Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 25:22 — 28.4MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett. You can read, listen, or watch

By Davy Crockett. You can read, listen, or watch

In 1906, David Dexter Rust (1874-1963) established a permanent camp near the confluence of Bright Angel Creek and the Colorado River that they name Rust Camp. They dug irrigation ditches and planted cottonwood trees by transplanting branches cut from trees found in nearby Phantom Creek. The camp was visited mostly by hunters going to and from the North Rim. Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919) visited the camp in 1913 for a few hours and it was renamed to Roosevelt Camp. By 1917, the government revoked the permit for the camp, and it became deserted. As the Grand Canyon National Park was established in 1919, funds became available to develop the park and its trails. Phantom Ranch, a Grand Canyon jewel was ready to be built.

In 1906, David Dexter Rust (1874-1963) established a permanent camp near the confluence of Bright Angel Creek and the Colorado River that they name Rust Camp. They dug irrigation ditches and planted cottonwood trees by transplanting branches cut from trees found in nearby Phantom Creek. The camp was visited mostly by hunters going to and from the North Rim. Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919) visited the camp in 1913 for a few hours and it was renamed to Roosevelt Camp. By 1917, the government revoked the permit for the camp, and it became deserted. As the Grand Canyon National Park was established in 1919, funds became available to develop the park and its trails. Phantom Ranch, a Grand Canyon jewel was ready to be built.

| Get Davy Crockett’s new book, Grand Canyon Rim to Rim History. Read more than a century of the history of crossing the Grand Canyon Rim to Rim. 290 pages, 400+ photos. Paperback, hardcover, Kindle, and Audible. |

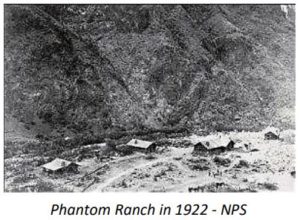

In 1921, The Fred Harvey Company started major construction near Rust/Roosevelt to establish a tourist destination at the bottom of the Grand Canyon. Designs were under the direction of Mary Jane Colter (1869-1958) and the structures were architected by others. Initially, the ranch was referred to as “Roosevelt Chalet.”

In 1921, The Fred Harvey Company started major construction near Rust/Roosevelt to establish a tourist destination at the bottom of the Grand Canyon. Designs were under the direction of Mary Jane Colter (1869-1958) and the structures were architected by others. Initially, the ranch was referred to as “Roosevelt Chalet.”

Early in 1922, progress was reported, “The Fred Harvey Co. have had a force of 15-20 men constructing Roosevelt Chalet near the mouth of Bright Angel Creek. Substantial stone cottages and a central mess hall and social center are well underway. No expense is being spared to make the camp one of the great attractions for Grand Canyon visitors, especially those who wish to make the mule-back trip from rim to rim via the new Kaibab suspension bridge.” The new bridge was being used daily by park rangers and Fred Harvey pack trains. Soon Colter insisted that the ranch be named after the side creek nearby, named Phantom Creek.

Phantom Ranch was initially advertised to be a sort of halfway house for South Rim sightseers who wanted to make a three-day trip to Ribbon Falls and back without camping out or make a seven-day trip to the North Rim and back. Phantom Ranch was initially advertised to be a sort of halfway house for South Rim sightseers who wanted to make a three-day trip to Ribbon Falls and back or make a seven-day trip to the North Rim and back. “For tourists making rim the rim trip, it is a natural stopover and resting place. It is reported visitors are coming in increasing numbers to the North Rim from Utah points. The longer trips can be taken either in hiking or horseback parties. In each instance, there are government guides with each party and these men, besides knowing every inch of the country, are entertaining with their short talks on the points of interest that are encountered.

Phantom Ranch was initially advertised to be a sort of halfway house for South Rim sightseers who wanted to make a three-day trip to Ribbon Falls and back without camping out or make a seven-day trip to the North Rim and back. Phantom Ranch was initially advertised to be a sort of halfway house for South Rim sightseers who wanted to make a three-day trip to Ribbon Falls and back or make a seven-day trip to the North Rim and back. “For tourists making rim the rim trip, it is a natural stopover and resting place. It is reported visitors are coming in increasing numbers to the North Rim from Utah points. The longer trips can be taken either in hiking or horseback parties. In each instance, there are government guides with each party and these men, besides knowing every inch of the country, are entertaining with their short talks on the points of interest that are encountered.

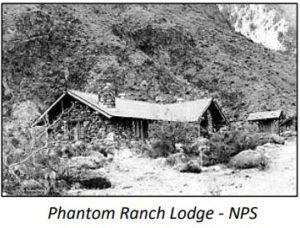

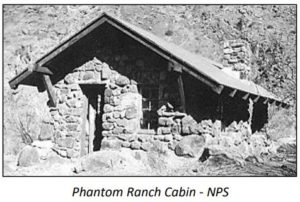

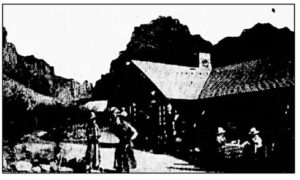

Phantom Ranch opened on June 15, 1922, with four cabins, a lodge with a kitchen, and a dining hall. The ranch was designed to be self-sufficient, with an orchard of peach, plum, and apricot trees. Also included was a chicken shed and yard, a blacksmith shop, a water reservoir, and a barn. Additional cottonwood trees were planted. The cabins had two beds, a fireplace, baths, showers, running water, and eventually telephones connected to El Tovar Hotel on the South Rim and electricity. The first telephone line from Phantom Ranch to the South Rim was completed in 1922 and worked well. Phone stations were also at Pipe Creek and Indian Garden. It was boasted, “It is the deepest down of any canyon ranch in the world. Nothing is like it anywhere else.”

