Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 28:44 — 35.9MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

Walks and runs across Death Valley, in California during the hot summer started as early as 1966 when Jean Pierre Marquant (1938-) from Nice, France accomplished a 102-mile loop around the valley that included climbing two of the high mountains. (see episode 62).

Walks and runs across Death Valley, in California during the hot summer started as early as 1966 when Jean Pierre Marquant (1938-) from Nice, France accomplished a 102-mile loop around the valley that included climbing two of the high mountains. (see episode 62).

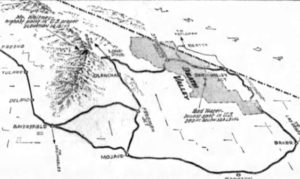

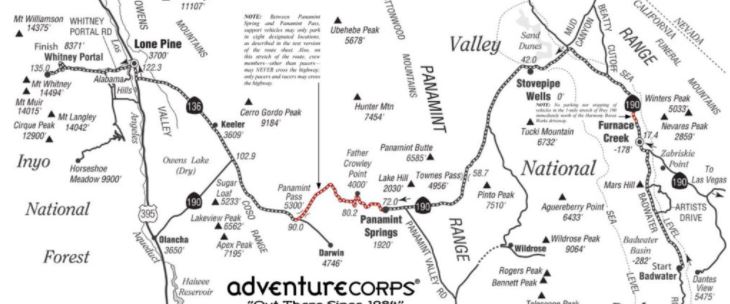

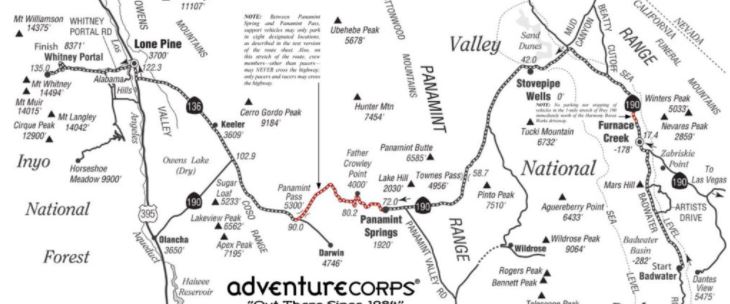

This started a Death Valley hiking and running frenzy in the lowest and hottest place in North America. It mostly concentrated on 100+ mile end-to-end journeys across the blazing wilderness. End-to-end records were set, broken, and recorded by the Death Valley Monument rangers. All of these accomplishments were the roots for what eventually would be the Badwater Ultramarathon. But when did trekking from Badwater (-282 feet) to the top of Mount Whitney (14,505 feet) start?

|

Early Ideas

In 1958 an article in the Boston Globe promoted the area with, “Do you like extremes? You can see Mt. Whitney, the highest point in the United States, and Badwater, the lowest point, from the same place at Dante’s View. You can travel in a few hours from the heat of the desert to the snow fields of the High Sierra.”

First Badwater-Mt Whitney Trek

The first documented hikers to go from Badwater to the top of Mount Whitney were James Harvey Burnworth (1926-2013) and Stanley David Rodefer (1925-2019) from San Diego, California, who in November 1969, backpacked the route in two weeks. Instead of using the roads, they took a direct route across the Valley. They said they did it “just for the heck of it.” They survived on food and water that they had buried in various locations ahead of time.

Paul Pfau

They completed their hike faster than planned, in eight days. Pfau said, “We ran into just about everything there was to run into. The weather was good for about half the trip but then we ran into snow and ice, crossing the mountains and we used a lot of rope. On the third day we ran out of water and we were away from contact with the support column. We were out of water for 16 hours. There was a lot of discomfort, but no serious problem.” Pfau and two others had planned to also climb Mt. Whitney but cancelled that plan due to bad, snowy weather.

Greg Sullivan, 18, said, “I have more of an understanding of how much I can handle now. I feel now that if I ever did get involved in a real survival situation I would be less likely to panic. I would probably come out of it OK.”

1973 Crutchlow-Beale Relay

In August 1973, Kenneth Crutchlow (1944-2016), originally from England, and Paxton “Pax” Beale (1929-2016), from San Francisco ran a two-man relay from Badwater to the top of Mt. Whitney. Crutchlow was a self-promoting endurance stunt artist. In 1970, he had raced Bruce Maxwell, a tennis professional, across Death Valley (lengthwise) for five days. Crutchlow also once swam from Alcatraz to San Francisco and accomplished many other stunts. Beale was a military heavyweight boxing champion who co-founded an early running club in the 1960s.

