Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 29:35 — 38.8MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

In America, 100-mile races were being held, open to anyone who wanted to give it a try, even the naïve. In 1975, the annual Camellia 100 held in the Sacramento, California area was held for the fifth year.

But the oldest annual American 100-miler that tends to be forgotten, was the Columbia 100 Mile Walk held in Columbia, Missouri. In 1975 It was held for the ninth year. There had been 23 sub-24-hour 100-miler finishes in its history. But this was nothing compared to Great Britain. There, 100-mile walking races had been held annually since 1946, for 30 years, with more than 450 finishes in less than 24 hours.

Elsewhere, the Durban 100 held every-other year in South Africa, had been competed six times, with at least 33 finishers (only partial results have been preserved). In Italy, 24-hour races had been held every year since 1970 with 100-mile finishers. In 1975, a 24-hour race with many 100-mile finishers was competed inside the Soviet controlled iron curtain, in Czechoslovakia.

|

The Greatest 100-miler – Acolade 100

The 100-miler was an invitation-only race and 18 competitors were carefully selected out of a large group who were interested. All were very experienced ultrarunners, but only a few had actually finished a 100-miler. The most experienced 100-miler runner was Ron Bentley, the current 24-hour world-record holder of 161 miles (see episode 65). But Bentley was hampered by a recent groin injury. The race was held just three weeks after the major ultramarathon of the time, London to Brighton (52 miles). This was a concern because some of the runners also ran there, but they held to the scheduled date.

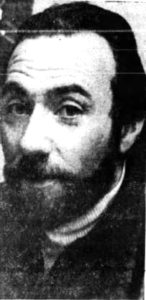

Cavin Woodward

He took up marathon running in 1971 because he “felt sorry” for Leamington’s veteran marathoner, Tom Buckingham (1918-1976), age 53, who seemed like he always was the only club member competing in marathon events. Buckingham had started running in 1946. Woodward said, “Tom never seemed to have any support so I decided to run with him. Other distance runners then joined the club.” Soon several runners in the club started to compete in London to Brighton (52 miles).

In September Woodward ran again at London to Brighton. From the start, he went out fast, grabbed the lead running 10 miles in just 55 minutes. He explained, “I felt that if I wanted to win the event, I would have to be three minutes ahead of the opposition after 30 miles. In fact, I was four minutes up on them. But even at that stage I couldn’t relax. There were 24 South Africans in the field of 100 and I didn’t know what they were capable of doing. I always start fast, but for all I knew they could have been strong finishers.” He won, finishing only a minute off the course record. He had finished on the podium for this international race four years in a row. There was no doubt that he was the most dominant ultrarunner in the world in 1975. Since 1972 he had finished on the podium of 16 or 17 races. By 1975 he had finished 26 marathons and 19 ultras.

Runner Martin Thompson wrote of Woodward, “He is 28 years of age, about 5 ft. 8 in height and weighs 130 pounds, enjoys his running, training twice a day, 3 miles in the morning and 10 miles in the afternoon with the pace varying between 6 and 7 minutes a mile. He is a prolific racer with rarely a weekend away from competing: cross-country, road, track and a few cycling races thrown in when light on for running races.”

Quest for the 100-mile Record

The 100-mile world record was 11:56:56, held by Derek Key of South Africa (see episode 65). Woodward knew that, and while planning for the race, examined Kay’s splits from his record-setting run. He decided that he would stick with his own strategy of going out fast as long as he could. He said, “No matter what pace you start at, you will slow eventually, so start at a fast pace which will give you momentum. The reason why I go out in front is because I want to run my own race. If you are in a bunch, and the front runners stop, you have to chop your stride. In front I can speed up when I feel like it, slow down when I come to a hill, judge the traffic, and do what I want to do.”

But Woodward had never run beyond 52 miles and had his doubts whether he could even “hang on” and reach 100 miles. He set his sights on a pace to break the world record but also planned a backup pace chart. He carbo-loaded before the race eating kippers, grapefruit, potatoes and sandwiches.

