Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 32:13 — 40.1MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

In 1878, thanks to those in England, the 100-miler opened up to runners who could “go as you please” rather than sticking to a strict “heel-toe” walking style that was emphasized in America. That year, well over one hundred successful 100-mile finishes were accomplished with times that fell dramatically as the 100-mile athletes learned to trot.

Also that year, women especially left their mark on the 100-mile sport in America, as the country became fascinated with their accomplishments. The most prolific 100-milers in 1878 were women! It was written, “One of the most peculiar features of the walking mania is the number of lady pedestrians now on stage, and the surprising speed and powers of endurance which they exhibit.”

Mark Twain’s 100-miler

The two started on November 19, 1874 at 9 a.m. intending to stay on an old turnpike, see the hamlets along the way, and avoid walking on the railroads. After ten hours and 28 miles, they stopped for the night. “Before retiring, they had a consultation and decided that their undertaking had developed into anything but a pleasure trip and was actually hard work.” They decided to postpone their pedestrian tour for a year or so.

In the morning they walked seven more miles for a total of 35 miles, and then took the train to Boston. Twain said, “My knee was so stiff that it was like walking on stilts.” It was written, “Mark Twain wishes it to be distinctly understood that the walk was not a failure and they would have continued the trip had Mr. Twitchell not have been under engagement to preach in Newton on Sunday morning.” He said that next time he would reserve a week for the 100 miles but that he was not anxious to take away Edward Payson Weston’s laurels because he did consider that he was at least as good as Weston.

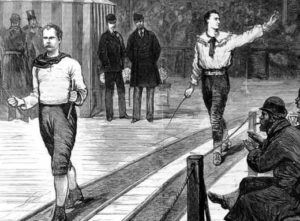

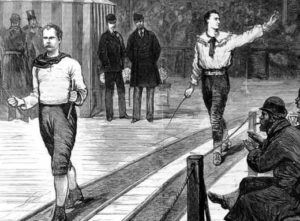

Daniel O’Leary

In 1874 O’Leary overheard a group discussing Weston’s attempts to walk 100 miles in twenty-four hours. One person said that only a Yankee could accomplish the feat. Another commented that Weston was planning on going to Europe. O’Leary said, “If he dropped into Ireland on the way he’d get beaten so bad that he’d never again call himself a walker.” Everyone laughed at him. He finally said that he thought he could beat Weston. They then roared with laughter.

O’Leary wanted to prove that an Irishman could be a successful distance walker too. He rented the West Side Rink on at the corner of Randolf and Ada Streets in Chicago, and announced that he would be attempting to walk 100 miles in 24 hours. For training, he accomplished 70 miles in one day on a rough road.

O’Leary’s first 100-mile attempts

![]()

![]()

A month later O’Leary tried again, this time to reach 105 miles in 24 hours for a wager of $1,000. The track to be walked was somewhat wet and slippery because of a leaky roof, but they threw down a little sawdust to make the walking good. O’Leary walked with an injury, a swollen hand, caused by being bitten recently by a pet monkey.

O’Leary challenged Weston to a 250-mile walking match but was brushed off by Weston who said, “Make a good record first and meet me after.”

Tit for Tat – O’Leary vs Weston

Weston noticed, and a couple weeks later in May 1875, he made an attempt in New York to reach 118 miles within 24 hours. He came up one mile short, reaching 117 miles, but reached 100 miles in 20:01:58 “without a rest.” He was pleased that he beat O’Leary 116 miles at Philadelphia.

Weston’s most famous achievement at that point was reaching 500 miles within six days. He had failed multiple times during 1874 to achieve that milestone but finally succeeded in December 1874 at Newark, New Jersey. O’Leary wanted to prove that he could do it too, but curiously gave himself six and a half days. He made his attempt at the West Side Rink in Chicago on May 15, 1875. He reached 100 miles in 23:01 and went on to reach 500 miles in 156 hours instead of 144 hours. He won $1,000 and was presented by his friends a medal engraved with “Champion Pedestrian of the World.”