Crutchlow was intrigued that the lowest and highest points in the continental United States were so close together. He developed a burning desire to attempt a speed run from Badwater to the top of Mount Whitney and proposed making the run as a relay with Beal. At first Beale had zero desire to lug his 200+ pound frame across the desert until it was brought into context to his own field, which was medicine. Marathon legend, Dr. Joan Ullyot (1940-) had recently monitored the heart rate of Olympian Marathoner Ron Daws (1937-1992) as he ran a 2:26 marathon. An idea was hatched to allow Ullyot to study Crutchlow and Beal during a Badwater to Mt Whitney run. Ullyot agreed to join in on the project.

Dr. Ullyot set up her medical gear which included a portable generator, centrifuge, miniature EKG, emergency drugs and IVs, bathroom scales, specimen bottles, syringes, thermometers and more. She would carefully monitor fluid intake. Most importantly, she made them sign a medical waiver so she would not be liable for problems.

At 4 a.m. on August 18, 1973, Crutchlow set off running the first mile of the relay from Badwater Basin into the 105 degree darkness to the cheers of “nine solitary souls echoing in the vastness of the enduring desert.” When Beal took over the running, he recalled, “When the heat hit me, it was like running into a brick wall.”

Elaine Pederson was part of the crew. She was an experienced Bay Area marathon runner who in 1968 was one of several women who jumped in and ran the Boston Marathon when women were not allowed to run it. Pederson reported that she and others who were in the crew ran “empathy legs” to know what the experience was like. She changed her thoughts from “they can do it” to “how can they stand it?” They devised some “Arab” headgear which was soaked in ice water between relay legs. “The pace slowed, and it was not an optimistic group that stumbled into Stovepipe Wells (mile 42) at noon, where a thermometer in the shadiest, coolest nook recorded 116 degrees.”

Pederson wrote, “Then disaster struck. As we came into the unexpected searing heat of the next valley, they lost momentum. Our shaky research had not shown this second desert. It was the low point, mentally, for all of us. We knew that the 40-hour goal was impossible, as we would not be able to ascent Whitney by nightfall of the second day.” They halted at midnight (20 hours) to make new plans. There was no mention of quitting, but Ullyot proposed a five-hour sleep break. They drove to the top of Inyo Range where it was cooler and they all passed out.

In the morning at 5 a.m., they resumed from their stopping point with a skeleton crew. At times the runners switched every quarter mile, but were confident that they would finish. They successfully reached Lone Pine (122 miles) by late afternoon (36 hours) where it was a “frigid” 96 degrees. Their advance team had secured a motel with a pool for the crew. The runners continued on to Whitney Portal so that they could start the climb up Mt. Whitney at daybreak.

Crutchlow later became famous for his long-distance rowing across the oceans and founded the Ocean Rowing Society International in 1983.

1974 Maxwell-Miller Relay

In September 1974, Bruce Maxwell (1948-1998), a tennis pro, who had previously raced Crutchlow across the Valley, and Tate Miller (1948-), general manager of a dome home construction company, both from Santa Cruz, California wanted to also attempt the two-man relay.

“A coin flip determined that Miller would start at Badwater. He left that Death Valley low spot at 4 a.m. After three miles, Maxwell took over and so on and on.” They averaged about six miles an hour for the first 42 miles.

“While Maxwell and Miller alternated running, the support group followed in two vehicles, a VW station wagon and International truck. It was up to them to give the runners what they needed, primarily water and an occasional tad of yogurt and encouragement.”

By mile 43, Maxwell’s right knee “went out,” the same knee that had troubled him for many years. The extreme heat slowed their pace to 4 m.p.h. by mile 60. As they climbed up an over Panamint Pass it slowed to 3 m.p.h. and they decided it was time to sleep. Maxwell ran from 12:30 to 3 a.m. while Miller slept and Miller ran his long leg unto daylight. “It was sunrise when they left the mountain range, and at 9 a.m. around Lone Pine, each ate breakfast while the other ran.”

The two reached Whitney Portal at 1 p.m. in 33 hours, 15 minutes better than Crutchlow and Beale. They pushed on to climb the mountain. Maxwell said, “At that point, we were cocky and overconfident.”

