Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 30:34 — 37.0MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

Part 1 and Part 2 of this 100-mile series covered the stories of remarkable long-forgotten ultrarunning pioneers. By 1879, a remarkable shift started to take place. The most elite professional 100-mile walkers and runners became focused on competing in indoor six-day races for huge prizes and fame. That year more amateurs entered the sport and attempted to run or walk 100 miles for wagers or for nothing at all.

![]()

![]()

A Pennsylvania newspaper reported, “One of the most absurd manias that has recently afflicted humanity is the pedestrian craze which at present disturbs the mental balance of several cities in the interior of this state. The pedestrian craze infects lawyers, tradesmen and physicians. Half the population walk habitually on a dog-trot, and the police are instructed to see that amateur matches on the public streets do not interfere with the transaction of business. To what purpose is this waste of energy and enthusiasm?”

![]()

![]()

Ultrarunning historian Andy Milroy commented, “Dan O’Leary’s 1877 and 1878 six-day wins in London created a huge stir in the US. It inspired ordinary people to undertake Pedestrianism. Most could not afford the time to tackle a six-day, or even a 50-miler. That was beyond them. So, they became fixed on the 25 mile distance. There was an explosion of such events, newspapers wrote of a plague of such events gradually spreading out from New York.”

For the successful ultrarunners of the time, the financial impact on their lives was significant. There has never been an era in ultrarunning when being a professional impacted so many runners and brought in so much money. The amount that was successfully won in one race could be the equivalent of a lifetime’s earnings. Managing that wealth was another challenge. Edward Payson Weston won an enormous amount of money during this era but lived a lifestyle where he spent more than he brought in. He missed some key international events because he had to deal with legal troubles involving his finances. All this potential wealth also attracted greed and the potential for fraud. This article will include stories of that side of the sport.

1879: 100-mile craze continues

The 100-mile craze occurred mostly in America, but was also pursued at times in England and Australia. Those entering the sport included people such as Henry E. Nutting, a member of Boston’s YMCA gym, Charley Joe, a native American from Michigan, postmen, mothers, and many young men in their early twenties.

100-milers in America

In March,1879, a historic 100-mile race was held at the Douglass Institute (named after Frederick Douglass) in Baltimore Maryland. The Douglass Institute hosted countless meetings of organizations promoting African American causes. This race was a unique contest for a couple reason. First the course was on a very tiny track with 52 laps to a mile on a hard floor with some sawdust sprinkled on it. That was only about 34 yards per lap! But more importantly, the two contestants were black, Isaiah Hawkins, age 41, and his nephew James Williams, age 19. Hawkins had no previous walking or running training. The race was planned to last 26 hours and the prize was for $100. After 5.5 hours, the race was close with Williams at mile 21 and Hawkins at mile 20. After 26 hours, Williams was declared the winner with 89 miles. Hawkins reached 85. The attendance to witness the race was fair.

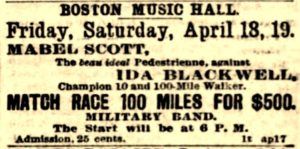

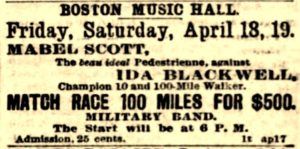

A large crowd gathered to witness the start despite a terrible storm outside. The track was twenty laps to a mile. News coverage described the clothing they wore more than the details of the race. “Miss Scott’s hair was arranged in a twist with a single white rose on the left side.”

Blackwell took the early lead but Scott caught up as Blackwell took rests. “A fine band of music was present, and added to the enjoyment of the spectators as well as cheered the walkers. After 20 miles, Blackwell’s ankle began to trouble her. Scott took the lead at mile 23 but accidentally hit her left ankle against an iron post which caused it to swell up. Blackwell finally quit at mile 70 when she was 12 miles behind. The race was finally called at 27:54:09 when Scott had completed 89 miles. She quit once a 50-miler race was arranged between the two for the next month. Blackwell won that race by two miles.