Phantom Ranch opened on June 15, 1922, with four cabins, a lodge with a kitchen, and a dining hall. The ranch was designed to be self-sufficient, with an orchard of peach, plum, and apricot trees. Also included was a chicken shed and yard, a blacksmith shop, a water reservoir, and a barn. Additional cottonwood trees were planted. The cabins had two beds, a fireplace, baths, showers, running water, and eventually telephones connected to El Tovar Hotel on the South Rim and electricity. The first telephone line from Phantom Ranch to the South Rim was completed in 1922 and worked well. Phone stations were also at Pipe Creek and Indian Garden. It was boasted, “It is the deepest down of any canyon ranch in the world. Nothing is like it anywhere else.”

More improvements to Phantom Ranch were wanted, but Ralph Cameron (1863-1953), who built the Bright Angel Trail and had fought for control of the trail and mines for years, became an enemy of the National Park. In 1922, as a U.S. Senator for Arizona, he fought hard and succeeded in denying $90,000 of funds for Park improvements. He said the expenditure of the funds would be “worse than useless to gratify the whims of a few who would profit by the expenditures.” Cameron vowed to fight fund approval for all national parks. “I intend to do all I can to stop such fooled expenditures. It is no wonder that the people wonder why their taxes are large when so much money goes into such sinkholes.” Months later, the Senate authorized $75,000 for the Grand Canyon National Park. He eventually lost reelection.

More improvements to Phantom Ranch were wanted, but Ralph Cameron (1863-1953), who built the Bright Angel Trail and had fought for control of the trail and mines for years, became an enemy of the National Park. In 1922, as a U.S. Senator for Arizona, he fought hard and succeeded in denying $90,000 of funds for Park improvements. He said the expenditure of the funds would be “worse than useless to gratify the whims of a few who would profit by the expenditures.” Cameron vowed to fight fund approval for all national parks. “I intend to do all I can to stop such fooled expenditures. It is no wonder that the people wonder why their taxes are large when so much money goes into such sinkholes.” Months later, the Senate authorized $75,000 for the Grand Canyon National Park. He eventually lost reelection.

Early Phantom Ranch Visitors

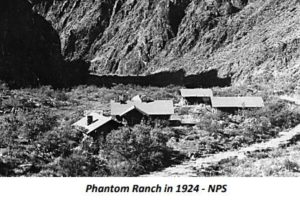

A guest in 1924, Walter I. Pratt (1864-1940), of Iowa, wrote, “At Phantom Ranch, we found three sleeping cabins with four beds each, a larger central building with the kitchen and dining room, a garden that was just getting started, a barn, and a chicken house. Bright Angel Creek is out the backyard and an irrigation ditch at our front door. Green grass is all about and many small trees have just been set out. Small boulders have been piled in rows, making most of the fences. Two years ago, it was just desert.” Rates to stay there were $6 per person, per day.

A guest in 1924, Walter I. Pratt (1864-1940), of Iowa, wrote, “At Phantom Ranch, we found three sleeping cabins with four beds each, a larger central building with the kitchen and dining room, a garden that was just getting started, a barn, and a chicken house. Bright Angel Creek is out the backyard and an irrigation ditch at our front door. Green grass is all about and many small trees have just been set out. Small boulders have been piled in rows, making most of the fences. Two years ago, it was just desert.” Rates to stay there were $6 per person, per day.

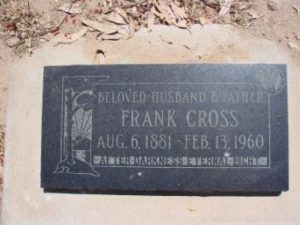

Phantom Ranch was staffed with a married couple as caretakers who worked very hard to make guests feel welcome. Early caretakers 1923-1930 in order were Mr. and Mrs. Harbin of Los Angeles, by Mr. and Mrs. Frank Taft of Kansas City, Missouri, Mr. and Mrs. Noah Kelly of San Francisco, Mr. and Mrs. Baker of Los Angeles, Mr. and Mrs. Nat Greer, Mr. and Mrs. Frank Quirk, Mr. and Mrs. D. H. Barber, Mr. and Mrs. Frank Cross, Mr. and Mrs. Tom L. Moore, of Williams, Arizona, and Mr. and Mrs. Dan Thomas, of Greeley, Colorado.

The Phantom Ranch caretaker in 1924 was an Irishman, Noah Kelly, who had tended bar in Williams, Arizona, for 16 years. His duties were described as “head cook, dishwasher, chambermaid, bottle washer, all in one.” He was very friendly, and knocked on Pratt’s cabin door, letting them know supper was ready. When asked about rattlesnakes, Kelly said that they had only killed sixteen along the trails the previous year. He said, “We have king snakes too, but we make pets of them. They chase the rattlers away and keep the rats and mice out of the cabins. If you have mice in your house, the king snake will crawl down the chimney if it can’t get in any other way. We only had three of them last year.” He downplayed the pack rats. “They aren’t bad. Sure, they steal your combs and stockings, but for anything they take, they always leave you a stone. I have had them steal my money.”

