Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 32:29 — 41.9MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

For at least 150 years, running or walking 100 miles within 24 hours has been an impressive feat sought after by thousands.

For at least 150 years, running or walking 100 miles within 24 hours has been an impressive feat sought after by thousands.

Part 4 of this 100-miler series covered the history of 100-mile races held in America in the early 1900s before World War I. But during this period, there were 100-mile races held in other places around the world, especially in England. During the early 1900s a remarkable shift occurred. In the late 1800s, America was the home for ultra-distance walking competitions. But as pedestrian competitions fell out of favor and outlawed in the U.S., ultrawalking ceased for a time. The shift went back to the old country and 100-mile amateur walking competitions eventually became very popular in England.

| On ultrarunninghistory.com, each article/episode takes about 30 hours of effort to research, write, script, edit, publish and publicize. Each month more there are more than 100,000 downloads of these history stories.

Help is needed to continue this effort. Please consider becoming a patreon member of ultrarunning history. You can become part of the effort to preserve and document this history by signing up to contribute a few dollars each month. Visit https://ultrarunninghistory.com/member |

London to Brighton

More than 100 years ago, there are a few venues and courses that had a significant impact on the history of ultrarunning, 100-mile races, and endurance sports in general. These include Madison Square Garden in New York City, Agricultural Hall in London, and above them all, the London to Brighton route (52+ miles) in England.

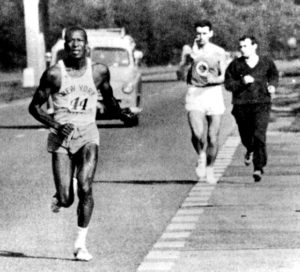

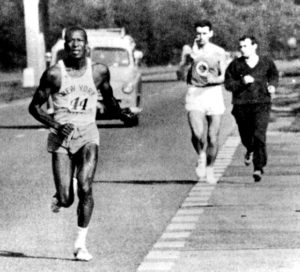

For many decades, whether on foot, on bike, on horse, or in an automobile, the road to Brighton was the place to race, including 100 miles on foot. Eventually many ultrarunning legends would complete on the Brighton Road including Don Ritchie, Cavin Woodward, Ted Corbitt, Eleanor Robinson, Sandra Kiddy, Donna Hudson, Alastair Wood, Bruce Fordyce. Park Barner, Stu Mittleman, Jim King, Ruth Anderson, and Frank Bozanich. London to Brighton was traditionally a one-way race of 52-55 miles, but in the first half of 20th century, it was also used to compete 100 miles by walking or running a double London to Brighton.

Brighton Road

In the mid-1800s, the seafront affluent resort city of Brighton became very popular as the railroad was built from London about 52 miles away. Prior to that, people came by horse coaches that made the trip multiple times per day with ever-increasing speed.

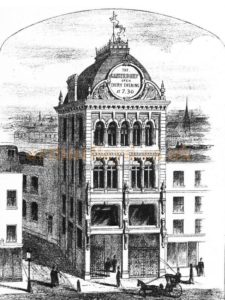

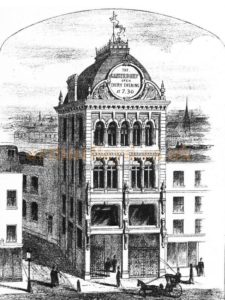

Brighton was a city of the upper class and featured an Aquarium which opened in 1872. It included marine exhibits, a 100,000-gallon tank, sea lions, an octopus, and a distinctive clock tower and gateway. It was also the site for organ recitals, concerts, lectures, and exhibitions. Day trips to Brighton became popular and railroad speed records were boasted about for the route.

