Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 33:35 — 41.0MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

The 100-miler! Running or walking 100 miles in one-go is an amazing accomplishment. Unfortunately, some people of today still mistakenly believe that the 100-miler was invented in 1974 when a man without his horse ran 100 miles. Contrary to the cunning marketing hype that has been spread for decades, the history of the 100-miler ultra on all surfaces started long before that year. The sub-24-hour 100-miler was accomplished by hundreds of people before that famed journey in the California Sierra in 1974. In April 2020, Runner’s World magazine erroneously called that run “The First 100-mile Ultra.”

The 100-miler! Running or walking 100 miles in one-go is an amazing accomplishment. Unfortunately, some people of today still mistakenly believe that the 100-miler was invented in 1974 when a man without his horse ran 100 miles. Contrary to the cunning marketing hype that has been spread for decades, the history of the 100-miler ultra on all surfaces started long before that year. The sub-24-hour 100-miler was accomplished by hundreds of people before that famed journey in the California Sierra in 1974. In April 2020, Runner’s World magazine erroneously called that run “The First 100-mile Ultra.”

The “mile” measurement has roots back to Roman times. The statute mile, a British incarnation in 1593, became adopted in the United Kingdom and later also by the United States. It should not be too surprising that walking and running, specifically the round number of 100 miles came out of Great Britain and America.

In more recent centuries, “running footmen” were used by aristocrats to deliver letters. In 1728 it was reported that Owen M’Mahon, an Irish running footman covered 112 mile in 21 hours running from Trllick to Dublin. Attempts to walk 1,000 in competition started as early as 1759 in England.

But what about achieving the round-number distance of 100 miles? When did the 100-mile quest begin and how did it evolve?

Earliest 100-milers

Captain Robert Barclay

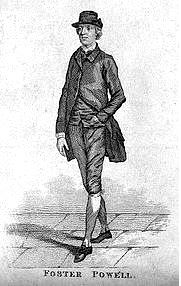

Barclay is recognized in history as “the father of the 19th century sport of pedestrianism.” He also was an officer in the army and thus called “Captain.” His greatest long-lasting fame came from originating the ‘Barclay Match,” walking one mile for 1,000 consecutive hours. Barclay took on numerous walking wagers and in 1806 he set his sights on the 100-mile distance he completed the distance in 19 hours. His servant, William Cross accompanied him and finished with the same time.

First 100-miler in America

For the early decades of the 1800s, 100-mile walks continued periodically, concentrated mostly in England. They were all conducted on dirt roads and most were solo attempts attached to a wager.

In 1835 it was reported that a Native American had covered 100 miles in a day, carrying a bar of lead weighing 60 pounds. In 1837, Jacob M. Shiveley (1786-1873) of Chambersburg, Pennsylvania also covered 100 miles in a day. He was referred to as “the great pedestrian.” 100-mile races between at least two people began as early as 1847 when W. Jackson “the American Deer” and J. Brian of London competed near Birmingham, England.

A typical 100-miler in the 1840s

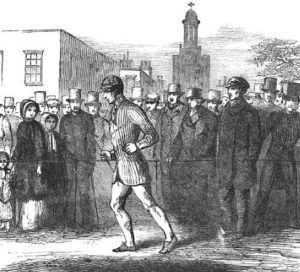

Mullen’s journey started at 4 p.m. and he continued at a brisk pace for the first six hours when he was reported to be somewhat flushed. By 11 p.m. his spectator crowd thinned and he appeared to be fresher in the cooler weather. But in the morning, he was fatigued, with painful feet. Five blisters were cut off and he kept on going fast. At the 22-hour mark he said he was “all safe.” He was loudly cheered as he continued. Four or five times during the day he stopped for a few minutes at the grandstands, quite confident of his powers.” Before the final mile, he stopped for six minutes and then completed an impressive finishing mile in eight and a half minutes. His final time in unknown but he finished within 24 hours. “He was loudly cheered on coming in. During the evening he walked through the town apparently not much fatigued.”