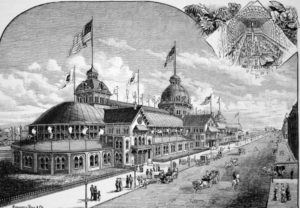

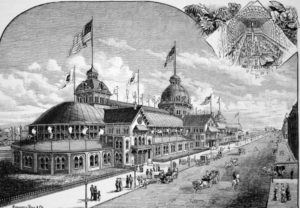

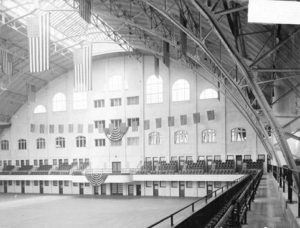

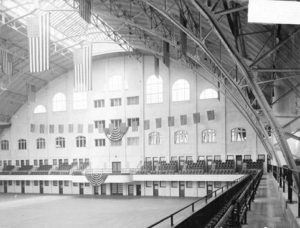

In November 1875, O’Leary and Weston finally competed head-to-head. It was a six-day walking match held at the Exposition Building in Chicago. The building was massive, the largest enclosed public meeting space in the United States at that time. O’Leary reached 100 miles in the lead at 20:48:21 and went on to defeat Weston by 51 miles, reaching 500 miles in 143:13, and finishing with 503 miles. Both became very rich men, dividing the $11,000 gate money evenly. That was worth a quarter million dollars in 2020 value.

Pedestrian Fever in Chicago

1875 100-mile races

During 1875, there were at least 20 successes by pedestrians in reaching 100 miles in 24 hours. Some of those achievements occurred in races. Nearly all of them were conducted indoors to charge spectators.

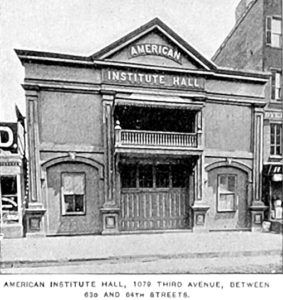

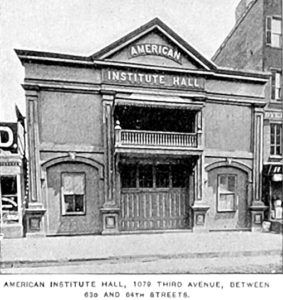

On April 10, 1875 O’Leary raced 100-miles at the American Institute Hall rink, located at the corner of 63rd street and 3rd Avenue in New York City. He competed against John DeWitt of New York and gave DeWitt and 10-mile head start. The purse for the event was $1,000. DeWitt gave up after 57 miles and O’Leary finished his 100 in 23:52:14

100-mile race busts

Many of the early 100-mile races were busts, with no one finishing. Often races were stopped once there was only one man left standing. In 1875, a 100-mile race was billed as the “championship of America.” It was held at the American Institute Hall in New York City. The competitors were George B. Coyle, the champion from Wisconsin, and William E. Harding of New York. “Great interest was manifested in the match.” Coyle was the favorite because Harding had never walked in a match of more than 50 miles.

The highly anticipated race was held on May 28, 1875 starting at 10:37 p.m. Both walked non-stop for about the first 35 miles, with Harding in the lead. It still was close when they reached 50 miles in about 11:30. “The exertion and fatigue were visible on both men, although Harding made an occasional spurt, which won the applause of the large audience present during most of the day.” But later during the morning, Coyle suffered terribly. “His limbs were chafed, felt sore, and a pain in the stomach and groin caused him intense agony.” He quit at mile 75. Instead of finishing the race, Harding was declared the winner, reaching 78 miles in about 24 hours.

Another 100-mile race was a bust in Mechanics’ Hall in Boston held May 3, 1875 between George F. Avery and Charles A. Cushing, both of Boston. Cushing reached 96 miles and Avery 84 with a cut-off time of 24 hours.

In December 1878 “The Great 100-mile Walking Match” was held in Belvidere, Illinois between Donahue and Cross at Union Hall. “It didn’t amount to much. They walked about 35 miles apiece and quit. The thing was also a failure financially.”

One Hundred mile races were often held outdoors on horse racing tracks. In Jun 1875, a 100-mile race billed as “the Championship of New England” was held outdoors at Mystic Park, a horse track in Boston, Massachusetts. The competitors were between an Englishman, John Haydock of New York, and Bostonians Avery, and Cushing. Haydock won in 23:36:29. Cushing dropped out at 71 miles, and Avery at mile 75. Haydock won $300.

Weston in England

24-hours against Perkins

For his first English race, Weston competed against William T. Perkins, “the champion pedestrian of England,” in a 24-hour competition at the Agricultural Hall in Islington, London, England on February 8, 1876. Perkins was “the wonder of the day among English walkers – The Champion, beyond all doubt at any distance up to fifty miles.” He was known as the only man who had ever walked eight miles within an hour.