The Phantom Ranch caretaker in 1924 was an Irishman, Noah Kelly, who had tended bar in Williams, Arizona, for 16 years. His duties were described as “head cook, dishwasher, chambermaid, bottle washer, all in one.” He was very friendly, and knocked on Pratt’s cabin door, letting them know supper was ready. When asked about rattlesnakes, Kelly said that they had only killed sixteen along the trails the previous year. He said, “We have king snakes too, but we make pets of them. They chase the rattlers away and keep the rats and mice out of the cabins. If you have mice in your house, the king snake will crawl down the chimney if it can’t get in any other way. We only had three of them last year.” He downplayed the pack rats. “They aren’t bad. Sure, they steal your combs and stockings, but for anything they take, they always leave you a stone. I have had them steal my money.”

A group gathered, listening to this colorful man. There were only two small wooden benches, so the men were seated on the ground with their backs propped up against the flat side of boulders. As dusk approached, bats flew above and occasionally seemed to take a dive at them.

How Phantom Ranch Got its Name

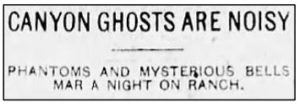

Phantom Ranch was named after Phantom Canyon, which joins Bright Angel Canyon in The Box, about two miles above the ranch area. How did Phantom Canyon get its name? Today, people are told that Phantom Canyon got its name because it seemed to appear and reappear in a phantom-like haze. Others say early explorers would miss the creek because it was so hidden. Still others are told that from the South Rim, it cannot be seen and thus was a phantom. There is no historical evidence for these reasons. They are false sanitized narratives that evolved to not scare away visitors. The true eerie story was told consistently by Phantom Ranch caretakers in the 1920s.

Phantom Ranch was named after Phantom Canyon, which joins Bright Angel Canyon in The Box, about two miles above the ranch area. How did Phantom Canyon get its name? Today, people are told that Phantom Canyon got its name because it seemed to appear and reappear in a phantom-like haze. Others say early explorers would miss the creek because it was so hidden. Still others are told that from the South Rim, it cannot be seen and thus was a phantom. There is no historical evidence for these reasons. They are false sanitized narratives that evolved to not scare away visitors. The true eerie story was told consistently by Phantom Ranch caretakers in the 1920s.

Early Phantom Ranch caretaker, Noah Kelly explained that a prospector, John Shane, who he knew well, was killed there years earlier at the mouth of a side canyon just up the creek. A stone had fallen off the wall “and smashed him flat.” When prospectors and hunters were in the area, they kept seeing a strange light on the wall where Shane had been killed. They thought it was spooky, and the canyon was called Phantom Canyon. Kelly said he had seen this strange light during a storm. “I saw what looked just like someone was carrying a lantern going from place to place. Then it would go out and in a minute would come again. It sure would, and sometimes it was just awful dim like and then it would brighten up and the thunder kept on rolling. I just laid in bed and covered up my head. I sure did.”

Early Phantom Ranch caretaker, Noah Kelly explained that a prospector, John Shane, who he knew well, was killed there years earlier at the mouth of a side canyon just up the creek. A stone had fallen off the wall “and smashed him flat.” When prospectors and hunters were in the area, they kept seeing a strange light on the wall where Shane had been killed. They thought it was spooky, and the canyon was called Phantom Canyon. Kelly said he had seen this strange light during a storm. “I saw what looked just like someone was carrying a lantern going from place to place. Then it would go out and in a minute would come again. It sure would, and sometimes it was just awful dim like and then it would brighten up and the thunder kept on rolling. I just laid in bed and covered up my head. I sure did.”

When Ralph W. Pierson (1901-1968), of Bloomington, Illinois, stayed at Phantom Ranch in 1926, he looked for the phantom. “That evening at Phantom, we talked and played cards, and hoped that the phantom would appear. Many claim that they have seen a whitish shape flitting around in the recesses on the high cliffs, but I didn’t see any sign of the ghost.”

In 1927, a correspondent for the Kansas City Star wrote, “Phantom Ranch is so called for the excellent reason that it has a phantom. I did not see it myself because it appears only to the guilty, but I know it is there because many who have seen it told me about it and described it. Their descriptions do not all agree, but descriptions seldom do, especially for descriptions of phantoms. The phantom appears at night on the face of the mountain. It is white as all phantoms are and has something of the shape of a veiled human figure. I made the discovery that the chalet that had been assigned to me was right at the foot of the cliff on which the phantom appears. With all the mountains around there, it had to be the one over my roof that was thus distinguished.” He spent a sleepless night, hearing spooky noises. The sound turned out to be from some concrete pieces that fell onto a tub on the enclosed porch of his cabin. It is understandable why others in the future did not want people to know the true story of Phantom Ranch’s namesake.

Famed Grand Canyon explorer Harvey Butchart (1907-2002), also said that near the mouth of the creek, on the cliffs, one could see at times a projection of a cloaked phantom figure

Phantom Ranch Becomes Popular

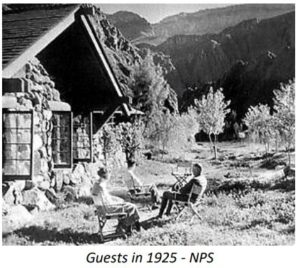

By 1925, four tents were added which could accommodate four people each, and a wooden bathhouse with dressing rooms. Chickens were taken down there for a coop by Lester Guy Carr (1885-1955) of Williams, Arizona.

By 1925, four tents were added which could accommodate four people each, and a wooden bathhouse with dressing rooms. Chickens were taken down there for a coop by Lester Guy Carr (1885-1955) of Williams, Arizona.

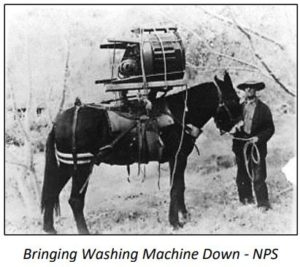

Mrs. Lloyd Day from Louisiana wrote, “One cannot see Grand Canyon from the rim. The trip down is an experience full of thrills and when one realizes that everything to eat at Phantom Ranch, all supplies and accommodations have to be transported by pack mules, there comes a tender feeling in the heart of our friend, the mule.”