“The higher we went, the colder it got. At about 11,800 feet our water bag froze, and for the first time we thought we were in trouble.” Their photographer, Nick Buratovich, a grape grower who hiked with them and was underdressed, was in bad shape. A passing hiker agreed to take him back down. When he arrived at the bottom, he reported that the two runners were in bad condition. Authorities tried to dispatch a rescue helicopter to go search for them, but then decided not to try it at night.

To make matters worse, a member of their crew, Scott Hewett, 26, had gone for a bike ride and crashed going down a hill at 40 m.p.h. when a deer jumped in front of him. He was taken to the hospital with a broken collarbone and serious road rash.

Meanwhile, Maxwell and Miller kept moving, but became lost in the dark and screamed for help until 10:30 p.m. They stopped and huddled in a sleeping bag that Buratovich had used to protect his photographic equipment. Maxwell said, “We thought if we went to sleep, we’d freeze to death. We tried to keep each other awake, but we both passed out. At that time, we’d had one meal in two days, and now our water was frozen.”

They woke up at about 6:30 a.m. and reached the summit in 30 minutes. Four hours later, and five miles down, they met one of their crew, Barry Nottoli, coming up, who helped them down. Maxwell said, “We were exhausted, just sick. For the next 24 hours we ate and drank everything we could get into our systems.” Their total time to the summit was reported to be 53 hours.

Maxwell and Crutchlow duel in Death Valley

They started at 9:15 a.m. Crutchlow fell behind when he became ill because of drinking too much water and not taking in enough salt. They ran only during the daylight hours and stopped for the night. After the first day with a 20-mile leader, Maxwell said, “I’m afraid I am burning down and set too fast a pace. I’m running on sheer character. I am worried that Crutchlow maybe used some strategy and fell back on purpose hoping I would burn myself out.”

1977 Maxwell-Miller Relay

They started fast and covered the 24 miles to Stovepipe Well in 6:23. Maxwell was slowed from a broken ankle still not totally healed. “We followed the road as it wound along the eastern side of the valley, following the contours of the mountain flanks that spilled onto the valley. Looking westward, I saw miles of flat, dry crack mud. Intermittent sagebrush and occasional wooden crosses marking primitive gravesites offered the only respite from the glistening flatness until mountains, rising abruptly, defined the far side of the valley floor.”

Maxwell was also suffering from bad cramps and could only run about 10 minutes before collapsing. “As I climbed out of the van to begin another turn, my hands were so cramped I couldn’t even squeeze a water-soaked sponge over my head. Knowing I’d never be able to run for my entire half-hour, I suggested we begin 14-minute turns. Mercifully, Tate agreed.” They limped into Panamint Springs (mile 73) at 3:15 p.m. (11:15 total). They were about four hours ahead of their previous record pace.

“An orange and violet sunset streaked the sky ahead of us as we followed the meandering road into the Sierra foothills. Tate finally gave up trying to run his entire turn. He began to allow himself the luxury of walking 10 of his 30 minutes.” Even though it was 90 degrees, Maxwell was shaking from chills and cramps that spread throughout his body because of an electrolyte imbalance. He changed up his drinking but that did not help. Finally, he could run only ten minutes and collapsed. His crew lifted him into the back of the van.

Miller did most of the running until 9 p.m. when Maxwell felt much better. “Thus, we went through the night, trading off every two hours. A crew member walked ahead of us with a flashlight, clearing the road of snakes and scorpions.”

After a half hour rest, they began their Whitney climb at 8:45 a.m., at the 28:45 mark. Two members of their crew accompanied them and carried their food, water, and cold weather gear. “The initial adrenalin-based rush of energy that propelled us up the lower part of the mountain soon dissipated. Fatigue, dizziness, nausea and the increasing altitude, slowed our pace.”

One crew member got sick at 12,000 feet and headed down. They reached the summit at 3:50 p.m. in 35:50. They had crushed their existing relay record. They said, “We slapped hands and fell into an embrace.”