Two tracks were measured out, with gravel and sand put down on boards. The outside track was six and a half to the mile and the inside, seven. Perkins chose to walk on the outside track. The official race program announced, “Nothing stronger than coffee will be sold at the bar, smoking is positively forbidden in the building, and hundreds of ladies belonging to England’s proudest nobility have already promised to be present.”

The race began at 9:25 p.m. Perkins immediately took the lead “going off with a capital stride.” The English press commented, “It at once became apparent that Perkins is far better than his opponent. Perkins’ style is simple perfect, with long rapid strikes, striking well out from the hips. He covers the ground at a tremendous pace and uses his arms in a way that seems to help him along. Weston, on the other hand, reminds one of a country farmer swinging along when trying to make up for lost time.”

They were allowed to reverse direction after any lap when reaching the judges box. Both took advantage of that option often, in order to avoid constantly working one leg. Perkins was the first to leave the track for some rest and refreshment after about six hours of constant walking, with a four-mile lead. He feasted on a mutton chop and drank a pint of Burton ale.

At 8 a.m. (10:35), Perkins was leading by a mile, with 54 miles, but appeared “much fatigued” and Weston soon took the lead. Weston never left the track until about mile 70. He then took his first rest of only one minute, 20 seconds.

Perkins quit after 65 miles because of bad blisters. His socks were saturated with blood and had to be cut off his swollen feet. The press still thought he was a hero. “Perkins though broke down, proved himself to be what all who know him have long thought of him – game to the backbone.”

Weston continued on alone and suffered through a period of vertigo and pain. He fueled on beef tea, beaten-up eggs, toast, jelly, grapes, prunes, coffee, tea, milk sugar and diluted brandy. As he neared 100 miles, he increased his pace “amidst the most enthusiastic cheers at his pluck and determination.” He hit 100 miles in 19:20 and reached 109 miles in 24 hours. He caught the attention of the British and published a challenge to any man in England. 100-mile walking during that era was not very widely competed at that time, but the Brits started to train furiously.

48-hours against Clark

Only a week later, Weston competed in a race against Alexander Clark, of Hackney, England. Clark was recognized at the time of having the fastest 50-mile time in England. The race was for 48-hours and held in the Agricultural Hall. Clark used the outside track and Weston was on the inside track. The race was close and very competitive. They were essentially tied at the 12-hour mark with 54 miles. But after 55 miles, Clark quit. Weston continued alone, reached 100 miles in 23:30:35 and then showed off by walking the next lap backwards. He went on to reach 180 miles in 48 hours, finishing in front of a “wildly excited” crowd of 5,000 people. He gave a speech and then blew on a cornet the tune for “God Save the Queen.”

Weston’s dominance in England

Despite Weston’s early dominance in England, it was written, “Nothing is more common than to hear opinions expressed to the effect that the recent performances of Mr. Edward Payson Weston, however marvelous they may be, are of no practical utility.”