Leona (Beck) Powell of Kansas City, Missouri, visited Phantom Ranch in 1925. She wrote, “Never did a place look so inviting as did those little stone cottages nestling in a little green spot surrounded by sheer rock walls, hundreds of feet high. One of the first things I saw down there was a mowing machine, while a little farther was a tiny field with a hay rake. Phantom Ranch is a fully equipped ranch, yet on a very tiny scale. Phantom Ranch has every convenience, with the exception of ice, to take care of the venturesome who make the trip down the lone trail. Some day they expect to have an ice plant in the Canyon, but it is now impossible to transport it down there.”

Leona (Beck) Powell of Kansas City, Missouri, visited Phantom Ranch in 1925. She wrote, “Never did a place look so inviting as did those little stone cottages nestling in a little green spot surrounded by sheer rock walls, hundreds of feet high. One of the first things I saw down there was a mowing machine, while a little farther was a tiny field with a hay rake. Phantom Ranch is a fully equipped ranch, yet on a very tiny scale. Phantom Ranch has every convenience, with the exception of ice, to take care of the venturesome who make the trip down the lone trail. Some day they expect to have an ice plant in the Canyon, but it is now impossible to transport it down there.”

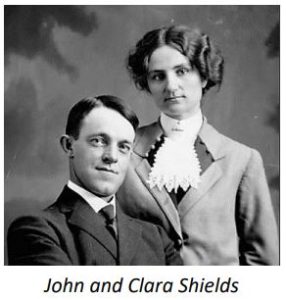

Because of the warmth during the winter, visitors came down into the Canyon year-round. On December 14, 1925, an amazing ad hoc party was held at Phantom Ranch with 20 people. George Meiklejohn Shields (1880-1861), the leader of the Kanab, Utah Band, put on a concert, playing the cornet, the violin, and then sang vocal solos. Others joined in as the sound echoed off the cliffs. Mr. and Mrs. Barber, who manned the geological survey station, sang duets, and other visitors and government men sang, and “everyone had the time of their lives.” Two weeks later, 40 members of the Sierra Hiking Club of San Francisco stayed for several days. Other hiking clubs came down, choosing to make the journey on foot instead of riding on mules. Word was getting around the hiking community that going down by foot into the Canyon was much more enjoyable than on mules.

Because of the warmth during the winter, visitors came down into the Canyon year-round. On December 14, 1925, an amazing ad hoc party was held at Phantom Ranch with 20 people. George Meiklejohn Shields (1880-1861), the leader of the Kanab, Utah Band, put on a concert, playing the cornet, the violin, and then sang vocal solos. Others joined in as the sound echoed off the cliffs. Mr. and Mrs. Barber, who manned the geological survey station, sang duets, and other visitors and government men sang, and “everyone had the time of their lives.” Two weeks later, 40 members of the Sierra Hiking Club of San Francisco stayed for several days. Other hiking clubs came down, choosing to make the journey on foot instead of riding on mules. Word was getting around the hiking community that going down by foot into the Canyon was much more enjoyable than on mules.

The official NPS Guide stated, “It is a sad mistake for persons not in the soundest physical training to attempt on foot. Nearly every day, one or more trampers, overconfident of their endurance, find the way up too arduous and have to be assisted by guides and mules sent down for them from the rim.” They were charged $5 for this service.

An English woman who had traveled the world was overwhelmed by her 1926 visit to Phantom Ranch. “She was of the opinion that the trip which she had just made was the grandest in her life. She had seen the Himalayas, the Andes, the mountains of Austria and Switzerland, but to her, all of their charm and grandeur was dwarfed when the Grand Canyon of the Colorado River was placed side by side.”

An English woman who had traveled the world was overwhelmed by her 1926 visit to Phantom Ranch. “She was of the opinion that the trip which she had just made was the grandest in her life. She had seen the Himalayas, the Andes, the mountains of Austria and Switzerland, but to her, all of their charm and grandeur was dwarfed when the Grand Canyon of the Colorado River was placed side by side.”

Royalty descended into the Canyon in 1926, Prince Gustatavus Adolf (1906-1947) of Sweden, heir to the throne. His group of 18 went all the way to Phantom Ranch on a July day when it was 110 degrees at the bottom. The Prince, age 20, immediately went off alone to swim in Bright Angel Creek. King Alfonso XIII (1886-1941) of Spain also visited and took exclusive possession of the Ranch. Crown Prince Christian Frederik of Denmark visited later with a large party.

In August 1926, a group of 32 scientists, teachers, and students from Princeton University made the trek to Phantom Ranch on foot. Florence A. Brooks (1883-1986) of Fresno, California said, “After being greeted by the genial and hospitable host, and refreshing with good cold water, we were shown to our cottages, equipped with cold showers and a comfortable bed. A splendid dinner revived us, new acquaintances were made, and the marvelous trip of the day was discussed.”

