Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 26:50 — 31.5MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

You can read, listen, or watch

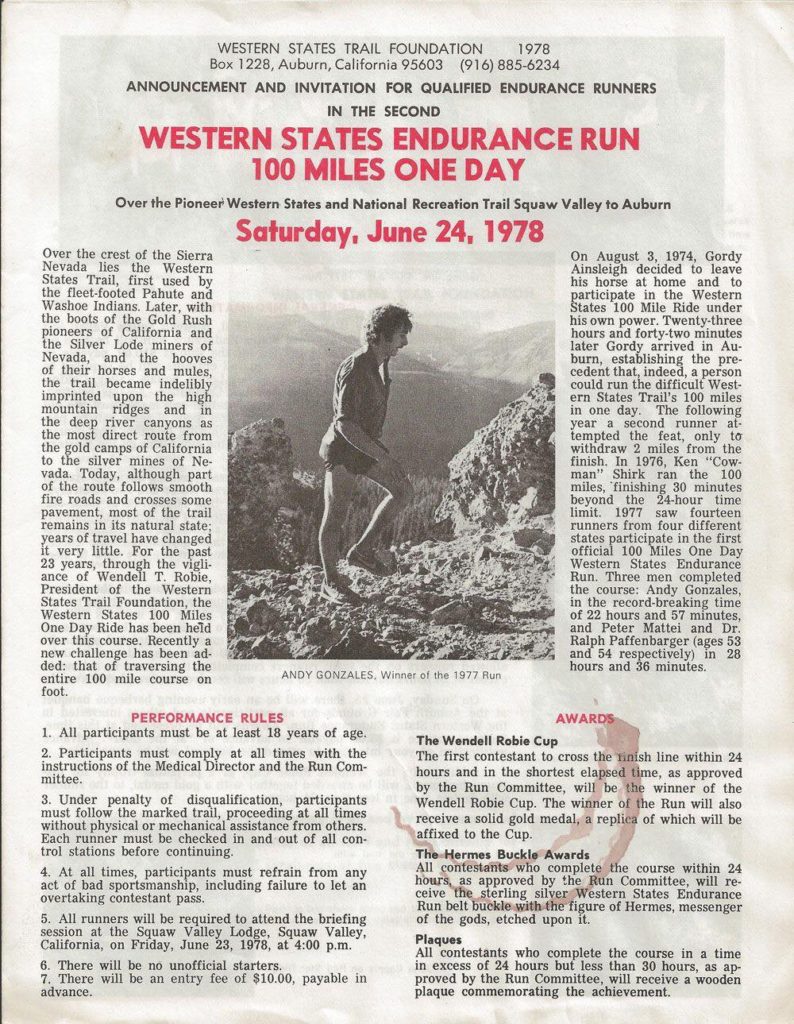

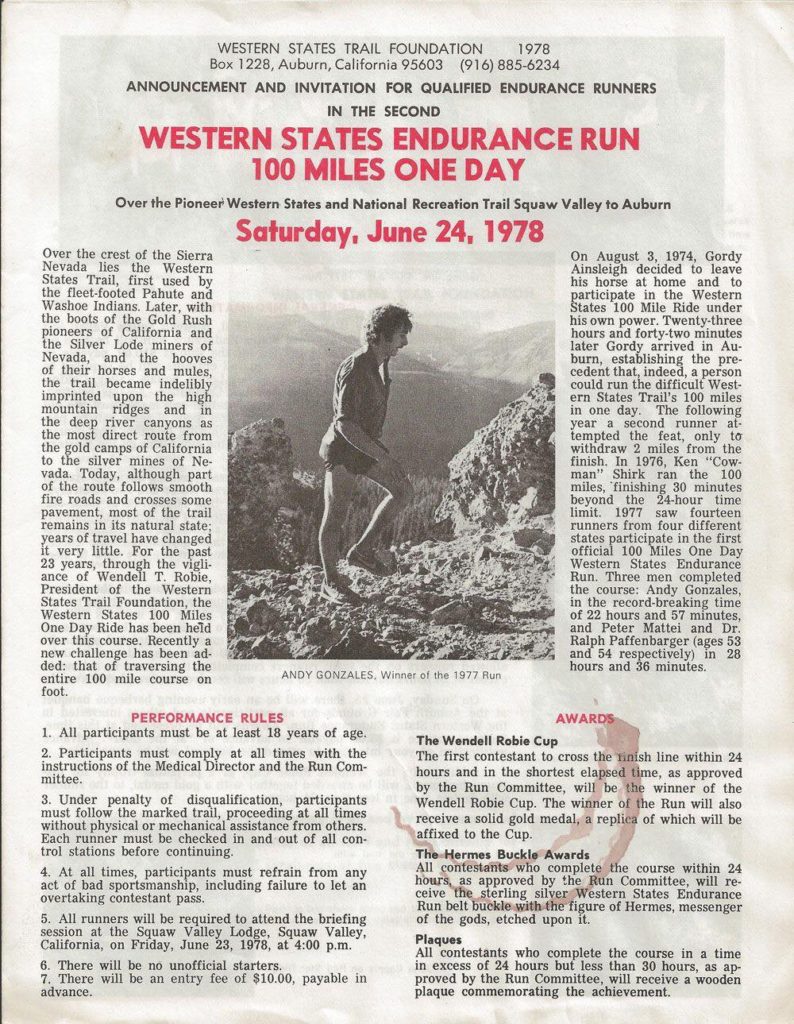

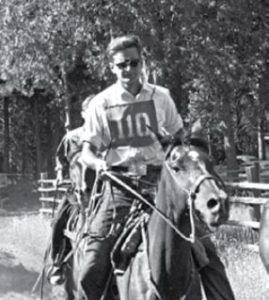

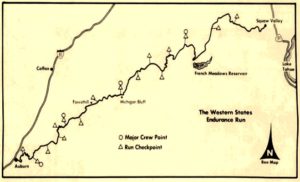

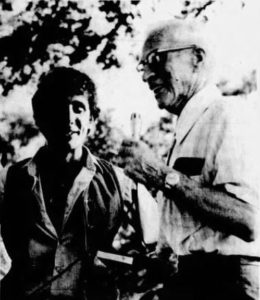

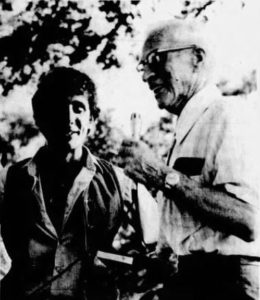

The 1978 Western States 100 was the second year the race was held. Six years earlier, seven soldiers from Fort Riley Kansas proved that the horse trail could be conquered on foot, and they were awarded with the “First Finishers on Foot” trophy by Western States founder, Wendell Robie (1895-1984). Two years later, in 1974, Gordy Ainsleigh surprised his horse endurance peers when he ran the 89-mile Western States Trail in less than 24 hours.

The 1978 Western States 100 was the second year the race was held. Six years earlier, seven soldiers from Fort Riley Kansas proved that the horse trail could be conquered on foot, and they were awarded with the “First Finishers on Foot” trophy by Western States founder, Wendell Robie (1895-1984). Two years later, in 1974, Gordy Ainsleigh surprised his horse endurance peers when he ran the 89-mile Western States Trail in less than 24 hours.

