Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 32:12 — 40.4MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

During the late 1960s, 100-mile races started to make a comeback both in England and in the United States. Walking 100 miles in under 24 hours became popular in Europe and similar events also started to be held in America, featuring a legendary lumberjack walker from Montana.

During the late 1960s, 100-mile races started to make a comeback both in England and in the United States. Walking 100 miles in under 24 hours became popular in Europe and similar events also started to be held in America, featuring a legendary lumberjack walker from Montana.

Racing 100 miles also rose from the ashes. A long-forgotten indoor 24-hour race started up in Los Angeles California where western ultrarunners strived to reach 100 miles on a tiny track, up seven stories, in the busy downtown metropolis.

But the most significant 100-mile race of the decade was held in 1969, at Walton-on-Thames in Surrey, England. The race featured many of the greatest ultrarunners of the world at that time who were interested in trying to run 100 miles. It was a fitting way to finish out the 1960s and news of the event would help spawn many other 100-milers in the 1970s. In America it re-opened the sport to distances longer than 50 miles.

Race-Walking 100 miles

Larry O’Neil – America’s Walking Champion

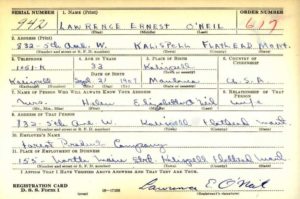

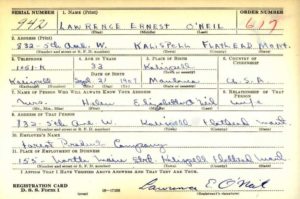

After graduation from college in 1928, with a degree in economics, O’Neil joined his father’s lumber business in Kalispell and then founded the Forest Products Company, a retail lumber yard in Kalispell. He began training to be a marathon runner, hoping to run at Boston in 1932. However, he injured his Achilles tendon at work and that finished his serious running career. But with his arduous outdoor life in Montana, he stayed very physically fit.

In 1964 he attended a National AAU meet held in Kalispell, Montana. It included a 3,000-meter walking race. O’Neil came to watch. He explained, “I looked at the track and field program and saw this 3,000-meter walking event. I didn’t know what it was, but I figured it would be the easiest event of the meet. About that time, there was an announcement over the loudspeaker that two walkers had dropped out.” Walkers were recruited from the stands and O’Neil, age 57, hustled over to enter on a dare. He did well, finishing 4th out of 10 walkers. O’Neil remembered, “I’m sure my form back then might have been declared illegal today. Some judges must have been wearing dark glasses to allow us to finish.” O’Neil discovered that walking long distances were his forte a started seriously competing in 12 AAU events during the next couple years.

America’s National 100-mile Championship

In 1967 O’Neil received word that a National 100-mile walking championship would be held in Columbia Missouri. The event, sponsored by the Columbia Parks and Recreation Department, established by Bill Clark, would be held on the 440-yard Hickman High School Track.

O’Neil said, “I figured they were handing out six trophies so I could probably take sixth. I just wanted to see if I could do it, go 100 miles.” He increased his training. He added sprint running to build up his speed, followed by sprint walking on a track at Flathead High School. He then increased his daily miles on the track to 12 miles. For strength training, he would also walk from the west shore of Flathead Lake to the radar station atop Blacktail Mountain, thirteen miles and a climb of 4,400 feet. “I had to see if the higher altitude bothered my wind. It didn’t”

Then a disappointment occurred. On his last trip up the mountain, he cut the side of his heel. Because of the injury, he was not sure he would be able to compete in the 100-mile event until the day before he was to leave, when he got the okay from his doctor. O’Neil was a bit nervous. “I was cornered. I had been telling my friends I could do better in these walking races if they were a little longer. I had no excuse this time.”

O’Neil, age 60, drove down from Montana and competed against four much younger walkers. Shaul Ladany (1936-) of Israel was the pre-race favorite and got most of the attention. He was undefeated in distances from 50-90 miles and was planning on walking in the 1968 Olympics.

Once in the lead, the attention from spectators turned to him. “High school coaches, college coaches, everyone along the sidelines were yelling that I was going too fast. Not knowing if I was, that was the mental strain. When you’ve got hundreds of laps to go, each lap rolls off awfully slow.”

O’Neil said, “Soon I began to start lapping Ladany and eventually he dropped out of the race at mile 64. It gave me great impetus to see the great Ladany out of the race.” O’Neil only had one extended stop when he needed to tape his feet to protect them from the coarse red shale gravel on the track. He said, “It got in your shoes and felt like there were filings in there. I didn’t want to stop because my muscles stiffen when I do.” He ate only five salt tables, a dozen dextrose tablets, a dozen vitamin C tablets, and lots of water.

