Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 31:48 — 40.6MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

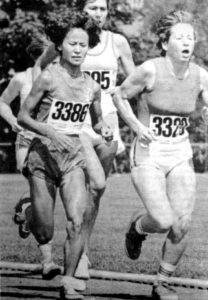

As the 1970s began, for the first time in decades, daring pioneer long-distance women athletes again joined in the 100-mile quest, with some opposition because of the lack of public acceptance for women to compete in long distances.

As the 1970s began, for the first time in decades, daring pioneer long-distance women athletes again joined in the 100-mile quest, with some opposition because of the lack of public acceptance for women to compete in long distances.

By 1970, the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) was governing American amateur running and working to prepare athletes for the Olympics. The AAU received growing criticism regarding its governance, arbitrary rules, locking out some runners, and banning women from competitions. But some races started to ignore the AAU rules and allow women to run. Most ultramarathons let them run, at least unofficially. It took a special breed of runner to push through the strong cultural gender bias to break into the male-dominated sport of distance running during the early 1970s.

As the 1970s began, 100-mile races continued in South Africa and England. They began to expand in other areas of the world including the United States, Australia, and Italy. World records continued to be lowered.

Women 100-milers

In 1869 Anne Fitzgibbons “Madame Moore” became the first known woman to walk 100 miles in less than 24 hours in upstate New York. In 1877, Carrie Parker from Illinois was perhaps the next. People believed it ruined her life and drove her to insanity. She was “a raving maniac” when she was brought before a court. “Her father testified that ever since the walking match his daughter had been suffering with great nervous prostration and recently she suddenly conceived of the idea that her whole body was charged with electricity and she would not touch her feet to the floor.” She was sent to an asylum.

Geraldine Watson – Pre-war 100-miler

Watson entered a 100-mile road race organized in Durban, South Africa in 1934. The race was held on a circular road course. Watson ran a sub-24-hour 100 on June 30, 1934. Her time was 22:22:00 and was performed in strong gusty winds and rain. Two men also finished the race, Fred Wallace with a time of 16:52:20 and Bill Cochrane (1900-), with 17:25:00.

Miki Gorman – 100 Mile World Record Holder

During October 1969 the runners would post their laps on the wall of the club each day. Gorman explained, “That’s how I started as I am a very competitive person. I was the last person after the first week. Then I got more interested and by the end of the month, I was in second place among the women.”

Gorman started serious training. She was trained by Mihaly Igloi (1908-1998), a Hungarian distance running coach and former Olympian. “He didn’t let us stop. We were always jogging. We had a hard time understanding each other. He would have us do an easy jog, then shake out strides, then some at eighty percent. Then we would do repeats for two miles, then 150 yard runs, then some jogging that got faster.”

Natalie Cullimore – 100 mile World Record Holder

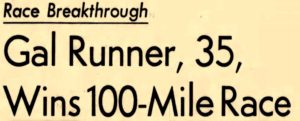

Two months later she ran her first ultra, the National AAU Road 50 Miles Championship, in Rocklin, California on a road course. The race included ultrarunning legend, Ted Corbitt. She finished first in 7:35:57, setting an American women’s record. A reporter wrote, “The race became even more amazing when a gal, Natalie Cullimore, finished the whole route to wind up 18th and beat a lot of males in the process. These people who run 50-mile marathons are a funny breed. And they don’t get paid anything for it either. Well, to each his own.”

Mavis Hutchison – 24-hour World Record Holder

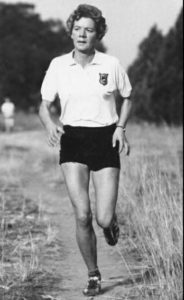

Hutchinson started training at the age of 37, at the encouragement of her sons and began her running career as a race walker. Her health greatly improved. She attempted her first 50-miler in 1962 which she said was a disaster. She quit after 16 miles.

