Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 31:21 — 39.1MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

This is the second part of the Rim-to Rim story. Read/Listen/Watch to Part 1 here.

This is the second part of the Rim-to Rim story. Read/Listen/Watch to Part 1 here.

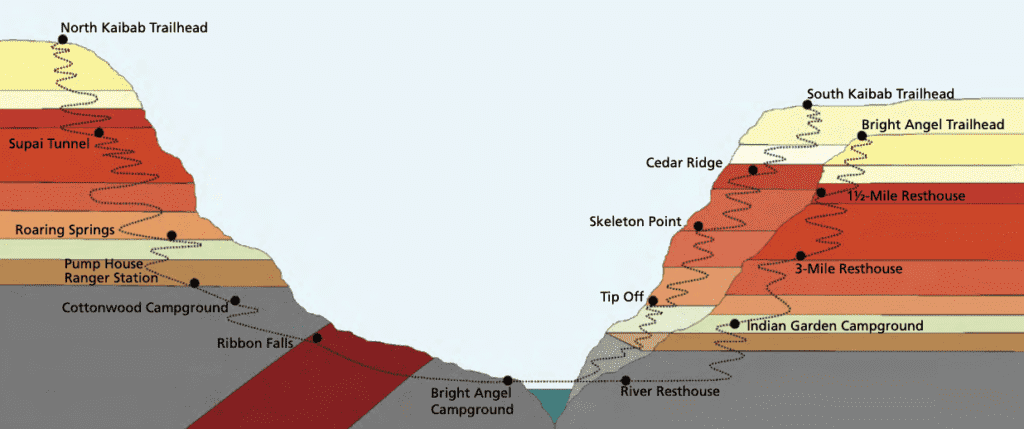

Descending into the inner Grand Canyon is an experience you will never forget. Part one covered the very early history of crossing the Canyon from 1890-1928. Trails that could accommodate tourists were built, including Bight Angel and South Kaibab trails coming down the South Rim. A tourist in 1928 explained, “the Kaibab trail is a fine piece of work, easy grade, wide and smooth, while the Bright Angel trail still belongs to the local county and is maintained by it, and is steep, narrow and poorly kept up. Each person going down Bright Angel pays a toll of one dollar.” There was no River Trail yet, so those who came down the Bright Angel Trail used the Tonto Trail at Indian Garden to connect to the South Kaibab Trail. “The Tonto trail was perfectly safe and the scenic views were wonderful.”

Phantom Ranch was established in the early 1900s. The same tourist continued, “It is beautiful down here now in the dusk with the towering cliffs above and a mountain brook singing along in front of my cabin, and the weather at least 20 degrees warmer than up on the rim, where the ground is covered with snow. After a hearty, well-cooked beefsteak dinner, I am settled in a one-room, stone walled, cement floored cabin, with a roaring fire in a cute corner open fireplace.”

Phantom Ranch was established in the early 1900s. The same tourist continued, “It is beautiful down here now in the dusk with the towering cliffs above and a mountain brook singing along in front of my cabin, and the weather at least 20 degrees warmer than up on the rim, where the ground is covered with snow. After a hearty, well-cooked beefsteak dinner, I am settled in a one-room, stone walled, cement floored cabin, with a roaring fire in a cute corner open fireplace.”

The North Kaibab trail coming down from the North Rim was completed in 1928. The steep, rough Old Bright Angel Trail coming down the North Rim was abandoned and today is an unmaintained rugged route. A scary swinging suspension bridge spanned the Colorado River, bringing tourists over to Phantom Ranch. Multi-day rim-to-rim hikes had begun both from the North Rim and the South Rim. How all this came to be by 1928 is told in Part One. If you have not read, listened to, or watched Part One first, you should.

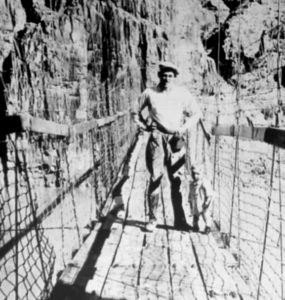

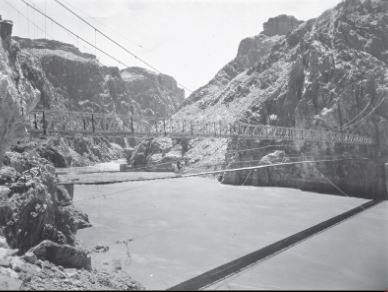

Black Bridge

In 1926. nearly 23,000 automobiles entered the park, bringing 140,000 visitors. As tourist traffic continued to increase to Phantom Ranch, a new bridge was needed. The swinging suspension bridge that was constructed in 1921 was nearly impossible to cross when it was windy. High winds had capsized it more than once. “In using the old swinging bridge, it was necessary for tourist parties to dismount in crossing, the animals being taken over one at a time. This caused congestion and delay at one of the hottest points on the trans-canyon trip.” One visitor mentioned, “We crossed the Colorado river on a frail looking bridge, one mule at a time only, rider unmounted, and the bridge waving up and down under the weight. Having gained so much weight since leaving home, I was obliged to cross considerably in advance of my mule.”

In 1927, $48,000 was quickly appropriated for a new bridge to connect the two Kaibab trails. Construction began on a new bridge on March 9, 1928 with nine laborers who established their camp on the confluence with Bright Angel Creek. The crew soon grew to twenty. All the 122 tons of structural materials were brought down into the canyon on mules except for the massive four main support cables. Forty-two men, mostly Havasupai Indian workers, spaced 15 feet apart, carried the huge 550-foot main bridge support cables down the South Kaibab Trail on their shoulders, about fifty pounds per man. Each of the four cables weighed 2,154 pounds.

“When they got to the bottom of the canyon, after getting rid of the cable, they went down onto a flat, gathered brush, made sort of a trench of it, and placed big boulders on the brush. Then they set fire to it. After the fire died down, they spread their blankets over a wooden frame that they had constructed, doused the rocks and live coals with water, and walked through this tunnel of blankets getting steam baths and then jumped into the muddy Colorado River.”

The location for the bridge was chosen to be about sixteen feet directly over the older swinging suspension bridge. There was no significant interruption of the traffic going over the old bridge as the new bring was being constructed. You can still see the path going around the cliff to where the old bridge was accessed on the south side. A tunnel on that side was excavated running 105 feet, allowing for a wider, direct approach to the new bridge.

On August 3, 1928 the new Kaibab Suspension Bridge” was complete. It would become nicknamed “Black Bridge.” It was rigid, wider (five feet), and stabilized by two wind cables. The bridge was purposely still narrow to prevent mules from trying to turn around. The bed was at first concrete on steel but it eventually was worn out and replaced by wood. Structurally, the bridge has been essentially unmodified since its original construction. Today it receives about 100,000 crossings each year and in 2019 was named a national historic civil engineering landmark.

On August 3, 1928 the new Kaibab Suspension Bridge” was complete. It would become nicknamed “Black Bridge.” It was rigid, wider (five feet), and stabilized by two wind cables. The bridge was purposely still narrow to prevent mules from trying to turn around. The bed was at first concrete on steel but it eventually was worn out and replaced by wood. Structurally, the bridge has been essentially unmodified since its original construction. Today it receives about 100,000 crossings each year and in 2019 was named a national historic civil engineering landmark.

Bright Angel Trail improvements

In 1928, with Ralph Cameron no longer interfering, the county finally sold ownership of Bright Angel Trail to the federal government. The Bright Angel Trail on the south side received an important face lift in 1932. The old Devil’s corkscrew area had been a constant problem from rockfall and wash-outs. Below Indian Garden, the trail was moved to follow Garden Creek and then to a totally new Devil’s corkscrew. The Park Service reported, “Many of the sharp zigzags have been eliminated, grades have been greatly reduced, and a heavy rock guard wall has been placed along the outer edge of the trail. Even the most timid now should feel no hesitancy in taking this scenic trip.” In 1933, more than 12,000 people used the trail.