Three years later, in 1977, Robie decided it was time to organize a foot race on his trail. The inaugural race was hastily put together by a few volunteers who had horse endurance race experience but did not have much experience with human running races (see episode 71). The first race was mostly self-supported and fairly dangerous in very high temperatures. They were lucky that there were no serious heat-related emergencies, and only three of the 16 starters finished.

Planning for the 1978 Western States 100 Run became more serious and was much better organized. The 1978 race should be considered as the first fully supported Western States Endurance Run which gave all entrants a good chance to finish.

|

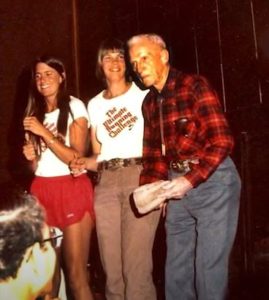

A Western States Endurance Run Board of Governors was formally organized by race founder, Wendall Robie. The four members, affectionately called “The Gang of Four,” were all horse endurance riders, still learning what ultrarunning was all about. They were Phillip (1944-) and Shannon Gardner (1947-), and Curtis (1949-) and Marion “Mo” Sproul (1952-). Curt served as the president. Even though they still had much to learn about the running sport, they blazed ahead into history to put together a mountain ultra that many other key ultras would mimic. Joe Sloan, age 44, an experienced runner and public relations specialist from Auburn who ran in the Boston Marathon that year claimed that he was also on the new Board of Governors that year.

