Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 32:00 — 41.9MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

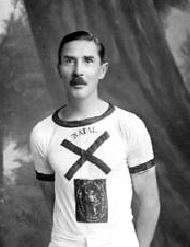

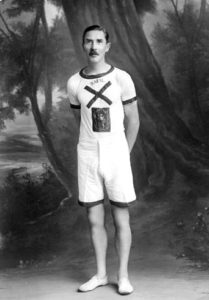

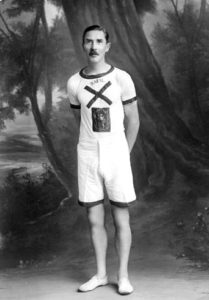

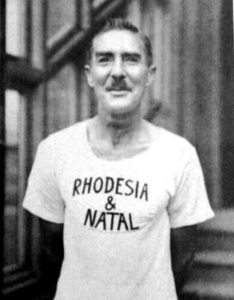

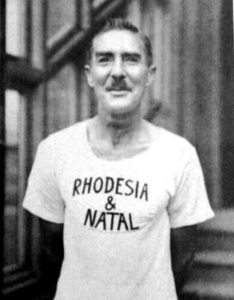

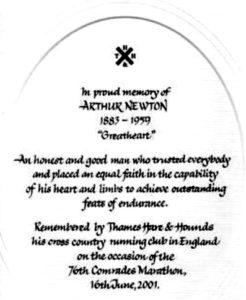

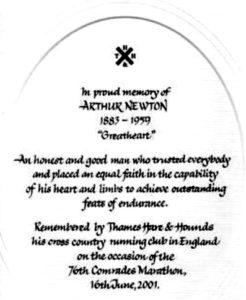

In the 1920s one of the greatest British ultrarunner ever appeared, who made a serious impact on the forgotten 100-mile ultrarunning history before World War II. He was Arthur Newton of England, South Africa, and Rhodesia was a rare ultrarunning talent who had world-class ability in nearly all the ultrarunning distances from 50 km to 24-hours. Newton learned most of his serious running on a farm in remote Africa and was bold enough to step onto the world stage and beat everyone. His dominance in the early years of South Africa’s Comrades Marathon (54 miles) helped the race get off the ground to become the oldest and largest ultramarathon in the world.

In the 1920s one of the greatest British ultrarunner ever appeared, who made a serious impact on the forgotten 100-mile ultrarunning history before World War II. He was Arthur Newton of England, South Africa, and Rhodesia was a rare ultrarunning talent who had world-class ability in nearly all the ultrarunning distances from 50 km to 24-hours. Newton learned most of his serious running on a farm in remote Africa and was bold enough to step onto the world stage and beat everyone. His dominance in the early years of South Africa’s Comrades Marathon (54 miles) helped the race get off the ground to become the oldest and largest ultramarathon in the world.

But Arthur Newton’s best distance was 100 miles. With few 100-mile races to compete in during the 1920s, he resorted to participating in highly monitored solo events to prove that a farmer from Africa was the best in the world, and he was. His 100-mile experience will be shared, but also a good portion of his life story needs to be explained to understand the man, the ultrarunner, one of the greatest, Arthur Newton.

Early life

After graduation in 1901, at the age of 18, he thought he would become a teacher. His father instead wanted him to be a clerk and sent him to South Africa to join two older brothers who were living in Durban. He tried the clerk career for a couple years but it was not for him, so he began teaching in the province of Natal. He played the piano, was an avid reader, and loved riding motorcycles. But he also was a regular smoker living a rather sedentary life. He explained, “I sacrificed the exercise necessary to a young man in order to dive deeper into metaphysics and allied subjects. Common sense soon came to the rescue and I knew I should be able to make a better job of my mental work if I made certain of a healthy physique. So I started a daily walk, whether I liked it or not.”