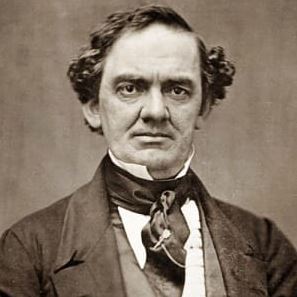

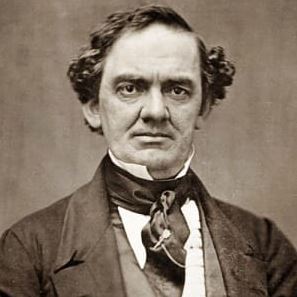

P. T. Barnum

A New York City block, where present-day New York Life Building stands on Manhattan, was the scene for a decade of many 100-mile and six day races. P. T. Barnum (1778-1826) of circus fame entered the Pedestrianism scene. Few realize that Barnum was an ultrarunning pioneer.

Barnum began his career as a showman in 1841 when he established “Barnum’s American Museum” on Broadway at New York City. His fame and fortune grew and in 1870 he established a traveling circus, menagerie, and museum of “freaks” called, “P. T. Barnum’s Travelling World’s Fair, Great Roman Hippodrome and Greatest Show on Earth.”

The Hippodrome

On March 1, 1875, he put on the first formal six-day race in America. It was a $5,000 match race between Edward Payson Weston and Professor Judd. During this historic New York race, Judd gave up on the fourth day with sore feet. Since the event was no longer a competition, just Weston walking, Barnum realized that he needed to keep spectator interest. He allowed other walkers to take Judd’s place against Weston. Weston wasn’t happy about having other walkers share the stage with him and toward the end he demanded that the other walker be removed which caused “considerable dissatisfaction among the rowdy element in the audience.” Weston reached 431 miles in this first American six-day race.

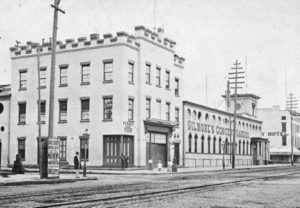

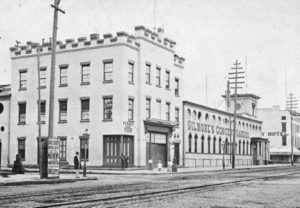

Gilmore’s Garden

William Henry Vanderbilt (1821-1885) actually owned the property and after the circus vacated that year, band leader Patrick Gilmore (1829-1892) leased the property for concerts, flower shows, beauty contests, dog shows, and boxing matches. The venue was renamed to Gilmore’s Concert Garden. A permanent roof was finally added around 1876. It became one of the most popular venues in the city and eventually in 1879 was renamed to Madison Square Garden.

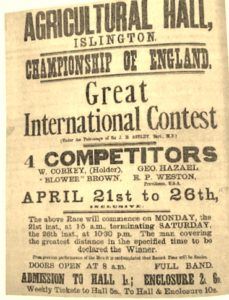

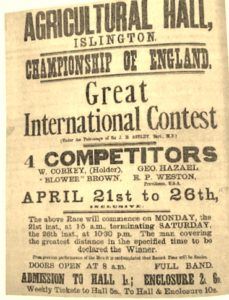

George Hazael

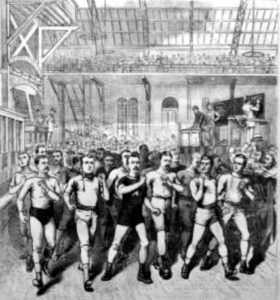

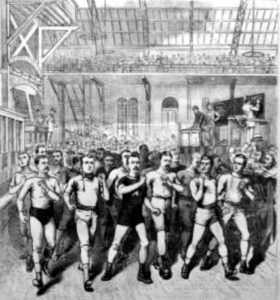

In April 1879, a six-day “Championship of England” was held at the Agricultural Hall in Islington, London England. Contestants included famous Pedestrians, Edward Payson Weston, William Corkey, Blower Brown, and George Hazael of England. Hazael had been training hard for this race at the Sussex County Cricket Ground near Brighton.

By mid-day at mile 75, his potentially suicidal fast pace started to take its toll and he had to lie down for 22 minutes because of stomach cramps. He was slower when he resumed but, quickly made up for the two miles that the others cut into his lead.

“Hazael still continued to widen the gap between himself and the others during the afternoon. A most unprecedented performance was recorded, namely the accomplishment of 100 miles by Hazael in 15:35:31, thus beating the fastest time for that distance by 1:28:35.” (Hazael had set the previous record of 17:03:06, also at Agricultural Hall about eight months earlier.) Hazael went on to finish second in the six-day race with 492 miles, but had established himself as the world’s best 100-mile runner.