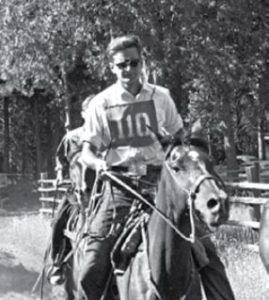

Because of difficulties experienced in 1977 with both runners and horses on the same trail, especially with single-track sections, the run was moved to the month before the Tevis Cup (Western States Trail Ride), on June 24, 1978. Shannon Gardner worked at Robie’s bank, Heart Federal Savings and Loan, made contacts to get the word out, and fielded calls from interested runners.

Marketing Western States 100

![]()

![]()

The 1978 entry form warned, “Do not enter unless in excellent physical condition, have run marathon distances over 26 miles, and have had a complete physical examination, preferably including a stress electrocardiogram.”

The race organizers started to prop up the legend of Gordy Ainsleigh and numerous news articles erroneously stated that he was the first to cover the course on foot. They purposely decided to make no mention of the soldiers from Fort Riley, Kansas who completed the course on foot during the Tevis Cup in 1972 and were given the “First Finisher on Foot” trophy from Wendell Robie. Instead Ainsleigh, one of their own, would be given all the credit as being the first finisher.

Planning for the Race

The 1978 race included some performance rules. Without an understanding of the existing cooperative culture in ultrarunning, one rule was: “At all times, participants must refrain from any act of bad sportsmanship, including failure to let an overtaking contestant pass.” The race staff tried hard to be well-prepared but admitted that it was still “thrown together” with the hope that it would succeed that year. They still had not made any attempts to measure the course, just trusting that it was about 100 miles. It was far from that distance. The 1977-79 course stood at 89 miles.

Mo Sproul and Shannon Gardner served as co-race directors. They became collectively known as “Mo-Shan.” Years later, John Trent (1963-) who became the run board’s president said of Mo, “Without her presence, along with a couple of other people at a key juncture in the late 1970s, Western States wouldn’t exist. So much of who we are, especially the spirit, and how we try to find common ground as a board, has to do with Mo.”

Mo got involved with the run during the previous year, 1977. She explained, “Wendell Robie called and said, ‘Would you please come be a timer for these runners who are running with the horses?’ I said, ‘No, it’s too hot, I’m not driving around after a bunch of runners.’ Finally, I broke down and said yes. So, we shot the gun off at the start, and then I followed all the way along with Bob Lind, our doctor, who was looking after the runners and trying to keep track of medical data. I became completely fascinated by what the runners ate, what they were trying to do and how their weight changed. That’s when I got really hooked on what it meant to run through those mountains in those conditions.”

Medical checks were again supervised by Dr. Bob Lind who was still learning about ultrarunners. Runners were told if they lost 10% of their weight they would be removed from the race. The finish line that year was at the Placer High School Track because the fair was being held at the fairgrounds. The weather for the 1978 race was mild, but there was significant deep snow in the high country to run over, fifteen miles of it.

The Runners

There were 63 starters, including five women. The California media highlighted some of these runners before the race.

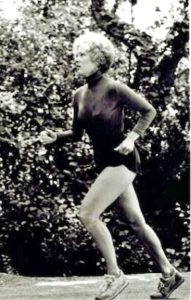

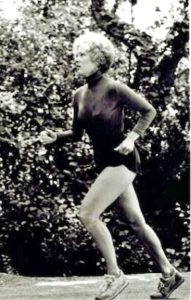

Pat Smythe (1943-) and Mary Healy of Napa, California, were co-leaders of “Women on the Run” based out of Kentfield, California. Smythe grew up in Vancouver, Washinton and started to run recreationally in college to lose weight. She said, “I wasn’t in it for competition. My running was something that was really personal.” While working as a secretary for a school district, she met Healy who had organized “Women on the Run” to teach the basics of running to women in the San Francisco Bay area. Together they taught classes.