The running teacher in South Africa

Newton began walking to his work and progressed to jogging distances up to six miles. “Sometimes people would stare quizzically at the eccentric Englishman running down the road.” He became bothered by these reactions and so moved his exercise during the early hours when few people were out. He began very fit and demonstrated his abilities to the schoolboys he was teaching. He once organized a 300-mile round trip to the Drakensberg mountain range that involved bike riding and hiking.

Newton’s first running race took place when he was age 24 in February 1908. It was a 11-mile “Go as you please” race in the small rural town of Howick. The town was the site of a sad British internment camp where many women and children died a few years earlier during the Anglo-Boer War. He was one of eight runners who took part and he finished in fourth place with a time of about 90 minutes. He soon started to win some races. On a long excursion to the mountains he ran out of cigarettes and was convinced by a friend to start using a pipe instead.

He said, “Several weeks at home just idling around proved too much, and I told my father that I wanted to get back to South Africa. He said he had guessed as much, and perhaps I had better go. So back to Natal I was sent and accepted a position as a tutor on a farm near Harding.”

South African Farmer

When his service ended, he returned to his farm in 1918 and found it in a state of neglect being grazed by Zulu cattle herders. Grass fires had destroyed about two-thirds of his grazing land. Newton wanted to convert his land to be more profitable, to cultivate cotton and tobacco. But the Zulu tenants on his land objected changing their centuries-old lifestyle. They did not want to become farm laborers earning wages and his tenants would disagree with him about nearly everything. On top of that it became increasingly difficult to collect rent from them. It was a clash of culture, race, and politics.

The government started relocating more blacks to live in the area around Newton’s farm and the with current conditions in the country, they did not trust the white Englishman. Newton also did not trust the government or the Zulu to help find a way to make his farm work.

He asked the government to exchange his farm for another farm in a “white area” but the Department of Native Affairs refused. This led to a standoff between the farmer Newton and the South African government. He realized that it would be impossible for him to become a successful cotton famer and find willing local laborers.

Decision to become a serious runner

In January 1922, at the age of 38, Newton seriously thought he could win Comrades with less than five month’s serious training after nearly of ten years without consistent training. He said, “Knowing through my studies that any average man could do as well as other average men if he were really determined and was in possession of an average physique – and with the Comrades Marathon already in existence – I decided that what with my age, it would be quicker and probably easier to achieve publicity through long-distance running than by any other methods.”

The Comrades Marathon

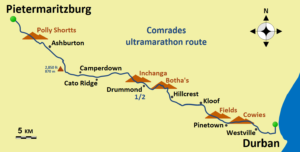

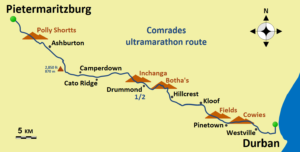

The first Comrades Marathon had been held on “Empire Day” on May 24, 1921. It was the idea of Vic Clapham (1886-1943) a train driver from Durban. Clapham had been inspired by the 52-mile London to Brighton races before World War I (See Part 5) and wanted to create a similar race as a living memorial to fallen soldiers of the war. The inaugural Comrades race with 34 runners, most of them former infantrymen, received good newspaper press coverage and Newton noticed.

For the early Comrades Marathon years, runners were followed by friends on bicycles or automobiles to provide support. Farmers set up aid station along the route and picnic parties were held by spectators who also handed out food to the runners. The first year was won by a farmer, Bill Rowan, in 8:59. Sixteen runners finished by the 12-hour limit on the mostly dirt road course.

Training for 1922 Comrades

Because farming had been rendered useless to him, he devoted most of his hours each day for five months in training. He knew that the previous winner, Rowan had trained doing 20-mile runs on his farm. Newton said, “My condition was quite reasonably good. I could walk 15-20 miles in a day over rough country without becoming exhausted, so I was surprised to find that two miles of running were altogether beyond me. After that I was so abominably stiff that I cut out running for a day or two and walked instead.”

