Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 31:25 — 38.2MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

Many of today’s ultrarunners think that ultrarunning was invented during their lifetime. An article appeared in April 2020 Ultrarunning Magazine that stated falsely, “the format that most of us know as ‘ultrarunning’ today (trail and road races, typically 50k to 100 miles) is barely 50 years old.” Such statements are ignorant of the rich history of the past and the ultrarunners who paved the way, running ultradistances on dirt roads and trails for more than two centuries.

Many of today’s ultrarunners think that ultrarunning was invented during their lifetime. An article appeared in April 2020 Ultrarunning Magazine that stated falsely, “the format that most of us know as ‘ultrarunning’ today (trail and road races, typically 50k to 100 miles) is barely 50 years old.” Such statements are ignorant of the rich history of the past and the ultrarunners who paved the way, running ultradistances on dirt roads and trails for more than two centuries.

In April 2020, Runners World published an article proclaiming falsely that the first 100-mile ultra was held in 1974. This is part 4 of a rich 100-miler history. More than 1,000 ultrarunners finished 100 miles in less than 24 hours before 1974. If you missed the other parts, you can start with Part 1.

| Subscribe to the Ultrarunning History Podcast. Visit https://ultrarunninghistory.com/subscribe-to-podcast/ |

Ultarunning and the 100-miler face extinction

During the late 1800s, and the early 1900’s for about 30 years, 100-milers and Pedestrian six-day races were held indoors, when they were a unique spectator and gambling sport until about 1908. In 1889 the home of Pedestrianism, the original Hippodrome, Madison Square Garden was demolished. It had become a “patched-up, grimy, drafty, combustible old shell.” A new Madison Square Garden arena was constructed on the site and opened its doors to the golden era of multi-day bicycle races.

In the early 1900’s, as local laws in America were more widely passed outlawing multi-day running and bike races, indoor 100-milers ceased and the 100-miler faced the threat of extinction again. In the former heart of 19th century ultrarunning, New York City, it was written, “These protracted tests of physical endurance serve no good purpose. They prove nothing beyond the fact that some men can force themselves to harmful exertion even when every fiber of their physical being is in active revolt.”

But a flicker of life still remained in America. Starting in 1905 the 100-miler reemerged into the outdoors on the dirt roads in Illinois, thanks to some legendary marathon runners from Chicago who sought to attain the 100-mile distance.

The 1906 mountain trail 100-miler

In the early 1900s, American railroad contractors, who were building a mining railroad to the Tarahumara village of Bocoyna, were spellbound with the running exploits of the people who lived in the canyons. The workers amused themselves by wagering large sums of money on long-distance running races.

A historic 1906 race was held from Bocoyna to Minaca and back, about 110 miles on “exceedingly rough” trails over the mountains. William Demming Hornaday (1868-1942), an American journalist, and the publicity director for the National Railways of Mexico, was there to watch this race and reported that the Americans collected a purse of $100 for the winner.

“Great interest was manifested in the race, for the sum offered was quite a fortune to the members of the tribe. A council of war was immediately held by the chiefs, and two of the fastest runners were selected to do battle for the prize. The pair were also subjected to a close inspection by the Americans, who wagered large sums on the result.”

Consider that the 1906 Bocoyna-Minaca mountain trail 100-mile race predated Western States 100 by more than 70 years!

Albert Corey

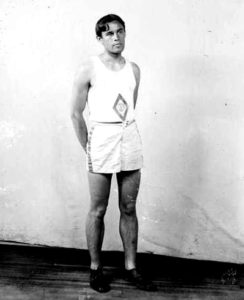

Corey immigrated to America in 1902, went to work in the stock yards, and read that athletes were training at Marshall field for the 1904 Olympic Games to be held in St. Louis, Missouri. He showed up one day in his running clothes, and after a quick running audition, was invited to become a member of the Chicago Athletic Association. It was observed that he took short strides, ran with a mid-foot strike, with a running form that was smooth.

Even though Corey was not an American citizen, he competed at the 1904 Olympics in St Louis, Missouri, representing the United States. He ran the Olympic Marathon which was on a tough course, 24.85 miles long and placed second with 3:34:16. He also won a silver medal in the four-mile relay race.