Running 100 miles

A few early 100 miler athletes actually ran the distance. Edward Rayner (1785-1852), “the Kentish Pedestrian” was born at Lenham, Kent, England. In 1819 he competed against Foster Powell in a match to go from Canterbury to London Bridge and back within 24 hours, a distance of 111 miles. On April 14, 1824 he took up a 100-mile challenge at Biddenden, England, to try to reach the distance in 18 hours, a quest that had been attempted many times by others who had all failed. It was described to as “the greatest undertaking ever performed in England.” He started off at a “jog-trot” of about ten-minute mile pace at 6:00 p.m. The road at first was very muddy because of a tremendous shower of rain and hail before the start. He kept up a steady pace, resting at intervals for refreshment, only about 2-3 minutes each time. At mile 59 he was attacked with a “slight sickness” and bets were offered 3-to-1 against him and refused. He labored in his sickness until recovering at mile 68. He finished in full speed “amidst the ringing of bells, waving of handkerchiefs, the bad playing ‘See the Conquering Hero Comes,’ and other demonstrations of joy and congratulations.” His time was 17:52, a mark that was not to be matched until 1878.

On June 17, 1861, Henry Howard, a famous long-distance runner from Portsmouth, England ran 100 miles in a fastest known time of 18 hours at Brighton, England. Previously in 1859, he had also accomplished running 83 miles in 12:25 in front of 4,000 people in London.

The Tarahumara 100-mile race of 1867

The true name for this people was the Rarámuri, thought to mean “the running people,” although some Tarahumara have said it means “runner with the ball.” The Spanish, not understanding their language, named them the “Tarahumara.”

One of the women who ran, had given birth to a child just ten days earlier. Heavy betting took place. Horses, cattle, sheep, pigs, goats, cats, dogs and other items changed hands.

After about 92 miles, only three women were left in contention, but by the last lap, the lone contending runner from Sisoguichi had fallen off the pace. The two winners were from Bocoyna, and were “received with the loudest shouts of joy by their towns people.” The women were reported to finish in well under 24 hours. At the finish, nearly everyone was “on the ground drunk.”

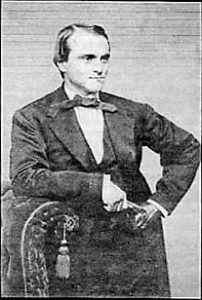

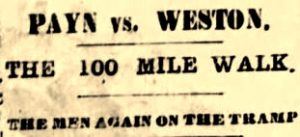

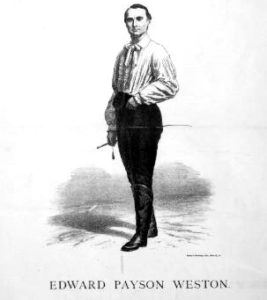

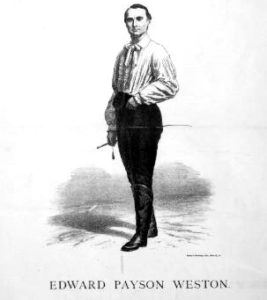

Edward Payson Weston’s 100 milers

Others later claimed that with a closer look at the distance that day, the 91 miles were actually 100 miles. Weston would complain bitterly about the distance when he finished his journey in Chicago.

Weston next attempted to walk 100 miles in less than 24 hours at Riverside Park in Boston on June 4, 1868 for $2,500. A huge crowd of 5,000 people was present to watch including a brass band. But he managed to only reach 90.5 miles in 22:52 before giving up. Because of all the additional bets, he would have won nearly $4,000 but failed.

