Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 19:58 — 22.5MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

During April 1879, the same month that the new American Championship Belt race was held in New York City, the second English Astley Belt race, for the “Championship of England,” was put on April 21-26, 1879, at the Agricultural Hall in Islington, London, England. While the Americans were putting up mediocre times and distances, still focusing mostly on walking during their six-day races, the Brits would run fast in this race and break 13 ultra-distance world records, proving that they were now the best in the sport. It truly was a mind-blowing race for the time.

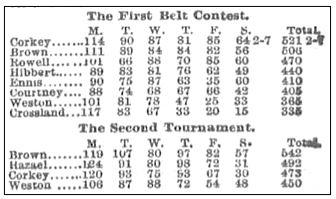

In October 1878, Sir John Dugdale Astley (1828-1894), a member of Parliament, created an “English Astley Belt,” or “Championship Belt of England” six-day race series, which had to be competed for in England. It had bothered him that his original “Astley Belt” series had gone to America for its second and third races, so he created an English Astley Belt series. The First English Astley Belt was won by William “Corkey” Gentleman, a vendor of cat food, with a world record 521 miles (see part one, chapter 17).

In England, just as in America, critics against six-day races were becoming vocal. In Nottingham, it was written, “We are to have another of those ‘wobbling’ contests, of which so many have been inflicted upon us lately. The cure of this disease rests with the public is they abstain from paying the entrance money and stay away from these useless six days’ ‘wobbles.’” At least eighteen six-day races had been held in England so far, during the past three years.

The Start

The number of people who came out to witness the early morning start of the English Astley Belt Six-Day Race in the Agricultural Hall was impressive. “One would had almost thought that the public interest in this sport would have by this time been on the wane, if not entirely exhausted, but judging from the number of persons who witnessed the start, it does not seem to have abated in the least.”

The race would be scheduled for less than 144 hours (six days), 141.5 hours. A little before 1 a.m., on April 21, 1879, the four runners were led to the starting line. Astley gave them some words of caution about fair play. Weston, always the showman, started in “a dark blue cloak with black trunks and scarlet stockings.” He looked bigger and more muscular than anyone could remember. As soon as Astley signaled, the three Englishmen sprinted away, while Weston casually walked, removing his cloak on the second lap to reveal his famous white frilled shirt. The track was measured to be eight laps to a mile.

Runner Spotlight – George Hazael

In March 1878, Hazel competed in the First Astley Belt Race but quit early with only 50 miles. In April 1878, he broke the 100-mile world record in Agricultural Hall, in London, England, with a time of 17:03:06. He also held the 100-mile walking world record with 18:08:20. In July 1878, he won an Astley championship 50-mile race at Lillie Bridge at Fulham, England, in 7:15:23. In November 1878, in a “secondary English Six Day Championship” race held in Agricultural Hall with 11 starters, he won, reaching 403 miles.

Hazael was described as having “a bulldog face, short, cropped hair and almost deformed stooped shoulders which gave him the most displeasing appearance.” He was 5’6” and weighed 122 pounds. He trained hard for six weeks prior to the current six-day race at the Sussex County Cricket Ground.

Hazael Shatters Four World Records

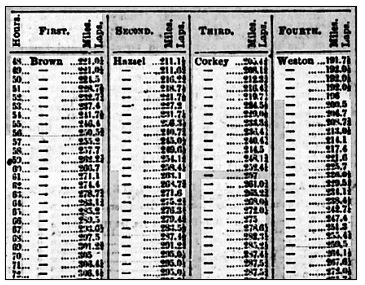

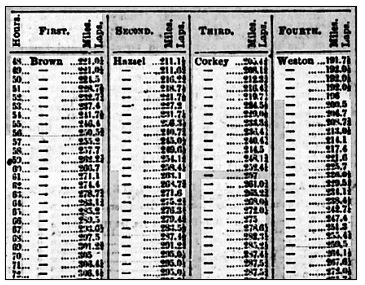

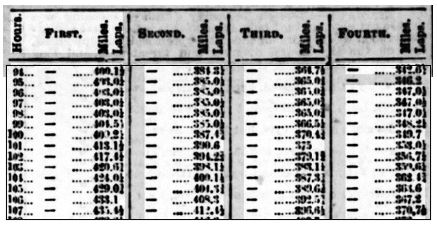

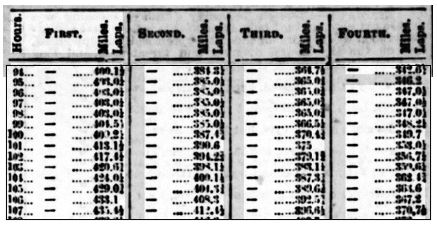

From the start, Hazael went on a tear, and clocked a 6:13 first mile compared to Weston’s 13:35. He accomplished the greatest first day running performance ever seen up to that point. He reached the marathon mark in about 3:02, stretched out the lead and reached 50 miles in a new world record time of 6:14:37. He was seven miles ahead of Brown and nearly 20 miles ahead of Weston. Hazael continued his torrid pace, fighting stomach cramps, and broke the 12-hour world record, with 80 miles, breaking the previous best held by Brown of 69 miles. Twenty miles later, he broke the 100-mile world record with a time of 15:35:31, besting his own world record time by more than an hour and a half. After the first day, Hazael set his fourth world record, reaching 133 miles in 24 hours. The previous record was 127 miles.

Where were the others after day one? Brown was in second place, with 126 miles, Corkey, 119 miles, and Weston 111 miles.