The Start

Runner Martin Thomas recalled, “The organization was superb with times called and recorded for every lap (400) for all competitors. As the day progressed the spectators grew in number and in the final stages the encouragement from the crowd was terrific. Dr. John Brotherhood of the Medical Research Council had a tent set up on the infield for testing urine samples and generally kept a check on all the runners.”

Woodward continue to cruise way ahead of the field and reached 50 miles in a world record time of 4:58:53, the first ever to break the five-hour barrier. He overheard someone remark, “He will now drop out somewhere in the race, so who will break the 100 mile record?” That bugged him. He continued on strong but did relax a bit. With a 34-minute lead over the next runner, he knew that he could break the 100-mile world record running the second 50 miles in a pace two hours slower that the first half. At mile 53, he made his first bathroom break.

A reporter wrote about what he witnessed, “Never will I forget the sight of Woodward responding to the urging, not only of his own supporters, but to the wholehearted backing of the spectators. Head lolling to one side for mile after mile. He carried the crowd with him. For me this was a new and wonderful kind of sportsmanship. Runners spurring each other on in spite of knowing that the man they were trying to help might finish in front of them. The spirit filled the reception area as runner after runner staggered toward the finish”

The Finish

After finishing, Woodward was overcome with emotion and had “a bit of a sob.” He was hustled from the track to an ambulance. He explained, “I was OK, they just wanted to get me away from the well-wishers and let me rest.”

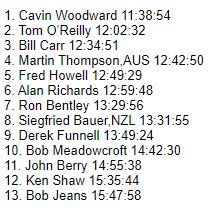

What made this 100-mile race so great, was that eleven runners finished in less than 15 hours. Woodward, looking back on the accomplishment said, “I proved that it could be done. I hope I have altered the outlook of some runners. I hope I proved that running even-paced is not the only way of winning races and breaking records. I would like to think that if a runner wants to try and run ultras fast right from the start against the wishes of his coach or trainer, he could convincingly argue that that was the way Cavin Woodward did it.”

Woodward finished without any significant injury, but said from home the next day, “I’m very stiff and aching all over. But considering I had never run further than 53 miles before, I feel great.” He recovered fast and ran with his club in races the following weekend.

Woodward was immediately given an invitation to run the Comrades Marathon the following year. He did and finished in 2nd place. For 1975 he received 4th place in a vote for Britain’s “Athlete of the Year.” Woodward continued to run ultras at a world-class level into his 50s until 1998. He ran more than 200 marathons or longer during his life and accumulated a collection of 600 trophies and medals. He died suddenly of a heart attack in 2010 at the age of 63.

1975 24 Hours at Dobrisi, Czechoslovakia

In 1968, the Soviet Union invaded Czechoslovakia. Prior to that, marathon runners had been participating in running events in western Europe. Ivo Domansky, a marathoner, who became a ultarunner, shared what life was like for an ultrarunner during the early 1970’s. “Around the end of 1971, normalization in the then Czechoslovak Socialist Republic came to close, and as for trips to capitalist foreign countries, it became increasingly difficult to travel there. I was less than 34 years old and I knew it would never be better in terms of running performance, and I started to care a little more about things other than walking and running.”

In 1973, Domansky managed to get the approval of the Tourism Association to go and compete in one of the several 100 km races that were beginning to be held in Europe. He went to run in the Copenhagen 100 km in Denmark, a road race in its second year.

Also with him was Bretislav Molata, who would be one of the greatest Czech ultrarunners of the time. For both of them, this was their first 100 km. In Copenhagen, they stayed in a large sports hall with sleeping bags. Their Sports organization under Communist rule had given them some money (only about $80 in 2020 value) for meals and pocket money but it was not much for their two-week trip, and they struggled.

At the start, about 600 runners took off in Copenhagen, going along the coast and running through Kronborg Castle, the setting for Shakespeare’s Hamlet. Domansky recalled, “To this day, I see in my mind a wreath of lights, on the opposite Swedish bank on the Strait of Oresund. We ran most of the 100 km at night.” Molata finished in 2nd place with 8:45 and Domansky finished in 6th with 9:28, a great showing against the Danes. About half of the field finished in more than 15 hours.