About 1929, “a railroad man, familiar with the trails, walked from rim to rim in five or six hours. However, he took the cutoffs, and ran and slid much of the way down.”

Non-humans at Phantom Ranch

In 1929 a deer caused quite a stir crossing the Colorado River. The tame deer had a free reign of the corridor trail area. One day it was at Phantom Ranch with her two fawns. She jumped in the river, was taken by the current, and went over to the shore at Pipe Creek. Her fawns didn’t follow but went upriver and crossed at the tamer waters near Black Bridge. The fawns went up South Kaibab Trail to the Tonto Platform. The mother went up Pipe Canyon. Somehow they met up at Indian Garden.

In 1929 a deer caused quite a stir crossing the Colorado River. The tame deer had a free reign of the corridor trail area. One day it was at Phantom Ranch with her two fawns. She jumped in the river, was taken by the current, and went over to the shore at Pipe Creek. Her fawns didn’t follow but went upriver and crossed at the tamer waters near Black Bridge. The fawns went up South Kaibab Trail to the Tonto Platform. The mother went up Pipe Canyon. Somehow they met up at Indian Garden.

Also that year a colony of beavers cared for by the Park in upper Bright Angel Canyon migrated down to Phantom Ranch and started to cut down many of the beautiful shade trees that had been planted there.

The park rangers were at first patient with the small residents. “Park authorities have felt that the value of the few cottonwoods they destroy in this locality is far less than the value of the beavers themselves and the evidence of their activities as a tourist attraction. There are few places along main traveled trails where the tourist can see nearby old and new beaver cuttings.” They eventually sent the beavers back up the creek, but they kept returning for many years.

The park rangers were at first patient with the small residents. “Park authorities have felt that the value of the few cottonwoods they destroy in this locality is far less than the value of the beavers themselves and the evidence of their activities as a tourist attraction. There are few places along main traveled trails where the tourist can see nearby old and new beaver cuttings.” They eventually sent the beavers back up the creek, but they kept returning for many years.

In 1930, 100,000 fish eggs visited the ranch, brought from Montana. Rangers took the eggs on their backs from the ranch and planted them in side streams (Phantom Creek, Wall Creek, and Ribbon Creek). Fishing trout at Bright Angel Creek soon became a major reason for people to descend into the canyon. The first eggs had been brought down in 1920.

In 1930, 100,000 fish eggs visited the ranch, brought from Montana. Rangers took the eggs on their backs from the ranch and planted them in side streams (Phantom Creek, Wall Creek, and Ribbon Creek). Fishing trout at Bright Angel Creek soon became a major reason for people to descend into the canyon. The first eggs had been brought down in 1920.

A horse named “Old Bob” pulled a four-horse coach for more than a decade on the South Rim. He pulled kings and presidents. In 1922, as faster automobiles replaced his coach, Old Bob lost his job. Instead of being auctioned off, an official at the transportation company let “Old Bob” retire to Phantom Ranch to graze along Bright Angel Creek. In 1936 after nine years he was still an attraction at Phantom Ranch and was 31 years old.

Phantom Ranch

In 1922, a small cable tramway was constructed upriver from Black Bridge that was used to monitor the river’s water flow. It can still be seen today. Tourists from Phantom Ranch were at times given thrilling rides in the tram across the river and back, even at night in moonlight.

In 1922, a small cable tramway was constructed upriver from Black Bridge that was used to monitor the river’s water flow. It can still be seen today. Tourists from Phantom Ranch were at times given thrilling rides in the tram across the river and back, even at night in moonlight.

In 1930, Phantom Ranch was visited by about 500-600 people from June to September. The rest of the year had far less visitors because the North Rim was closed in early October. “They have accommodations of a central dining room, of a large recreation hall, designed for dancing, card playing and other amusements.” There was also a diesel-powered electric plant, a small orchard of peach trees, fig trees, and alfalfa tract. The cottonwood trees that were planted had grown to more than 50 feet high. A central restroom with shower baths was completed along with a sewer system. Prior to that raw sewage was dumped into the Colorado River.

In 1930, Phantom Ranch was visited by about 500-600 people from June to September. The rest of the year had far less visitors because the North Rim was closed in early October. “They have accommodations of a central dining room, of a large recreation hall, designed for dancing, card playing and other amusements.” There was also a diesel-powered electric plant, a small orchard of peach trees, fig trees, and alfalfa tract. The cottonwood trees that were planted had grown to more than 50 feet high. A central restroom with shower baths was completed along with a sewer system. Prior to that raw sewage was dumped into the Colorado River.

During peak times, about five employees stayed down there to take care of the visitors. “For some people the trip down the narrow trails is one of keen delight, while for others it is full of terrors which they have no desire to repeat.” A visitor mentioned, “I would have slept well had it not been for the croaking of the frogs: ‘You have to go ba-a-ack.'”

In 1932 it was observed, “Nearly every day we see long trains of pack mules going down through one rim to the other. The rim-to-rim tourist trips are apparently few.” For those who did venture up to the North Rim, they found the prices to be outrageous. A pound of butter was 40 cents and a quart of milk 19 cents.

Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) improvements

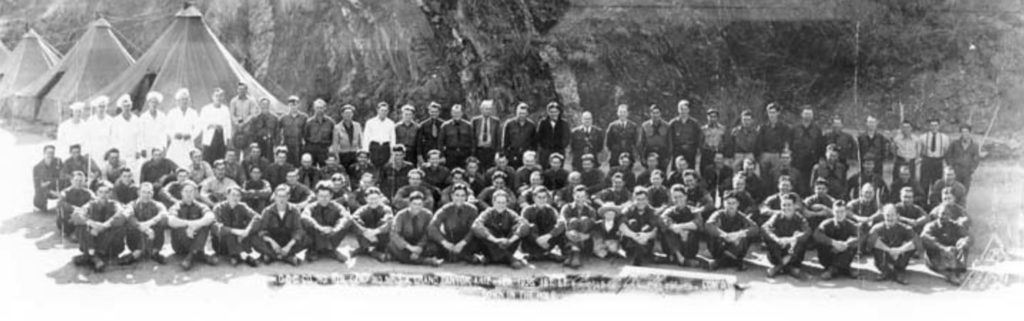

From 1933-36, Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) were assigned to improve Phantom Ranch. During the Great Depression, the CCC was a voluntary public work relief program that operated starting in 1933 for unemployed, unmarried men, ages 18-25. Each enrollee was required to serve a minimum six-month period, with the option to serve as many as four periods, or up to two years. They worked 40 hours per week over five days. In return they received $30 per month

From 1933-36, Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) were assigned to improve Phantom Ranch. During the Great Depression, the CCC was a voluntary public work relief program that operated starting in 1933 for unemployed, unmarried men, ages 18-25. Each enrollee was required to serve a minimum six-month period, with the option to serve as many as four periods, or up to two years. They worked 40 hours per week over five days. In return they received $30 per month

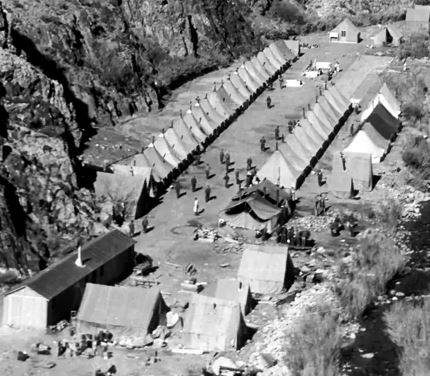

CCC company 818 arrived in October 1933 and established a camp in less than two weeks that was located at present-day Bright Angel Campground. “Company 818 is housed in six-man pyramidal tents, with a shack for showers, a newly completed mess and recreation hall, and a few odd tents for this and that and the other.” They would work for three years during the winters at the bottom of the Canyon. During the extreme summer heat of the inner canyon, the camp was moved up to the North Rim each summer, in the cool forest where they worked on other projects. These young men made the great impact completing dozens of projects, developing the corridor trail region so it could be enjoyed by many generations.