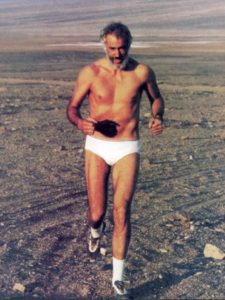

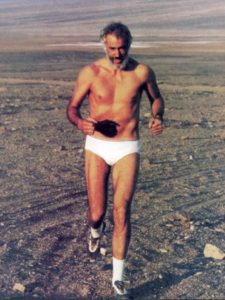

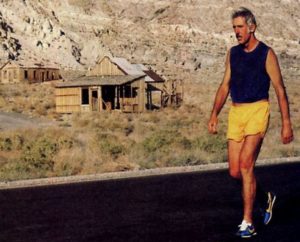

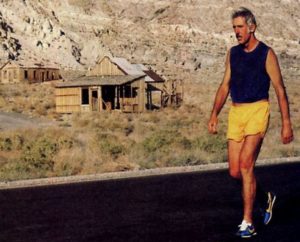

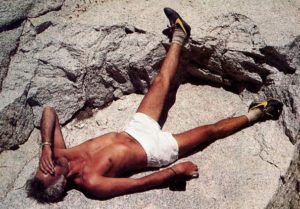

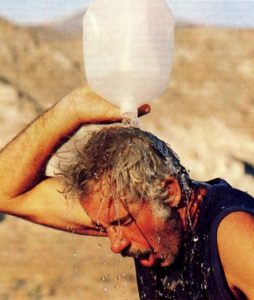

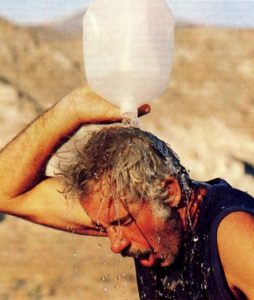

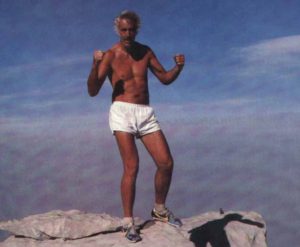

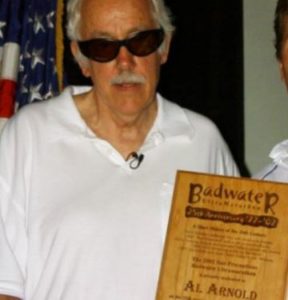

Al Arnold’s solo 1977 Badwater-Mt Whitney

He had tried and failed two times. The first time in 1974, he only made it 18 miles because of severe dehydration. “I felt like somebody hit me in the middle of the stomach with a 16-pound shot. I vomited and had no strength to move, could hardly breath.” The second time, he hyper-extended his knee after 50 miles when trying to shortcut across Devil’s Golf Crouse. In August 1977, he made his third attempt.

Arnold was confident this time and knew how to fuel, pace, and cool his body. He was a big guy, 6’5” and 200 pounds, and wanted to run across the valley without any pacers. He knew what endurance was all about. When he was in college in 1951, he and a friend set the world record for teeter-tottering, going up and down 45,159 times for three days and nights.

Arnold started at 5 a.m. on August 3, 1977 at a careful, slow pace. He said, “It wasn’t important to me how fast it was going to be. I just wanted to complete the darn thing, that’s all. I wanted to enjoy it and to share the experience with everybody I came in contact with, who stopped along the road.” He stayed on the main road traveling with a support car, using the future Badwater Ultramarathon format. (However, some of the photo show him out on the desert floor. The photos were likely staged during the run for a future magazine article.)

After covering 40 miles in 10 hours Arnold got sick and his knee really hurt. “His two-man support team, Erick Rahkonen, a newspaper photographer, and Glenn Phillips, a commercial pilot, were also sick after a long day driving slowly through the boiling heat.”

After about 70 miles at Panamint Springs, the Department of Transportation was stopping all the traffic going up Highway 90 ahead of him. There was demolition going on and it would be a six-hour delay. Not wanting to wait that long he grabbed two gallons of water and went off road into Panamint Valley. His crew honked their horns so he knew which way to go.

Finally he was in the foothills of the great mountain. “I heard the coyotes howling their fool heads off like they were laughing at me. I got to Lone Pine around sundown and changed into some street clothes. I just didn’t want anyone to notice me.” He was met by his wife and daughter who revitalized him with a hamburger and milkshake. He continued very slowly through the night to Whitney Portal.

After 74 hours, in the morning, he started up the trail with Phillips. Previously they had hid a backpack with warm clothes, a sleeping bag and food halfway up. At 12,000 feet before the many switchbacks, Arnold was very dizzy and nearly walked off the trail several times. Thankfully he was caught by Phillips. Eventually they arrived at the summit. His journey had taken 84 hours. Arnold said, “I just sat down on a rock, it was very low key, and bawled my fool head off for a couple minutes.”

They did not spend much time up there and started the trek down. Phillips unwisely bounded down fast ahead to call in a story to a newspaper. When Arnold reached the cache, the backpack had been stolen. He had no choice but to use a survival kit and huddle in a plastic lining for the night. He was able to hobble down the rest of the way in the morning, taking time to immerse a swollen leg in icy streams. Al Arnold had clearly demonstrated it was possible for a solo runner to make the Badwater to Mt. Whitney run.

