted out and this is what I consider the best engineering feat of the work.”

Traces of the Original Devil’s Corkscrew can still be seen today if you head east on the Tonto Trail from Indian Garden and look down the next drainage where the old telephone poles descend. It starts on the west slope and then the east slope. This drainage used to be called Salt Creek. Early tourists had to dismount and walk their saddle animals down these harrowing set of switchbacks.

To build what is known as Jacob’s Ladder, a steep series of switch-backs, workmen had to swing down with ropes 100 feet to drill holes in the rock which blasting powder was inserted.

Workman James Murray escaped serious injury one day. A large boulder weighing about nine tons had fallen on the trail and needed to be removed. Holes were drilled and blasts put in for the charge to go off simultaneously. One only went off but Murray didn’t believe it. A fellow worker said, “He laughed at my fear and seated himself on the rock, proceeded to roll a cigarette. I called to him to jump, as I was satisfied but one blast had gone off, and for some reason he did so. He was not an instant too soon, for as he left the rock the powder exploded and pieces of the stone flew in all directions. Murray was knocked down and covered with rock, but fortunately he was not badly hurt.”

The greatest hardship of trail construction was getting provisions to the Canyon from 75 miles away. Teams of horses became snow-bound and the workers ran out of provisions. They had to use snowshoes to bring supplies in. From the rim it then had to be packed down to the workers. There was no water on the rim and it had to be hauled from 18 miles away. They had to sleep at times on the steep cliffs using a tarp as a blanket because there was no room for a tent and they would wake up in the morning covered with a foot of snow. The work was so hard and conditions so poor, that it was difficult to keep men employed.

The first known double crossing hike occurred in 1891. Dan Hogan (1871-1935) and Henry Ward went down the rough miner’s trail, crossed the river and bushwhacked their way up Bright Angel Canyon to the North Rim. They then returned by the same route. In 1892 evidence that the ancients lived along the trail could still be seen half way down. Cliff granaries existed with doors about 18 inches by 12 inches.

In 1896, Sanford Rowe who owned property on the rim was hard at work leading a “large force” of men improving the trail. It was believed the tourists started using the trail during 1896. A hotel was in the plans to be built at Indian Garden. One 1896 hiker said, “The climb out of the canyon is a trying ordeal at the best. On foot it is appalling, for a mile an hour is a fair average speed, and unknown muscles are soon stretched to the snapping point.”

Early Mining

The main motivation at that time to descend into the Grand Canyon was to prospect for precious metals. In 1899, William F. Hull led a company of prospectors down Bright Angel Trail. He said, “We packed our effects, including our boat, on a horse.” The boat was made out of canvas, about fourteen feet long. “On getting to the river, at the bottom of the steep inner gorge, we put it in shape and two of us embarked. With that frail, canvas-covered boat it took all our nerve and every faculty on a strain to keep afloat and avoid the constant whirlpools and mad counter-currents on every side. More than once we thought for an instant that our time had come.” On reaching the north side of the Canyon, they claimed to find a ledge with a vein of copper nearly 100 feet wide located about 1,000 feet above the river. Later that year, W. Frank Russell lost his life trying to cross the river in a canvas boat in an attempt to prospect the supposed vein. He couldn’t swim and he was last seen clinging to the capsized boat. His remains were found several years later buried in a sand bar several miles downriver.

Tourists arrive

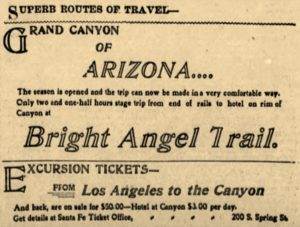

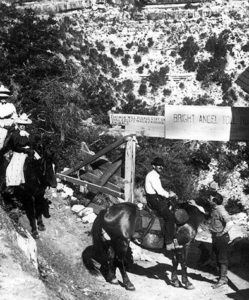

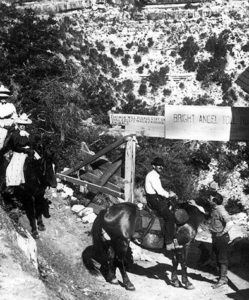

In 1900, the railroad was completed far enough to bring tourists from Williams, Arizona to the Grand Canyon by rail and stagecoach for $10. Tourists could descend into the canyon on mules or horses.

By 1902 the train had made its way all the way to the canyon where a small temporary hotel existed at the head of Bright Angel Trail that could accommodate 35 people. A much larger one was in planning stages (El Tovar) being constructed by the railroad.

