Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 36:04 — 44.8MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

Part 4 of the Rim-to-Rim History Series. See also Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3

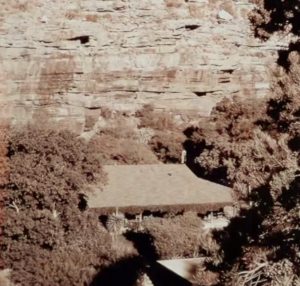

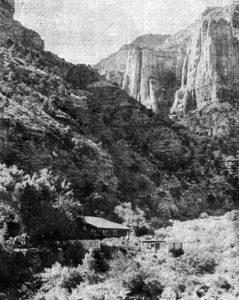

For anyone hiking or running rim-to-rim, most people will usually stop at a location about a mile below Roaring Springs that today is called the Manzanita Rest area, named after a creek coming down a small nearby side canyon. But the name and the rest area are a fairly new, a 2015 creation. Newer visitors have no idea that there is a rich history that took place at that location from 1973-2005.

| There are now more than 100 stories like this on the Ultrarunning History Podcast. Subscribe today! |

Bruce Aiken’s early years

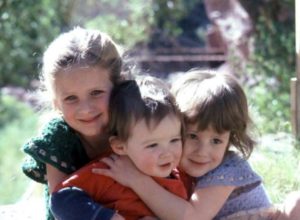

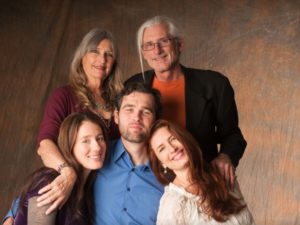

Bruce Aiken was born September 10, 1950 in New York City’s Greenwich Village to Richard and Margaret Aiken. He was the second of a family of five boys.

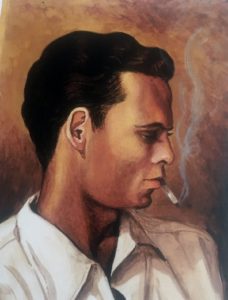

His father, Richard Little Aiken (1918-1997) grew up in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania where his father was a lawyer. Richard graduated from the Carnegie Institute of Technology in 1940, in theatre. He worked as a sports announcer for a local radio station and an actor. Following Pearl Harbor, Richard enlisted in the Navy, and became a naval aviator. He met Margaret during the war and afterwards they married and settled in Greenwich Village, New York City, where all their children were born. There, he worked for NBC as a television producer.

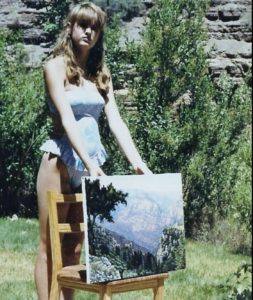

Margaret Davis Aiken (1924-2003) was born in Las Cruces, New Mexico, raised in Arizona along the Mexican border, where her father was an immigration inspector. During the Great Depression her family moved to Phoenix, Arizona where she studied art at Arizona State University. During World War II, she served in the navy women’s reserve as a WAVE in Santa Ana, California, where she met Richard. Margaret became a very accomplished artist. Her paintings were widely shown in New York, Florida, and at the Grand Canyon.

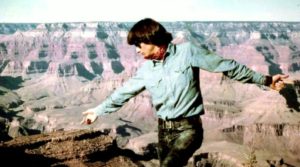

The family moved to Long Island where young Bruce started to draw and paint with his mother. The family often went on vacations to Arizona, to visit his grandparents and cousins. A 1963 visit to the Canyon had a deep impact on young Bruce.

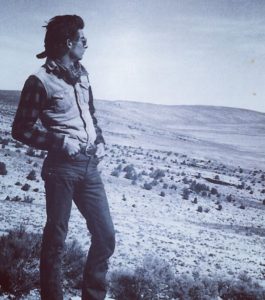

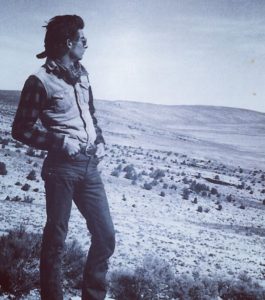

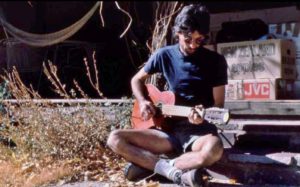

In 1968, Bruce graduated from high school and was voted “most talented.” Following in his mother’s footsteps, he was interested in art and enrolled in New York’s prestigious School of the Visual Arts. His father wanted him to go into advertising because he believed that was where the money was, but Bruce wanted to be an artist. Bruce said, “I suppose he was trying to help, but I think he was too domineering, too demanding and too unwilling to hear or understand what I was trying to do.” This caused a rift between the two that would last for years.