Arnold tried to get his accomplishment published in the Guinness Book of World Records, but the publication rejected it for some reason. There was no mention found of his accomplishment in national newspapers. The entire story finally came out the following year in a Runners World publication. It took four years before his record was broken by Jay Birmingham in 1981, with 75 hours, 34 minutes.

Two weeks later after his historic run, Arnold was in Hawaii on a beach when he was hit by a wave a became totally paralyzed. At the hospital he was diagnosed with Brown-Siccard Syndrome. They said he would have to walk with a walker for a year. He refused to accept that news. A year later, he ran around the 72 miles around Lake Tahoe, without a walker.

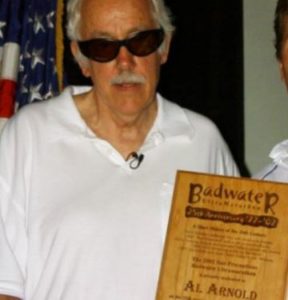

Arnold’s true passion was jogging for hours, and sometimes days on end. He was fondly nicknamed the ‘Joggernaut’ by explorer Jacques Cousteau. In 2002 Arnold attended the Badwater Ultramarathon and was the first inductee into the Badwater Hall of Fame. He passed away in 2017 at the age of 89.

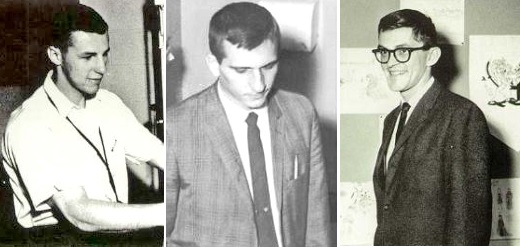

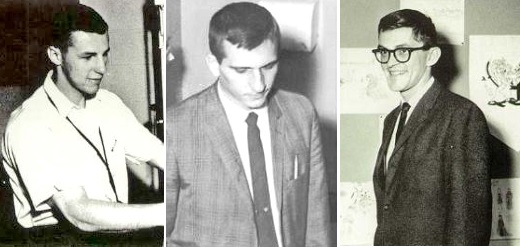

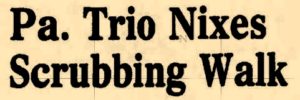

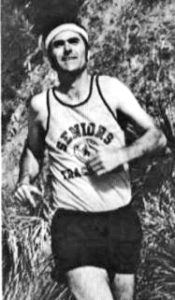

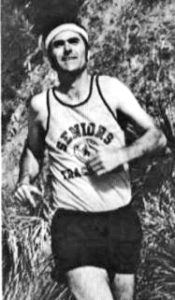

1977 Pennsylvania Three – Mt Whitney to Badwater

Also during August 1977, three teachers from a Palmyra, Pennsylvania Middle School, who were known as the “Pennsylvania Three,” traveled across the country to attempt what no one else had accomplished yet, a Mt. Whitney to Badwater hike (high to low). The three were David S. Vallan (1948-), William “Duke” B. Snyder (1949-), and David A, Meckley (1950-1997). Benjamin E. Groff (1948-) was their crew man. The three did have some previous Death Valley experience. They had previously walked 57 miles of the Valley in August 1975.

On August 9, 1977, the three started at Whitney Portal at 6 a.m. They were working with Multiple Sclerosis to raise funds. After making a base camp, they reached Mt. Whitney summit on August 10th and then started their journey down, heading for Badwater. The rather naïve easterners suffered from altitude sickness and muscle pulls making slow miles each day down.

They had planned to go through “Devil’s Golf Course,” an area of eroded salt formations, but there was a great amount of water in it, causing salt formations to dissolve, making treacherous footing.

The three were very upset about the cancelation without consulting them. They demanded to know why the hike was being cancelled by those who were not there. They said they were tired, had sores and blisters, but were all healthy. It was decided to let them continue.

They did cancel plans to climb Telegraph Peak. On August 20, 1977, after trudging through calf-deep mud at times, they all finished at Badwater. “Al, the proprietor of general store at Furnace Creek treated the four Pennsylvanians to champagne and a filet mignon dinner. To the best of his knowledge, the Whitney to Badwater had never been done before.” Al also awarded them finishing mule team belt buckles and said, “Now that you have walked across Devil’s Golf Course, I guess you know how the jackasses felt.”

