Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 27:18 — 30.0MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

This part will cover additional stories found through deeper research, adding to the history shared in found in the new book, Grand Canyon Rim to Rim History.

Overcrowding Concerns

In 1971, because of overcrowding in the inner Canyon, the Park Service started to implement a reservation system for camping. They shared a situation on the Easter weekend when 800 people tried to camp at Phantom Ranch, which only handled 75. Park Superintendent Robert Lovegren (1926-2010), said, “We readily accept quotas on tickets to a theater or sports event. If the performance is sold out, we wait for the next one or the next season. We don’t insist on crowding in to sit on someone’s lap.” Reservations requests were made by mail. In the first month of the system, 1,463 people wanted to reserve 100 camping spots for Easter weekend. They used a lottery system for that weekend.

| Get Davy Crockett’s new book, Grand Canyon Rim to Rim History. Read more than a century of the history of crossing the Grand Canyon Rim to Rim. 295 pages, 400+ photos. Paperback, hardcover, Kindle, and Audible. |

Phantom Ranch Chef

1971 Flood Damage

The washout exposed a 60-foot section of the new trans-canyon water line about a mile above Phantom Ranch. Major breakage points required tools and a giant welder to be brought in by helicopter. The North Kaibab Trail was closed for more than a week to make repairs. Then just a month later, a two-hour storm dumped 1.34 inches on the South Rim and washed out a portion of Bright Angel Trail near Indian Garden and left an inch of water in the Ranger Cabin. Thirty hikers had to go across the Tonto Trail and exit using the Kaibab Trail.

Grand Canyon Noise Pollution

Hump to Hole Attempt

Runaway From Inner Canyon

Concerns About Crowded Inner Canyon

The corridor campgrounds could only handle 205 people per night. About 73,000 hikers poured in and out of the Canyon in 1974. An electric-eye counter was installed at the trailhead of Bright Angel Trail. Park Superintendent Merle E. Stitt (1920-1980) announced on December 9, 1974, “No group of hikers may be larger than 15 persons.” Debates started taking place about whether the trails were too crowded with day hikers, overnight backpackers, and rim-to-rim hikers and runners. On the May opening weekend, it was estimated that 600 hikers used the Corridor trails. No runners were seen. It was asked, “How many people are too many people in the Grand Canyon?” This is still a question asked 50 years later.

One observer wrote, “It’s not uncommon to see parties lugging two-pound jars of peanut butter and gallon jugs of Kool Aide. They are totally oblivious to the fact that there are no trash cans and what goes down should, by all good conscience, come back up. On one hand, you have the people who lug in tents and down sleeping bags, which are totally unnecessary during summer. On the other, there are those whose entire food stash consists of a box of Cheerios. What these people do not realize is that the Grand Canyon is not a Sunday stroll.”

Bruce Aiken at Roaring Spring recalled on a day in June. “It was blazing hot. At least 100 degrees. And up the trail comes a guy with a long-sleeve white shirt, a tie, a long-sleeve black sweatshirt, pants and regular street shoes. And on his shoulders, he’s carrying a bundle that must have weighed 100 pounds and was six feet long. It was the entire set of the Encyclopedia Britannica.”

The Fragrance of Mules

During the summer of 1975, K.C. Cole made her way down and up Bright Angel Trail at the prompting of her husband. She wrote, “Bright Angel Trail is the easiest of dozens of trails in the canyon and the most heavily traveled by hikers and mule trains alike. It is also the most heavily deposited with mule droppings. And where one mule drops, all mules tend to drop, a custom fostered by muleskinners who stop periodically to yell, ‘Pitstop!’ The result is a stench that only hikers too breathless to hold their noses for the full length of the pit stop can fully appreciate. The mules and their droppings plagued our entire climb. But worse than the mules, were the happy hikers skipping down the trail, all of whom, undoubtedly, thought that hiking the Grand Canyon was a great idea. They must have, for they looked straight into my watering eyes, at my decrepit, exhausted and sopping body and cheerfully said, ‘Hi!’ I contented myself with visions of what these happy hikers would feel like on their journey out tomorrow.”

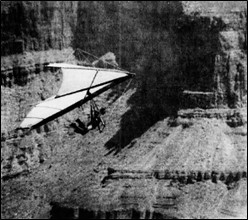

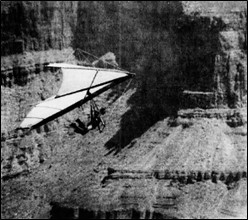

Five Hang-Glide into Canyon

Refurbishment of Phantom Ranch

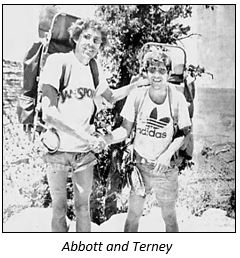

Rim to Rim using Old Bright Angel Trail

They reached the top of Bright Angel Canyon and started to descend carrying their 45-pound packs. Abbot wrote, “The old abandoned trail was hard to follow in places. It was dangerously steep along some cliff-side cut-outs. In some places the trail was not there at all, and was only marked by some long-ago trail blazer who had stacked several small stones on top of each other every 100 yards or so. The trail had poor footing in places, and darn if those places weren’t in the most precarious spots, on ledges that narrowed to two hiking boots wide. Some rockslides covered the trail. As we stepped over the rockslides, we tried not to teeter backward.”