One tourist of the time recorded, “We reached the canyon about 10 o’clock at night. The porters of the Bright Angel hotel met the train with lanterns and handcarts. I followed a flickering lantern up the hill to the hotel. I stepped into the hotel sitting room. The walls were covered with Indian blankets and skins of wild animals and decorated with deer horns and pictures of the canyon. I was told that owing to the crowded condition of the hotel I would have to sleep in a tent.” Horse and mule trains brought tourists down to Indian Garden and Plateau Point. “There, with the subdued roar of the water in our ears, we ate our lunches and climbed about the rocks and chased the nimble lizards.”

Toll Trail

By 1903 traveling down to the river and back in one day either by foot or by horse was possible. That year, Cameron convinced government authorities that he had legal claims to the trail. He bought out Peter Berry’s interests for trail about 1902. The Secretary of the Interior then granted Cameron exclusive rights to Bright Angel trail, enabling him to make it into a toll road.

Cameron built a two-story hotel with adjoining tent cabins at the trailhead and soon charged a toll of one dollar to use the trail, plus fees for drinking water and to use outhouses at Indian Garden, bringing in about $1,000 per month. Immediately legal challenges reached the courts from others to prove they constructed major portions of the trail, not Cameron. In May, 1903, District Court in Flagstaff ruled in favor of Lombard, Goode & Co’s. claim, but by the end of the year another case ruled in favor of Cameron. The railroad fought in the courts to try to prevent Cameron’s tolls, but in 1904 the Department of Interior confirmed Cameron’s rights to the trail. Arizona’s Coconino County eventually gained rights to the trail and received toll revenue.

Tourists Descend

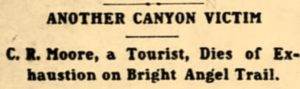

In July 1903, two Native Americans from Phoenix came to the canyon and set a speed record running down to the river in only one hour. “It was not so easy coming up.” As more tourists made their way into the inner canyon, deaths occurred. In August 1903, a tourist from Kansas who had hiked alone down to the river didn’t make it all the way back up. His body was found on the trail about a mile below the rim and his death was believed to be caused by heat exhaustion.

A 1905 description of traveling down the Bright Angel Trail to the Colorado River and back was provided by a lady who went by horseback to Indian Garden, and a little further, then by foot to the river and back. She wrote, “A strong person accustomed to walking can easily make the round trip on foot, but women rarely undertake it. A horse for the upward climb is almost a necessity. The trip from the mesa [rim] to the river is a trip of six or more hours. At “Jacob’s Ladder,” which is a flight of steps cut in the stone, we dismounted, leading the animals down. In three hours we made “Indian Gardens” a little camp is situated for the accommodation of the travelers consisting of a good-sized dining room and several tent houses, furnished with Navajo rugs and little white cots.”

“Resting a few moments, we started onward to the river. This portion of the trail is much steeper and difficult. In places one scrambles and slides down an almost perpendicular wall, the animals being abandoned at a zigzag place called the ‘Devil’s Corkscrew.’ The Colorado River was something of a disappointment to me as I hoped to see a specimen of the raging fierceness of its rapids or waterfalls. Here instead it is as turbid as a sea of frothy mud and uninteresting.”

The trail ended at that point, at the mouth of Pipe Creek. There was no River Trail yet cut into the cliffs. Returning to Indian Garden they had a “fine dinner furnished us by Japanese cooks and waiters,” and then went by horse back up to the rim.

Indian Garden Mining

For centuries Native Americans seasonally occupied Indian Garden for it spring and level land suitable for planting. There was also shelter in nearby caves. By 1903, Ralph Cameron came to an agreement with the Havasupais still living at the site that he could establish a camp for tourists and he files several mining claims. He first had seven tent cabins, provided meals and had a phone line to the south rim. It was called “Cameron’s Indian Garden Camp.” Within the next few years he planted cottonwood trees, dammed the creek to irrigate a garden, and constructed several buildings. Cameron’s caretaker tent existed near today’s junction with the west Tonto Trail. The Kolb Brother’s studio was nearby.

In 1912 Cameron sold 35 mining claims near Indian Garden and Devil’s Corkscrew for five million dollars to a investors in Pennsylvania. It was reported that the the investors “intend to place immense milling plants on the ground and construct an electrical plant” at Indian Garden. The deal fell through. In 1913 Cameron was mining platinum near Indian Garden and hoped to still lease mining rights to the Pennsylvania company, but not with a plan to build huge plants. As it turned out the ore was tested carefully and no platinum was found.