A couple year later they were also able to run in a 100 km at Biel, Switzerland with 2,500 runners and walkers. Many of these European 100 kms were both hikes and runs that would attract hundreds and even more than 1,000 walkers. These long-distance walkers were called “tourists.” This race had been held since 1959. Domansky finished 8th in 8:03. “It had a completely different atmosphere than Copenhagen. On Friday at 10 p.m., about 2,500 runners and tourists gathered at the start. The 100 km course in Biel was a large circuit without elevation gain, especially the difficult night section along the banks of the Aara River, which the local marathoners nicknamed the Ho Chi Minh Trail.”

Ultramarathons started to be held in Czechoslovakia in 1974, including a 50 km on a cross-country ski course in the Jizera Mountains and a 100 km road race held in Liberec.

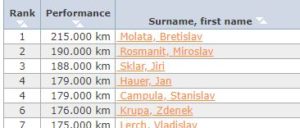

But the big event was held on September 19, 1975. It was a 24-hour race held at Dobrisi, Czechoslovakia. The road course consisted of a 100 km loop along with a one km out and back. There were 56 runners, including four women. The best ultrarunners in Czechoslovakia and others from a few other eastern European countries competed.

Tom Osler

Osler was an excellent student, but purposely lowered his grades for a while in order to fit in as a “regular guy.” Then the gang in his neighborhood picked distance running as “that day’s form of athletic torture.” Osler jumped in head-first and started to run. When he was fourteen years old, he had dreams that he would be the first person to break the four-minute mile. He said, “When you are young, you have dreams that seem very attainable.” He did a test mile run and finished in 6:30.

College Years

In 1957, Osler went to Drexel Institute of Technology in Philadelphia where he studied physics and won many academic awards. Osler loved running and found time during his busy college life to also be deeply involved with road running. In 1959 he helped found the Road Runners Club of America and was its first co-secretary. He raced multiple times a month in many shorter races put on by Browning Ross (1924-1998) in Philadelphia and throughout New Jersey.

Osler said, “At the time you only ran in a proper athletic setting. You ran in a park or on a track. You certainly never ran on the streets. If you did, you were stared at by everyone.” Yes, he ran on the roads. “Other runners would ask me, ‘how do you stand the ridicule?’ My answer was that I simply ignored it.” Frequently he was stopped and questioned by police while running, thinking he was running to try to get away after doing some crime. Once he was even pulled into a patrol car. Osler said, “He popped out of his car like a jack-in-the box and tackled me. Before I knew what was happening, I was in the car beside him.” For his first six years of serious running, he raced at every opportunity. In a field of about 50 runners he would finish about 15th to 20th.

But over training started to plague him. He said, “I had a sciatic nerve condition that left me unable to walk. I still remember going out to train and going so slowly due to hip pain that even the dogs looked at me puzzled. They couldn’t decide if I was running or not and were confused as to whether to chase me.” He soon figured out that rest and healing was just as important as training.

After graduating from Drexel, Osler won a fellowship to graduate school at the Courant Institute of Mathematics at New York University where he received his PhD.

Becoming an Elite Runner

Osler became life-long friends with future ultrarunning legend, Ed Dodd, in the early 1960’s when Dodd was still in high school. They would do long training runs together. In 1965 at the age of 25, Osler was “beaten soundly” by Dodd, age 19, who became captain of St. Joseph University cross-country team. This increased Osler’s motivation and “the old competitive zeal was put into high gear.”

In 1966 Osler became a math instructor at St. Joseph’s University in Philadelphia and continued his prolific racing and winning. In 1967 he set his marathon personal best at Boston, finishing 16th with a time of 2:29:04 That year he also won the National 30 km Championship.

Ultrarunning

In 1967 Osler was inspired by Ted Corbitt to give ultramarathons a try. With running buddies, Neil Weygandt and Ed Dodd, he began doing 50-mile training runs from Collingwood to Atlantic City, New Jersey. On August 13, 1967 Osler won a club 40-mile fun-run in Egg Harbor, New Jersey. Confident that he could do well, he began preparing to run in the 50-mile national championship to be held in November 1967. He worked up his runs to 55 miles. He ran every afternoon after classes covering 75 to 80 miles a week and averaged 7.5 minutes per mile.

