Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 34:15 — 42.5MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

Part 5 of the Rim-to-Rim History Series. See also Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, and Part 4

Believe it or not, races across the Grand Canyon used to be conducted for hikers and runners. Early on, they occurred with the approval of the National Park, but in later years they were held contrary to rules set forth by the park. Eventually underground races or large commercial rim-to-rim hikes became a point of controversy and outsiders commented that rim-to-rim hikers and runners were turning the Grand Canyon into their own private sports arena for a day.

Believe it or not, races across the Grand Canyon used to be conducted for hikers and runners. Early on, they occurred with the approval of the National Park, but in later years they were held contrary to rules set forth by the park. Eventually underground races or large commercial rim-to-rim hikes became a point of controversy and outsiders commented that rim-to-rim hikers and runners were turning the Grand Canyon into their own private sports arena for a day.

But within all these various events appeared some incredible athletic accomplishments and unforgettable experiences. There are many ways to enjoy the Canyon whether fast or slow, in a day or within a week. There were some key individuals who helped others open their minds to understand what adventures were possible that decades earlier were thought to be impossible. Most were careful to respect the Canyon and the others enjoying it, but others were not.

Jerry Jobski

Jerry Jobski, born in 1944, never ran track in high school, was co-captain of his basketball team, but sat on the bench. He went into military service during the Vietnam War, and when he returned, he thought he might try baseball at Arizona State University at Tempe. But when he saw a notice seeking cross-country runners, he applied. The coach asked him about his running history, and he said he had none.

Jobski said, “I had no idea what cross-country runners wore, so I went down and bought me a pair of track shoes.” When he showed up with those shoes, one team member laughed, “Man, you don’t need those where we’re going to run in the desert.” Jobski quickly became one of the team’s premier distance runners. He broke the university’s 3-mile record in 1969 with 13:30. He and teammate Chuck LaBenz would run 150-mile weeks at times. LaBenz had broken a four-minute mile with 3:58.4

1970 Race, North to South

In October 1970, perhaps the earliest race across the Canyon was held. It was a three-man race, north to south. The participants were former Arizona State University (ASU) elite distance runners, Jerry Jobski, Chuck LaBenz, and George Young. Their goal was to break the three-hour barrier. The current fastest-known time was 3:56 set in 1963 by Allyn Cureton of Williams Arizona.

In October 1970, perhaps the earliest race across the Canyon was held. It was a three-man race, north to south. The participants were former Arizona State University (ASU) elite distance runners, Jerry Jobski, Chuck LaBenz, and George Young. Their goal was to break the three-hour barrier. The current fastest-known time was 3:56 set in 1963 by Allyn Cureton of Williams Arizona.

About the Grand Canyon race, Jobski said, “It was George’s idea and Chuck thought it was great. I said they were both nuts. The night before the run, I had no intention of participating. But “Baldy” (Senon “Baldy” Castillo (1919-2009), ASU track coach) called me up and I said I’d go, on the spur of the moment.” Jobski won the rim-to-rim race with a time of 3:08, lowering the fastest known time. For his win, he received a Coke and a hand-made ribbon from Young’s wife.

About the Grand Canyon race, Jobski said, “It was George’s idea and Chuck thought it was great. I said they were both nuts. The night before the run, I had no intention of participating. But “Baldy” (Senon “Baldy” Castillo (1919-2009), ASU track coach) called me up and I said I’d go, on the spur of the moment.” Jobski won the rim-to-rim race with a time of 3:08, lowering the fastest known time. For his win, he received a Coke and a hand-made ribbon from Young’s wife.

A few months later, in 1971 Jobski ran his first marathon winning the Admission’s Day Marathon with 2:36:42, breaking that marathon’s record by 14 minutes. Jobski said, “I didn’t know you were supposed to take sustenance during the race, so I ran all the way without a drink.” In 2020, Jobski was 75 years old and living in Page, Arizona. For a time in the early 70s, LaBenz was America’s greatest miler, known for a blazing kick, beating famed runners such as Dave Wottle, Marty Liquori, and others. In 2020 LaBenz was 71 and living in Scottsdale, Arizona.

Bill Emerton’s Double Crossing attempt

In 1974 Bill Emmerton (1920-2010), a self-promoting ultrarunner legend from Australia, living in Ohio, went to the Canyon to run a double crossing. Previously Emmerton had run 800 kilometers from Melbourne to Adelaide in 1965. He also ran two long-distance runs through Death Valley is soaring temperatures in the 1960s.

In 1974 Bill Emmerton (1920-2010), a self-promoting ultrarunner legend from Australia, living in Ohio, went to the Canyon to run a double crossing. Previously Emmerton had run 800 kilometers from Melbourne to Adelaide in 1965. He also ran two long-distance runs through Death Valley is soaring temperatures in the 1960s.

For his Grand Canyon run, Emmerton, at age 53, spent a day of training at Flagstaff’s Northern Arizona University to prepare for his run. He received significant newspaper attention for his rather foolish hot August attempt. At his Yaki Point start at 6:00 a.m., he was cheered on by Grand Canyon Park superintendent, Merle Stitt, and many other rangers as he descended South Kaibab Trail. He planned on a 14-hour R2R2R.

Emmerton had a rough time with the trails, only made two five-minute stops, but finished his first crossing in a slow 7:45. He was greeted by many tourists and park personnel. Despite all the news coverage, he decided to quit. He said, “This was the most difficult run I have made during my entire life.”

Emmerton had a rough time with the trails, only made two five-minute stops, but finished his first crossing in a slow 7:45. He was greeted by many tourists and park personnel. Despite all the news coverage, he decided to quit. He said, “This was the most difficult run I have made during my entire life.”

He justified his decision to quit at one crossing with, “The trails were too narrow and would have been impossible for me.” He said that the North Kaibab trail was filled with loose sand and rocks, making it hard for him to get good traction. “The rocks also caused several bruises on both feet, which was one factor which helped in making the decision against the return run.”

Rangers thought his single crossing run was a record, but it wasn’t even close to Jerry Jobski’s 1970 fastest known time of 3:08. The rangers gushed over his effort. One said, “You have just set an endurance run which may never be broken, especially by someone your age.” Emmerton commented, “Man, some of the scenery was breathtaking and some of it was also scary, especially in spots where the trail was narrow and some of the straight drops were around 1,000 feet.” His run was written up in Sports Illustrated. He ran again the next year and completed a single crossing in 4:52.

1974 North to South Race

In October 1974 Jerry Jobski and Chuck LaBenz again raced across the Canyon north to south. Jobski said, “They made a God of Evel Knievel for trying to jump the Snake River Canyon. I told Chuck I’d like to see Evel follow us through the Canyon. We’d even let him bring his motorcycle along.” Jobski won again and slightly lowered his own fastest-known-time for a single crossing. He finished in 3:07:27 and LaBenz finished in 3:15:44.