After the Olympics, Corey set his sights on breaking the 100-mile world record which was erroneously thought to be established by himself of 16:22, while serving in the French Army. (The world’s best 100-mile time was 13:26:30 held by Charles Rowell of England. But perhaps Corey held the amateur record.) At the age of 26 he said he had already run more than 30,000 miles.

It was reported, “He weighs 139 pounds, five feet five, and has neither gained nor lost a pound in the last eight years. A hard day’s workout, which means a run of from eight to fifteen miles, never fazes him in the least and he seldom loses more than a half-pound in weight. He is said to be one of the best proportioned and most ideally built athletes that ever ran on Marshall Field.”

Milwaukee to Wisconsin: about 100 miles

At Waukegan Illinois, about mile 50, he was greeted by a large crowd who came out to watch him run through town. He stopped for twenty minutes, was given a rubdown and ate a light meal. His speed became slower and slower, and he eventually realized it would be impossible to break the record. He backed off his pace and just concentrated on finishing his long grind. A Fort Sheridan, the soldiers came out to give him a warm reception. Corporal Sidler tried to pace him for a while but gave up after a couple miles.

He finished in front of the Chicago Athletic club with a large crowd waiting for his arrival. His 100-mile time was a disappointing 23:15. He was wrapped in a blanket and hurried to a waiting carriage and was driven to his home.

Corey said, “It was simply impossible to make any fast time over the roads. At some places it was impossible to run, and it was hard work to walk. I had a terrible time in the swamps north of Kenosha and wandered about for several hours trying to find my way. I was at last picked up by William Hale Thompson in his auto and found I was several miles out of my way. The heavy going tired me greatly and several times I was forced to stop to rest. Several miles out I was paced by youngsters who came all the way to town with me. I think I shall make another attempt at breaking the record as I am confident that I can do the distance in sixteen hours or less.”

The first AAU sanctioned 100-mile race

Corey still claimed to hold the 100-mile world record. The week before the race both of them did a multi-day trial run to find the best roads for the race to be held on. They accomplished about 25 miles per day.

The race was a bust. Five miles out, the automobile’s tire exploded, and the car had to be abandoned. The two runners did their best to plod along through ankle deep mud. Both dropped out after only 28 miles at the 4:20 mark, in Racine, Wisconsin. “The athletes floundered in mud on the main roads and were glad, doubtless, that the accident put an end to the long grind.”

1907 Milwaukee to Chicago

Corey again made arrangements to go for the record, but on October 18, 1907, his attempt was postponed because of poor road conditions. “An automobile party reported the roads in such a condition that it would be foolhardy to attempt the long grind afoot.”

After a week postponement, Corey made new plans. He would be paced for the first ten miles by another ultrarunner, Sidney Hatch. The plan was to run for 55 minutes during each hour and rest for five minutes.

On October 24, 1907, Corey started at Milwaukee at 9:00 p.m. in front of the Milwaukee Athletic Club. Corey and Hatch were guided by four automobiles with headlights and a brilliant moon with perfect weather. Soon after starting Corey was affected by stomach troubles which greatly slowed him during the night. He stopped frequently and was rubbed down by his trainer, Charles Wilson. He ran sometimes five miles at a stretch without slowing to a walk, and other times would go only two or three miles between rests. At one point both runners and automobiles lost their way, but soon got back on course.

“Corey ate little on the way. For breakfast he had two eggs and a little milk. He felt for a time during the night as though he never wanted to eat again.”

Along the way they came suddenly upon a stream where there was no bridge. Time was lost while his crew used some boards to construct a way for Corey to run across. His pace increased significantly and by late morning he was back an hour ahead of schedule. With a few miles to go, he ran strongly and was seen chatting with his crew as they drove along. “With the cheers of his companions and a large crowd of spectators ringing in his ears, Corey made a final sprint as he neared the First Regiment armory.”

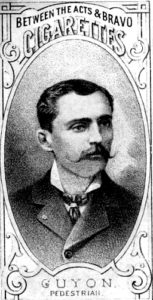

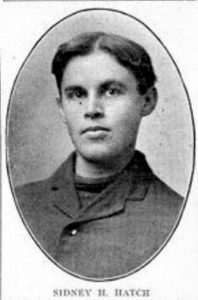

Sidney Hatch

In 1906 Hatch helped organize The West Chicago Harriers promoting cross country runs and trail races. Hatch developed his endurance as a newspaper circulation man, delivering papers on the run.

