Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 30:27 — 37.8MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

Ultrarunning, at other distances, also came to life again in South Africa when the Comrades Marathon (55 miles) was held again in 1946 and the Pieter Korkie 50 km was established in Germiston. In England, the London to Brighton running race (52 miles) was established in 1951, using the famed road used by walking and biking events for decades earlier. Ultrarunning was reawakening.

During the prewar decades, hundreds of successful 100-mile attempts and events were held. Would the 100-miler truly come back in the modern era of ultrarunning?

World War II formally concluded, but conflicts continued across the world. During the aftermath of the war, with evolving superpowers, the changing world map, and the resulting Cold War, it made it a difficult time for ultrarunning to emerge widely. But the running sport has always been resilient.

Korean War 100-mile Marches

They were divided up into groups of 50 and those in the last group, the weakest would get shot when they fell out. “Everybody tried to help his buddies, half carrying the weaker ones along.” At the finish of their 100-miler they were taken further by train and stopping near a tunnel. Most of Eggen’s group of 30 were massacred there and he was shot in the leg and again played dead. Six survived, went into the woods and later were found and rescued by American airborne troops.

Great Escape 100-miler

Cotton Picker 100

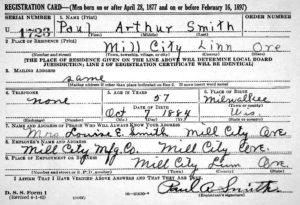

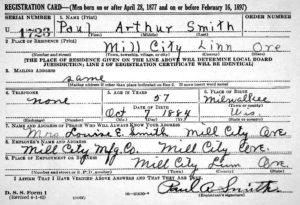

Paul Smith – Oregon’s Walking Man

Walking for so long at about 4,000 feet altitude dried up Smith’s mouth. He tried to spit but instead, out came his false teeth. He said, “I was lucky again. Just as I spit ‘em out I made a grab and caught ‘em before they hit the pavement.”

Paul Smith died in 1962 at the age of 77 of a stroke and was called “Walking Smith” in his obituary.

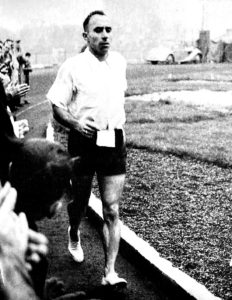

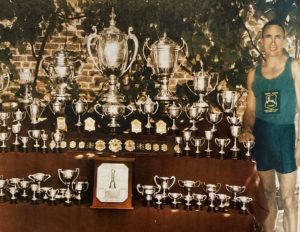

Wally Hayward

Hayward described the chaos. “When I got to the spot that I was to peg, where was an argument going on between a man who pegged some valuable claims and two big bullies who pulled his pegs out and put their own in. There was a big dispute which resulted in the poor man who pegged first being beaten up and his leg broken.”

Formal Running Begins

Hayward was clearly a rookie at the 1930 Comrades and went out fast. By the halfway point he surprised everyone and held a 29-minute lead. Clapham warned him that if he didn’t ease up he would hit the wall and that he did, going up Polly Shorts. But he generally held it together enough to win by 31 seconds with a time of 7:27:26. He would go on to win Comrades a total of five times.

In 1931 Hayward broke a bone in his foot while training for Comrades and the next year was told by a doctor that some chest pain he was feeling, was due to a strained heart. At age 23, he was told to never run again. He put running aside for a few years until a specialist told him the diagnosis was “rubbish” and told him to go home and put on his running shoes. By 1938 he was competing again.

Hayward would run many miles alone on the trails. He wrote, “Sometimes I would run anything from two to six hours cross-country just for the pleasure it gave me, jumping over bushes, running through forests and swamp lands, traversing rivers, anything for fun. By the time I reached home, I am sure many people used to say to themselves, ‘There’s a scruffy and dirty looking guy. I wonder if he ever has a bath or washes his clothes.’”

With the outbreak of World War II, Hayward was attached to the South African Engineer Corp working in railroad construction, building and fixing bridges. As he became stationed in Egypt, he was known to run at least five miles before breakfast. He also ran in Italy and Syria.

Post-war Runnng

Next, he went to England to compete on the world stage. He got four-months’ leave from his job and mortgaged his home to raise money for expenses. He first went and ran the London to Brighton running race, formally in its third year. He boarded with Arthur Newton who passed on wonderful advice. The British running community was very curious how he would do knowing that he was unbeaten in ultra-distances.