Sewer Problems at Indian Garden

In July 1978, Indian Garden was closed to overnight camping because the sewer system had failed. Park Superintendent Merle Stitt explained, “Until we can design and construct the proper system we will install and use chemical toilets as an interim measure. This will require that the treated effluent be hauled out by helicopter.”

Balloonist Flies Rim to Rim

1980 Flash Flood

On September 9, 1980, a flash flood occurred affecting the trail. Rain and hailstorm deposited more than one inch of rain in less than 20 minutes and then it kept raining the rest of the day. There was substantial damage. Many sections of both the Bright Angel and North Kaibab trails were completely obliterated.

Park Superintendent Richard “Dick” Wakefield Marks (1935-2006) said, “The campground and water system at Indian Garden on the Bright Angel trail were washed out. Fortunately, the trans-canyon water pipeline remained intact as far as we can tell.” Bright Angel and North Kaibab trails were immediately closed, but the South Kaibab trail remained open. After two weeks of work, most of the trails were opened, but Bright Angel to Phantom Ranch was closed for nearly two months to hikers and another month to mules. Repair costs exceeded $120,000.

Wild Burros

Lost Hiker

To the shock of everyone, after six days in the inner Canyon, Fountain walked into Phantom Ranch at 7 a.m. He was reported to be a little hungry and tired, but was okay. Somehow, nearly 100 searchers had missed him. He had walked about 24 miles on the Tonto Trail to Tipoff and then headed down South Kaibab to Phantom Ranch. Authorities said, “In the last little distance of his hike, he met another hiker who called our dispatch office and said there was a fellow with him by the name of John Fountain who wanted to report his whereabouts.”

Fountain had traveled mostly at night, found shade when it was hot, and stayed two nights in one place. He said, “The first day was the worst because I was in the sun the whole day. After that, I tried to sleep during the day and hike in the morning and night, but I didn’t sleep much. The first night I was very frightened because I ran out of water. When I found some the next day, I wasn’t scared anymore.” He ate frog legs and found water each day in places where rangers didn’t know there was water. He lost about 20 pounds during the ordeal.

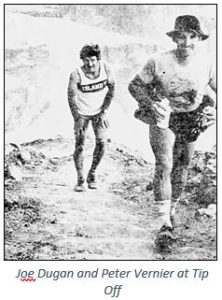

Double Crossings

In the 1980s, newspapers were highlighting double crossing successes with more frequency, causing increased interest in making attempts. In 1982, two men from New York City, Joe Dugan (1938-) and Pete Vernier, accomplished the double. “Bolder-than-average runners wanted to conquer the Grand Canyon by racing down one rim, across the Colorado River, up the other rim and then back down and up the other way. The 41.2-mile round-trip is known as the Grand Canyon Double.” Dugan said, “I was worried about getting lost. I once ran in a race in Central Park and got lost.” He compared the climb up to the North Rim, like climbing up the stairs of the Hyatt Hotel in New York City. “On the 50th floor, you look up and see you have 50 floors to go.” He finished in 10:12:48. “I had this goal since December. It’s like climbing Everest. I ran across the Grand Canyon.”

Donald Ray Cushman (1943-) of Mooresville, Indiana, a photographer for the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra, accomplished a solo double crossing in 24 hours in 1982. In the early 70s, he failed to accomplish three single-crossings because of the heat. “This time Don decided to hike in late afternoon, through the night. He felt confident he could maintain his 2-mile-an-hour pace along the steep trails.”

His double required careful planning because the Canteen at Phantom Ranch was closed due to flood damage. He succeeded. “I did what I had set out to do. Going across was devastating, coming back was exhilarating. I felt happy, very peaceful. It was the first time I’ve walked out of the canyon and been able to say, ‘I had fun today.’ I might have been crazy to try it, but I wanted it on my record.”

Starting in 1977, Bill Maxwell, an electronics technician for Honeywell-Sperry in Phoenix, Arizona, started leading groups each year to hike rim-to-rim and then hike back after a day of rest. 1987 was the eleventh year for Maxwell. Unlike other groups, Maxwell would secure permits with the park, make reservations with the lodge on the North Rim, and coordinate shuttles for those doing a single crossing. Each year, the group got larger. In 1986, there were 54 people in the group, the oldest 55, the youngest 10. “The hike is more of a fun trip than a competition. Everyone walks at his own pace and enjoys the scenery and companionship.” All members of his group always completed the hike. “Of course, some who complete the hike swear they’ll never do it again. But it wears off, and they remember all the good times. Next year they’re ready to do it again.”