He finally admitted to himself that if he was to succeed, he would have to put aside his smoking after 20 years of the habit. Going cold turkey was too difficult and he finally decided to allow himself two pipes a day including a post-run pipe as a reward for hard training.

Running started to come easier. He timed all his runs, trying to improve them on particular routes. By March, with race day just ten weeks away, he attempted a long run under race conditions. His competition was the local train that went on a route through the hills with several stops. He wanted to race the train for about 40 miles. All was going well until he experienced serious pain in his chest on a steep climb. Fearing that it was a heart problem, he backed off and did not beat the train. He wrote, “I was driven back to my farm and sat down to think the position out. Evidently my training had not been on the right lines, and I decided to ignore practically everything I had read and start all over again with sound common-sense methods.”

Newton went away from his time-trials, ignoring his watch. Instead he concentrated on distance, not speed. He discovered the benefit of the long, slow run. His runs worked up to 25 miles and he dropped his weight by ten pounds to 132 pounds. After more than a month, he returned to race that train and beat it. It was his longest run during his training and he knew that he was almost ready.

1922 Comrades

By mile 32 he moved into second place, passing a runner who had been 45 minutes ahead but now was stopped on the side of the road being massaged. By mile 38, during a grueling climb, Newton spotted the leader, Purcell, as a white speck going over the top. Newton soon went into the lead. He quickly built a large 30-minute lead over the runners limping behind him. With four miles to go and Pietermaritzburg in view, he knew victory was his. After some brandy at a hotel, he attacked the final stretch.

Newton wrote, “With a swarm of cars and cycles behind, I guessed there would be a crowd ahead. The moment I was sighted, I saw people beginning to run and in less than half a minute there was a dense crowd. The people swarmed up so suddenly from every side that I was only just able to get through with the aid of the police.” At the Sports Ground he ran on the track and thousands cheered him on as he ran the last stretch around the track. He said, “At last I saw the tape ahead and ran to it in a tumultuous roar and cheering from all sides to get a handshake from the city mayor.”

Newton finished in 8:40, nearly 20 minutes faster than the first year’s winner. A crowd lifted him off his feet and paraded him on their shoulders off the field. Reporters followed and photographed. His friends took him away to recover. By the time the second place runner finished, Newton had already had a bath and dressed in every-day attire. He told reporters that he did not think he would try to run that far again. “After all, I’m 39 and getting on in years.”

The local newspaper took up his cause and wrote that it was deplorable how the government treated Newton, a former soldier, in regards to his farm difficulties. He became a national star overnight and quickly became determined to continue competing and lobbying the government. But he had to put away his farming dream in order to train. For finances, Newton mortgaged his farm to a government bank.

Full time Runner

Newton dominated and reached the finish faster than anyone thought possible. The officials were not yet prepared for his arrival. “One man, however, happened to spot me shortly before I reached the Sports Ground and diving through a broken fence as a short cut, was able to gather another man inside and arrive at the finishing post just in time to hold up the tape and read the watches.” He finished in 6:56, nearly an hour ahead of the second place runner. Newton’s fame started to spread to England.

But the fame was not enough to produce the results he hoped for. He said, “I took stock of my position, felt that I had by no means established myself as a well-known public character, and decided that more training work, even harder work, had to be the order of the day. It looked as though nothing less than world’s records would bring me the publicity I knew was required.” His weekly mileage was consistently more than 100 miles and reached as much as 253 miles in a week. With this high mileage, he managed to avoid serious injury but was kept off the road for six weeks due to a muscle strain.

50-mile world record

In 1923 Newton wanted to go after the amateur 50-mile world record of 6:13 but didn’t want to run on a track because he thought that the monotony of running circles on a track was awful. So instead, a 25-mile length was measured on the road from Pietermaritzburg to Durban, the same road used by the Comrades Marathon. He knew every inch of the hilly road and felt confident on it.