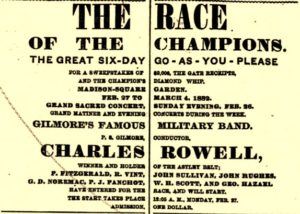

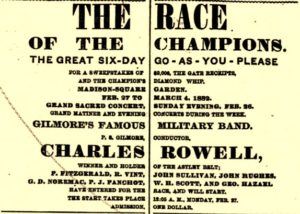

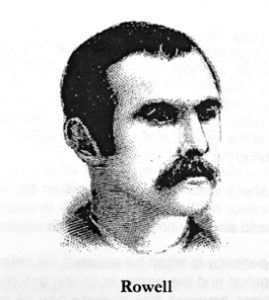

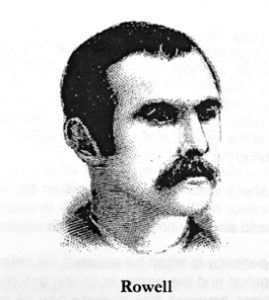

Charles Rowell

But soon Charles Rowell (1852-1909) would take over the crown as the fastest 100-mile runner of the 19th century, when he ran in the International Pedestrian Six-Day Contest held November 1880 in Agricultural Hall, in London.

Charles Rowell was born in Chesterton, Cambridge, England and was sometimes known as “the Cambridge Wonder.” He had been hired as a pacer for Weston, but later competed on his own. He soon won two world championship six-day races with at least 500 miles. Unfortunately for this race, the weather in London had been very poor, preventing training outdoors leading up to the race. George Littlewood (1859-1912) of Attercliffe, Yorkshire, England was a speedy newcomer running in his first six-day event.

Two others in this race also beat the previous 100-mile world-best, John Dobler with 14:52:48, and Littlewood with 15:19:30. John Dobler (1859–1943), age 21, was an Austrian-American from Chicago Illinois. His 100-mile time crushed the American record by about 3.5 hours. His trainer was none other than the legend, Daniel O’Leary. A reporter at the race commented, “Rowell’s 100-mile performance is a most marvelous one, and far exceeds anything ever attained in long-distance pedestrianism, while Dobler’s efforts are also far in excess of record.”

Rowell said, “I feel in first rate condition. I think I may give my competitors some trouble before they beat me.” Asked about his race strategy, he replied, “I go according to what the other men are doing. My game is to beat the other men. I shall eat oatmeal, beef, tea, chicken, broth, eggs, chops, oysters, and nourishing food of that kind. My drink will be ginger-ale and sometimes bottled cider. I have no regular hours of eating, but eat when I am hungry – that is pretty much all the time.” When asked how far he planned to run the first day, he replied 150 miles. “My best first day’s record is 146 miles in less than 24 hours.”

Right before the race, vendors were stationed at the Madison Avenue entrance trying to sell their wares shouting, “Lives of all the walkers” and “program of the race.” An hour after the doors were open, 6,000 people were in the building with hundreds still waiting in line. The bookmakers with tin boxes sat at small tables operating near the scorers, taking bets. Rowell was a 2-to-1 favorite.

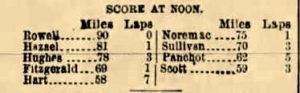

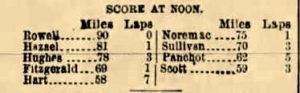

The race began as 12:05 a.m. in front of 10,000 cheering spectators. Gilmore’s 50-piece band was hired to perform music during the race. After four hours, Rowell took the lead followed closely by Hazael. With the cramped track, some runners issued protests to the referee because of bumping taking place or they felt that their progress was being impeded by runners in the way. The referee took charge and made the participants stop complaining.

Newsboys woke up citizens at all hours of the night shouting the latest reports from the race. Bulletins were displayed on walls and dining windows in every block. “Tens of thousands of people, mostly fools, were eagerly asking, ‘Who’s ahead?’”