By 1917 Cameron was no longer maintaining Indian Garden. It was described as being filthy and disgraceful. By the early 1920s, Garden Creek was seriously polluted and trash littered the area. The National Park had not yet assumed control of the area and it would continue to be a travel dump for several more years.

Bright Angel Trail improvements

Bright Angel Trail on the North Side

In 1897 F.S. Burt and Sam Hubbard Jr. ventured across the river and explored up Bright Angel Canyon and discovered Roaring Springs. They reported “the discovery of a big waterfall, north of the river several miles. The water seems to pour out of a cave from a perpendicular side of a high wall of red rocks and judging from the distance it was thought it must be fully fifty feet wide.”

In 1900, John Fuller, a young herdsman, who lived seasonally on the North Rim, descended down Bright Angel Canyon at the request of a woman who had lost her husband trying to run the Colorado River in a boat. Fuller agreed to search for his remains. He had great difficulty descending and two horses fell over a cliff and died. He finally reached the future site of Phantom Ranch, near the River. There, he found a deserted camp and a lone Burro. Apparently another company, intending to return had also perished in the Colorado River. The tame burro, that became name Brighty, would go on to live wild in the Canyon for two decades, climbing up to the North Rim in the summer and going back down in the Fall.

In 1902, Edwin “Dee” Woolley, the Mormon leader in Kanab, Utah, started to pursue a vision to allow travel across the Grand Canyon. To descend into the canyon from the North Rim, he chose to try a route down from the head of Bright Angel Creek, about five miles northeast of the current North Kaibab trailhead. He and two others explored. There was no trail used by humans there. They found some game trails that helped them descend to the creek bottoms and concluded that a trail could be made.

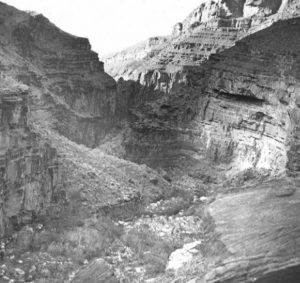

Later in 1902 a group of surveyors, led by Godfrey Sykes, descended the same route to consider building a facility to generate electricity. They cleared brush, logs, and boulders. Once down to the wider valley. they continued to follow the boulder-filled Bright Angel Creek to the Colorado River, crossing the creek 94 times along the way and mapped the route.

A serious proposal was brought forward in 1902 to dam Bright Angel Creek probably at “The Box,” to generate electricity to be taken to Flagstaff, Arizona. A company was formed, the “Grand Canyon Electric Power Company.” It was estimated that the plant would be up and running by 1903.

In 1903, separate survey of Bright Angel Canyon took place by the U.S. Geological Survey, led by François Émile Matthes (1874-1948). His team was surveying many sections of the canyon and its rims. In the fall of that year they reached the top of Bright Angel Canyon and were surprised to see two men, Sidney Ferrall and Jim Murray coming up with a burro. They had crossed the canyon rim-to-rim and planned to return. Two of the survey team went down ahead to cut brush and roll off logs and boulders for the survey pack train. The entire team began the descent on November 7, 1902. “So steep was it in certain places that the animals fairly slid down on their haunches.” By noon they made it down to the junction with Roaring Springs Canyon. They crossed Bright Angel Creek 94 times and made their camp for the night prior to entering “The Box.” It rained that night and the next day they looked back up to the North Rim and saw that snow had fallen. They spent several days in Bright Angel Canyon mapping it out and then went to the Colorado River where a prospector kindly let them use his boat to cross and head up to the South Rim.

As work progressed on the electrical proposal, a man was posted year-round at Bright Angel Creek to watch over the power company’s interests. In 1903 a company man came to relieve a watchman. They met up at Indian Garden on the south side of the Colorado River, and the first man went back down with his replacement to show him where the camp was. They attempted to cross the River at “Cameron’s ramp” at the mouth of Pipe Creek, but they were never seen again and the burros on the other side were still waiting for them. In 1904 Andy Cannon spent nearly a year at Bright Angel Creek as a watchman. For three months of that time he didn’t see a single person. Power plant plans were soon abandoned.

Woolley formed the “Grand Canyon Transportation Company” in 1903 and petitioned the county for a toll road on the North Rim and down into the Canyon. Work started in 1903 “hacking out some rock and vegetation. The rough trail zig-zagged down a steep ridge, two miles to the creek bottoms.” The entire trail soon was called also called “Bright Angel Trail,” the same name used for the trail on the south side of the Colorado River.