Other opportunities arose for Weston to participate in 100-mile match races against others for large sums of money but he DNFed several competitions. In 1868, Upstate New York became the center for the 100-miler in both Troy and Buffalo, New York. In September 1868 on a half-mile track at Rensselear Park, a popular resort at that time in Troy, New York. Weston lost to Cornelius N. Payn (1847-1914 ) of Albany, New York, blaming his failure on the circular track which he was not used to walking on. Payn finished in 23:23:08. Other 100-mile races involving multiple walkers were conducted on that same Troy track that year.

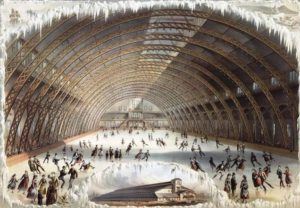

100-milers in indoor skating rinks

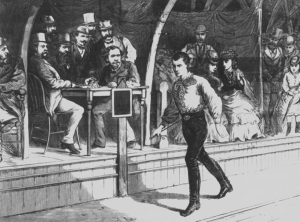

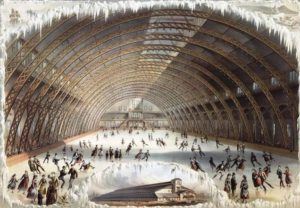

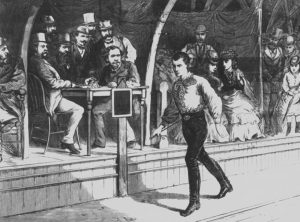

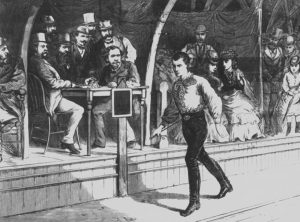

By the end of 1868, some 100-mile races started to be conducted indoors, in ice skating rinks. Race promoters realized that they could charge for the admission of spectators and put on great shows to induce hundreds to come and watch the spectacle of these distance races going in circles. The structures were engineered to pull in cold, outside air along the ice surface, while retaining some warmer air above. More often, it resulted in slushy ice. Converting skating rinks into walking tracks proved to be successful venues.

Cornelius Payn quickly became a very prolific 100-miler, competing at the distance multiple times within just a few weeks. He was 22 years old, about 5 feet 8 inches, 123 pounds, and described as “a lithe, wiry, well-formed unassuming, intelligent young man.” In November 1868 he took his efforts indoor during a cold month in Buffalo, New York to the skating rink there. “The track was about three feet in width, covered with tan-bark, and the foothold was not the best.” He finished in 22:30, resting three and half hours along the way. If the walkers could figure out how to greatly reduce their stoppage time, they could bring down their times significantly.

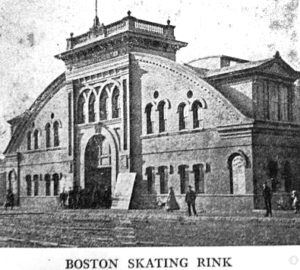

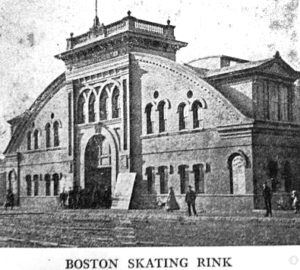

Boston also opened its new skating rink in 1869 to the 100-milers. The rink was located on Tremont Street and boasted the ability to accommodate 5,000 people, including skaters and spectators. It was said to include “warm and comfortable rooms, where polite attendants could always be found to assist in putting on skates.” A restaurant, like a skybox was fronted entirely of glass and offed a “fine view of the ice surface, and of the entire audience.” It was an amazing venue for a 100-mile match where Young McEttrick of Roxbury, Massachusetts walked 100 miles in 21:01.

In 1868, New York City also opened its massive indoor “Empire Skating Rink.” It was 350 feet long, 170 feet wide, and 70 feet high. The ice bed was 200 by 130 feet. The structure included a raised platform for spectators and could seat 10,000 people. At its grand opening, 3,000 skaters visited the rink. This venue was the site of many 100-mile competitions. Other skating rinks used for 100-milers included Newark, New Jersey and Syracuse, New York.