Max Telford’s 1976 Double Crossing

In 1976, Max Telford went to run a Grand Canyon double crossing (R2R2R). Telford was from Scotland, New Zealand, and later Hawaii and the Philippines. He was known mostly for being a solo journey ultrarunner. He sought out running adventures to be the first or the fastest, to get his name in the Guinness Book of World Records. He never really competed against the best in the world and did a lot of self-promoting, working with sponsors. But he greatly inspired others to run and had legitimate elite ultrarunner ability. He had ambitions “to become the greatest long distance runner of all time” and people at his time believed that he was, based on his self-promotion.

In 1976, Max Telford went to run a Grand Canyon double crossing (R2R2R). Telford was from Scotland, New Zealand, and later Hawaii and the Philippines. He was known mostly for being a solo journey ultrarunner. He sought out running adventures to be the first or the fastest, to get his name in the Guinness Book of World Records. He never really competed against the best in the world and did a lot of self-promoting, working with sponsors. But he greatly inspired others to run and had legitimate elite ultrarunner ability. He had ambitions “to become the greatest long distance runner of all time” and people at his time believed that he was, based on his self-promotion.

In 1976, Telford ran across Death Valley in January, breaking what was said to be a fastest known time by 15 hours in 90 degree heat. But he was told by Californians that he did it wrong, that it needed to be done in the summer. So Telford planned to do it right, and this time run a double Death Valley run. He trained by running on a treadmill in a sauna, in Auckland, New Zealand

Telford came to the US two weeks prior, and used a double Grand Canyon crossing as a tune-up run for his Death Valley run. He said of the Canyon, “When I first saw it, I was overwhelmed. The switchback trail was only 3-6 feet wide, very stony, very dangerous.”

Telford came to the US two weeks prior, and used a double Grand Canyon crossing as a tune-up run for his Death Valley run. He said of the Canyon, “When I first saw it, I was overwhelmed. The switchback trail was only 3-6 feet wide, very stony, very dangerous.”

The park rangers were thrilled and told him that a double crossing had never been done before. (But of course it had, see Part 2). As Telford was coming back up out of the canyon, the rangers told the tourists what was happening, and several hundred people cheered when he finished in 8:34. It was the fastest known time.

In July he succeeded in running across Death Valley and back (Shoshone to Scotty’s Castle), a distance of 240 miles in 73 hours. The temperature got up to about 125 degrees in the shade. When he finished, he wept, something his wife had never seen him do before after a running effort. He explained that he had never been to hell and back before. Of the adventure, he said, “I drank 10 gallons of water without once relieving myself and still lost 10 pounds. It took me six weeks to recover.” Telford soon claimed that he was the greatest ultrarunner in the world. He wasn’t, but his stunts received a lot of publicity.

Ken Young

Ken Young was geophysicist at the Institute of Atmospheric Physics in Tucson, Arizona and was referred to as the “guru of running” in Tucson. In 1971 Young began a daily running streak of at least one mile a day that lasted nearly 42 years. In 1972 he set the marathon world indoor record in Chicago of 2:41:29. Later that year ran 100 miles in 14:14:39 at Camelia Festival at Sacramento, California.

Ken Young was geophysicist at the Institute of Atmospheric Physics in Tucson, Arizona and was referred to as the “guru of running” in Tucson. In 1971 Young began a daily running streak of at least one mile a day that lasted nearly 42 years. In 1972 he set the marathon world indoor record in Chicago of 2:41:29. Later that year ran 100 miles in 14:14:39 at Camelia Festival at Sacramento, California.

Starting in 1975, Young started running on various trails around Tucson. In 1976, he and a training partner set themselves a goal to run up and down the four highest peaks around Tucson, including 9,156-foot tall, Mount Lemmon. They had a rough go of it with overgrown brush and a blizzard, but they survived. Ken then had the idea to establish organized races on the trails. Various small races were put together starting in 1977. Young won many of them.

During May 1977, Young, age 35, ran across the Grand Canyon south to north in 3:45. He said, “It wasn’t pleasant. The only thing pleasant about it is finishing so you can lie down.” He had his sights on running a double crossing in less than seven hours. Young started an annual newsletter called “Arizona Mountain Runner” and soon expanded his trail races to the Grand Canyon.

Woody Harrell

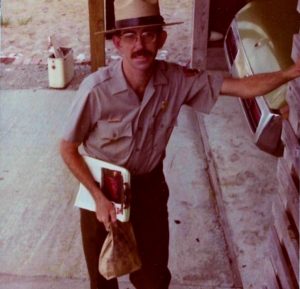

In 1977, Haywood “Woody” Harrell was a new NPS ranger. When he attended eight weeks of training, he was told there was a concern about out-of-shape park rangers, some who had died on the job from heart attacks. Physical fitness was encouraged. Harrell was an elite marathon runner who had finished Boston in 2:36:27 in 1975. When the NPS discovered that their rookie ranger had this ability, they thought it would be inspiring if one of their own tried to run rim-to-rim and beat Max Telford’s known single-crossing North to South time.

In 1977, Haywood “Woody” Harrell was a new NPS ranger. When he attended eight weeks of training, he was told there was a concern about out-of-shape park rangers, some who had died on the job from heart attacks. Physical fitness was encouraged. Harrell was an elite marathon runner who had finished Boston in 2:36:27 in 1975. When the NPS discovered that their rookie ranger had this ability, they thought it would be inspiring if one of their own tried to run rim-to-rim and beat Max Telford’s known single-crossing North to South time.

Harrell wrote, “They arranged a helicopter ride across the canyon for me which involved going down to pick up a plumber and his tools, who had been winterizing some pipes at Roaring Springs; and on the day before Thanksgiving (November 23, 1977) I ran back to the south rim in 3:23:34 just missing breaking Telford’s time of the previous year.

1978 North Kaibab Slide

The winter and spring runoff in 1978 caused significant damage to the North Kaibab Trail above Roaring Spring and that section was closed when the North Rim opened for the season. “Blasting is necessary in several places where the trail has just disappeared, but most work is done by hand and use of mules. This is because power equipment cannot be driven or transported to the damaged section.” $168,000 of emergency funds was proved to rebuild the trail.

Twenty-eight temporary employees were hired, including six women to repair and improve the North Kaibab Trail. “Since February, working 10-day shifts, followed by four days off, they had cleared, widened and leveled nearly seven miles of trail from the Colorado River north to Roaring Springs campground.” In June they started on the hardest hit area, a large slide area about a half mile below Supai Tunnel.

“Each day they commuted from a house on the North Rim to the work site. Everyone was out of the house by 7 a.m. on their way down the trail through the pristine morning air. By 8:30, the foremen with the pack mules arrived at the slide area from the top, and the slow difficult task of blasting, clearing and scraping out a path began” They used a gasoline driven jack hammer in addition to picks and shovels. In the hot summer their workday ended at 2 p.m.

Karen Loftin, of Northern California, was one of the trail workers. She said, “I’ve never had biceps in my life, now I do and I feel healthier than I ever have.” She had been fired from a job putting up siding on homes and came to the Grand Canyon for work. She said, “The first five or six days I came home exhausted and went to bed at 7 p.m.” But she quickly got into trail working shape has would often go for a bike ride on the North Rim after work.