100-mile World Record

It finally was time for Hayward to attempt to run 100 miles. Hayward planned to try to break Hardy Ballington’s record time of 13:21:19. (See episode 60). Derek Reynolds of England and 20-year-old Jackie Mekler of South Africa also participated in this “time trial.” Newton gave advice to the rookie 100-mile runners about “hitting the wall” at about mile 70. Running legend, Peter Gavuzzi was Haywards crew chief that day.

Gavuzzi suggested that the runners receive enemas before going to bed the evening before in order to save time spent in the bushes during the race. They went to bed early for the early morning start.

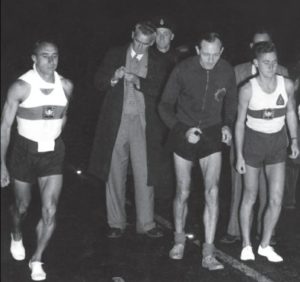

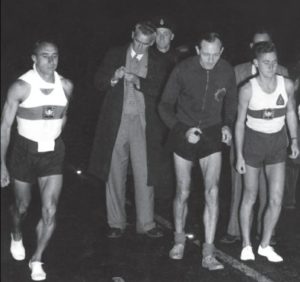

Mekler wrote, “This was exciting stuff for the local inhabitants, many of whom stayed on in the bar at the hotel until the start of the race. A lively party was still going strong when we arrived for a light breakfast at 2:30 a.m. It was absolutely bizarre eating this early morning meal amidst the blaring music being thumped out of a piano. The party came to an abrupt end when we were called to the start. Apart from a pool of light from the hotel, it was pitch dark.” They were off and running at 3 a.m.

24 hours World Record

With the 100-mile world record achieved, Arthur Newton encouraged Hayward to go after the 24-hour world record. Hayward wrote, “I was somewhat dumbfounded, bearing in mind 72 miles was my longest ever training run. 100 miles was bad enough, now he wanted me to tackle a world record that stood at over 152 miles. The man was nuts.”

The attempt was arranged at very short notice for judges, time-keepers, lap scorers and others. The venue selected was at Motspur Park in Surrey. The Motspur Park athletics stadium was built by the University of London in 1928 and achieved fame when the world mile record was set there in 1938. In 1952 Derek Reynolds ran a world record 50 miles on this track in 5:30:22, so it was a fast cinder 440 yard track surface.

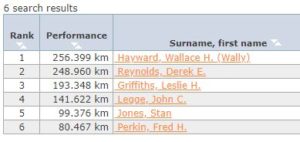

Hayward was still suffering some leg pain from the 100-miler but was reasonably confident that he could compete well. Six runners competed, with his main competition coming from Derek Reynolds of the Blackheath Harriers, winner of London to Brighton in 1952 and the 50-mile world record holder.

Newton and Gavuzzi again assisted Hayward with pre-race preparation and race strategy. “They based Hayward’s schedule on the theory that one had to put in a lot of miles early on to make up for the final hours, when the pace was sure to drop.” They believe he could reach 170 miles.

The historic race began on November 20, 1953 at 11 a.m. in foggy weather. Hayward started out running comfortable seven-minute miles. He reached 50 miles in 6:06:34 with a 12-minute lead. “By 60 miles I was ahead of the existing world record for the intermediate distances and broke the 100-mile world record with a time of 12:46:34, the first to break 13 hours.”

After reaching 100 miles, he came off the track for his only long stop for a massage and a bowl of rice pudding. After a half-hour rest, cramping set in and he could hardly walk. Olympic marathoner, Tom Richards was there and observed, “I think wally made a big mistake when he came off the track. I remember him being laid out on the massage table in the changing rooms. He had stiffened up so much that it was as if rigor mortis had set in. We took it in turns trying to massage some life back into his legs. His huge calf muscles were solid, like oak.”

Eventually he managed to jog on in a painful, awkward-looking style. At dawn he was moving with about ten-minute-miles with four more hours to go. Reynolds was catching up and this helped motivate Hayward to push on.

Newton, age 70, and Gavuzzi kept him well-supplied with tea, soup, and custard. “all the hot drinks were prepared on a little stove. In the early hours I threw a major tantrum because my drinks were not hot, only to be told they had just come off the stove.”