The average number of workers there was 200. It was known as the most difficult camp to supply among all the CCC camps across the country. The medical department did not approve of such an isolated camp because it would require 15 hours and 20 men to move a patient to a hospital. It was established anyway.

The average number of workers there was 200. It was known as the most difficult camp to supply among all the CCC camps across the country. The medical department did not approve of such an isolated camp because it would require 15 hours and 20 men to move a patient to a hospital. It was established anyway.

“The bugle sounded reveille at 6 a.m. to initiate the day’s activity. The top sergeant came to the tent doors and blew a blast on a whistle to make sure everyone was up and ready for breakfast at 6:30 a.m. The call to work came at 7:15 a.m. All enrollees were at the work center ready to report to their job supervisor for the day. The day’s work ended at 4 p.m.

The bugle sounded assembly at 5 p.m. for retreat ceremony, lowering of the flag, inspection, and the enrollees were at liberty to enjoy the evening participating in educational endeavors, writing letters, attending class, reading, or engaging in their favorite recreational activity. At 10 p.m. the bugle sounded ‘taps’ and the lights went out. Quietness swept over the camp.” A camp newspaper was established, appropriately named, The Ace in the Hole. It helped keep morale high, inform the boys, and gave them things to laugh at.

A massive amount of supplies except for water had to be transported to the CCC camp by a United States Army mule pack train, down the seven-mile South Kaibab Trail. Fifty pack and ten saddle mules made the trip daily. They would carry nearly 6,000 pounds, including 200 pounds of coal on the mules. The mules would also carry food, mail, and other supplies. “Day after day, strings of sinewy mules are herded down trail and up.”

A massive amount of supplies except for water had to be transported to the CCC camp by a United States Army mule pack train, down the seven-mile South Kaibab Trail. Fifty pack and ten saddle mules made the trip daily. They would carry nearly 6,000 pounds, including 200 pounds of coal on the mules. The mules would also carry food, mail, and other supplies. “Day after day, strings of sinewy mules are herded down trail and up.”

At times the top of the trail would be covered by five-foot drifts that would require a team of men to clear the trail for the mules. The camp always had 15 days of emergency rations. Once a slide closed the trail so supplies were brought down the Bright Angel trail, across he Tonto plateau, and then down to the camp using the lower Kaibab trail.

At times the top of the trail would be covered by five-foot drifts that would require a team of men to clear the trail for the mules. The camp always had 15 days of emergency rations. Once a slide closed the trail so supplies were brought down the Bright Angel trail, across he Tonto plateau, and then down to the camp using the lower Kaibab trail.

Wood detail

The CCC made many improvements near Phantom Ranch including the construction of a mule corral, two residences, two bridges over Bright Angel Creek. A large amount of wood was needed for the wood stoves as the CCC camp. The solution was to construct a tram near present-day Silver Bridge to transport driftwood over from the south side of the Colorado River.

The CCC made many improvements near Phantom Ranch including the construction of a mule corral, two residences, two bridges over Bright Angel Creek. A large amount of wood was needed for the wood stoves as the CCC camp. The solution was to construct a tram near present-day Silver Bridge to transport driftwood over from the south side of the Colorado River.

Those on wood detail were assigned to gather the wood from the sandbar, carry it to the tram, and load it on the cage. The tram operator would transport the wood across the river powered by a one-cylinder motor. The rest of the wood detail would unload the tram cage and haul to wood on a two-wheel cart to the camp pulled by a horse. Eventually, they just couldn’t get enough wood and sparks out of stove pipes kept burning holes into the roofs of all the tents, so coal was brought down to be used instead.

The River Trail

The CCC’s most difficult project was to construct the “River Trail.” It took them two and a half winters. This trail made trips much shorter and easier using the Bright Angel Trail to get to Phantom Ranch. It was carved out of the rock on the south side of the Colorado River and was said to be the “most hazardous of any of the trails that had been built by the CCC in the park.” It was first named “The Colorado River Trail” as a temporary name. The plan was to name it after the first man who died constructing it. But since there never was a fatality, the name remained.

The CCC’s most difficult project was to construct the “River Trail.” It took them two and a half winters. This trail made trips much shorter and easier using the Bright Angel Trail to get to Phantom Ranch. It was carved out of the rock on the south side of the Colorado River and was said to be the “most hazardous of any of the trails that had been built by the CCC in the park.” It was first named “The Colorado River Trail” as a temporary name. The plan was to name it after the first man who died constructing it. But since there never was a fatality, the name remained.

The trail was carved out of the cliff the entire length of the trail above the river from 40 to 500 feet. in one section the wind would always blow sand up from the beach below and thus the trail needed to go along the foot of the cliff at the top of the slow. Even today, that is a very sandy section.

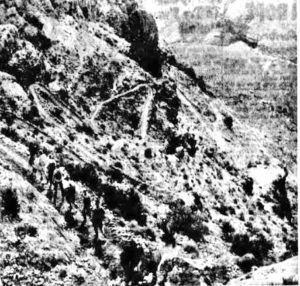

Workers were transported over to the south side of the Colorado River daily using the tram that was used for the wood. The men used five air compressors, jackhammers, and 40,000 pounds of blasting powder on a half mile section from Pipe Creek. Two to six hours of steady drilling was necessary to drill one blast hole. Twenty to 40 sticks of powder were used in a hole. “Two boys working alternately, a jack-hammer man and helper, were assigned to each hammer. At times in their work they were suspended from ropes and life belts.”

Workers were transported over to the south side of the Colorado River daily using the tram that was used for the wood. The men used five air compressors, jackhammers, and 40,000 pounds of blasting powder on a half mile section from Pipe Creek. Two to six hours of steady drilling was necessary to drill one blast hole. Twenty to 40 sticks of powder were used in a hole. “Two boys working alternately, a jack-hammer man and helper, were assigned to each hammer. At times in their work they were suspended from ropes and life belts.”

Drilling the decomposed granite areas were very difficult because it would crumble and cave in, causing drill bits to stick in the hole. “The powder man was very cautious about the amount of powder to use in this formation for fear of losing the trail bed.” Dangers of slides were constant. “If a stone fell off the side of the cliff, or any little unusual thing happened, the men were moved out. Sometimes the men were moved out because the supervisor would sense the danger that was near.”

During the winter of 1934, the biggest accident occurred. A cliff being worked on was very treacherous. “At one point three attempts were made to go around a cliff. Each time the trail was nearly completed, a slide would carry the whole thing off. The only serious accident during the entire trail construction occurred at this point. An unexposed talc seam separated the ledge from the cliff face. Three boys were working on a ledge. They were anchored by ropes. Then, without warning, the cliff slid off. Ropes supporting two of the boys snapped. They were carried with tons of rock down, down, toward the rushing river. When their descent was halted, they were within a few feet of the river. The two were rescued from a mass of debris and hurried on stretchers to the camp hospital located in the Phantom Ranch bunkhouse with a doctor and orderly. For a time it was feared their injuries would prove fatal, but they both recovered.” One decided he had had enough of the Canyon after he recovered. “Few camps had better medical care than the enrollees serving at the bottom of the Canyon.” With each incident, the men became more aware of the hazards and could better detect danger signs.

During the winter of 1934, the biggest accident occurred. A cliff being worked on was very treacherous. “At one point three attempts were made to go around a cliff. Each time the trail was nearly completed, a slide would carry the whole thing off. The only serious accident during the entire trail construction occurred at this point. An unexposed talc seam separated the ledge from the cliff face. Three boys were working on a ledge. They were anchored by ropes. Then, without warning, the cliff slid off. Ropes supporting two of the boys snapped. They were carried with tons of rock down, down, toward the rushing river. When their descent was halted, they were within a few feet of the river. The two were rescued from a mass of debris and hurried on stretchers to the camp hospital located in the Phantom Ranch bunkhouse with a doctor and orderly. For a time it was feared their injuries would prove fatal, but they both recovered.” One decided he had had enough of the Canyon after he recovered. “Few camps had better medical care than the enrollees serving at the bottom of the Canyon.” With each incident, the men became more aware of the hazards and could better detect danger signs.