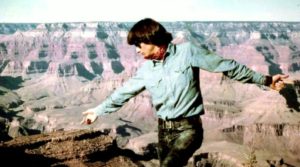

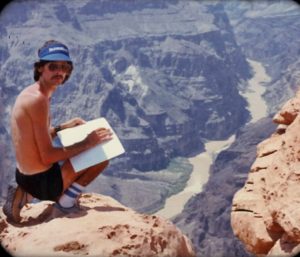

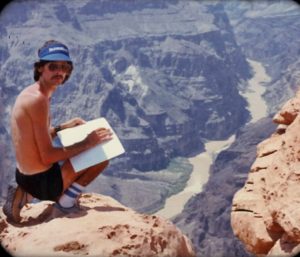

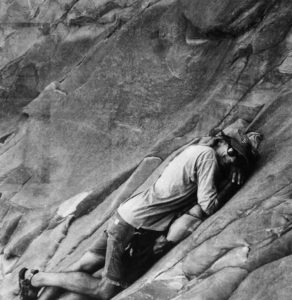

In November 1970 Bruce hiked down into the Grand Canyon for the first time to Phantom Ranch. He also hiked in many other places throughout northern Arizona and said, “My goal was to embark on a life that was beautiful, dynamic, and as above average as possible.”

Move to the rim of the Canyon

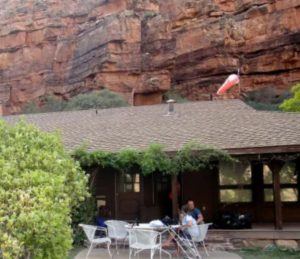

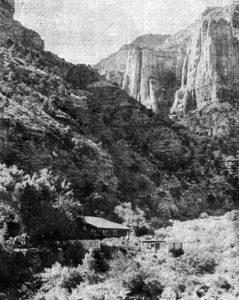

The only people allowed to live in the park at that time were Park employees, so a month later in April 1972, he hired with the National Park Service to work on the trail maintenance crew at the North Rim. He visited Roaring Springs down the North Kaibab Trail and was captivated by a house there. He said, “There was a white picket fence and a large porch fronting a white clapboard rambler whose cedar shake roof was covered with moss. I didn’t know how to respond, it was so stimulating, so exciting. It spoke to my heart. It was what I was looking for.”

Seasonal part-time caretakers would live in the two-bedroom pumphouse, maintaining the system and nearby trails. Stanley and John Brown from Kanab, Utah spent time there in the 1940s. The water system would be shut down for the winter, but the Browns lived down where it was warm and watched over the facilities on the North Rim. Herm Pollock of Bryce Canyon fame also spent time there with his family.

Once the Trans-Canyon Pipeline was finished in 1971, sending water also to the South Rim, it was soon determined that a full-time water system manager would be needed to watch over the system and do the constant repairs needed. In 1972 when Bruce first visited there while on the trail crew, Pollock was working at Roaring Springs, getting ready to retire.