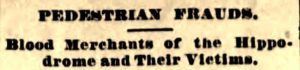

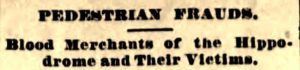

100-mile fraud

![]()

![]()

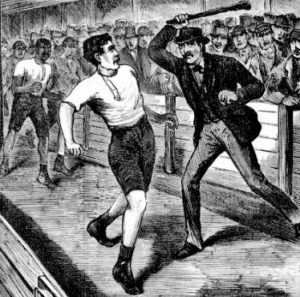

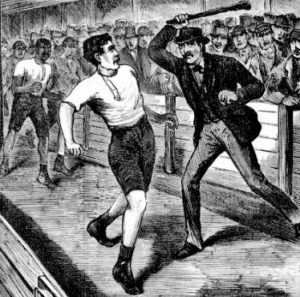

With high-stakes wagering, at times greed motivated investors to take things into their own hands. At Reading Pennsylvania, Samuel Mishler was attempting 100 miles. After 15.5 hours at 70 miles, he asked for a drink of water. “Mr. Mishler says that a glass of water was handed him and that it had been drugged, for he was unable to continue to his walk. Others say he dropped to the floor in a swoon. He did not recover from the effects of the drug for several hours afterwards. When asked whether he though he had been intentionally drugged, he answered ‘Yes, because there was considerable money at stake.’”

The prolific 100-miler M’lee Dupree didn’t trust the time-keepers during her matches. She would mentally keep a record of every lap she completed and also what her competitors were doing. “In this way she was able to confirm the time-keepers’ work whenever she chose and often did so.”

Von Blumen finished her 100-miles as promised. “Miss Von Blumen made a good impression upon her audience. She is good-looking, and lady-like, full of pluck, and possesses great powers of endurance. She was neatly and appropriately costumed and walks quite gracefully.”

At York Pennsylvania, Nelson performed in a 100-mile match at the Laurel Engine House, trying to reach that mark in 30 hours. He was to push a wheelbarrow for the last 18 miles. He made it to mile 96 and suddenly quit, claiming that he could continue no longer. Fraud was suspected.

![]()

![]()

In 1885, Professor Loring advertised widely that he would be walking 100 miles in 23 hours at Greenleaf, Kansas. A large crowd showed up to watch, but Loring failed to appear. “It was noised around that Professor Loring was a big fraud. The management of the skating rink refunded the money to those who had gone to see him and at last accounts they were hunting for the aforesaid Loring with the City Marshall.”

100-mile interest wanes

With each passing month in 1879, public interest was waning and crowds reduced. One newspaper column commented on how the world had thought it was amazing when Weston had walked 100 miles ten years earlier in 1868. “But no one thought that in so short a time would his feat be considered a very ordinary affair. And now women have become imbued with the craze. Every female in the country has set to show what she can do. For no other reason than that of the notoriety gained. But it is time to drop it. Give us a rest. Why do not some of these persons who want to show their powers of endurance tackle a woodpile and see how many quarter cords they can saw in a certain number of quarter hours? There are a number of things they could do and should do.”

At Rutland, Vermont, Marie Vernon began a walk at an Opera House but quit “disgusted” because the audience was so small and she knew she would not make very much money. Her brother took her place to at least fill the obligation. It was reported, “Speculative walkists will no doubt give this place a wide berth in the future.”

At Saint Paul, Minnesota, a highly publicized 100-mile race was a failure as one of the contestants just didn’t show up. The other walker reached 100 miles in 23:45 but the event received little attention and a sparse audience.

Critics

Watching two men who had walked 400 miles in a week was compared to seeing boxers who had pounded on each other’s faces for three hours with their fists. “There is no grace, beauty or true manliness in them. The men who take part are on the intellectual, moral and physical level of prize-fighters, and it is hard to see wherein such matches are superior to the battles of the ring. In both it is merely a question of the man who can stand the most suffering and still keep on his legs. What single good purpose was ever served by one of these degrading and brutal exhibitions?”

Violence and tragedies even occurred with the women pedestrians. At Westfield, Massachusetts 100-mile match, a competitor grabbed the hair of Anna Berger “and the struggle became one of hands instead of feet.” At Milwaukee, Wisconsin, May Fanning fainted on the track and lay for two days in a stupor.

Six day races were opened up to women in 1879 when a women’s race was held that year at Gilmore’s Garden with 18 women who were required to wear full-length dresses. Bertha Von Berg won with 372 miles. The press said that race was “public torture of women.” It was called “one of the most brutal exhibitions afforded the public in some time.” Soon New York City banned “all public exhibitions of female pedestrianism.”

Why did these 100-milers do it? “Any reputation or popularity he may secure is extremely short-lived, and is confined to the lowest classes. With few exceptions they are handled by ‘backers’ who have them wholly in their power, who put up the stakes, pay the expenses, pocket the profits and too often sell out their men. The sooner we see the end of these races, the better.”