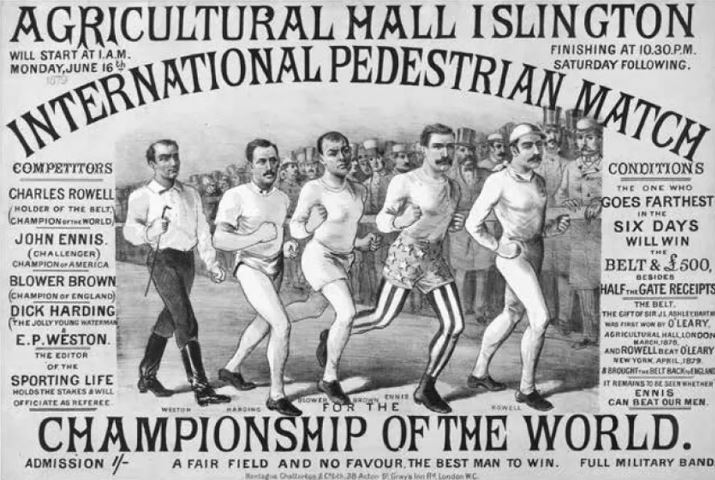

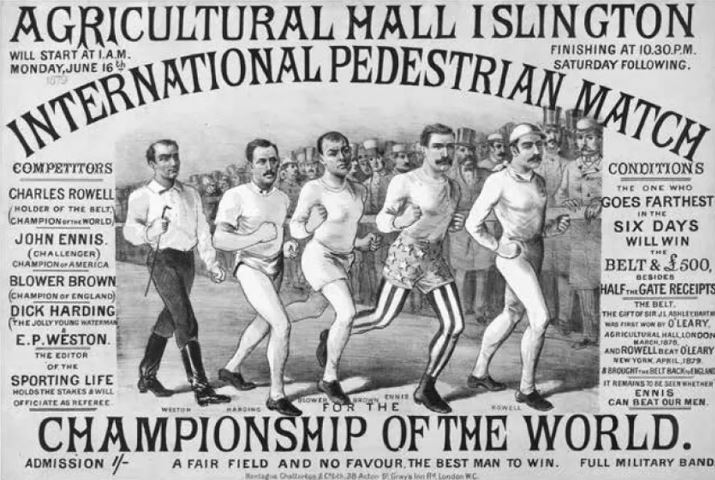

A week later Weston competed for 75 hours. His competition, Charles Rowell, was allowed to run or walk as he pleased, and was spotted 50 miles by Weston. Rowell quit after 176 miles and Weston reached 275.

Weston continued to compete in England in many distances greater than 100 miles. By May, the competition became greater as several Brits were able to walk sub-19-hour 100-milers in Agricultural Hall in larger races. O’Leary joined in competing internationally when he also went to England in 1877 beating Weston again in a head-to-head six-day race.

100 milers in America

100-mile accomplishments continued back in America including the first known walker from California when Robert Allen reached the milestone in 24 hours at San Jose in September, 1876.

O’Leary vs Ennis

The Chicago Times wrote, “Ever since Dan O’Leary began his career as a pedestrian he has been fighting down men who believed that because they were of his city of Chicago, that they were as good as he. The most promising of these men had been John Ennis, who had been a prominent athlete.”

On November 10, 1877, O’Leary and Ennis faced off again in a 100-mile race. It was held at the Exposition Building in Chicago for $500. There were hopes that one of the athletes would break 19 hours.

A large crowd of spectators cheered the start but very soon afterward, Ennis was attacked with a violent pain in his bowels and for some time it was feared that he would have to quit very early. But he continued on, using spurts of speed. By mile 46, O’Leary already had a 15-mile lead and Ennis was still suffering. “At the end O’Leary was fresh as a daisy, while Ennis was pumped out, done-for, busted, ruined, and gone. Ennis only reached 54 miles. Despite the lack of competition, O’Leary went on and finished 100 miles in 19:59:40.

Go and You Please

Pedestrian historian, P. S. Marshall explained, “Competitors would be able to ‘walk, trot, run, mix, lift or introduce a new style of pedestrianism if clever enough.’ This was a decision made for two reasons, one of which was apparently because of Weston’s ‘wobbling gait’ which was considered as not being textbook heel-and-toe, and the other was because there was a view that because the American athletes were so much better at walking than their British counterparts, a method of progression was needed to be invented to disadvantage the best of those athletes.” Dan O’Leary won the First Astley Belt, held in the Agricultural Hall, reaching 520 miles, beating 17 other competitors.

100-mile records broken

As more British long-distance runners extended their endurance to ultra-distances, they began to truly excel at distances of 100-miles and greater. The Agricultural Hall in London was the ultrarunning venue for the world in 1878. As “go as you please” rules were adopted, speed increased as the athletes learned how to incorporate trotting along with their walking. Several British runners started to reduce their 100-mile times close to 18 hours. It was a landmark year. The era of the 100-mile runner began, allowing runners with long-distance skill to enter the sport of pedestrianism/ultrarunning.

The long-standing 1824 100-mile record of 17:52 set by Edward Rayner of England was then 54 years old. No one else had reached 100 miles in less than 18 hours, not until 1878.

A “Long Distance Championship of England” was held at the end of October 1878 in the Agricultural Hall in the form of a six-day race. The track provided was ten-feet wide covered with dirt. Comfortably furnished tents were provided for each runner on the north east side of the building near a bathroom reserved for their use. Compared to past races held there, the accommodations were considered luxurious. There were 23 runners. About 10,000 spectators were on hand when Henry “Blower” Brown of Fulham, England broke the 18-hour barrier reaching 100-miles in 17:54:05. Eight runners that day reached 100 miles in less than 24 hours.

Hazael was described as having “a bulldog face, short cropped hair and almost deformed stooped shoulders which gave him the most displeasing appearance. At the start, Hazael shot of into the lead and kept increasing his lead during the day. He surprised everyone when he broke the 100-mile world record with a time of 17:04:06 and went on to win the six-day race. (Several years later, in 1882, Hazael became the first man ever to reach 600 miles in six days.)