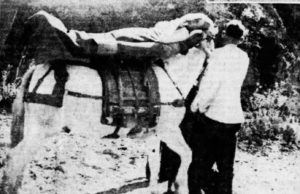

Other accidents occurred. The injured men were taken up the South Kaibab trail on specially constructed litters. A strong, fast mule name Old Jim was used as an ambulance. A pipe or canvas stretcher was placed on a pack saddle two feet by six feet. “A patient, with his blankets, was placed on the stretcher and secured by broad canvas bands.

Other accidents occurred. The injured men were taken up the South Kaibab trail on specially constructed litters. A strong, fast mule name Old Jim was used as an ambulance. A pipe or canvas stretcher was placed on a pack saddle two feet by six feet. “A patient, with his blankets, was placed on the stretcher and secured by broad canvas bands.

Man and stretcher then were lifted to the pack saddle and fastened on in such a position that the man’s head was directly above the mules ears and his feet over the animals tail. One man led the mule, two walked in front and two behind to steady the bobbing litter. Average time for the trail trip was four hours.” Over the years a total of 34 had to be transported out on mule litters.

Man and stretcher then were lifted to the pack saddle and fastened on in such a position that the man’s head was directly above the mules ears and his feet over the animals tail. One man led the mule, two walked in front and two behind to steady the bobbing litter. Average time for the trail trip was four hours.” Over the years a total of 34 had to be transported out on mule litters.

In 1935, twenty-three enrollees from Oklahoma issued a complaint that they were compelled to do dangerous work on the Grand Canyon cliffs. An investigation was conducted and it was reported that the young men had been sent home because they were “troublesome and refused to do any kind of work.”

In 1935, twenty-three enrollees from Oklahoma issued a complaint that they were compelled to do dangerous work on the Grand Canyon cliffs. An investigation was conducted and it was reported that the young men had been sent home because they were “troublesome and refused to do any kind of work.”

The reporting officer said, “in two years of trail building in the Grand Canyon, only two boys have been injured and their have been no fatalities. Our records show that more men are killed in CCC camps throughout the country by falling off trucks than in any other way. There are no trucks in the canyon. Our men are allowed to select the type of work they want. Of the 182 men in the canyon, only 64 are employed on trail construction. One of these is an Oklahoma boy who asked to run a jack hammer. We have competent foremen in charge and every precaution is taken for safety of the men.”

The reporting officer said, “in two years of trail building in the Grand Canyon, only two boys have been injured and their have been no fatalities. Our records show that more men are killed in CCC camps throughout the country by falling off trucks than in any other way. There are no trucks in the canyon. Our men are allowed to select the type of work they want. Of the 182 men in the canyon, only 64 are employed on trail construction. One of these is an Oklahoma boy who asked to run a jack hammer. We have competent foremen in charge and every precaution is taken for safety of the men.”

The River Trail was finally opened on January 20, 1936. A veteran muleskinner took the first mule train over it. “As a monument that will stand for generations as an accomplishment of the CCC, the River trail was built with tens of thousands of man hours.” Hopefully the next time you run on the trail, you will look carefully at their work and think of the hundreds of boys who worked on it.

The River Trail was finally opened on January 20, 1936. A veteran muleskinner took the first mule train over it. “As a monument that will stand for generations as an accomplishment of the CCC, the River trail was built with tens of thousands of man hours.” Hopefully the next time you run on the trail, you will look carefully at their work and think of the hundreds of boys who worked on it.

Entertainment

The young men needed entertainment while working for months in isolation down in the Canyon. They brought down a pool table to play. Part of it was too heavy for the mules. “At a company meeting, more than 100 volunteered to hike up the seven-mile trail and help carry the pieces down on foot. They set out on Saturday morning and by Sunday afternoon the last piece was in camp. Early Monday morning the table was installed and it was said to be the best investment the company every made”

The first motion picture ever shown at the canyon bottom, “The Terrible People” was shown in the CCC camp, attended by 105 men and guests from Phantom Ranch. The first movie machine they had was powered manually by a hand crank and had to be rewound after each toll of film was finished.

“Twice a week films provided by the army are packed into the canyon. They are silent, often ancient, yet eagerly awaited.” The camp superintendent said, “The boys enjoyed and appreciated this more than any one thing that could have been done for them in the way of recreational advantages.” The first sound picture shown at the recreation hall at Phantom Ranch 1935 was “Romance in Manhattan.”

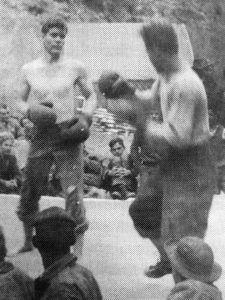

They also boxed, wrestled and played volleyball or football in their camp. A recreation hall/tent was put up equipped with picnic tables, benches, folding chairs, a ping-pong table and three stoves for heating. It was supplied with games such as checkers, chess, cards, dominoes, etc. Newspapers the boys received from home were placed on a reading table along with magazines and books.

They also boxed, wrestled and played volleyball or football in their camp. A recreation hall/tent was put up equipped with picnic tables, benches, folding chairs, a ping-pong table and three stoves for heating. It was supplied with games such as checkers, chess, cards, dominoes, etc. Newspapers the boys received from home were placed on a reading table along with magazines and books.

The blacksmith, George Shields, taught music lessons and established a band. Musical entertainment put on by the camp was enjoyed. He also directed a choral group. He led singing at church services and singalongs at company gatherings. One of the more accomplished groups was “The Seems Funny Orchestra,” They played for special parties and dances. At times there were special events or movies being held at the company stationed on the South Rim. Some would hike all the way up and back to participate.

A croquet course was also built. A public address system was installed so they could hear the latest popular music records played during meal times. Radio reception was impossible at the bottom of the canyon, so music came from playing records.

Enrollees who could not read or write were encouraged to attend educational classes put on by an educational adviser. Tentmates were enlisted to tutor them and took great pride in helping the boys. In addition to basic courses, other classes were provided in English, spelling, geography, and algebra.A library was established with books on many subjects. Even typewriters were brought done.

Other CCC work

The CCC did cleanup work and construction at Indian Garden. They removed Cameron’s structures there and built a new caretaker’s cabin, trail shelter, and mule barn with corral. They gave the Black Bridge a new painting since the existing paint had started to peel. It required 65 gallons of black paint, applied with a spray machine.

The CCC did cleanup work and construction at Indian Garden. They removed Cameron’s structures there and built a new caretaker’s cabin, trail shelter, and mule barn with corral. They gave the Black Bridge a new painting since the existing paint had started to peel. It required 65 gallons of black paint, applied with a spray machine.

They also constructed the Clear Creek Trail where ancient ruins were found. They built bridges across Bright Angel Creek, made the trail to Ribbon Falls, and put up stone walls that are still seen on the North Kaibab Trail. Up on the North Rim they constructed a ski/toboggan run and tennis courts that could be flooded in the winter for ice skating.

They also went to work obliterating the old abandoned “cable trail” that was replaced by the new Kaibab trail in the canyon above Black Bridge. “The trail was unsightly in that it was obvious that the terrain had been disturbed by man. The Park Service wanted all evidence of the disturbance hid from the view of park visitors.” Despite the good work, with a keen eye, you can still see evidence of the trail today.

Swimming Pool

The CCC built a swimming pool at Phantom Ranch. It was 72 feet by 40 feet and 19 feet deep. They had to remove hundreds of massive boulders that the creek had deposited during floods over thousands of years. The pool walls and floor were concrete and rock.