A 1903 visitor wrote, “Within a very few years it is to be hoped that the Bright Angel trail of the north side will be as well-known as the Bright Angel trail of the south side.” (Today the upper section of this trail is known as the “Old Bright Angel Trail.” It is an unmaintained trail, and still can be hiked down by skilled hikers from the North Rim to the bridge below the Manzanita Rest Area.) Woolley’s vision was to connect the south side’s Bright Angel trail to the north side’s Bright Angel Trail resulting in one Bright Angel Trail to be used to travel from rim to rim.

In 1904, William.W. Bass (1849-1933) petitioned to have a mail route established using the Bright Angel trails to deliver mail to Ryan, a mining town that existed near present-day Jacobs Lake.

In 1905 Woolley was granted a Forest Service permit for a North Rim road, but it couldn’t be a toll road. He also received rights to establish a camp located near the mouth of Bright Angel Creek that was located about a half mile closer to the River than present-day Phantom Ranch. Woolley’s hope was that it would become a tourist camp.

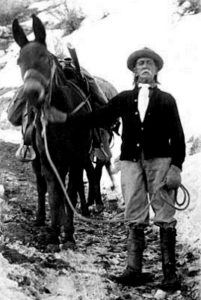

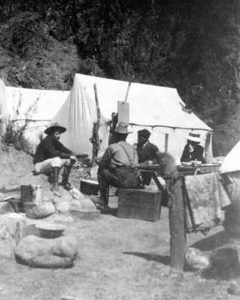

Woolley’s son-in-law, David D. Rust (1874-1963) joined the company in 1906 and went down into the Canyon to work as the manager and foreman with those who had been building the trail. Day after day they chipped out a graded trail with pickaxes on the steep side hills. By the end of the year there was a “suitable” trail in place from the North Rim to the Colorado River and the workers celebrated by taking a “plunge” in the River. The nearby camp became named, “Rust Camp.”

Rust and his crew improved “Rust Camp” with irrigation ditches and then planted cottonwood trees by transplanting branches cut from trees found up Phantom Creek.

Crossing the Colorado River

Some adventuresome people would cross the river in a crude canvas or wooden boat, visit Rust Camp, and then venture up Bright Angel Creek on the north side.

In 1905 a “cable ferry” started construction to float both humans and horses across the Colorado River, a length of 500 feet. James S. Emmett of Lee’s Ferry oversaw its planning. The hope was, that travelers to and from Utah could use this crossing and go up Bright Angel Canyon to the North Rim instead of all the miles to the ferry crossing at Lee’s Ferry up the River. A large cable was brought down from the North Rim and the ferry system was completed in October 1906, going across near the mouth of Bright Angel Creek. Hunters started making use of it to get to the North Rim. For whatever reason, the cable ferry did not operate very long, probably because of safety concerns.

Double crossings

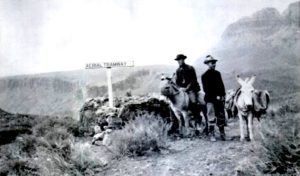

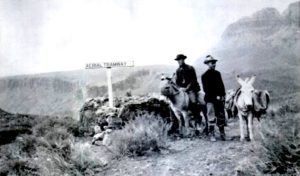

Cable tram across the Colorado

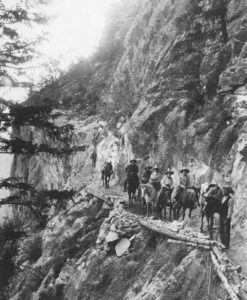

All the materials were brought on wagons to the North Rim from Utah, 200 miles from the end of the railroad. They then were brought down the very rough trail. “The long cable made heavy loads for several horses, a proportionate coil being backed on the first horse and the wire continued to the second horse which carried a similar portion of the wire, etc.”

A gasoline engine was installed in 1909 but would break down often. The cable tram was a key attraction in the canyon, but there was not always an operator stationed there. Most visitors weren’t daring enough to operate it themselves, so instead of visiting Rust Camp, they would return to the South Rim.

Linking the North and South Bright Angel Trails

To truly establish trans-canyon travel, what remained was to improve the trail on the south side from Indian Garden to the cable tram. To Travelers would cross the Tonto Platform to near Tipoff and descend a rough prospector trail called “Wash Henry Trail” to the tram. Cameron was in favor of a trail improvement plan but would not provide any money or resources to do the work, so it was up to Rust.

Rust knew that blasting a trail above the south Colorado River bank to Pipe Creek would involve difficult blasting, so in 1908 he turned his attention to improve “Wash Henry Trail” that went up the steep canyon above the tram to Tipoff. The new trail was called the “Cable Trail. (Present-day South Kaibab winds its way up to Tipoff and traces of the old Cable Trail can still be seen). The trail joined with a connector trail that crossed the Tonto Platform west to Indian Garden. The Cable Trail was completed in 1909.