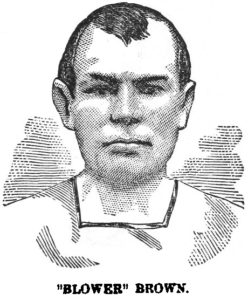

Runner Spotlight – Blower Brown

Henry “Blower” Brown (1843-1900), of Fulham, England, “the Fulham Ped,” was a brickmaker who, during his working days, would run wheelbarrows up and down planks. He was 5’ 7” and weighed 133 pounds. He had been running competitively at distances of up to ten miles since at least 1862 and won several races, including a 20-mile race at Sudbury Common, pushing a wheelbarrow.

There were multiple Browns where he was employed. Since he was stationed at the bellows, he was called “Blower.” He was described as, “Plucky and persevering, this wonderful little man has a pace exactly modeled somewhat the reputed speed of a pig, an animal which is popularly supposed to go just a little faster than anything that tries to catch it.” He finished in third at the First Astley Belt race with 477 miles and finished second in the first English Astley Belt race with 506 miles.

Brown trained hard for three months before the current six-day race, setting up his training headquarters at the Manor Tavern in Chiswick. “There was no good ground there, but a cinder track was laid down in an orchard close by, and there, day and night, Blower trained free from interruptions, under the occasional surveillance of Mrs. ‘Blower,’ the baby, and friends.”

Hazael Loses the Lead

Hazael reached 150 miles in 29:38:00, which likely was a world best for that distance. In reality, all the ultra-distance world marks were likely broken from 50 km and above if split times would have been preserved.

Hazel started to struggle. “He did not feel well on the first day, suffering from diarrhea, and in consequence had to make no fewer than six stoppages during day one which weakened him considerably. On day two, however, he managed to perk a little, and quite relished some oysters that had been procured for him. He has still confidence in his abilities to win the race” Unfortunately, his tent in the hall was pitched on the end of the building that was turning into a fair. It generated loud noises of “knock-‘em-downs, shotting galleries, bowls, bells, etc.” Corkey was hanging in there, suffering from an ulcerated tongue.

Brown Sets Nine World Records

Brown reached 300 miles in 68:32:10, setting another world record, and was handed a bouquet of flowers and two silk handkerchiefs. He then reached 306 miles in 72 hours, yet another world record, with a 16-mile lead over Hazael. On the third day, Hazael recovered and ran better, pulling within three miles of Brown, who then pulled away for good.

The work of the attendants (handlers) was impressive to watch. “There is always something wanted, and while the walker gets a rest when he leaves the track, that is just when his attendant’s attentions are most wanted.” Multiple attendants would take shifts, and when relieved, they would hang around and watch carefully that their replacements performed well. Even the lap-scorers, who were replaced at intervals, would hang about the building to watch.

Brown’s trainer (crew chief) John “Jack” Smith and Sir John Astley took Brown to Astley’s home, gave him a hot bath, and made him a nice meal of chops. Astley wrote, “Whilst I was helping Blower into his running suit, I was horrified to observe old Smith busily employed gobbling up all the best parts of the chops, leaving only the bone, gristle, and fat, and I reasoned with him on his greediness and cruelty to his man. He replied, ‘Bless yer, Blower has never had the chance of eating the inside, he likes the outside.’ Sure enough, the brickmaker cleaned up the dish.”

During day five, Hazael finally realized that overtaking Brown and winning would be impossible. “During the afternoon, some anxiety was caused as Brown, who had been trotting round in capital style for a few laps, suddenly reeled when opposite his tent, and had to be assisted in. He did not, however remain long (16 minutes) and he was again under way, apparently as well as ever. The cause of it is to be attributed to mental anxiety and excitement.” At the end of day five, the score stood at, Brown, 480 (world record), Hazael 454, Corkey 438, and Weston 399.

The Finish

Since there was really no racing going on between the men anymore, for entertainment of the 5,000 people, the band played popular songs and Weston danced and hopped around the track.

Brown broke the six-day world record at 4 p.m. and went on to crush it, finishing with 542.5 miles, in 140:21:42, in front of 14,000 people. Speeches were made and then everyone went home. Blower Brown was now the world champion six-day pedestrian. Hazael reached 493 miles, Corkey 472 miles, and Weston 450 miles. During this race, Brown set the world best distances from 48 hours to six days.

Reaction

Even though Weston came in last, a reporter for Sporting Life in London reminded readers that the sport was indebted to Weston for bringing the sport to England. “The Yankee apostle’s successful crusade in introducing his favourite hobby, and now that others are profiting by his experience, and finding an easy path to fortune over the bridge which the little man built for them, and he is eclipsed by the new lights. The new race of celebrities should never forget that but for Weston, the branch of industry would never have taken the public’s taste.”

Other Six-Day Races Held During April and May 1879

Internationally, the next big race would be the Fourth Astley Belt Race to be held in England during June 1879. But before that historic six-day race, there were at least 23 six-day races held during April and May 1879 in America, Canada, England, and Scotland. The six-day mania was clearly spreading.

The first known six-day race held in Canada was held April 7-12, 1879, at Perry’s Hall in Montreal, Canada. It was a head-to-head match won by Bart Tinnuchi, of Montreal, who went over 400 miles, beating the notorious Peter Napoleon Campana (1836-1906) of Bridgeport, Connecticut. Toronto, Canada welcomed a six-day race with 10 runners on May 19-24, 1879, won by Cyrenus Oscar Walker (1841-1919), a fisherman and bookkeeper from Buffalo, New York, who reached 434 miles.