During his record walk, O’Neil walked with a very consistent pace throughout and finished with blisters on his feet and was a bit stiff but said he wanted to compete again the next year. He said that the furthest he had previously walked was about 31 miles. “I felt as good as any day in my life and that made the race enjoyable and easy.” A few days later, O’Neil, with sore feet proclaimed, “That was the last one I’m going to be in.”

American Centurions

O’Neil received national attention and it was written, “O’Neil, a modest man with a ready grin, says that while he is in training, he keeps a diet heavy in protein and does a lot of running and walking. Sports Illustrated awarded him a silver bowl for his accomplishment.

O’Neil’s later accomplishments

O’Neil never retired from walking. Later that year he even went to Europe and competed in Sweden. He said, “I would still like to have that one perfect race when I knew I couldn’t do any better. In my last race I didn’t go nearly as fast as my capacity. I wasn’t even tired after 22 hours although my heels were in terrific pain.”

A poem was written in his honor that included:

He gave us pride and determination not to give up the fight.

He gave us words of encouragement that got us through the night.

We’ll never forget the quick, short steps that passed us from behind.

And when asked how he was he’d always say “I doin’ fine”

The Last Day Run – Los Angeles

Why was it held on Halloween, and why was it called “Last Day Run?” The event was called “Last Day” because it was associated with of an annual 30-day “jog” competition that originated in California. This state-wide competition was established in 1964 by the Olympic Club of San Francisco. Runners would run for 30 days in October. The club would award trophies to the running club with the highest total mileage during the month. Seymour decided to create the 1965 “Last Day Run” to help the club competitors pile up miles on the last day of October. In America’s first modern-era 24-hour race, Seymour won with 50 miles.

Lu Dosti

Bud Murphy

Bud Murphy was a 41-year-old advertising executive and long-time amateur athlete. Dosti’s wife wrote that Murphy “was pretty. A strapping 6-foot plus, strawberry-blond, baby-blue-eyed Peter O’Toole.” In contrast she described her husband, Lu, as “a 5-foot-9-inch thinning-down-all-the-time Omar Sharif.” Previously, at the 1967 Last Day Run, Murphy reached 100 miles in less than 24 hours. He was determined to defend his championship and run 100 miles faster in 1968.

1968 Last Day Run

Dosti didn’t sleep at all and developed tendonitis in both feet. At one point he said, “I quit.” But his coach and race director, Steve Seymour, pushed him back on the track. At the same time Murphy had stomach issues and kept throwing up. He also returned to the track “running like a gazelle.”

Three Great Ultrarunners

Late in the 1960s in England, Don Turner had the idea of holding an elite 24-hour hour race but most potential runners desired to run 100 miles. An invitational 100-mile track race was scheduled in 1969 at Walton-on-Thames. Among the entrants were three historically important ultrarunning legends.

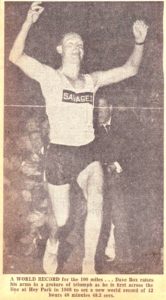

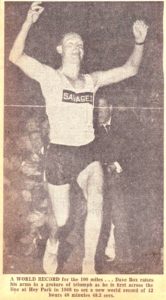

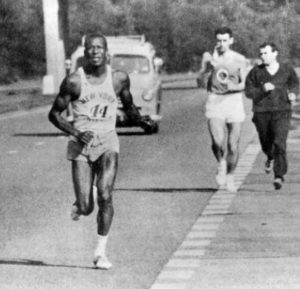

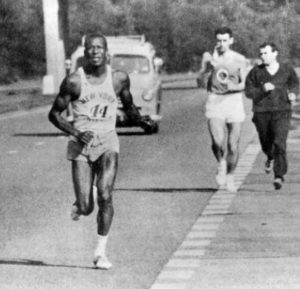

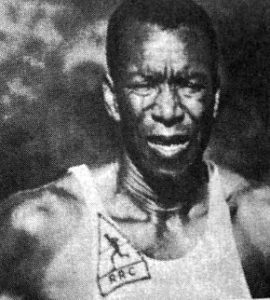

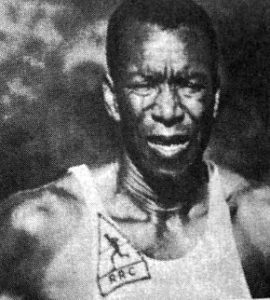

Dave Box

Box had a focused goal of winning the Comrades Marathon (54 miles). To remind him, he put up a plaque in his bedroom that read, “Win the Comrades.” He ran it for the first time in 1965 and placed 41st. His experience and training increased and he finished 7th in 1966 and 5th in 1968.