In 1906 Hatch broke into the news and received attention from the sport when he won the “All Western” marathon (24.85 miles) with 2:47:24 on dirt roads in St. Louis, Missouri. He ran with fellow Chicagoan, Alexander Thibeau who finished in second. Hatch, Corey, and Thibeau dominated the marathons that emerged in the Midwest during that time, evolving into a 1908-1910 “marathon mania.”

In 1908, Hatch ran in the Olympic marathon in London and finished fourteenth.

1909 100-mile race at Riverview Park, Chicago

A compromise was found to run the race on a turf course at the amusement park. Hatch had been successful a few months early on the same track when he won the “All Nations” Chicago Marathon held at Riverview Park.

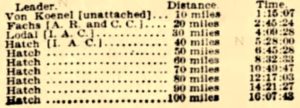

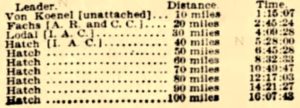

For the 100-mile race, some elite runners were in the field. The starters included Sidney Hatch, Charles Lobert, Olaf Lodal, Edward Van Koenel, Erwin Theise, Hugo Fach, and Frank Mensing, all from the Chicago area. Lobert was the favorite. His claim that he was the best, was the catalyst for organizing the race. He boasted that he would break the 100-mile western record that was thought to be held by Corey, of 16:33. Leading up to the race, the entrants trained together taking long jaunts out in the country.

Frank Mensing only finished 19 miles and quit after turning his ankle. Von Koenel, who had led the race early on, dropped at mile 28. His feet were worn raw by his shoes. Theise stopped at mile 44 with stomach issues. After he took a rest and a short nap he decided he was done.

By mile 67, Hatch had a commanding eight-mile lead and pushed that to a ten mile lead at mile 84 when he took a three-minute break to rub out some hip pain. It was observed, “Hatch seemed to be running more within himself than any of the others.” During the entire race he was off his feet for only a total of 18 minutes. Olaf Lodal ran well until mile 71, when his left leg was seized up with cramps, causing him to quit.

Hatch won in 16:07:43, running the final mile in a blistering 5:19. “He made a good spurt at the finish and brought the crowd which had been been watching the race to its feet in a storm of applause.” When he finished, Lobert was nine miles behind. While Hatch’s 100-mile time was not a world record it was a world amateur best. Only three finished, Hatch, Lobert (17:33), and Hugh Fachs (18:00).

Hatch went on to dominate and win many marathons over the next few years.

1916 Milwaukee to Chicago

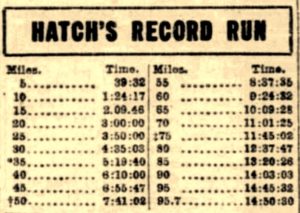

“Preparing for the run he took a twenty-hour snooze and a breakfast of soft-boiled eggs and tea. After a ten-mile walk, he went back to bed and slept until 6 p.m. A cup of tea and several slices of toast were all he ate just before the start.”

“Hatch wore long gray trousers, a jersey and mittens. Four automobiles convoyed the runner and for the first few miles out, a score of schoolboy athletes ran along with him. 2,000 persons gather to see Hatch and his partner off.”

“With a strong, cutting wind in his face, Hatch bent to his task and ran twenty-five miles more before he pulled up at Highland Park to drink hot lemonade and to have his legs rubbed.” High school students turned out in Kenilworth to cheer him. “Hatch then ran all the way to the Rush street bridge, piloted by motorcycle and mounted police, who stopped all traffic. When he reached the river, the bridge was raised and Hatch lost fully two minutes.” At that point Hatch requested that the finish be at his Mystic Athletic clubhouse instead of at Grant Park. Work spread fast and a large crowd greeted him at the finish.

He stopped only three times (total time 20:30) for rubdowns and refused all food except orange juice and hot lemonade. His only stop during the night was at Waukegan, Illinois at 4 a.m. when he received a rubdown. He ran the first 69 miles in 11 hours. Hatch’s crew car, a six-passenger “Jeffery” did not break down and proved that it could run at low gear on rough country roads. The company would use that in its advertisements.

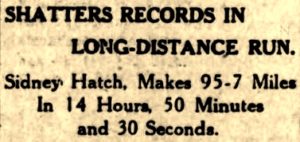

Hatch finished the run on a “dog trot,” and shattered the record, finishing in 14:45:32. After a brisk rubdown, he requests a bowl of ice cream. “After a short rest, he said he did not feel as weak as he had expected. He lost eleven pounds on the long run and his face was drawn and his eyes sunken. His legs were sore, and he had blisters on the bottoms of his feet.” He went to bed for a 24-hour sleep.