1979 Houston group double crossing attempt

In 1979 a group of five runners from Houston planned to run across the Canyon south to north and then back the next day. All went well until about mile 22 on the North Kaibab trail. The winter/spring runoff had again ravaged a half mile section of North Kaibab Trail in Roaring Springs Canyon. The trail dropped away down a cliff. They considered running back but doing 44 miles was outside their abilities. They eventually scrambled around the damaged section and made it to the North Rim after a 9.5-hour run. The North Rim rangers were not pleased, said they could have cited them, and wouldn’t let them go back down the next day. The runners took a $298 10-minute helicopter ride back.

1978 and 1979 North to South Rim Races

In 1978, Ken Young organized the first open race across the Canyon with a small group, north to south. The next year, in September 1979, the race grew to twenty-four runners, including one woman. All of them finished with Mike Foster, 37, of Phoenix, the overall winner in 3:06:59. Kathy Shipp of Tempe, Arizona finished in 7:10.

In 1978, Ken Young organized the first open race across the Canyon with a small group, north to south. The next year, in September 1979, the race grew to twenty-four runners, including one woman. All of them finished with Mike Foster, 37, of Phoenix, the overall winner in 3:06:59. Kathy Shipp of Tempe, Arizona finished in 7:10.

Wally Shiel, age 26, who finished 5th in 3:52:50 explained, “We started at 5:30 in the morning. The sun hadn’t even come out yet. We were running by moonlight. We started at the north rim on the Kaibab Trail. It was very cold in the beginning, about 40 degrees at the start. By the time the sun came out we were out of the pines and in the desert vegetation.” He commented that it was very different than running on the pavement. “There were logs, holes, rocks and even people in sleeping bags we had to jump over.”

Wally Shiel, age 26, who finished 5th in 3:52:50 explained, “We started at 5:30 in the morning. The sun hadn’t even come out yet. We were running by moonlight. We started at the north rim on the Kaibab Trail. It was very cold in the beginning, about 40 degrees at the start. By the time the sun came out we were out of the pines and in the desert vegetation.” He commented that it was very different than running on the pavement. “There were logs, holes, rocks and even people in sleeping bags we had to jump over.”

After crossing the Black Bridge, they headed up the South Kaibab Trail. “We carried water in bottles and on our belts, but dehydration was just a matter of time. Hikers coming down would give us water. We were running out. There was another race we were involved with at that point, getting out of the sun. Our incentive was to get out of that heat.”

After finishing, Young asked Shiel, “Wally, what do you think of running across the canyon and back?” He replied, “Ken, I don’t know. We’ve just been running for four hours and I’ll have to think about it later.” These thoughts would lead to a double crossing race.

1980 Flash Flood

On September 9, 1980 a flash flood occurred affecting the trail. A rain and hailstorm deposited more than one inch of precipitation in less than 20 minutes and then it kept raining the rest of the day. There was substantial damage. Numerous sections of both the Bright Angel and North Kaibab trails were completely obliterated.

Park Superintendent, Richard Marks said, “The campground and water system at Indian Garden on the Bright Angel trail were washed out. Fortunately, the trans-canyon water pipeline remained intact as far as we can tell.” Bright Angel and North Kaibab trails were immediately closed but South Kaibab trail remained open. All inner canyon hikers were asked to check in with the backcountry office for updates.

Allyn Cureton

Allyn Carl Cureton (1937-2019) was from Williams, Arizona. When he was 15 years old, in 1952, he accomplished his first rim-to-rim hike with his father. He went on to attend Arizona State College (now NAU) in Flagstaff, Arizona, where he ran track. He became an active member of the college’s hiking club and president starting in 1957. He was also known for his long-distance bicycling and very long hikes down in the Grand Canyon. He hiked on many adventures with Grand Canyon explorer Harvey Buchart. By 1962 Cureton had made 48 trips into the canyon including a long 90-mile hike length-wise. Cureton became an early elite trail runner in Arizona and would set the standard for rim-to-rim runs.

Allyn Carl Cureton (1937-2019) was from Williams, Arizona. When he was 15 years old, in 1952, he accomplished his first rim-to-rim hike with his father. He went on to attend Arizona State College (now NAU) in Flagstaff, Arizona, where he ran track. He became an active member of the college’s hiking club and president starting in 1957. He was also known for his long-distance bicycling and very long hikes down in the Grand Canyon. He hiked on many adventures with Grand Canyon explorer Harvey Buchart. By 1962 Cureton had made 48 trips into the canyon including a long 90-mile hike length-wise. Cureton became an early elite trail runner in Arizona and would set the standard for rim-to-rim runs.

In May 1962, Cureton attempted to beat the fastest known time across the canyon. He accomplished it in 4:15. His time bested the time held by Park service employee Willie Stienkraus for 4:45. In November 1963, Cureton again lowered the mark with a time of 3:56. It was written in the newspaper, “With apt promotion, the run through the mile-deep chasm could become a unique sporting competition.”

In May 1962, Cureton attempted to beat the fastest known time across the canyon. He accomplished it in 4:15. His time bested the time held by Park service employee Willie Stienkraus for 4:45. In November 1963, Cureton again lowered the mark with a time of 3:56. It was written in the newspaper, “With apt promotion, the run through the mile-deep chasm could become a unique sporting competition.”

One friend commented, “Allyn was one of a kind, a very unique person to say the least. Quirky, a bit of a loner, and a very kind-hearted person. Running and fitness was his niche he carved out of life.”

1980 and 1981 Rim to Rim races

On October 5, 1980, a North to South race was held with 16 finishers. Jennifer Hesketh recalled that it was her first single crossing of the Canyon. She shared a cabin with several men and before the race helped braid Fred Riemer’s long hair before heading out.

On October 5, 1980, a North to South race was held with 16 finishers. Jennifer Hesketh recalled that it was her first single crossing of the Canyon. She shared a cabin with several men and before the race helped braid Fred Riemer’s long hair before heading out.

Later, in November 1980, Young, Hesketh, and Kathy Shipp traveled back to the Grand Canyon to run double crossing as a test case starting at the South Rim. Hesketh wrote, “Kathy and I started at 3 a.m. in the light of a beautiful full moon. I needed to turn around at Cottonwood Campground and hiked back out due to ITB troubles. Ken finished in 9:22 and Kathy in 15:41. Ross Zimmerman and his family including his wife Emily and baby son Gabe came up with us. Ross hiked out with Kathy that cold evening,”

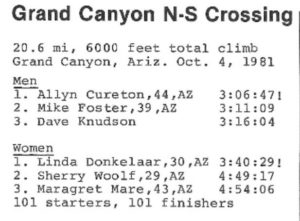

The race grew exploded the next year and on October 4, 1981, had 101 starters. It was north to south that year and all finished. Two groups started ahead of the main group. Jennifer Hesketh reported, “In the early morning semi-darkness, the runners streamed down the rocky, muddy and washed-out trail. The climb out at the south end was muddy and slippery too. Some people from the South Rim supplied the heretofore unheard of, but wonderfully appreciated four aid stations, with water.” Allyn Cureton, 44, finished in 3:06:47 lowering the fastest known time, and Linda Donkelaar finished in 3:40:29.