Fast 100s

In October 1868, Weston walked 100 miles on the road from Rye Station to White Plains, New York and claimed to set a world best 100-mile time of 22:19:08. At the finish, a large crowd gathered and he made a short victory speech. “The walk was made with little difficulty with no apparent ill effects afterward.” Was it really a world best? Communication about records was of course difficult in that era. Edward Rayner’s 17:52 time set in 1824 was still the fastest known 100-mile time at that point. In more recent times, on March 23, 1867, E. Thomas, “The Northern Deer” was reported to walk 100 miles in less than 21 hours at the Royal Park Grounds in Blackburn, England.

The back and forth 100-mile race

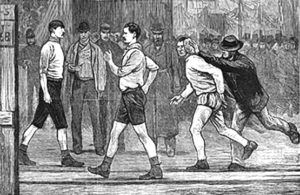

Before the start, Payn objected to the start in Fredonia, on a summit of a steep hill and did not want to have to climb back up it over and over again. He also complained about the rainy day which he felt would give Weston the advantage. Race officials overruled his objections.

This historic 100-mile race began at 2 p.m. on the challenging road and in torrents of rain. Payn reached five miles in just 56:30. Weston reached that distance in an hour flat. It was reported, “All along the line of the road were scattered horse carriages filled with eager spectators, and each house poured out its last inmate to see the men go by.”

Payne had a 23-minute lead when he completed the first 25-mile lap back at Fredonia in 4:59. The 100-mile race had captivated the town. “Here the anxious ones were thronged in the street, in the windows of houses, and on the steps of the hotel. As the white cap of Payn came in sight, speculation began as to whether it was Payn or not, and when this became a certainty, many a jaw dropped.”

But during the next 25-mile lap, Weston caught up and took the lead because Payn rested for 17 minutes. When Weston finished the second lap in 6:52 with the lead, he was greeted with “tumultuous cheers.” Payne was 16 minutes behind and Weston greeted him as the two passed by each other as he was on his third lap.

They continued on through the night. On the last 25-mile lap, Weston rested for nine minutes and only had a seven minute lead at mile 86. He looked weary when he made his last visit to Silver Lake at the turnaround, at 9:44 a.m. At mile 89, Payne caught up and went ahead because Weston was resting, laid out on a sofa in someone’s house, covered in blankets at the 20-hour mark. He had been having chest pains and was examined by doctors who feared that he was having heart problems. They said it was “sure death” to attempt the remaining distance. Weston quit the race at that point, another DNF against Payn.

Payn continue on in terrible weather “with the wind throwing all it could at him in the form of sleet and rain.” When he reached the 100-mile finish at Fredonia, the town folk were in disbelief that he had beaten Weston, who they thought was far superior. Payne still received cheers and finished in 22:52. Weston was very impressed with Payn’s accomplishment given the difficult course in such terrible weather.

Brutality in 100 milers

Reporters were horrified to see the number of spectators who came out hoping to watch brutal spectacles. The exhibitions were compared to people of old who caused their slaves to become purposely drunk in order to put on wretched displays in their intoxicated conditions.

Another reporter wrote in Buffalo, New York, where that city was a center for Pedestrianism, “The laws of this State prohibit cruelty to animals, yet the worst torture that can be inflicted on dumb brutes can scarcely equal that involved in a worse than useless walking match. Though self-imposed, the task ceases to be voluntary when once entered upon. Trainers and backers will hear to no complaints while physical power holds out but drive their victims about the track by a spur quite as effective and cruel as could be applied to a horse. It is brutality of the worst sort. Its result must be a lot of broken-down men, many of whom will doubtless find refuge ultimately in alms-houses.”