Stolen Melons at Phantom Ranch

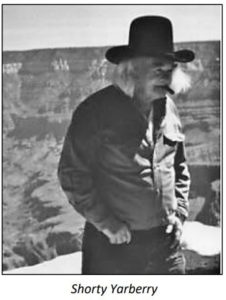

During July 1925, muleskinner and guide, Colonel Custer “Shorty” Yarberry (1877-1957), the hen herder and guide at Phantom Ranch, reported that several men went into a big melon patch at the Ranch and had stolen and destroyed many melons. Two men rode away to head off the men who were traveling up to the North Rim. Also, rangers at Roaring Springs were phoned, asking them to intercept the thieves. The men were caught, a Mr. Whitlock, John Ives, and another man who was their cook, all from Kanab, Utah. “It was reported that Whitlock comes from a good family but was in some sort of trouble about a car which he stole at Kanab and abandoned at the Canyon. He came here alone but met up with the other men here and persuaded them to go back with him to ‘fix things up,’ when they got into this other trouble. They were taken up to the South Rim and turned over to a Justice of the Peace.

Flagstaff Teacher’s College Hiking Club Camp

In 1926, the Flagstaff Teacher’s College Hiking club got permission to establish a permanent camping area up Phantom Creek (a side canyon northwest of Phantom Ranch). In late May 1926, the club, including eight faculty members and fifteen students, went down the South Kaibab trail in the afternoon and arrived at Phantom Ranch by sundown. They were led by Thelma Belle Davis (1900-1973) who had extensive experience in mountaineering. She had explored up Phantom Creek two months earlier with others and fell into the creek getting “a lung full of water.” Still, she returned with this large group.

In 1926, the Flagstaff Teacher’s College Hiking club got permission to establish a permanent camping area up Phantom Creek (a side canyon northwest of Phantom Ranch). In late May 1926, the club, including eight faculty members and fifteen students, went down the South Kaibab trail in the afternoon and arrived at Phantom Ranch by sundown. They were led by Thelma Belle Davis (1900-1973) who had extensive experience in mountaineering. She had explored up Phantom Creek two months earlier with others and fell into the creek getting “a lung full of water.” Still, she returned with this large group.

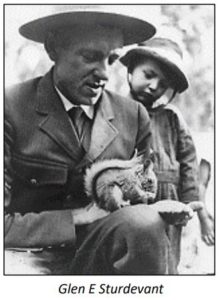

The next morning, they went up Phantom Creek. “The permanent camp will be two miles up Phantom Creek from Bright Angel Creek. It will be headquarters from which trips will be made for geological and other forms of study observation.” The Camp was named, “College Camp.” They were accompanied by Park Naturalist Glen Ernest Sturdevant (1895-1929) and received plenty of support from Park Superintendent John Ross Eakin (1879-1946). In 1929, Sturdevant drown with fellow ranger Fred Johnson (1898-1929) when their boat went through Horn Creek Rapid on the Colorado River, while they were trying to cross the river. They had been conducting an inventory of natural history and archeological sites. He is buried in the Grand Canyon Pioneer Cemetery.

The next morning, they went up Phantom Creek. “The permanent camp will be two miles up Phantom Creek from Bright Angel Creek. It will be headquarters from which trips will be made for geological and other forms of study observation.” The Camp was named, “College Camp.” They were accompanied by Park Naturalist Glen Ernest Sturdevant (1895-1929) and received plenty of support from Park Superintendent John Ross Eakin (1879-1946). In 1929, Sturdevant drown with fellow ranger Fred Johnson (1898-1929) when their boat went through Horn Creek Rapid on the Colorado River, while they were trying to cross the river. They had been conducting an inventory of natural history and archeological sites. He is buried in the Grand Canyon Pioneer Cemetery.

Phantom Ranch Improvements

It was believed that in 1926, 20,000 people descended into the Canyon on its trails. That year, an electricity generator plant was built by Regan Carter (1903-1978). A large force of men came down to lay a pipeline to the powerhouse, dynamiting a ditch. “On Tuesday afternoon at the beginning of the heavy rain which fell, lightning struck the tank, deflecting into the ground nearby but in no way injuring the tank. The men were temporarily stunned, though not one was seriously hurt.”

In 1927, a large recreation building was added, and five more two-bed “Santa Fe” cabins were built along with today’s Canteen dining room. Carpenters and other workmen from McKee Construction Company provided the work. The 1922 dinner bell still hangs east of the dining hall. Raw sewage had been piped into the Colorado River before being replaced with septic tanks and then a sewage treatment plant.

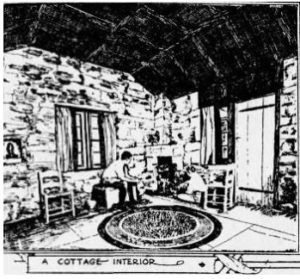

Phantom Ranch in 1927-1928

In 1927, Gertrude Gordon (1900-1959), of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania wrote about her Phantom Ranch caretakers, “Frank Cross (1881-1960) and his wife are in charge, and they know how to make the stranger feel at home. There are trees all around the huts and cabins. The creek flows right behind them. There is a big corral for the animals, a small chicken run, and rabbit hutches. The Crosses are famous for their rabbit pie. They have homemade jellies and preserves and oh, how they can cook.” In the evening, Cross would stop by to get breakfast orders on how to cook their eggs. Early in the morning, he would enter visitors’ cabins, unannounced (no locks were on the doors), and build a warm fire in their fireplaces. “He brings over hot water for you and if the pack rats have carried off the soap in the night, brings more.” Cabins were described as consisting of “one large room with two beds, a fireplace and a shower bath, and a screened and roofed sleeping porch.”