1978 Parrish-Ballew Relay

In September 1978, another duo attempted to go after the two-man relay record. The two men were from California, Dennis Parrish (1941-), of Tujunga, California and Larry Ballew (1946-2004) of Newbury Park, California. They both were marathon runners and physical educations teachers. The two were unaware that the record had been lowered to 35:50 by Maxwell and Miller the previous year, or they didn’t recognize it for some reason. When asked why attempt the crazy run, Ballew replied, “It was about as difficult challenge as I could find. It seemed like the ultimate long distance run.”

They experienced the usual difficulties, heat exhaustion, knee problems, sore feet, and getting lost for 10 minutes while climbing Mt. Whitney. The hike up to the summit took them 8.5 hours. They said, “Our pace was faster than hikers with backpacks but slower than those without.” They finished at 4:39:15 p.m. for a second-best ever relay time of 36:39:15. They said, “I’m sure some crazy pair will try to beat that record. The key will be organization.” They thought they broke the record, but actually missed it by only 50 minutes because of taking their time at Lone Pine and on the climb when they thought they had the record in the bag.

The parts of this 100-mile series:

- 54: Part 1 (1737-1875) Edward Payson Weston

- 55: Part 2 (1874-1878) Women Pedestrians

- 56: Part 3 (1879-1899) 100 Miles Craze

- 57: Part 4 (1900-1919) 100-Mile Records Fall

- 58: Part 5 (1902-1926) London to Brighton and Back

- 59: Part 6 (1927-1934) Arthur Newton

- 60: Part 7 (1930-1950) 100-Milers During the War

- 61: Part 8 (1950-1960) Wally Hayward and Ron Hopcroft

- 62: Part 9 (1961-1968) First Death Valley 100s

- 63: Part 10 (1968-1968) 1969 Walton-on-Thames 100

- 64: Part 11 (1970-1971) Women run 100-milers

- 65: Part 12 (1971-1973) Ron Bentley and Ted Corbitt

- 66: Part 13 (1974-1975) Gordy Ainsleigh

- 67: Part 14 (1975-1976) Cavin Woodward and Tom Osler

- 68: Part 15 (1975-1976) Andy West

- 69: Part 16 (1976-1977) Max Telford and Alan Jones

- 70: Part 17 (1973-1978) Badwater Roots

- 71: Part 18 (1977) Western States 100

- 72: Part 19 (1977) Don Ritchie World Record

- 73: Part 20 (1978-1979) The Unisphere 100

- 74: Part 21 (1978) Ed Dodd and Don Choi

- 75: Part 22 (1978) Fort Mead 100

- 76: Part 23 (1983) The 24-Hour Two-Man Relay

- 77: Part 24 (1978-1979) Alan Price – Ultrawalker

- 79: Part 25 (1978-1984) Early Hawaii 100-milers

- 81: Part 26 (1978) The 1978 Western States 100

- 87: Part 27 (1979) The Old Dominion 100

Sources

- Joseph News (Missouri), Aug 11, 1930

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Apr 13, 1958

- The San Francisco Examiner (California), Apr 9, 1939, Jul 21, 1970, Aug 20, 1973, Sep 11, 1977

- Arcadia Tribune (California), Jan 31, 1971

- Reno Gazette-Journal (Nevada), Mar 24, 1971, Aug 31, 1976

- Daily News-Post (Monrovia, California), Jan 18, 29, 1972

- Arizona Republic (Phoenix, Arizona), Jan 18, 1972

- The Los Angeles Times (California), Jan 26, Feb 3, 1972, Aug 19, 1973, Sep 24, 1978

- Paul Pfau: Ghosts of Everest’s Past

- The San Bernardino County Sun (California), Aug 18, 1973

- Santa Cruz Sentinel (California), Oct 6, Nov 17, 1974

- The Argus (Freemont, California), Aug 27, 1976

- The Times-News (Twin Falls, Idaho), Aug 24, 1976

- The San Francisco Examiner (California), Aug 25, 1976

- The Bakersfield Californian (California), Aug 14, 1976

- Bob Wischina, “Al Arnold: The Road Goes on Forever”

- Chris Kostman, “Insights and Anecdotes From Al Arnold”

- Ulrich, Marshall, Both Feet on the Ground: Reflections from the Outside

- Lebanon Daily News (Pennsylvania), Aug 9, 18, 19, 1977

- NorCal Running Review No. 44