Newton’s attempt was made on June 29, 1923, just five weeks after Comrades. He was crewed by friends who escorted him in a support vehicle. He started at 7 a.m. in a cool mist and said, “I was glad to get to work, though more than a trifle nervous.” The official cars had to stay well behind or in front of him to avoid kicking up large clouds of dust. To counter skepticism about the measurement with automobile odometers, he stunned officials by running an extra 200 yards at the 25-mile turnaround.

First 50-miler in England

Newton wanted to prove to British skeptics that his 50-mile record was valid. Before he left South Africa, the government officials changed their tune and promised to repair the wrong he had experienced if he would come back. Newton said he would. He returned to England on a ship and each evening when the deck was less crowded, ran 20 miles.

In England, he adjusted to training on busy English roads. The harder road surfaces gave his joints problems. He had to reduce his weekly mileage to about 120 miles until he felt better. He wrote, “Thinking I was now pretty safe, I let out for a couple of weeks in the old style, 251 and 295 miles. The latter was certainly rather more than usual.”

He was finally ready to attack 50 miles again. Arrangements were made for a solo London to Brighton run by representatives of the AAA. He was bothered by a swollen shin and ankle but went ahead with the run.

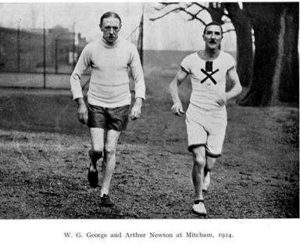

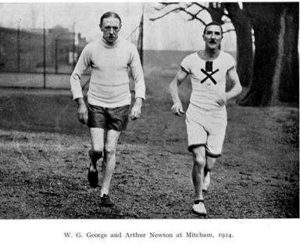

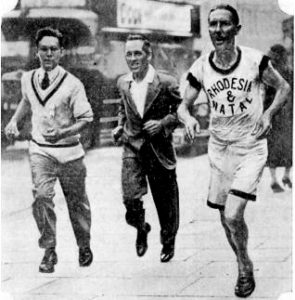

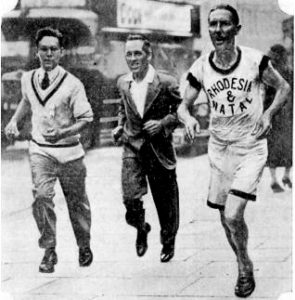

The London press were introduced to Newton’s running strategies. At five-foot-nine and 140 pounds, he was described as “hard as nails.” He ran in the lightest shoes possible with thin soles and ran with a shuffle. He didn’t receive heavy massages like the other runners of the time, just a quick rub-down along the way with a towel. He fueled mostly on cups of tea. At times he would use a “magic drink” of lemonade, sugar and salt which helped prevent cramps.

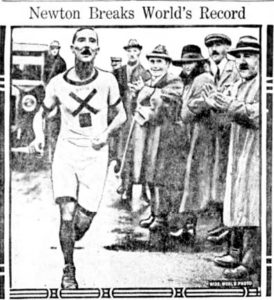

Newton’s attempt for the London to Brighton record was made on October 3, 1924. The current London to Brighton course record holder, Len Hurst, followed along in one of the timekeeper automobiles giving him encouragement. He was described as “adopting a shuffling gait, Newton made his running appear effortless.” He proved his point and finished in 6:11:04, which was faster than the course record by about 23 minutes. He passed through the 50-mile mark in 5:57:48, a bit slower than his time in South Africa.

Second 50-miler in England

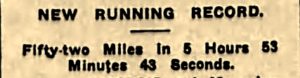

British skeptics thought due to recent road improvements that the route had been shortened, but remeasurements found it to be 52 miles, 200 yards. He became “the talk of the town” and was interviewed on BBC radio. Not satisfied with his performance, wanting to break six hours on the course, Newton, age 41, repeated the run the following month on November 13, 1924 in bad weather that was proceeded by 36 hours of continuous rain.