In 1871, Weston was again competing in a 100-mile match. It was reported, “The account of this achievement shows Weston to be a great donkey. On his ninety-third mile he got sleepy and had to be cow-hided and ice clamped to his head by his friends to keep him awake. Lemonade, beef tea and tonics were poured down his throat to keep him to time. He suffered terribly but held on. His pallid face, set teeth, blood-dilated nostrils, showed his distress. The men yelled and the women cackled at him encouragingly. Ammonia and whisky carried him through the last mile when he caved. Queer way, this, to make a living.”

Early Women 100-milers

As early as 1777, women also attempted to walk 100 miles in 24 hours. That year, a shepherd’s wife accepted a wager and started out on a course at Newmarket, England. A rich lady promised that if she succeeded, she would receive a salary for life of 50 guinea per year. It is unknown if the shepherd’s wife was successful.

Mrs. Harry Thomas

Writers in the newspapers were frequently rude when it was reported that a woman was trying to walk 100 miles. When Mrs. Harry Thomas attempted 100 miles in 24 hours in 1868, near St. Louis, Missouri, it was written, “The remarkable feature of the performance was that the dame was not to talk.” They would also comment on their appearance. “Mrs. Thomas is a rather small built woman, and would be considered rather good looking. She does not look to be very strongly made, nor capable of the fatigue of such a journey.”

Thomas performed her walk in Concordia Park. A broad plank was laid on a trestle or framework on which she walked back and forth. “Quite a large crowd of spectators assembled at the park to see the start. With an elastic, buoyant step, Mrs. Thomas began her tedious march at 1 p.m.” By night, she had slowed but continued without complaint. Watchers were left with her and furnished her the refreshments required and kept a record of the time and distance as each hour rolled by.

By morning she looked very fresh although her legs had swelled up and her steps were slower. At 23.5 hours she reached mile 92. “It being fully apparent that the remaining eight miles could not be made up in the concluding half hour, she ceased her walking amid the cheers and compliments of all bystanders.” She vowed to try again in a few weeks.

Madame Moore

A woman joined in the 100-mile frenzy that was taking place in America. Anne Fitzgibbons, a.k.a. “Madame Moore,” age 22, was a female pedestrian, clogger, and actress from England who had accomplished the “Barclay Match” of 1,000 miles in 1,000 hours at Manchester, England.

In 1868 she was being trained by Cornelius Payn’s trainer for a walking match at the Rensselaer Park in Troy, New York. The male press was not impressed and criticized her for wearing “male attire.” She soon walked 50 miles in 10:15:25 and then had her sights on 100 miles in 24 hours.

![]()

![]()

It was reported, “She came into court to settle damages. She stated that she had been engaged in the walking business for six months, and this was the first time she had been arrested. She said all her dresses were in a trunk at Troy, New York, and she had no change with her. The Squire told her she would be supplied at the penitentiary where he would send her for sixty days. She wore blue pantaloons and vest, checked shirt, sack coat, jockey hat, and her neck was tastily dressed with a stand-up paper collar and fashionable necktie. Her hair was cut short and combed behind her ears.”

She boasted at her court hearing that she could beat Weston in a race. At her sentencing she agreed to reform and her sentence was suspended. A month later she was in Buffalo, New York, the city that was friendly to Pedestrians. She was licensed by city officials to wear male attire during her walking exercises.

Sadly a couple months later, it was announced that Moore had died in Chittenango, New York, “from the result of over-exercise.” The press seemed to delight at the news, commenting about her male attire and that she had gone around in bad company.

However, a correction was quickly published, “We are happy to state she is yet in the land of the living, and astonishing the good people of Oneida, New York, with exhibitions of tall walking.”

The next month, In April 1869, Moore walked 100 miles inside a hall in West Troy, New York. with a time of 24 hours. “Besides knocking down a West Troy man who insisted on accompanying her in her perambulations. The Madame’s fighting weight is 150 pounds.” Moore soon issued challenges to Weston and any other man to a 100-mile race.