So Hutchinson began running. She ran in the Johannesburg Marathon, the only woman among 75 men and the first known woman to run in a marathon race in 37 years. “The officials were not especially enthused but allowed her to run ‘unofficially’ perhaps because a woman who could racewalk 80 km in record time was unlikely to embarrass them by collapsing.” She finished with a marathon time of 3:50, the second fastest time on record. That was four years before Katherine Switzer’s famed finish at Boston and it was a half hour faster.

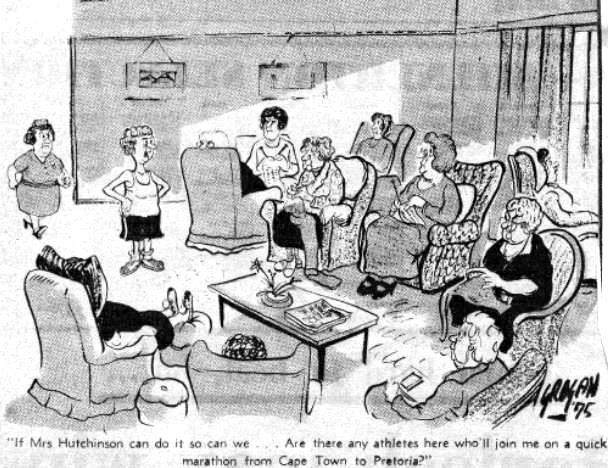

But Comrades was actually too short to bring out the best in Hutchison. By 1971, at the age of 46, she was ready for a greater challenge – a 24-hour race on a track at Hector Norris Park in Johannesburg. She put in three months of intensive training including hours after work and eight hours a day on weekends and mostly on a track. She explained, “I sometimes did a bit of road work, but people passed remarks and some men even tried to pick me up, until they saw my gray hair.”

Twenty-four-hour record holder, Wally Hayward was the starter for the race. Hutchison ran well. “As she ran endlessly around the track under the hot afternoon sun, the naysayers saw Mavis start to set new records for women, first for 25 miles, then for fifty. She was running strongly as night fell, keeping a steady pace in her tracksuit.” But as with most rookie 100-milers, she had not yet learned how to eat well along the way.

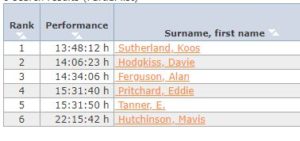

By 21.5 hours, her crew realized that she could break the time set by Geraldine Watson in 1934 of 22:22:00. More recently, in 1963, Cathy Burgess had reached 100 miles 22:46:00 at Cape Town, South Africa. Hutchison beat both those time with a “world record” of 22:15:42. (However, her time was far off Cullimore’s 100-mile road time of 16:11:00 and Gorman’s indoor track time of 21:04:04, accomplishments in America that they certainly did not know about.)

But Hutchison wasn’t finished, she intended to claim the world record for 24 hours. When the clock reached that point, she had covered 106 miles, 736 yards, indeed a new world best. She commented, “Surprisingly, afterwards I did not feel exhausted, though the tops of my legs were sore.”

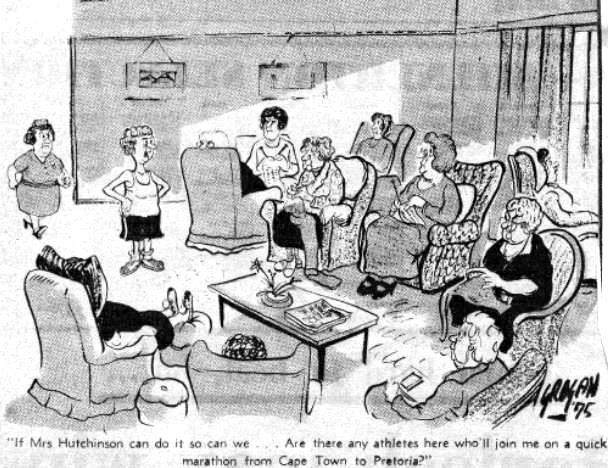

Some men in her club were unhappy and even some women had some cruel things to say. Hutchinson said, “It was hard to cope with the gossip that followed. I became very distressed about it. But I guess that was to be expected since I had already faced similar nastiness from those who thought I was press hungry. No doubt they don’t realize the time and hard work involved. It’s just as well I don’t mutter when I’m running.” The negative reaction from her club caused her to resign and join another club.