Back to South Africa

Newton left England on November 27, 1924, sailing on the SS Bendigo bound for South Africa. With changes politically in the government while he was away, the promises made to him were gone. Unable to pay the interest on his mortgage, he decided to sell his farm. Appeals for help from the new government went nowhere as he was considered as just an English settler who was a vocal government critic. He said, “Once more my funds were exhausted and consequently there was nothing for it but to clear out of South Africa and make for the nearest country where reason and justice were understood and valued.” Newton decided to start making plans to leave South Africa and go to the nearby country of Rhodesia which was a British colony.

Just 36 hours later, Newton left Pietermaritzburg where he had lived for seven months. He did not want to make a public fuss, so left privately one night with the quest to walk 770 miles to Rhodesia. He was poverty stricken, had been living on the kind charity of a hotel owner, and knew that the arrangement could not continue. He would go into exile. He wrote, “Six years of a real sporting fight had changed me from an active and prosperous farmer to an energetic and all-but-penniless tramp.”

The South African news soon noticed that he was gone, initially worried about him, and speculated why he disappeared until several days later he was seen on the road. After a few days he started to accept offers to ride in cars and receive kind room and board. It took him nearly three months to arrive at Rhodesia. The Natal newspaper in South Africa was so sad to see him go and organized a “shilling fund” of donations for Newton and sent him 1,200 pounds which he humbly accepted.

First 100-miler – Rhodesia

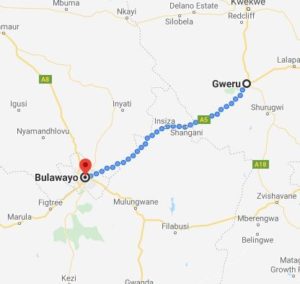

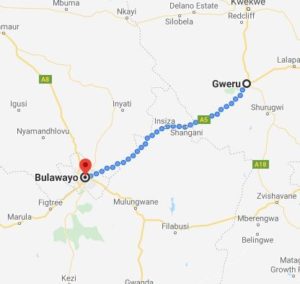

In 1927, after two years in Rhodesia, Newton went back to South Africa and won Comrades for the fifth time. With the encouragement of a running friend of the Bulawayo Harriers club, he set a goal to run 100 miles. He had never run further than the 54 miles at Comrades and knew that special training would be needed to do such an “extra-long run.” He first attempted 60 miles on an out-and-back course that began and ended at the King’s Grounds Gates in Bulawayo, Rhodesia. He started at 3 a.m. in order to finish before work and reached 60 miles in 7:33:55, 50 minutes before the fastest known amateur time.

On July 11, 1927 at 6:10 a.m., Newton set off to run 100 miles for the first time after eating a large breakfast. He gave the relay runner a head-start so as not to distract him. He said, “It was dark at first but an official car about fifty yards behind me flood-lighted the road which had quite a decent dirt surface, and I ambled along at a serenely easy seven miles per hour.”

Between miles 25-45 the temperature rose to an uncomfortable level. He stopped to cool off in a roadside pool. At the half-way point he stopped at a hotel for a pre-ordered lunch. “My fodder was soup, chicken and vegetables, and fruit pie. Twelve minutes later, I was on the road again, climbing a gentle gradient on my way to Bulawayo.” On the road he was fueled by hot tea from thermos flasks.

After 70 miles, the sun began to set. He wrote, “The car floodlighted the road while I crept steadily on, feeling that there was still a chance that I might reach the end, though I was in for a real bad time.” He drank piping hot tea every three miles or so and pressed on in a steady ten-minute-mile pace. He said, “Every nerve and fiber seemed to be crying for rest.”

A crowd of 300 greeted him at the finish at King’s Grounds. He had beaten his relay team by a few minutes and finished in 14:43:00 which was believed to be an amateur 100-mile world record. He had improved the fastest known amateur time of 16:07:43 held by Sidney Hatch. (See Part 4). The world’s best 100-mile time overall was 13:26:30 set by Charles Rowell in 1882, indoors at Madison Square Garden (See Part 2).