Hayward wasn’t terribly pleased with this performance. He said the veins in the right calf of his leg gave him severe pains during the last ten hours. At the finish he said, “Thank God that’s over. Never again, it was awful.” It was reported, “He flopped exhausted on a dressing room bench and scarcely seemed interested as aides told him he had smashed every known record from eight hours up. During the monotonous jogging around the oval track he lost seven pounds.” He ate two pounds of sugar, drank a pint of tomato soup, and a pint of milk in which were six beaten eggs.

Later he reflected, “I really made a hash of it. Coming off that track at 100 miles was the biggest mistake I ever made. I just couldn’t get going again. For me, it was a wasted opportunity. I should have gone considerably further than I did. If anyone breaks my record, good luck to them.”

About the general experience he said, “This type of race eventually gets very boring. Like a pig with its snout to the ground, you circulate, lap after lap after lap.” At the airport to fly back to South Africa, Hayward said, “After the run I said I was finished, but fools always try these things again.” After a few months, he was ready to compete again. His trip to England cost 550 pounds, worth $20,500 in 2020.

1954 100-mile attempt

On July 17, 1954, at the age of 46, Hayward made another attempt to break the 100-mile world record, this time on a road in South Africa from Standerton to Germiston in mid-winter. The weather turned bad with a strong wind a few hours before the start. Hayward ate a pre-race meal of a huge steak, two eggs, and 12 slices of brown bread and jam. He was away running at 1 a.m. and said, “It was so bitter cold that I put my tracksuit top on, which was not much use as first the rain began, followed by sleet. On top of this I was running into a 40 mph headwind. The judges suggested I abort the run and try in better conditions but I refused. I was determined to carry on, come what may.”

A local reporter wrote, “He missed the word record for the simple reason that he had mistimed, not his run, but the season. He should have tried in summer. At one time the temperature was below zero.”

Wally Hayward passed away at the age of 97 in 2006.

Padre Island, Texas 110-miler

In 1951, Cash Asher (1891-1981), a journalist and author, was the publicity man for the Padre Island Park Board. He came up with the idea of holding a 110-mile walking race the length of the island end-to-end. This would be a way to get more publicity for the island and thus attract tourists

Asher named the race “Padre Island Walkathon.” Word of the race was publicized, and registration opened in early 1953. The format for the event was as a three-day staged race from the southern tip of the island to the northern end. The contestants would walk on no roads, just beach and sandy tracks pounded down by vehicles. This likely was the first post-war trail ultramarathon event in America.

The event started on March 27, 1953. The race filled up with 70 daring starters. None of them had any true experience with this kind of event. The oldest walker was 67 years old and the youngest starter was fifteen. An unusual contestant was Tiny Thompson, a 417-pound taxicab driver from Brownsville, Texas. He was confident and said, “If my ‘dogs’ hold out, I’ll finish right up front.”

The race was started at 8:30 a.m. Sunburn was avoided by most of the walkers who wore long sleeves, long pants, sun “helmets” or caps, “and smeared protective oils on their hands and faces.” More than half the field, 40 of 70, didn’t make it to the Day 1 camp. Day 2 took a heavy toll as 20 walkers didn’t make it all the way to camp and dropped out. Only six contestants started Day 3 for the final 43-mile segment. Three finished. In first place was Jess Shamblin, age 42, of McAllen, Texas, with a total walking time of 28:48 for the 110 miles.

The Padre Island Walkathon created quite a stir in Texas, opening minds to what truly was possible. Covering ultra-distances could be accomplished by non-professionals. The race continued to be held in various forms until 1969. See episode 1 for more details.

March of Dimes 100-miler

Counting side-stops, foot races, and exhibitions, he thought he actually covered 200 miles. A one point he reached an intersection and vowed he would not move another step until $100 was collected. Mitchell’s idea eventually caught on for group walks. The first March of Dimes Walkathon was held in 1958, in Tennessee.

Punishment 100-miler

Man vs. Horse

100-mile Walk for Peace

The Dutch 100-miler

The Four Day march continues to present-day, and has been held for more than 100 years. In 2017, nearly 49,000 hikers participated.

Ron Hopcroft – 100 mile world record

Hopcroft, like the ultrarunners before him, wanted to go after to world-best 100-mile time on Bath Road from Box to London. He knew that Wally Hayward set the record in 1953 of 12:20:28. On October 25, 1958, Hopcroft, of Ealing and a member of Thames Valley Harriers, decided to run from London to Box and set off from Hyde Park Corner at 5 a.m.