The CCC built a swimming pool at Phantom Ranch. It was 72 feet by 40 feet and 19 feet deep. They had to remove hundreds of massive boulders that the creek had deposited during floods over thousands of years. The pool walls and floor were concrete and rock.

A tourist watched the construction and said, “As if the 5,000 feet of the canyon weren’t deep enough, they’re digging another hole for a swimming pool!” Diverted water came from Bright Angel Creek. It would be the center-piece of Phantom Ranch for many decades. Deer would drink out of the pool as they journeyed through the area.

A CCC worker said, “The first time I saw Phantom Ranch the swimming pool was just completed. I remember diving into the water and finding little chunks of ice floating there. The temperature down there was about 105 so you can imagine the shock I received.”

The pool was used until 1972 when it became a maintenance chore, was overused, and without chlorine, experienced bacteria growth causing health problems. It was decided to get rid of it. It was filled up with many items including hand-carved doors, a piano, oil burning stoves, grills, pool table, and items from the old blacksmith shop.

Telephone Line

For the enrollees, communication with home was difficult. The most reliable way was by letter which took 4-5 days to arrive. A telephone line was constructed in 1922 with lines hung from trees. It supported about ten phones but could only have one conversation at a time and was very unreliable. If the line was working, it was in use both day and night. There was a telegraph office at Grand Canyon Village for a message to go out if taken up by the mule teamsters.

The abandoned telephone line that today is seen along the North Kaibab Trail was the CCC’s handiwork in 1934. The new line stretched 25 miles between the North Rim and the South Rim.

It first consisted of a single telephone line, hung from 600 poles of 2-inch galvanized pipe that were all brought down by hand. One of the workers wrote, “For a person to qualify for a job of this nature he would need a degree in engineering, the strength of a mule, the endurance of a camel, the surefootedness of a mountain goat and the tenacity of a bulldog.”

It first consisted of a single telephone line, hung from 600 poles of 2-inch galvanized pipe that were all brought down by hand. One of the workers wrote, “For a person to qualify for a job of this nature he would need a degree in engineering, the strength of a mule, the endurance of a camel, the surefootedness of a mountain goat and the tenacity of a bulldog.”

Constructing the line the “The Box” was very difficult. “Locating the right-of-way was a matter of finding a ledge wide enough for tow men to work and allow the telephone line to be strung up the canyon without toughing the cliff.” Work was dangerous going up Roaring Springs Canyon to the North Rim with all the talus slopes. “The men who drilled the holes were equipped with ropes anchored to solid rock projections that jutted out from the cliff. Utmost caution was exercised while stringing the lines down talus slopes for fear of rock slides causing a persons to go over a 1,000-foot cliff.”

In 1938 the poles were upgraded with a second circuit and new cross-arms. Over the years the line was unreliable because of storms in the winter and snow. In 1942 a “radiotelephone” started to be used for improved communications.

1936 Flood

In August 1936, a massive flash flood sent a wall of water down Bright Angel Creek that was said to be 16-feet high at one point through “The Box.” The night a rescue crew was sent down from the North Rim to search for some park employees that had not arrived at Phantom Ranch. The trail coming down Roaring Spring Canyon was totally obliterated in many places with huge boulders. By the time they reached Bright Angel Creek, the water had subsided, running normal. “The high water had made a boulder field out of the trail area.

In August 1936, a massive flash flood sent a wall of water down Bright Angel Creek that was said to be 16-feet high at one point through “The Box.” The night a rescue crew was sent down from the North Rim to search for some park employees that had not arrived at Phantom Ranch. The trail coming down Roaring Spring Canyon was totally obliterated in many places with huge boulders. By the time they reached Bright Angel Creek, the water had subsided, running normal. “The high water had made a boulder field out of the trail area.

They located the missing men at 1 a.m. on a ledge right before “The Box.” They were in bad shape, seriously cold, but were rescued by a warm fire and emergency whiskey. The flood destroyed the water pipeline going up to the North Rim. Damages were estimated at $50,000. Temporary water facilities were provided for the North Rim lodge and camp. The flood also damaged the North Kaibab trail along the creek and it was closed. CCC enrollees went to work repairing the damage.

Closing the Camp

The CCC also constructed trail shelters called Mile-and-a-Half House, Three-Mile House, Indian Garden Rest House, and River Rest House, which have provided many hikers with shade and a place to rest. By 1937 trail usage into the Canyon grew to about 20,000 people per year. After the CCC camp was removed, the CCC’s last project was to plant many cottonwood trees that are now enjoyed by those camping at Bright Angel Campground.

The CCC also constructed trail shelters called Mile-and-a-Half House, Three-Mile House, Indian Garden Rest House, and River Rest House, which have provided many hikers with shade and a place to rest. By 1937 trail usage into the Canyon grew to about 20,000 people per year. After the CCC camp was removed, the CCC’s last project was to plant many cottonwood trees that are now enjoyed by those camping at Bright Angel Campground.

In 1938 work took place to improve the trail from the bottom of the new Devils Corkscrew through Pipe Creek to the Colorado River. About 75 percent of the Pipe Creek Canyon trail work involved carving into the cliffs to raise the trail up above the high water mark. It was completed in 1939.

Snowbound on the North Rim

During the early winter of 1937-38, a large construction crew became snowbound on Christmas at a construction camp on the North Rim. They were holed up at the Bright Angel Lodge at the North Rim. The snow was so deep that snowplows failed to break a trail to the camp. A big rotary snowplow broke down trying to clear 20-foot drifts where others had been marooned at a ranch. A sled sent out also broke down. “Parts for the broken machines were ordered sent by airplane. The only plane at Grand Canyon airport was damaged when it was removed from its hangar and was unable to make the trip.” The alarming story was covered nation-wide.

During the early winter of 1937-38, a large construction crew became snowbound on Christmas at a construction camp on the North Rim. They were holed up at the Bright Angel Lodge at the North Rim. The snow was so deep that snowplows failed to break a trail to the camp. A big rotary snowplow broke down trying to clear 20-foot drifts where others had been marooned at a ranch. A sled sent out also broke down. “Parts for the broken machines were ordered sent by airplane. The only plane at Grand Canyon airport was damaged when it was removed from its hangar and was unable to make the trip.” The alarming story was covered nation-wide.

In February, still stranded, 15 desperate men fought their way through snowdrifts toward the the North Kaibab trailhead. They left behind at the lodge 14 others including two women, and a three-year-old child, who only had enough food for three more days.

In February, still stranded, 15 desperate men fought their way through snowdrifts toward the the North Kaibab trailhead. They left behind at the lodge 14 others including two women, and a three-year-old child, who only had enough food for three more days.

The 15 descended into the warmer canyon and arrived at Phantom Ranch on February 21, 1937, and the next day were take up to the South Rim on mules. The Utah Parks Company quickly organized a rescue party to bring out the other 17 on pack mules.

The 15 descended into the warmer canyon and arrived at Phantom Ranch on February 21, 1937, and the next day were take up to the South Rim on mules. The Utah Parks Company quickly organized a rescue party to bring out the other 17 on pack mules.

Two days later, the last of the stranded people arrived safely at Kanab, Utah, just before midnight. A large plow went in again and successfully arrived near the lodge. A light tractor reached them, bringing them 16 miles through the snow covered road and then automobiles brought them the rest of the way.

Treks across the Canyon

During the 1940s, most of the young men from the CCC went to defend the country fighting in World War II. There were not many daring rim-to-rim hikers during that time. Nearly all of the journeys across the Canyon involved mule rides. “Mulebacking is recommended for all but top conditioned hikers.”

A few hikers began to make the trek in multiple days and newspapers would make a big deal out of it. Tourists on the rim would “gawk” at unusual hikers who came out of the canyon up by foot. One hiker wrote in 1941, “Arrived at the top to amusement and amazement of visitors, who had been following our progress with interest and who roamed around us as we rested, snapping pictures as if we were a newly discovered Indian tribe or something.” A college hiking club at Flagstaff, Arizona made annual group hikes into the canyon for many years.