Healy had experience running marathons and told Smythe about Western States. They did not know that many women had previously run 100 miles in ultras, but wanted to make a statement and said, “We believe that women can go the distance. Women have been running marathons for years.” Smythe and Healy started serious training five weeks before the race, going from 30 miles per week to 100 miles. Smythe was determined to finish. She recalled, “Mentally, I knew I was tough, and prior to the race, I believed that it was ultimately going to be this toughness, more than physical conditioning that was going to make or break it for me.”

Two eighteen-year-old twins were also among the starters, Karin and Peggy Stok (1960-), of Redwood City, California. They both had good experience running in 50-mile road races.

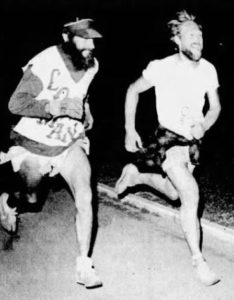

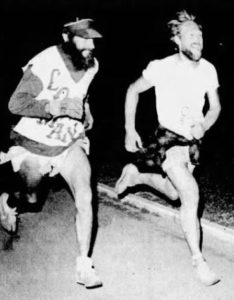

Ken “Cowman” Shirk (1944-), age 34, originally a farm boy from Salinas, California, had signed up to run again. He had accomplished a solo run on the Western States Trail in 1976 in 24:20, but DNFed the official 1977 race at about mile 48.

Gordy Ainsleigh (1947-), age 31, the emerging marketing icon of Western States was entered, looking for his first official ultra finish. He had been the eighth person to cover the Western States Trail on foot during the Tevis cup, the first to do in less than 24 hours. He admitted that he was not in his best physical condition for the 1978 race because he had not trained very much and said, “It takes three months of hard running to be in shape.”

He explained how he got into the race. “I had just moved out from New York. Our marketing director was a wonderful character named Phil Lenihan. He was also a runner. I was sitting in my office one day and heard running footsteps coming down the corridor, shouting, “Doug, Doug.” It was Phil. He had just been in the back room with the editorial staff, and he had proofs of the next issue of Runner’s World. He said, “Doug, look at this!” He showed me a spread of Redstar Ridge with two horses and two runners on it from the 1977 Western States Run. Phil said, “Doug, we’ve got to do this!.” I had to admit that it looked really exciting, but I questioned, “100 miles in the Sierras?” I didn’t think anything more about it. Two weeks later Phil came running down to my office and said, “Doug, I entered us both.”

The Start

Gonzales and Howard took the early lead. They climbed up and over the snow above Squaw Valley together. Later, Howard pushed on ahead. Gonzales was dressed very skimpy. He took a pair of running shorts and cut off the outer layer looking like he ran in a speedo. He had neglected to bring his best running shoe and the tread was worn on his shoes, so Shannon Gardner gave him her shoes to run in which were the same size.

The first aid station was at Red Star Ridge in deep snow. Wendell Robie was there wearing hip boots with a snowmobile and a bucket of water with a ladle that all runners shared.

Near Michigan Bluff, Gonzales caught up to Howard who was laying by the side of the trail suffering. Gonzales offered help, but Howard declined, was surprised and bit in awe of Gonzales’ ability to catch up to him. They later ran together for a while, building up a huge lead, but both got lost during the night for a significant amount of time. The trail was still poorly marked in places

It was reported, “The trail went through snow, dirt, shale, loose rocks and the talcum powder Sierra dust that choked runners. They carried flashlights at night and forged the knee-high American River at dawn when the current was strong and the water cold.” Some of the runners were paced by horseback riders.

Healy dropped out at Robinson Flat (mile 30) due to altitude sickness. Smythe and Lenihan ran on but had slowed to a pace that aid station volunteers thought would not allow them to make it to Auburn in time. Lenihan, confident, replied, “Radio ahead and have our plaques ready for us.” As Smythe ran along, an old miner on the course approached her and said, “I’ve heard about you. I’ve got something for you.” He then gave her a little gold nugget. Smythe planned to make it into a pendant.