Hopcroft wrote, “I had always regarded 5 a.m. as the most unearthly hour and swore that, once I left the army, nothing would ever get me up at this time, but there I was at Hyde Park Corner, all ready to run 100 miles to the little village of Box. A foggy morning, but not too cold, and at 5 a.m. precisely we were way. We being three, John Legge, Bill Wortley and myself.”

At mile five, Hopcroft parted company with the other runners and went on ahead for the rest of the journey alone, battling the clock. He reached the marathon mark in 3:02. Near Maidenhead he was chased by a dog for a couple hundred yards with no one in sight to help.

He reached 30 miles at Reading in under three and a half hours before the hills started. Crowds cheered him on and he reached 50 miles in 5:46:37. “Between 60 and 70 miles I had my first feed, a cup of tomato soup and a very thin savoury sandwich of whole-meal bread dipped in soup. I gobbled it down as quickly as possible while half trotting. At 80 miles (9:36:26) I was really in trouble. For the first time I had two or three little walks, 20 yards or so. Another wash, with my attendants pulling the bucket away from me just as I was enjoying it. Another meal as before and I was away to a really good spell of eight miles at a speed just inside seven-minute miles.”

At mile 95 he was told by a young local cyclist that he was going up his last hill. He had exactly 48 minutes left to beat the record. He said, “By now we had a terrific following of motorists, motor and pedal cyclists and pedestrians running.” Large groups of spectators cheered as they were told that a world record was being broken.

“Only three miles left now. But what is this? Another hill and this proved to be the last straw. I just couldn’t run up it. Pleadings and exhortations almost turned to threats in an effort to keep me running.” His crew chief drove to the finish and then ran toward him bringing their last bottle of pop which he quickly drank. He also received the welcome news that after then next group of trees that it was all downhill.

Hopcroft continued to compete at ultra distances until 1961 after being stopped by an ankle injury and the pressure of business and family commitments. But he served many years as president of running clubs and died at the age of 98 in 2016.

1959 100-mile race in Surrey, England

On October 24, 1959 at 4 a.m., twelve men set out to run twenty times around a five-mile circuit at Walton-on-Thames, Surrey. Race Director Ernest Neville said, “The ambition of a lot of athletes is to say they have run 100 miles, and this is their chance to do it.”

“Good progress was made in the calm conditions and at 30 miles. there were five runners bunched together in the lead. They were all running steadily and keeping within scheduled time, two minutes ahead of Hopcroft’s record pace.”

Arthur Mail, age 37, of Derby, won in 13:17:39 and Don Turner finished second with 13:33:54. The four others did not finish including Hopcroft. Mail said, “I must be crazy to run 100 miles.”

100-mile Love Race

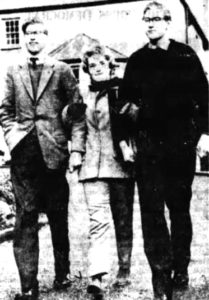

She met the two at a university dance. “From then on, she’d date first one and then the other and sometimes couldn’t be sure which one had showed up to take her out. When the dating blossomed into love, well, things got more confusing by the moment.

Jean said, “I love them both. We have thought carefully about who my future husband might be but we think this is the best way. The winner can take me to the school ball on Saturday, then we’ll get the engagement ring.”

She met the two at a university dance. “From then on, she’d date first one and then the other and sometimes couldn’t be sure which one had showed up to take her out. When the dating blossomed into love, well, things got more confusing by the moment.”

The race began on February 19, 1960. After waving a scarf at the town clock and murmuring, “May the best man win”, Jean jumped into an automobile and followed for a short distance. But she returned to Bangor, expecting to greet the winner when they returned some time the next day.

The twins were allowed to walk or run. After they reached Colwyn Bay, at about the 20-mile mark, Vaughan Clarke was grabbed by students packed into a waiting car who kidnapped him. Howard then quit the race and said, “This has wrecked all our plans.” It was believed that Vaughan was taken to the Liverpool Campus by students who opposed the gamble for a lady. Jean was in a quandary and said, “All this does is increase the suspense and frustrate us all. I do hope Vaughan will be returned so he can continue the race. I do hope Vaughan’s safe. I love them both.”