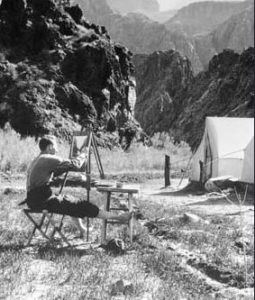

Rust Camp

By 1908, Rust Camp had six tourist tents, a cook tent, and herd of sheep. The following year, Rust ran into famous naturalists John Muir and John Burroughs coming down the South Bright Angel Trail and invited them to visit his camp. Rust wrote, “They were real people. We would sit down every hundred yards chatting and observing.” Rust stayed busy shuttling visitors from Rust Camp to the North Rim and back. It was the first year that the camp was open all season and hosted a few groups each week. Accommodations allowed prospectors, hunters, and a “few sturdy and adventurous

tourists” to camp comfortably in the Canyon.

One of the very early Grand Canyon runs took place in 1910. A rich woman was with a group on an outing on the north side of the canyon. An important telegram needed to be delivered to her. During the heat of July, a young man working at Kolb Brothers Photography volunteered to deliver it. The woman’s traveling group had a two-day head start on him, but he ran down into the 100-degree canyon, crossed the river in the cable tram, fording Bight Angel creek repeatedly, and reached the company somewhere up the canyon in only 6.5 hours.

Theodore Roosevelt’s rim to rim

In 1913, former President Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919) and his sons visited Rust camp, coming over in the cable tram, and was thrilled to be in the inner canyon. The crossing over the river took place during a terrible thunderstorm and all in the party were terribly drenched. Soon after, they reached Rust Camp was unoccupied. Rust was away at the time. Guided by two cattlemen, Roosevelt went on with a hunting party to the North Rim to hunt mountain lions for several weeks. Hundreds of the lions roamed the Rim at that time along with an estimated 15,000 mule deer. While already in the Canyon, there was some controversy whether Roosevelt had a proper hunting permit but Washington quickly granted a special permit “for scientific purposes” to let his party “bag as much game as desired.”

Because of the visit, and because Roosevelt had established Grand Canyon National Monument in 1908, Rust Camp was renamed to “Roosevelt Camp.” Despite the attention this visit caused, the camp still didn’t receive heavy tourist traffic. The trail was rough from the north, and the cable tram was pretty scary.

Tourists from the North Rim

In 1916 Woolley’s permit for Roosevelt Camp was revoked and Rust went to work at Zion Canyon to guide tourists. By 1917, the trail was not being maintained and the cable tram was abandoned. One traveler said that the Bright Angel trail going up the South Rim was a boulevard in comparison to the north side trail. He saw “the remains of the old cable cage rested on a ledge, where it had been left stranded, broken, and useless. Crossings were again accomplished with canvas boats into the 1920s.

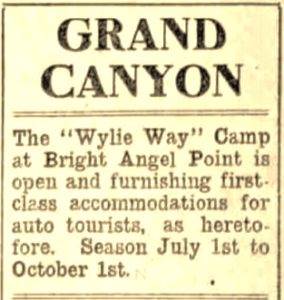

In 1919 the Grand Canyon National Park was established. That year a primitive camp was built on the North Rim near the present-day lodge. It was called the “Wylie Way Camp,” which attracted automobile tourists in their Model T Fords. Sleeping accommodations were wooden-floored cabins with a canvas roof. The camp ultimately served 120 daily guests.

The sanitary conditions at first were poor, but many people came to visit the Canyon. Brighty the burro was used haul water daily to the camp from a nearby spring 200 feet below the Rim. The camp later became known as “Bright Angel Camp.” More people from the Utah side started to visit Roosevelt Camp from the North Rim.

In 1921, “going up the Bright Angel Creek Canyon on the north side is exceedingly difficult. The mules ford the creek 86 times and several times are in the ice-cold water to their middles.” A mule trip across the Canyon typically took two days.