1981 Double Crossing Race

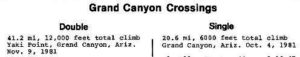

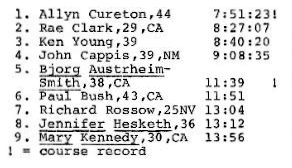

On November 9, 1981, Young and Hesketh organized the first Grand Canyon Double Crossing race (R2R2R) starting at the South Kaibab trailhead. At Western States 100 that year Young and Hesketh invited some California runners to join in. Nine brave runners participated with five taking an early start at 3:46 a.m. The others started at 6:30 a.m.

On November 9, 1981, Young and Hesketh organized the first Grand Canyon Double Crossing race (R2R2R) starting at the South Kaibab trailhead. At Western States 100 that year Young and Hesketh invited some California runners to join in. Nine brave runners participated with five taking an early start at 3:46 a.m. The others started at 6:30 a.m.

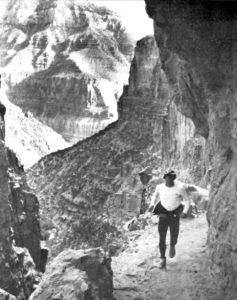

The upper North Kaibab trail was pretty washed out in places. Hesketh reported, “The race really began on the return leg, with most people letting out the stops, and returning at a brisk pace.” One observer stated, “On some areas of the Kaibab Trail, one wrong stride and the runner won’t have to worry about permanent injuries, the rest of the season, or the rest of his life for that matter.”

Picking up speed going down Bright Angel Canyon Hesketh wrote, “Everyone slowed for what is affectionately known as ‘Asshole Hill,’ which is where the trail for some unexplained reason leaves the creek and climbs up over a small hill right where it shouldn’t.” (It leaves the canyon floor because of an unstable steep slope near the creek.) John Cappis took a brief nap at Phantom Ranch before the last big climb.

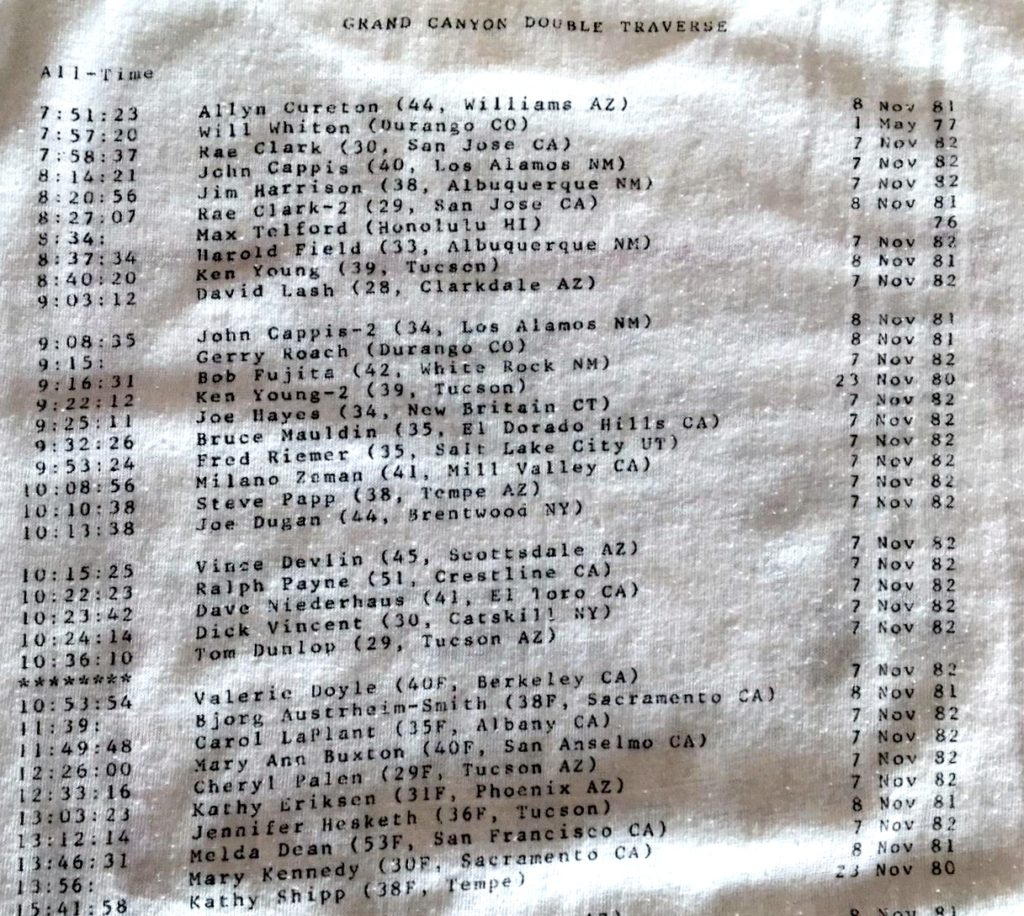

Allyn Cureton won in 7:51:23 which was the fastest known time for a double crossing. He rode his bicycle 60 miles to and from the race. Cureton set the bar for future runners. It was at least 25 years before his records were broken. Bjorg Austrheim-Smith set the women’s fastest known time with 11:39.

Allyn Cureton won in 7:51:23 which was the fastest known time for a double crossing. He rode his bicycle 60 miles to and from the race. Cureton set the bar for future runners. It was at least 25 years before his records were broken. Bjorg Austrheim-Smith set the women’s fastest known time with 11:39.

The first Double Crossing race was a great success. Hesketh commented, “The event is tiring and the final climb is at the wrong place, but you can’t argue with the fact that you don’t finish, or go home with that matter, unless you climb out. But we all agreed that it was an experience not to be missed.”

1982 North to South Race

In October 1982, the “Grand Canyon Single Crossing” race was again held, north to south with 116 starters and finishers. Rob Turan, who worked for the Fred Harvey Company at the Grand Canyon recalled that the Arizona Road Racers contacted him as Recreation Coordinator to help organize the race. “I got volunteers to help carry five-gallon buckets of water and set up aid stations on South Kaibab so the runners didn’t have to carry water. A huge finish sign was erected with a time clock. It was a major event.” Allyn Cureton won again in 3:16 followed by two back-country rangers. Mark Sinclair and Bob Guthrie. Rebecca Felton, a skier and triathlete from Salt Lake City, Utah won among the women with 4:53:54. There were complaints from hikers that this group had poor trail etiquette and there were reports that they were disruptive to others in the restaurants and other facilities on the rim.

1982 Double Crossing Race

On November 7, 1982, the Grand Canyon Double Crossing race exploded to 50 runners and again started at the South Rim. Runners came from all over the country and there was no entrant’s fee. A sponsorship from Nike was obtained and shirts were produced, designed by Greg Franklin. Approvals for the race were obtained from the Park Service. Runners needed to bring their own aid.