Her last competition was the World Masters Championship in Brazil in 2013. In 2020, Hutchinson was 96, living in Cape Town, South Africa.

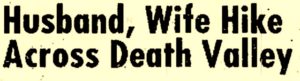

First woman to hike across Death Valley

She said, “Seven men have crossed it the way we went. I am the first woman to cross and that is more or less an official record.” Their route went from Shoshone to Scotty’s Castle. They were accompanied by a photographer who drove a jeep and trailer with supplies. “He would drive on about two or three miles ahead of us and we would stop at the jeep to get water and rest. We traveled at night and the majority of it in the evening. At night all you can see was the flashlight and the stars. It was like you were down in a big hole and all around you all you could see is big peaks.”

“At first we would go for 16 miles and sleep for four hours during the night. Toward the end we kept going all day. I wanted to get to the end. I just couldn’t take the heat. I got tremendously tired because the wind was blowing in our faces. You begin to hate Death Valley by the end.” The temperature reached a high of 125 degrees and a low of 98.

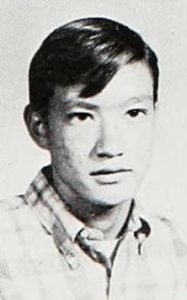

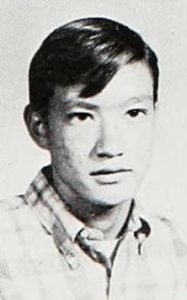

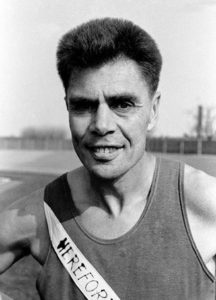

Jose Cortez – 100 Mile American Record Holder

Cortez trained 90-110 miles per week (or more, depending on upcoming race), 6-7 days per week, 11 months per year. His longest ever training run up to that point was 31 miles.

Cortez said, “I owe a great deal of my running success to Mike Ipsen, who has really built up my mental attitude for the longer races and a greater confidence within myself. The method of training which has proven to be the most successful to myself is of the quantitative type. My daily workout basically consists of a long and easy paced run, except while preparing for an important race. At this time I would increase my weekly mileage and would switch to a double workout. The morning (or else evening) run would be from 6 to 8 miles at fairly good pace. The mid-day workout would range from 12 miles on up at a pace set according to the way I feel. I am definitely a back-runner. During races I prefer to run behind my competition, letting them set the pace until I feel that I can overtake them and maintain a lead. Racing like this allows me to run under less pressure and to keep my body more relaxed. This is essential to me in a long race.”

Historic 1971 100-Mile Race at Rocklin, California

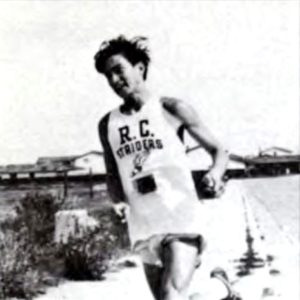

The race was held in the Sunset-Whitney Ranch development with 17 runners including women and started a little before noon. A 2.5-mile asphalt loop course was set up with the start/finish in a golf course parking lot. Street lights provided enough light to run at night.