The 100-mile Women Pedestriennes

Following in the footsteps of Madame Moore of 1869, more women started to compete in 100-milers in the late 1870s. Walking among women started to take hold in England. It was observed, “The English girls are great walkers, and they diverge from the state roads and make excursions among the mountains.” But at the same time, there was concern about American women. “American girls are generally poor walkers, and it will soon be a difficulty to find an American lady who can walk more than twenty minutes without complaining of fatigue. They pay too much attention to the shape and make of their boots for pedestrian performances.” But all that would change quickly as American women took center stage among American pedestrians during the late 1870s.

In 1879 it was written, “One of the most peculiar features of the walking mania is the number of lady pedestrians now on stage, and the surprising speed and powers of endurance which they exhibit. Although it has long been known as a singular fact that a girl who was too delicate to bring a pail of water from the well to the kitchen could dance half a dozen vigorous men, it was not until recent women made their wonderful walks , that the powers of lady walkists began to be appreciated.”

Bertha Von Hillern

She walked in several matches in Berlin and other European cities in her teens. In 1875 she emigrated to America at the age of 18 to start a new life, even though she did not speak English well. She made her way to Illinois, continued walking and advocated athletic exercise for women.

The male press made this description, “Miss Von Hillern is 20 years of age, five feet and three inches in height, and weighs 110 pounds. Her hair is of light flaxen tint, her features somewhat irregular but pleasant, and her figure is trim. In the opening of the present contest she wears a tasteful purple dress, with short skirts, and polonaise trimmed with lace.”

The track they walked on was four feet wide and laid out as big as possible for the hall the race was held in. But the loop was tiny, with twenty-two laps to the mile. Soil and sawdust were laid down about three inches thick. Sleeping rooms were provided for them on the second floor by a long flight of stairs. Muscular female attendants rubbed them down with a liniment when they became stiff. Two solid meals were provided for them each day including beef and mutton. While walking they would drink strong beef tea and eat oatmeal with milk. Von Hillern won the race, reaching an amazing 323 miles.

It was reported, “Her success is regarded as a surprising demonstration of the possibilities of women’s endurance. It contains a valuable lesson to our girls of the benefits of pedestrian exercise to health.”

A month later she walked 350 miles in six days at a Music Hall in Boston, Massachusetts, making 7,000 circuits around the track. Her walking time, not including rests, was 92 hours. “Towards the last, the wonderful exhibition in the Music Hall became the sensation of the town and drew large Bostonian audiences. If its effect shall be to encourage in the women of Boston the practice of walking more, the natural result of rosy cheeks, bright eyes and increased physical strength will surely follow.” Her 350-mile shoes were put on display at “Tuttles shoe store” and was “attracting considerable attention.” She became the darling of Boston, hero among German-Americans, and was very famous across the country, recognized as the woman pedestrian champion.

Von Hillern was also a 100-mile walker. She trained hard for her first 100-miler, walking four hours per day and one hour of gymnasium exercise per day. She put on many 100-mile exhibitions, performing them between 27-28 hours. At Worcester, Massachusetts it was remarked, “the now large crowd followed her very motion with eager eyes, the patter of ladies’ hands and fans, and the waving of handkerchiefs preceding and following her like a wave around the hall.” Von Hillern was the most prolific 100-miler among men or women during 1877-78, achieving that distances at least 12 times during a one-year period.

Von Hillern also made an impact on women’s shoes, introducing “zero-drop” styles. A Kansas newspaper commented, “The female pedestrian of Washington, Bertha Von Hillern, walked 100 miles in 28 hours. She wears long, broad-soled shoes with low-heels, or without heels, and all the ladies of that wicked place are adopting her kind of shoe. Are there any “Berthas” in Kansas?”

May Marshall

She was 25 years old and from Chicago and Dan O’Leary assisted in her early training. After competing with Von Hillern in the 1875 six-day matches, Marshall also started to complete 100-mile walks. Her first attempt was at the Music Hall in Boston, Massachusetts during March 1877. She “started off with a fine burst of speed” at 8 p.m. She experienced many issues along the way but preserved with “almost inflexible will power which called forth universal admiration.” After 21 miles, she started taking frequent rests. At mile 83 her feet were so sore and swollen that she tossed away her shoes and walked the rest of the way in stockings. “The enthusiasm during her last mile was intense, the vast number of spectators present cheering her at the top of their voices, and waving their hats and handkerchiefs as she put in two extra laps.” Her time was 26:47, much faster than Von Hillern’s best.