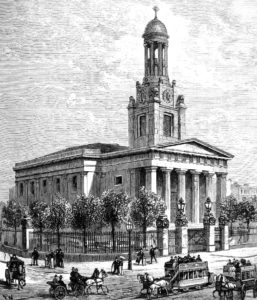

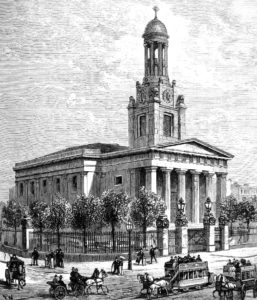

The road to Brighton was measured from the Big Ben clock tower north of Westminister Bridge in London to the Aquarium in Brighton. The clock tower was completed in 1859 and at the time was the largest and most accurate four-facing striking and chiming clock in the world. The tower stands 315 feet and is found on the north end of the Palace of Westminster. London to Brighton ran across River Thames on Westminster Bridge which was originally completed in 1750, and replaced in 1862, the oldest bridge still crossing the Thames.

The original course went through the towns of Croydon, Redhill, Horley, Crawley, and Cuckfield. Over the years the route competed increased in distance somewhat with the creation of modern roads and more towns to go through.

Early Cycling London to Brighton

Participants in the new sport of cycling started to ride along the route. This would soon prompt runners and walkers to also give it a try.

As early as 1869. John Mayall Jr. was the first person to reach Brighton from London by velocipede. He accomplished it in 12 hours, in time for dinner and then he attended the second half of a concert in the Grand Hall. Soon afterwards, C. A. Booth pressed harder to better the fastest known time to 9:30.

In 1870 T. Moon, “an expert bicyclist” set the first fastest known road cycling time on the route of 5:40. A few days later he accomplished a double Brighton Road, 104 miles in 15 hours. He stopped for breakfast, a lengthy lunch, and breaks for tea along the way. A couple years later, the Amateur Bicycle Club promoted a cycling race, which was won in 5 hours, 25 minutes.

Early London to Brighton on Foot

Racing on foot from London to Brighton started early, even before cycling races. The first known running race was conducted on January 30th, 1837, when two professional runners, John Townsend and Jack Berry competed. Townsend, 45, known as the “The Veteran” won in 8:37. Berry quit with four miles to go.

Years passed but more attention was given to pedestrian feats on the road when Benjamin Trench of Oxford University accomplished a sub-24-hour 100+-miler in 1868 by accomplishing a double. He walked from Kennington St. Mark’s Church to Brighton and back in 23 hours for a heavy wager.

In 1869, W. M. Chinnery and H. J. Chinnery, two well-known amateur runners, members of the London Athletic Club, walked London to Brighton in 11:25. It was written, “This feat is almost unparalleled in the recorded feats of modern amateur pedestrianism.”

By 1876, wagers began to influence accomplishments by foot on the famed road. Sir John Lynton was offered 1,000 guineas on a challenge to wheel a barrow from London to Brighton in 15 hours. He carried out the bumpy trip easily, wheeled a bamboo barrow with handles six feet long, and dressed in a “running costume.”

In 1878, P. J. Burt claimed the official fastest known time on foot with 10:52, using a starting point at the clock tower on the north side of Westminster Bridge (Big Ben) in London to the Aquarium in Brighton which turned into the standard start and stop point.

More matches took place. In 1885, C. L. O’Malley, an accomplished athlete, walked against a competitor and lowered the record by more than an hour. A barefoot competition was conducted on the Brighton road in 1882. The furthest competitor with bloodied feet, almost made it, but fainted in pain with four miles to go.

By 1897 large foot races were held from London to Brighton organized by the Polytechnic Harriers. That year there were 37 starters. The winner, Edward “Teddy” Knott, (later the founder of the Surrey Walking Club) finished in 8:56:44. At that time, he was credited as the first to cover the distance on foot in less than nine hours. “Go as you please” walking or running races began on the course in 1899 with 14 starters at Big Ben. The winning time was 6:58:18. In 1902, cyclists showed off, and demonstrated that they could ride the course to Brighton and back, 104 miles, in a shorter time than runners could do one trip. They succeeded in 5:50.

Horses and Automobiles

1902 London to Brighton and Back – 104 miles

The Surrey Walking club stepped into 100-miler history on October 31, 1902 when they held the first “London to Brighton and Back” walking competition, with a distance of about 104 miles. Instead of using the traditional starting point at Big Ben, the race started and ended at the club headquarters, about ten miles to the south, in South Croydon. With the different starting point, the route still covered the entire London to Brighton Course twice for 104 miles.