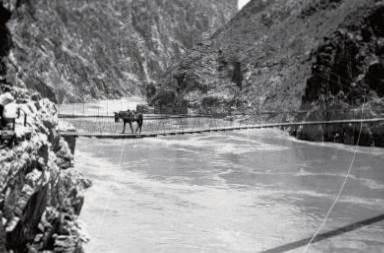

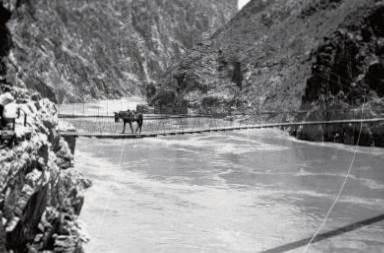

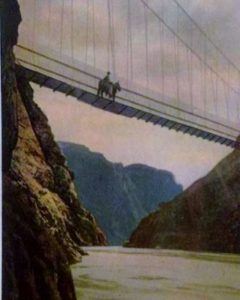

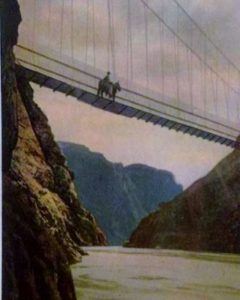

The Swinging Suspension Bridge

A news article reported, “This bridge will encourage tourist traffic to a natural wonder making the north side more accessible to tourists coming down from the south,”

A 1,200 pound cable needed to be brought down the Bright Angel Trail by mules. They first rehearsed the trip carrying down ropes of the proper length. The cable was successfully brought down on eight mules roped together. “The strange parade, with the gleaming, sinuous, snake-like freight, started on its way at the break of dawn and reached the bottom of the abyss after dark, having been on the trail over seventeen hours continuously. ”

Once the bridge was finally completed, The Park Service reported, “The bridge has linked the two sides of the Grand Canyon and makes possible trans-canyon travel.” (Crossing the Black Bridge to the south, you can still see the trail down to the right that went to this bridge crossing.)

Another guide gave an incredible story of the bridge. “He told us of taking 17 cattle over the suspension bridge and of having a big bull faint on starting over.The only thing that could be done was to lasso him and drag him across. Some burros refuse to go over the bridge and they are dragged across the beasts holding the floor boards of the bridge slashing into their sides unmercifully as they were dragged across.”

Early Single Crossings

Cut Canyon crossing hikes were now possible on foot the entire way. In 1921, Milo D. Gibson went from North to South in four days. It took him three days to reach Roosevelt Camp. Coming down the Bright Angel Trail from the North Rim was rough because it was “seldom traversed except by hardy hunters.” He described going down the trail, “In order to follow it, the creek has to be forded again and again, the depth ranging from knee-deep to waist-high. The drinking water was good at first and then became poor.”

Before 1921, the manager of the El Tovar Hotel on the South Rim explained why there were still few crossings. “The reason is that the trail up Bright Angel Creek is too difficult. It is too much to attempt except by a seasoned athlete who has no objection to strenuously roughing it. The almost ice-cold creek has to be crossed 117 times between the Colorado River and the North Rim in itself is no picnic.”

In 1921, Bonnie Gray, an very accomplished athlete and famous stunt rider from California, claimed that she had run across the canyon using the Bright Angel trails in 6:25. She said she “believes that this feat will never be equaled by a woman.” Given the rugged nature of the trail, and all the creek crossings needed at that time, the published time should not be believed.

About 1923, Robert Wylie McKee, about 12 years old, was living at the North Rim with his family that operated the camp. He wanted to hike rim-to-rim and felt confident that he could do it. He was in pretty good shape, and took a train to the South Rim. Without telling anyone, he went down Bright Angel Trail in the morning heading for the North Rim. He carried a box lunch, pocket knife, canteen, and an extra pair of socks. It was very hot and at Indian Gardens he suffering, probably from low electrolytes. He drank heavily, ate a sandwich, rested until the late afternoon and still felt rotten. He pushed on to Phantom Ranch, arriving at dusk. Since he didn’t have money to stay the night, he sheepishly called his mother using a new telephone line. She was relived because he should have returned home two days earlier. McKee stayed at the bottom for two days and recovered from his trek down. There were only two others at the bottom. They prepared him a lunch and he continued his journey in the morning. Because of all the creek crossings, by the time he reached Ribbon Falls, he had terrible blisters from wet feet and stopped his journey at the future site of Cottonwood Campground. He broke open a telephone box, called the North Rim again, and the next day they came down and hauled him up on a mule. It took about two weeks until he could walk normally again.

Phantom Ranch

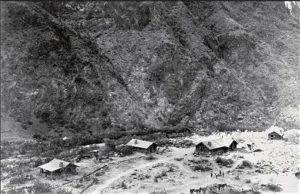

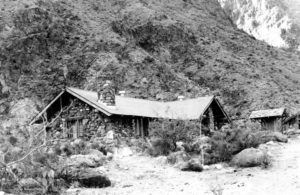

Roosevelt Camp was renamed to Phantom Ranch by Mary Jane Colter (1869-1958). Major construction of the Ranch began, initiated by the Fred Harvey Company in 1921 under Colter’s direction. It opened the next year with four cabins, a lodge with a kitchen and dining hall.