On November 7, 1982, the Grand Canyon Double Crossing race exploded to 50 runners and again started at the South Rim. Runners came from all over the country and there was no entrant’s fee. A sponsorship from Nike was obtained and shirts were produced, designed by Greg Franklin. Approvals for the race were obtained from the Park Service. Runners needed to bring their own aid.

Runners were warned, “The cost to haul you out should you be injured or just plain tired out could run between $75-100. You are on your own once you begin. The trail is not maintained on the North Rim part. It will be leaf strewn, washed out, rocky, and in some parts very dangerous. One section, the cliffs, is blasted out of rock and has a very sheer drop off. The last climb out can be exhausting. You must climb out if you want to go home. There are no aid stations, course monitors, trophies, or anyone to hold your hand.”

A large room was provided by the Park at a lodge for a race briefing. The runners could choose between four start times from 2:35 a.m. to 6:39 a.m. The groups became congested near the turnaround at the North Rim. Rae Clark won with 7:58, with John Cappis second, finishing in 8:14. Valerie Doyle set the women’s fastest known double-crossing time with 10:53. All but one of the starters finished the complete double.

One runner said, “Imagine a 4 a.m. start, 6 ½ miles down a winding trail with a 4,800-foot drop in the dark. The only good things were, you could not see how really dangerous and steep the trail was and you could not gauge how incredible the return would be.” The weather that year was perfect.

After that year, a major television network was interested in televising a rim-to-rim run with 1,000 runners. That got the Park’s attention. The Grand Canyon National Park Service requested that no “formal, organized competitive events or spectator sports” take place within the park. Young and Hesketh complied and stopped organizing a double cross race.

1985 Double Crossing Race

But only three years later, on November 3, 1985, a “Grand Canyon Double Crossing” was organized by Fred Riemer, 37, from Utah. That year 23 runners started and 21 runners finished. They used three different starting times from 3:15 a.m. to 6:15 a.m. with near-freezing temperatures on the South Rim. The inner canyon reached a comfortable 76 degrees. All runners carried a little food and a water bottle. Most runners stopped at Phantom Ranch for a rest and lemonade. Riemer set up two aid stations on the final climb. Rae Clark won with 9:04. Cindy Suplizio, a well-known triathlete from Salt Lake City, Utah, lowered the women’s fastest known time of 10:28. She placed fifth overall.

Sid Hirsh

Sid Hirsh, born in 1930, grew up in Tucson, Arizona where his mother opened a children’s shoe store in 1954. Hirsh worked there after serving in the Korean War and eventually took over the family business that expanded into a chain for stores in Tucson. He said that he used to be a chain smoker in his younger years, but he always enjoyed walking.

Sid Hirsh, born in 1930, grew up in Tucson, Arizona where his mother opened a children’s shoe store in 1954. Hirsh worked there after serving in the Korean War and eventually took over the family business that expanded into a chain for stores in Tucson. He said that he used to be a chain smoker in his younger years, but he always enjoyed walking.

In the mid-19 60s he went to a Sierra Club outing and he joined the club and got very involved. He then started to lead backpack trips to the Grand Canyon and other places. He met a Tarahumara man in Mexico who introduced him to fast hiking. “He told us he was going down to the river, have lunch, talk with some friends and come back out that evening. It was about 35 miles. We started to wonder why we were taking four days to do what he did in one day.”

60s he went to a Sierra Club outing and he joined the club and got very involved. He then started to lead backpack trips to the Grand Canyon and other places. He met a Tarahumara man in Mexico who introduced him to fast hiking. “He told us he was going down to the river, have lunch, talk with some friends and come back out that evening. It was about 35 miles. We started to wonder why we were taking four days to do what he did in one day.”

Hirsh soon succeeded doing a double crossing of the Grand Canyon, was so enthused about it, and decided to resurrect a double-crossing race even though it wasn’t authorized in the park.

1986 Rim-to-Rim 50

The annual double-crossing races started in 1986 and were held in late May when it could be very hot and dangerous. That first year, thirteen started and ten finished. The race started with hikers but with each year more runners joined in. It began as a 42-miler using South Kaibab Trail.

1987 Rim-to-Rim 50

In 1987 the “Colorado Mountain Club” joined in the race. Twenty-six runners started along with a newspaper reporter who wrote, “We moved as fast as we could, trying not to become sudden cartwheels and spin-off into the river a mile below.” The winner finished in about 14 hours and four didn’t finish.

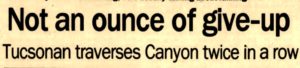

Wally Shiel

Wally Shiel, of Tucson, Arizona, was an Arizona ultrarunning pioneer in the 1980s and had run marathons since 1969. He took up ultras in 1980, winning a 100 km race on a 400-meter track in 9:36. He said, “Some 26-mile marathon runners think ultramarathoners are wacko, which is ironic because there are people who run the 10Ks who think the marathon runner is crazy.”

Wally Shiel, of Tucson, Arizona, was an Arizona ultrarunning pioneer in the 1980s and had run marathons since 1969. He took up ultras in 1980, winning a 100 km race on a 400-meter track in 9:36. He said, “Some 26-mile marathon runners think ultramarathoners are wacko, which is ironic because there are people who run the 10Ks who think the marathon runner is crazy.”

For Shiel, after a while the marathon just didn’t hold his interest anymore. “You get to a certain time and can’t go any faster, so you go to the ultramarathon or trail marathons.” He averaged training 70-90 miles per week. “In preparing for ultramarathons, I thought I would have to double my mileage during the week. I didn’t have to and that was a very pleasant surprise to me not to have to go 150 miles. In ultramarathon training, the emphasis is on time, on hours, rather than miles.” Shiel had a deep passion for running. He said, “Very few people I know unless they’re artists or workaholics have the kind of passion in their lives that I have for running.

Wally Shiel – 1987 Quad Crossing

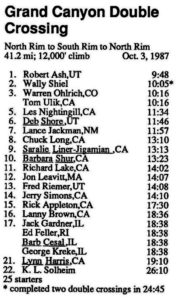

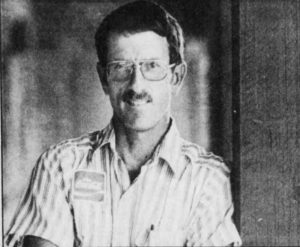

In 1987 Shiel was a Coca-Cola delivery man who had finished 96 marathons or ultras. He had conquered Western State 100 in 21:43. On October 3, 1987, a Utah version “Grand Canyon Double Crossing” was held with 25 starters, again organized by Fred Riemer of Utah. The race would start at the North Rim. Shiel entered the race but had far greater plans.

In 1987 Shiel was a Coca-Cola delivery man who had finished 96 marathons or ultras. He had conquered Western State 100 in 21:43. On October 3, 1987, a Utah version “Grand Canyon Double Crossing” was held with 25 starters, again organized by Fred Riemer of Utah. The race would start at the North Rim. Shiel entered the race but had far greater plans.