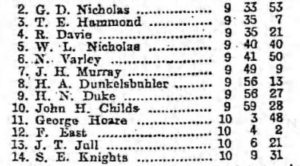

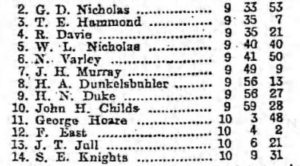

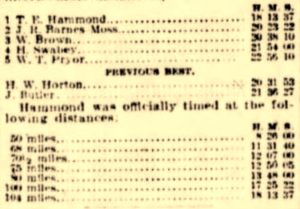

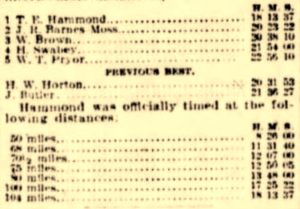

A crowd of several thousand people turned out to see the historic start. It was reported, “One of the most important affairs in road walking contests was the London to Brighton and back race of the Surrey Walking Club. Ten hardy ‘walkists’ turned out. The start took place at South Croydon, from whence the walkers had to pass by Westminster clock tower, thence to Brighton Aquarium and back the same route.” Jack Butler won, with an impressive time of 21:36:27. Two others finished in less than 24 hours, G. H. Schofield and W. J. Taylor.

Thus, a new 100-mile standard was set and more walkers in England wanted to demonstrate their abilities reaching 100 miles going from London to Brighton and back. A couple weeks after the initial race, L. Novelli, a hotel owner at Brighton wanted to prove that he could accomplish it in less than 24 hours. “Accompanied by an automobile and a couple of friends, the walkist started off at a brisk pace. Nothing of note happened until the pedestrian ran into a dense fog and the chauffeur had to go on in front and climb the finger posts to find out the way. This state of affairs continued for three miles, when on trying to jump out of the way of a passing auto, Novelli slipped on the roadside and fell.” He sprained his ankle but tried to walk it off. The fog grew worse, forcing him to stop for a while. He eventually made it to Brighton, four minutes over, in 24:04. The story about his attempt was published as far away as Canada and the United States.

1903 Stock Exchange London to Brighton

A historic race took place in May 1903 that truly brought “London to Brighton” into the public spotlight. Early in 1903, William Bramson, a member of the London Stock Exchange decided to try his own walk from London to Brighton. He accomplished it in 12:30. This sparked the idea of organizing a company-wide walk.

One reporter wrote, “Their refreshments, I am told, will consist chiefly of beef-tea and the like, stimulants only being employed to restore suspended animation. I am also given to understand that all the starters were to be sent off in one batch, presumably with their attendants mounted on bicycles in following at the distance of one yard.”

The race was held on May 1, 1903, (May Day, a bank holiday) with eighty-seven starters, who began from Big Ben at 6:34 a.m. Most of them were young stockbroker’s clerks.

“Half of London seemed to be abroad on foot or awheel to be present at the start. At a very low estimate there must have been 30,000 people in the immediate neighbourhood of Westminster, the bridge itself being covered with them as closely packed as they could stand. The 87 competitors went first, headed and surrounded by very necessary mounted police, who had a hard struggle to protect them from the admiring throng. The nine official cars followed in a long string, then the unattached motorists and last of all a confused mob of bicycles and pedestrians struggling forward in the rear.”

Every crossroad was alive with people all along the route. It seemed like a public festival was being held. Flags were put up across the road. “The remaining seven miles to the winning post became more and more of a popular ovation. Horsemen, motors, and innumerable cyclists poured out of Brighton in a continual stream to meet the on-comers.”

This event truly started a walking craze on the road to Brighton and was a historic milestone event for the future of ultrarunning.