In 1949 Harry Brown, an employee of the Forest Service, said he ran what is believed to be the first double crossing in less than 24 hours.

In 1953, a group of six men and a ten-year-old boy from California split up in two groups, one starting from the North Rim and one from the South Rim. They each spent two days doing a rim-to-rim, meeting together camping at Phantom Ranch. They called their trip, “Operation Drag Out” and their local newspaper printed a big newspaper article about their “daring” trip. They claimed the trail was so narrow that if they would have met a mule train that it would have caused a big problem.

In 1953, a group of six men and a ten-year-old boy from California split up in two groups, one starting from the North Rim and one from the South Rim. They each spent two days doing a rim-to-rim, meeting together camping at Phantom Ranch. They called their trip, “Operation Drag Out” and their local newspaper printed a big newspaper article about their “daring” trip. They claimed the trail was so narrow that if they would have met a mule train that it would have caused a big problem.

![]()

By 1955 hiking into the canyon was being promoted with appropriate warnings about difficulty and heat. “A person can ‘pack a sack’ and descend the twisting Kaibab Trail on foot without guide or fee. However, the penalty for running out of energy within the canyon can be high. It is possible to telephone from any of several stations along the trail and have a mule sent to carry a person out, but the charge is high. ‘Travel light’ is a wise motto.”

A campsite was available to use at Roaring Springs with tent, cot, tables, and fireplace. In 1955, a third of the 2,444 Phantom Ranch guest descended into the canyon on foot. Slim Patrick and his wife operated Phantom Ranch. “They doctored many hikers for blisters and injuries as severe as sprained ankles. Most of the hikers requiring aid didn’t know what thery were getting into.”

Blind pioneer rim-to-rim hikers

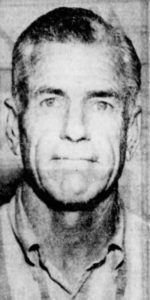

Charles Alexander Thornton (1912-1993) should be recognized as the founder of Grand Canyon rim-to-rim hiking in a day. He was born in Nogales, Arizona, on the Mexico border, south of Tucson, Arizona. When he was five years old, his mother died and he moved to Canada to be raised by relatives. In 1927, at the age of 15, he moved to Tucson, Arizona and graduated from Tucson High School. In the early 1930s, he operated a soda fountain in the downtown area. In the early 1940s he was hired as a salesman for a beverage company.

Charles Alexander Thornton (1912-1993) should be recognized as the founder of Grand Canyon rim-to-rim hiking in a day. He was born in Nogales, Arizona, on the Mexico border, south of Tucson, Arizona. When he was five years old, his mother died and he moved to Canada to be raised by relatives. In 1927, at the age of 15, he moved to Tucson, Arizona and graduated from Tucson High School. In the early 1930s, he operated a soda fountain in the downtown area. In the early 1940s he was hired as a salesman for a beverage company.

In 1947, he started to volunteer at the Arizona State School for the Deaf and Blind, and established a wrestling program. Two years later he was hired full-time by the school. When Thornton first came to the school there was no physical education program available for the blind students, so he organized it. A student remembered, “So many blind students would just sit on the mat or on the sidelines. He would always try to get them motivated because they were afraid and hadn’t been encouraged to try physical activity.” The Lion’s Club built a gym and friends donated equipment such as chin-up bars and exercise bikes. Thornton built a running track with special posts and rails to guide the boys as they ran. NBC aired a news segment on the unique track.

In 1947, he started to volunteer at the Arizona State School for the Deaf and Blind, and established a wrestling program. Two years later he was hired full-time by the school. When Thornton first came to the school there was no physical education program available for the blind students, so he organized it. A student remembered, “So many blind students would just sit on the mat or on the sidelines. He would always try to get them motivated because they were afraid and hadn’t been encouraged to try physical activity.” The Lion’s Club built a gym and friends donated equipment such as chin-up bars and exercise bikes. Thornton built a running track with special posts and rails to guide the boys as they ran. NBC aired a news segment on the unique track.

In 1953, Thornton established a hiking club at the school. Boys in the club became very fit hiking local trails in the mountains around Tucson and scaled some high mountains. Thornton came up with the idea for some of them to hike rim-to-rim across the Grand Canyon. In April,1956 Thornton had those interested run two miles each morning before breakfast on the special track. Thornton explained “In addition to keeping them in excellent physical condition, hiking develops their mental horizons, broadens their accomplishments and gives them a rewarding outdoors experience. They’re wonderful kids.”

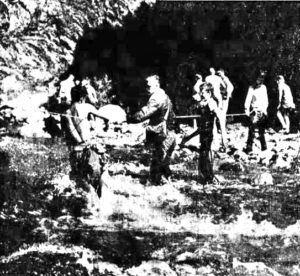

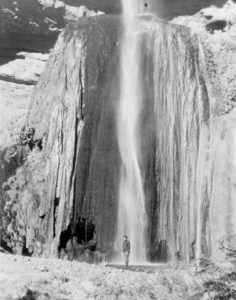

In late May, 1956, Thornton, his sighted 12-year-old son, and a photographer led two completely blind boys and four other partially blind boys down South Kaibab Trail, destined for the North Rim. It only took them two and a half hours to reach the Colorado River, where they crossed the Black Bridge. “Then they bathed their feet and patched their blisters on the banks of the Colorado.” By noon they reached Ribbon Falls, showered under the spray, and ate lunch. They had to ford Bright Angel creek six times. They rested at a power plant near Roaring Springs that furnished electricity for the North Rim and to the station to pump water up to the North Rim.

In late May, 1956, Thornton, his sighted 12-year-old son, and a photographer led two completely blind boys and four other partially blind boys down South Kaibab Trail, destined for the North Rim. It only took them two and a half hours to reach the Colorado River, where they crossed the Black Bridge. “Then they bathed their feet and patched their blisters on the banks of the Colorado.” By noon they reached Ribbon Falls, showered under the spray, and ate lunch. They had to ford Bright Angel creek six times. They rested at a power plant near Roaring Springs that furnished electricity for the North Rim and to the station to pump water up to the North Rim.

Thornton said that the boys had an excellent sense of balance, timing, and seldom stumbled. “Going down the trail, the completely blind keep in touch, usually hand on shoulder, with the man ahead. They follow well. They are used to hiking single file. Rough terrain holds no terrors for them. If the path becomes unusually difficult or hazardous, the leader sings out, and the blind place both hands on the hips of the man ahead.” Climbing up was more difficult and they used a rope. “Here the leader fastens a rope about his waist extending back on either side. The boys line up between the ropes, then they grasp the ropes with each hand, and skillfully respond to any command or movement of the leader.”

Thornton said that the boys had an excellent sense of balance, timing, and seldom stumbled. “Going down the trail, the completely blind keep in touch, usually hand on shoulder, with the man ahead. They follow well. They are used to hiking single file. Rough terrain holds no terrors for them. If the path becomes unusually difficult or hazardous, the leader sings out, and the blind place both hands on the hips of the man ahead.” Climbing up was more difficult and they used a rope. “Here the leader fastens a rope about his waist extending back on either side. The boys line up between the ropes, then they grasp the ropes with each hand, and skillfully respond to any command or movement of the leader.”

The last five-mile stretch was of course grueling. They arrived at the top at 7 p.m. for an impressive 12-hour crossing. “As Raymon Mungaray, age 19, panted to the top, he paused, took a deep breath that burst into a happy grin, clapped his companion on the shoulder and exclaimed, ‘Boy, what an experience! We’ve sure got a lot to tell the fellows when we get back.”