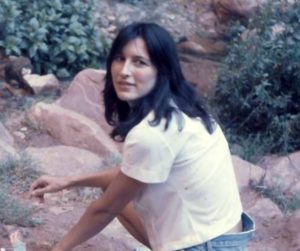

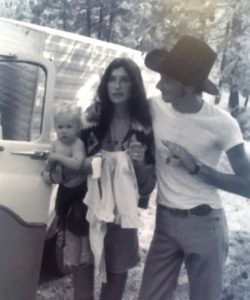

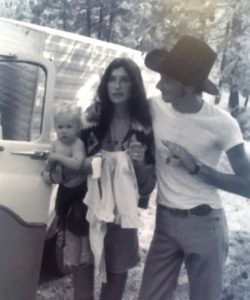

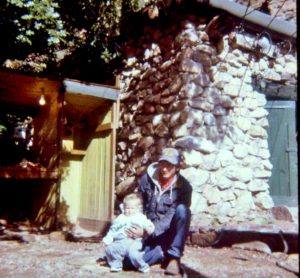

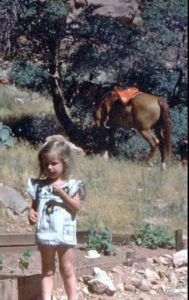

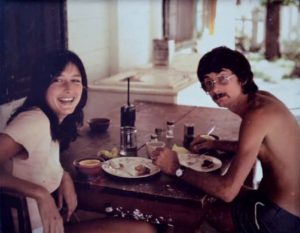

In the fall of 1972, Bruce returned to college, attended The University of Arizona in Tucson, and soon married Mary. He wasn’t happy going to school and convinced Mary to follow his dream and head back to the Grand Canyon. In 1973, he hired on with the general maintenance crew. Bruce, Mary, and their infant daughter Mercy, moved to the North Rim and lived in a cabin.

Bruce got to know Wendell Gifford Seegmiller (1921-1981), who maintained the water and electrical system at Roaring Springs during the spring of 1973. Bruce saw his chance to fulfill his dream to live at Roaring Springs when he realized the Park Service would be hiring a full-time water system manager and that Seegmiller would likely leave for another position. Bruce learned some about the system from Seegmiller and when the job became open, he somehow convinced the National Park managers that he had the mechanical background to do the job. He fooled them and got the job in July 1973.

Bruce said, “I don’t think Mary knew what to expect when I told her we were moving to the bottom of the Canyon. I think she was in shock. I just knew that I could think of no other place I would rather live.” Mary, who grew up in Seattle had always figured that she would end up living near the ocean.

Move to Roaring Springs

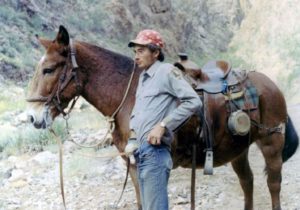

In 1973, the Aikens descended 5.5 miles and 4,000 feet on mules with their belongings and moved into the pumphouse. Mary thought, “’Where is this guy taking me now?’ I thought it was really amazingly beautiful but in the back of my mind I was thinking, ‘We won’t be down here very long.’”

Bruce was worried about his new job and said, “I was terrified that I might not live up to my job, which included fixing pipeline breaks. I didn’t even know which way to unscrew a nut when I started out, so I was consumed with figuring out how to test water samples and maintain and repair the pumps. I had to fool myself into believing I could do it, and then I had to do it.” He poured over blueprints to figure out what to do if the pumps broke down. Two others initially assisted him. “We had one bedroom and this baby, with two other guys working and living there.”

Water pipeline duty

Seegmiller stayed on for a time at the North Rim in a maintenance position. He helped Bruce learn but left in 1974 with a big farewell party at the North Rim attended by 35 Park employees. As a memento, he was given a section of the water pipeline and a beautiful drawing of the Pumphouse.

On off months, the family would leave the Canyon and spend most of their time at the South Rim, but eventually also had a home in Ajo, Arizona, where in 1975 Bruce worked the winter months at nearby Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument.

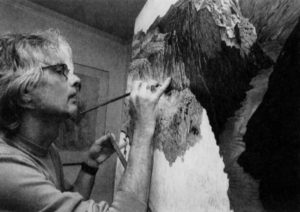

Bruce turns to art

Once when Bruce needed some art supplies, he started out early in the morning, ran down to Phantom Ranch, crossed the river and hiked up to South Rim. He obtained what had been delivered and then drove all the way around to the North Rim and descended back home by night.

Life in the Canyon

Life was simple and amazing for the family at Roaring Springs. Bruce said, “I had never been a guy who cared about shopping, or movie theaters, or crowds. Life in the Canyon got better every year.” They of course had no TV and mail came only every two weeks, but they could listen to three AM radio stations, only when they faded in at night. About the many visitors that passed by on the trail, Bruce said, “I knew they are going to ask me if I lived here, how I got my groceries, and whether or not I ever get bored. So, I always started right off with those three responses.”

It took Mary about three years to totally feel comfortable living down in the canyon, but one day while walking by the cliffs with the light streaming in, she suddenly felt a part of it. She said, “Wow, I’m so lucky. I never want to leave here. To know it is to love it. It has made me strong living here, inside and out.” She also said, “I don’t tell strangers that I live at the bottom of the Grand Canyon, it just confuses them.”