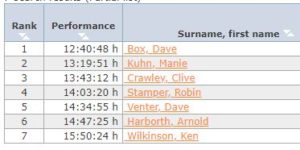

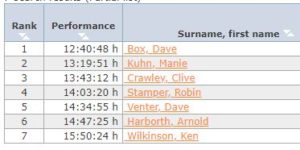

On October 11, 1968, Box went after the 100-mile world record on a track in Durban, South Africa. At least seven runners competed in the Durban 100 Miles Track Race. The race had first been held in 1964 when two runners, Manie Kuhn (1934-2005) and Ray Mover (1930-), tied in 17:48:51. The race was then held every two years until 1992.

In 1968, Box ran extremely well and claimed the world record by six minutes, finishing in 12:40:48. But because of a time recording issue (lap times not recorded), it was not recognized in England. Six runners finished in less than 15 hours, all from South Africa.

Box followed up that terrific performance with a second place finish at 1969 Comrades. He then headed to England in September to compete on the world stage at London to Brighton, where he finished 5th. He then prepared for the historic Walton-on-Thames 100 Mile Track Race.

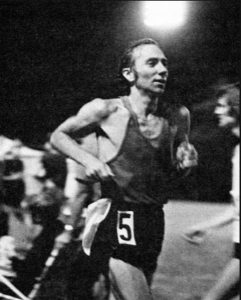

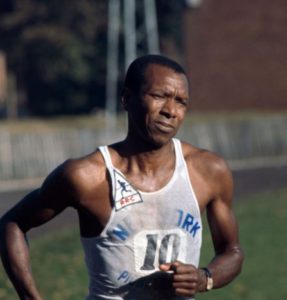

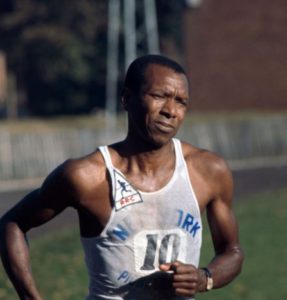

John Tarrant

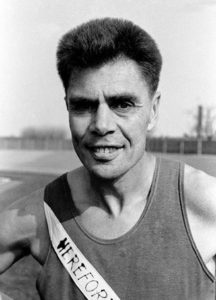

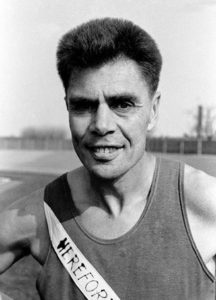

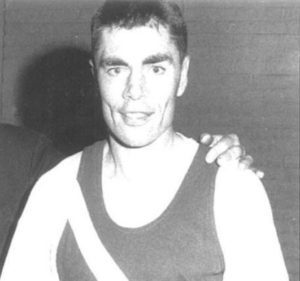

John Tarrant (1932-1975) was born in London, England. In 1950 at the age of 18, he took up boxing and earned 17 pounds at prize-fights at a local town hall. When he discovered that he had talents running, he dreamed of running the marathon in the Olympics and gave up boxing. But he needed to join the Amateur Athletic Association of England (AAA). In 1952 when he tried to register with the organization, he answered honestly that he had a brief career prize-fighting. The AAA officials despised boxing, and unfairly banned him from amateur running competition for life.

But Tarrant wanted to run and compete. He continued to train in the Derbyshire hills, getting faster and stronger. He would frequently run to and from work 12 miles each day. In 1956 at Liverpool, he went unannounced to a 20-mile race with international distance runners. He joined the starters, wearing a shirt without a number, and raced. He dominated, no one could come close to him.

![]()

![]()

But clearly Tarrant had rankled the old running establishment and when he intended to run internationally for Britain, he received a letter from that AAA that stated, “No one who is a reinstated professional may take part in international athletic competition.” Tarrant was greatly disappointed. His Olympic marathon dreams were dashed away and he wrote, “Due to my honesty, I had lost the best athletic years of my life, and now faced the prospect of not realizing my true potential. Society often gave murders a second chance but for seventeen miserable pound notes, I was condemned for life.”