The night before the race, he camped with a group of runners on the North Rim trying to relax that evening before their Canyon run to start early in the morning. As the group was about to break up for the evening, Shiel said, “I guess we’re all going to have our own challenges tomorrow.” He told them he was going to do the same run they would do, only he would be doing it twice. There was a long silence. Then someone laughed nervously.

Shiel explained, “The single crossing was the pinnacle, and running once across one of the seven great natural wonders of the world was enough. The years passed and the double crossing began to take place regularly with increasing attendance. I never returned to the canyon. Then I read in our daily newspaper that local hikers walked back and forth across the canyon in a day. I was shocked and amazed. Surely only ultrarunners would attempt and could complete the double crossing. Instantly I was inspired to up the ante. I opted for a goal of four crossings of the Grand Canyon.”

Preparing for this daring run, Shiel watched “Rocky IV” twice in the days leading up to the challenge. “Rocky was getting beaten up by the Russian. Neither would give up, until finally the Russian gave way. I saw the Russian guy as the Grand Canyon.” He also used “Weight Watchers” to drop 20 pounds before the run.

The first runners started at 3:00 a.m. and the last runner went out just after 6:00 a.m. Shiel started at 4. “He snapped on his flashlight and threw himself into the blackness of the Grand Canyon’s North Kaibab Trail.” After his first crossing, Shiel’s dad, Walter, and this brother John greeted him at the South Kaibab trailhead, ready with food, water and dry clothes.

Shiel ran on and finished the first crossing in 10:05 good enough for second place in the formal race. The winner was Robert Ash of Utah in 9:48. Shiel’s wife Holly, crewed him on the North Rim. “Holly had set up a complete kitchen and aid station at the trailhead. Shiel grabbed a pot from a camp stove and began stuffing down warm spaghetti as he changed his socks. Clusters of people had been lounging around waiting for other canyon runners to return. They were puzzled by Shiel’s preparations. The word got out that he was going to run the canyon again.”

Shiel ran on and finished the first crossing in 10:05 good enough for second place in the formal race. The winner was Robert Ash of Utah in 9:48. Shiel’s wife Holly, crewed him on the North Rim. “Holly had set up a complete kitchen and aid station at the trailhead. Shiel grabbed a pot from a camp stove and began stuffing down warm spaghetti as he changed his socks. Clusters of people had been lounging around waiting for other canyon runners to return. They were puzzled by Shiel’s preparations. The word got out that he was going to run the canyon again.”

Onlookers wished him luck and within minutes he kept going to attempt the first quad crossing. Rick Kelley paced him 14 miles down to Phantom Ranch and waited there for his return for the last climb. Kelley had no doubt that Shiel would make it. He said, “Wally’s focusing power is incredible.” Kelley called up from Phantom Ranch reporting that Shiel was heading up to the South Rim.

About 3:30 a.m., Holy was waiting in a car near the North Kaibab trailhead. It was too cold to sit by the trail. She had set out a lantern as a beacon for the two runners to return. “Down below, a few miles from the top, the fire had almost gone out inside Shiel. The rock in the trail that he’d skipped over that morning he now had to stop for and step gingerly over. It hurt to run, and it hurt to rest.”

Shiel said, “It turned into a death march. Rick was taking care of me like a mother.” Kelley would rub Shiel’s back and legs each time he stopped. He tried hard to keep a good balance. “You’d turn the flashlight beam out there and it’d go off into oblivion.” Kelley said, “It turned into a basic survival thing. We were just trying to get our butts out of there.”

Finally above, Holly could see their lights heading toward the trailhead. “She jumped out of the car and rushed toward Shiel as he lurched into the lantern’s glow.” He accomplished the quad crossing in 24:45, the first ever to do that. He said, “I’m not masochistic. I don’t like pain. But it’s neat when the cards are stacked against you and you can keep going.” He knew that others would follow him doing the quad, and do it faster, be he knew that he was the first. “They can’t take that away.”

Finally above, Holly could see their lights heading toward the trailhead. “She jumped out of the car and rushed toward Shiel as he lurched into the lantern’s glow.” He accomplished the quad crossing in 24:45, the first ever to do that. He said, “I’m not masochistic. I don’t like pain. But it’s neat when the cards are stacked against you and you can keep going.” He knew that others would follow him doing the quad, and do it faster, be he knew that he was the first. “They can’t take that away.”

Jim Nelson (1961-2014) lowered the fastest known quad time in 1999 to 22:48, still held in 2020. I accomplished the quad in 2006, the fifth to do it, and added more miles to make it an even 100 miles. As of 2020, only about a dozen runners had accomplished a quad or more.

Continued Double Crossing Races

In 1989 44 runners started and 43 finished Hirsh’s rim-to-rim-to-rim race. That year it used the Bright Angel trail instead of South Kaibab Trail to get closer to 50 miles. Hirsh was asked why he kept putting on the race. He replied, “It’s my little baby. Hikers who never considered rim-to-rim-to-rim will decide to try it. They’ll run hard. And they’ll do it. It’s gotten competitive.” It is puzzling why a Sierra Club enthusiast would organize a “bandit” event in the National Park. He said, “I really believe what the Sierra Club stands for. We have to preserve the back country. We have to protect our quality of life.”

In 1992, again the upper North Kaibab Trail was destroyed by a slide between Supai Tunnel and the bridge across Roaring Springs Canyon. It took out nearly 9,000 feet of switchbacks. The slopes had been soaked by early winter rains, became very muddy, and then crashed down into the canyon. Bruce Aiken, at Roaring Springs, reported that it would take at least two months to rebuild. Rim to rim hikers were told that they could use the unmaintained Old Bright Angel Trail, taking the Ken Patrick Trail three miles from the North Kaibab trailhead and then descend down into Bright Angel Canyon along the original route. “A few hikers have been using this old trail each year, but there has not been enough traffic to keep it well defined. In some places it has disappeared. The trail disappears when you reach Bright Angel Creek.”

In May 1992, as Hirsh planned to put on the 7th Annual “Rim-to-Rim-to-Rim 50,” the Arizona Highways magazine featured a long story by William Hafford about the 1991 race in which the author described the start, “I am hemmed in by 63 bodies, male and female, bodies that shortly will propel themselves, taking me along, toward the edge of the abyss, then turn abruptly on the narrow trail at the Canyon’s edge, and lunge into the enveloping darkness.” The route that year went down Bright Angel Trail to Indian Garden, then on the primitive winding Tonto Trail to Tip off, down South Kaibab, up North Kaibab and back, for about 52 miles. If you finished in under 24 hours, you could buy a T-shirt. That year two runners bailed out at the North Rim and took a shuttle back.

Sandi Richmond hiked with her 15-year-old daughter and explained their DNF. “We were about a mile and a half from the North Rim. We stopped, talked it over, agreed it wouldn’t be smart to go on. We turned back, and when we reached Phantom Ranch, Rachel sat on a bench and cried. Then she said she was ready to climb back out of the Canyon.” It took them 22 hours, ten of it in darkness. The author of the story had fallen, sprained his ankle, and did not even make it to the river.