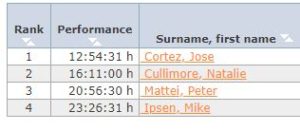

Cortez and Darryl Beardall ran the first 25 miles together before Cortez began pulling away. Beardall eventually dropped out after 50 miles in 6:09:51 because of recurring breathing problems that have plagued him over the past year. Cortez, who hit 50 miles in 5:52:13, was also paced for the first 50 miles by his younger high school running buddy, Randy Lawson. Cortez thought Beardall would win the race and he had hoped to just keep Beardall in his sights, but after Beardall dropped out, that spooked Cortez to go on alone. But he did very well, hallucinating over the last 10-15 miles, and completed a historic run. He set an American road 100-mile record of 12:54:30, besting Ted Corbitt’s track record of 13:33:06 set in 1969 (see episode 63). (As with other road races of that time, the course was never certified).

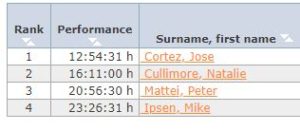

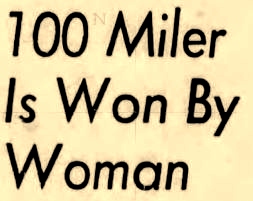

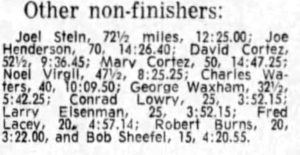

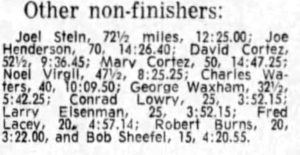

Cortez’ 100-mile record stood for the next 13 years. Natalie Cullimore came in second with 16:11:00. Pete Mattei of San Francisco came in third with 20:56:30. He ran well for many miles but then was besieged by stomach problems which required him to take periodic rests. Mike Ipsen was the final finisher with 23:26:31. Thirteen other starters failed to finish. Ipsen said the race could have been called, “One-Hundred Miles of Sheer Stupidity.”

Cortez was listed as one of the nation’s top US male track athletes in the 1972 Runners’ Almanac. He had his eyes on the Olympics but cramped up during the Olympic trials won by Frank Shorter. Cortez finished in a disappointing 38th. He only ran a few more marathons and ultras in his 20s . In 1998 at the age of 46, he surprisingly returned to ultras and ran in the Jed Smith 50-miler in Sacramento California, placing 5th with a time of 7:48:08. Rae Clark won and Ann Trason came in 3rd place, but no one probably knew he was a former American 100-mile record holder. In 2020, Cortez was 68 years old and living in Freemont, California.

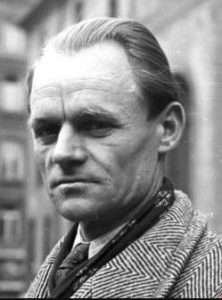

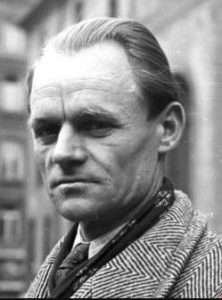

George Perdon of Australia

During World War II, he served in the army and looked forward to the 90-mile marches that he participated in during the war in the Pacific Island. After the war he started to run and competed on the track, ran in cross-country meets and marathons.

Perdon was a professional runner. As a young man he played some professional football (soccer), which ruled him out of amateur running competition. But he ran for the love of it, not for the little money that he made because of it.

George Perdon’s 100-mile World Record

The PCCC secretary, Bruce Duncan (1928-2005) said, “It is the first professional 100-miles championship of Australia.” Perdon was the favorite. Four other runners entered, including decorated ultrarunning brothers, Ian Colston and Neil Colston, Bob Hunter, and Robert Petrie.

Perdon never achieved his goal to break the 24-hour world record but in 1973 he gained huge fame by being the first to run 3,000 miles across Australia. It took him 47 days beating his rival Tony Rafferty. On June 29, 1993, Perdon, who had run about 200,000 life-time miles, died at the age of 68 after a long battle against cancer.