People could even detect the impact that these grueling events had on their American hero, Daniel O’Leary. After some sickness when he still competed in a race. It was written, “It was evident to every critical spectator that he had broken down and was fast weakening. He hardly walked a single yard without swerving from side to side, his steps describing a zigzag course. If you were to see him, you would be surprised. He is thin. His legs are not half so big as they were. He hadn’t the flesh to carry him through, let alone the vital force.”

During that six-day event in March 1879 at Gilmore’s Garden, O’Leary quit after 215 miles. “He looked like a corpse. His face was terribly flushed, and his neck and chest were as red as a beet. He was the personification of a man who had walked himself to death.” Rumors flew around that city that after he was taken to a hotel, he died. But he did not. He recovered, but soon retired from the sport.

100-miler retirees

In May 1879, professional 100-miler Edward E. Miller could not find a challenger to race with him. He wrote in the newspaper, “I will now challenge the public at large to compete with me in the manufacture of a select article of either ice cream or lemonade. I agree never to be out of ice cream which will be on sale every day of the week by the gallon, quart, or dish.”

By 1880 many 100-milers evolved into novelty acts associated with fairs. The 100-mile attraction had worn off. There were much fewer 100-mile accomplishments mentioned in the newspapers.

By 1881, John Ennis, the well-known pedestrian from Chicago also could not find challengers, so he turned to 100-mile ice skating. He defeated Rudolph Goetz a champion long-distance skater from Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Ennis reached 100 miles on very rough ice, seven miles before Goetz, winning $100. His time for the 100-miles was 10:57.

Edward Payson Weston’s Christmas 100-miler

He started at 10 p.m. “As in former days, he walked with the same sprightly tread and carried a whip. As he made the first circle around the track, he was loudly applauded. He finished the first five miles in 58:20 and when this announcement was given out, he was again liberally applauded.”

Skaters still went around on the ice. He told his doctor that his legs below his knees had gone to sleep but this had happened before and he wasn’t concerned. “During the night Weston ran and walked alternately, and now and then reversed his way of going around the track. The coolness of the atmosphere in the Ice Palace did not appear to trouble him in the least.”

In the morning, the skaters returned to the rink. “They livened the veteran pedestrian very much. Some of them would skate around the edge of the rink, keeping abreast of Weston, who chatted and joked with them.” At 15 hours he took his first rest. “During that time, he had eaten lots of eggs and calves’ foot jelly and drunk beef tea, milk and coffee. While he was off, he had a bath and changed his clothes.”

After 19 hours, Weston’s strength faltered and a dizzy spell overpowered him. “He was assisted from the track as weak as a baby.” His doctor worked on him and “soon the wonderful old man was up again and asking what it was all about.” The doctor made him rest for nearly an hour. “He then appeared somewhat discouraged, but was cheered on by numerous friends. He soon struck his old-time gait and kept up bravely to the end.” Weston succeeded and reached 100 miles in 23:56:30.

100-mile 19th century craze concludes

During the 1890s, 100-miler distance walkers returned to the outdoors and at times outrageous stories were printed in the newspapers. In July 1896, two men in Illinois walked 100 miles from Chicago to Rockford without stopping for food or rest. “Both are hypnotists, and they claimed that they hypnotized each other and imagined they were riding. This might be very useful to bicycle tourists whose wheels break down when they are at a distance from a repair shop or railroad station. But it is a little singular that two men should be able to hypnotize each other. How can that be possible?”

How many people finished 100-milers during the 1800s? I estimate there were likely more than 400 finishes in less than 30 hours and the vast majority were less than 24 hours. Competitive 100-mile races took a hiatus at the turn of the century as attention turned to covering 100 miles on bikes, horses, or automobiles.