1992 Controversy

In 1992 a rockslide had again destroyed a portion of the North Kaibab trail, so Hirsch informed entrants the course would change to do an out and back on the Clear Creek Trail above Phantom Ranch. With the publicity of the Arizona Highways article, more than 100 people wanted to enter the race. Hirsh invited them in.

The Park Service was alarmed and not pleased with the article. Park Superintendent, Robert S. Chandler quickly wrote a letter to Hirsh saying that the race was unauthorized and required a special-use permit. The Park of course had no intention of approving such a permit, claiming it was dangerous to other hikers, mules, riders, and the participants.

The Park Service was alarmed and not pleased with the article. Park Superintendent, Robert S. Chandler quickly wrote a letter to Hirsh saying that the race was unauthorized and required a special-use permit. The Park of course had no intention of approving such a permit, claiming it was dangerous to other hikers, mules, riders, and the participants.

The formal 1992 race was “cancelled” and was unwisely changed to an informal gathering to run with Hirsh starting at 3:30 a.m. on May 16th. More than 80 runners showed up for the “informal” group. Two rangers waited at the trailhead. Hirsh read all the participants a statement that the Rim-to-Rim-to-Rim race was “no more,” but he was still going to run, and any others were welcome to join him, but they were on their own.

The rangers said that they had an illegal assembly and could all be cited. Angry exchanges took place but the runners were eventually allowed to go, once all of them gave their names and contact information. Participants were warned that they would need to pay for helicopter rides out.

The day in May was very hot and two hikers that day had to be rescued by helicopter and the Park continued to monitor the runners by air. Hirsh said, “The rangers meant well, but every time I passed one, I felt like a criminal.”

That was the last Hirsh Double Crossing event in the Grand Canyon, which The Arizona Daily Star of Tucson critically described as “the yearly opportunity to turn the Grand Canyon into their own private sports arena for 24 hours.”

Scott Beck’s organized rim-to-rim events

In the early 1990s, Scott Beck of Phoenix started to quietly organize rim-to-rim hikes/runs with friends, but each year the event grew. By 2011, it involved four tour buses full of people that left from Phoenix for a hotel in Kanab, Utah. The next morning the runners started in 30-minute waves at the North Rim and then the buses left to pick them up at the South Rim.

Hundreds of people were involved. Beck instructed participants that if asked who the organizer was, that they shouldn’t mention his name. Some would even wear blatant shirts that said, “Hello I’m Scott Beck.” But eventually someone needed to be rescued and word got out to the authorities. An article was published on nationalparkstraveler.org that explained that there were nearly 300 participants in 2014. It was the 23rd annual event. That day there were long lines at the Phantom Ranch canteen and the wastewater treatment operator reported that the sewage treatment plant was operating at capacity. It was reported that “several minor medicals and search and rescue operations were also attributed to Beck’s group.”

Hikers complained about trail congestion. Beck claimed the event was not commercial, but after a search warrant, it was discovered that the gross income was nearly $50,000 with a profit of $9,500. Beck was charged, convicted, received a plea agreement, was fined, and was banned from the Canyon.

Hikers complained about trail congestion. Beck claimed the event was not commercial, but after a search warrant, it was discovered that the gross income was nearly $50,000 with a profit of $9,500. Beck was charged, convicted, received a plea agreement, was fined, and was banned from the Canyon.

One hiker in the group later said that the park rangers were in foul moods because they had to come back to work after a government shutdown. “For the 22 years prior to this they never had a problem with it. It is really sad as to how the rangers acted that day.” But this person’s comments were blasted as being insulting to the park.

Also, about 2012, another large group was in the works originating from Utah. Plans were openly communicated on social media for multiple RVs to be rented and the event was to be conducted during the dangerous hot month of June. Anyone was invited and many first timers were excited to participate. Word got out, the Park discovered the plans and were prepared to shut it down. Apparently, it was cancelled. Other huge groups appeared, some couched as benefit runs. The National Park Service cracked down again on big group runs across the Canyon and started requiring permits.

Most Rim-to-Rim hikes

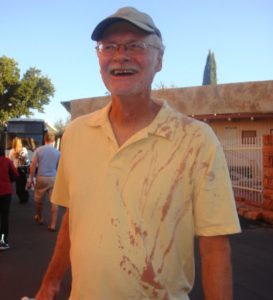

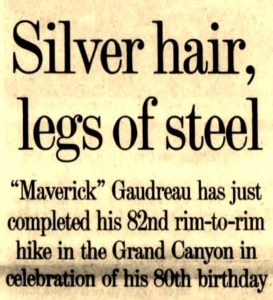

Laurent Osias Gaudreau (1926-2009) was originally from Massachusetts. He was stricken by polio as a child, later joined the Air Force as an X-ray technician and settled in the Philippines after World War II. He became a teacher, helped many children, but became an alcoholic. He moved to Denver, joined the military reserves, and moved to Moab Utah where he adopted the nickname of “Maverick.”

Laurent Osias Gaudreau (1926-2009) was originally from Massachusetts. He was stricken by polio as a child, later joined the Air Force as an X-ray technician and settled in the Philippines after World War II. He became a teacher, helped many children, but became an alcoholic. He moved to Denver, joined the military reserves, and moved to Moab Utah where he adopted the nickname of “Maverick.”

In 1998, at the age of 72, Gaudreau set a personal goal to hike rim to rim. He accomplished it the next year in 19 hours. Friends and co-workers were surprised and that encouraged him to obsessed with hiking rim to rim. “He thrived on people’s astonishment. With each additional R2R he completed, he and his public seemed to grow more inspired.” His best time was 10 hours 40 minutes.

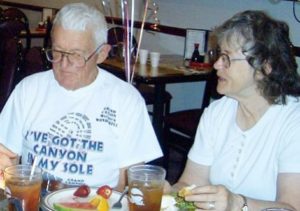

Gaudreau met Shirley (1936-2009) at the Grand Canyon and they married in 1999. They lived in employee housing and Shirley worked at bookstores. She said, “We have a wonderful life up here. We both love what we do and we have a nice place to live in. I always say, ‘I’m going to die here.” In 2004, Gaudreau quit his job and set his sights to complete 30 rim-to-rim hikes that year. He would carry a 15-pound pack with two liters of water and used a walking stick. He would usually allow three days for a round trip, camping at Cottonwood Campground.

Gaudreau met Shirley (1936-2009) at the Grand Canyon and they married in 1999. They lived in employee housing and Shirley worked at bookstores. She said, “We have a wonderful life up here. We both love what we do and we have a nice place to live in. I always say, ‘I’m going to die here.” In 2004, Gaudreau quit his job and set his sights to complete 30 rim-to-rim hikes that year. He would carry a 15-pound pack with two liters of water and used a walking stick. He would usually allow three days for a round trip, camping at Cottonwood Campground.

About Gaudreau’s hikes, Shirley said, “When he leaves, I always tell him, ‘Don’t forget to come home.’ It will never stop until he wants to stop.” He accomplished 42 crossings in 2004 and did 45 crossings in 2005. He said, “I’ve seen what a tremendous change it’s done in me. I talk to people on the trail, and the people say, ‘You’re an inspiration.’”