The last five-mile stretch was of course grueling. They arrived at the top at 7 p.m. for an impressive 12-hour crossing. “As Raymon Mungaray, age 19, panted to the top, he paused, took a deep breath that burst into a happy grin, clapped his companion on the shoulder and exclaimed, ‘Boy, what an experience! We’ve sure got a lot to tell the fellows when we get back.”

The pioneer rim-to-rim 1956 hikers were: John Tsosie (1937-1998),18, Ennis Sumpter (1939-1963), 16, Evans Honkoinewa, Richard Ferguson (1939-2009) 17, Jerry Fields (1940-2005), 16, Raymon Mungaray (1937-2016), 19, Willie Thornton, 12, and Charlie Thornton, 43. In 1958, Thornton led a second group of eight boys from the school across again and finished in eleven hours.

In 1959, sadly Thornton was fired from the school after 10 years of employment because of a difference of opinion over administrative matters. The public was outraged and sent in many letters of protest into the newspaper. “Mr. Thornton has become a second father to the boys.” Boys went to ask why, but the superintendent only said that Thornton “would not be returning under any circumstances.”

In 1959, sadly Thornton was fired from the school after 10 years of employment because of a difference of opinion over administrative matters. The public was outraged and sent in many letters of protest into the newspaper. “Mr. Thornton has become a second father to the boys.” Boys went to ask why, but the superintendent only said that Thornton “would not be returning under any circumstances.”

![]() Thornton appealed. A closed hearing was held with deliberations for four hours, and the firing was upheld because of “insubordination.” Thornton did not attend the appeal hearing because he wanted it to be open to the public. In later years Thornton said he was fired because he did not have a college degree, although he suspected that envy might have been involved. “The programs he developed for the blind children had surpassed those programs for the deaf and that caused a rift.” The school soon dismantled all that Thornton had built, including the gym and the track.

Thornton appealed. A closed hearing was held with deliberations for four hours, and the firing was upheld because of “insubordination.” Thornton did not attend the appeal hearing because he wanted it to be open to the public. In later years Thornton said he was fired because he did not have a college degree, although he suspected that envy might have been involved. “The programs he developed for the blind children had surpassed those programs for the deaf and that caused a rift.” The school soon dismantled all that Thornton had built, including the gym and the track.

But the 1959, the Grand Canyon hike went on with seven boys from the school. “While the boys were doing a lot of shouting and talking back and forth during the first half of the trip, they’re quiet and businesslike on this last section. The pace had slowed down quite a bit to about a 2 mph average.” The boys took very short rests while going up the steep North Kaibab Trail. They were constantly figuring out how long it would take to get to the top, hoping to break their eleven hour record. Two received permission to push on ahead and came in under 12 hours.

The new Southern Arizona Hiking Club, from Tucson, Arizona, had joined by 1960. Twenty-two hikers participated including seven blind boys from the school. Some of the boys had previously made the trip. It was thought to be the largest group at that time to ever hike across the Canyon. Thornton said of the boys, “They seem to feel, if they can cross the Grand Canyon on foot in one day, they can do almost anything.”

That year they were all together at Ribbon Falls at the hottest time of the day and then some faster hikers went on ahead. “It was difficult to keep some of the more ambitious boys in check as the distance to the top got shorter. Two could stand the slow pace set by Thornton no longer. They lit out for the top at a run and despite being more than a mile behind, they passed all the hiking club members but two.” The hiker first to finish that year was Dave Gross, in 9:35. They all finished by 13 hours.

That year they were all together at Ribbon Falls at the hottest time of the day and then some faster hikers went on ahead. “It was difficult to keep some of the more ambitious boys in check as the distance to the top got shorter. Two could stand the slow pace set by Thornton no longer. They lit out for the top at a run and despite being more than a mile behind, they passed all the hiking club members but two.” The hiker first to finish that year was Dave Gross, in 9:35. They all finished by 13 hours.

After returning home, a participant was questioned why in the world would anyone take blind kids to see the Grand Canyon. He wrote, “I submit that those blind boys saw more than do half the hurrying tourists who promenade along the rim-side patio of Bright Angel Lodge. For I know that those boys smelled the fresh fragrance of pine trees in the chilly morning breeze, heard the whir of wind through the junipers, tasted the hot dust along the downhill trail, shivered through waist-deep crossings of icy Bright Angel Creek, and heard the muffled rumble of the silt-laden river below as they tramped across the narrow footbridge leading to the cottonwood-shaded oasis of Phantom Ranch. In crossing the mile-deep chasm on foot, they achieved something few sighted visitors ever will equal.”

After returning home, a participant was questioned why in the world would anyone take blind kids to see the Grand Canyon. He wrote, “I submit that those blind boys saw more than do half the hurrying tourists who promenade along the rim-side patio of Bright Angel Lodge. For I know that those boys smelled the fresh fragrance of pine trees in the chilly morning breeze, heard the whir of wind through the junipers, tasted the hot dust along the downhill trail, shivered through waist-deep crossings of icy Bright Angel Creek, and heard the muffled rumble of the silt-laden river below as they tramped across the narrow footbridge leading to the cottonwood-shaded oasis of Phantom Ranch. In crossing the mile-deep chasm on foot, they achieved something few sighted visitors ever will equal.”

Anita Harlan, 22, studying anthropology at the University of Arizona, was the only woman in the 1960 rim-to-rim group and is believed to be the first woman to complete a rim-to-rim hike in a day. Harlan, who grew up in Utah said, “I’ve hiked with men so long that they are used to me. There just aren’t many women who like to go hiking, I guess.” As usual at the time, reporters were curious what a woman wore. “She hiked in beige Bermuda shorts, a pink silk blouse and hiking boots. She selected the coolest attire without worrying about protection from the underbrush.” Her husband went along too. The two spent most of their spare time hiking together. The climb up to the North Rim was very slow, but she finished her single crossing in ten hours.

First double crossings (R2R2R) in a day.

In 1961, because Thornton could no longer train the boys from the school for the Blind, their association with the annual rim-to-rim hike came to an end. He said, “Keeping their interest and enthusiasm high had become too complicated.” The Southern Arizona Hiking Club in Tucson, founded by Pete Cowgill, can be credited for keeping it going and blazing the trail into double crossing runs. Fourteen club members hiked that year including one blind graduate from the school. Two older hikers, Bob Ward, 45, and Vaughn Short (1923-2010), 42, finished a single crossing in just over 10 hours.

In 1961, because Thornton could no longer train the boys from the school for the Blind, their association with the annual rim-to-rim hike came to an end. He said, “Keeping their interest and enthusiasm high had become too complicated.” The Southern Arizona Hiking Club in Tucson, founded by Pete Cowgill, can be credited for keeping it going and blazing the trail into double crossing runs. Fourteen club members hiked that year including one blind graduate from the school. Two older hikers, Bob Ward, 45, and Vaughn Short (1923-2010), 42, finished a single crossing in just over 10 hours.

During this hike, Eber Glendening (1934-1997), a civil engineer, and Bill Faust accomplished the first double crossings to “prove that it could be done.” In the heat of mid-June, they stopped at each Bright Angel Creek crossing to dunk their heads in the water. They had stashed some food and a flashlight at Phantom Ranch, but it all was stolen by the time they returned. Glendening said, “I was so mad that if those thieves had been around I’d have tossed them all into the Colorado River.”

During this hike, Eber Glendening (1934-1997), a civil engineer, and Bill Faust accomplished the first double crossings to “prove that it could be done.” In the heat of mid-June, they stopped at each Bright Angel Creek crossing to dunk their heads in the water. They had stashed some food and a flashlight at Phantom Ranch, but it all was stolen by the time they returned. Glendening said, “I was so mad that if those thieves had been around I’d have tossed them all into the Colorado River.”