Weston in the Empire Skating Rink

In May 1870, Weston attempted to walk 100 miles in under 22 hours inside the massive Empire Skating Rink in New York City. Many people were still skeptical of his abilities and thought he was a fraud. W. W. Wallace, the proprietor of the rink wanted the city to make up their own minds and invited Weston to perform in front of a huge crowd.

The track laid out for him was three foot four inches wide in a circuit of 735 feet, requiring 717+ loops to reach 100 miles. Seven men served as judges in shifts. Weston was very confident and said he would accomplish his 100-mile task or “die in the attempt.” He reached 50 miles in 10:35, on target, and finished in 21:38:15, making only nine stops, all less than ten minutes.

More than 5,000 spectators witnessed his finish. “The announcement of the result was the signal of a deafening burst of applause from the thousands who had assembled to witness the successful termination of the greatest pedestrian feat ever attempted. Mr. Weston did not seem in the least fatigued, stepping off as briskly on the last mile as on the first, and after the one hundredth mile had been accomplished, he addressed the crowd from the judge’s stand, saying that it was love, not money, which had induced him to attempt the feat which he had just accomplished. It was the desire to free himself from the reputation which had been given to him by some of the daily papers of this city of being a ‘humbug,’ and to set right before the public those who had befriended and defended him.”

In trying to visualize the thousands of spectators cheering his finish, my memory goes back to an early morning in 2010, when for the first time, I finished 100 miles in less than 20 hours, almost two hours faster than Weston. There were no cheers. No one noticed. As I went past the timer tent, I called out to the man inside that I had just reached 100 miles. He gave a tired wave in response with no fanfare.

That match never happened, but a year later, Weston again competed in the skating rink and reached 100 miles in 21:01. In 1873, Smith did finish 100 miles in 22:33 at Belle City Hall in Wisconsin. He falsely claimed that his 100-mile time was the fastest time ever accomplished.

Entertainment

As early as 1828, an 18-year-old, William Bercley of Yorkshire, England, put on a show walking 100 miles in 24 hours and walked every other mile backwards. The course was purposely set up to go back and forth through the town of Bromley, England every mile, giving him great attention.

Bands frequently were at the 100-mile races. When Professor Sweet walked 100 miles in 22:57 in New Haven, Connecticut in 1868, “During the last half hour the band accompanied Mr. Sweet about the track, playing lively music to keep his spirits up, and sherry with eggs were given him for the same purpose.”

The true attraction to watch 100-milers was to view a reality show of pain. “Instead of being like the ball match or even the horse race, it becomes a trial of physical powers, like the prize-fight, in which the agony of the participants forms the chief attraction to the public.” It was thought that watching these painful spectacles would have absolutely no influence in encouraging “a sedentary and well-fed populations to take to their legs for exercise.”

Continued 100-mile frenzy

By the mid-1870s, the 100-mile frenzy was still in full operation in America. More and more walkers took up challenges to reach the milestone. It is estimated that by 1875, more than 100 people, both professional and amateur, had accomplished the sub-24-hour 100-miler in races or solo challenges. The 100-mile frenzy would get even more intense in the coming years.

Note, that these very early sub-24-hour walkers were not technically racewalker “Centurions.” That classification came to be in 1911, was only for amateurs, and they had to do the walk with strict racewalking rules in judged events. Most of these very early 100-mile walkers just walked free-form.