The mild temperatures that year really helped the runners. Lind said, “We were pretty lucky. We didn’t have any serious mishaps during the run. I really had a lot of fears about taking this one on. It was so enticing though, I couldn’t pass it by. These are some of the nicest people I’ve ever been associated with in an athletic event, they can’t do enough for you. There is a great deal of harmony and closeness.” Lind and his medical staff learned more that year about how ultrarunning affects the body. “His group discovered, among other things, that oral temperature readings often indicate hypothermia, the drop of the runner’s temperature below normal, when in fact the core or body temperature is normal. Some NASA technicians came and ran some blood test on volunteer runners

![]()

![]()

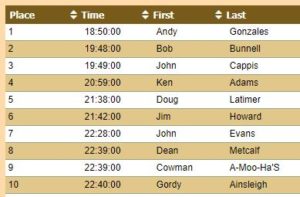

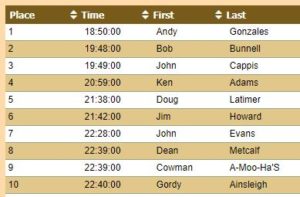

Bob Bunnell of San Rafael finished second in 19:48, and John Cappis, of Las Alamos, New Mexico, finished third in 19:49, avenging his 1977 68-mile DNF. Cappis said, “You have to be in superior condition to even think about running Western States. Anybody that finishes is a winner.” Doug Latimer finished 5th with 21:38, and Jim Howard finished sixth with 21:42.

Legends Ralph Paffenbarger, age 55, of Berkeley, California, and Peter Mattei, age 54, of Alamo, California who had teamed up to finish in 1977 in 28:36, came in together in 23:29, improving their best time. Dave Niederhaus, the marine who DNFed in 1977 finished in 26:26.

![]()

![]()

1978 Western States turned out to be Smythe’s last competitive running finish as she stopped running in 1982. Four decades later, she reflected, “It’s always just been a real personal thing, a real quiet thing that has stayed with me. I’m grateful that I was able to do it and love my body for its effort in pulling through for me.”

The Final Finishers

Steve Mason (1948-) age 30, of Reno, Nevada, lost the trail the trail at 3 a.m. with only nine miles to go and probably would have finished in under 24 hours. He became lost for nearly six hours, stranded on a cliff above the American River. As soon as race officials realized that he was missing, Search and Rescue from both El Dorado and Placer Counties were called out and started combing the hills for him.

His wife, Jane Mason was greatly worried. She reported, “Steve was found after almost six hours by some young people on horseback, who alerted the rescue team. Fortunately, he was not injured beyond a little hunger and thirst.” Mason was escorted back to “civilization” and examined by Dr. Lind who pronounced that he was in decent shape to finish the race if he wanted. His wife, expressing much appreciation, shared the good news, “With the help of John Kessler, who donned his track shoes and paced Steve the last miles of the race, my husband was able to finish within the 30 hours (29:38) and experience the feeling of accomplishing something for which he had trained for months.” Lind said Mason turned tragedy into triumph.

Eighteen-year-old twins Peggy and Karin Stok also got lost at about mile 92. Peggy said, “You get what’s called runner’s daze. The rocks looked like they were playing a movie and I clearly heard the river talking.” They were eventually found by some campers who led them out of the woods and they arrived at Auburn in 37 hours but were not listed in results for some reason.

Among those who did not finish but dared to try were Michael Garrett, Dan Marus, Marc Askew, Jeff Sawyer, Bob Suter, David Berry, Jim Larimer, Gordon Bertoglio, Jim Weil, Tony Stratta, Mary Healy, Skip Swannack, Dan Hounchell, Dennis Gustafson, and Curt Sproul.

Reports about the 1978 Western States 100 were pretty much limited to Northern California newspapers. But mainstream ultrarunning did take notice as a paragraph was included in Nick Marshall’s 1978 Ultra Distance Summary. The Unisphere 100 was held the same weekend at Flushing Meadows in New York City.