The Park announced that “the government will put the trail up Bright Angel Canyon into shape for easy traveling by women and children. Halfway up Bright Angel Creek toward the north rim, another camp will be built to be named Ribbon Falls camp.” In 1921-22, National Park Service trail crews started to greatly improve the trail north from Phantom Ranch, starting from the bottom up. They concentrated on the trail through “The Box.” a site of frequent floods, and eliminated about 40 of the 90+ Bright Angel Creek crossings by raising the trail above the creek bed.

More improvements wanted to be made but in 1922, Senator Ralph Cameron, who had fought for his control of the Bright Angel Trail for years, and his mining claims to the federal government, was now an enemy of the Park. He carried out a personal bitter war against the Park. In 1922, he fought hard and succeeded to deny $90,000 of funds for Park improvements. He said the expenditure of the funds would be “useless and worse than useless to gratify the whims of a few who would profit by the expenditures.” Cameron who in past years had lined his pockets with tens of thousands of dollars exploiting the Canyon, vowed to fight fund approval for all national parks. “I intend to do all I can to stop such fooled expenditures. It is no wonder that the people wonder why their taxes are large when so much money goes into such sink holes.” Months later the Senate authorized $75,000 for the Grand Canyon National Park. Cameron tried unsuccessfully to buy Bright Angel Trail from the county, eventually lost reelection, and left the area.

A guest in 1924 wrote, “At Phantom ranch, we found three sleeping cabins with four beds each, a larger central building with the kitchen and dining room, a garden that was just getting started, a barn and a chicken house. Green grass is all about and many small trees that have just been set out. Small boulders have been piled in rows making most of the fences. Two years ago, it was just desert.”

By 1925 four tents were added which could accommodate four people each and a wooden bathhouse with dressing rooms. In 1926 an electricity plant was added. In 1927 a large recreation building was built and in 1928 five more two-bed cabins were added along with today’s Canteen dining room. A 1922 dinner bell still hangs east of the dining hall. Raw sewage was piped to dump in the Colorado River before replaced with septic tanks and then a sewage treatment plant.

Royalty descended into the Canyon in 1926, Prince Gustaf Adolf (1906-1947) of Sweden, heir of the throne. His group of 18 went all the way to Phantom Ranch on a July day when it was 110 degrees at the bottom. The Prince, age 20, immediately went off alone to swim in Bright Angel Creek. (The prince was killed in a plane crash in 1947).

South Kaibab Trail

Cameron had influenced Coconio Country voters to defeat a measure that would have sold Bright Angel Trail to the federal government. County ownership of the trail made it difficult to manage the inner canyon. Without control of the trail and the continued tolls, the National Park Service moved ahead with plans to construct a new trail for tourists to use for free.

In 1922 the park service widened and improved the Cable Trail coming down to the Swinging Suspension Bridge from “Tipoff.” During the construction work on the trail, Foreman Rees Griffith (1872-1922) was descending a rope after some rock had been blasted away. Loose rock from above fell on him and killed him. He left behind a wife and five children in Fredonia, AZ. He was buried near the trail along the north side of the River. His burial-place and monument can still be seen from the trail.

Construction of the Kaibab trail used modern construction equipment that was being used to make automobile roads at that time such was compressors and jackhammers. Stray drill bits may still be found, along with traces of old drill holes in the rock faces. The trail route was chosen to get sun nearly year round, minimizing snow. The average grade was 18 percent.

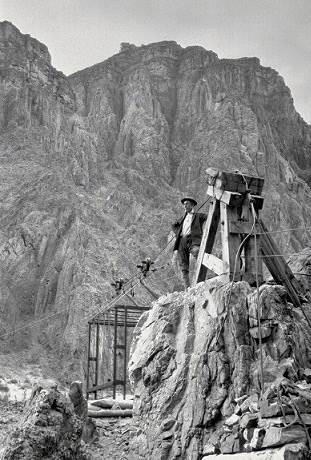

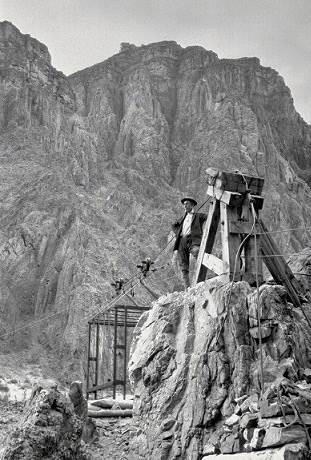

North Kaibab Trail

In 1924 work started on the North Kaibab Trail that would bypass the rough “Old Bright Angel Trail” and head up Roaring Springs Canyon to the North Rim. When it was proposed, engineers said “it can’t be done” but the trail work was started. Work was mainly performed on the trail during the winter because of extreme heat. Work required much blasting and hammering, including creating the 20-foot-long Supai Tunnel. In 1927 a cable conveyor system was put in from the North Rim to Roaring Springs to more quickly bring down equipment for trail building. “The trail was literally hewn from solid rock in half-tunnel section using high explosives, portable drills, and jackhammers.”