Hatch announces his retirement

Hatch did not retire as announced. In February 1917 he finished 4th with 2:47 at the Pennant Marathon from the Bronx to New Rochelle, New York and back.

1917 100-mile race for Red Cross

The 100-mile race was scheduled to be held May 25, 1917, but a week before the race, he notified the AAU that he had fallen and injured himself during a training run. Actually he had broken a rib during a friendly boxing match and couldn’t run for several weeks. It was decided to postpone the race until June 16th. The rescheduled race was promoted as a benefit for the Red Cross and was to be held in New York City. In early June it was written, “Hatch, who runs about as gracefully as a Jersey cow being chased by a milkmaid is grinding out from 15 to 20 miles a day in preparation for the race.”

The Great War halts 100-milers

Where did they go?

What happened to the great ultrarunners from Chicago?

During an October 1918 battle near Brieulles, France, as Hatch was taking a message, shells began to fall. He dodged into a hole and was buried by a blast. After being helped out, with his leg wounded by shrapnel, he continued to take the message to headquarters. “It was a thousand yards down ‘the death path’ and the ground was popping with shells. It was a real death patch, but Hatch swung down it with the same ease he might start a championship marathon race.” He made it and ran back with a message response.

Hatch was decorated for “extraordinary heroism” and was awarded the Purple Heart and Distinguished Service Cross. He returned home to Illinois as a hero in May 1919.

Sidney Herbert Hatch died on October 17, 1966, exactly 50 years to the day after he made his famous 100-mile run on October 17-18, 1916. He was 83 years old. There was no mention of his running accomplishments in his obituary.

A modern-day Milwaukee-Chicago 100-mile Turkey Trot is held yearly to raise money for ALS research.

“Besides having scores of victories to his credit as a runner, he has attracted considerable attention as a wrestler, skater, boxer, and walker. He is the possessor of a large collection of trophies including solid gold medals, some of them diamond studded.”

Albert Corey finished 4th in the 1908 St. Louis marathon. Club members, Hatch and Thibeau finished ahead of him. That year France sought to have Albert Corey represent his homeland in the Olympic Games. He passed on that, wanting to run again for America. But it was too late to add him. “Corey was indignant at being left off the team and charges the failure to name him to ‘spite-work.’ He has practically given up the hope of taking part in the marathon at London and is now only sorry that he didn’t take up the offer of French authorities.”

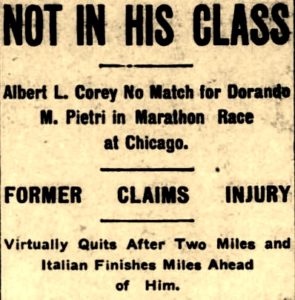

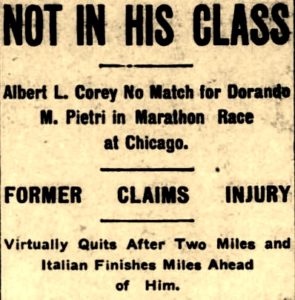

In January 1909 Corey ran a match marathon in Chicago against Italian great, Dorando Pietri who had finished the 1908 London Olympic Marathon in first place, but later was disqualified because of help received when he kept collapsing with a few yards to go. The match race was a bust when Corey started limping after only two miles because of a sore ankle. “Corey gave a miserable account of himself, whether by accident or just because he knew he was up against a better man.” Pietri won alone in 2:55. Doctors could find nothing wrong with Corey’s ankle. He was branded a coward by the press and his running career was over. He died at the age of 48 in 1926.

As World War I concluded, attention would eventually return to the 100-miler.