1903 London to Brighton and Back

In the morning, a large crowd was gathered at the turnaround point at the Brighton Aquarium. Harry W. Horton, a member of the Herne Hill Harriers, arrived first followed 15 minutes later by Wakefield. The leaders time for the 100 km distance was 12:08. Horton, seeing how far he was in the lead, pushed on hard, reaching 76 miles in 14:50, and 94 miles in 18:23, well ahead of Butler’s course record. With just a mile to go, Horton was struggling, but a glass of champagne revived him. He finished the 104 miles in 20:31:53. A total of five walkers beat 24 hours.

Cyclist vs. Walker

Thomas Hammond

The 1907 Double Brighton 100-miler

Hammond was the obvious favorite going into the race. Despite not being invited, a member of the Manchester Athletic Club, A. R. Edwards, ran the race “bandit” with his own staff of timers and “two automobiles full of edibles of all descriptions, including beef, chicken, eggs and jellies and liquor from champagne down to aerated waters and there was a spirit lamp too, to boil the kettle if it was wanted.” The other runners only had a solitary cyclist carrying refreshments for support.

The start was again at the “Swan and Sugar Loaf” at South Croydon. In the evening, at 9:04 p.m., after the word “Go” was yelled, Edwards jumped into the lead going at a great pace. “The course for nearly three miles was by tram lines, and the cars, automobiles and spectators who ran in front made the going difficult for the walkers.” Edwards was pressed hard by Bill Brown. After a mile Edward’s crew pleaded with him to back off, that the race was for 100 miles, not one mile. But he ignored them and kept “pegging away.” Brown and Edwards traded the lead for the first few miles.

“Nearing Westminster Bridge, the traffic was much congested, and when Big Ben came in sight, Brown’s lead had reduced considerably. The clock tower marked 10.5 miles of the journey.” Brown reached there at 1:35:24, Edwards at 1:23:55, and T. E. Hammond at 1:38:07. “As they reached the Canterbury Music Hall, Edwards dashed ahead and quickly took a big lead, and seemed to draw away from his opponents as every stride.”

At the 21-mile point Hammond finally took the lead and never looked back. Edwards did not worry and said, “He’ll have his bad time shortly. He’s a long way from home.” “Lamps were lighted as a few spots of rain came down. The moon was covered with a mist, and it looked as if the walkers were in for a drenching, but in a short time the weather cleared.” Others caught up to Edwards. After pushing forward in great pain he finally quit after being on the road for eight hours.

“The roads, although rough in places, were on the whole good, and a stiffish breeze tempered the rays of sun.” Hammond held to lead at 50 miles, reaching that point in 8:26. “Hammond put in some fine walking at this point, and although a strong wind blew against him his time was truly remarkable. Keeping up the pace, he swung around the official timekeeper at Brighton Aquarium (100 km) in 10:30:36.” He had a 90 minute lead on the others.

“Hammond started on the homeward tack. The going was frightful on account of the dust kicked up by automobiles and cyclists. At every mile Hammond increased his lead and with victory in sight he again reeled off more than five and a half miles to the hour. Hammond passed the winning post wonderfully fresh and well. He got a great ovation from the crowd present.”

“The secrets of Hammond’s success are his perfectly natural style of walking. A pace of six miles an hour is to him apparently an ordinarily easy rate of progression. Standing 5 ft. 11 inches high and of comparatively slender build, Hammond gets a long stride without seeming to do in owing to his rapid leg movement. His age is still well on the right side of thirty, so further honours in the record-breaking way doubtless await him.”