In 1965 he turned his attention to ultrarunning, breaking course records and setting a 40-mile world record in 1966 of 4:03:28 at Cardiff, Wales. In 1967, he became the first man ever to win the grand slam of Britain’s four principal ultramarathons, London to Brighton (52 miles), Isle of Man (39 miles), Exeter-to-Plymouth (44 miles), and Liverpool-to-Blackpool (48 miles).

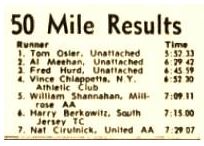

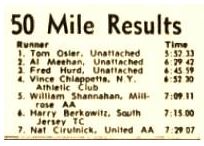

Also in 1967, the first modern-era American 50-mile championship was held as part of the YMCA Thanksgiving Day Road Race, held in Poughkeepsie, New York with 13 starters. Tarrant went to America to compete. But the night before the race, the British AAA cabled the AAU in America demanding that Tarrant be banned from the race. The AAU decided to recognize the ban, even after all his effort and cost to go to the USA to compete.

In 1969, Tarrant went to South Africa to perhaps live permanently. He developed a friendship with rival Dave Box and lived with the Box family. Box said, “We practically adopted him. He had no other social life. No drink. No women. He was part of the family.” Tarrant ran Comrades “bandit” because South African officials unfortunately recognized his international ban. They even warned the other 800 runners not to run near him or they could have action taken against them. Tarrant had a disappointing race with terrible stomach issues and finished in a distant 28th place.

In the fall of 1969 Tarrant decided to return home to England. He set his sights on breaking the 100-mile world record at Walton-on-Thames. No record intrigued him more. He started training about 40-50 miles per day.

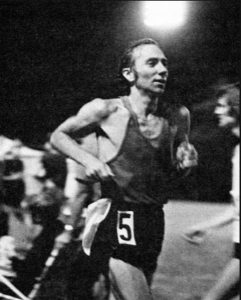

Ted Corbitt

Corbitt was known for the huge miles he would put into training. On four occasions he completed 300-mile training weeks while working full time. He explained, “I was doing a lot of experimenting.”

Tom Osler, America’s 50-mile champion recalled, “My most memorable meeting with Ted came in 1967 or ’68 when my wife Kathy and I visited him in his apartment in the Bronx. We sat in his living room as he described his training for upcoming ultra races. He frequently ran from his apartment to Manhattan, then circled the entire island of Manhattan and returned home, a distance of almost 35 miles. He would carry change with him so that he could ride the subway in case of difficulty. Sometimes he did two laps – nearly 70 miles!”

In 1969, at age 50, Ted was invited compete in the 100-mile race at Walton-on-Thames in England. He trained hard for the race and even did a 100-mile training run to convince himself that he could go that distance.

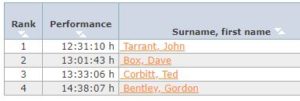

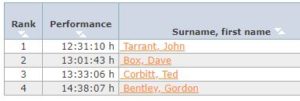

1969 Walton-on-Thames 100 Mile Track Race

The RRC invitational race was organized at Walton-on-Thames in England to make an attempt to break the recognized 100-mile world record that stood at 12:46:34, held by Wally Hayward. The three titans of ultrarunning at that time were invited and traveled to England. They were Dave Box of South Africa, John Tarrant of England (living in South Africa), and Ted Corbitt of New York City. Of the three, only Box had ever raced 100 miles before. The month before the 100-miler, the three had competed against each other at London to Brighton. Corbitt came in 2nd, Box in 5th, and Tarrant DNFed at about 30 miles. Arthur Mail of England also entered the 100-miler. He had run 100 miles in 13:17:59 in 1959.

Runners prepare

During the few week leading up to the historic race, Box joined Tarrant at his Hereford apartment and they trained together. Box recalled, “One day I tripped on a curb and tore my thigh muscles. John took me to the football masseur in Hereford and she was an absolute butcher, and I said it was making it worse not better, so I took a few days off.”

With twelve days to go, Corbitt returned to London. “Once there, the reality of the 100 brought back all the depression and negativism. He became so homesick for his family that he was seriously tempted to take the next plane home.” But he stuck with it and ran a 45 miles park-hoping training run.

Corbitt dreamed the night before that he had broken his leg. A doctor told him to not run for a year. Ted felt relieved that he would not have to run 100 miles. But when he woke up, the leg was fine and there was no way out. He took a train to stay the day before at Don Turner’s home. He slept for several hours and read to pass the time. Neither man talked about the race. Turner didn’t want to jink Corbitt.