In 1927, Gertrude Gordon (1900-1959), of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania wrote about her Phantom Ranch caretakers, “Frank Cross (1881-1960) and his wife are in charge, and they know how to make the stranger feel at home. There are trees all around the huts and cabins. The creek flows right behind them. There is a big corral for the animals, a small chicken run, and rabbit hutches. The Crosses are famous for their rabbit pie. They have homemade jellies and preserves and oh, how they can cook.” In the evening, Cross would stop by to get breakfast orders on how to cook their eggs. Early in the morning, he would enter visitors’ cabins, unannounced (no locks were on the doors), and build a warm fire in their fireplaces. “He brings over hot water for you and if the pack rats have carried off the soap in the night, brings more.” Cabins were described as consisting of “one large room with two beds, a fireplace and a shower bath, and a screened and roofed sleeping porch.”

Muleskinner and guide, “Shorty” Yarberry, was a character at Phantom Ranch. He was a Texas cowhand who had been at the Canyon since 1919. Just before the mule company was ready to leave the Ranch, Yarberry turned on the phonograph and told unsuspecting Gertrude a mournful tale that he wished he could learn to dance and asked her to teach him. She recalled, “Although not much of a dancer, no one could resist Shorty’s plea, and I encouraged him. ‘You are a good dancer,’ I told him, ‘You are light on your feet. If you keep it up.’ But Shorty still was mournful, ‘Somehow it just seems as if I can’t learn.’” A three-year veteran guide, Jack Way, of Fort Worth, Texas, came by and said, “That Shorty is the best dancer in the country. He just likes getting the girls to teach him to dance.” Gertrude realized she had been spoofed.

Muleskinner and guide, “Shorty” Yarberry, was a character at Phantom Ranch. He was a Texas cowhand who had been at the Canyon since 1919. Just before the mule company was ready to leave the Ranch, Yarberry turned on the phonograph and told unsuspecting Gertrude a mournful tale that he wished he could learn to dance and asked her to teach him. She recalled, “Although not much of a dancer, no one could resist Shorty’s plea, and I encouraged him. ‘You are a good dancer,’ I told him, ‘You are light on your feet. If you keep it up.’ But Shorty still was mournful, ‘Somehow it just seems as if I can’t learn.’” A three-year veteran guide, Jack Way, of Fort Worth, Texas, came by and said, “That Shorty is the best dancer in the country. He just likes getting the girls to teach him to dance.” Gertrude realized she had been spoofed.

Yarberry was the most famous of the early guides employed by the Fred Harvey Company. Guides were combination muleskinners, tourist guides, and entertainers. At Phantom Ranch, they made their headquarters at the mule stables. By 1928, about five employees were kept constantly at the Ranch. “The number of guides varied with the size of the tourist parties. One guide was assigned each ten travelers, and often special guides are secured by smaller groups.” From June through September about 500 people visited the Ranch.

In February 1928, with snow on the South Rim, Worth Osbun Aiken (1873-1960) of Maui, Hawaii, made the trek down to Phantom Ranch while his wife stayed in the warm comforts of El Tovar Hotel. He penned a letter from Phantom Ranch, “It is beautiful down here now in the dusk with the towering cliffs above and a mountain brook singing along in front of my cabin, and the weather at least 20 degrees warmer than up on the rim. If you could see me now, after a hearty, well-cooked beefsteak dinner, in this one room, stone walled, cement floored cabin, with a roaring fire in a cute corner open fireplace.”

In February 1928, with snow on the South Rim, Worth Osbun Aiken (1873-1960) of Maui, Hawaii, made the trek down to Phantom Ranch while his wife stayed in the warm comforts of El Tovar Hotel. He penned a letter from Phantom Ranch, “It is beautiful down here now in the dusk with the towering cliffs above and a mountain brook singing along in front of my cabin, and the weather at least 20 degrees warmer than up on the rim. If you could see me now, after a hearty, well-cooked beefsteak dinner, in this one room, stone walled, cement floored cabin, with a roaring fire in a cute corner open fireplace.”

Non-humans at Phantom Ranch

In 1929, a deer caused quite a stir crossing the Colorado River. The tame deer had free reign of the corridor trail area. One day it was at Phantom Ranch with her two fawns. She jumped in the river, was taken by the current, and went over to the shore at Pipe Creek. Her fawns didn’t follow, but went upriver and crossed the tamer waters near Black Bridge. The fawns went up the South Kaibab Trail to the Tonto Platform. The mother went up Pipe Canyon. Somehow, they met up at Indian Garden.

In 1929, a deer caused quite a stir crossing the Colorado River. The tame deer had free reign of the corridor trail area. One day it was at Phantom Ranch with her two fawns. She jumped in the river, was taken by the current, and went over to the shore at Pipe Creek. Her fawns didn’t follow, but went upriver and crossed the tamer waters near Black Bridge. The fawns went up the South Kaibab Trail to the Tonto Platform. The mother went up Pipe Canyon. Somehow, they met up at Indian Garden.

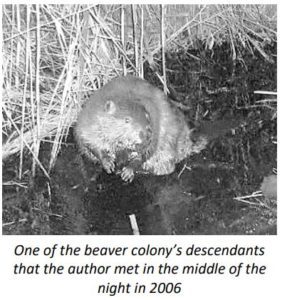

Also, that year a colony of beavers cared for by the Park in upper Bright Angel Canyon migrated down to Phantom Ranch and started to cut down many of the beautiful shade trees that had been planted there. The park rangers were at first patient with the small residents. “Park authorities have felt that the value of the few cottonwoods they destroy in this locality is far less than the value of the beavers themselves and the evidence of their activities as a tourist attraction. There are few places along main traveled trails where the tourist can see nearby old and new beaver cuttings.” They eventually sent the beavers back up the creek, but they kept returning for many years.