The parts of this 100-mile series:

- 54: Part 1 (1737-1875) Edward Payson Weston

- 55: Part 2 (1874-1878) Women Pedestrians

- 56: Part 3 (1879-1899) 100 Miles Craze

- 57: Part 4 (1900-1919) 100-Mile Records Fall

- 58: Part 5 (1902-1926) London to Brighton and Back

- 59: Part 6 (1927-1934) Arthur Newton

- 60: Part 7 (1930-1950) 100-Milers During the War

- 61: Part 8 (1950-1960) Wally Hayward and Ron Hopcroft

- 62: Part 9 (1961-1968) First Death Valley 100s

- 63: Part 10 (1968-1968) 1969 Walton-on-Thames 100

- 64: Part 11 (1970-1971) Women run 100-milers

- 65: Part 12 (1971-1973) Ron Bentley and Ted Corbitt

- 66: Part 13 (1974-1975) Gordy Ainsleigh

- 67: Part 14 (1975-1976) Cavin Woodward and Tom Osler

- 68: Part 15 (1975-1976) Andy West

- 69: Part 16 (1976-1977) Max Telford and Alan Jones

- 70: Part 17 (1973-1978) Badwater Roots

- 71: Part 18 (1977) Western States 100

- 72: Part 19 (1977) Don Ritchie World Record

- 73: Part 20 (1978-1979) The Unisphere 100

- 74: Part 21 (1978) Ed Dodd and Don Choi

- 75: Part 22 (1978) Fort Mead 100

- 76: Part 23 (1983) The 24-Hour Two-Man Relay

- 77: Part 24 (1978-1979) Alan Price – Ultrawalker

- 79: Part 25 (1978-1984) Early Hawaii 100-milers

- 81: Part 26 (1978) The 1978 Western States 100

- 87: Part 27 (1979) The Old Dominion 100

Sources:

- Barnum’s freaky link to Madison Square Garden

- The Western Spirit (Paola, Kansas), May 1, 1874

- The Brooklyn Sunday Sun (New York), May 17, 1874

- The Luzerne Union (Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania), Sep 23, 1874

- The United Opinion (Bradford, Vermont), Oct 3, 1874

- Matawan Journal (New Jersey), Dec 5, 1874

- The Valley Sentinel (Carlisle, Pennsylvania), Aug 30, 1878

- Rutland Daily Herald (Vermont), Feb 12, 14, Apr 25, 1879

- Reading Times (Pennsylvania), Jan 23, 1879

- The Boston Globe, (Massachusetts), Jun 30, 1878, Feb 8, Apr 18-20, May 19, 1879

- The Muscatine Journal (Iowa), Oct 11, 1879

- The Lake Geneva Herald (Wisconsin), Feb 8, 1879

- The Morning Democrat (Davenport, Iowa), Apr 17, 1879

- The Saint Paul Globe (Minnesota), Apr 7, 1880

- Fayette County Herald (Washington, Ohio), Jul 3, 17, 1879

- Public Ledger (Memphis, Tennessee), Feb 27, 1879

- Chicago Tribune (Illinois), Mar 15, 1879

- The Sun (New York, New York), Apr 27, 1879

- The York Daily (Pennsylvania), Dec 29, 1879, Jan 2, 1880

- The Atchison Daily Champion (Kansas), May 17, 1885

- The Baltimore Sun (Maryland), Mar 21, 1879

- The Daily Gazette (Wilmington, Delaware), Mar 22, 1879

- The Cincinnati Enquirer (Ohio), Mar 22, 1879

- The Muscatine Journal, (Iowa), May 12, 1879

- Nebraska State Journal (Lincoln, Nebraska), Feb 17, 1881

- The Morning Post (London, England), Apr 22, 1879, Nov 2, 1880

- The Graphic (New York, New York), Jan 27, Mar 8, 1881

- The Buffalo Commercial (New York), Feb 4, 1882

- Buffalo Evening News (New York), Feb 27, 1882

- New York Tribune (New York), Feb 27, 1882

- The New York times (New York), Feb 28, 1882

- The Bismarck Tribune (North Dakota), May 9, 1884

- The Argentine Eagle (Kansas), Aug 26, 1892

- Abilene Weekly Reflector (Kansas), Jul 16, 1896

- Evening Star (Washington D.C.), Dec 26, 1896

- The Gazette (Montreal, Canada), Dec 28, 1896

- The Ottawa Journal (Ontario, Canada), Jul 19, 1897

- S. Marshall “Charlie Rowell – aka the Cambridge Wonder”

- P. S. Marshall, “George Hazael: The First Man to Run 600 Miles in 6 Days!”

- P. S. Marshall, King of the Peds

- Matthew Algeo, Pedestrianism: When Watching People Walk Was America’s Favorite Spectator Sport

- Andy Milroy, Long Distance Record Book

- Harry Hall, The Pedestriennes: America’s Forgotten Superstars