Funds were raised to allow him to travel to England. “I wanted to make good the time or perhaps even beat it, on some well-known course such as the Bath Road. As I was more than willing to do anything I could to show my appreciation of all the kindness I had met with in this splendid country, it wasn’t long before I found myself sailing to England”. He left during the autumn of 1927 and turned professional, having an eye on perhaps entering C.C. Pyles 1928 race across America.

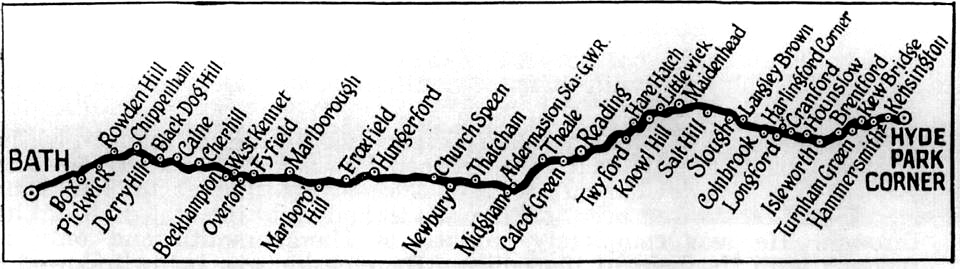

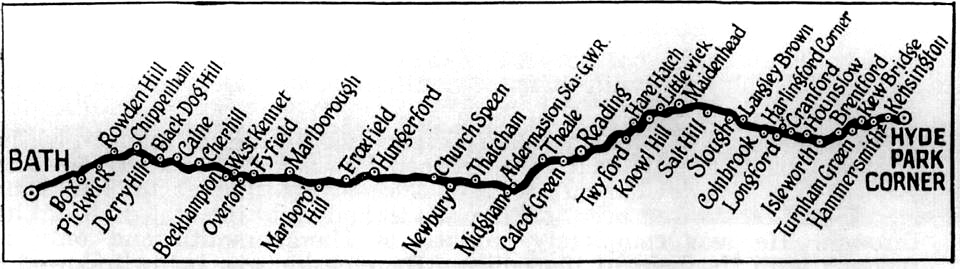

100 miles on Bath Road

Newton started his 100-mile journey on January 7, 1928 at 2 a.m. from Bear Inn in the village of Box, near Bath. Olympic sprinter, Harold Abrahams (depicted in Chariots of Fire) was at the start to watch Newton begin. Despite the early morning start, many men on bicycles followed after him. The snow was mostly gone but some fierce winds with rain made the going rough. Still, many people in each town came out to loudly cheer and watch the spectacle.

About his running style it was observed, “He glides along, feet no more than two or three inches off the ground, and noiseless. Not flat footed, but more on his heels, and astonishing silent breathing.”

He kept pace with the relay runner who was only going the first 25 miles but then he started to struggle, feeling ill. By 40 miles his illness was pretty evident to his crew but he was still ahead of schedule. Hot tea helped and he stopped for ten minutes to eat a breakfast of minced beef. The sickness continued and the relay team had a big lead. He tried drinking his “magic drink” often but could not take in any solid food.

It was reported, “His lower half was by now filthy from the muddy water splashed up by his own feet, and he became wetter still when going through Maidenhead, parts of which were completely underwater.” Temporary wooden walkways had been put in place over the water which Newton used.

“At seventy miles Newton was sick and his progress over the last thirty miles was unusually slow. He kept plugging away doggedly though obviously distressed.”

Later he explained, “I was pleased enough to get through it in twenty minutes less time than the 100 in Rhodesia, but that was all that could be said about it.” He had never experienced such severe stomach trouble. He wore wool clothes to keep him warm but they caused him to sweat profusely during the day. He likely had an electrolyte imbalance. He knew that he could run 100 miles much faster. Congratulations poured in, including from the chancellor of Rhodesia.