It was reported that Local Welsh folk hinted the whole thing might have been a hoax and connected to “Rag Week” when students perform stunts to raise money for charity. Vaughn was released and an abbreviated version of the race was then scheduled but stopped when parents of the three stepped in. They said no engagement would take place. The three soon admitted that the “love race” was a hoax and that they did it as a publicity stunt to put Bangor on the map.

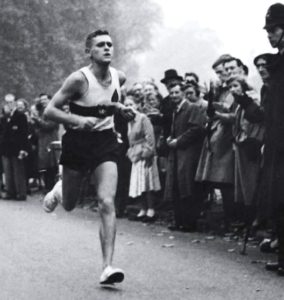

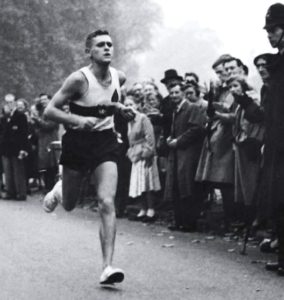

100 miles on a bet

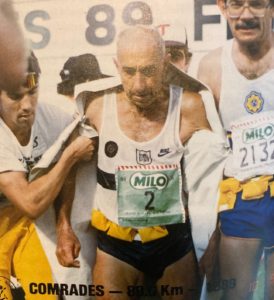

Jackie Mekler of South Africa

Jack “Jackie Mekler” (1932-2019) was yet another amazing ultrarunner from South Africa who also was a five-time winner of the Comrades Marathon. His first Comrades attempt was in 1952. In 1953 he ran in Hayward’s Box to London 100 miler at the ripe age of 21. Mekler finished second to Hayward (12:20:28) with a time of 13:08:06, which also beat the old world record. In 1954 he broke the 50-mile world record with 5:24:27.

In 1958, Mekler decided to try to beat Hayward’s road 100-mile world record. Hayward felt that Mekler could do some comfortably. Mekler did not want to do it in a solo attempt and asked that a race be organized. A sea-level course was found but due to lack of support and Mekler’s poor condition at the time, the idea was dropped and soon Hopcroft broke the 100-mile record that year.

After winning London to Brighton in 1960 with a course record of 5:25:56, just three weeks later Mekler decided to attempt Hopcroft’s 100-mile record on Bath Road going from Hyde Park Corner to Box. He knew that going after records in England was better than in South Africa because of the lower altitude.

The solo run organized by the Orad Runners’ Club started at 4 a.m. on October 16, 1960. The unconventional reverse direction from London was necessary to avoid heavy London traffic in the late afternoon. Ultrarunning legend, Peter Gavuzzi gave him a pre-race massage and Hopcroft, paced him for the first 10 miles out of London. Mekler said, “I appreciated this sporting, kind and encouraging gesture from the record holder.”

A cold wind blew an icy blast on his exposed legs and it seemed impossible for him to warm up. At 17 miles he was only two minutes behind record pace. “I knew I was not running as freely or as easily as I had hoped.” He had his first drink there, bottled lemon squash with glucose and salt. He went on and hit the marathon mark in 3:04 still just two minutes behind the record pace.

“The wind and weather remained cruel. As the darkness of night gave way to the cold, the first hind of trouble occurred in a pain behind my right knee. I continued to run into a strong and icy headwind and my running lacked ease and confidence.” By mile 40 he realized that his chance of event finishing were slipping away, ten minutes behind Hopcroft’s pace. He reached 50 miles in 6:08:06 with a painful knee and swollen Achilles tendon. At that point he quit in great disappointment. “I felt that I had been cheated as I was still full of pent-up energy and enthusiasm, but once again disaster had struck.”

His Achilles injury was serious and in those days was regarded as untreatable and career ending. But in 1961 a successful surgery was performed and in 1962 he had completely healed and was winning races again. Jackie Mekler never raced 100 miles again but went on to complete an impressive running and died in Cape Town, South Africa on July 1, 2019 at the age of 87.