The scorpion emergency

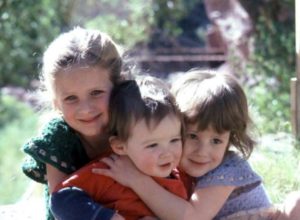

The Aikens were always fearful of what would happen if they experienced an emergency so far from help. They had a phone line but at times it would be out for weeks. One hot night in June, 1976, the two little girls were sleeping in the front yard on a mattress. Suddenly, at about 11 p.m., little Shirley let out a blood-curdling scream.

“Mary bolted out their door and grabbed her toddler. She looked her over feverishly. What could have spurred a scream like that? Mary found no obvious trauma. But Shirley continued to howl in pain. Bruce searched the mattress and yard nearby. Nothing. Even so, he suspected the unseen culprit. Shirley had been stung by a scorpion.”

“Shirley’s crying had become uncontrollable. Her wails emerged in crescendo waves of intensity as venom circulated through her tiny, twenty-five pound body. She acted agitated, restless and inconsolable. Abruptly she launched into a grand-mal seizure. She bit her tongue. Hard. Blood and saliva foamed at the corners of her mouth. Her entire body stiffened and she arched her head and neck backward for more than an hour, crying uncontrollably in between seizures.”

Wayne Ranney, age 22, was a ranger at Cottonwood Campground, about 1.5 miles down the trail. He was called by Dispatch and immediately sprinted out his door and up the trail to try to help. He knew the Aikens well. They fed him dinner nearly every night. He arrived about 25 minutes later where Mary was an emotional wreck and little Mercy was terrified looking at her little sister’s condition. Shirley had a high fever that they treated with ice packs. She continued with the seizures which sent panic through her parents. They all prayed hard.

At about 3 a.m., things improved, and the seizures stopped. Dawn arrived at 4:45 a.m. A helicopter landed and quickly flew Bruce and Shirley to the Grand Canyon Clinic on the South Rim. Mary stayed home with Mercy. Little Shirley received appropriate shots and by 8 a.m. she was out of danger.

Mary recalled, “After the scorpion bite, I started to think, ‘Am I a responsible parent? Should I get them out of the canyon?’ But Bruce talked me out of it. He said there were dangers everywhere.”

Playing in the Canyon

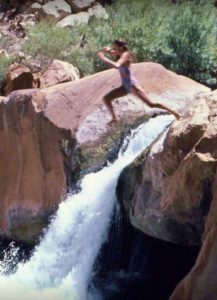

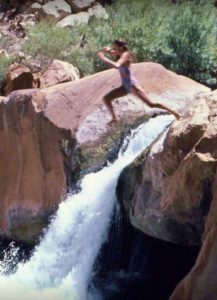

Up the creek from their home they dammed an area, making a little swimming pool for the family to enjoy on the many hot days. In later years, when the children were older, they swam at a place on Bright Angel Creek they named “Splitrock.” It was between their home and Cottonwood Campground at a very distinct waterfall that you can’t miss. At this swimming hole, they would leap off twenty feet into a 14-foot deep pool below. Later in the 1990s a big flood reconfigured the boulders around that area.

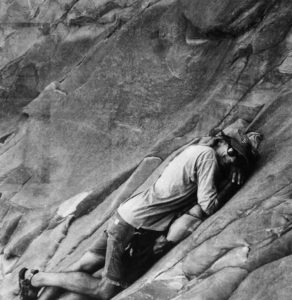

At times, the family would sleep on the Roaring Spring helipad and watch the stars. “And during the first monsoon rains, the kids danced for joy there. Manzanita Canyon was our backyard. The kids built forts there and climbed the walls where they discovered prehistoric ruins.”

A de-sanding operation was added to the water system in 1978, removing sand from the water that entered the pipeline in the caves above. A permit from the state was needed to discharge it back into the creek.

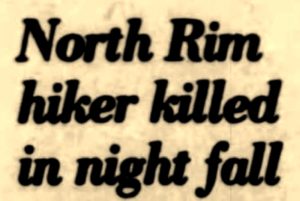

Deaths and Injuries

A new home

Bruce was given permanent employment status with the Park. That year the pipeline became even more important and started to also provide water for the town of Tusayan on the South Rim. More storage tanks were needed.