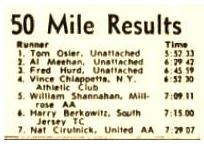

The first modern-era American 50-mile championship was part of the YMCA Thanksgiving Day Road Race, held in Poughkeepsie, New York. There were 13 starters, including legendary and future 100-mile world record holder, John Tarrant, “the ghost runner,” who came from England to run. (see episode 63)

Osler, the Author

Glassboro 24-hour Run

![]()

![]()

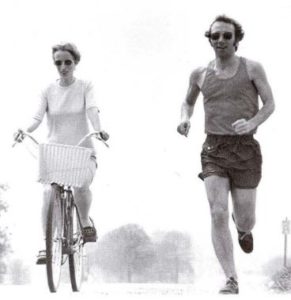

Osler did not sleep at all the night before. He couldn’t wait to get on the track. He started at 5 a.m. on the cold, clear December morning. It was about 20 degrees. He wore a hat, gloves and “ski pajamas” to cover his legs. Several friends started with him and ran portions of the distance through the day, including the college president.

He said, “Gradually, the light of dawn spread over the cinder track. I had thought before the run of the great beauty of watching the sun rise and set, and the night close in darkly while the run went ever on. I did my best to relax and stay fresh.” He reversed direction on the track about every half hour. During the day the track thawed and became wet and mushy.

Osler reached 50 miles in 8:08:13 feeling good. The sun set at the 70-mile mark. The freezing ruts in the track became a problem. Many students arrived to run with him. He recalled, “At 80 miles, I began to grow weary. For the first time, I was no longer comfortable. I really wanted to stop and take a rest but I thought it unwise.” He recovered at 95 miles and finished strong, reaching 100 miles in 18:19:27. The college president and reporters were there to offer congratulations.

“He stopped for a rest and a warm spaghetti dinner and a ten-minute nap. After the break, he couldn’t get himself to run at all and proceeded to walk for the remaining time, covering 114 miles before he was done.” He ended up running 90 miles and walking 24 miles. He was delighted to discover that his post-race recovery produced no leg stiffness. He said, “I really don’t feel too bad.” Ted Corbitt told him that it was because of his frequent walks. Osler said, “I now knew how the great pedestrians of the past century had achieved seemingly impossible mileage.”

Later Life

24-hour World Record Attempt – Sort of

“After two hours a white, unmarked car rolled past him near Brownsburg. A voice over the public address system on the car warned him to get off the highway. Dannettelle said he kept running but the car came by a second time and the voice said if he was seen again he would go to jail.” Dannettelle took the warning seriously, stopped his run and called for a ride. He later called the police but they checked their records and had no units in the area at that time. They said next time they would give him written authorization to carry. “We might as well help him since he’s a Hoosier. We are not the bag guys.”

Breaking a true world record was harder than it sounded. He vowed, “I’m going out again as soon as my leg heals and I’m going to break the record. There’s no doubt in my mind I would have broken the record.” a few weeks later, he may have quietly tried again.

Dannettelle did somehow get his name in the Guinness Book of World Records fraudulently and in 1976 was arrested and convicted for stealing money “by deception” from a typewriter company, a music store, and Pennys. He had a history of passing bad checks. He became a manager of a video tape rental store and died due to alcoholism and drug abuse in 1996 at the age of 45.

1976 Camellia 100

America’s oldest 100-miler, the Camellia 100 had been held since 1971 in the Sacramento, California area, but sadly 1976 was its last year. The 1976 course was a loop of 4540 feet on a cement sidewalk. It was reported, “The very hard surface, and the temperatures which approached 80-degrees (with fairly high humidity) made this year’s race more difficult than usual.”

Ultrarunning legend, Don Choi, a postman from San Francisco, was led by John Arberry (1943-), also from San Francisco, by about 15 minutes in the early going. Choi went into the lead at 40 miles, extending it to an hour by 60 miles. From there, Choi kept the lead for good and finished in 21:36:31. Arberry was the only other finisher in 23:26:06. It was Arberry’s second 100-mile finish at this race. Previously in 1973, he finished in 22:21:39. In 1979 and 1980, Arberry tried his hand at running Western States 100 but did not finish either year.