The parts of this 100-mile series:

- 54: Part 1 (1737-1875) Edward Payson Weston

- 55: Part 2 (1874-1878) Women Pedestrians

- 56: Part 3 (1879-1899) 100 Miles Craze

- 57: Part 4 (1900-1919) 100-Mile Records Fall

- 58: Part 5 (1902-1926) London to Brighton and Back

- 59: Part 6 (1927-1934) Arthur Newton

- 60: Part 7 (1930-1950) 100-Milers During the War

- 61: Part 8 (1950-1960) Wally Hayward and Ron Hopcroft

- 62: Part 9 (1961-1968) First Death Valley 100s

- 63: Part 10 (1968-1968) 1969 Walton-on-Thames 100

- 64: Part 11 (1970-1971) Women run 100-milers

- 65: Part 12 (1971-1973) Ron Bentley and Ted Corbitt

- 66: Part 13 (1974-1975) Gordy Ainsleigh

- 67: Part 14 (1975-1976) Cavin Woodward and Tom Osler

- 68: Part 15 (1975-1976) Andy West

- 69: Part 16 (1976-1977) Max Telford and Alan Jones

- 70: Part 17 (1973-1978) Badwater Roots

- 71: Part 18 (1977) Western States 100

- 72: Part 19 (1977) Don Ritchie World Record

- 73: Part 20 (1978-1979) The Unisphere 100

- 74: Part 21 (1978) Ed Dodd and Don Choi

- 75: Part 22 (1978) Fort Mead 100

- 76: Part 23 (1983) The 24-Hour Two-Man Relay

- 77: Part 24 (1978-1979) Alan Price – Ultrawalker

- 79: Part 25 (1978-1984) Early Hawaii 100-milers

- 81: Part 26 (1978) The 1978 Western States 100

- 87: Part 27 (1979) The Old Dominion 100

Sources:

- M. Jamieson, Wally Hayward, Just Call me Wally

- Jackie Mekler, Running Alone: The autobiography of long-distance runner Jackie Mekler

- John Cameron-Dow, Comrades Marathon – The Ultimate Human Race

- “Ron Hopcoft” Thames Valley Harriers

- Ron Hopcoft 100-mile race report

- The Times (Shreveport, Louisiana), Jun 27, 1950

- Valley Times (North Hollywood, California), Jan 20, 1951

- Statesman Journal (Salem, Oregon), Jun21, Jull 3, Aug 2, 1951, Sep 1, 1952, Jul 12, 1961, Apr 30, 1962

- Greater Oregon (Albany, Oregon), Jul 20, 1951

- Albany Democrat-Herald (Albany, Oregon), Jul 19, 1951

- Alabama Journal (Montgomery, Alabama), Nov 23, 1951

- The Vancouver News-Herald (Canada), Nov 23, 1953

- The Miami News (Florida), Nov 21, 1953

- The San Francisco Examiner (California), Nov 23, 1951, Nov 22, 1953

- Coventry Evening Telegraph (England), Sept, 26, Oct 24, Nov 21, 1953, Jan 27, 1954, Oct 17, 24 1959

- Shields Daily News (England), Nov 23, 1953

- Aberdeen Evening Express (England), Nov 23, 1953, Oct 15, 1960

- The Daily Chronicle (De Kalb, Illinois), Jan 31, 1955

- The Daily Register (Harrisburg, Illinois), Jan 24, 1955

- Sunday News (Lancaster, Pennsylvania), Feb 20, 1955

- The Morning News (Wilmington, Delaware), Aug 15, 1957

- The Observer (London, England), Jul 7, 1957, Oct 25, 1959

- The Courier-News (Bridgewater, New Jersey), Mar 31, 1958

- The Ottawa Citizen (Canada), Oct 4, 1958

- Hammersmith & Shepherds Bush Gazette (England), Oct 31, 1958

- Rutland Daily Herald (Vermont), Oct 2, 1959

- The Daily Oklahoman (Oklahoma City, Oklahoma), Oct 25, 1959

- The People (England), Oct 25, 1959

- The Hanford Sentinel (California), Feb 19, 1960

- The Monitor (McAllen, Texas), Feb 19, 1960

- Press and Sun Bulletin (Binghamton, New York), Feb 19, 1960

- The Logansport Press (Indiana), Feb 20, 1960

- The Spokesman-Review (Spokane, Washington), Feb 20, 1960

- The Morning News (Wilmington, Delaware), Feb 20, 1960

- The Press Democrat (Santa Rosa, California), Feb 21, 1960

- Great Falls Tribune (Montana), Feb 21, 1960

- Herald and Review (Decatur, Illinois), Sep 24, 1960

- The Decatur Daily Reivew (Illinois), Sep 25, 1960