Also, that year a colony of beavers cared for by the Park in upper Bright Angel Canyon migrated down to Phantom Ranch and started to cut down many of the beautiful shade trees that had been planted there. The park rangers were at first patient with the small residents. “Park authorities have felt that the value of the few cottonwoods they destroy in this locality is far less than the value of the beavers themselves and the evidence of their activities as a tourist attraction. There are few places along main traveled trails where the tourist can see nearby old and new beaver cuttings.” They eventually sent the beavers back up the creek, but they kept returning for many years.

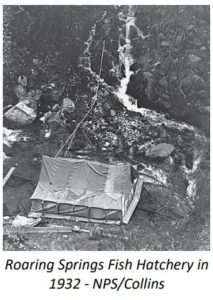

In 1930, 100,000 fish eggs visited Phantom Ranch, brought from Montana. Rangers took the eggs on their backs from the ranch and planted them in side streams (Phantom Creek, Wall Creek, and Ribbon Creek). Fishing trout at Bright Angel Creek soon became a major reason for people to descend into the canyon. The first eggs had been brought down in 1920. In 1932, a fish hatchery was operated at Roaring Springs.

In 1930, 100,000 fish eggs visited Phantom Ranch, brought from Montana. Rangers took the eggs on their backs from the ranch and planted them in side streams (Phantom Creek, Wall Creek, and Ribbon Creek). Fishing trout at Bright Angel Creek soon became a major reason for people to descend into the canyon. The first eggs had been brought down in 1920. In 1932, a fish hatchery was operated at Roaring Springs.

A horse named “Old Bob” pulled a four-horse coach for more than a decade on the South Rim. He pulled kings and presidents. In 1932, as faster automobiles replaced his coach, Old Bob lost his job. Instead of being auctioned off, an official at the transportation company let “Old Bob” retire to Phantom Ranch to graze along Bright Angel Creek. After eight years at Phantom Ranch, he died in 1940.

A horse named “Old Bob” pulled a four-horse coach for more than a decade on the South Rim. He pulled kings and presidents. In 1932, as faster automobiles replaced his coach, Old Bob lost his job. Instead of being auctioned off, an official at the transportation company let “Old Bob” retire to Phantom Ranch to graze along Bright Angel Creek. After eight years at Phantom Ranch, he died in 1940.

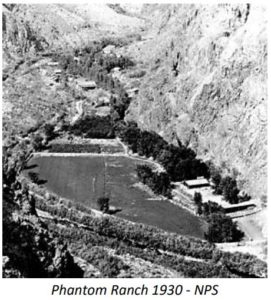

Visitors to Phantom Ranch in the Early 1930s

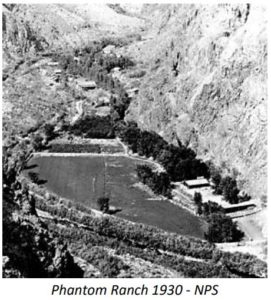

In 1930, Phantom Ranch was visited by about 500-600 people from June to September. The rest of the year had far fewer visitors because the North Rim was closed in early October. “They have accommodations of a central dining room, of a large recreation hall, designed for dancing, card playing, and other amusements.” There was also a diesel-powered electric plant, a small orchard of peach trees, fig trees, and an alfalfa tract. The cottonwood trees that were planted had grown to more than 50 feet high. A central restroom with shower baths was completed along with a sewer system.

In 1930, Phantom Ranch was visited by about 500-600 people from June to September. The rest of the year had far fewer visitors because the North Rim was closed in early October. “They have accommodations of a central dining room, of a large recreation hall, designed for dancing, card playing, and other amusements.” There was also a diesel-powered electric plant, a small orchard of peach trees, fig trees, and an alfalfa tract. The cottonwood trees that were planted had grown to more than 50 feet high. A central restroom with shower baths was completed along with a sewer system.

During peak times, about five employees stayed down at Phantom Ranch to take care of the visitors. One visitor remarked, “I would have slept well had it not been for the croaking of the frogs.”

During peak times, about five employees stayed down at Phantom Ranch to take care of the visitors. One visitor remarked, “I would have slept well had it not been for the croaking of the frogs.”

In 1932, it was observed, “Nearly every day we see long trains of pack mules going down through one rim to the other. The rim-to-rim tourist trips are apparently few. For some people, the trip down the narrow trails is one of keen delight, while for others it is full of terrors which they have no desire to repeat.” For those who ventured up to the North Rim, they found the prices to be outrageous. A pound of butter was 40 cents, and a quart of milk was 19 cents. In 1933, more than 12,000 people used the Kaibab Trail.

Ride on the USGS Tram

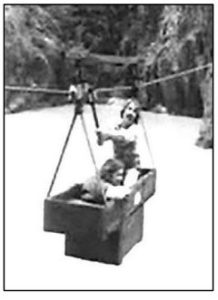

In 1922, a small cable tramway on a cable of 500 feet was constructed upriver from the Swinging Suspension Bridge that the Geological Survey used to monitor the river’s water flow and silt. It can still be seen today.

In 1922, a small cable tramway on a cable of 500 feet was constructed upriver from the Swinging Suspension Bridge that the Geological Survey used to monitor the river’s water flow and silt. It can still be seen today.

Taking a ride on the U.S. Geological Survey tram, upriver from the bridge, was a common activity in the evening for Phantom Ranch visitors. R. M. Clark from Santa Monica, California, came down from the North Rim. He wrote, “Three ladies that came from the South Rim and myself were the only visitors at the Ranch this night. After our evening meal, it being a clear moonlight evening, the guide and a government (USGS) official and we four visitors walked down to the Colorado River. The government official’s duty at this point was to measure the flow of the river twice every 24 hours. This is being done on account of the Boulder Dam project. The river drops as much as 30 feet, and raises 60 feet, this being due to rain and snow melting in the northern states. We crossed the river in a tram attached to a cable. It was 9:00 p.m. when we returned to our camp and we enjoyed the balance of the evening with music appropriate for the occasion.”