Marshall tried again in July at New Bedford, Massachusetts where she suffered terrible. “At times she would hold both hands above her head as if in extreme agony, and many ladies in the audience shed tears of pity. The committee begged her to stop, but when it was announced that she meant to continue, the large audience applauded enthusiastically, spurring on the fainting woman, who could hardly stand alone, and was almost carried around the track by men who held her up and hurried her on while they fanned her. The band played ‘The Girl I Left Behind Me.’”

Marshall stopped competing in 1877 because she was with child. She returned for a brief time in July 1878 and continued for several years to perform various publicity stunts, including races against skaters and people pushing wheelbarrows.

Kate Lawrence

Kate Lawrence, age 30, was a dress-maker from San Francisco, California. She took up long-distance walking in 1877, believing that she could walk 100 miles faster than Bertha Von Hillern. She did serious training during 1877 to ease up her walking miles. Her first exhibition was at the San Francisco Horticulture Hall where she reached 75 miles in 24 hours. “Mrs. Lawrence has walked daily to and from the city to the Cliff House, doing the sixteen miles in three hours for months before breakfast, and then doing her regular day’s work.”

Her first 100-mile attempt occurred in September 1877, in Pacific Hall in San Francisco. She finished in 27:40 about the same pace normally accomplished by Von Hillern. She repeated that journey in March 1878 at a Pavillion in Sacramento, improving her time to 27:36:30. “It is the intention of Miss Lawrence to travel East and throw down the gauntlet, or rather the slipper, after demonstrating her pedestrian powers in San Francisco.” In July 1878, at Woodland, California she finished 100 miles in 26 hours.

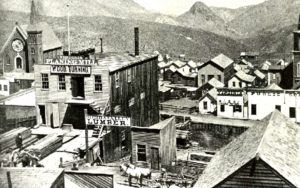

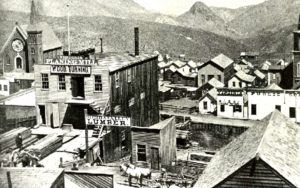

In August 1878, Lawrence was getting ready for her next 100-miler to be held at Virginia City, Nevada. A reporter was eating dinner in a restaurant when Lawrence came. She asked for a private room and a square meal. He said she came in “with the frightened air of one avoiding the police.” She whispered her order to the waiter for a big thick steak, biscuits and coffee. “In a few minutes the order was filled, and the woman began to eat as if she had not tasted food for twenty-four hours. Between every mouthful, she cast furtive glances at the door, seemingly constantly expecting someone.” Soon a short man entered, searched the restaurant and found Lawrence. He glared at her and took away her food. The man was her trainer, Tom Kean. She had been on a pre-race starvation diet prior to her 100-miler the next day. Kean was furious and screamed expletives. “Hell’s Bells, this is the worst yet!” Then he took her by the arm and led her away “like a husband who was conveying home an erring wife.” After that exchange, evidently Lawrence fired him.

The next day Lawrence walked her 100-miler at Virginia City, Nevada. During that walk, her former agent tried to stop her walking by presenting a bond for an alleged debt. Spectators paid the bond and the walk went on. “A large audience witness the close of the walk, and the excitement was intense.”

M’lle Dupree

M’lle Dupree, a French-American seamstress from Sparta, Wisconsin, started walking 100 miles in 1878. She was a mother and would at times walk miles with her eight-year-old daughter, Minnie. In May of that year, she made her 100-mile debut in Buffalo, New York, finishing in 26:45. But people were even more impressed that Minnie walked five miles in 1:04:30. About a month later, Dupree improved her 100-mile time to 24:50 at Stillwater, Minnesota. She next set her goal to break 24-hours, a seemingly barrier.

Earlier, in 1877 Carrie Parker, a woman from Illinois, accomplished a 24-hour 100-miler. People believed it ruined her life and drove her to insanity. She was “a raving maniac” when she was brought before a court. “Her father testified that ever since the walking match his daughter had been suffering with great nervous prostration and recently she suddenly conceived of the idea that her whole body was charged with electricity and she would not touch her feet to the floor.” She was sent to an asylum.

Was a sub-24-hour 100-miler too tough on women?

Dupree made her first attempt to walk 100 miles in under 24 hours, in July 1878, at Association Hall in La Crosse, Wisconsin. A course laid with sawdust was constructed in the spacious hall, with 17 circuits per mile.