Some tourists generously invited them for a fish dinner. “Between us, we had split one can of beans and one can of pineapple and we were so hungry we would have eaten anything that moved.” They rested for an hour and a half and then pushed back up to the South Rim. Reaching the Tonto Plateau, they had to talk each other onward and upward, and stopped every mile for a rest. “It would take a half dozen wobbly steps before they got their hiking legs back. Glendening further added, “When we slipped or stumbled over a waterbar, we couldn’t see because of the darkness, we tried to fall toward the inside.” They finished at 1:10 a.m. for 20:40. “We’ll never do it again, but we’re glad we did it once to prove it could be done.”

Two others from the club finished a double crossing in 1962, Ted Marley (1927-2014), and Joyce Wickham. Marley did it with a lighted cigarette hanging out of his mouth. Two students from the University of Arizona by the name of Bachus and Rhomsburg also accomplished it. The best time up to that point was about 19 hours.

In November, 1963, Allyn Cureton, of Williams, Arizona lowered the fastest known rim-to-rim run with a time of 3:56, beating his previous best of 4:15. It was written in the newspaper, “With apt promotion, the run through the mile-deep chasm could become a unique sporting competition.”

On Memorial Day, 1964, Charlie Thornton, age 52, ran a double crossing (R2R2R). He had always been the guide for the group and wondered how fast he could run across. He reached Phantom Ranch in 1:20 and continued strongly on. His first crossing took about 6:30. He rested for a half hour on the North Rim and then ran back down and reached Phantom Ranch at the 11:55 mark. There he filled his two canteens. His nourishment was a few caramels, some prunes and honey. After resting another half hour he continued.

he said “By this time, the South Rim seemed to have receded at least 100 miles. I have never seen so many hikers in all my trips through the canyon. I must have met at least 100, many of them Boy Scouts. Now I really had to grit my teeth to keep going. A thousand times I said I would never try it again. I knew that if my legs didn’t turn to rubber, I would get out by midnight.” He reached to the top at 9:25 p.m. for a time of 15:55, which was the fastest known time at that time. He signed the register and plopped down on an air mattress in a waiting camper. He said, “My last thought before drifting off to sleep was how long it will be before I’ll try it again.”

Boy Scouts

By the early 1960s, many Boy Scouts started to hike down into the canyon or rim to rim to earn special badges or qualify for the hiking merit badge. Howard Clark, age 12, from Buckeye, Arizona, hiked north to south across the Canyon during the heat of late July in 1926 with his brother and father. The temperature at the bottom was 114 degrees but they were able to finish in 13 hours.

By the early 1960s, many Boy Scouts started to hike down into the canyon or rim to rim to earn special badges or qualify for the hiking merit badge. Howard Clark, age 12, from Buckeye, Arizona, hiked north to south across the Canyon during the heat of late July in 1926 with his brother and father. The temperature at the bottom was 114 degrees but they were able to finish in 13 hours.

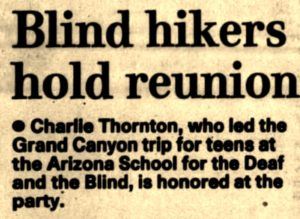

Blind hiker reunion

In 1992, a reunion of the first group of blind rim-to-rim hikers was held in Tucson, Arizona. “Ghosts of bubbly teen-age boys hiking across the Grand Canyon danced across the memories of about 30 people who gathered.” Charlie Thornton, age 80, who had recently went through heart surgery was honored.

In 1992, a reunion of the first group of blind rim-to-rim hikers was held in Tucson, Arizona. “Ghosts of bubbly teen-age boys hiking across the Grand Canyon danced across the memories of about 30 people who gathered.” Charlie Thornton, age 80, who had recently went through heart surgery was honored.

Richard Ferguson, 53, was 17 when he went on the hike. He said, “It was a challenge. It was physically very tiring, but mentally very exciting. Charlie wanted us to do these kinds of things so we could be equal to sighted people who had these opportunities available to them. We never had the opportunity before Charlie. He gave me a lot of confidence and helped me learn to meet new people and try new things.”

About the blind school, Thornton sadly said, “Now it’s all gone. They’ve ripped up the gym and the track and there’s a new building up now. There’s no sign of me ever being there anymore.” But his students were living monuments to his presence. They were truly the pioneers of Grand Canyon rim-to-rim hikers in a day, and started it all.

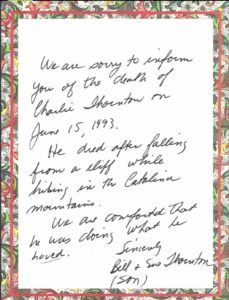

About a year and a half later, in June, 1993, Thornton went missing after he failed to return from a morning hike in the Santa Catalina Mountains above Tucson, Arizona. His car was found in the foothills. Sadly, his body was found at the bottom of a 40-foot dry waterfall. His hiking pack and water bottle was found at the top of the fall. A nice tribute was written about him in the Tucson newspaper. “He did more for those kids than anyone had ever done before.” Charlie Thornton was truly the father of Grand Canyon rim-to-rim hikes in a day.

About a year and a half later, in June, 1993, Thornton went missing after he failed to return from a morning hike in the Santa Catalina Mountains above Tucson, Arizona. His car was found in the foothills. Sadly, his body was found at the bottom of a 40-foot dry waterfall. His hiking pack and water bottle was found at the top of the fall. A nice tribute was written about him in the Tucson newspaper. “He did more for those kids than anyone had ever done before.” Charlie Thornton was truly the father of Grand Canyon rim-to-rim hikes in a day.

Please consider a donation to Utah Ultras LLC (Davy Crockett’s LLC) to help keep these episodes coming.

Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim Series

- 46: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 1 (1890-1928)

- 47: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 2 (1928-1964)

- 48: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 3 (1964-1972)

- 49: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 4: Aiken Family

- 50: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 5: The Races

- 135: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 6: Early Guides

- 136: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 7: Prof Cureton

- 137: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 8: Kolb Brothers

- 138: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 9: Phantom Ranch

Sources

- 1928 – A Bridge Worthy

- Bright Angel Trail

- Jouis Lester Purvis, The Ace in The Hole: A Brief History of Company 818 of the Civilian Conservation Corps

- Honolulu Star-Bulletin (Hawaii), Feb 20, 1928

- Arizona Daily Star (Tucson, Arizona), May 8, 1928, Jun 3, 1956, May 10, Jun 10, 1959, Jun 19, 27, 1960, Jun 18, 1962, Jun 21, 1964, Apr 11, 1965, Feb 13, 1972

- The Lost Angeles Times (California), Feb 9, 1929

- The Salt Lake Mining Review (Utah), Jan 15, 1929

- The Perry County Democrat (Bloomfield, Pennsylvania), Nov 6, 1929

- Los Angeles Evening Express (California), Jan 21, 1930

- Greeley Daily Tribune (Colorado), Mar 14, 1930

- Arizona Republic (Phoenix, Arizona), May 13, 1930, Aug 1, 1932, Oct 25, 1933, Mar 11, 1934, Aug 9, 1936, Jun 16, 1941, May, 28, Jul 16, 1952, Jun 8, 1958, Jul 31, Nov 13, 1963, Oct 21,28, 1974, Dec 15, 2007

- General Information Regarding Grand Canyon National Park, National Park Service, 1933

- Ames Daily Tribune (Iowa), Aug 15, 1933

- The Spokesman-Review (Spokane, Washington), Jun 16, 1934

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Jun 27, 1934

- The San Bernardino County Sun (California), Nov 16, 1935

- Reno Gazette-Journal (Reno, Nevada), Aug 21, 1936

- The Hanford Sentinel (California), Feb 22, 1937

- The Daily Herald (Provo, Utah), Feb 22, 1937

- The Salt Lake Tribune (Salt Lake City, Utah), Feb 24, 1937

- The MIami News (Florida), Jan 7, 1940

- The Bakersfield Californian, Jun 22, 1953

- Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, New York), Feb 27, 1955

- Tucson Daily Citizen (Arizona), May 7, 1959, Dec 28, 1992, Jun 17, 1993