The North Kaibab trail was exposed to yearly spring runoff and landslides. For several years the park service employed a full-time trail worker to oversee trail maintenance. Even today, many seasonal workers maintain the trail each spring in April.

With all the visitors coming to the North Rim, the few springs near the top did not provide enough water. By 1928 a power plant was built below Roaring Springs to generate power for a pumping station to lift water 3,870 feet to the rim through 12,700 feet of three-inch steel pipe which can still be seen today. The heavy machinery to construct the plant and pump station was lowered on the special tramway.

Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim Series

- 46: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 1 (1890-1928)

- 47: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 2 (1928-1964)

- 48: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 3 (1964-1972)

- 49: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 4: Aiken Family

- 50: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 5: The Races

- 135: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 6: Early Guides

- 136: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 7: Prof Cureton

- 137: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 8: Kolb Brothers

- 138: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 9: Phantom Ranch

Sources

- Frederick H. Swanson, Dave Rust: a life in the canyons, 2007

- 1902 – Breaking a Trail Through Bright Angel Canyon

- 1925 – Building the Kaibab Trail

- 1928 – A Bridge Worthy

- Bright Angel Trail

- The Record (National City, California), Jun 30, 1892

- Omaha Daily Bee (Nebraska), Feb 23, 1896

- Weekly Journal-Miner (Prescott, Arizona), May 19, 1897

- The Birmingham News (Alabama), Apr 17, 1902

- Los Angeles Times, Mar 12, 1898, May 17, 1903

- Chicago Tribune (Illinois), Apr 1, 1900

- The Salt Lake Tribune (Utah), Jul 20, 1902, Jul 22, 1913, Feb 24, 1922, Sep 16, 1928

- Albuquerque Weekly Citizen (Arizona), Jan 24, 1903

- The Coconino Sun (Flagstaff, AZ), Aug 30, 1902, Jun 23, 1906, Jan 9, Aug 27, 1904, Nov 4, 1905, Aug 16, 1912, Jan 28, Apr 22, Aug 5, Oct 7, 1921, Feb 17, 1922

- Deseret Evening News (Salt Lake City, UT), Aug 29, 1903.

- Arizona Republic, Dec 13, 1896, Feb 25, 1899, July 16, 1899, Aug 11, 18, 1903, Nov 10, 1905, Aug 1, 1911, May 27, 1928, Oct 21,28, 1974, Dec 15, 2007

- Albuquerque Journal, Dec 29, 1902, Oct 28, 1905

- El Paso Herald (Texas), Dec 29, 1903, Dec 29, 1921

- The Topeka Daily Herald, Dec 22, 1906

- The Cooper Era and Morenci Leader, Jul 8, 1910

- Salt Lake Telegram (Utah), Jul 16, 1913

- Panguitch Progress (Utah), Nov 19, 1915

- 1920 Rules and Regulations

- New York Herald, May 1, 1921

- The Standard Union (Brooklyn, New York), Jun 26, 1921

- The Chantute Daily Tribune (Kansas), Sep 21, 1921

- Essex County Herald (Vermont), June 16, 1921

- Pottsville Republican (Pennsylvania), Oct 19, 1921

- National Geographic Magazine, June 1921

- Williams News (Arizona), Feb 21, Jul 25, 1903, Jun 25, 1904, Oct 28, 1905, Feb 17, 1922

- Iowa City Press-Citizen (Iowa), May 14, 1924

- The San Francisco Examiner, Feb 8, 1925

- The San Bernardino County Sun, Mar 4, 1928

- General Information Regarding Grand Canyon National Park, National Park Service, 1933

- Mike Campbell, “The Bright Angel Trail: Then and Now”, 2014

- Michael P. Ghiglieri and Thomas M. Myers, Over the Edge: Death in the Grand Canyon

- Grand Canyon History Facebook Group

- National Register of Historic Places application for Bright Angel Trail

- Martha McKee Krueger, Bobby, Brighty, and the Wylie Way

- Dick Brown, Pioneer Trails “to” Grand Canyon