It should be noted that the Bath Road from Box to Hyde Park Corner is 100.25 miles according to the engraved

mile stone, in Box. However it is believed that the road in Newton’s time was almost certainly short of 100 miles. The road has been altered through the years.

The Bunion Derby

Two runners who ran in the Bunion Derby, later ran solo 100-miles. Peter Gavuzzi of the U.K., who barely finished second in the 1929 Bunion Derby with a controversial finish (see episode 32), ran a solo road 100-miler during August 1935 from Buffalo, New York to Toronto, Canada on the 30/31. His time was 15:25:34. Ollie Wanttinen of Finland, the 5’2″ 90-pound “Mighty Mite,” ran a solo 100-miler in Helsingfor, Finland (now Helsinki) on May 24, 1934, with a time of 15:13:33.

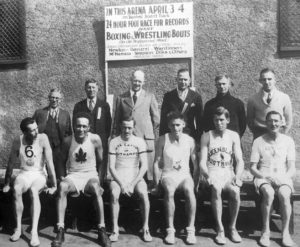

24-hour World Record

In 1931, Newton organized his own event in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada to attempt to break the 24-hour long-time world record of 150 miles set by Charles Rowell back in 1882. With the Great Depression raging around the world, Canada was initially affected less and many of the elite ultrarunners went there to compete. The 24-hour race was an invitation only event. America’s best, Johnny Salo could not make it, but other Bunion Derby veterans, including Paul “Hardrock” Simpson came. (see episode 3).

On April 4, 1931, an indoor 24-hour event took place. They ran surrounded by mostly empty seats. Mike McNamara from Australia reached 100 miles first in 14:09:45 and then decided to quit. Newton had hoped that McNamara would continue, giving him someone to battle for the 24 hours. Two others were still running but far behind. He wrote, “Quite unexpectedly, I was left alone to try for the 24-hour title.” He tried not to look at the clock and pushed ahead at about 8.5-minute-mile pace. As he got close to the 150 mile world record, he increased speed up to an astonishing six-minute-mile pace.

The event was a financial disaster and Newton lost a bundle. “It takes courage for a man to run 24 hours, especially when he knows that, instead of being rewarded for his efforts, he must lose money.”

1933 100-milers on Bath Road

For training in March 1933, he ran an amazing 1,084 miles including a 270-mile week. But he postponed his race when invited to run in France for a large sum of money. Instead postponed the 100-mile run to the heat of the summer on July 1, 1933. He covered the first 50 miles on the Bath Road in 5:56:30, 45 minutes ahead of schedule. But a mile or two later, the wheels started to fall off and he began limping. He reached 60 miles in 7:15:30 which he was told was a new record. But Newton’s Achilles hurt and his stomach went south in the heat. He reached 74 miles in 9:41:50, almost an hour ahead of schedule but was on a downward spiral.

Newton refused to think of giving up after covering more than 80 miles. He reached 85 miles in 11:24:30 during mid-afternoon, the hottest time of the day with temperatures in the 80s. Soon he started to sway and his crew insisted that he quit. He had no choice and it was the first time he ever quit a record attempt. He reached 86 miles in 11:33:00. He was diagnosed of having sunstroke. After recovering, he agreed that his health was being put at a serious risk.

Unwisely, Newton decided to try 100 miles again just three weeks later on July 22, 1933. He was desperate to “make amends.” His Achilles became inflamed with a week to go, but he was determined. He started at 3:00 a.m., again at Bear Inn in Box. More than 100 people were at the start. Things went well early, but by mile 25 he was noticeably limping. By mile 30 it was clear that he wouldn’t make it and could not run through it. He was very distressed and close to tears and quit again. He said, “I was quite shocked at the disaster and at having given the officials so much work and travel for nothing.” His injuries would last for a long time. He limped for the next ten months. He used the down time for coaching and writing.