As the day of the race approached, Tarrant did not show his usual jitters, but instead exhibited intense calm. He felt confident that he would do well. His extended family travelled down from Buxton to be there to support him. His brother Victor, who always crewed him, was be at his side. Tarrant spent most of the day before the midnight start sleeping and then took a train with his wife to the venue.

Pre-race

There were 25 timekeepers involved to support the 16 starters who would run on a dismal Stompond Lane track at Walton-on-Thames. A special tent was raised in the infield filled with the timers. Sixty officials outnumbered the runners four to one.

“Washing down thick jam sandwiches with honey-sweetened tea, Tarrant still harbored no doubts. As the floodlights sprang on around the 400 meters of cinder, every one of his fellow athletes could sense the change in him.” He showed determination and certainty. One observed said, “You had that feeling he was more organized than usual. He had a lot more people surrounding him, and he seemed to have a premonition that he would win.”

Tarrant arrived about 10 p.m. Corbitt soon also arrived and in the dressing room felt the tension and thought the runners all looked frightened. Ireland’s Noel Henry said, “I’ve look forward to this race for two years and now I don’t want to run it.” Corbitt saw Box and Tarrant restlessly awaiting the gun and realized he would be satisfied to finish and break Sidney Hatch’s American record of 16:07:43 set in 1909 at Riverview Park in Chicago.

Corbitt described, “They used portable lights during the night. They had a tent on the infield which was lit very well. Outside the ten there were blackboards listing 5-mile times.”

The start

“The sky was clouded. The moon struggled through. The gun rang out. They were off on their fantasy journey. Gordon Bentley of Tipton Harriers moved directly into the lead unchallenged with a sub-seven-minute mile pace. The rest quickly broke up into several bunches.”

Tarrant’s plan was to run each lap at 1:45 regardless of what was happening around him. But after a few miles, he increased his speed and tried to gain on Bentley. Box, running with Corbitt, shouted as Tarrant lapped them the second time, saying, “You’ll be sorry later, John.” Bentley increased his lead. Other runners started dropping out as early as 15 miles.

Bentley passed 20 miles in 2:16:26. But by 50k he slowly faded and Tarrant took the lead by mile 40. Box panicked seeing Tarrant go and he tried to catch the Ghost. As Box tried to unlap himself the pace went wild. Corbitt recalled, “The intermittent sprint duel was unbelievable. Box determined to pass and Tarrant was determined not to permit it. And with all those miles left!”

Then without warning, Tarrant stopped and “puked his guts out” for at least a half minute. He thought he was done but soon got back into the race. The struggle between the two friends calmed down as Box, perhaps unwisely, let Tarrant recover. Corbitt watched it all and just ran steady.

For fuel, Tarrant had been drinking a honey and tea mixture with glucose. He ate candy bars, sandwiches, biscuits and drank a half a cup of water every few laps. But after his puking episode, he stayed with orange juice and glucose. Corbitt fueled on apricot nectar, Tiger’s Milk, and a form of energy bar. Box stuffed his mouth with food and drink every lap and was very talkative with other runners.

The miles ticked off and four other runners dropped out by 35 miles. Tarrant stretched his lead to two minutes as Box kept putting on occasional charges. At mile 50, Box finally took the lead for the first time with a time of 5:58:11. Tarrant was struggling and looked beaten. Corbitt reach 50 miles in 6:13:22 feeling good, hoping that Tarrant and Box would annihilate each other. Others dropped out and only nine continued. Box soon had a four-lap lead and Tarrant felt that his chances for victory were gone. He just couldn’t increase his pace, even with his son shouting loudly at him.

It was reported, “Approaching mile 60, the sun rose into a beautiful morning, dispelling the discouragement of the night and bring out fans to cheer the survivors.” The daylight put energy in Tarrant as he found his speed again and started gaining on Box. Tarrant’s brother, Victor, shouted, “If you keep this up you can break the UK record.” Tarrant’s reply was, “Bugger that, I want the world record.”

By mile 70, Tarrant had nearly caught up to Box. “Box could hear the labored breathing of Tarrant behind. Suddenly, the two men were no longer in a marathon, they were in a sprint.” Box surged forward, desperate to hold off Tarrant’s charge. He said, “I hated being overtaken. I couldn’t stand it.” Tarrant’s crew screamed at him to slow down. The two exchanged the lead back and forth. “For lap after lap, the gap between them opened and closed as each tried to outsprint and crush the other.” The only two others left on the track were Corbitt and Bentley.