1970 100-mile Race in South Africa

On July 31, 1970, the Durban 100 Miles Track Race was again held in South Africa. It had been held every two years since 1968. Both John Tarrant (1932-1975) “the Ghost Runner” and Dave Box (1929-2015) were determined to reclaim the world record. Tarrant and Box trained together. “Every evening, they kept up the ‘hell run’ back through the thunderous stink of the docks, and at weekends the two men ran up to fifty non-stop miles before plunging into the ocean at Brighton Beach for cooling late-afternoon swims.”

Tarrant, still banned from races in South Africa, turned out illegally as a ghost at many races. He would be chased, vilified, abused and ignored, but no one had yet pulled him from a race. As the 100-mile race came closer, his enemies turned up the heat and it was announced that he would be banned from the race and pulled off the track. Any athlete competing alongside him risked being banned for life.

Tarrant believed that all the threats were a bluff. He arrived at Kings Park on July 31st, intending to run. Stan Foley, the chairman of the race confronted him with a heated exchange. Tarrant offered to run in a separate lane, but Foley was firm. He recalled, “I personally had huge sympathy for Tarrant. Some of us had tried to help him find work at various times, but he was a very, very pig-headed man at that time.” John Jewell of the Road Runners Club in Britain had confirmed that Tarrant could not be allowed to compete. So, for the first time, “the ghost” has been stopped, all because he had taken a few pounds at a boxing match when he was a teenager. Tarrant went to Box and wished him luck.

Box said, “I wanted John to run. I wanted to prove I was better than him, and he wanted to do the same. I wanted to run against the best but I couldn’t. It was bloody tragic. If he’d been in that race, I’d have run even faster.”

The race started at noon with at least ten starters. Box indeed broke the 100-mile world record with a time of 12:15:09. He beat Tarrant’s former record by 16 minutes. Tarrant had stayed to watch and help crew another runner. He put on a positive face and said, “In the passing of time, we all become ex-world champions,” but it actually hit him hard.

24 Hours in Italy

During 1971 two 100+ mile performances were accomplished in Italy. On May 9, 1971, Andreino Invernizzi reached 127 miles in 24 hours at “24 hours of Lecco on the track” at Lecco, Italy. Previously in 1970 he reached 112 miles in the save event. On October 17, 1971, Enzo Boiardi reached 132 miles at “24 hours of Piacenza on the track” at Galleana Stadium, in Piacenza, Italy setting an Italian record.

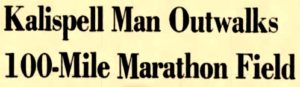

100-Miles Walking Indoors

100-Mile Relay

100-mile journey runs

Rain and cold air bothered them and they cramped up along the way. At mile 20 their legs began to feel like “lead pipes.” They were forced to stop many times to get their legs massaged by their coach driving along with them.

Many passing motorists offered to give them rides. “Fred was unable to digest any of the food he swallowed while running and became nauseated.” At night after getting a drink at a closed gas station, a policeman stopped the suspicious-looking young men briefly to question them.

They admitted their spirits lagged as they realized they could not break 20 hours and they finished in a little less than 26 hours. Fred at first said he would never attempt another 100-mile run, but later commented, “Well, maybe another time.”

In March, 1970, a 17-year-old high school student, Irvin Goldenberg, from University City, Missouri ran 100 miles on a track in 22:55. Friends said they urged him on through periods of happiness and depression. A companion had to quit after 55 miles.

The parts of this 100-mile series:

- 54: Part 1 (1737-1875) Edward Payson Weston

- 55: Part 2 (1874-1878) Women Pedestrians

- 56: Part 3 (1879-1899) 100 Miles Craze

- 57: Part 4 (1900-1919) 100-Mile Records Fall

- 58: Part 5 (1902-1926) London to Brighton and Back

- 59: Part 6 (1927-1934) Arthur Newton

- 60: Part 7 (1930-1950) 100-Milers During the War

- 61: Part 8 (1950-1960) Wally Hayward and Ron Hopcroft

- 62: Part 9 (1961-1968) First Death Valley 100s

- 63: Part 10 (1968-1968) 1969 Walton-on-Thames 100

- 64: Part 11 (1970-1971) Women run 100-milers

- 65: Part 12 (1971-1973) Ron Bentley and Ted Corbitt

- 66: Part 13 (1974-1975) Gordy Ainsleigh

- 67: Part 14 (1975-1976) Cavin Woodward and Tom Osler

- 68: Part 15 (1975-1976) Andy West

- 69: Part 16 (1976-1977) Max Telford and Alan Jones

- 70: Part 17 (1973-1978) Badwater Roots

- 71: Part 18 (1977) Western States 100

- 72: Part 19 (1977) Don Ritchie World Record

- 73: Part 20 (1978-1979) The Unisphere 100

- 74: Part 21 (1978) Ed Dodd and Don Choi

- 75: Part 22 (1978) Fort Mead 100

- 76: Part 23 (1983) The 24-Hour Two-Man Relay

- 77: Part 24 (1978-1979) Alan Price – Ultrawalker

- 79: Part 25 (1978-1984) Early Hawaii 100-milers

- 81: Part 26 (1978) The 1978 Western States 100

- 87: Part 27 (1979) The Old Dominion 100

Sources:

- The Age (Melbourne, Australia) Aug 16,30 1965, May 27, Jul 23-24, 1968, May 19, 25, June 18, Sep 19, 21, 1970, Jun 20, 1979, May 22, Jun 30, 1993, Sep 16, 1994

- Bill Jones, “The Ghost Runner: The Epic Journey of the Man They Couldn’t Stop.”

- Andy Milroy, “24hr Run History”

- Red Bluff Daily News, “She Ran 85 Miles As They Ran Around the World in One Month.” Jan 8, 1970

- The Sedalia Democrat (Missouri), Mar 29, 1970.

- The Fresno Bee (California), Nov 2, 1970

- The Daily Inter Lake (Kalispell, Montana), Dec 23, 1970

- Associated Press, “Runners Claim Records For 100-mile Marathon,” Dec 3, 1970

- Albernie Valley Times (Canada), Dec 3, 1970

- Petaluma Argus-Courier (California), Apr 24, 1971

- Kensington Post (England), Jul 2, 1971

- Elk Grove Herald (Illinois), Aug 11, 1971

- The Los Angeles Times (California), Aug 27, 1971

- The Times (San Mateo, California), Oct 6, 1971

- The Sacramento Bee (California), Mar 15, 1971. Mar 8,12, 1973, Jan 20, 1977

- The Honolulu Advertiser (Hawaii), Sep 16, 1971

- The New York Times (New York), Oct 30, 2005

- Miki Gorman interview by Gary Cohen, 2014

- David and Gillene Laney, Unstoppable Woman: The Forgotten Story of Mavis Hutchison

- usacrossers.com

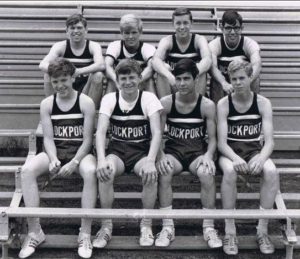

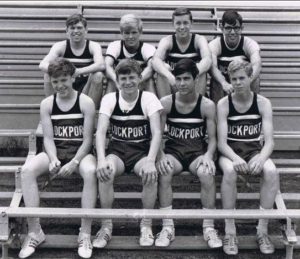

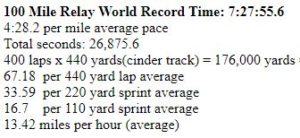

- 100 Mile Relay World Record (8 runners) 7:27:55.6 – June 16, 1968 – Lockport Track Club

- Jose Cortez thoughts, Dec 2020 video “50th Anniversary Rocklin Race” conducted by Gary Corbitt

- NorCal Running Review, April 1971

- Long Distance Log, April 1971