1934 100-miler on Bath Road

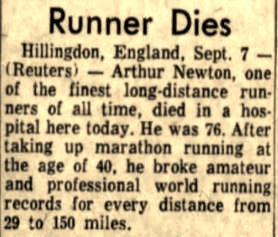

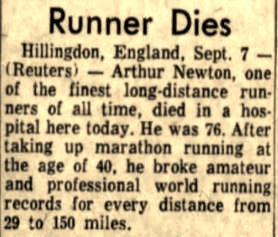

But Newton was also disappointed that he did not break 14 hours. He knew at 51, his age was now a slow-down factor. He knew that would be his last 100-miler. He said, “There remained only one useful alternative, and that was to put my experience at the disposal of other athletes so that they could carry on where I had left off.” Others did come in future years and broke his Bath Road 100 mile record.

Retirement from competitive running

The parts of this 100-mile series:

- 54: Part 1 (1737-1875) Edward Payson Weston

- 55: Part 2 (1874-1878) Women Pedestrians

- 56: Part 3 (1879-1899) 100 Miles Craze

- 57: Part 4 (1900-1919) 100-Mile Records Fall

- 58: Part 5 (1902-1926) London to Brighton and Back

- 59: Part 6 (1927-1934) Arthur Newton

- 60: Part 7 (1930-1950) 100-Milers During the War

- 61: Part 8 (1950-1960) Wally Hayward and Ron Hopcroft

- 62: Part 9 (1961-1968) First Death Valley 100s

- 63: Part 10 (1968-1968) 1969 Walton-on-Thames 100

- 64: Part 11 (1970-1971) Women run 100-milers

- 65: Part 12 (1971-1973) Ron Bentley and Ted Corbitt

- 66: Part 13 (1974-1975) Gordy Ainsleigh

- 67: Part 14 (1975-1976) Cavin Woodward and Tom Osler

- 68: Part 15 (1975-1976) Andy West

- 69: Part 16 (1976-1977) Max Telford and Alan Jones

- 70: Part 17 (1973-1978) Badwater Roots

- 71: Part 18 (1977) Western States 100

- 72: Part 19 (1977) Don Ritchie World Record

- 73: Part 20 (1978-1979) The Unisphere 100

- 74: Part 21 (1978) Ed Dodd and Don Choi

- 75: Part 22 (1978) Fort Mead 100

- 76: Part 23 (1983) The 24-Hour Two-Man Relay

- 77: Part 24 (1978-1979) Alan Price – Ultrawalker

- 79: Part 25 (1978-1984) Early Hawaii 100-milers

- 81: Part 26 (1978) The 1978 Western States 100

- 87: Part 27 (1979) The Old Dominion 100

Sources:

- Arthur Newton, Running in Three Continents

- Rob Hadgraft, Tea with Mr. Newton: 100,000 Miles – The Longest ‘Protest March’ in History

- Mark Whitaker, Running for their Lives: The Extraordinary Story of Britain’s Greatest Ever Distance Runners

- Comrades Marathon results

- Ian Champion, Arthur Newton’s 100-mile Road Running Record

- John Cameron-Dow. Comrades Marathon: The Ultimate Human Race

- The Guardian (London, England), Oct 4, 1924, Oct 4, 1924, Dec 10, 1927

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Nov 15, 1924

- The Bridgeport Telegram (Connecticut), Jul 12, 1927

- Hartford Courant (Connecticut), Aug 16, 1927

- The Spokesman-Review (Spokane, Washington), Mar 20, 1925

- The Province (Vancouver, Canada), Apr 6, 1931

- The Iola Register (Kansas), Jan 17, 1934

- Sioux City Journal (Iowa), Mar 4, 1934

- The Windsor Star (Ontario, Canada), Aug 17, 1934

- The Gazette (Montreal, Quebec, Canada), Sep 8, 1959