The parts of this 100-mile series:

- 54: Part 1 (1737-1875) Edward Payson Weston

- 55: Part 2 (1874-1878) Women Pedestrians

- 56: Part 3 (1879-1899) 100 Miles Craze

- 57: Part 4 (1900-1919) 100-Mile Records Fall

- 58: Part 5 (1902-1926) London to Brighton and Back

- 59: Part 6 (1927-1934) Arthur Newton

- 60: Part 7 (1930-1950) 100-Milers During the War

- 61: Part 8 (1950-1960) Wally Hayward and Ron Hopcroft

- 62: Part 9 (1961-1968) First Death Valley 100s

- 63: Part 10 (1968-1968) 1969 Walton-on-Thames 100

- 64: Part 11 (1970-1971) Women run 100-milers

- 65: Part 12 (1971-1973) Ron Bentley and Ted Corbitt

- 66: Part 13 (1974-1975) Gordy Ainsleigh

- 67: Part 14 (1975-1976) Cavin Woodward and Tom Osler

- 68: Part 15 (1975-1976) Andy West

- 69: Part 16 (1976-1977) Max Telford and Alan Jones

- 70: Part 17 (1973-1978) Badwater Roots

- 71: Part 18 (1977) Western States 100

- 72: Part 19 (1977) Don Ritchie World Record

- 73: Part 20 (1978-1979) The Unisphere 100

- 74: Part 21 (1978) Ed Dodd and Don Choi

- 75: Part 22 (1978) Fort Mead 100

- 76: Part 23 (1983) The 24-Hour Two-Man Relay

- 77: Part 24 (1978-1979) Alan Price – Ultrawalker

- 79: Part 25 (1978-1984) Early Hawaii 100-milers

- 81: Part 26 (1978) The 1978 Western States 100

- 87: Part 27 (1979) The Old Dominion 100

Sources

- The Ipswich Journal (England), Aug 21, 1762, Dec 30, 1876

- The Derby Mercury (England), Nov 10, 1737, Dec 24, 1773, Jun 12, 1788, Apr 21, 1824

- Liverpool Mercury (England), Apr 23, 1824

- The Evening Post (New York City, New York), Jun 8, 1824

- The Yorkshire Herald (England), Nov 29, 1828

- The Leeds Intelligencer and Yorkshire General Advertiser (England), Apr 22, 1793

- The Sun (New York, New York), May 28, 1870

- Public Ledger (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), Oct 25, 1837

- The Guard (Holy Springs, Mississippi), Oct 11, 1842

- The Era (London, England), Jun 6, 1847, Feb 26, 1860

- The Exeter Flying Post, Feb 22, 1860

- The Hampshire Advertiser (England), Sep 7, 1861, Jan 4, 1862

- Sioux City Journal (Iowa), Mar 16, 1867

- The Times (London, England), Dec 13, 1867

- The Burlington Free Press (Vermont), Nov 27, 1867

- The Daily Milwaukee News (Wisconsin), Aug 31, 1867

- Leavenworth Daily (Kansas), Apr 8, 1868

- The Titusville Herald (Pennsylvania), Nov 26, 1867

- S. Marshall, King of the Peds

- Raftsman’s Journal (Clearfield, Pennsylvania), Apr 22, 1868

- Star Tribune (Minneapolis, Minnesota), Apr 23, 1868

- The Philadelphia Inquirer (Pennsylvania), Jul 27, 1868

- The Louisville Daily Courier (Kentucky), Jul 6, 1868

- Russell Field, Playing for Change: The Continuing Struggle for Sport and Recreation

- New York Daily Herald, May 22, 1870

- Wayne Country Herald (Pennsylvania), Dec 15, 1870

- Buffalo Morning Express (New York), Sep 29, 1879

- Buffalo Courier (New York), Oct 12, 1868, Mar 15, 1869

- Chicago Tribune (Illinois), Apr 8, 1869

- The New North-West (Deer Lodge, Montana), Apr 13, 1872

- The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Oct 27, 1868

- The Tennessean (Nashville), Nov 15, 1868

- The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (New York), Nov, 20, 1868, Dec 15, 1868

- Buffalo Evening Post (New York), Apr 21, 1869

- The Atlanta Constitution (Georgia), Oct 22, 1871

- Wisconsin State Journal (Madison, Wisconsin), Dec 5, 1873

- The Rutland Daily Globe (Vermont), Mar 5, 1875