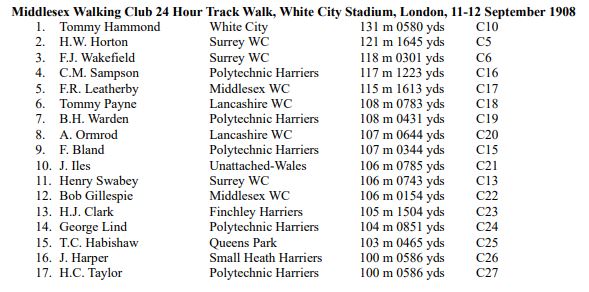

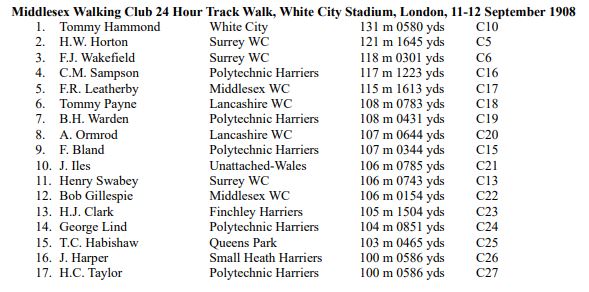

1908 Middlesex Walking Club 24-hour race

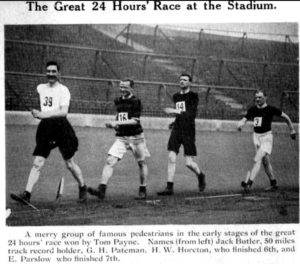

Bill Brown took the early lead walking the first mile in 8:26. “Hammond exercised great self-control in the matter of keeping down his pace in the early stages of the journey.” Jack Butler, also an elite walker who had held records also contended for the lead.

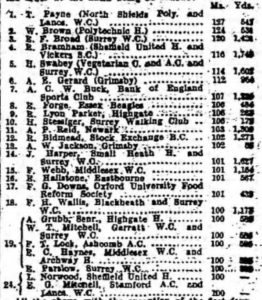

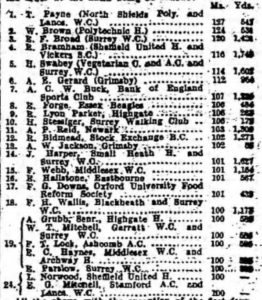

Finally at around the 50 km (31 miles) mark, Hammond took the lead with a time of 5:11:47. From that point he increased his lead over his opponents. He reached 50 miles in 8:36:31 with a mile lead and passed 100 miles at 18:08:50. He continued on with his strong swinging gait and won with an astonishing 131 miles which was a world’s walking best and he smashed other walking records along the way. (The professional record, running allowed, was held by Charles Rowell of England, with 150 miles set in 1882 at Madison Square Garden.)

“Those who knew best the record-breakers capabilities had predicted a remarkable performance and were not disappointed, as, although Hammond had more than one bad time, his superb courage and dogged determination enabled him to absolutely smash the then existing records.”

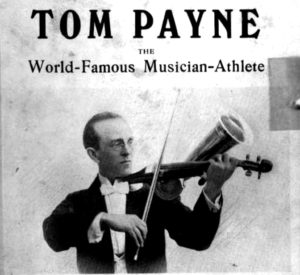

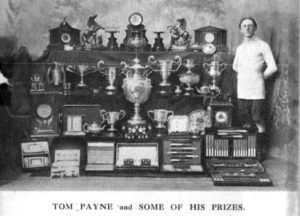

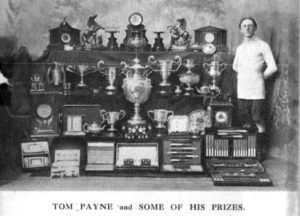

Tom Payne

Payne was a small man, 5 feet, 4 inches and only 112 pounds. He said, “Nature did not bless me with either undue length of body or length of limb, nor strength out of the ordinary, yet by hard, continuous training, I was able to overcome and defeat opponents who were much better gifted than me as regards build and strength.”

Payne competed in more races and in 1907 started to win, beating established champions such as Jack Butler. Payne competed in the 1908 24-hour race in London and finished sixth with 108 miles, reaching 100 miles for the first time.

1909 Blackheath Harriers’ 24 Hours race

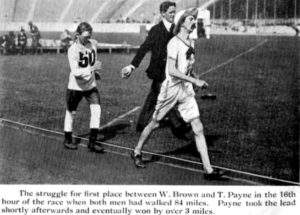

On September 17, 1909 another highly competitive 24-hour race was held at White City Stadium in London, England, open to all clubs. The entrant field was huge, with fifty walkers who started at 5 p.m. in perfect weather. Payne competed along with the previous year’s champion and world record holder, Thomas Hammond. Current and previous London to Brighton winners were also in the field. The early leaders included Jack Butler, Bill Brown, and A. R. Edwards.