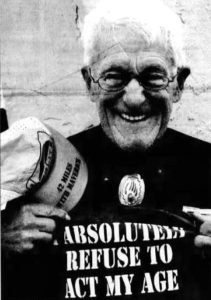

In 2006, 80-year-old Gaudreau wanted to accomplish 80 crossings that year, a record that he hoped would never be broken. He planned to hike every week of the year. By the end of the year, he completed an amazing 106 crossings. He said, “I absolutely refuse to act my age. I’m happier and healthier than I’ve been in my 80 years.” When asked why he didn’t stop at 80 crossings, he said, “My legs just kept going.”

In 2006, 80-year-old Gaudreau wanted to accomplish 80 crossings that year, a record that he hoped would never be broken. He planned to hike every week of the year. By the end of the year, he completed an amazing 106 crossings. He said, “I absolutely refuse to act my age. I’m happier and healthier than I’ve been in my 80 years.” When asked why he didn’t stop at 80 crossings, he said, “My legs just kept going.”

Gaudreau went on the self-promotion bandwagon, seeking media attention and adopted the name, “Rim-to-Rim Maverick.” His fame spread and he wrote a weekly column in the Grand Canyon News and on his blog. But in early 2009, he revealed that in his past he had terrible problems with anger.

Sadly, on February 5, 2009, Gaudreau made an early-morning 911 call, summoning rangers to his home at Grand Canyon Village, saying that he had just shot his wife. When they arrived, they discovered that he had indeed murdered his wife in her sleep and then took his own life. No motive was ever discovered.

Sadly, on February 5, 2009, Gaudreau made an early-morning 911 call, summoning rangers to his home at Grand Canyon Village, saying that he had just shot his wife. When they arrived, they discovered that he had indeed murdered his wife in her sleep and then took his own life. No motive was ever discovered.

Bruce Aiken, who lived in the Canyon (see part 4), knew Gaudreau well because of the frequent visits to Roaring Springs. Aiken mentioned that when Gaudreau started gaining fame, “something went really, really wrong with him. Whether it was an underlying, undiagnosed mental condition, I’m not sure. He was single-minded and hungry for attention. The more he got, the more he wanted. He never wanted to talk about anything other than himself, and he wasn’t into the Canyon. It was just about setting an unbeatable record of crossings. My wife Mary and I considered him harmless, but we both knew he was a kook.”

Those who knew the two in town said, “It’s been difficult as all of us try to cope with the shock and the realization that both of them are gone.” More than 150 people attended a memorial service for the two. Of Shirley it was said that she was known for her humor, her guidance to tourists and junior rangers. “She knew tremendous things about the Canyon and always shared a lot with visitors. When she worked at a deli, she knew your face and she knew what you were going to order.”

Those who knew the two in town said, “It’s been difficult as all of us try to cope with the shock and the realization that both of them are gone.” More than 150 people attended a memorial service for the two. Of Shirley it was said that she was known for her humor, her guidance to tourists and junior rangers. “She knew tremendous things about the Canyon and always shared a lot with visitors. When she worked at a deli, she knew your face and she knew what you were going to order.”

One writer put it this way, “Gaudreau’s iron man hiking and defiance of again inspired many people, especially seniors. On the flip side, whatever merits his example might have exemplified evaporated in a single moment of intense and inexcusable selfishness.”

Fastest Known Times and Crossing Records

As of 2020 the fastest known times for a double crossing is: 5:55:20 by Jim Walmsley set in 2016. Taylor Nowlin lowered the women’s best in 2018 to 7:25:58. For the single crossing, Tim Freriks lowered the time to 2:39:28 in 2017 and also that year Alicia Vargo ran in 3:19:23.

As of 2020 the fastest known times for a double crossing is: 5:55:20 by Jim Walmsley set in 2016. Taylor Nowlin lowered the women’s best in 2018 to 7:25:58. For the single crossing, Tim Freriks lowered the time to 2:39:28 in 2017 and also that year Alicia Vargo ran in 3:19:23.

Double Crossings Today

If you are planning to run a double crossing, don’t try to do it in the heat of the summer. The inner canyon exceeds 100 degrees and it isn’t fun to do when it is oppressively hot, and very dangerous. Summer in the inner canyon starts mid-May and lasts into September. A backcountry ranger who had worked at the Grand Canyon for two decades said, “Only fools and rangers hike the Grand Canyon in the summer. The rangers are only there to help the fools.”

Try April, October, or November. Please respect slower hikers, backpackers, and mule trains. Don’t stash anything along the way, especially at Phantom Ranch.

As of 2018, for rim-to-rim groups, a permit is required for groups of twelve or more and no commercial operations are allowed at all. All groups organized by non-profits require a permit. See: https://www.nps.gov/grca/learn/management/sup.htm

Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim Series

- 46: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 1 (1890-1928)

- 47: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 2 (1928-1964)

- 48: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 3 (1964-1972)

- 49: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 4: Aiken Family

- 50: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 5: The Races

- 135: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 6: Early Guides

- 136: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 7: Prof Cureton

- 137: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 8: Kolb Brothers

- 138: Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History – Part 9: Phantom Ranch

Sources:

- Arizona Republic (Phoenix, Arizona), Jun 21, 1962, Aug 9, 1965, Feb 22, 27, Apr 13, Dec 8, 17, 1966, Jan 20, Apr 19, May 28, 1967, Aug 5, 1969, Jul 25, 1970, Jun 19, 1973, Oct 26, 28, 1974

- Arizona Daily Sun (Flagstaff, Arizona), Nov 7, 1957, Nov 9, 1963, Dec 15, 1966, May 23, 1968, Nov 24, 1968, Jun 30, 1969, Dec 16, 1969, Aug 27, 1974, Sep 10, 1980, Oct 18, 2006, Jun 11, 2008, Feb 9 2009

- Arizona Daily Star (Tucson, Arizona), June 10, 1960, June 18, 1961, Jun 21, 1964, , Jul 24, 1970, Feb 14, 1971, Mar 26, 1978, May 19, Nov 2, 1979, Jan 22, 1982, Oct 8, 1987, May 4, 1990, May 19, 1988, Jun 28, 1992, Dec 6, 2007

- Tucson Citizen (Arizona), Aug 24, 1974

- Reno Gazette-Journal (Nevada), Apr 23, 1976

- Nick Marshall, “Ultradistance Summary,” 1981, 1982

- Ultrarunning Magazine, Nov, Dec 1981, Feb 1983, Feb 1986, Dec 1987

- Michael P. Ghiglieri and Thomas M. Myers, Over the Edge: Death in the Grand Canyon

- KSL.com, Dec 19, 2006

- Fort Lauderdale News, Aug 11, 1985

- The Signal (Santa Clarita, CA), Jul 28, 2005

- Grand Canyon History Facebook Group

- William Hafford, Arizona Highways, May 1992, “Rim to Rim to Rim: The Grand Canyon”

- Arizona Man Busted For Organizing 300-Hiker Rim-to-Rim

- Woody Harrell email correspondence, 2020