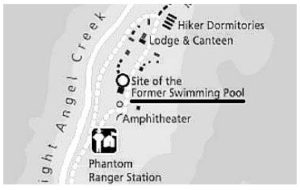

Swimming Pool

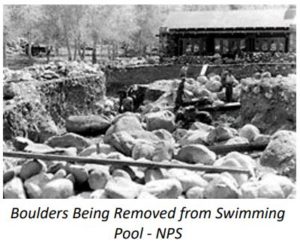

In 1934, the CCC built a swimming pool at Phantom Ranch behind the employee bunkhouse. It was 72 feet by 40 feet and 19 feet deep. They had to remove hundreds of massive boulders that the creek had deposited during floods over thousands of years. The pool walls and floor were concrete and rock.

In 1934, the CCC built a swimming pool at Phantom Ranch behind the employee bunkhouse. It was 72 feet by 40 feet and 19 feet deep. They had to remove hundreds of massive boulders that the creek had deposited during floods over thousands of years. The pool walls and floor were concrete and rock.

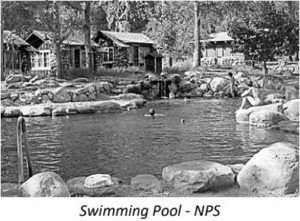

A tourist watched the construction and said, “As if the 5,000 feet of the canyon weren’t deep enough, they’re digging another hole for a swimming pool!” Diverted water came from Bright Angel Creek. It would be the centerpiece of Phantom Ranch for many decades. Deer would drink out of the pool as they journeyed through the area.

A CCC worker said, “The first time I saw Phantom Ranch the swimming pool was just completed. I remember diving into the water and finding little chunks of ice floating there. The temperature down there was about 105 so you can imagine the shock I received.”

A CCC worker said, “The first time I saw Phantom Ranch the swimming pool was just completed. I remember diving into the water and finding little chunks of ice floating there. The temperature down there was about 105 so you can imagine the shock I received.”

The pool was used until about 1969. It was discontinued because it was a maintenance chore, had been overused, and without chlorine, experienced bacteria growth causing health problems. It was filled up in 1970 with many items including hand-carved doors, a piano, oil-burning stoves, grills, the pool table, and items from the old blacksmith shop.

The pool was used until about 1969. It was discontinued because it was a maintenance chore, had been overused, and without chlorine, experienced bacteria growth causing health problems. It was filled up in 1970 with many items including hand-carved doors, a piano, oil-burning stoves, grills, the pool table, and items from the old blacksmith shop.

Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim Series

- 46: Part 1 (1890-1928)

- 47: Part 2 (1928-1964)

- 48: Part 3 (1964-1972)

- 49: Part 4: Aiken Family

- 50: Part 5: The Races

- 135: Part 6: Early Guides

- 136: Part 7: Prof Cureton

- 137: Part 8: Kolb Brothers

- 138: Part 9: Phantom Ranch

- 139: Part 10: More on 1927-1949

Sources:

- Arizona Republic (Phoenix, Arizona), Sep 17, 1922, Dec 28, 1924, Jun 26, 1925, May 6, 27, 1928, Sep 9, 1928, Jun 16, 1941

- Los Angeles Times (California), Jun 28, 1925, Feb 9, 1929

- The Coconino Sun (Flagstaff, Arizona), Feb 17, Aug 11, 1922, Dec 5, 19, 1924, Jan 9, 16, Feb 27, Jun 5, 22, Jul 24-25, 1925, Dec 18, 1925, Jan 1, Mar 26, Jun 4, 13, 1926, Sep 16, Oct 7, 1927

- Williams News (Arizona), Feb 17, 1922, Jun 26, 1925, Jun 26, 1925, Dec 2, 1927, Jul 13, 1928

- The Salt Lake Tribune (Utah), Feb 24, 1922, Aug 15, 1922, Nov 21, 1923, Sep 16, 1928

- Arizona Daily Star (Tucson, Arizona), Feb 22, 1925, May 8, 1928, Jun 16, 1929

- The Richfield Reaper (Utah), Sep 25, 1913, Jun 13, 1929

- Tucson Citizen (Arizona), Nov 27, 1927, Apr 5, Jul 8, 1928

- The Topeka State Journal (Kansas), Jul 15, 1922

- The Lincon Star (Nebraska), Aug 13, 1922

- Calgary Herald (Canada), Aug 26, 1922

- Iowa City Press-Citizen (Iowa), May 14, 19, 1924

- The San Francisco Examiner, Feb 8, 1925

- Bogalusa Enterprise and American (Louisiana), Jul 9, 1925

- The Pantagraph (Bloomington, Illinois), Feb 27, 1926

- The Ponca City News (Oklahoma), May 30, 1926

- The Winslow Mail (Arizona), Jun 11, 1926

- The Pittsburgh Press (Pennsylvania), Jan 9, 1927

- The Kansas City Star (Missouri), Jul 2, 1922, Jan 23, 1927

- Stockton Evening and Sunday Record (California), Feb 26, 1927

- Redwood City Tribune (California), Apr 18, 1927

- Honolulu Star-Bulletin (Hawaii), Feb 20, 1928

- The San Bernardino County (California), Sun, Mar 4, 1928

- Omaha World-Herald (Nebraska), May 6, 1928

- Brooklyn Times Union (New York), May 9, 1928