During the third hour, H. V. L. Ross, the current London to Brighton champion and record holder put on a furious pace of more than seven mph and rapidly caught the leaders. “But he soon paid the penalty, for shortly before completing 25 miles he had to give up.” Butler and Hammond also dropped out early before 40 miles. “It was a curious coincidence that all of these competitors complained of cramp in the stomach.” The leader, J. Iles, reached 51 miles is record time but “had shot his bolt” and after the next lap retired for more than an hour. He twice tried to get going again but it didn’t work and he quit.

Payne reached 100 miles in 18:08:55. He eventually won the race with 127 miles. An impressive 25 walkers reached 100 miles in less than 24 hours, the most in history up to that time in a single race.

The 1911 Centurion Club

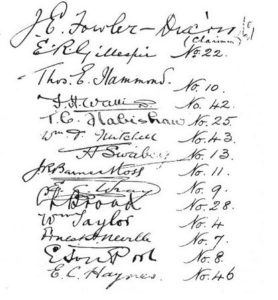

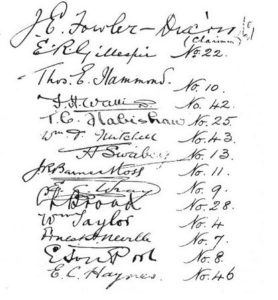

James Edwin Fowler-Dixon who was present at the organization meeting was elected president, honored for his 100-mile walk in 1877. He was given the Centurion number of 1. Each Centurion received a number in order of the completion of the qualifying walk entered into the minute book. They tried to go back in history a few years and award those who were believed to have achieved the milestone in the 1900s. Many were missed who succeeded in the late 1800s and professionals were not eligible.

London to Brighton and Back legend, Tommy Hammond was appointed the first secretary/treasurer of the organization and was club captain for the next 36 years.

1912 London to Brighton and Back

The first race to qualify new members of the “Centurion Club” was the 1912 London to Brighton and back race held in September. A. C. St. Norman of South Africa entered. He had competed in the Olympic 10 km walking race (disqualified) and the Olympic marathon at the 1912 Olympic Games. There were only five walkers who started the 1912 Brighton double race. Three of them successfully qualified for the Centurions. “St. Norman showed fine judgement and he is evidently suited by a long journey on the road. After allowing the leaders to force the pace, he came up at the 38th mile to lead.” At the 100 km turn-around in Brighton, with 12:17:12, he had a 23-minute lead. He went on to win by more than an hour over the others with a time of 21:18:45 and was the first new member of the Centurions since it had been established.

1914 London to Brighton and Back

The classic 100+ miler, the double Brighton was again held in 1914. The Surrey Walking Club finally decided to open up the race to non-members. “The Surrey Walking Club can certainly claim to be doing its best to further distance walking in as unselfish a manner as possible. For the first time in the sport’s history, every walker an opportunity of testing his ability at the double journey without the necessity of previously becoming enrolled as a member.” The 1914 race was won by E. F. Broad in 19:57:57 with the second best time ever and won the “Hammond-Neville Trophy.” This was the same man who one the first Stock Exchange London to Brighton walk in 1903. A veteran’s division was held for those 45 and older. George Hesketh of Manchester Walking Club, age 48 won with 23:41:28.

1921, 1926, and 1929 London to Brighton and Back

W. Baker was an engineer who worked nights and had very recently taken up walking. He had an accident while cycling, and after recovering from a broken leg decided to instead take up walking. He joined the Queens Park Harriers Club.

For the 1929 edition, twenty-five walkers started. Baker went out fast and had the early lead at Big Ben (10 miles). He held onto that lead and won again with a time of 18:38:07, the third fastest time ever. He was “somewhat distressed” at the finish but recovered. Fourteen others reach 100 miles in under 24 hours and qualified as Centurions.