“At 9 o’clock p.m. Madame Dupree made here appearance dressed in white tights with a short over-dress reaching just below the loins, and a bodice without sleeves. She is a woman above the medium height, probably thirty-five years of age, well developed, but without superfluous flesh, and with sharp firm set, but not attractive face.”

She walked with ease with full swinging steps and reached 25 miles in 5:42. During the night she was paced by some amateurs but her ten-minute-mile pace was too fast for them. She reached 50 miles in 11:49. “She was less flushed and there were signs of paleness. She changed her costume, appearing in a ballet dress.” She reached 100 km at 18:50. In the end, she reached 91 miles in 24-hours and withdrew at the advice of a doctor. Her shoes seemed to be the biggest problem, leaving her feet swollen and blistered.

Dupree was still determined to try again and was finally successful at Mankato, Minnesota with a time of 23:05 in September 1878. The next month in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, she walked 110 miles in 25 hours. During the walks, little Minnie would do impressions of Dan O’Leary, delighting the crowds. Her son Frank walked one mile in six minutes. Indeed, she put on entertaining events, walking 100 miles about every month for a while. She was the fastest woman 100-miler up to that time and started to be referred to as “The wonder of the world.”

Exilda LaChapelle

In May 1878, she again walked 100 miles, this time in Janesville, Wisconsin with an outstanding time of 25:48. “The mayor, having heard that she had been compelled by her husband to walk against her will, tried to call her off the track, but she said, ‘nobody could compel me to walk or to stop.’ Plucky little woman!”

American 100-mile record

1878 concluded with a spectacular 100-mile performance by James Smith at the Opera House in South Bend, Indiana. The track was extremely tiny, 30 laps per mile, 176 feet per lap, or 3,000 laps for 100 miles. It was a very dizzy 100-mile challenge, with 12,000 turns, that required a very intent time-keeper. Smith fueled on 20 pounds of beef-steak and drank coffee and tea. “Up to the 50th mile (at 8:41:45), the pedestrian showed no signs of fatigue, but after he had passed that, his right ankle began to grow lame from the frequent turning of corners and he slackened his speed somewhat. Many spectators came to watch and in the evening the house was full. Toward the end the reaction of the crowd was intense. “

Smith reached 68 miles in 12 hours. “As the timekeeper announced the laps on the last mile, each one was received with applause, and the walker acknowledged it by a spurt which proved that he was not entirely exhausted. As the 30th lap of the 100th mile was announced, Smith was not content but spun around the track at a frightful speed and the audience could not cheer enough.” He finished with a time of 18:26:30. He finished with a time of 18:26:30 and had broken the American best by 22 minutes.

1878 has been a banner year during the 100-mile craze, with well more than 100 finishes in America and England, including at least 22 100-mile finishes among the women. About a century would need to pass until there were more 100-mile finishes in a calendar year.

The parts of this 100-mile series:

- 54: Part 1 (1737-1875) Edward Payson Weston

- 55: Part 2 (1874-1878) Women Pedestrians

- 56: Part 3 (1879-1899) 100 Miles Craze

- 57: Part 4 (1900-1919) 100-Mile Records Fall

- 58: Part 5 (1902-1926) London to Brighton and Back

- 59: Part 6 (1927-1934) Arthur Newton

- 60: Part 7 (1930-1950) 100-Milers During the War

- 61: Part 8 (1950-1960) Wally Hayward and Ron Hopcroft

- 62: Part 9 (1961-1968) First Death Valley 100s

- 63: Part 10 (1968-1968) 1969 Walton-on-Thames 100

- 64: Part 11 (1970-1971) Women run 100-milers

- 65: Part 12 (1971-1973) Ron Bentley and Ted Corbitt

- 66: Part 13 (1974-1975) Gordy Ainsleigh

- 67: Part 14 (1975-1976) Cavin Woodward and Tom Osler

- 68: Part 15 (1975-1976) Andy West

- 69: Part 16 (1976-1977) Max Telford and Alan Jones

- 70: Part 17 (1973-1978) Badwater Roots

- 71: Part 18 (1977) Western States 100

- 72: Part 19 (1977) Don Ritchie World Record

- 73: Part 20 (1978-1979) The Unisphere 100

- 74: Part 21 (1978) Ed Dodd and Don Choi

- 75: Part 22 (1978) Fort Mead 100

- 76: Part 23 (1983) The 24-Hour Two-Man Relay

- 77: Part 24 (1978-1979) Alan Price – Ultrawalker

- 79: Part 25 (1978-1984) Early Hawaii 100-milers

- 81: Part 26 (1978) The 1978 Western States 100

- 87: Part 27 (1979) The Old Dominion 100

Sources

- The Philadelphia Inquirer (Pennsylvania), Sept 2, 1868

- Mark Twain’s Letters, Volume 6: 1874-1875

- Chicago Tribune (Illinois), Jul 14, Aug 22-23, Oct 8, 1874, May 30, 1875, Oct 17, 1875, Dec 24, 1876