“This was no longer a sport or something that could be stopped. This was a life-and-death fight for survival. Each man’s battle to finish depended on whether he could control his mind to keep fighting. It was an agonizing, monotonous slog.” Corbitt struggled with terrible painful thigh chafing until an official’s wife found him some petroleum jelly. He said, “The mental part came in somewhere after 11 hours when I realized that every one left in the race could finish if they could control their minds. I would slow up and start drinking. The dispensers were urging me not to stop completely, figuring I might cramp up. This was a possibility, I guess.

The Finish

“With just a few laps to go, the crowd began to chatter and swell. Few of them had slept and until now it had been a cold and boring night. Abandoned flasks and plastic beakers littered the trackside. Every one of the runners who’d staggered out of the race had stayed behind to see what would happen. Without exception, they were bellowing and clapping Tarrant towards victory.”

With five miles to go, Corbitt wasn’t sure he would make it. The laps seemed to be so long. He thought, “I’ve got to finish before something happens. I must keep going.” He came in at 13:33:06, a new American record, crushing the old mark by three and a half hours. At the finish Corbitt was offered beer and sandwiches. He replied that what he really needed was a new pair of legs.

The race “killed” Corbitt a little. He thought his running days were finished. It took him four months to find enthusiasm for a long training run. Box was so sore that the day after he had to walk upstairs backwards. Eight hours after the finish, Tarrant was on a plane bound for South Africa to go back to his dock worker job and his quest to win Comrades. He had obtained a 300 pound loan from his employer to make the trip. He explained, “I won’t finish paying for it until March 1971. If you are keen enough to do something you will always find a way. I have committed myself up to the hilt for the next year and half, but it was worth it.”

The parts of this 100-mile series:

- 54: Part 1 (1737-1875) Edward Payson Weston

- 55: Part 2 (1874-1878) Women Pedestrians

- 56: Part 3 (1879-1899) 100 Miles Craze

- 57: Part 4 (1900-1919) 100-Mile Records Fall

- 58: Part 5 (1902-1926) London to Brighton and Back

- 59: Part 6 (1927-1934) Arthur Newton

- 60: Part 7 (1930-1950) 100-Milers During the War

- 61: Part 8 (1950-1960) Wally Hayward and Ron Hopcroft

- 62: Part 9 (1961-1968) First Death Valley 100s

- 63: Part 10 (1968-1968) 1969 Walton-on-Thames 100

- 64: Part 11 (1970-1971) Women run 100-milers

- 65: Part 12 (1971-1973) Ron Bentley and Ted Corbitt

- 66: Part 13 (1974-1975) Gordy Ainsleigh

- 67: Part 14 (1975-1976) Cavin Woodward and Tom Osler

- 68: Part 15 (1975-1976) Andy West

- 69: Part 16 (1976-1977) Max Telford and Alan Jones

- 70: Part 17 (1973-1978) Badwater Roots

- 71: Part 18 (1977) Western States 100

- 72: Part 19 (1977) Don Ritchie World Record

- 73: Part 20 (1978-1979) The Unisphere 100

- 74: Part 21 (1978) Ed Dodd and Don Choi

- 75: Part 22 (1978) Fort Mead 100

- 76: Part 23 (1983) The 24-Hour Two-Man Relay

- 77: Part 24 (1978-1979) Alan Price – Ultrawalker

- 79: Part 25 (1978-1984) Early Hawaii 100-milers

- 81: Part 26 (1978) The 1978 Western States 100

- 87: Part 27 (1979) The Old Dominion 100

Sources

- United States Centurion Walkers

- Bill Jones, The Ghost Runner: The Epic Journey of the Man They Couldn’t Stop

- John Chodes, Corbitt: The Story of Ted Corbitt, Long Distance Runner

- The Independent Record (Helena, Montana), Oct 19, 1977

- The Daily Inter Lake (Kalispell, Montana), Sep 25, 28, Oct 30, 1967

- Great Falls Tribune (Montana), Sep 25, Oct 8, 1967

- Chicago Tribune (Illinois), Sep 25, 1967

- Daily Independent Journal (San Rafael, California), Dec 16, 1968

- Coventry Evening Telegraph (England), Oct 12, 1968

- Los Angeles Times (California), Nov 7, 1968

- Los Angeles Times West Magazine, Jan 10, 1971

- Sports Argus (England), May 10, 1958

- Coventry Evening Telegraph, May 15, 1958

- The People (England), Jun 8, 1958

- Birmingham Daily Post (England), Oct 27, 1969

- The Sacramento Bee (California), Oct 17, 1970