The parts of this 100-mile series:

- 54: Part 1 (1737-1875) Edward Payson Weston

- 55: Part 2 (1874-1878) Women Pedestrians

- 56: Part 3 (1879-1899) 100 Miles Craze

- 57: Part 4 (1900-1919) 100-Mile Records Fall

- 58: Part 5 (1902-1926) London to Brighton and Back

- 59: Part 6 (1927-1934) Arthur Newton

- 60: Part 7 (1930-1950) 100-Milers During the War

- 61: Part 8 (1950-1960) Wally Hayward and Ron Hopcroft

- 62: Part 9 (1961-1968) First Death Valley 100s

- 63: Part 10 (1968-1968) 1969 Walton-on-Thames 100

- 64: Part 11 (1970-1971) Women run 100-milers

- 65: Part 12 (1971-1973) Ron Bentley and Ted Corbitt

- 66: Part 13 (1974-1975) Gordy Ainsleigh

- 67: Part 14 (1975-1976) Cavin Woodward and Tom Osler

- 68: Part 15 (1975-1976) Andy West

- 69: Part 16 (1976-1977) Max Telford and Alan Jones

- 70: Part 17 (1973-1978) Badwater Roots

- 71: Part 18 (1977) Western States 100

- 72: Part 19 (1977) Don Ritchie World Record

- 73: Part 20 (1978-1979) The Unisphere 100

- 74: Part 21 (1978) Ed Dodd and Don Choi

- 75: Part 22 (1978) Fort Mead 100

- 76: Part 23 (1983) The 24-Hour Two-Man Relay

- 77: Part 24 (1978-1979) Alan Price – Ultrawalker

- 79: Part 25 (1978-1984) Early Hawaii 100-milers

- 81: Part 26 (1978) The 1978 Western States 100

- 87: Part 27 (1979) The Old Dominion 100

Sources:

- Buffalo Morning Express (New York), Jul 11, 1878

- The Inter Ocean (Chicago, Illinois), Aug 21, 1904, Dec 8, 1905, Sep 3, 1906, Oct 23, 25 1907, Apr 29, Jun 12, 1908, Oct 4, 1908, Jul 25, 1909

- The Daily Review (Decatur, Illinois), Aug 31, 1904

- The Perry Daily Chief (Iowa), Aug 17, 1905

- The Pittsburgh Press (Pennsylvania), Aug 17, 1905

- The Minneapolis Journal (Minnesota), Dec 8, 1905

- The Oshkosh Northwestern (Wisconsin), Dec 8, 1905

- Chicago Tribune (Illinois), May 6, Aug 21, 1906, Jan 3, Jul 20, 25 1909, Oct 16, 19, Nov 5, 1916, May 18, 1917, Oct 22, 1918

- The Oklahoma Post (Oklahoma), Aug 25, 1906

- The Journal Times (Racine, Wisconsin), Sep 1, 4, 1906, Oct 18, 1907, Dec 8, 1917

- The Minneapolis Journal (Minnesota), Sep 4, 1906

- The Buffalo Commercial (New York), Nov 1, 1906

- The San Francisco Examiner (California), Oct 25, 1907

- Muncie Evening Press (Indian), May 27, 1909

- Lincoln Journal Star (Nebraska), Jul 23, 1909

- Nanaimo Daily News (British Columbia, Canada), Jul 19, 1909

- Fort Wayne Daily News (Indiana), Jul 24, 1909

- The La Crosse Tribune (Wisconsin), Jul 24, 1909

- The Leavenworth Times (Kansas), Jul 24, 1909

- Times Union (Brooklyn, New York), Jul 26, 1909

- Rutland Daily Herald (Vermont), Aug 18, 1911

- Louis Star and Times (Missouri), Oct 9, 1916

- The Indianapolis News (Indiana), Oct 17-18, 1916, Jan 6, 1919

- The Brooklyn Citizen (New York), Oct 18, 1916

- The Salt Lake Herald-Republican (Salt Lake City, Utah), Oct 18, 1916

- The Pantagraph (Bloomington, Illinois), Oct 19, 1916

- The Winnipeg Tribune, Nov 22, 1916

- The Star Press (Muncie, Indiana), Nov 5, 1916

- The Allentown Leader (Pennsylvania), Dec 15, 1916

- Buffalo Evening News (New York), Dec 16, 1916

- The Dispatch (Moline, Illinois), Feb 23, 1917

- The Times (Munster, Indiana), Mar 24, 1917

- The Ithaca Journal (New York), Apr 19, 1917

- Joseph Gazette (Missouri), Jun 6, 1917

- The Daily Review (Decatur, Illinois), Jun 1, 1917

- Louis Post-Dispatch (Missouri), Jun 2, 1917

- The Rock Island Argus (Illinois), May 28, 1919

- The Province (Vancouver, Canada), Sep 18, 1927