In 1951, the London to Brighton running race was established by the Road Runners Club (RRC). By 1953 the race got the attention of leading long distances runners from other areas of the world including America. Ultrarunning would largely be reestablished in America after World War II because long-distance runners, including Ted Corbitt wanted to run London to Brighton. The London to Brighton race, including its 100-mile version has a hallowed place in ultrarunning history. It was discontinued in 2005 because of increased road traffic and difficulties finding enough volunteers.

The parts of this 100-mile series:

- 54: Part 1 (1737-1875) Edward Payson Weston

- 55: Part 2 (1874-1878) Women Pedestrians

- 56: Part 3 (1879-1899) 100 Miles Craze

- 57: Part 4 (1900-1919) 100-Mile Records Fall

- 58: Part 5 (1902-1926) London to Brighton and Back

- 59: Part 6 (1927-1934) Arthur Newton

- 60: Part 7 (1930-1950) 100-Milers During the War

- 61: Part 8 (1950-1960) Wally Hayward and Ron Hopcroft

- 62: Part 9 (1961-1968) First Death Valley 100s

- 63: Part 10 (1968-1968) 1969 Walton-on-Thames 100

- 64: Part 11 (1970-1971) Women run 100-milers

- 65: Part 12 (1971-1973) Ron Bentley and Ted Corbitt

- 66: Part 13 (1974-1975) Gordy Ainsleigh

- 67: Part 14 (1975-1976) Cavin Woodward and Tom Osler

- 68: Part 15 (1975-1976) Andy West

- 69: Part 16 (1976-1977) Max Telford and Alan Jones

- 70: Part 17 (1973-1978) Badwater Roots

- 71: Part 18 (1977) Western States 100

- 72: Part 19 (1977) Don Ritchie World Record

- 73: Part 20 (1978-1979) The Unisphere 100

- 74: Part 21 (1978) Ed Dodd and Don Choi

- 75: Part 22 (1978) Fort Mead 100

- 76: Part 23 (1983) The 24-Hour Two-Man Relay

- 77: Part 24 (1978-1979) Alan Price – Ultrawalker

- 79: Part 25 (1978-1984) Early Hawaii 100-milers

- 81: Part 26 (1978) The 1978 Western States 100

- 87: Part 27 (1979) The Old Dominion 100

Sources:

- 150th Anniversary of the First London to Brighton Bike Ride

- The London to Brighton Bike Ride

- History of the London to Brighton

- Sandra Brown, Unbroken Contact: One Hundred Years of Walking with Surrey Walking Club

- Belfast News-Letter (Northern, Ireland), Mar 16-1869

- Charles G. Harper, The Brighton Road: The Classic Highway to the South

- The Pittsburgh Press (Pennsylvania), Nov 23, 1902

- The Times (London, England), Nov 1, 1902, Sep 14, 1908

- The Gazette (Montreal, Canada), Dec 1, 1902

- The Fall River Daily Herald (Massachusetts), Dec 1, 1902

- The Guardian (London, England), May 2, 1903, Jun 5, 1903, Jun 24, 1907, Sep 14, 1908, Jun 21, 1926, Jun 22, 24, 1929

- The Sun (New York City), July 21, 1907

- The Observer (London, England), Jun 23, 1907, Sep 19, 1909, Sep 1, 1912, Jun 23, 1929

- 1908 Thomas Hammond, the Record Walker

- Surrey Walking Club Gazette (No, 3, Vol I, 1908)

- E. (Tommy) Hammond, “World’s Best”

- The Gazette (Montreal, Canada), Sep 6, 1909, Jul 5, 1912, Jul 16, 1921

- The Centurions Walking Club

- Centurions History

- List of British Centurions 1911

- Surrey Walking Club Handbook

- Stock Exchange Athletic Club History

- The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, Jun 29, 1907

- Tom Payne – Walker and Musician Extraordinaire

- Tom Payne: The World-Famous Musician-Athlete

- 79th Walk London to Brighton Centenary Race

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Aug 3, 1914

- The Province (Vancouver, Canada), Sep 15, 1929