The Camellia 100 was no longer held because the Camellia Festival Association withdrew their sponsorship due to insurance costs. The Pacific AAU distance running committee hoped to find a new sponsor and keep the race going but this early 100-miler ceased to be held

The parts of this 100-mile series:

- 54: Part 1 (1737-1875) Edward Payson Weston

- 55: Part 2 (1874-1878) Women Pedestrians

- 56: Part 3 (1879-1899) 100 Miles Craze

- 57: Part 4 (1900-1919) 100-Mile Records Fall

- 58: Part 5 (1902-1926) London to Brighton and Back

- 59: Part 6 (1927-1934) Arthur Newton

- 60: Part 7 (1930-1950) 100-Milers During the War

- 61: Part 8 (1950-1960) Wally Hayward and Ron Hopcroft

- 62: Part 9 (1961-1968) First Death Valley 100s

- 63: Part 10 (1968-1968) 1969 Walton-on-Thames 100

- 64: Part 11 (1970-1971) Women run 100-milers

- 65: Part 12 (1971-1973) Ron Bentley and Ted Corbitt

- 66: Part 13 (1974-1975) Gordy Ainsleigh

- 67: Part 14 (1975-1976) Cavin Woodward and Tom Osler

- 68: Part 15 (1975-1976) Andy West

- 69: Part 16 (1976-1977) Max Telford and Alan Jones

- 70: Part 17 (1973-1978) Badwater Roots

- 71: Part 18 (1977) Western States 100

- 72: Part 19 (1977) Don Ritchie World Record

- 73: Part 20 (1978-1979) The Unisphere 100

- 74: Part 21 (1978) Ed Dodd and Don Choi

- 75: Part 22 (1978) Fort Mead 100

- 76: Part 23 (1983) The 24-Hour Two-Man Relay

- 77: Part 24 (1978-1979) Alan Price – Ultrawalker

- 79: Part 25 (1978-1984) Early Hawaii 100-milers

- 81: Part 26 (1978) The 1978 Western States 100

- 87: Part 27 (1979) The Old Dominion 100

Sources

- Coventry Evening Telegraph (England), Jul 31, 1974, May 21, 1975, Oct 4, 27, 1975, Jan 3, 1976

- Andy Milroy, The Greatest 100 Miles

- “The Athletics in Leamington Cycling and Athletic Club: 90 Years and Still Running”

- Sports Argus (England), Nov 1, 1975

- Czech 100 mile results

- Ivo Domansky, “Just from the Stand: From a marathon runner to a tourist and an ultramarathoner.”

- Poughkeepsie Journal, Oct 6, 24, Nov 22, 24, 1967

- Courier-Post (Camden, New Jersey) Dec 11, 1967, Dec 9, 10, 1976, Nov 18, 2016

- Thomas J. Osler The Conditioning of Distance Runners

- The Philadelphia Inquirer (Pennsylvania), Jan 27, 1979

- John Carlson, “Tom Osler Interview Part 1”

- John Carlson, “Tom Osler Interview Part 2”

- “2008 Interview with Tom Osler”

- Richard Englehart, Marathon and Beyond, Sep/Oct 2008, “Like a Cat Chases Mice: Tom Osler Teaches Us That As We Age, There Is Glory and Fulfillment in the Chase Itself.”

- Tom Osler races, ARRS

- Tom Osler, Rowan University

- Tom Osler and Ed Dodd, Ultra-Marathoning: The Next Challenge

- Tom Osler, Serious Runner’s Handbook: Answers to Hundreds of Your Running Questions

- History of the Road Runners Club of America

- 2020 correspondence with Ed Dodd

- The South Bend Tribune (Indiana), Jul 2,9, 1975

- The Decatur Daily Review (Illinois), Jul 8, 1975

- The Courier-Journal (Louisville, Kentucky), Jul 3, 1975

- Indianapolis News (Indiana), Jul 9, 1975

- The Republic (Columbus, Indiana), Jul 9, 1975