Crowded Trails

In 1983, it was noticed that the inner Canyon corridor trails were getting crowded. “Once upon a time people hiked down Bright Angel or Kaibab Trail simply to enjoy a different perspective on the Canyon. Now the trails have become so busy they are virtual promenades. The Canyon experience today has more than a little in common with a California beach.” It was noted that one young hiker, carrying a heavy load, was playing “a very large, battery powered stereo, the kind of thing that is impolitely known as a ghetto blaster.” At Indian Garden, a young man sat on a picnic table playing the same tune on the harmonica repeatedly. An out-of-shape woman was seen going down the trail only carrying a styrofoam cup full of water, relying on other hikers to rescue her by filling the cup up along the way. Despite all of this, it was predicted, “The Canyon will endure it all.”

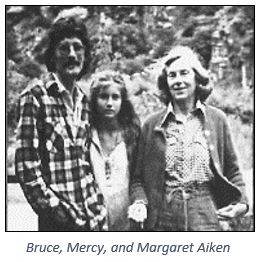

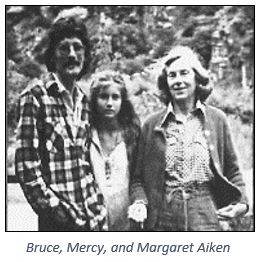

Visit with the Aikens

In 1985, Serrin Eudora Anderson (1939-) of Fort Lauderdale, Florida, agreed to give Margaret, an artist, a ride across the country from South Florida to the Grand Canyon. In exchange for the five-day drive, Margaret invited her to stay at her son’s house, down in the Canyon. The lady was Margaret (Davis) Aiken (1924-2003) and her son was Bruce Aiken (1950-), who maintained the pumps at Roaring Springs. (See chapter 15).

From the South Rim, Margaret took a helicopter ride to Roaring Springs and Anderson went on foot down into the Canyon from Yaki Point and reached Roaring Springs. “Margaret met me on the trail with her granddaughter Mercy, 13. They showed me broken pottery from Indian ruins I would never have noticed. They guided me through ‘the library’ where layered sandstone looks like stacks of books. Broken apart, stress lines on the rock look like ancient hieroglyphics”

Flights Over the Canyon

The first known tourist flight over the Grand Canyon occurred in February 1919. By 1985, there were about 48,000 tourist flights, ridden by 400,000 people each year over and through the Canyon, as low as 2,000 feet, bringing in $70 million to the tourism industry. Hikers and environmentalists banded together to protest the noise explosion over the Canyon, eliminating the peace and quiet that once was experienced in the inner Canyon. The Park Service initially avoided the controversy, although rangers called for a ban on flights. Grand Canyon Airlines general manager, Ronald Lee Warren (1947-) said, “The aircraft makes no impact on the canyon except for a temporary sound of one to three minutes. There is no residual damage.”

On June 18, 1986, a helicopter collided with a twin-engine plane, crashing in the inner canyon near Crystal Rapids, nine miles downriver from Bright Angel Trail. The tale of the plane was sheared off by the helicopter rotor. Both aircraft crashed and completely disintegrated. All 25 people onboard both of the aircraft died. Smoke billowed from down in the Canyon. A boatman on the river said, “I saw a flash in the sky, two bright lights and a puff of smoke that floated through the air.” Environmentalists said, “This underscores the dangers that we’ve learned about uncontrolled line-of-sight flying below the rim.” An executive of the helicopter company argued, “Somebody made a mistake, that’s all, a terrible mistake.” He argued that flying in the canyon was “remarkably safe.” He added, “I’m sure the Sierra Club will capitalize on this and try to stuff it down our throats.”

Arguments continued, and proposals were discussed. The Interior Department proposed a partial ban of sightseeing flights over the Canyon. The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) was the authority that could impose a ban and considered new safety proposals. Congress got into the fray and passed legislation banning flights below the rim. At the end of 1987, the National Park Service proposed flight-free zones above 44% of the Canyon. In March 1987, the FAA finally established a special flight rules area over the Canyon, moving aircraft away from noise sensitive areas. In the years to follow, the rules continued to be modified.

Shuttle Service Starts

In 1988, the landing strip first established by Emery Kolb in 1926 at the North Rim was shut down and tilled under by the FAA. Hikers who wanted to do a single crossing could no longer fly quickly to the other rim. Two rental car companies allowed cars to be dropped off at the North Rim for $150. In August 1989, Trans Canyon started to offer a daily shuttle service in each direction using a 15-passenger van. The price was $50 one-way, $85 round-trip. Running clubs around the country started to take advantage of the shuttle and organized rim-to-rim runs.

Also in 1989, plans were put in place to construct a new $5 million hotel with 100 rooms and a restaurant at the North Rim, which would have been nice for rim-to-rim hikers because of the very limited lodging on that rim. The Sierra Club filed suit in Federal Court and successfully blocked the plans.

Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim Series

- 46: Part 1 (1890-1928)

- 47: Part 2 (1928-1964)

- 48: Part 3 (1964-1972)

- 49: Part 4: Aiken Family

- 50: Part 5: The Races

- 135: Part 6: Early Guides

- 136: Part 7: Prof Cureton

- 137: Part 8: Kolb Brothers

- 138: Part 9: Phantom Ranch

- 139: Part 10: More on 1927-1949

- 141: Part 11: More on 1950-1964

- 143: Part 12: More on 1971-1989

- 144: Part 13: More on 1990-2020