Lemonade Stand

In 1980, Mercy, age 7, set up a lemonade stand beside the trail for donations. The stand was such a popular success and lucrative that it lasted for years. Hikers would mention to others they passed that there was a lemonade stand just around the corner. They thought it was a joke, but there it appeared. Soon their lemonade stand became famous. If the kids weren’t out, people would walk up to the house and knock on the door. “Thankful hikers plunked change, $20 bills, sometimes granola bars and candy (the children’s personal favorite) into the can.” The record one-day haul was one Memorial Day, about $90. The children would constantly invite guests for dinner nearly every night.

Many of Silas’ earliest memories were of hikes to the rim and back, undertaken every two or three weeks. He said, “The rules were simple: You were carried, usually by Mom, until you turned 3. After that, you’re were on your own. We just hiked because it was part of living where we did. My mom was great because she would always walk with the slowest one.”

Homeschooling

Mercy further explained, “We had piles and piles of books, and I read and read and read. Nancy Drew books, books by Louis Lamour, books like ‘Gone with the Wind.’ It got to the point where my mom limited me to one book a day.”

Adventures in the Canyon

Silas said, “We would end up way up on the side of some cliff. We’d look down at the house, see my mom down there and wave. We’d make our way home when we got hungry. If not, we’d stay out.”

Mercy recalled, “I thought our lifestyle was completely normal. I thought everybody got their groceries packed in by mule or flown in by helicopter. I thought it was perfectly normal to get up in the morning, hike up the creek, stop at the swimming hole and then lie on the rocks looking up at the Grand Canyon. I thought it was normal to sleep out on the heliport every night, listening to the water flow by.”

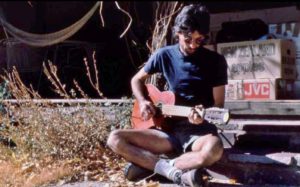

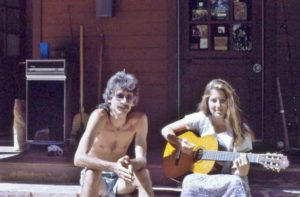

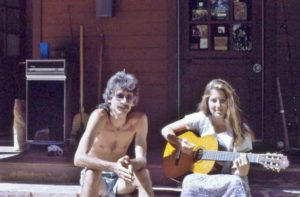

Mary said, “Down in the canyon it felt like camp. We’d bake bread, go hiking and swimming, and in the evening, we would break out the guitar and sing songs.”

They would at times hike up to the North Rim to play in or watch an evening ballgame with park and lodge employees and then hike all the way back home down in the dark.

When asked if the kids missed out on normal life, Bruce replied, “Yeah, but you know, you can’t have everything. The kids that lived in town didn’t have what my kids had. They had nature, full connection to nature, fabulous free reign.”

Visitors

Food arrived regularly for the family, either by rangers or helicopters. Bad weather shut down the pipeline at times and interrupt helicopter deliveries. Tired hikers carrying too much weight often dropped off protein bars. They rarely had a shortage of granola or trail mix.

Mary explained how they shopped. “In the beginning, we used to go up to Utah and shop and then we’d pack it in on mules. Then the park service started flying a helicopter all the time. So we would just coordinate with a flight. We’d hike to the North Rim, drive to Flagstaff, shop, then drive to the South Rim, and weigh it for helicopter delivery. Then we drove back to the North Rim or hiked down from the South Rim. At the very least, it was a two-day affair.”

Mercy remembered, “We spent lots of time exploring the side canyons around our house. But some of the most fun we had was with the hikers who came by our house. Sometimes we would tell hikers we were living in a commune. Or we’d dress up in weird outfits and act like it was perfectly normal dress for people living in the Canyon.”

She continued, “One of my favorite things was to take eggs out of a carton and lay them on plants along the trail, and then tell hikers they were real egg plants. Sometimes my sister and I would tell people we caught fish with our bare hands and ate them raw, and some of them believed us.”

The children learned a lot from their visitors. They heard about life in Sweden, Germany, South Africa, Australia, and many other countries. Silas later recalled, “When people found out about my childhood, they’d always say, ‘How was it, growing up so sheltered?’ Are you kidding? We didn’t have to go out into the world, because the world came to us.”

Years later, Shirley recalled, “Our parents tried really hard to give us a natural, normal upbringing, with a schedule and a routine, making sure we had social contact by inviting people down. We had friends coming down, and friends of friends, and cousins. Hikers we knew from before and friends of those hikers. It was a huge web of people who visited us. People expected that I grew up socially awkward as if I lived in a cave. In fact, it was the opposite.”