Marshall reported about the California race, “Numerous horror stories about the extremely rugged conditions facing them on the uncertified point-to-point course through the Sierra Nevada had served to whet the appetites of the adventuresome souls. When the dust cleared, literally and figuratively, the next day in Auburn, defending champ Andy Gonzales’ 18:51 had lopped an incredible four hours from his course record set the previous year.” He went on to recognize it as “the most difficult run in America.”

At the finish, Shannon Gardner said that the finishers looked “brutalized,” but the race that year was a huge success. Robie was ecstatic and told Gardner that they had “caught a bear by the tail.” He knew the race would become a very big deal. It was proclaimed that with both the ride and the run, that Auburn was “the endurance capital of the world.”

Mo Sproul added, “It was fun to organize, fun to see the growing enthusiasm and fun to see Wendell’s interest in it. Wendell and his administrative assistant, Drucilla Barner, were encouraging Shannon and me to help this event grow. It was their enthusiasm combined with ours that launched it.”

The Run did take off. Other mountain trail 100 race organizers soon contacted Shannon Gardner, including Old Dominion and Wasatch Front, to pick her brain about organizing and conducting trail 100s.

The parts of this 100-mile series:

- 54: Part 1 (1737-1875) Edward Payson Weston

- 55: Part 2 (1874-1878) Women Pedestrians

- 56: Part 3 (1879-1899) 100 Miles Craze

- 57: Part 4 (1900-1919) 100-Mile Records Fall

- 58: Part 5 (1902-1926) London to Brighton and Back

- 59: Part 6 (1927-1934) Arthur Newton

- 60: Part 7 (1930-1950) 100-Milers During the War

- 61: Part 8 (1950-1960) Wally Hayward and Ron Hopcroft

- 62: Part 9 (1961-1968) First Death Valley 100s

- 63: Part 10 (1968-1968) 1969 Walton-on-Thames 100

- 64: Part 11 (1970-1971) Women run 100-milers

- 65: Part 12 (1971-1973) Ron Bentley and Ted Corbitt

- 66: Part 13 (1974-1975) Gordy Ainsleigh

- 67: Part 14 (1975-1976) Cavin Woodward and Tom Osler

- 68: Part 15 (1975-1976) Andy West

- 69: Part 16 (1976-1977) Max Telford and Alan Jones

- 70: Part 17 (1973-1978) Badwater Roots

- 71: Part 18 (1977) Western States 100

- 72: Part 19 (1977) Don Ritchie World Record

- 73: Part 20 (1978-1979) The Unisphere 100

- 74: Part 21 (1978) Ed Dodd and Don Choi

- 75: Part 22 (1978) Fort Mead 100

- 76: Part 23 (1983) The 24-Hour Two-Man Relay

- 77: Part 24 (1978-1979) Alan Price – Ultrawalker

- 79: Part 25 (1978-1984) Early Hawaii 100-milers

- 81: Part 26 (1978) The 1978 Western States 100

- 87: Part 27 (1979) The Old Dominion 100

Sources:

- Hattiesburg American, Jul 30, 1978

- The Berkeley Gazette (California), Jun 27, 1978

- Sacramento Bee (California), Jun 14, 24 28, 1978

- The Chico Enterprise-Record (California), Jun 28, 1978

- The Napa Valley Register (California), Jun 22, 27 1978

- The San Francisco Examiner (California), May 2, 1979

- Auburn Journal (California) Apr 17, Jun 19, 23, 28, Jul 14, 1978, May 4, Jun 18, Jul 11,13, 1979,

- The Press-Tribune (Roseville, California), Jun 23,29, 1978

- The Pacer Herald (Rocklin, California), Jul 12, 1979

- The Los Angeles Times, Jul 13, 1979

- Nick Marshall, Ultradistance Summary, 1978

- 2021 Interview with Andy Gonzales

- 2017 interview with Shannon Yewell Weil, Western States 100-Mile Endurance Run and Trustee for 30 years.

- Runners World, “How the First Women’s Champion of Western States Found Independence on the Trail.”

- Trail Runner, “How Western States Became a Race”

- 2014 Western States history presentation by Shannon Yewell Weil at the 2014 Western States Training Weekend. This Will Never Catch On: The birth of an Icon