- The Findlay Jeffersonian (Ohio), November 27, 1874

- The South Bend Tribune (Indiana), Apr 12, 1875

- The St. Albans Advertiser (Vermont), May 21, 1875

- Intelligencer Journal (Lancaster, Pennsylvania), May 18, 1875

- The Philadelphia Inquirer (Pennsylvania), May 31, 1875

- The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (New York), Jun 21, 1875

- Boston Post (Massachusetts), May 24, 1875

- Time Union (Brooklyn, New York), Aug 14, 1875

- The St. Albans Advertiser (Vermont), May 21, 1875

- Harrisburg Telegraph (Pennsylvania), Oct 23, 1875

- The Indianapolis News (Indiana), May 3, 1875

- Lebanon Daily News (Pennsylvania), May 4, 1875

- The Age (Melbourne, Australia), Jul 20, 1875

- The Topeka Weekly Times (Kansas), Dec 10, 1875

- Northern Echo (Dalington, Durham, England), Feb 17, 1876

- Daily News (London, England), Feb 18, 1876

- Reynold’s Newspaper (London, England), Feb 13, 26-27 1876

- The Era (London, England), Feb 6, 1876

- The Nottinghamshire Guardian (England), Feb 11, 1876

- The Huddersfield Chronicle (England), Feb 28, 1876

- The Star (Saint Peter Port, England), May 3, 1877

- The Inter Ocean (Chicago, Illinois), Nov 6, 1877

- The Leavenworth Press (Kansas), Nov 10, 1877

- The Buffalo Sunday Morning News (New York), Nov 11, 1877

- The Ottawa Free Trader (Illinois), Jun 23, 1877

- The Standard (London, England), Oct 29, 1878

- P. S. Marshall, “George Hazael: The First Man to Run 600 Miles in 6 Days!”

- P. S. Marshall, King of the Peds

- Matthew Algeo, Pedestrianism: When Watching People Walk Was America’s Favorite Spectator Sport

- Andy Milroy, Long Distance Record Book

- Harry Hall, The Pedestriennes: America’s Forgotten Superstars

- The Morning Post (London, England), Mar 7, 1876

- The Times-Democrat (New Orleans, Louisiana), Dec 26, 1875

- The Daily Milwaukee News (Wisconsin), Feb 6, 1876

- Pittsburgh Daily Post (Pennsylvania), Feb 7, 1876

- The Boston Globe (Boston, Massachusetts), Oct 27, Dec 25, 1876, Feb 10, 28, 1877

- The Columbus Republican (Indiana), Nov 9, 1876

- Vermont Journal (Windsor, Vermont), Dec 2, 1876

- Kansas Weekly Herald (Hiawatha, Kansas), Feb 14, 1878

- The Intelligencer (Anderson, South Carolina), Sep 13, 1877

- North Wales Chronicle (Bangor, Wales), Dec 1, 1877

- The York Dispatch (York, Pennsylvania), Aug 15, 1877

- The Rock Island Argus (Illinois), Jun 2, 1877

- The Burlington Free Press (Burlington, Vermont), Aug 24, 1877

- The Saint Paul Globe (Minnesota), Sep 5, 1878

- The Star Tribune (Minneapolis, Minnesota), Jul 1, 3, 5, 22 1878

- The Daily Milwaukee News (Wisconsin), Jul 14, 1878

- Des Moines Register (Iowa), Oct 30, Nov 13, 1878

- Kansas Daily Tribune (Lawrence, Kansas), Feb 8, 1879

- Fitchburg Sentinel (Massachusetts), Mar 7, 1877

- The Sacramento Bee (California), Jul 6, 1878

- The San Francisco Examiner (California), Aug 5, 1878

- Los Angeles Herald (California), Aug 21, 1878

- The South Bend Tribune (Indiana), Dec 21,23, 1878

- The Cincinnati Daily Star (Ohio), May 30, 1878

- Buffalo Weekly Courier (New York), Sep 11, 1878

- The Belvidere Standard (Illinois), Dec 17, 1878

- Email from May Marshall’s great-great-grandson on July 13, 2021