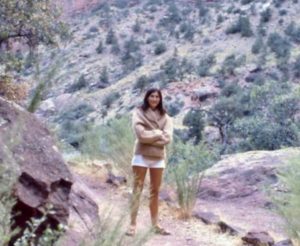

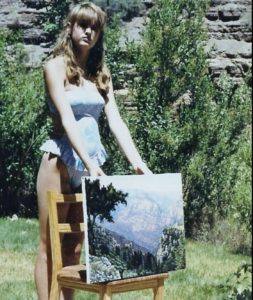

Bruce’s mother, Margaret was a regular visitor at Roaring Springs. She spent 1975 and 1976 summers living at Roaring Springs with them. In August 1981, she exhibited her Grand Canyon paintings in a joint show with Bruce at the Grand Canyon Visitor’s Center and El Tovar Hotel.

Winter crossings of the Grand Canyon became popular for a time. Adventuresome athletes would cross-country 40 miles from Jacobs Lake to the closed North Rim and then pack up their ski gear for a hike across the Canyon. Ranger Woody Harrell explained, “By the time many of these hiker/skiers reached Roaring Springs, lugging those skis to the river and up the South Kaibab Trail did not seem nearly as appealing as it had in the planning stages, and many skis/poles were abandoned along the trail. Bruce gathered up so many of these and stuck them in his shed, that he was said to be as well-equipped as any outfitter in Flagstaff, Phoenix, or Tucson.”

Up out of the Canyon

About 1988 as the children were getting older. It was harder to keep them in the canyon with all the activities that they wished to be involved in. Tension increased with the Grand Canyon School District about homeschooling and the Aikens decided that their older girls needed to attend the public school. They purchased a home at the South Rim and Mary moved up with the kids when school began in the fall. Bruce visited often and joined then in mid-October. When school was closed for the summer, they all returned to Roaring Springs.

In 1991, Bruce was earning $28.000 annually, including taking four months off. Sales of his paintings doubled his salary. He started private art instruction and teaching classes at the community college in Flagstaff. About his art, it was said, “Bruce’s big claim to fame is the fact that he lives in the Grand Canyon. The canyon belongs to him and no one can touch it quite like him. There are other people that paint the canyon, but Bruce lives it.”

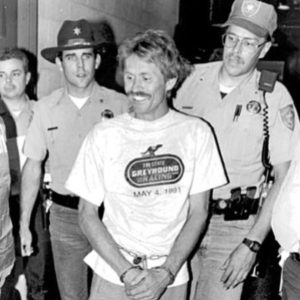

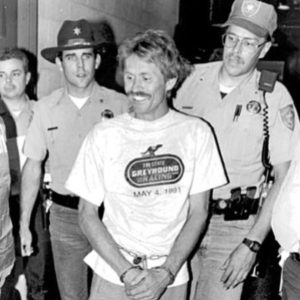

Search for Danny Ray Horning

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S1ZNkA7GCfI search video

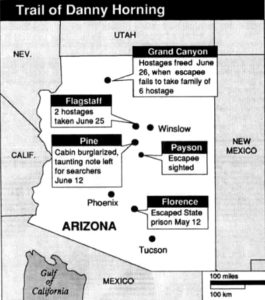

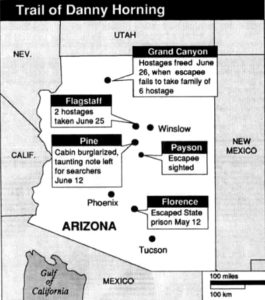

Horning made his way up to

Bruce commented, “From a purely outdoorsman standard, the fact that the man managed to elude so many trained people for so long is simply amazing. I don’t like what I’ve heard about him. But you’ve got to give him credit on that score.”

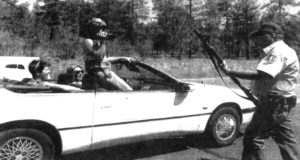

Days later, after carjacking on the South Rim and taking hostages, Horning headed south and was eventually captured at Oak Creek Village, near Sedona, Arizona. He had been on the run for seven weeks. He was returned to prison and his four life sentences and later was convicted of murder. In 2020 he was on death row at San Quentin Prison.

Children leaving home

As the children were flying out of the Roaring Springs coop, Mary was asked about their plans for future years, she said, “As soon as the children are settled as gone, I suppose it will be me and Bruce, sitting on the front porch, watching our hair grow long and grow white.”

In 1994, at the age of 21, Mercy Aiken, was working as a ranger on the North Rim. She was interviewed about her life growing up in the Grand Canyon. “I’ll live in other places, but the Grand Canyon is the only home I’ll ever have. The Canyon was the center of my everyday life, not just a place to visit and take pictures. It’s my wish that people can have life-touching experiences here for a long time.” Mercy was majoring in English at Northern Arizona University at Flagstaff, Arizona between stints as a ranger. She thought about writing a book about growing up in the Canyon. That year Mary worked at the Grand Canyon Airport on the South Rim and commuted at times on foot to Roaring Springs.

In 1996, Silas attended high school on the South Rim and was involved in sports. Two-thirds of the students’ parents were employed by the Park. Silas, 18, said, “The town is definitely boring for the city kids who move here, but as far as the canyon goes, it’s the best part of my life. Quite a few kids get into the canyon, but a lot of them are just like, whatever. They can’t see it or understand it.” Silas graduated from high school and the Aikens became empty-nesters. He went to college in Flagstaff and Mary moved back to Roaring Springs.

The final years at Roaring Springs

Life after the Canyon

After being away for several years, Bruce and Silas hiked back down to Roaring Springs and found the place that they had lived was sadly unmaintained. The lawn was no longer green and lush and the house was getting run down. Silas said, “It occurred to me that someone needed to be there full-time, and that someone needed to be me.” He wrote the Park superintendent and volunteered for the job and Silas returned to his childhood home as a “Volunteer in the Park.” He said, “I have such a great memory of the place. And the things I missed the most and the things I wanted to see the most were the extra blue of the sky against the red rock. It delivered better than I remembered. I slept outside in the breeze and by the sound of the creek.” He would later be hired as a ranger and continue to help hikers at his former home.

In 2016, Bruce ran his gallery in downtown Flagstaff and taught art full-time at Northern Arizona University. Of the canyon he got emotional and said, “I miss it terribly.” He was planning a trip to Nepal, near Mount Everest. Mary was retired.

Mercy was a Christian missionary at Bethlehem Bible College in Israel. She remembered, “We would read the Bible together, so our faith was there more on a daily basis. Because we were so remote, we could not be part of a regular church. I think it helped me. Religion was more organic and real and part of our everyday life. God has spoken to me a lot through the Canyon.”

Shirley also became an artist, had two children and owned a spa-treatment business in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Silas was married with two children, living in Flagstaff, and still working part-time as a ranger in the Canyon. He said in an interview, “I was so lucky to grow up where I did. You can’t have an upbringing like I did and not be a spiritual person. It gave me an appreciation of nature and an appreciation of God. It’s like the Grand Canyon was like a finger of God.”

Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim Series

- 46: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 1 (1890-1928)

- 47: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 2 (1928-1964)

- 48: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 3 (1964-1972)

- 49: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 4: Aiken Family

- 50: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 5: The Races

- 135: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 6: Early Guides

- 136: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 7: Prof Cureton

- 137: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 8: Kolb Brothers

- 138: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 9: Phantom Ranch

Sources:

-

- Arizona Daily Sun (Flagstaff, Arizona), Jan 19, May 17, 1948, Jun 4, Sep, 1978, Aug 25, 1982, Jul 28, 1991, Apr, 25, 1996, Mar 7, 2003

- Tucson Citizen (Arizona), Jun 9, 1978

- Arizona Republic, Oct 3, Dec 9, 1978, Jul 26, 1981, May 3, Jun 28, Jul 1, 6, 1992, Oct 1, 2000, Apr 10, 2016

- South Florida Sun Sentinel (Fort Lauderdale, Florida), Mar 13, 1997

- Washington County News (Saint George, Utah), Jun 13, 1974

- Arizona Daily Star (Tucson, Arizona), Jul 26, 29 1994, Jul 2, 1999

- Sun Sentinel (Florida), Aug 11, 1985

- Washington Post, June 23, 1999

- Susan Hallsten McGarry, Bruce Aiken’s Grand Canyon: An Intimate Affair

- Seth Muller, Canyon Crossing: Experiencing Grand Canyon Rim to Rim

- Bruce Aiken Facebook Page

- Bruce Aiken Instagram Page

- Michael P Ghiglieri and Thomas M Myers, Over the Edge: Death in Grand Canyon

- Woody Harrell email correspondence, 2020